User login

Case: 'He's okay on weekends'

Nathan, age 13, is referred by his parents for recent school refusal behavior. He has had difficulty adjusting to middle school and has been marked absent one-third of school days this academic year. These absences come in the form of tardiness, skipped classes, and full-day absences.

Nathan complains of headaches and stomachaches and says he feels upset and nervous while in school. His parents, however, complain that Nathan seems fine on weekends and holidays and seems to be embellishing symptoms to miss school. Nathan’s parents are concerned that their son may have some physical or mental condition that is preventing his school attendance and that might be remediated with medication.

Child-motivated refusal to attend school or remain in class an entire day is not uncommon, affecting 5% to 28% of youths at some time in their lives.1,2

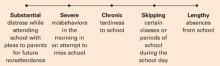

The behavior may be viewed along a spectrum of absenteeism (Figure), and a child may exhibit all forms of absenteeism at one time or another. In Nathan’s case, for example, he could be anxious during school on Monday, arrive late to school on Tuesday, skip afternoon classes on Wednesday, and fail to attend school completely on Thursday and Friday.

In this article you will learn characteristics of school refusal behavior to watch for and assess, and treatment strategies for youths ages 5 to 17. You will also find advice and techniques to offer parents.

Figure A child might exhibit each behavior on this spectrum at different times

Refusal behavior characteristics

School refusal behavior encompasses all subsets of problematic absenteeism, such as truancy, school phobia, and separation anxiety.3 Children and adolescents of all ages, boys and girls alike, can exhibit school refusal behavior. The most common age of onset is 10 to 13 years. Youths such as Nathan who are entering a school building for the first time—especially elementary and middle school—are at particular risk for school refusal behavior. Little information is available regarding ethnic differences, although school dropout rates for Hispanics are often considerably elevated compared with other ethnic groups.4,5

School refusal behavior covers a range of symptoms, diagnoses, somatic complaints, and medical conditions (Tables 1-3).6-12 Longitudinal studies indicate that school refusal behavior, if left unaddressed, can lead to serious short-term problems, such as distress, academic decline, alienation from peers, family conflict, and financial and legal consequences. Common long-term problems include school dropout, delinquent behaviors, economic deprivation, social isolation, marital problems, and difficulty maintaining employment. Approximately 52% of adolescents with school refusal behavior meet criteria for an anxiety, depressive, conduct-personality, or other psychiatric disorder later in life.13-16

Table 1

Common symptoms that could signal school refusal behavior

| Internalizing/covert symptoms | Externalizing/overt symptoms |

|---|---|

| Depression | Aggression |

| Fatigue/tiredness | Clinging to an adult |

| Fear and panic | Excessive reassurance-seeking behavior |

| General and social anxiety | Noncompliance and defiance |

| Self-consciousness | Refusal to move in the morning |

| Somatization | Running away from school or home |

| Worry | Temper tantrums and crying |

Table 2

Primary psychiatric disorders among youths with school refusal behavior

| Diagnosis | Percentage |

|---|---|

| None | 32.9% |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 22.4% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 10.5% |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 8.4% |

| Major depression | 4.9% |

| Specific phobia | 4.2% |

| Social anxiety disorder | 3.5% |

| Conduct disorder | 2.8% |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1.4% |

| Panic disorder | 1.4% |

| Enuresis | 0.7% |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.7% |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

Table 3

Somatic complaints and medical conditions

commonly associated with school refusal behavior

| Somatic complaints | Medical conditions |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea/irritable bowel | Allergic rhinitis |

| Fatigue | Asthma and respiratory illness |

| Headache and stomachache | Chronic pain and illness (notably cancer, Crohn’s disease, dyspepsia, hemophilia, chronic fatigue syndrome) |

| Nausea and vomiting | Diabetes |

| Palpitations and perspiration | Dysmenorrhea |

| Recurrent abdominal pain or other pain | Head louse infestation |

| Shaking or trembling | Influenza |

| Sleep problems | Orodental disease |

Finding a reason for school refusal

If a child has somatic complaints, you can expect to find that the child is:

- suffering from a true physical malady

- embellishing low-grade physical symptoms from stress or attention-seeking behavior

- reporting physical problems that have no medical basis.

A full medical examination is always recommended to rule out organic problems or to properly treat true medical conditions.

Four functions. If no medical condition is found, explore the reasons a particular child refuses school. A common model of conceptualizing school refusal behavior involves reinforcers:1,2

- to avoid school-based stimuli that provoke a sense of negative affectivity, or combined anxiety and depression; examples of key stimuli include teachers, peers, bus, cafeteria, classroom, and transitions between classes

- to escape aversive social or evaluative situations such as conversing or otherwise interacting with others or performing before others as in class presentations

- to pursue attention from significant others, such as wanting to stay home or go to work with parents

- to pursue tangible reinforcers outside of school, such as sleeping late, watching television, playing with friends, or engaging in delinquent behavior or substance use.

The first 2 functions are maintained by negative reinforcement or a desire to leave anxiety-provoking stimuli. The latter 2 functions are maintained by positive reinforcement, or a desire to pursue rewards outside of school. Youths may also refuse school for a combination of these reasons.17 In Nathan’s case, he was initially anxious about school in general (the first function). After his parents allowed him to stay home for a few days, however, he was refusing school to enjoy fun activities such as video games at home (the last function).

Violence on school campuses across the country naturally makes many parents skittish about possible copycat incidents. In fact, some parents acquiesce to their children’s pleas to remain home on school shooting anniversaries—particularly the Columbine tragedy of April 20, 1999.

Student and parental fears likely are exacerbated by new episodes of violence, such as three school shootings in 2006:

- On September 27, a 53-year-old man entered a high school in Bailey, Colorado, and shot one girl before killing himself.

- On September 29, a high school student near Madison, Wisconsin, killed his principal after being disciplined for carrying tobacco.

- On October 2, a heavily armed man barricaded himself in a one-room Amish schoolhouse in Paradise, Pennsylvania. He bound and shot 11 girls before killing himself, and five of the girls died.

Compared with highly publicized school violence, however, personal victimization is a much stronger factor in absenteeism.32 Specifically, school violence is related to school absenteeism especially for youths who have been previously victimized. The literature shows:

- Students who have been bullied are 2.1 times more likely than other students to feel unsafe at school.

- 20% of elementary school children report they would skip school to avoid being bullied.33

- High school students’ fear of attending classes because of violence is directly associated with victimization by teachers or other students.

