User login

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

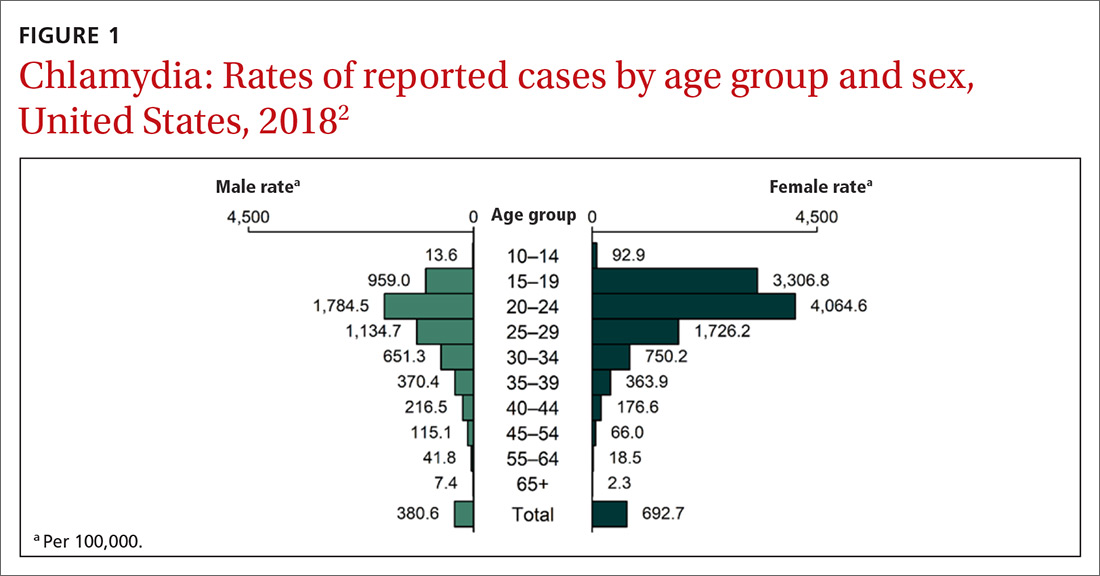

