User login

Investigators studied close to 143,000 patients, encompassing more than 150,000 MDD episodes. Episodes of depression with suicidal behavior (MDD-SB) were compared to MDD episodes without suicidal behavior (MDD-non-SB).

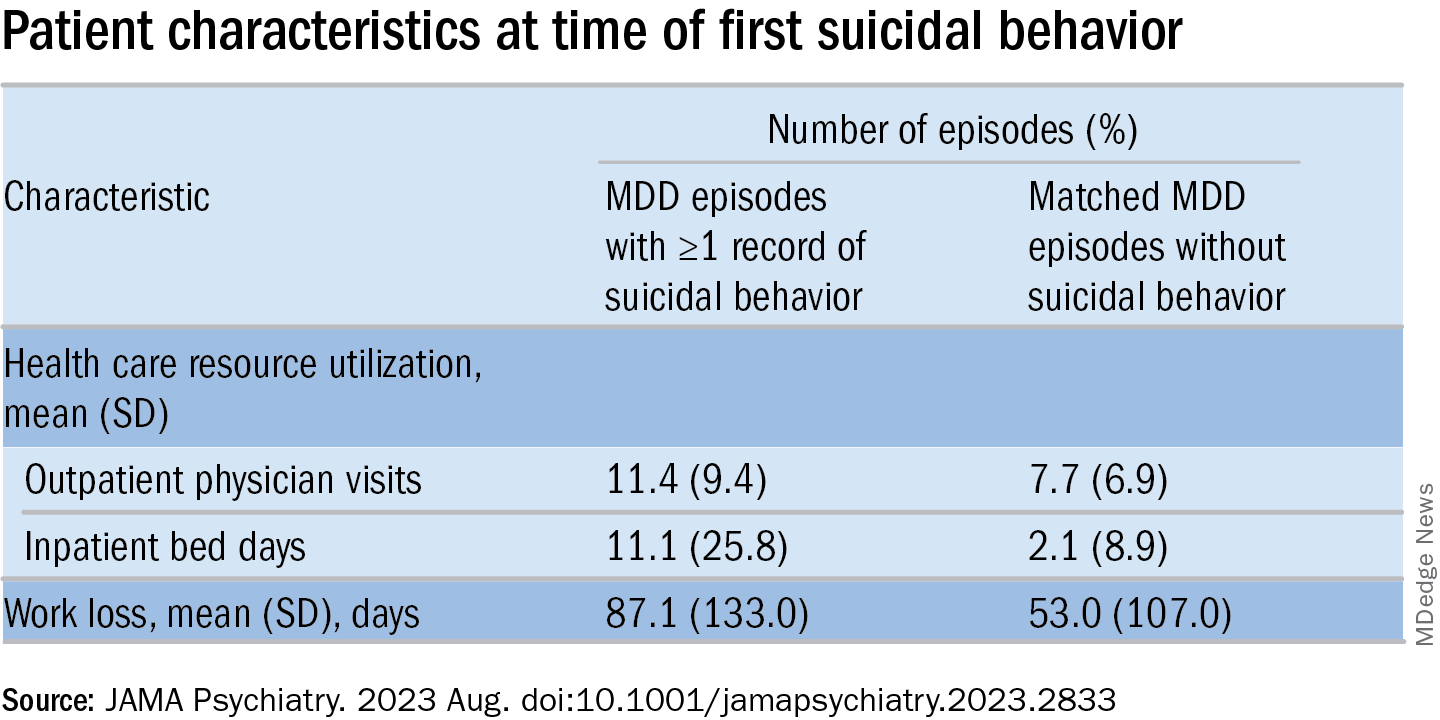

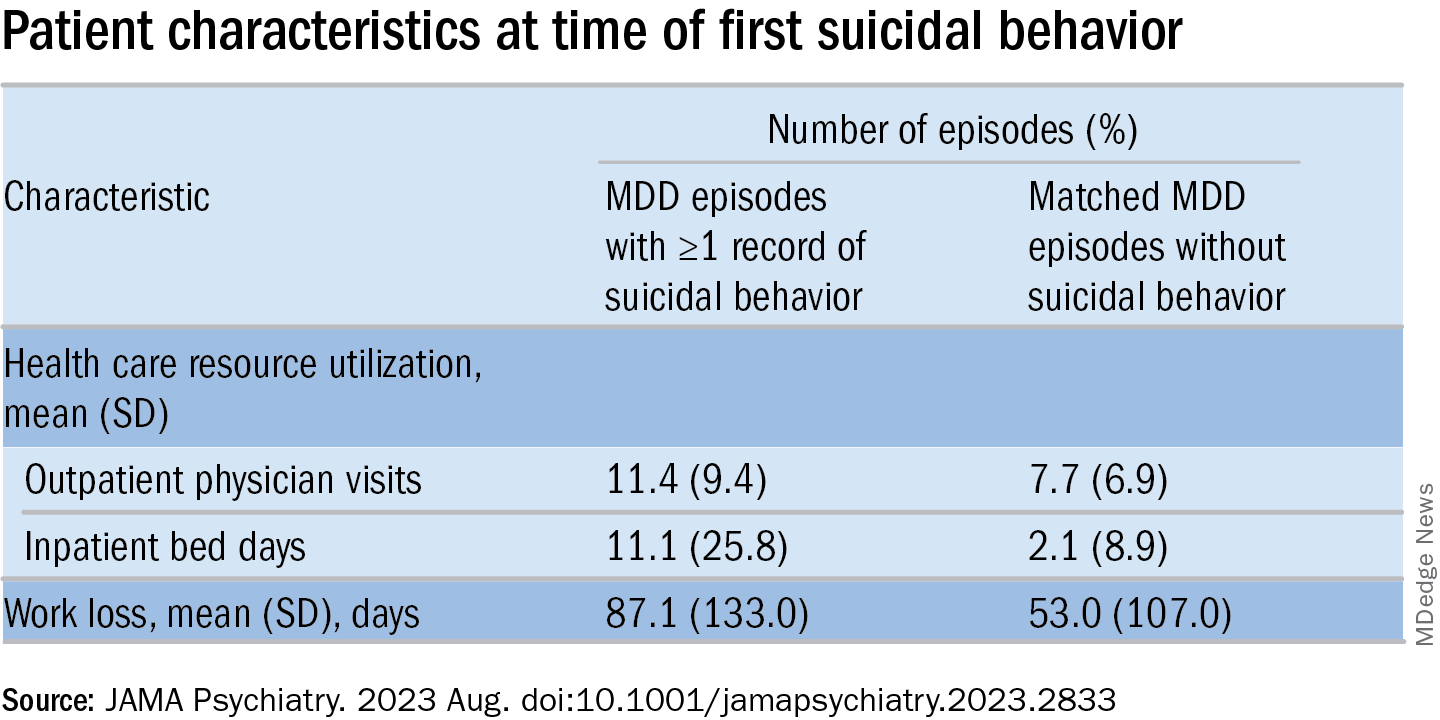

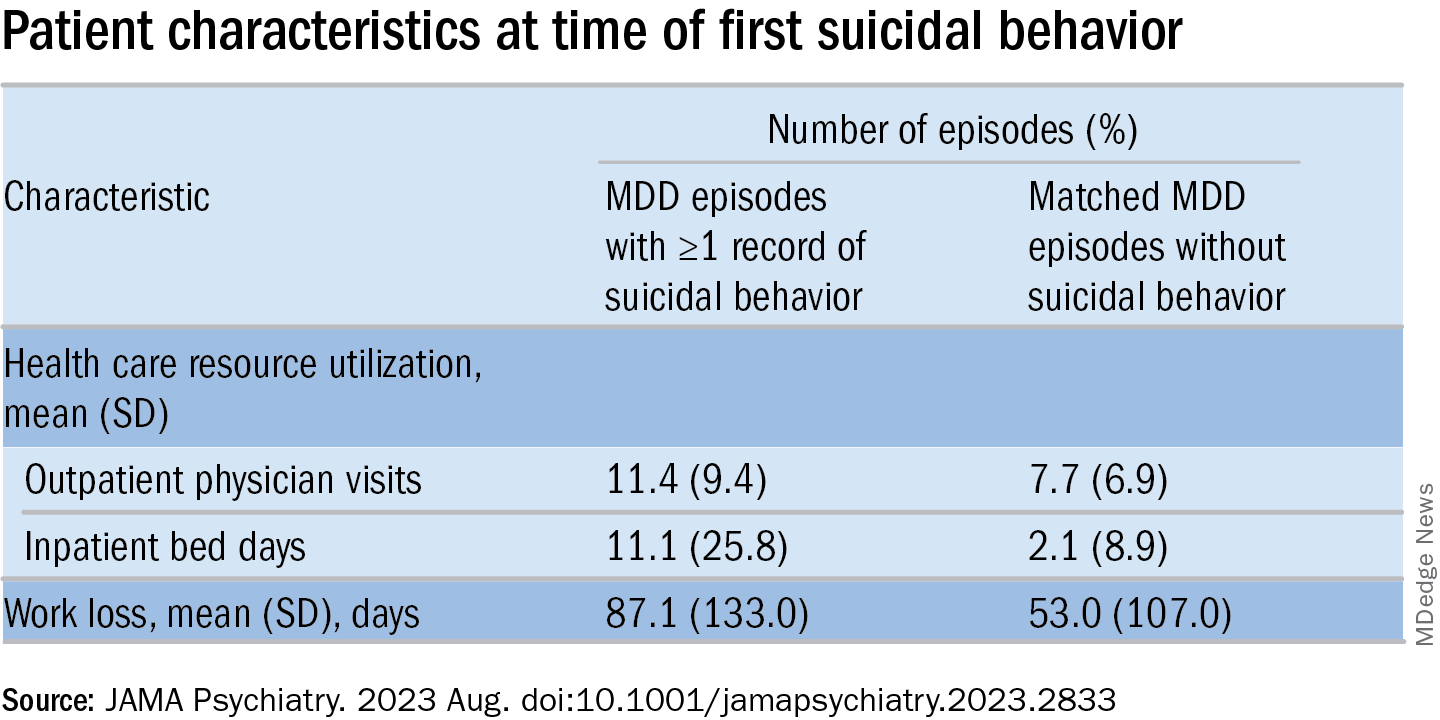

Suicidal behavior was associated with a 2.6-fold higher rate of all-cause mortality, as well as considerably higher health care resource utilization (HCRU) and work loss, compared with matched controls.

Patients with depression who had attempted suicide were younger and more commonly suffering from other psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and addiction. Important risk factors for suicidal acts within a year after the onset of a depressive episode were previous suicide attempts, substance use disorder, anxiety, and sleeping disorders.