- Missing school because of feeling unsafe is a strong risk factor for asthma and, potentially, being sent home early from school.34

Assessment scale. One method for quickly assessing the role of these functions is the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised.18,19 This scale poses 24 questions, the answers to which measure the relative strength of each of the 4 functions. Versions are available for children and parents, who complete their respective scales separately (see Related resources). Item means are calculated across the measures to help determine the primary reason for a child’s school refusal.

In addition to using the assessment scale, you may ask interview questions regarding the form and function of school refusal behavior (Tables 4,5). Take care to assess attendance history and patterns, comorbid conditions, instances of legitimate absenteeism, family disruption, and a child’s social and academic status. Specific questions about function can help narrow the reason for school refusal.

Assess specific school-related stimuli that provoke absenteeism such as social and evaluative situations, whether a child could attend school with a parent (evidence of attention-seeking), and what tangible rewards a child receives for absenteeism throughout the school day. Information about the form and function of school refusal behavior may also be evident during in-office observations of the family. Data from the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised, interviews, and observations can then be used to recommend particular treatment options.

Table 4

Questions related to forms of school refusal behavior

| What are the child’s specific forms of absenteeism, and how do these forms change daily? | What specific school-related stimuli are provoking the child’s concern about going to school? |

| Is a child’s school refusal behavior relatively acute or chronic in nature (in related fashion, how did the child’s school refusal behavior develop over time)? | Is the child’s refusal to attend school legitimate or understandable in some way (eg, school-based threat, bullying, inadequate school climate)? |

| What comorbid conditions occur with a child’s school refusal behavior (Table 3), including substance abuse? | What family disruption or conflict has occurred as a result of a child’s school refusal behavior? |

| What is the child’s degree of anxiety or misbehavior upon entering school, and what specific misbehaviors are present in the morning before school (Table 2)? | What is the child’s academic and social status? (This should include a review of academic records, formal evaluation reports, attendance records, and individualized education plans or 504 plans as applicable.) |

Table 5

Questions related to functions of school refusal behavior

| Have recent or traumatic home or school events influenced a child’s school refusal behavior? | Is the child willing to attend school if a parent accompanies him or her? |

| Are symptoms of school refusal behavior evident on weekends and holidays? | What specific tangible rewards does the child pursue outside of school that cause him or her to miss school? |

| Are there any nonschool situations where anxiety or attention-seeking behavior occurs? | Is the child willing to attend school if incentives are provided for attendance? |

| What specific social and/or evaluative situations at school are avoided? |

Treating youths who refuse school

Treatment success will be better assured if you work closely with school personnel and parents to gather and share information, coordinate a plan for returning a child to school, and address familial issues and the child’s comorbid medical problems that impact attendance.

Medications have proven useful in alleviating severe cases of anxiety and depression, and cognitive management techniques can be applied to the child, the parents, and the family together.

Anxiolytics or antidepressants. Pharmacotherapy research for school refusal behavior is in its infancy. Some investigators have found, however, that a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) such as imipramine, 3 mg/kg/d, may be useful in some cases20,21—generally for youths ages 10 to 17 years with better attendance records and fewer symptoms of social avoidance and separation anxiety.22 Researchers speculate that TCAs, which are not always effective in children, may influence symptoms such as anhedonia or sleep problems that contribute to school refusal behavior.

With respect to substantial child anxiety and depression without school refusal behavior, researchers have focused on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In particular, fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d, fluvoxamine, 50 to 250 mg/d, sertraline, 85 to 160 mg/d, and paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d, have been useful for youths with symptoms of general and social anxiety and depression.23,24

Youths often do not respond to these medications as well as adults do, however, because of the fluid and amorphous nature of anxious and depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents. Careful monitoring is required when treating youth with SSRIs, which have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior.

Psychological techniques. Sophisticated clinical controlled studies have addressed the treatment of diverse youths with school refusal behavior.25-28 Options for this population may be arranged according to function or the primary reinforcers maintaining absenteeism:

- child-based techniques to manage anxiety in a school setting

- parent-based techniques to manage contingencies for school attendance and nonattendance

- family-based techniques to manage incentives and disincentives for school attendance and nonattendance.

Child-based anxiety management techniques include relaxation training, breathing retraining, cognitive therapy (generally for youths ages 9 to 17), and exposure-based practices to gradually reintroduce a child to school. These techniques have been strongly supported by randomized controlled trials specific to school refusal behavior2 and are useful for treating general anxiety and depression as well.

Parent-based contingency management techniques include establishing morning and evening routines, modifying parental commands toward brevity and clarity, providing attention-based consequences for school nonattendance (such as early bedtime, limited time with a parent at night), reducing excessive child questioning or reassurance-seeking behavior, and engaging in forced school attendance under strict conditions. Parent-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general29 but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Family-based techniques include developing written contracts to increase incentives for school attendance and decrease incentives for nonattendance, escorting a child to school and classes, and teaching youths to refuse offers from peers to miss school.30 As with parent-based techniques, family-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general, but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Gradual reintroduction to school

A preferred approach to resolve school refusal behavior usually involves gradual reintegration to school and classes. This may include initial attendance at lunchtime, 1 or 2 favorite classes, or in an alternative classroom setting such as a guidance counselor’s office or school library. Gradual reintegration into regular classrooms may then proceed.

If possible, a child should remain in school during the day and not be sent home unless intense medical symptoms are present.30 A recommended list of intense symptoms includes:

- frequent vomiting

- bleeding

- temperature >100° F

- severe diarrhea

- lice

- acute flu-like symptoms

- extreme medical conditions such as intense pain.

Case continued: a full-time student.

A structured diagnostic interview and other behavioral assessment measures show that Nathan meets criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. He worries excessively about his social and academic performance at school and displays several somatic complaints related to anxiety. His treatment thus involves a two-pronged approach:

- sertraline, 50 mg/d, which has been found to significantly reduce symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in youths ages 5 to 17.

- child-based anxiety management techniques and family therapy to increase incentives for school attendance and limit fun activities during a school day spent at home.

His therapist and family physician collaborate with school personnel to gradually reintroduce Nathan to a full-time academic schedule.

- Copies of the child and parent versions of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised are available at www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=4322&UID=.

- King NJ, Bernstein GA. School refusal in children and adolescents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:197-205.

- Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

- Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. Parent workbook/therapist’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Acknowledgment

Adapted and reprinted with permission from The Journal of Family Practice, August 2006, p 685-92.

1. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychol: Sci Prac 1996;3:339-54.

2. Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. Hansen C, Sanders SL, Massaro S, Last CG. Predictors of severity of absenteeism in children with anxiety-based school refusal. J Clin Child Psychol 1998;27:246-54.

4. Franklin CG, Soto I. Keeping Hispanic youths in school. Children & Schools 2002;24:139-43.

5. Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:797-807.

6. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry 2001;35:822-6.

7. Kearney CA, Albano AM. The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: diagnostic aspects. Behav Modif 2004;28:147-61.

8. Bernstein GA, Massie ED, Thuras PD, Perwien AR, Borchardt CM, Crosby RD. Somatic symptoms in anxious-depressed school refusers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:661-8.

9. Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and absenteeism related to respiratory illness in school children. Am J Epidemiology 2003;157:861-9.

10. Glaab LA, Brown R, Daneman D. School attendance in children with type I diabetes. Diabetic Med 2005;22:421-6.

11. Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterology 2004;99:2442-51.

12. Buitelaar JK, van Andel H, Duyx JHM, van Strien DC. Depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescence: a follow-up study of adolescents with school refusal. Acta Paedopsychiatrica 1994;56:249-53.

13. Flakierska-Praquin N, Lindstrom M, Gillberg C. School phobia with separation anxiety disorder: a comparative 20- to 29-year follow-up study of 35 school refusers. Comp Psychiatry 1997;38:17-22.

14. Hibbett A, Fogelman K. Future lives of truants: family formation and health-related behaviour. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:171-9.

15. Hibbett A, Fogelman K, Manor O. Occupational outcomes of truancy. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:23-36.

16. Kearney CA. Bridging the gap among professionals who address youth with school absenteeism: overview and suggestions for consensus. Prof Psychol Res Prac 2003;34:57-65.

17. King NJ, Heyne D, Tonge B, Gullone E, Ollendick TH. School refusal: categorical diagnoses, functional analysis and treatment planning. Clin Psychol Psychother 2001;8:352-60.

18. Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the School Refusal Assessment Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2002;24:235-45.

19. Kearney CA. Confirmatory factor analysis of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised: child and parent versions. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2006; in press.

20. Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM, Perwein AR, et al. Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2000;39:276-83.

21. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. A critical review of pharmacotherapy for youth with anxiety disorders: things are not as they seem. J Anxiety Disord 1998;12:83-102.

22. Layne AE, Bernstein GA, Egan EA, Kushner MG. Predictors of treatment response in anxious-depressed adolescents with school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2003;42:319-26.

23. Compton SN, Grant PJ, Chrisman AK, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: an open trial. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:564-71.

24. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-5.

25. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. Functionally-based prescriptive and nonprescriptive treatment for children and adolescents with school refusal behavior. Behav Ther 1999;30:673-95.

26. King NJ, Tonge BJ, Heyne D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school-refusing children: A controlled evaluation. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:395-403.

27. Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school phobia. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:404-11.

28. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-20.

29. Kearney CA, Roblek TL. Parent training in the treatment of school refusal behavior. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, eds. Handbook of parent training: parents as co-therapists for children’s behavior problems, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1998:225-56.

30. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach/Therapist’s guide. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 2000.

31. Kearney CA, Bates M. Addressing school refusal behavior: Suggestions for frontline professionals. Children & Schools 2005;27:207-16.

32. Astor RA, Benbenishty R, Zeira A, Vinokur A. School climate, observed risky behaviors, and victimization as predictors of high school students’ fear and judgments of school violence as a problem. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:716-36.

33. Glew GM, Fan M-Y, Katon W, Rivara FP, Kernic MA. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:1026-31.

34. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. The associations between victimization, feeling unsafe, and asthma episodes among US high-school students. Am J Public Health 2006;96:802-4.

Case: 'He's okay on weekends'

Nathan, age 13, is referred by his parents for recent school refusal behavior. He has had difficulty adjusting to middle school and has been marked absent one-third of school days this academic year. These absences come in the form of tardiness, skipped classes, and full-day absences.

Nathan complains of headaches and stomachaches and says he feels upset and nervous while in school. His parents, however, complain that Nathan seems fine on weekends and holidays and seems to be embellishing symptoms to miss school. Nathan’s parents are concerned that their son may have some physical or mental condition that is preventing his school attendance and that might be remediated with medication.

Child-motivated refusal to attend school or remain in class an entire day is not uncommon, affecting 5% to 28% of youths at some time in their lives.1,2

The behavior may be viewed along a spectrum of absenteeism (Figure), and a child may exhibit all forms of absenteeism at one time or another. In Nathan’s case, for example, he could be anxious during school on Monday, arrive late to school on Tuesday, skip afternoon classes on Wednesday, and fail to attend school completely on Thursday and Friday.

In this article you will learn characteristics of school refusal behavior to watch for and assess, and treatment strategies for youths ages 5 to 17. You will also find advice and techniques to offer parents.

Figure A child might exhibit each behavior on this spectrum at different times

Refusal behavior characteristics

School refusal behavior encompasses all subsets of problematic absenteeism, such as truancy, school phobia, and separation anxiety.3 Children and adolescents of all ages, boys and girls alike, can exhibit school refusal behavior. The most common age of onset is 10 to 13 years. Youths such as Nathan who are entering a school building for the first time—especially elementary and middle school—are at particular risk for school refusal behavior. Little information is available regarding ethnic differences, although school dropout rates for Hispanics are often considerably elevated compared with other ethnic groups.4,5

School refusal behavior covers a range of symptoms, diagnoses, somatic complaints, and medical conditions (Tables 1-3).6-12 Longitudinal studies indicate that school refusal behavior, if left unaddressed, can lead to serious short-term problems, such as distress, academic decline, alienation from peers, family conflict, and financial and legal consequences. Common long-term problems include school dropout, delinquent behaviors, economic deprivation, social isolation, marital problems, and difficulty maintaining employment. Approximately 52% of adolescents with school refusal behavior meet criteria for an anxiety, depressive, conduct-personality, or other psychiatric disorder later in life.13-16