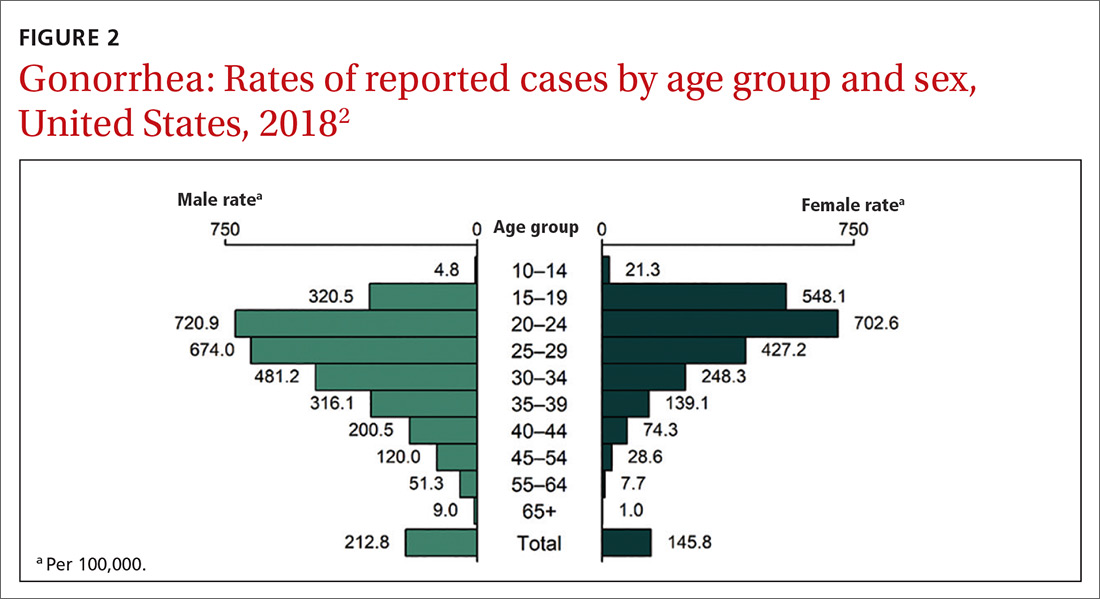

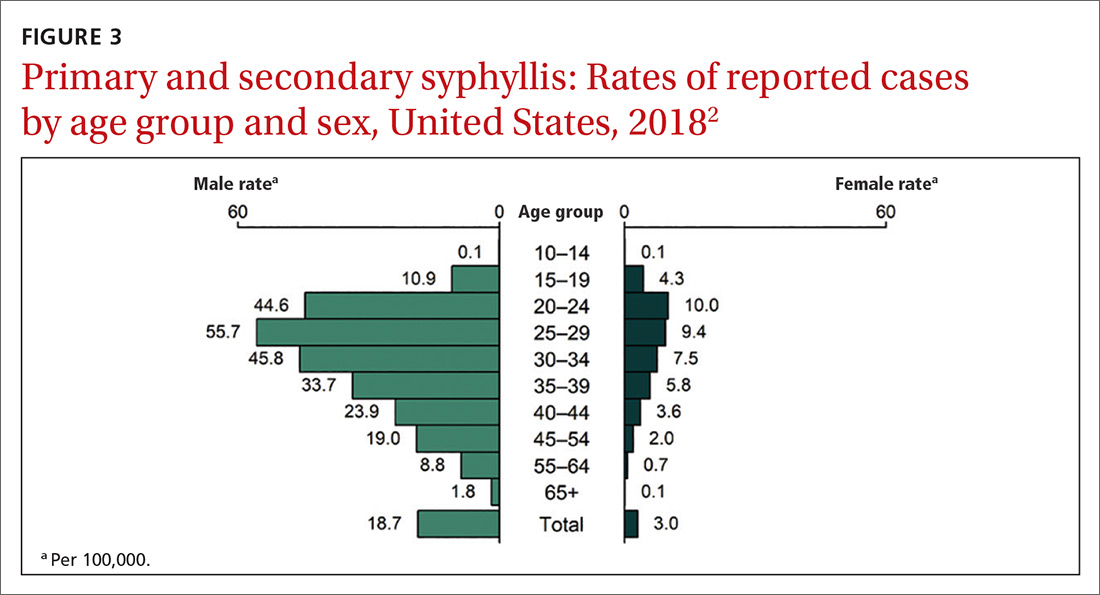

