User login

When patient monitor alarms sound too many times, it can discourage using the very monitors that are intended to keep patients safe and inform clinicians of a patient’s physiological state. However, research shows that using "smart alarm" technology and getting smart about alarm monitors can reduce clinically insignificant alarms.

According to Dr. Paul M. Schyve, senior adviser for health care improvement at the Joint Commission, "There is uniform agreement that alarm fatigue is a major problem. Alarm systems are built into many medical devices, such as infusion pumps and ventilators. When they work as intended, they alert caregivers that a decision or action is required for the patient’s health and safety. However, too many alarms, including false alarms, can fatigue, confuse, and overload clinicians."

It is therefore no surprise that alarm fatigue has yet again been designated as the number one health technology hazard for 2013 by ECRI Institute, an independent, nonprofit organization that researches the best approaches to improving the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of patient care.

ECRI conducted an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration’s database of adverse events involving medical devices, and found 216 deaths nationwide from 2005 to the middle of 2010 in which problems with monitor alarms occurred. This number of deaths is thought to be low because of underreporting by the health care industry. ECRI found 13 more cases in its own database, which it compiles from incident investigations on behalf of hospital clients and from its own voluntary reporting system.

"Alarms provide a technological safety net," observed Maria Cvach, R.N., M.S.N, assistant director of nursing and clinical standards at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. "Reliance on physiological monitors to continuously ‘watch’ patients and to alert the nurse when a serious rhythm problem occurs is standard practice on monitored units. Alarms are intended to alert clinicians to deviations from a predetermined ‘normal’ status," she said.

However, alarm fatigue may occur when the sheer number of monitor alarms overwhelms caregivers. "When alarm frequency is high, nurses are at risk for becoming desensitized to the alarms that are intended to protect their patients," said Ms. Cvach.

Here are three tips to help reduce false alarms.

Use ‘Smart Alarm’ Technology

Using "smart alarm" technology that brings together a number of physiological parameters may recognize and reduce clinically insignificant alarms while accurately reflecting the patient’s condition and preserving clinically significant alarm vigilance.

"Nurses in intensive care units stated that the primary problem with alarms is that they are continuously going off, and that the largest contributor to the number of false alarms in intensive care units is the pulse oximetry alarm," said Ms. Cvach. "A ‘smart alarm’ that analyzed multiple parameters, like oxygenation and adequacy of ventilation, in a patient’s condition, may be a solution. This would increase patient safety by making it easier for nurses to assess a patient’s condition and reduce the frequency of false alarms."

Using Ms. Cvach’s example, don’t let the fear of alarms prevent you from using monitors to assess both oxygenation with pulse oximetry and the adequacy of ventilation with capnography. Using technology that incorporates multiple parameters (such as, etCO2 [end tidal CO2], SpO2, respiratory rate, and pulse rate) into a single parameter would not only make it easier to quickly identify a patient’s status, but also decrease the number of clinically insignificant alarms.

Having technology that helps rather than hinders patient care through too many false alarms would increase patient safety and improve health outcomes. Use "smart alarm" technology to decrease alarm fatigue and increase patient safety.

