User login

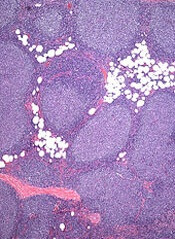

Genetic profiling has provided a clearer picture of follicular lymphoma (FL) development and progression, according to research published in Nature Genetics.

Investigators performed whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of samples from FL patients and found a number of mutations that appeared to be responsible for disease onset.

The team also identified mutations that seemed to drive FL toward a more aggressive form.

They said these findings provide a number of new therapeutic targets that may stop FL from becoming aggressive or developing resistance to treatment.

“Resistance to treatment is a major problem for follicular lymphoma patients, as they often respond well to treatment and later relapse,” said study author Jude Fitzgibbon, PhD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London, England.

“[This] gives the cancer multiple opportunities to evolve into a more aggressive and more difficult-to-treat form of the disease. We’ve been able to chronicle the chain of genetic events that leads to aggressive forms of the disease. If we can develop treatments to prevent some of these changes from taking place, we should be able to stop the cancer in its tracks.”

Dr Fitzgibbon and his colleagues performed whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing of sequential FL and transformed FL pairs and matched germline samples from 10 FL cases with deep-targeted sequencing of 28 genes in an extension cohort.

Among the 10 cases, the researchers identified 1560 protein-altering variants affecting 908 genes, including missense changes (84.8%), short indels (8.9%), and nonsense mutations (6.3%).

Patterns of evolution

The investigators constructed phylogenetic trees for the 10 FL cases and discovered a common progenitor clone (CPC), as well as 2 patterns of evolution.

Eight of the cases exhibited evolution through a “rich” ancestral CPC, showing high clonal semblance between the FL and transformed-FL tumors. The other 2 cases showed evolution through a “sparse” CPC, with only 4 nonsynonymous mutations shared by the FL and transformed-FL samples.

These 2 patterns of evolution shared mutations in 3 genes—KMT2D, TNFRSF14, and CREBBP. According to the researchers, this suggests tumor dependency on these alterations during lymphomagenesis and progression.

Mutation prevalence, timing

The investigators then set out to determine the prevalence of the mutations they identified in the 10 cases. They performed deep-targeted resequencing of 28 candidate genes in an extension cohort of 100 independent FL biopsies and 32 paired FL-transformed FL cases (including the 10 index cases).

More than 70% of cases had concurrent mutations in at least 2 of the histone-modifying enzymes screened (CREBBP, EZH2, MEF2B, and KMT2D).

Twenty-eight percent of cases had mutations affecting at least one histone H1 gene. HIST1H1C and HIST1H1E were the most frequently mutated.

The researchers also saw frequent mutations in components of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, including STAT6 (12%) and SOCS1 (8%).

They found mutually exclusive mutations in the NF-κB signaling pathway in a third of FLs, including CARD11 (11%) and TNFAIP3 (11%).

And 17% of cases had mutations in genes important for B-cell development, including Ebf1.

Finally, the investigators set out to differentiate early genetic events from late ones. They found that mutations in histone-modifying genes—KMT2D, CREBBP, and EZH2—as well as mutations in STAT6 and TNFRSF14 were predominantly clonal events.

On the other hand, mutations in EBF1 and regulators of NF-κB signaling—MYD88 and TNFAIP3—were gained at transformation.

“This study has uncovered some of the key molecular changes taking place [in FL] and offers new targets for treating the disease,” said Nell Barrie, of Cancer Research UK, the organization that funded this study.

“Research into the genetics that underpin cancer is helping us to better know the enemy and find new ways in which we might beat it.” ![]()

Genetic profiling has provided a clearer picture of follicular lymphoma (FL) development and progression, according to research published in Nature Genetics.

Investigators performed whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of samples from FL patients and found a number of mutations that appeared to be responsible for disease onset.

The team also identified mutations that seemed to drive FL toward a more aggressive form.

They said these findings provide a number of new therapeutic targets that may stop FL from becoming aggressive or developing resistance to treatment.

“Resistance to treatment is a major problem for follicular lymphoma patients, as they often respond well to treatment and later relapse,” said study author Jude Fitzgibbon, PhD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London, England.

“[This] gives the cancer multiple opportunities to evolve into a more aggressive and more difficult-to-treat form of the disease. We’ve been able to chronicle the chain of genetic events that leads to aggressive forms of the disease. If we can develop treatments to prevent some of these changes from taking place, we should be able to stop the cancer in its tracks.”

Dr Fitzgibbon and his colleagues performed whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing of sequential FL and transformed FL pairs and matched germline samples from 10 FL cases with deep-targeted sequencing of 28 genes in an extension cohort.

Among the 10 cases, the researchers identified 1560 protein-altering variants affecting 908 genes, including missense changes (84.8%), short indels (8.9%), and nonsense mutations (6.3%).

Patterns of evolution

The investigators constructed phylogenetic trees for the 10 FL cases and discovered a common progenitor clone (CPC), as well as 2 patterns of evolution.

Eight of the cases exhibited evolution through a “rich” ancestral CPC, showing high clonal semblance between the FL and transformed-FL tumors. The other 2 cases showed evolution through a “sparse” CPC, with only 4 nonsynonymous mutations shared by the FL and transformed-FL samples.