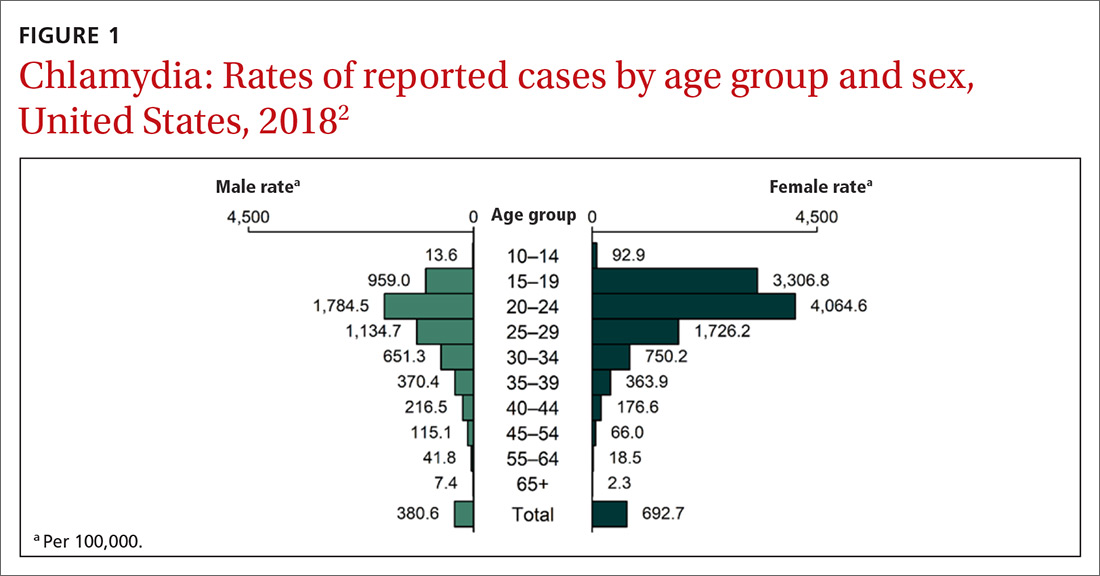

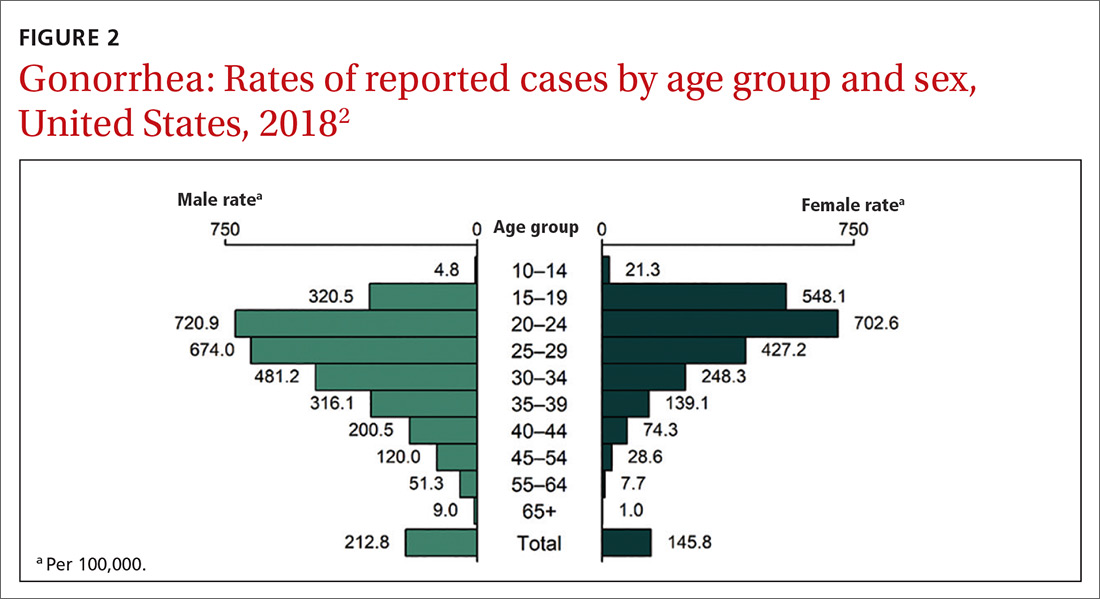

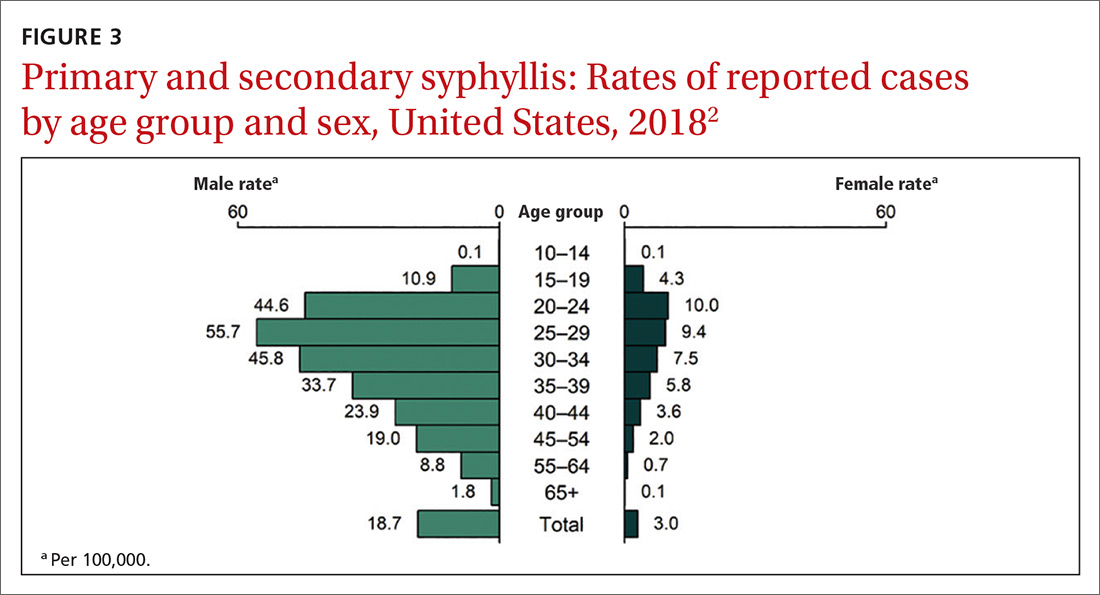