“The findings tell us that the care provided for this particular group needs to be developed,” lead author Johan Lundberg, MD, PhD, adjunct professor in psychiatry and senior physician in psychiatry, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“The take-home message is that, when treating patients with increased risk of suicidal behavior, one should offer treatments with this in mind,” said Dr. Lundberg, also the head of the section of mood disorders, Northern Stockholm Psychiatry Clinic. “One possible option is lithium augmentation.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Identifying subgroups

Depression is associated with increased all-cause mortality, the authors write. Suicidal behavior and previous suicide attempts are known to increase the risk of suicide-associated mortality, with up to 13% of patients with nonfatal suicide attempts dying of suicide at a later time.

Previous studies investigating the association between suicidal behavior and mortality have been limited by nonrandom sampling due to “nonuniversal access to health care and/or exclusion of primary care data,” they state.

For this reason, it’s not established to what extent these estimates actually represent patients with MDD as a whole, or to what extent suicidal behavior is a risk factor for all-cause mortality.

“We think there is a need to identify subgroups within the very large group of individuals with MDD in order to improve treatment outcomes,” Dr. Lundberg said.

To do so, the researchers turned to data from the Stockholm MDD Cohort (SMC), which comprises all patients diagnosed with MDD in any health care setting in the regions of Stockholm from 2010 to 2018. They identified 5 years of recorded MDD episodes (n = 158,169) in patients aged 18 years and older (n = 145,577). A single patient could contribute more than one episode.

At index, MDD-SB patients (n = 2,219; mean age, 41 years) were matched with MDD-non-SB patients (9,574; mean age, 41 years) based on age, sex, year of MDD diagnosis, and socioeconomic status. In total, 2,219 episodes (63.2% in women, 36.8% in men) were compared to 11,109 episodes (63.4% in women, 36.6% in men), respectively.