Table 1

Common symptoms that could signal school refusal behavior

| Internalizing/covert symptoms | Externalizing/overt symptoms |

|---|---|

| Depression | Aggression |

| Fatigue/tiredness | Clinging to an adult |

| Fear and panic | Excessive reassurance-seeking behavior |

| General and social anxiety | Noncompliance and defiance |

| Self-consciousness | Refusal to move in the morning |

| Somatization | Running away from school or home |

| Worry | Temper tantrums and crying |

Table 2

Primary psychiatric disorders among youths with school refusal behavior

| Diagnosis | Percentage |

|---|---|

| None | 32.9% |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 22.4% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 10.5% |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 8.4% |

| Major depression | 4.9% |

| Specific phobia | 4.2% |

| Social anxiety disorder | 3.5% |

| Conduct disorder | 2.8% |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1.4% |

| Panic disorder | 1.4% |

| Enuresis | 0.7% |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.7% |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

Table 3

Somatic complaints and medical conditions

commonly associated with school refusal behavior

| Somatic complaints | Medical conditions |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea/irritable bowel | Allergic rhinitis |

| Fatigue | Asthma and respiratory illness |

| Headache and stomachache | Chronic pain and illness (notably cancer, Crohn’s disease, dyspepsia, hemophilia, chronic fatigue syndrome) |

| Nausea and vomiting | Diabetes |

| Palpitations and perspiration | Dysmenorrhea |

| Recurrent abdominal pain or other pain | Head louse infestation |

| Shaking or trembling | Influenza |

| Sleep problems | Orodental disease |

Finding a reason for school refusal

If a child has somatic complaints, you can expect to find that the child is:

- suffering from a true physical malady

- embellishing low-grade physical symptoms from stress or attention-seeking behavior

- reporting physical problems that have no medical basis.

A full medical examination is always recommended to rule out organic problems or to properly treat true medical conditions.

Four functions. If no medical condition is found, explore the reasons a particular child refuses school. A common model of conceptualizing school refusal behavior involves reinforcers:1,2

- to avoid school-based stimuli that provoke a sense of negative affectivity, or combined anxiety and depression; examples of key stimuli include teachers, peers, bus, cafeteria, classroom, and transitions between classes

- to escape aversive social or evaluative situations such as conversing or otherwise interacting with others or performing before others as in class presentations

- to pursue attention from significant others, such as wanting to stay home or go to work with parents

- to pursue tangible reinforcers outside of school, such as sleeping late, watching television, playing with friends, or engaging in delinquent behavior or substance use.

The first 2 functions are maintained by negative reinforcement or a desire to leave anxiety-provoking stimuli. The latter 2 functions are maintained by positive reinforcement, or a desire to pursue rewards outside of school. Youths may also refuse school for a combination of these reasons.17 In Nathan’s case, he was initially anxious about school in general (the first function). After his parents allowed him to stay home for a few days, however, he was refusing school to enjoy fun activities such as video games at home (the last function).

Violence on school campuses across the country naturally makes many parents skittish about possible copycat incidents. In fact, some parents acquiesce to their children’s pleas to remain home on school shooting anniversaries—particularly the Columbine tragedy of April 20, 1999.

Student and parental fears likely are exacerbated by new episodes of violence, such as three school shootings in 2006:

- On September 27, a 53-year-old man entered a high school in Bailey, Colorado, and shot one girl before killing himself.

- On September 29, a high school student near Madison, Wisconsin, killed his principal after being disciplined for carrying tobacco.

- On October 2, a heavily armed man barricaded himself in a one-room Amish schoolhouse in Paradise, Pennsylvania. He bound and shot 11 girls before killing himself, and five of the girls died.

Compared with highly publicized school violence, however, personal victimization is a much stronger factor in absenteeism.32 Specifically, school violence is related to school absenteeism especially for youths who have been previously victimized. The literature shows:

- Students who have been bullied are 2.1 times more likely than other students to feel unsafe at school.

- 20% of elementary school children report they would skip school to avoid being bullied.33

- High school students’ fear of attending classes because of violence is directly associated with victimization by teachers or other students.

- Missing school because of feeling unsafe is a strong risk factor for asthma and, potentially, being sent home early from school.34

Assessment scale. One method for quickly assessing the role of these functions is the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised.18,19 This scale poses 24 questions, the answers to which measure the relative strength of each of the 4 functions. Versions are available for children and parents, who complete their respective scales separately (see Related resources). Item means are calculated across the measures to help determine the primary reason for a child’s school refusal.

In addition to using the assessment scale, you may ask interview questions regarding the form and function of school refusal behavior (Tables 4,5). Take care to assess attendance history and patterns, comorbid conditions, instances of legitimate absenteeism, family disruption, and a child’s social and academic status. Specific questions about function can help narrow the reason for school refusal.

Assess specific school-related stimuli that provoke absenteeism such as social and evaluative situations, whether a child could attend school with a parent (evidence of attention-seeking), and what tangible rewards a child receives for absenteeism throughout the school day. Information about the form and function of school refusal behavior may also be evident during in-office observations of the family. Data from the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised, interviews, and observations can then be used to recommend particular treatment options.

Table 4

Questions related to forms of school refusal behavior

| What are the child’s specific forms of absenteeism, and how do these forms change daily? | What specific school-related stimuli are provoking the child’s concern about going to school? |

| Is a child’s school refusal behavior relatively acute or chronic in nature (in related fashion, how did the child’s school refusal behavior develop over time)? | Is the child’s refusal to attend school legitimate or understandable in some way (eg, school-based threat, bullying, inadequate school climate)? |

| What comorbid conditions occur with a child’s school refusal behavior (Table 3), including substance abuse? | What family disruption or conflict has occurred as a result of a child’s school refusal behavior? |

| What is the child’s degree of anxiety or misbehavior upon entering school, and what specific misbehaviors are present in the morning before school (Table 2)? | What is the child’s academic and social status? (This should include a review of academic records, formal evaluation reports, attendance records, and individualized education plans or 504 plans as applicable.) |

Table 5

Questions related to functions of school refusal behavior

| Have recent or traumatic home or school events influenced a child’s school refusal behavior? | Is the child willing to attend school if a parent accompanies him or her? |

| Are symptoms of school refusal behavior evident on weekends and holidays? | What specific tangible rewards does the child pursue outside of school that cause him or her to miss school? |

| Are there any nonschool situations where anxiety or attention-seeking behavior occurs? | Is the child willing to attend school if incentives are provided for attendance? |

| What specific social and/or evaluative situations at school are avoided? |

Treating youths who refuse school

Treatment success will be better assured if you work closely with school personnel and parents to gather and share information, coordinate a plan for returning a child to school, and address familial issues and the child’s comorbid medical problems that impact attendance.

