User login

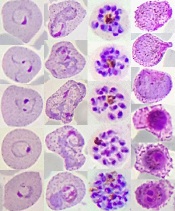

from patients in Thailand

Image by Wanlapa Roobsoong

Researchers say they have uncovered the global, evolving, and historic make-up of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax.

The group’s study revealed 4 genetically distinct populations of P vivax that provide insight into the movement of the parasite over time and

show how it is still adapting to regional variations in the mosquitoes that transmit P vivax, the humans infected with the parasite, and the drugs used to fight it.

“Our findings show it is evolving in response to antimalarial drugs and adapting to regional differences, indicating a wide range of approaches will likely be necessary to eliminate it globally,” said Jane Carlton, PhD, of New York University in New York, New York.

Dr Carlton and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

The researchers sequenced 182 DNA samples of P vivax collected from patients in 11 countries. The team said this provided new insights into the nature of P vivax as it exists today and also served as a “genetic history book” of the studied regions.

“The DNA data show that P vivax has clearly had a different history of association with global human populations than other malaria parasites, indicating that unique aspects of its biology may have influenced the ways in which it spread around the world,” said Daniel Neafsey, PhD, of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Specifically, the researchers found that Central and South American P vivax populations are genetically diverse and distinct from all other contemporary P vivax populations. The team said this suggests that New World parasites may have been introduced by colonial seafarers and represent a now-eliminated European parasite population.

The researchers also found that contemporary African and South Asian P vivax populations are genetically similar. They said this suggests that South Asian P vivax populations may have genetically mingled with European lineages during the colonial era, or it may reflect ancient connections between human populations in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, and Indian subcontinent.

Another finding was the relatively homogeneous genetic makeup of P vivax in Mexico, which reflects a steady decline of the disease in this country over the last decade.

By contrast, the Papua New Guinea population of P vivax was shown to be very diverse relative to other P vivax populations.

A similar study, which also illustrated the global variations of P vivax, was recently published in Nature Genetics in as well. ![]()

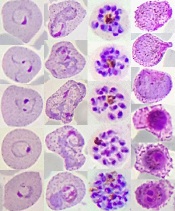

from patients in Thailand

Image by Wanlapa Roobsoong

Researchers say they have uncovered the global, evolving, and historic make-up of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax.

The group’s study revealed 4 genetically distinct populations of P vivax that provide insight into the movement of the parasite over time and

show how it is still adapting to regional variations in the mosquitoes that transmit P vivax, the humans infected with the parasite, and the drugs used to fight it.

“Our findings show it is evolving in response to antimalarial drugs and adapting to regional differences, indicating a wide range of approaches will likely be necessary to eliminate it globally,” said Jane Carlton, PhD, of New York University in New York, New York.

Dr Carlton and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

The researchers sequenced 182 DNA samples of P vivax collected from patients in 11 countries. The team said this provided new insights into the nature of P vivax as it exists today and also served as a “genetic history book” of the studied regions.

“The DNA data show that P vivax has clearly had a different history of association with global human populations than other malaria parasites, indicating that unique aspects of its biology may have influenced the ways in which it spread around the world,” said Daniel Neafsey, PhD, of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Specifically, the researchers found that Central and South American P vivax populations are genetically diverse and distinct from all other contemporary P vivax populations. The team said this suggests that New World parasites may have been introduced by colonial seafarers and represent a now-eliminated European parasite population.

The researchers also found that contemporary African and South Asian P vivax populations are genetically similar. They said this suggests that South Asian P vivax populations may have genetically mingled with European lineages during the colonial era, or it may reflect ancient connections between human populations in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, and Indian subcontinent.

Another finding was the relatively homogeneous genetic makeup of P vivax in Mexico, which reflects a steady decline of the disease in this country over the last decade.

By contrast, the Papua New Guinea population of P vivax was shown to be very diverse relative to other P vivax populations.

A similar study, which also illustrated the global variations of P vivax, was recently published in Nature Genetics in as well. ![]()

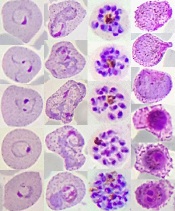

from patients in Thailand

Image by Wanlapa Roobsoong

Researchers say they have uncovered the global, evolving, and historic make-up of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax.

The group’s study revealed 4 genetically distinct populations of P vivax that provide insight into the movement of the parasite over time and

show how it is still adapting to regional variations in the mosquitoes that transmit P vivax, the humans infected with the parasite, and the drugs used to fight it.

“Our findings show it is evolving in response to antimalarial drugs and adapting to regional differences, indicating a wide range of approaches will likely be necessary to eliminate it globally,” said Jane Carlton, PhD, of New York University in New York, New York.

Dr Carlton and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

The researchers sequenced 182 DNA samples of P vivax collected from patients in 11 countries. The team said this provided new insights into the nature of P vivax as it exists today and also served as a “genetic history book” of the studied regions.

“The DNA data show that P vivax has clearly had a different history of association with global human populations than other malaria parasites, indicating that unique aspects of its biology may have influenced the ways in which it spread around the world,” said Daniel Neafsey, PhD, of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Specifically, the researchers found that Central and South American P vivax populations are genetically diverse and distinct from all other contemporary P vivax populations. The team said this suggests that New World parasites may have been introduced by colonial seafarers and represent a now-eliminated European parasite population.

The researchers also found that contemporary African and South Asian P vivax populations are genetically similar. They said this suggests that South Asian P vivax populations may have genetically mingled with European lineages during the colonial era, or it may reflect ancient connections between human populations in the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East, and Indian subcontinent.

Another finding was the relatively homogeneous genetic makeup of P vivax in Mexico, which reflects a steady decline of the disease in this country over the last decade.

By contrast, the Papua New Guinea population of P vivax was shown to be very diverse relative to other P vivax populations.

A similar study, which also illustrated the global variations of P vivax, was recently published in Nature Genetics in as well. ![]()