Enhanced monitoring, optimized treatment

The median time from the start of the episode until the first suicidal behavior was 165 days.

The all-cause mortality rate in the MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB groups was 2.5 per 100 person-years vs. 1 per 100 person-years, respectively (based on 466 deaths), corresponding to a hazard ratio of 2.62 (95% confidence interval, 2.15-3.20).

Patients in the MDD-SB group were younger, were more frequently diagnosed while in specialized care, and had sustained more work loss than their counterparts in the MDD-non-SB group. They also showed a gradual increase in the prevalence of comorbid conditions from about 12 months before index, with this increase being “most pronounced” for anxiety, stress, substance use, and personality disorders.

MDD-SB episodes were associated with higher HCRU and more work loss, compared with MDD-non-SB episodes.

The researchers calculated a risk score for factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode (outcome). The two most important risk factors for suicidal behavior were a history of suicidal behavior together with age, which had a “U-shaped association” with the outcome, they write, with individuals younger than age 20 and older than age 70 having the highest risks.

The final risk score included additional factors that increased the risk of the outcome (in descending order): history of substance use, history of sleep disorders, health care level in which MDD was diagnosed, history of antidepressant use, and history of anxiety disorders.

These results “indicate that patients at risk for suicidal behavior can be identified at an early stage to allow for enhanced monitoring and optimized treatment with the goal of preventing suicidal behavior and reducing mortality,” the authors state.

The specific causes of death weren’t analyzed in this particular paper, Dr. Lundberg noted. A previous study conducted by the same group found the risk of death was doubled in MDD patients, compared with controls.

“We don’t speculate about which causes other than suicide might explain the difference” and account for the increased mortality risk, he said. “This should be studied in future projects.”

Complicated family of destructive behaviors

In a comment, Russell Copelan, MD, a former emergency department psychiatrist at the University of Colorado Affiliated Hospital and currently an expert consultant to the American Association of Suicidology, said a take-home message of the study is that suicide is “a complex and complicated family of destructive behaviors.”

The findings “should not suggest a wait-and-see clinical approach,” warned Dr. Copelan, who wasn’t involved with the study.

Underrecognized or misdiagnosed anxiety, agitation, and insomnia may be “barriers to remission and treatment response,” he noted.

Dr. Copelan, who is also the founder and CEO of eMed Logic, which offers assessment tools for suicide and violence, encouraged clinicians “not to minimize the proportion of patients who experience anxiety, agitation, and insomnia in response to what some may consider a personal misfortune, such as interpersonal, employment, or financial crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied close to 143,000 patients, encompassing more than 150,000 MDD episodes. Episodes of depression with suicidal behavior (MDD-SB) were compared to MDD episodes without suicidal behavior (MDD-non-SB).

Suicidal behavior was associated with a 2.6-fold higher rate of all-cause mortality, as well as considerably higher health care resource utilization (HCRU) and work loss, compared with matched controls.

Patients with depression who had attempted suicide were younger and more commonly suffering from other psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and addiction. Important risk factors for suicidal acts within a year after the onset of a depressive episode were previous suicide attempts, substance use disorder, anxiety, and sleeping disorders.

“The findings tell us that the care provided for this particular group needs to be developed,” lead author Johan Lundberg, MD, PhD, adjunct professor in psychiatry and senior physician in psychiatry, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“The take-home message is that, when treating patients with increased risk of suicidal behavior, one should offer treatments with this in mind,” said Dr. Lundberg, also the head of the section of mood disorders, Northern Stockholm Psychiatry Clinic. “One possible option is lithium augmentation.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Identifying subgroups

Depression is associated with increased all-cause mortality, the authors write. Suicidal behavior and previous suicide attempts are known to increase the risk of suicide-associated mortality, with up to 13% of patients with nonfatal suicide attempts dying of suicide at a later time.

Previous studies investigating the association between suicidal behavior and mortality have been limited by nonrandom sampling due to “nonuniversal access to health care and/or exclusion of primary care data,” they state.

For this reason, it’s not established to what extent these estimates actually represent patients with MDD as a whole, or to what extent suicidal behavior is a risk factor for all-cause mortality.

