User login

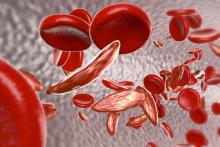

BETHESDA, MD – While there are experimental treatments such as sevuparin and gene therapy in testing for sickle cell disease (SCD), researchers said this field is lagging because of a lack of funding.

Yogen Saunthararajah, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, described what he called a “paltry” landscape of new drugs for SCD at Sickle Cell in Focus, a conference held by the National Institutes of Health.

There are only four main approaches taken by drugs now in clinical testing for addressing the root causes of SCD, despite decades’ worth of research of the genetic and mechanistic underpinnings of this disease, he said.

“It’s pretty sad,” Dr. Saunthararajah said, referring to the quantity of efforts, not their quality.

Within days of his presentation at the conference, one of the drugs he highlighted had officially fallen out of contention. An Oct. 26 post on NIH’s Clinicaltrials.gov site said Incyte had terminated its phase 1 study of INCB059872 in SCD “due to a business decision” not to pursue this indication. Incyte confirmed that it dropped development of INCB059872 for SCD but will continue testing it for other indications, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Dr. Saunthararajah said that work on another approach, using decitabine (Dacogen), for which he has done a phase 1 study, is “struggling,” because of the search for funding.

Two other approaches that Dr. Saunthararajah cited in his presentation appear to remain on track. These are gene therapy and the once-daily voxelotor treatment from Global Blood Therapeutics.

In the field of gene therapy, Sangamo Therapeutics and Sanofi’s Bioverativ in May said the Food and Drug Administration had cleared the way for them to start a phase 1/2 clinical trial for the BIVV003 product that they are developing together. This uses zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) gene-editing technology to modifying a short sequence of the BCL11A gene, with the aim of reactivating fetal hemoglobin.

Bluebird Bio’s LentiGlobin gene therapy has advanced as far as phase 3 for transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia and phase 1/2 for SCD. In October, the European Medicines Agency accepted the company’s application for approval of LentiGlobin gene therapy for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-beta0/beta0 genotype. The company has not said when it expects to file with the FDA for approval of this treatment.

In the field of oral therapies, Global Blood Therapeutics has said it’s in discussions with the FDA about a potential accelerated approval of voxelotor. The tablet is meant to inhibit the underlying mechanism that causes sickling of red blood cells. In June, the company completed a planned review of early data from its phase 3 trial, known as the HOPE study.

“On the primary endpoint (the proportion of patients with greater than 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin versus baseline), a statistically significant increase was demonstrated with voxelotor at both the 1,500-mg and 900-mg doses after 12 weeks of treatment versus placebo,” Global Blood Therapeutics said in an August regulatory filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The company has said that voxelotor may meet the FDA’s standard for accelerated approval under Subpart H program.

In his presentation at the NIH conference, Tom Williams, MD, PhD, of KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme highlighted a recent review of experimental SCD treatments by Marilyn Jo Telen, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C. (Blood. 2016;127[7]:810-9).

Also among the drugs being tested for SCD is Modus Therapeutics’ sevuparin, which Dr. Williams described as being “a heparin-like molecule without the anticoagulant complications.”

The compound originated as a “passion project” of Mats Wahlgren, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who developed it for the treatment of malaria, Dr. Williams said. The company that’s developing sevuparin, Modus Therapeutics, is moving it forward first as a treatment for SCD for commercial reasons, Dr. Williams said.

“They think it’s a better first target,” he said.

An ongoing study of sevuparin for painful crisis is expected to be completed in December, with data then expected to be released in the middle of 2019, Ellen K. Donnelly, PhD, chief executive officer of Modus Therapeutics, said in an interview. She cited a mix of scientific, medical and commercial reasons for her company’s decision to advance sevuparin in SCD.

“First, and most importantly, there is proof of clinical benefit of a similar molecule (the low-molecular-weight heparin called tinzaparin) in patients with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Donnelly said. “Unfortunately, there is a bleeding risk with tinzaparin that limits use of the agent for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Sevuparin does not have the bleeding risk and thus is a strong candidate for SCD.”

