User login

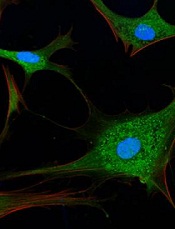

Image by Sarah Pfau

Research published in Cell has revealed a new function of genes in the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, and investigators believe this finding could have

implications for the treatment of FA and related disorders.

The team found that FA genes are required for selective autophagy.

In particular, the FANCC gene plays a key role in 2 types of selective autophagy: virophagy (the removal of viruses inside the cell) and mitophagy (the removal of mitochondria).

Experiments in mice showed that genetic deletion of FANCC blocks virophagy and increases the animals’ susceptibility to lethal viral encephalitis.

The investigators also found that FANCC protein is required for the clearance of damaged mitochondria and decreases the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and inflammasome activation.

And other genes in the FA pathway are required for mitophagy as well—FANCA, FANCF, FANCL, FANCD2, BRCA1, and BRCA2.

“There’s increasing evidence that the failure of cells to appropriately clear damaged mitochondria leads to abnormal activation of the inflammasome—a process that is emerging as an important contributor to many different diseases,” said study author Beth Levine, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas.

“The finding that FA genes function in clearing mitochondria and decreasing inflammasome activation provides a potential new inflammasome-targeted avenue of therapy for patients with diseases related to mutations in the FA genes.”

FA pathway genes were already known to play a role in DNA repair. The investigators said this new link to autophagy opens up unexplored horizons for understanding the function of these genes in human health and disease.

“Our findings suggest a novel mechanism by which mutations in FA genes may lead to the clinical manifestations in patients with FA and to cancers in patients with mutations in FA genes,” said study author Rhea Sumpter, MD, PhD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“We’ve shown that this new function of the FA genes in the selective autophagy pathways does not depend on their role in DNA repair.”

In addition, the autophagy function may partly explain why patients with FA are highly susceptible to infection and cancer, Dr Levine said.

While further research is needed to understand how these findings may be used to treat disease, the investigators said they have identified a novel avenue for developing potential therapies for FA and cancer patients.

“I believe the clearest therapeutic possibilities to come from our study results are the development of new FA agents that target the inflammasome and production of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), a pro-inflammatory cytokine,” Dr Sumpter said.

“Clinically, IL-1β signaling has been targeted with FDA-approved drugs very successfully in several auto-inflammatory diseases that involve excessive inflammasome activation. Our results suggest that FA patients may also benefit from these therapies.” ![]()

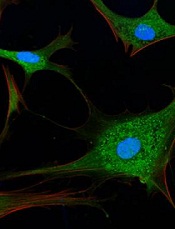

Image by Sarah Pfau

Research published in Cell has revealed a new function of genes in the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, and investigators believe this finding could have

implications for the treatment of FA and related disorders.

The team found that FA genes are required for selective autophagy.

In particular, the FANCC gene plays a key role in 2 types of selective autophagy: virophagy (the removal of viruses inside the cell) and mitophagy (the removal of mitochondria).

Experiments in mice showed that genetic deletion of FANCC blocks virophagy and increases the animals’ susceptibility to lethal viral encephalitis.

The investigators also found that FANCC protein is required for the clearance of damaged mitochondria and decreases the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and inflammasome activation.

And other genes in the FA pathway are required for mitophagy as well—FANCA, FANCF, FANCL, FANCD2, BRCA1, and BRCA2.

“There’s increasing evidence that the failure of cells to appropriately clear damaged mitochondria leads to abnormal activation of the inflammasome—a process that is emerging as an important contributor to many different diseases,” said study author Beth Levine, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas.

“The finding that FA genes function in clearing mitochondria and decreasing inflammasome activation provides a potential new inflammasome-targeted avenue of therapy for patients with diseases related to mutations in the FA genes.”

FA pathway genes were already known to play a role in DNA repair. The investigators said this new link to autophagy opens up unexplored horizons for understanding the function of these genes in human health and disease.

“Our findings suggest a novel mechanism by which mutations in FA genes may lead to the clinical manifestations in patients with FA and to cancers in patients with mutations in FA genes,” said study author Rhea Sumpter, MD, PhD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“We’ve shown that this new function of the FA genes in the selective autophagy pathways does not depend on their role in DNA repair.”

In addition, the autophagy function may partly explain why patients with FA are highly susceptible to infection and cancer, Dr Levine said.

While further research is needed to understand how these findings may be used to treat disease, the investigators said they have identified a novel avenue for developing potential therapies for FA and cancer patients.

“I believe the clearest therapeutic possibilities to come from our study results are the development of new FA agents that target the inflammasome and production of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), a pro-inflammatory cytokine,” Dr Sumpter said.

“Clinically, IL-1β signaling has been targeted with FDA-approved drugs very successfully in several auto-inflammatory diseases that involve excessive inflammasome activation. Our results suggest that FA patients may also benefit from these therapies.” ![]()

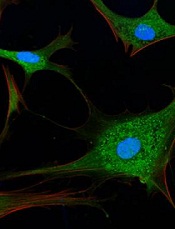

Image by Sarah Pfau

Research published in Cell has revealed a new function of genes in the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, and investigators believe this finding could have

implications for the treatment of FA and related disorders.

The team found that FA genes are required for selective autophagy.

In particular, the FANCC gene plays a key role in 2 types of selective autophagy: virophagy (the removal of viruses inside the cell) and mitophagy (the removal of mitochondria).

Experiments in mice showed that genetic deletion of FANCC blocks virophagy and increases the animals’ susceptibility to lethal viral encephalitis.

The investigators also found that FANCC protein is required for the clearance of damaged mitochondria and decreases the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and inflammasome activation.

And other genes in the FA pathway are required for mitophagy as well—FANCA, FANCF, FANCL, FANCD2, BRCA1, and BRCA2.

“There’s increasing evidence that the failure of cells to appropriately clear damaged mitochondria leads to abnormal activation of the inflammasome—a process that is emerging as an important contributor to many different diseases,” said study author Beth Levine, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas.

“The finding that FA genes function in clearing mitochondria and decreasing inflammasome activation provides a potential new inflammasome-targeted avenue of therapy for patients with diseases related to mutations in the FA genes.”

FA pathway genes were already known to play a role in DNA repair. The investigators said this new link to autophagy opens up unexplored horizons for understanding the function of these genes in human health and disease.

“Our findings suggest a novel mechanism by which mutations in FA genes may lead to the clinical manifestations in patients with FA and to cancers in patients with mutations in FA genes,” said study author Rhea Sumpter, MD, PhD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

“We’ve shown that this new function of the FA genes in the selective autophagy pathways does not depend on their role in DNA repair.”

In addition, the autophagy function may partly explain why patients with FA are highly susceptible to infection and cancer, Dr Levine said.

While further research is needed to understand how these findings may be used to treat disease, the investigators said they have identified a novel avenue for developing potential therapies for FA and cancer patients.

“I believe the clearest therapeutic possibilities to come from our study results are the development of new FA agents that target the inflammasome and production of interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), a pro-inflammatory cytokine,” Dr Sumpter said.

“Clinically, IL-1β signaling has been targeted with FDA-approved drugs very successfully in several auto-inflammatory diseases that involve excessive inflammasome activation. Our results suggest that FA patients may also benefit from these therapies.” ![]()