Medications have proven useful in alleviating severe cases of anxiety and depression, and cognitive management techniques can be applied to the child, the parents, and the family together.

Anxiolytics or antidepressants. Pharmacotherapy research for school refusal behavior is in its infancy. Some investigators have found, however, that a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) such as imipramine, 3 mg/kg/d, may be useful in some cases20,21—generally for youths ages 10 to 17 years with better attendance records and fewer symptoms of social avoidance and separation anxiety.22 Researchers speculate that TCAs, which are not always effective in children, may influence symptoms such as anhedonia or sleep problems that contribute to school refusal behavior.

With respect to substantial child anxiety and depression without school refusal behavior, researchers have focused on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In particular, fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d, fluvoxamine, 50 to 250 mg/d, sertraline, 85 to 160 mg/d, and paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d, have been useful for youths with symptoms of general and social anxiety and depression.23,24

Youths often do not respond to these medications as well as adults do, however, because of the fluid and amorphous nature of anxious and depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents. Careful monitoring is required when treating youth with SSRIs, which have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior.

Psychological techniques. Sophisticated clinical controlled studies have addressed the treatment of diverse youths with school refusal behavior.25-28 Options for this population may be arranged according to function or the primary reinforcers maintaining absenteeism:

- child-based techniques to manage anxiety in a school setting

- parent-based techniques to manage contingencies for school attendance and nonattendance

- family-based techniques to manage incentives and disincentives for school attendance and nonattendance.

Child-based anxiety management techniques include relaxation training, breathing retraining, cognitive therapy (generally for youths ages 9 to 17), and exposure-based practices to gradually reintroduce a child to school. These techniques have been strongly supported by randomized controlled trials specific to school refusal behavior2 and are useful for treating general anxiety and depression as well.

Parent-based contingency management techniques include establishing morning and evening routines, modifying parental commands toward brevity and clarity, providing attention-based consequences for school nonattendance (such as early bedtime, limited time with a parent at night), reducing excessive child questioning or reassurance-seeking behavior, and engaging in forced school attendance under strict conditions. Parent-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general29 but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Family-based techniques include developing written contracts to increase incentives for school attendance and decrease incentives for nonattendance, escorting a child to school and classes, and teaching youths to refuse offers from peers to miss school.30 As with parent-based techniques, family-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general, but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Gradual reintroduction to school

A preferred approach to resolve school refusal behavior usually involves gradual reintegration to school and classes. This may include initial attendance at lunchtime, 1 or 2 favorite classes, or in an alternative classroom setting such as a guidance counselor’s office or school library. Gradual reintegration into regular classrooms may then proceed.

If possible, a child should remain in school during the day and not be sent home unless intense medical symptoms are present.30 A recommended list of intense symptoms includes:

- frequent vomiting

- bleeding

- temperature >100° F

- severe diarrhea

- lice

- acute flu-like symptoms

- extreme medical conditions such as intense pain.

Case continued: a full-time student.

A structured diagnostic interview and other behavioral assessment measures show that Nathan meets criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. He worries excessively about his social and academic performance at school and displays several somatic complaints related to anxiety. His treatment thus involves a two-pronged approach:

- sertraline, 50 mg/d, which has been found to significantly reduce symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in youths ages 5 to 17.

- child-based anxiety management techniques and family therapy to increase incentives for school attendance and limit fun activities during a school day spent at home.

His therapist and family physician collaborate with school personnel to gradually reintroduce Nathan to a full-time academic schedule.

- Copies of the child and parent versions of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised are available at www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=4322&UID=.

- King NJ, Bernstein GA. School refusal in children and adolescents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:197-205.

- Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

- Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. Parent workbook/therapist’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Acknowledgment

Adapted and reprinted with permission from The Journal of Family Practice, August 2006, p 685-92.

Case: 'He's okay on weekends'

Nathan, age 13, is referred by his parents for recent school refusal behavior. He has had difficulty adjusting to middle school and has been marked absent one-third of school days this academic year. These absences come in the form of tardiness, skipped classes, and full-day absences.

Nathan complains of headaches and stomachaches and says he feels upset and nervous while in school. His parents, however, complain that Nathan seems fine on weekends and holidays and seems to be embellishing symptoms to miss school. Nathan’s parents are concerned that their son may have some physical or mental condition that is preventing his school attendance and that might be remediated with medication.

Child-motivated refusal to attend school or remain in class an entire day is not uncommon, affecting 5% to 28% of youths at some time in their lives.1,2

The behavior may be viewed along a spectrum of absenteeism (Figure), and a child may exhibit all forms of absenteeism at one time or another. In Nathan’s case, for example, he could be anxious during school on Monday, arrive late to school on Tuesday, skip afternoon classes on Wednesday, and fail to attend school completely on Thursday and Friday.

In this article you will learn characteristics of school refusal behavior to watch for and assess, and treatment strategies for youths ages 5 to 17. You will also find advice and techniques to offer parents.

Figure A child might exhibit each behavior on this spectrum at different times

Refusal behavior characteristics

School refusal behavior encompasses all subsets of problematic absenteeism, such as truancy, school phobia, and separation anxiety.3 Children and adolescents of all ages, boys and girls alike, can exhibit school refusal behavior. The most common age of onset is 10 to 13 years. Youths such as Nathan who are entering a school building for the first time—especially elementary and middle school—are at particular risk for school refusal behavior. Little information is available regarding ethnic differences, although school dropout rates for Hispanics are often considerably elevated compared with other ethnic groups.4,5

School refusal behavior covers a range of symptoms, diagnoses, somatic complaints, and medical conditions (Tables 1-3).6-12 Longitudinal studies indicate that school refusal behavior, if left unaddressed, can lead to serious short-term problems, such as distress, academic decline, alienation from peers, family conflict, and financial and legal consequences. Common long-term problems include school dropout, delinquent behaviors, economic deprivation, social isolation, marital problems, and difficulty maintaining employment. Approximately 52% of adolescents with school refusal behavior meet criteria for an anxiety, depressive, conduct-personality, or other psychiatric disorder later in life.13-16