“We think there is a need to identify subgroups within the very large group of individuals with MDD in order to improve treatment outcomes,” Dr. Lundberg said.

To do so, the researchers turned to data from the Stockholm MDD Cohort (SMC), which comprises all patients diagnosed with MDD in any health care setting in the regions of Stockholm from 2010 to 2018. They identified 5 years of recorded MDD episodes (n = 158,169) in patients aged 18 years and older (n = 145,577). A single patient could contribute more than one episode.

At index, MDD-SB patients (n = 2,219; mean age, 41 years) were matched with MDD-non-SB patients (9,574; mean age, 41 years) based on age, sex, year of MDD diagnosis, and socioeconomic status. In total, 2,219 episodes (63.2% in women, 36.8% in men) were compared to 11,109 episodes (63.4% in women, 36.6% in men), respectively.

Enhanced monitoring, optimized treatment

The median time from the start of the episode until the first suicidal behavior was 165 days.

The all-cause mortality rate in the MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB groups was 2.5 per 100 person-years vs. 1 per 100 person-years, respectively (based on 466 deaths), corresponding to a hazard ratio of 2.62 (95% confidence interval, 2.15-3.20).

Patients in the MDD-SB group were younger, were more frequently diagnosed while in specialized care, and had sustained more work loss than their counterparts in the MDD-non-SB group. They also showed a gradual increase in the prevalence of comorbid conditions from about 12 months before index, with this increase being “most pronounced” for anxiety, stress, substance use, and personality disorders.

MDD-SB episodes were associated with higher HCRU and more work loss, compared with MDD-non-SB episodes.

The researchers calculated a risk score for factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode (outcome). The two most important risk factors for suicidal behavior were a history of suicidal behavior together with age, which had a “U-shaped association” with the outcome, they write, with individuals younger than age 20 and older than age 70 having the highest risks.

The final risk score included additional factors that increased the risk of the outcome (in descending order): history of substance use, history of sleep disorders, health care level in which MDD was diagnosed, history of antidepressant use, and history of anxiety disorders.

These results “indicate that patients at risk for suicidal behavior can be identified at an early stage to allow for enhanced monitoring and optimized treatment with the goal of preventing suicidal behavior and reducing mortality,” the authors state.

The specific causes of death weren’t analyzed in this particular paper, Dr. Lundberg noted. A previous study conducted by the same group found the risk of death was doubled in MDD patients, compared with controls.

“We don’t speculate about which causes other than suicide might explain the difference” and account for the increased mortality risk, he said. “This should be studied in future projects.”

Complicated family of destructive behaviors

In a comment, Russell Copelan, MD, a former emergency department psychiatrist at the University of Colorado Affiliated Hospital and currently an expert consultant to the American Association of Suicidology, said a take-home message of the study is that suicide is “a complex and complicated family of destructive behaviors.”

The findings “should not suggest a wait-and-see clinical approach,” warned Dr. Copelan, who wasn’t involved with the study.

Underrecognized or misdiagnosed anxiety, agitation, and insomnia may be “barriers to remission and treatment response,” he noted.

Dr. Copelan, who is also the founder and CEO of eMed Logic, which offers assessment tools for suicide and violence, encouraged clinicians “not to minimize the proportion of patients who experience anxiety, agitation, and insomnia in response to what some may consider a personal misfortune, such as interpersonal, employment, or financial crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators studied close to 143,000 patients, encompassing more than 150,000 MDD episodes. Episodes of depression with suicidal behavior (MDD-SB) were compared to MDD episodes without suicidal behavior (MDD-non-SB).

Suicidal behavior was associated with a 2.6-fold higher rate of all-cause mortality, as well as considerably higher health care resource utilization (HCRU) and work loss, compared with matched controls.

Patients with depression who had attempted suicide were younger and more commonly suffering from other psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety and addiction. Important risk factors for suicidal acts within a year after the onset of a depressive episode were previous suicide attempts, substance use disorder, anxiety, and sleeping disorders.

“The findings tell us that the care provided for this particular group needs to be developed,” lead author Johan Lundberg, MD, PhD, adjunct professor in psychiatry and senior physician in psychiatry, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, told this news organization.