Reduce Alarm Duplication

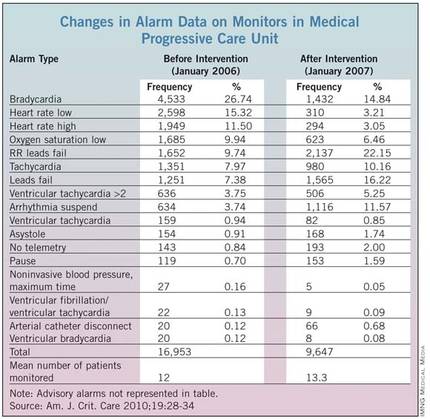

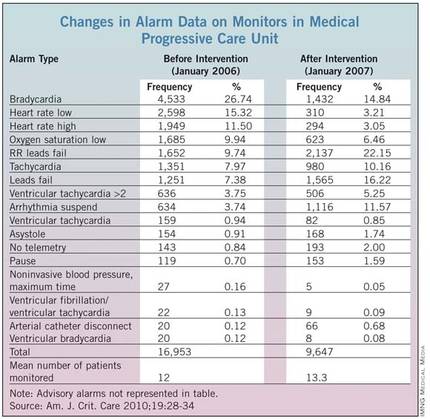

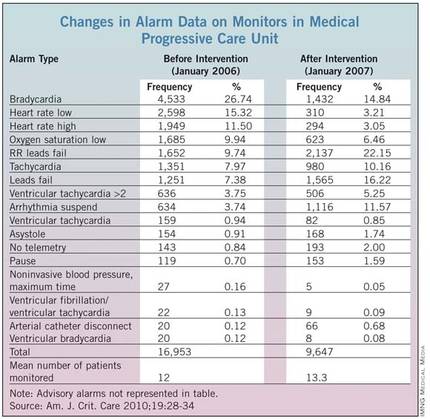

In their research paper titled "Monitor Alarm Fatigue: Standardizing Use of Physiological Monitoring and Decreasing Nuisance Alarms," Ms. Cvach and her colleague Kelly Creighton Graham, R.N., reduced alarm duplication (Am. J. Crit. Care 2010;19:28-34 [doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010651]). They describe an example:

"The alarms for high and low heart rate were the same as the bradycardia and tachycardia alarms. Although the monitor calculations differ somewhat for these events, the task force thought that the monitor alarm did not need to sound twice. Initially, as described in our paper, ... the alarms for high and low heart rate were moved to message level, and the alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were increased to warning level. Later, it was decided to alarm heart rate, and alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were messaged. The key take-away is to avoid alarm duplication while still achieving necessary patient monitoring."

Revise Alarm Default Settings

A monitor’s settings typically return to default settings each time a patient is disconnected from the monitor and a new patient is monitored. Changing default settings should not be done before careful consideration.

In an initiative undertaken at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., heart rate and oxygen saturation monitors were set to wider threshold limits and only actionable rescue events produced auditory alarm signals. This initiative resulted in early detection of patient distress, early intervention, fewer rescue events, and reduced transfers to intensive care.

In their research, Ms. Cvach and Ms. Creighton Graham were able to decrease critical monitor alarms by 43% from baseline. As they explained, one of the changes was to "revise the default settings for the unit’s monitor alarms, including parameter limits and levels, so that alarms that occurred were actionable and clinically significant."

Get "smart" about alarm monitors. Use technology to help reduce false alarms and increase recognition of clinically significant alarms.

Michael Wong is founder and executive director of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety (PPAHS). Passionate about patient safety, he was recently invited by the American Board of Physician Specialties to be a founding member of the American Board of Patient Safety. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and is on the editorial board of the Journal for Patient Compliance, a peer-reviewed journal devoted to improving patient adherence. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

When patient monitor alarms sound too many times, it can discourage using the very monitors that are intended to keep patients safe and inform clinicians of a patient’s physiological state. However, research shows that using "smart alarm" technology and getting smart about alarm monitors can reduce clinically insignificant alarms.

According to Dr. Paul M. Schyve, senior adviser for health care improvement at the Joint Commission, "There is uniform agreement that alarm fatigue is a major problem. Alarm systems are built into many medical devices, such as infusion pumps and ventilators. When they work as intended, they alert caregivers that a decision or action is required for the patient’s health and safety. However, too many alarms, including false alarms, can fatigue, confuse, and overload clinicians."

It is therefore no surprise that alarm fatigue has yet again been designated as the number one health technology hazard for 2013 by ECRI Institute, an independent, nonprofit organization that researches the best approaches to improving the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of patient care.

ECRI conducted an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration’s database of adverse events involving medical devices, and found 216 deaths nationwide from 2005 to the middle of 2010 in which problems with monitor alarms occurred. This number of deaths is thought to be low because of underreporting by the health care industry. ECRI found 13 more cases in its own database, which it compiles from incident investigations on behalf of hospital clients and from its own voluntary reporting system.

"Alarms provide a technological safety net," observed Maria Cvach, R.N., M.S.N, assistant director of nursing and clinical standards at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. "Reliance on physiological monitors to continuously ‘watch’ patients and to alert the nurse when a serious rhythm problem occurs is standard practice on monitored units. Alarms are intended to alert clinicians to deviations from a predetermined ‘normal’ status," she said.

However, alarm fatigue may occur when the sheer number of monitor alarms overwhelms caregivers. "When alarm frequency is high, nurses are at risk for becoming desensitized to the alarms that are intended to protect their patients," said Ms. Cvach.

Here are three tips to help reduce false alarms.

Use ‘Smart Alarm’ Technology

Using "smart alarm" technology that brings together a number of physiological parameters may recognize and reduce clinically insignificant alarms while accurately reflecting the patient’s condition and preserving clinically significant alarm vigilance.

"Nurses in intensive care units stated that the primary problem with alarms is that they are continuously going off, and that the largest contributor to the number of false alarms in intensive care units is the pulse oximetry alarm," said Ms. Cvach. "A ‘smart alarm’ that analyzed multiple parameters, like oxygenation and adequacy of ventilation, in a patient’s condition, may be a solution. This would increase patient safety by making it easier for nurses to assess a patient’s condition and reduce the frequency of false alarms."

Using Ms. Cvach’s example, don’t let the fear of alarms prevent you from using monitors to assess both oxygenation with pulse oximetry and the adequacy of ventilation with capnography. Using technology that incorporates multiple parameters (such as, etCO2 [end tidal CO2], SpO2, respiratory rate, and pulse rate) into a single parameter would not only make it easier to quickly identify a patient’s status, but also decrease the number of clinically insignificant alarms.

Having technology that helps rather than hinders patient care through too many false alarms would increase patient safety and improve health outcomes. Use "smart alarm" technology to decrease alarm fatigue and increase patient safety.

Reduce Alarm Duplication

In their research paper titled "Monitor Alarm Fatigue: Standardizing Use of Physiological Monitoring and Decreasing Nuisance Alarms," Ms. Cvach and her colleague Kelly Creighton Graham, R.N., reduced alarm duplication (Am. J. Crit. Care 2010;19:28-34 [doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010651]). They describe an example:

"The alarms for high and low heart rate were the same as the bradycardia and tachycardia alarms. Although the monitor calculations differ somewhat for these events, the task force thought that the monitor alarm did not need to sound twice. Initially, as described in our paper, ... the alarms for high and low heart rate were moved to message level, and the alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were increased to warning level. Later, it was decided to alarm heart rate, and alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were messaged. The key take-away is to avoid alarm duplication while still achieving necessary patient monitoring."

Revise Alarm Default Settings

A monitor’s settings typically return to default settings each time a patient is disconnected from the monitor and a new patient is monitored. Changing default settings should not be done before careful consideration.

In an initiative undertaken at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., heart rate and oxygen saturation monitors were set to wider threshold limits and only actionable rescue events produced auditory alarm signals. This initiative resulted in early detection of patient distress, early intervention, fewer rescue events, and reduced transfers to intensive care.

In their research, Ms. Cvach and Ms. Creighton Graham were able to decrease critical monitor alarms by 43% from baseline. As they explained, one of the changes was to "revise the default settings for the unit’s monitor alarms, including parameter limits and levels, so that alarms that occurred were actionable and clinically significant."

Get "smart" about alarm monitors. Use technology to help reduce false alarms and increase recognition of clinically significant alarms.

Michael Wong is founder and executive director of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety (PPAHS). Passionate about patient safety, he was recently invited by the American Board of Physician Specialties to be a founding member of the American Board of Patient Safety. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and is on the editorial board of the Journal for Patient Compliance, a peer-reviewed journal devoted to improving patient adherence. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.

When patient monitor alarms sound too many times, it can discourage using the very monitors that are intended to keep patients safe and inform clinicians of a patient’s physiological state. However, research shows that using "smart alarm" technology and getting smart about alarm monitors can reduce clinically insignificant alarms.

According to Dr. Paul M. Schyve, senior adviser for health care improvement at the Joint Commission, "There is uniform agreement that alarm fatigue is a major problem. Alarm systems are built into many medical devices, such as infusion pumps and ventilators. When they work as intended, they alert caregivers that a decision or action is required for the patient’s health and safety. However, too many alarms, including false alarms, can fatigue, confuse, and overload clinicians."

It is therefore no surprise that alarm fatigue has yet again been designated as the number one health technology hazard for 2013 by ECRI Institute, an independent, nonprofit organization that researches the best approaches to improving the safety, quality, and cost-effectiveness of patient care.

ECRI conducted an analysis of the Food and Drug Administration’s database of adverse events involving medical devices, and found 216 deaths nationwide from 2005 to the middle of 2010 in which problems with monitor alarms occurred. This number of deaths is thought to be low because of underreporting by the health care industry. ECRI found 13 more cases in its own database, which it compiles from incident investigations on behalf of hospital clients and from its own voluntary reporting system.

"Alarms provide a technological safety net," observed Maria Cvach, R.N., M.S.N, assistant director of nursing and clinical standards at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. "Reliance on physiological monitors to continuously ‘watch’ patients and to alert the nurse when a serious rhythm problem occurs is standard practice on monitored units. Alarms are intended to alert clinicians to deviations from a predetermined ‘normal’ status," she said.

However, alarm fatigue may occur when the sheer number of monitor alarms overwhelms caregivers. "When alarm frequency is high, nurses are at risk for becoming desensitized to the alarms that are intended to protect their patients," said Ms. Cvach.

Here are three tips to help reduce false alarms.

Use ‘Smart Alarm’ Technology

Using "smart alarm" technology that brings together a number of physiological parameters may recognize and reduce clinically insignificant alarms while accurately reflecting the patient’s condition and preserving clinically significant alarm vigilance.

"Nurses in intensive care units stated that the primary problem with alarms is that they are continuously going off, and that the largest contributor to the number of false alarms in intensive care units is the pulse oximetry alarm," said Ms. Cvach. "A ‘smart alarm’ that analyzed multiple parameters, like oxygenation and adequacy of ventilation, in a patient’s condition, may be a solution. This would increase patient safety by making it easier for nurses to assess a patient’s condition and reduce the frequency of false alarms."

Using Ms. Cvach’s example, don’t let the fear of alarms prevent you from using monitors to assess both oxygenation with pulse oximetry and the adequacy of ventilation with capnography. Using technology that incorporates multiple parameters (such as, etCO2 [end tidal CO2], SpO2, respiratory rate, and pulse rate) into a single parameter would not only make it easier to quickly identify a patient’s status, but also decrease the number of clinically insignificant alarms.

Having technology that helps rather than hinders patient care through too many false alarms would increase patient safety and improve health outcomes. Use "smart alarm" technology to decrease alarm fatigue and increase patient safety.

Reduce Alarm Duplication

In their research paper titled "Monitor Alarm Fatigue: Standardizing Use of Physiological Monitoring and Decreasing Nuisance Alarms," Ms. Cvach and her colleague Kelly Creighton Graham, R.N., reduced alarm duplication (Am. J. Crit. Care 2010;19:28-34 [doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010651]). They describe an example:

"The alarms for high and low heart rate were the same as the bradycardia and tachycardia alarms. Although the monitor calculations differ somewhat for these events, the task force thought that the monitor alarm did not need to sound twice. Initially, as described in our paper, ... the alarms for high and low heart rate were moved to message level, and the alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were increased to warning level. Later, it was decided to alarm heart rate, and alarms for bradycardia and tachycardia were messaged. The key take-away is to avoid alarm duplication while still achieving necessary patient monitoring."

Revise Alarm Default Settings

A monitor’s settings typically return to default settings each time a patient is disconnected from the monitor and a new patient is monitored. Changing default settings should not be done before careful consideration.

In an initiative undertaken at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H., heart rate and oxygen saturation monitors were set to wider threshold limits and only actionable rescue events produced auditory alarm signals. This initiative resulted in early detection of patient distress, early intervention, fewer rescue events, and reduced transfers to intensive care.

In their research, Ms. Cvach and Ms. Creighton Graham were able to decrease critical monitor alarms by 43% from baseline. As they explained, one of the changes was to "revise the default settings for the unit’s monitor alarms, including parameter limits and levels, so that alarms that occurred were actionable and clinically significant."

Get "smart" about alarm monitors. Use technology to help reduce false alarms and increase recognition of clinically significant alarms.

Michael Wong is founder and executive director of the Physician-Patient Alliance for Health & Safety (PPAHS). Passionate about patient safety, he was recently invited by the American Board of Physician Specialties to be a founding member of the American Board of Patient Safety. He is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and is on the editorial board of the Journal for Patient Compliance, a peer-reviewed journal devoted to improving patient adherence. The researchers reported no conflicts of interest.