User login

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

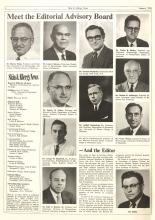

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.