Dr. Donnelly also noted the emphasis that the FDA’s Division of Hematology Products has put on development of therapeutics for SCD as a reason for proceeding first with this indication. The agency and the American Society of Hematology in early October held a workshop of experts, physicians, patients, and industry collaborators focused on identifying new endpoints for clinical studies.

Still, she noted that commercial reasons did factor into this decision.

“[I]t is possible for a small company like Modus to take an asset all the way to market when developing a therapeutic for a rare disease given the need for fewer patients and smaller trials,” Dr. Donnelly wrote. “As you can see from www.clinicaltrials.gov, we were able to run our phase 2 study with a small number of sites. In addition, in SCD it is possible to get approval with only one or two confirmatory studies.”

Financial interests

Other drugs in testing for SCD include rivipansel from GlycoMimetics, for which Pfizer is leading development. The sponsors expect to complete the so-called RESET trial by 2019, according to the clinicaltrials.gov. In this study, which is intended to enroll 350 participants, patients who have vaso-occlusive crises are randomly selected for treatment with either rivipansel or placebo.

Speaking during a question-and-answer session at the NIH conference, Robert Swift, PhD, said there’s a need for inexpensive oral drugs to treat SCD. Many other options will remain beyond the finances of people living in poor countries, he said.

“We need to focus not only on the root cause, but on something that is oral and inexpensive to solve the greater sickle cell problem,” Dr. Swift said.

Large drugmakers already have hospital-based sales forces, making SCD drugs administered in this setting attractive to them, he said.

“This is partly about where money is. The drug companies are going where the money is. It’s not oral drugs to treat everybody, it’s something else,” Dr. Swift said. “So someone else is going to have to fund the basic research” into treatments that could be more broadly used.

Dr. Swift said in an interview that he has received NIH funding for developing SCD-101, an oral drug, for which a placebo-controlled crossover study is underway.

Presenters at the NIH conference, including Dr. Saunthararajah, expressed frustration about what they see as relatively little work being done on SCD despite decades of knowledge about the root causes. Like Dr. Swift, he criticized the approach taken in selecting which treatments advance in this field.

“It’s not being driven by what is the most cost effective, what the patients need the most,” Dr. Saunthararajah said. “It’s driven by what will make the most money, not just for [the] drug company, but also for the hospital and also for the physicians.”

Dr. Saunthararajah reported having patents and patent applications around decitabine/tetrahydrouridine, 5-azacytidine/tetrahydrouridine, and differentiation therapy for oncology. He has also been a consultant for EpiDestiny, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda Oncology. Dr. Williams reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Swift is a managing member of Invenux and reported equity in Mast Therapeutics and SCD Development.

This article was updated on 11/9/2018.

BETHESDA, MD – While there are experimental treatments such as sevuparin and gene therapy in testing for sickle cell disease (SCD), researchers said this field is lagging because of a lack of funding.

Yogen Saunthararajah, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, described what he called a “paltry” landscape of new drugs for SCD at Sickle Cell in Focus, a conference held by the National Institutes of Health.

There are only four main approaches taken by drugs now in clinical testing for addressing the root causes of SCD, despite decades’ worth of research of the genetic and mechanistic underpinnings of this disease, he said.

“It’s pretty sad,” Dr. Saunthararajah said, referring to the quantity of efforts, not their quality.

Within days of his presentation at the conference, one of the drugs he highlighted had officially fallen out of contention. An Oct. 26 post on NIH’s Clinicaltrials.gov site said Incyte had terminated its phase 1 study of INCB059872 in SCD “due to a business decision” not to pursue this indication. Incyte confirmed that it dropped development of INCB059872 for SCD but will continue testing it for other indications, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Dr. Saunthararajah said that work on another approach, using decitabine (Dacogen), for which he has done a phase 1 study, is “struggling,” because of the search for funding.

Two other approaches that Dr. Saunthararajah cited in his presentation appear to remain on track. These are gene therapy and the once-daily voxelotor treatment from Global Blood Therapeutics.