Table 1

Common symptoms that could signal school refusal behavior

| Internalizing/covert symptoms | Externalizing/overt symptoms |

|---|---|

| Depression | Aggression |

| Fatigue/tiredness | Clinging to an adult |

| Fear and panic | Excessive reassurance-seeking behavior |

| General and social anxiety | Noncompliance and defiance |

| Self-consciousness | Refusal to move in the morning |

| Somatization | Running away from school or home |

| Worry | Temper tantrums and crying |

Table 2

Primary psychiatric disorders among youths with school refusal behavior

| Diagnosis | Percentage |

|---|---|

| None | 32.9% |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 22.4% |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 10.5% |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 8.4% |

| Major depression | 4.9% |

| Specific phobia | 4.2% |

| Social anxiety disorder | 3.5% |

| Conduct disorder | 2.8% |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 1.4% |

| Panic disorder | 1.4% |

| Enuresis | 0.7% |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.7% |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

Table 3

Somatic complaints and medical conditions

commonly associated with school refusal behavior

| Somatic complaints | Medical conditions |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea/irritable bowel | Allergic rhinitis |

| Fatigue | Asthma and respiratory illness |

| Headache and stomachache | Chronic pain and illness (notably cancer, Crohn’s disease, dyspepsia, hemophilia, chronic fatigue syndrome) |

| Nausea and vomiting | Diabetes |

| Palpitations and perspiration | Dysmenorrhea |

| Recurrent abdominal pain or other pain | Head louse infestation |

| Shaking or trembling | Influenza |

| Sleep problems | Orodental disease |

Finding a reason for school refusal

If a child has somatic complaints, you can expect to find that the child is:

- suffering from a true physical malady

- embellishing low-grade physical symptoms from stress or attention-seeking behavior

- reporting physical problems that have no medical basis.

A full medical examination is always recommended to rule out organic problems or to properly treat true medical conditions.

Four functions. If no medical condition is found, explore the reasons a particular child refuses school. A common model of conceptualizing school refusal behavior involves reinforcers:1,2

- to avoid school-based stimuli that provoke a sense of negative affectivity, or combined anxiety and depression; examples of key stimuli include teachers, peers, bus, cafeteria, classroom, and transitions between classes

- to escape aversive social or evaluative situations such as conversing or otherwise interacting with others or performing before others as in class presentations

- to pursue attention from significant others, such as wanting to stay home or go to work with parents

- to pursue tangible reinforcers outside of school, such as sleeping late, watching television, playing with friends, or engaging in delinquent behavior or substance use.

The first 2 functions are maintained by negative reinforcement or a desire to leave anxiety-provoking stimuli. The latter 2 functions are maintained by positive reinforcement, or a desire to pursue rewards outside of school. Youths may also refuse school for a combination of these reasons.17 In Nathan’s case, he was initially anxious about school in general (the first function). After his parents allowed him to stay home for a few days, however, he was refusing school to enjoy fun activities such as video games at home (the last function).

Violence on school campuses across the country naturally makes many parents skittish about possible copycat incidents. In fact, some parents acquiesce to their children’s pleas to remain home on school shooting anniversaries—particularly the Columbine tragedy of April 20, 1999.

Student and parental fears likely are exacerbated by new episodes of violence, such as three school shootings in 2006:

- On September 27, a 53-year-old man entered a high school in Bailey, Colorado, and shot one girl before killing himself.

- On September 29, a high school student near Madison, Wisconsin, killed his principal after being disciplined for carrying tobacco.

- On October 2, a heavily armed man barricaded himself in a one-room Amish schoolhouse in Paradise, Pennsylvania. He bound and shot 11 girls before killing himself, and five of the girls died.

Compared with highly publicized school violence, however, personal victimization is a much stronger factor in absenteeism.32 Specifically, school violence is related to school absenteeism especially for youths who have been previously victimized. The literature shows:

- Students who have been bullied are 2.1 times more likely than other students to feel unsafe at school.

- 20% of elementary school children report they would skip school to avoid being bullied.33

- High school students’ fear of attending classes because of violence is directly associated with victimization by teachers or other students.

- Missing school because of feeling unsafe is a strong risk factor for asthma and, potentially, being sent home early from school.34

Assessment scale. One method for quickly assessing the role of these functions is the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised.18,19 This scale poses 24 questions, the answers to which measure the relative strength of each of the 4 functions. Versions are available for children and parents, who complete their respective scales separately (see Related resources). Item means are calculated across the measures to help determine the primary reason for a child’s school refusal.

In addition to using the assessment scale, you may ask interview questions regarding the form and function of school refusal behavior (Tables 4,5). Take care to assess attendance history and patterns, comorbid conditions, instances of legitimate absenteeism, family disruption, and a child’s social and academic status. Specific questions about function can help narrow the reason for school refusal.

Assess specific school-related stimuli that provoke absenteeism such as social and evaluative situations, whether a child could attend school with a parent (evidence of attention-seeking), and what tangible rewards a child receives for absenteeism throughout the school day. Information about the form and function of school refusal behavior may also be evident during in-office observations of the family. Data from the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised, interviews, and observations can then be used to recommend particular treatment options.

Table 4

Questions related to forms of school refusal behavior

| What are the child’s specific forms of absenteeism, and how do these forms change daily? | What specific school-related stimuli are provoking the child’s concern about going to school? |

| Is a child’s school refusal behavior relatively acute or chronic in nature (in related fashion, how did the child’s school refusal behavior develop over time)? | Is the child’s refusal to attend school legitimate or understandable in some way (eg, school-based threat, bullying, inadequate school climate)? |

| What comorbid conditions occur with a child’s school refusal behavior (Table 3), including substance abuse? | What family disruption or conflict has occurred as a result of a child’s school refusal behavior? |

| What is the child’s degree of anxiety or misbehavior upon entering school, and what specific misbehaviors are present in the morning before school (Table 2)? | What is the child’s academic and social status? (This should include a review of academic records, formal evaluation reports, attendance records, and individualized education plans or 504 plans as applicable.) |

Table 5

Questions related to functions of school refusal behavior

| Have recent or traumatic home or school events influenced a child’s school refusal behavior? | Is the child willing to attend school if a parent accompanies him or her? |

| Are symptoms of school refusal behavior evident on weekends and holidays? | What specific tangible rewards does the child pursue outside of school that cause him or her to miss school? |

| Are there any nonschool situations where anxiety or attention-seeking behavior occurs? | Is the child willing to attend school if incentives are provided for attendance? |

| What specific social and/or evaluative situations at school are avoided? |

Treating youths who refuse school

Treatment success will be better assured if you work closely with school personnel and parents to gather and share information, coordinate a plan for returning a child to school, and address familial issues and the child’s comorbid medical problems that impact attendance.