These 2 patterns of evolution shared mutations in 3 genes—KMT2D, TNFRSF14, and CREBBP. According to the researchers, this suggests tumor dependency on these alterations during lymphomagenesis and progression.

Mutation prevalence, timing

The investigators then set out to determine the prevalence of the mutations they identified in the 10 cases. They performed deep-targeted resequencing of 28 candidate genes in an extension cohort of 100 independent FL biopsies and 32 paired FL-transformed FL cases (including the 10 index cases).

More than 70% of cases had concurrent mutations in at least 2 of the histone-modifying enzymes screened (CREBBP, EZH2, MEF2B, and KMT2D).

Twenty-eight percent of cases had mutations affecting at least one histone H1 gene. HIST1H1C and HIST1H1E were the most frequently mutated.

The researchers also saw frequent mutations in components of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, including STAT6 (12%) and SOCS1 (8%).

They found mutually exclusive mutations in the NF-κB signaling pathway in a third of FLs, including CARD11 (11%) and TNFAIP3 (11%).

And 17% of cases had mutations in genes important for B-cell development, including Ebf1.

Finally, the investigators set out to differentiate early genetic events from late ones. They found that mutations in histone-modifying genes—KMT2D, CREBBP, and EZH2—as well as mutations in STAT6 and TNFRSF14 were predominantly clonal events.

On the other hand, mutations in EBF1 and regulators of NF-κB signaling—MYD88 and TNFAIP3—were gained at transformation.

“This study has uncovered some of the key molecular changes taking place [in FL] and offers new targets for treating the disease,” said Nell Barrie, of Cancer Research UK, the organization that funded this study.

“Research into the genetics that underpin cancer is helping us to better know the enemy and find new ways in which we might beat it.” ![]()

Genetic profiling has provided a clearer picture of follicular lymphoma (FL) development and progression, according to research published in Nature Genetics.

Investigators performed whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing of samples from FL patients and found a number of mutations that appeared to be responsible for disease onset.

The team also identified mutations that seemed to drive FL toward a more aggressive form.

They said these findings provide a number of new therapeutic targets that may stop FL from becoming aggressive or developing resistance to treatment.

“Resistance to treatment is a major problem for follicular lymphoma patients, as they often respond well to treatment and later relapse,” said study author Jude Fitzgibbon, PhD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London, England.

“[This] gives the cancer multiple opportunities to evolve into a more aggressive and more difficult-to-treat form of the disease. We’ve been able to chronicle the chain of genetic events that leads to aggressive forms of the disease. If we can develop treatments to prevent some of these changes from taking place, we should be able to stop the cancer in its tracks.”

Dr Fitzgibbon and his colleagues performed whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing of sequential FL and transformed FL pairs and matched germline samples from 10 FL cases with deep-targeted sequencing of 28 genes in an extension cohort.

Among the 10 cases, the researchers identified 1560 protein-altering variants affecting 908 genes, including missense changes (84.8%), short indels (8.9%), and nonsense mutations (6.3%).

Patterns of evolution

The investigators constructed phylogenetic trees for the 10 FL cases and discovered a common progenitor clone (CPC), as well as 2 patterns of evolution.

Eight of the cases exhibited evolution through a “rich” ancestral CPC, showing high clonal semblance between the FL and transformed-FL tumors. The other 2 cases showed evolution through a “sparse” CPC, with only 4 nonsynonymous mutations shared by the FL and transformed-FL samples.

These 2 patterns of evolution shared mutations in 3 genes—KMT2D, TNFRSF14, and CREBBP. According to the researchers, this suggests tumor dependency on these alterations during lymphomagenesis and progression.

Mutation prevalence, timing

The investigators then set out to determine the prevalence of the mutations they identified in the 10 cases. They performed deep-targeted resequencing of 28 candidate genes in an extension cohort of 100 independent FL biopsies and 32 paired FL-transformed FL cases (including the 10 index cases).

More than 70% of cases had concurrent mutations in at least 2 of the histone-modifying enzymes screened (CREBBP, EZH2, MEF2B, and KMT2D).

Twenty-eight percent of cases had mutations affecting at least one histone H1 gene. HIST1H1C and HIST1H1E were the most frequently mutated.

The researchers also saw frequent mutations in components of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, including STAT6 (12%) and SOCS1 (8%).

They found mutually exclusive mutations in the NF-κB signaling pathway in a third of FLs, including CARD11 (11%) and TNFAIP3 (11%).

And 17% of cases had mutations in genes important for B-cell development, including Ebf1.

Finally, the investigators set out to differentiate early genetic events from late ones. They found that mutations in histone-modifying genes—KMT2D, CREBBP, and EZH2—as well as mutations in STAT6 and TNFRSF14 were predominantly clonal events.

On the other hand, mutations in EBF1 and regulators of NF-κB signaling—MYD88 and TNFAIP3—were gained at transformation.

“This study has uncovered some of the key molecular changes taking place [in FL] and offers new targets for treating the disease,” said Nell Barrie, of Cancer Research UK, the organization that funded this study.

“Research into the genetics that underpin cancer is helping us to better know the enemy and find new ways in which we might beat it.” ![]()