In the field of gene therapy, Sangamo Therapeutics and Sanofi’s Bioverativ in May said the Food and Drug Administration had cleared the way for them to start a phase 1/2 clinical trial for the BIVV003 product that they are developing together. This uses zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) gene-editing technology to modifying a short sequence of the BCL11A gene, with the aim of reactivating fetal hemoglobin.

Bluebird Bio’s LentiGlobin gene therapy has advanced as far as phase 3 for transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia and phase 1/2 for SCD. In October, the European Medicines Agency accepted the company’s application for approval of LentiGlobin gene therapy for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-beta0/beta0 genotype. The company has not said when it expects to file with the FDA for approval of this treatment.

In the field of oral therapies, Global Blood Therapeutics has said it’s in discussions with the FDA about a potential accelerated approval of voxelotor. The tablet is meant to inhibit the underlying mechanism that causes sickling of red blood cells. In June, the company completed a planned review of early data from its phase 3 trial, known as the HOPE study.

“On the primary endpoint (the proportion of patients with greater than 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin versus baseline), a statistically significant increase was demonstrated with voxelotor at both the 1,500-mg and 900-mg doses after 12 weeks of treatment versus placebo,” Global Blood Therapeutics said in an August regulatory filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The company has said that voxelotor may meet the FDA’s standard for accelerated approval under Subpart H program.

In his presentation at the NIH conference, Tom Williams, MD, PhD, of KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme highlighted a recent review of experimental SCD treatments by Marilyn Jo Telen, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C. (Blood. 2016;127[7]:810-9).

Also among the drugs being tested for SCD is Modus Therapeutics’ sevuparin, which Dr. Williams described as being “a heparin-like molecule without the anticoagulant complications.”

The compound originated as a “passion project” of Mats Wahlgren, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who developed it for the treatment of malaria, Dr. Williams said. The company that’s developing sevuparin, Modus Therapeutics, is moving it forward first as a treatment for SCD for commercial reasons, Dr. Williams said.

“They think it’s a better first target,” he said.

An ongoing study of sevuparin for painful crisis is expected to be completed in December, with data then expected to be released in the middle of 2019, Ellen K. Donnelly, PhD, chief executive officer of Modus Therapeutics, said in an interview. She cited a mix of scientific, medical and commercial reasons for her company’s decision to advance sevuparin in SCD.

“First, and most importantly, there is proof of clinical benefit of a similar molecule (the low-molecular-weight heparin called tinzaparin) in patients with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Donnelly said. “Unfortunately, there is a bleeding risk with tinzaparin that limits use of the agent for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Sevuparin does not have the bleeding risk and thus is a strong candidate for SCD.”

Dr. Donnelly also noted the emphasis that the FDA’s Division of Hematology Products has put on development of therapeutics for SCD as a reason for proceeding first with this indication. The agency and the American Society of Hematology in early October held a workshop of experts, physicians, patients, and industry collaborators focused on identifying new endpoints for clinical studies.

Still, she noted that commercial reasons did factor into this decision.

“[I]t is possible for a small company like Modus to take an asset all the way to market when developing a therapeutic for a rare disease given the need for fewer patients and smaller trials,” Dr. Donnelly wrote. “As you can see from www.clinicaltrials.gov, we were able to run our phase 2 study with a small number of sites. In addition, in SCD it is possible to get approval with only one or two confirmatory studies.”

Financial interests

Other drugs in testing for SCD include rivipansel from GlycoMimetics, for which Pfizer is leading development. The sponsors expect to complete the so-called RESET trial by 2019, according to the clinicaltrials.gov. In this study, which is intended to enroll 350 participants, patients who have vaso-occlusive crises are randomly selected for treatment with either rivipansel or placebo.

Speaking during a question-and-answer session at the NIH conference, Robert Swift, PhD, said there’s a need for inexpensive oral drugs to treat SCD. Many other options will remain beyond the finances of people living in poor countries, he said.

“We need to focus not only on the root cause, but on something that is oral and inexpensive to solve the greater sickle cell problem,” Dr. Swift said.

Large drugmakers already have hospital-based sales forces, making SCD drugs administered in this setting attractive to them, he said.

“This is partly about where money is. The drug companies are going where the money is. It’s not oral drugs to treat everybody, it’s something else,” Dr. Swift said. “So someone else is going to have to fund the basic research” into treatments that could be more broadly used.

Dr. Swift said in an interview that he has received NIH funding for developing SCD-101, an oral drug, for which a placebo-controlled crossover study is underway.

Presenters at the NIH conference, including Dr. Saunthararajah, expressed frustration about what they see as relatively little work being done on SCD despite decades of knowledge about the root causes. Like Dr. Swift, he criticized the approach taken in selecting which treatments advance in this field.

“It’s not being driven by what is the most cost effective, what the patients need the most,” Dr. Saunthararajah said. “It’s driven by what will make the most money, not just for [the] drug company, but also for the hospital and also for the physicians.”

Dr. Saunthararajah reported having patents and patent applications around decitabine/tetrahydrouridine, 5-azacytidine/tetrahydrouridine, and differentiation therapy for oncology. He has also been a consultant for EpiDestiny, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda Oncology. Dr. Williams reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Swift is a managing member of Invenux and reported equity in Mast Therapeutics and SCD Development.

This article was updated on 11/9/2018.

BETHESDA, MD – While there are experimental treatments such as sevuparin and gene therapy in testing for sickle cell disease (SCD), researchers said this field is lagging because of a lack of funding.

Yogen Saunthararajah, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, described what he called a “paltry” landscape of new drugs for SCD at Sickle Cell in Focus, a conference held by the National Institutes of Health.

There are only four main approaches taken by drugs now in clinical testing for addressing the root causes of SCD, despite decades’ worth of research of the genetic and mechanistic underpinnings of this disease, he said.

“It’s pretty sad,” Dr. Saunthararajah said, referring to the quantity of efforts, not their quality.

Within days of his presentation at the conference, one of the drugs he highlighted had officially fallen out of contention. An Oct. 26 post on NIH’s Clinicaltrials.gov site said Incyte had terminated its phase 1 study of INCB059872 in SCD “due to a business decision” not to pursue this indication. Incyte confirmed that it dropped development of INCB059872 for SCD but will continue testing it for other indications, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Dr. Saunthararajah said that work on another approach, using decitabine (Dacogen), for which he has done a phase 1 study, is “struggling,” because of the search for funding.

Two other approaches that Dr. Saunthararajah cited in his presentation appear to remain on track. These are gene therapy and the once-daily voxelotor treatment from Global Blood Therapeutics.

In the field of gene therapy, Sangamo Therapeutics and Sanofi’s Bioverativ in May said the Food and Drug Administration had cleared the way for them to start a phase 1/2 clinical trial for the BIVV003 product that they are developing together. This uses zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) gene-editing technology to modifying a short sequence of the BCL11A gene, with the aim of reactivating fetal hemoglobin.

Bluebird Bio’s LentiGlobin gene therapy has advanced as far as phase 3 for transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia and phase 1/2 for SCD. In October, the European Medicines Agency accepted the company’s application for approval of LentiGlobin gene therapy for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-beta0/beta0 genotype. The company has not said when it expects to file with the FDA for approval of this treatment.

In the field of oral therapies, Global Blood Therapeutics has said it’s in discussions with the FDA about a potential accelerated approval of voxelotor. The tablet is meant to inhibit the underlying mechanism that causes sickling of red blood cells. In June, the company completed a planned review of early data from its phase 3 trial, known as the HOPE study.

“On the primary endpoint (the proportion of patients with greater than 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin versus baseline), a statistically significant increase was demonstrated with voxelotor at both the 1,500-mg and 900-mg doses after 12 weeks of treatment versus placebo,” Global Blood Therapeutics said in an August regulatory filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The company has said that voxelotor may meet the FDA’s standard for accelerated approval under Subpart H program.

