User login

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

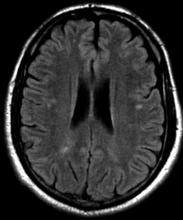

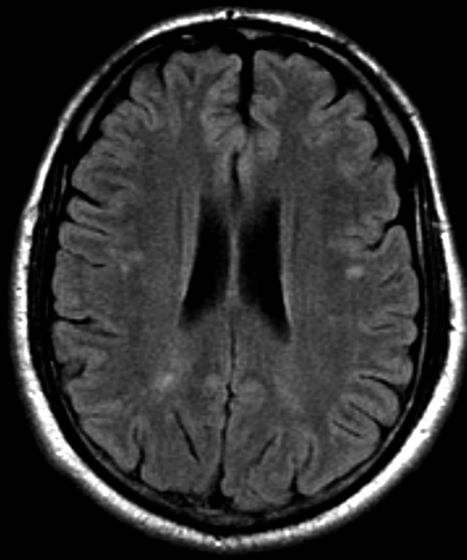

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 16-year-old female patient presents with a severe ipsilateral headache. She describes that before the onset of head pain, she felt like she could not control her facial muscles on one side, and she was unable to speak in full sentences. She reports that these symptoms probably lasted an hour or so, and she was worried that she was experiencing an allergic reaction, though she reports no known allergies. In terms of family history, the patient explains that she does not have a close relationship with her father, but she recalls that he experienced similar episodes. She notes a history of frequent and recurrent headaches, varying in severity, for which she usually takes a high dose of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).