Medications have proven useful in alleviating severe cases of anxiety and depression, and cognitive management techniques can be applied to the child, the parents, and the family together.

Anxiolytics or antidepressants. Pharmacotherapy research for school refusal behavior is in its infancy. Some investigators have found, however, that a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) such as imipramine, 3 mg/kg/d, may be useful in some cases20,21—generally for youths ages 10 to 17 years with better attendance records and fewer symptoms of social avoidance and separation anxiety.22 Researchers speculate that TCAs, which are not always effective in children, may influence symptoms such as anhedonia or sleep problems that contribute to school refusal behavior.

With respect to substantial child anxiety and depression without school refusal behavior, researchers have focused on selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). In particular, fluoxetine, 10 to 20 mg/d, fluvoxamine, 50 to 250 mg/d, sertraline, 85 to 160 mg/d, and paroxetine, 10 to 50 mg/d, have been useful for youths with symptoms of general and social anxiety and depression.23,24

Youths often do not respond to these medications as well as adults do, however, because of the fluid and amorphous nature of anxious and depressive symptomatology in children and adolescents. Careful monitoring is required when treating youth with SSRIs, which have been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior.

Psychological techniques. Sophisticated clinical controlled studies have addressed the treatment of diverse youths with school refusal behavior.25-28 Options for this population may be arranged according to function or the primary reinforcers maintaining absenteeism:

- child-based techniques to manage anxiety in a school setting

- parent-based techniques to manage contingencies for school attendance and nonattendance

- family-based techniques to manage incentives and disincentives for school attendance and nonattendance.

Child-based anxiety management techniques include relaxation training, breathing retraining, cognitive therapy (generally for youths ages 9 to 17), and exposure-based practices to gradually reintroduce a child to school. These techniques have been strongly supported by randomized controlled trials specific to school refusal behavior2 and are useful for treating general anxiety and depression as well.

Parent-based contingency management techniques include establishing morning and evening routines, modifying parental commands toward brevity and clarity, providing attention-based consequences for school nonattendance (such as early bedtime, limited time with a parent at night), reducing excessive child questioning or reassurance-seeking behavior, and engaging in forced school attendance under strict conditions. Parent-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general29 but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Family-based techniques include developing written contracts to increase incentives for school attendance and decrease incentives for nonattendance, escorting a child to school and classes, and teaching youths to refuse offers from peers to miss school.30 As with parent-based techniques, family-based techniques have received strong support in the literature in general, but have been applied less frequently than child-based techniques to youths with school refusal behavior.

Gradual reintroduction to school

A preferred approach to resolve school refusal behavior usually involves gradual reintegration to school and classes. This may include initial attendance at lunchtime, 1 or 2 favorite classes, or in an alternative classroom setting such as a guidance counselor’s office or school library. Gradual reintegration into regular classrooms may then proceed.

If possible, a child should remain in school during the day and not be sent home unless intense medical symptoms are present.30 A recommended list of intense symptoms includes:

- frequent vomiting

- bleeding

- temperature >100° F

- severe diarrhea

- lice

- acute flu-like symptoms

- extreme medical conditions such as intense pain.

Case continued: a full-time student.

A structured diagnostic interview and other behavioral assessment measures show that Nathan meets criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. He worries excessively about his social and academic performance at school and displays several somatic complaints related to anxiety. His treatment thus involves a two-pronged approach:

- sertraline, 50 mg/d, which has been found to significantly reduce symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder in youths ages 5 to 17.

- child-based anxiety management techniques and family therapy to increase incentives for school attendance and limit fun activities during a school day spent at home.

His therapist and family physician collaborate with school personnel to gradually reintroduce Nathan to a full-time academic schedule.

- Copies of the child and parent versions of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised are available at www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=4322&UID=.

- King NJ, Bernstein GA. School refusal in children and adolescents: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:197-205.

- Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

- Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: a cognitive-behavioral therapy approach. Parent workbook/therapist’s guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Drug brand names

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Imipramine • Tofranil

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

Acknowledgment

Adapted and reprinted with permission from The Journal of Family Practice, August 2006, p 685-92.

1. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychol: Sci Prac 1996;3:339-54.

2. Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. Hansen C, Sanders SL, Massaro S, Last CG. Predictors of severity of absenteeism in children with anxiety-based school refusal. J Clin Child Psychol 1998;27:246-54.

4. Franklin CG, Soto I. Keeping Hispanic youths in school. Children & Schools 2002;24:139-43.

5. Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:797-807.

6. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry 2001;35:822-6.

7. Kearney CA, Albano AM. The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: diagnostic aspects. Behav Modif 2004;28:147-61.

8. Bernstein GA, Massie ED, Thuras PD, Perwien AR, Borchardt CM, Crosby RD. Somatic symptoms in anxious-depressed school refusers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:661-8.

9. Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and absenteeism related to respiratory illness in school children. Am J Epidemiology 2003;157:861-9.

10. Glaab LA, Brown R, Daneman D. School attendance in children with type I diabetes. Diabetic Med 2005;22:421-6.

11. Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterology 2004;99:2442-51.

12. Buitelaar JK, van Andel H, Duyx JHM, van Strien DC. Depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescence: a follow-up study of adolescents with school refusal. Acta Paedopsychiatrica 1994;56:249-53.

13. Flakierska-Praquin N, Lindstrom M, Gillberg C. School phobia with separation anxiety disorder: a comparative 20- to 29-year follow-up study of 35 school refusers. Comp Psychiatry 1997;38:17-22.

14. Hibbett A, Fogelman K. Future lives of truants: family formation and health-related behaviour. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:171-9.

15. Hibbett A, Fogelman K, Manor O. Occupational outcomes of truancy. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:23-36.

16. Kearney CA. Bridging the gap among professionals who address youth with school absenteeism: overview and suggestions for consensus. Prof Psychol Res Prac 2003;34:57-65.

17. King NJ, Heyne D, Tonge B, Gullone E, Ollendick TH. School refusal: categorical diagnoses, functional analysis and treatment planning. Clin Psychol Psychother 2001;8:352-60.

18. Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the School Refusal Assessment Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2002;24:235-45.

19. Kearney CA. Confirmatory factor analysis of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised: child and parent versions. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2006; in press.

20. Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM, Perwein AR, et al. Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2000;39:276-83.

21. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. A critical review of pharmacotherapy for youth with anxiety disorders: things are not as they seem. J Anxiety Disord 1998;12:83-102.

22. Layne AE, Bernstein GA, Egan EA, Kushner MG. Predictors of treatment response in anxious-depressed adolescents with school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2003;42:319-26.

23. Compton SN, Grant PJ, Chrisman AK, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: an open trial. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:564-71.

24. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-5.

25. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. Functionally-based prescriptive and nonprescriptive treatment for children and adolescents with school refusal behavior. Behav Ther 1999;30:673-95.

26. King NJ, Tonge BJ, Heyne D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school-refusing children: A controlled evaluation. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:395-403.

27. Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school phobia. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:404-11.

28. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-20.

29. Kearney CA, Roblek TL. Parent training in the treatment of school refusal behavior. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, eds. Handbook of parent training: parents as co-therapists for children’s behavior problems, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1998:225-56.

30. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach/Therapist’s guide. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 2000.

31. Kearney CA, Bates M. Addressing school refusal behavior: Suggestions for frontline professionals. Children & Schools 2005;27:207-16.

32. Astor RA, Benbenishty R, Zeira A, Vinokur A. School climate, observed risky behaviors, and victimization as predictors of high school students’ fear and judgments of school violence as a problem. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:716-36.

33. Glew GM, Fan M-Y, Katon W, Rivara FP, Kernic MA. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:1026-31.

34. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. The associations between victimization, feeling unsafe, and asthma episodes among US high-school students. Am J Public Health 2006;96:802-4.

1. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. The evolution and reconciliation of taxonomic strategies for school refusal behavior. Clin Psychol: Sci Prac 1996;3:339-54.

2. Kearney CA. School refusal behavior in youth: a functional approach to assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

3. Hansen C, Sanders SL, Massaro S, Last CG. Predictors of severity of absenteeism in children with anxiety-based school refusal. J Clin Child Psychol 1998;27:246-54.

4. Franklin CG, Soto I. Keeping Hispanic youths in school. Children & Schools 2002;24:139-43.

5. Egger HL, Costello EJ, Angold A. School refusal and psychiatric disorders: a community study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42:797-807.

6. McShane G, Walter G, Rey JM. Characteristics of adolescents with school refusal. Aust New Zeal J Psychiatry 2001;35:822-6.

7. Kearney CA, Albano AM. The functional profiles of school refusal behavior: diagnostic aspects. Behav Modif 2004;28:147-61.

8. Bernstein GA, Massie ED, Thuras PD, Perwien AR, Borchardt CM, Crosby RD. Somatic symptoms in anxious-depressed school refusers. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36:661-8.

9. Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and absenteeism related to respiratory illness in school children. Am J Epidemiology 2003;157:861-9.

10. Glaab LA, Brown R, Daneman D. School attendance in children with type I diabetes. Diabetic Med 2005;22:421-6.

11. Levy RL, Whitehead WE, Walker LS, et al. Increased somatic complaints and health-care utilization in children: effects of parent IBS status and parent response to gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterology 2004;99:2442-51.

12. Buitelaar JK, van Andel H, Duyx JHM, van Strien DC. Depressive and anxiety disorders in adolescence: a follow-up study of adolescents with school refusal. Acta Paedopsychiatrica 1994;56:249-53.

13. Flakierska-Praquin N, Lindstrom M, Gillberg C. School phobia with separation anxiety disorder: a comparative 20- to 29-year follow-up study of 35 school refusers. Comp Psychiatry 1997;38:17-22.

14. Hibbett A, Fogelman K. Future lives of truants: family formation and health-related behaviour. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:171-9.

15. Hibbett A, Fogelman K, Manor O. Occupational outcomes of truancy. Brit J Educ Psychology 1990;60:23-36.

16. Kearney CA. Bridging the gap among professionals who address youth with school absenteeism: overview and suggestions for consensus. Prof Psychol Res Prac 2003;34:57-65.

17. King NJ, Heyne D, Tonge B, Gullone E, Ollendick TH. School refusal: categorical diagnoses, functional analysis and treatment planning. Clin Psychol Psychother 2001;8:352-60.

18. Kearney CA. Identifying the function of school refusal behavior: a revision of the School Refusal Assessment Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2002;24:235-45.

19. Kearney CA. Confirmatory factor analysis of the School Refusal Assessment Scale-Revised: child and parent versions. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2006; in press.

20. Bernstein GA, Borchardt CM, Perwein AR, et al. Imipramine plus cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2000;39:276-83.

21. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. A critical review of pharmacotherapy for youth with anxiety disorders: things are not as they seem. J Anxiety Disord 1998;12:83-102.

22. Layne AE, Bernstein GA, Egan EA, Kushner MG. Predictors of treatment response in anxious-depressed adolescents with school refusal. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2003;42:319-26.

23. Compton SN, Grant PJ, Chrisman AK, et al. Sertraline in children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: an open trial. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:564-71.

24. Whittington CJ, Kendall T, Fonagy T, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in childhood depression: systematic review of published versus unpublished data. Lancet 2004;363:1341-5.

25. Kearney CA, Silverman WK. Functionally-based prescriptive and nonprescriptive treatment for children and adolescents with school refusal behavior. Behav Ther 1999;30:673-95.

26. King NJ, Tonge BJ, Heyne D, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school-refusing children: A controlled evaluation. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:395-403.

27. Last CG, Hansen C, Franco N. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of school phobia. J Am Acad Chil Adol Psychiatry 1998;37:404-11.

28. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-20.

29. Kearney CA, Roblek TL. Parent training in the treatment of school refusal behavior. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, eds. Handbook of parent training: parents as co-therapists for children’s behavior problems, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1998:225-56.

30. Kearney CA, Albano AM. When children refuse school: A cognitive-behavioral therapy approach/Therapist’s guide. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 2000.

31. Kearney CA, Bates M. Addressing school refusal behavior: Suggestions for frontline professionals. Children & Schools 2005;27:207-16.

32. Astor RA, Benbenishty R, Zeira A, Vinokur A. School climate, observed risky behaviors, and victimization as predictors of high school students’ fear and judgments of school violence as a problem. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:716-36.

33. Glew GM, Fan M-Y, Katon W, Rivara FP, Kernic MA. Bullying, psychosocial adjustment, and academic performance in elementary school. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:1026-31.

34. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. The associations between victimization, feeling unsafe, and asthma episodes among US high-school students. Am J Public Health 2006;96:802-4.