User login

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

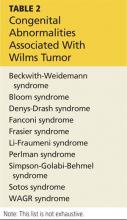

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.

Q) In school, they always emphasized the abdominal exam to rule out Wilms tumors. Are Wilms tumors still with us? Has treatment and evaluation changed?

Wilms tumor is a renal cancer found most commonly in children younger than 9 and represents approximately 7% of all malignancies in children.8,9 It can occur in one or both kidneys, with earlier diagnosis noted with bilateral involvement. Risk is highest among non-Hispanic white persons and African-Americans and lowest among Asians.8

Wilms tumor develops due to a genetic mutation in the WT1 gene located on the 11p13 chromosome. Defects are also noted on the 11p15 chromosome and the p53 tumor suppressor gene.10 Urbach et al recently identified a relationship between the LIN28 gene and Wilms tumor.11 Tumors develop when embryonic renal cells that should cease growing at the time of birth continue to grow in the postnatal period. Wilms tumor can be familial or sporadic. It can also be associated with various congenital anomalies manifested within various syndromes (see Table 2), as well as isolated genitourinary abnormalities, especially in boys.10

Most children present with a palpable, smooth, firm, generally painless mass in the abdomen; those who have bilateral renal involvement usually present earlier than those with unilateral involvement. Palpation of the abdomen during examination, if vigorous, can result in rupture of the renal capsule and tumor spillage. Additional symptoms include hematuria, fever, and hypertension. Referral to pediatric oncology is imperative.12

Definitive diagnosis is made by histologic evaluation following biopsy or surgical excision.13 Other possible diagnostic tests include but are not limited to abdominal ultrasound or CT; chest CT (to rule out metastatic lung disease); urinalysis (to evaluate for hematuria and proteinuria); liver function studies (to evaluate for hepatic involvement); and laboratory studies to measure coagulation, serum calcium, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and complete blood count.

Histologic examination for staging (I-V) occurs following surgical excision of the tumor. There are two staging systems available: the National Wilms Tumor Study, based on postoperative tumor evaluation, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology, based on postchemotherapy evaluation.13

Treatment options include surgical excision (including complete nephrectomy of the affected kidney), chemotherapy based on tumor staging, and internal and/or external radiation therapy.13

Susan E. Brown, MS, ARNP,

ACNP-BC, CCRN

Great River Nephrology,

West Burlington, Iowa

REFERENCES

1. United States Renal Data System. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States (2012). www.usrds.org/2012/view/v1_01.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

2. Kopp JB, Nelson GW, Sampath K, et al. APOL1 genetic variants in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy.

J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(11):2129-2137.

3. Parsa A, Kao L, Xie D, et al; AASK and CRIC Study Investigators. APOL1 risk variants, race and progression of chronic kidney disease.

N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183-2196.

4. Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(9):1484-1491.

5. Lipkowitz MS, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, et al; AASK Investigators. Apolipoprotein L1 gene variants associate with hypertension-attributed nephropathy and the rate of kidney function decline in African Americans. Kidney Int. 2013;83(1):114–120.

6. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(5):1025-1030.

7. Partners Healthcare Personalized Medicine. Order APOL1 genotyping test for non-diabetic nephropathy kidney disease. http://personal izedmedicine.partners.org/Laboratory-For-Molecular-Medicine/Ordering/Kidney-Dis ease/APOL1-Gene-Sequencing.aspx. Accessed October 19, 2014.

8. Grovas A, Fremgen A, Rauck A, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on patterns of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer. 1997;80(12):2321-2332.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wilm’s tumor. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/kimmel_cancer_center/centers/pediatric_oncology/cancer_types/wilms_tumor.html. Accessed October 19, 2014.

10. Dome JS, Huff V. Wilms tumor overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al (eds). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2014. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1294/. Accessed October 19, 2014.

11. Urbach A, Yermalovich A, Zhang J, et al. Lin28 sustains early renal progenitors and induces Wilms tumor. Genes & Dev. 2014;28:971-982.

12. Fernandez C, Geller JI, Ehrlich PF, et al. Renal tumors. In: Pizzo P, Poplack D (eds). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. 6th ed, St Louis, MO: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011; 861.

13. Metzger ML, Dome JS. Current therapy for Wilms’ tumor. Oncologist. 2005;10(10):815-826.