“The take-home message is that, when treating patients with increased risk of suicidal behavior, one should offer treatments with this in mind,” said Dr. Lundberg, also the head of the section of mood disorders, Northern Stockholm Psychiatry Clinic. “One possible option is lithium augmentation.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Identifying subgroups

Depression is associated with increased all-cause mortality, the authors write. Suicidal behavior and previous suicide attempts are known to increase the risk of suicide-associated mortality, with up to 13% of patients with nonfatal suicide attempts dying of suicide at a later time.

Previous studies investigating the association between suicidal behavior and mortality have been limited by nonrandom sampling due to “nonuniversal access to health care and/or exclusion of primary care data,” they state.

For this reason, it’s not established to what extent these estimates actually represent patients with MDD as a whole, or to what extent suicidal behavior is a risk factor for all-cause mortality.

“We think there is a need to identify subgroups within the very large group of individuals with MDD in order to improve treatment outcomes,” Dr. Lundberg said.

To do so, the researchers turned to data from the Stockholm MDD Cohort (SMC), which comprises all patients diagnosed with MDD in any health care setting in the regions of Stockholm from 2010 to 2018. They identified 5 years of recorded MDD episodes (n = 158,169) in patients aged 18 years and older (n = 145,577). A single patient could contribute more than one episode.

At index, MDD-SB patients (n = 2,219; mean age, 41 years) were matched with MDD-non-SB patients (9,574; mean age, 41 years) based on age, sex, year of MDD diagnosis, and socioeconomic status. In total, 2,219 episodes (63.2% in women, 36.8% in men) were compared to 11,109 episodes (63.4% in women, 36.6% in men), respectively.

Enhanced monitoring, optimized treatment

The median time from the start of the episode until the first suicidal behavior was 165 days.

The all-cause mortality rate in the MDD-SB and MDD-non-SB groups was 2.5 per 100 person-years vs. 1 per 100 person-years, respectively (based on 466 deaths), corresponding to a hazard ratio of 2.62 (95% confidence interval, 2.15-3.20).

Patients in the MDD-SB group were younger, were more frequently diagnosed while in specialized care, and had sustained more work loss than their counterparts in the MDD-non-SB group. They also showed a gradual increase in the prevalence of comorbid conditions from about 12 months before index, with this increase being “most pronounced” for anxiety, stress, substance use, and personality disorders.

MDD-SB episodes were associated with higher HCRU and more work loss, compared with MDD-non-SB episodes.

The researchers calculated a risk score for factors associated with suicidal behavior within 1 year after the start of an MDD episode (outcome). The two most important risk factors for suicidal behavior were a history of suicidal behavior together with age, which had a “U-shaped association” with the outcome, they write, with individuals younger than age 20 and older than age 70 having the highest risks.

The final risk score included additional factors that increased the risk of the outcome (in descending order): history of substance use, history of sleep disorders, health care level in which MDD was diagnosed, history of antidepressant use, and history of anxiety disorders.

These results “indicate that patients at risk for suicidal behavior can be identified at an early stage to allow for enhanced monitoring and optimized treatment with the goal of preventing suicidal behavior and reducing mortality,” the authors state.

The specific causes of death weren’t analyzed in this particular paper, Dr. Lundberg noted. A previous study conducted by the same group found the risk of death was doubled in MDD patients, compared with controls.

“We don’t speculate about which causes other than suicide might explain the difference” and account for the increased mortality risk, he said. “This should be studied in future projects.”

Complicated family of destructive behaviors

In a comment, Russell Copelan, MD, a former emergency department psychiatrist at the University of Colorado Affiliated Hospital and currently an expert consultant to the American Association of Suicidology, said a take-home message of the study is that suicide is “a complex and complicated family of destructive behaviors.”

The findings “should not suggest a wait-and-see clinical approach,” warned Dr. Copelan, who wasn’t involved with the study.

Underrecognized or misdiagnosed anxiety, agitation, and insomnia may be “barriers to remission and treatment response,” he noted.

Dr. Copelan, who is also the founder and CEO of eMed Logic, which offers assessment tools for suicide and violence, encouraged clinicians “not to minimize the proportion of patients who experience anxiety, agitation, and insomnia in response to what some may consider a personal misfortune, such as interpersonal, employment, or financial crisis.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY