User login

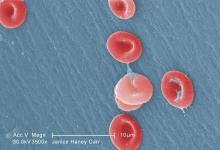

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

This study is particularly valuable because of the “depth, breadth and completeness” of data from across an entire state, a control group that is socioeconomically matched, and a study that was done during a time when new, life-saving vaccines were licensed and recommended. The many changes in the recommendations because of new vaccines and new understanding of the best use of these vaccines make for a complex schedule, but we health care providers need to keep current and to educate parents so their children are protected against infectious diseases. For parents of children with sickle cell disease, the schedule is more complex and the need is greater because of their extreme vulnerability. Wagner et al. suggest that “a proactive electronic prompt to providers [and parents] for vaccines needed for children with special conditions [as exists for the general immunization schedule] is needed – and seems doable.”

Sarah S. Long, MD, is a professor of pediatrics at Drexel University, Philadelphia. She is an associate editor of the Journal of Pediatrics and the Red Book Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases of the American Academy of Pediatrics. She reported no disclosures. This is a summary of her editorial accompanying the article by Wagner et al. (J. Pediatr. 2018;196:3).

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Substantial percentages of children with sickle cell disease are not receiving certain recommended vaccines on time or at all, found a study examining receipt of pneumococcal and meningococcal vaccines among children born in Michigan.

Although these children were more likely to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccines than others their age without sickle cell disease (SCD), nearly one-third had not received all their pneumococcal vaccines by 36 months old. These children are at higher risk of meningococcal and invasive pneumococcal disease because they lack normal spleen function.

ACIP has recommended since February 2010 that all children receive the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which replaced the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) that had been recommended since October 2000.

But ACIP also recommends that children with SCD receive two doses of the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23), starting at 2 years old. These children also should receive a PCV13 dose before age 18 years, even if they received the full PCV7 vaccine series.

“By directly including SCD status in a child’s immunization record, an immunization information system could use a specialized algorithm to indicate to healthcare providers which vaccines should be given to a patient with SCD, which may differ from a typical patient,” Dr. Wagner and his colleagues wrote in The Journal of Pediatrics.

“Educational campaigns targeted to parents of these children and their providers could also help advance the importance of vaccination, particularly as more vaccines enter the market, many of which may be highly recommended for children with SCD,” they said.

The researchers matched 1,022 children with SCD to 3,725 children without SCD based on age, sex, race, and zip code. The data was based on the Michigan Care Improvement Registry (MCIR), Michigan Vital Records live birth file, and the Michigan Newborn Screening Program for children born in the state between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

At age 36 months, 69% of children with SCD had been fully vaccinated with the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine series, compared with 45% of children without SCD. The meningococcal vaccine had been administered to 59% of children with SCD.

Children with SCD were more likely than those without the disease to be up-to-date on their pneumococcal vaccine(s) at 5, 7 and 16 months old.

Nevertheless, substantial percentages of children with SCD who received the complete series of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine had not received two other pneumococcal vaccines. Just over 29% were missing a dose of PCV13, 21.8% of children over 2 years old had not received any dose of PPV23, and 50.7% had not received a second dose of PPV23 by the age of 10 years.

The authors drew attention to the complexity of ACIP recommendations, however: ACIP released 7 recommendations a year, on average, between 2006 and 2015.

“Although providers have a responsibility to educate themselves on how best to protect children with high-risk conditions, these figures speak to the need for MCIR, the state’s immunization information system, to provide additional information on children, such as those who have sickle cell disease, who have special vaccination recommendations,” the authors wrote.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

SOURCE: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.

Key clinical point: Too few children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are receiving Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices–recommended meningococcal and pneumococcal vaccines, including PCV13 and PPSV23.

Major finding:

Study details: The findings are based on a cohort study of children with and without SCD born in Michigan between April 1, 1995, and January 1, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest. No external funding was noted.

Source: Wagner AL et al. J Pediatr. 2018 May;196:223-9.