In his presentation at the NIH conference, Tom Williams, MD, PhD, of KEMRI/Wellcome Trust Research Programme highlighted a recent review of experimental SCD treatments by Marilyn Jo Telen, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C. (Blood. 2016;127[7]:810-9).

Also among the drugs being tested for SCD is Modus Therapeutics’ sevuparin, which Dr. Williams described as being “a heparin-like molecule without the anticoagulant complications.”

The compound originated as a “passion project” of Mats Wahlgren, MD, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who developed it for the treatment of malaria, Dr. Williams said. The company that’s developing sevuparin, Modus Therapeutics, is moving it forward first as a treatment for SCD for commercial reasons, Dr. Williams said.

“They think it’s a better first target,” he said.

An ongoing study of sevuparin for painful crisis is expected to be completed in December, with data then expected to be released in the middle of 2019, Ellen K. Donnelly, PhD, chief executive officer of Modus Therapeutics, said in an interview. She cited a mix of scientific, medical and commercial reasons for her company’s decision to advance sevuparin in SCD.

“First, and most importantly, there is proof of clinical benefit of a similar molecule (the low-molecular-weight heparin called tinzaparin) in patients with sickle cell disease,” Dr. Donnelly said. “Unfortunately, there is a bleeding risk with tinzaparin that limits use of the agent for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Sevuparin does not have the bleeding risk and thus is a strong candidate for SCD.”

Dr. Donnelly also noted the emphasis that the FDA’s Division of Hematology Products has put on development of therapeutics for SCD as a reason for proceeding first with this indication. The agency and the American Society of Hematology in early October held a workshop of experts, physicians, patients, and industry collaborators focused on identifying new endpoints for clinical studies.

Still, she noted that commercial reasons did factor into this decision.

“[I]t is possible for a small company like Modus to take an asset all the way to market when developing a therapeutic for a rare disease given the need for fewer patients and smaller trials,” Dr. Donnelly wrote. “As you can see from www.clinicaltrials.gov, we were able to run our phase 2 study with a small number of sites. In addition, in SCD it is possible to get approval with only one or two confirmatory studies.”

Financial interests

Other drugs in testing for SCD include rivipansel from GlycoMimetics, for which Pfizer is leading development. The sponsors expect to complete the so-called RESET trial by 2019, according to the clinicaltrials.gov. In this study, which is intended to enroll 350 participants, patients who have vaso-occlusive crises are randomly selected for treatment with either rivipansel or placebo.

Speaking during a question-and-answer session at the NIH conference, Robert Swift, PhD, said there’s a need for inexpensive oral drugs to treat SCD. Many other options will remain beyond the finances of people living in poor countries, he said.

“We need to focus not only on the root cause, but on something that is oral and inexpensive to solve the greater sickle cell problem,” Dr. Swift said.

Large drugmakers already have hospital-based sales forces, making SCD drugs administered in this setting attractive to them, he said.

“This is partly about where money is. The drug companies are going where the money is. It’s not oral drugs to treat everybody, it’s something else,” Dr. Swift said. “So someone else is going to have to fund the basic research” into treatments that could be more broadly used.

Dr. Swift said in an interview that he has received NIH funding for developing SCD-101, an oral drug, for which a placebo-controlled crossover study is underway.

Presenters at the NIH conference, including Dr. Saunthararajah, expressed frustration about what they see as relatively little work being done on SCD despite decades of knowledge about the root causes. Like Dr. Swift, he criticized the approach taken in selecting which treatments advance in this field.

“It’s not being driven by what is the most cost effective, what the patients need the most,” Dr. Saunthararajah said. “It’s driven by what will make the most money, not just for [the] drug company, but also for the hospital and also for the physicians.”

Dr. Saunthararajah reported having patents and patent applications around decitabine/tetrahydrouridine, 5-azacytidine/tetrahydrouridine, and differentiation therapy for oncology. He has also been a consultant for EpiDestiny, Novo Nordisk, and Takeda Oncology. Dr. Williams reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Swift is a managing member of Invenux and reported equity in Mast Therapeutics and SCD Development.

This article was updated on 11/9/2018.

REPORTING FROM SICKLE CELL IN FOCUS