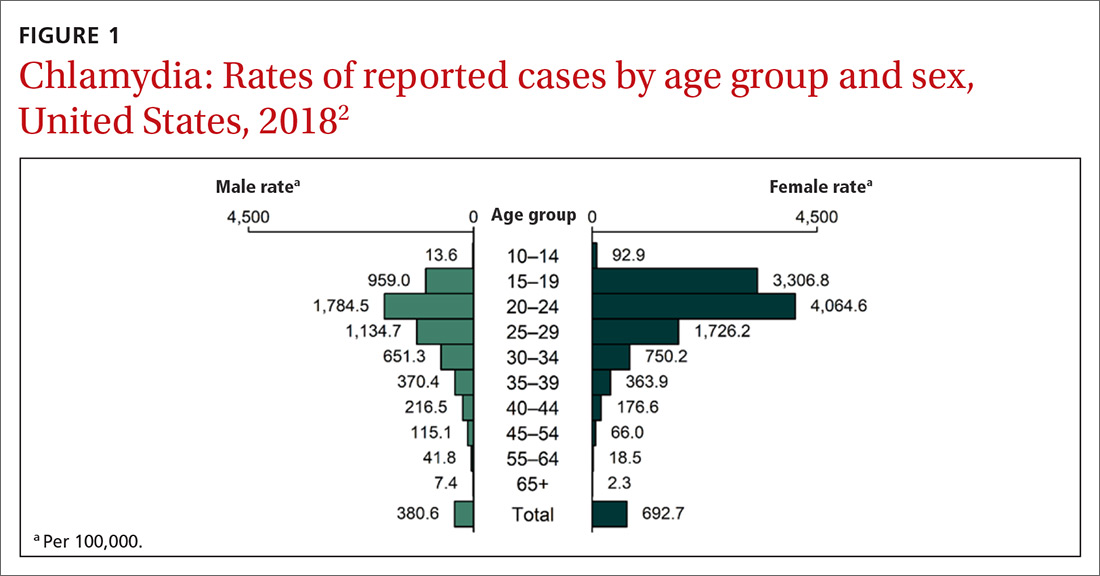

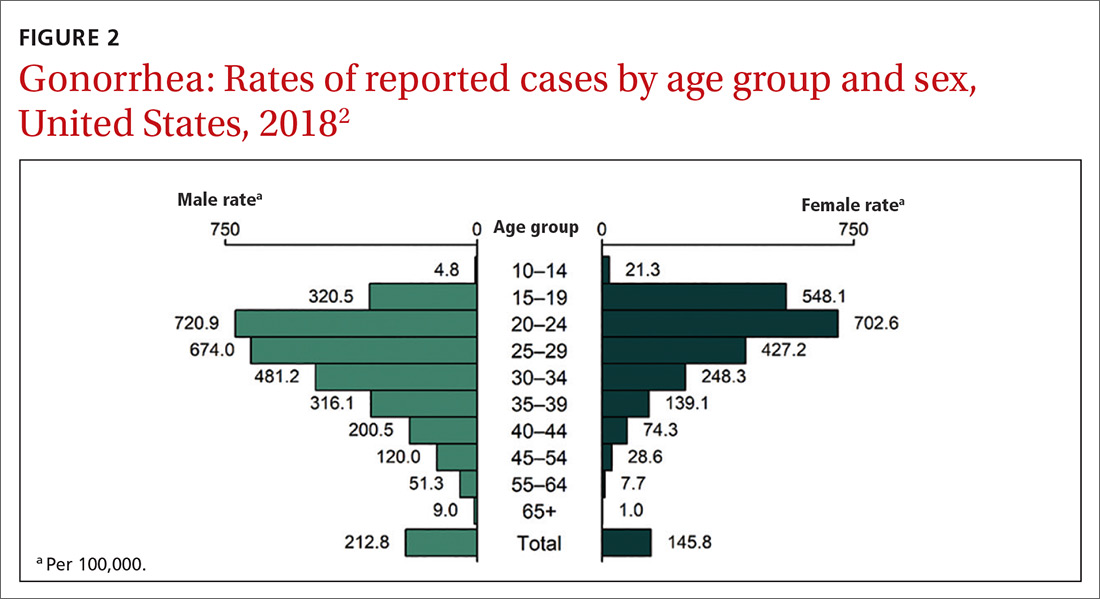

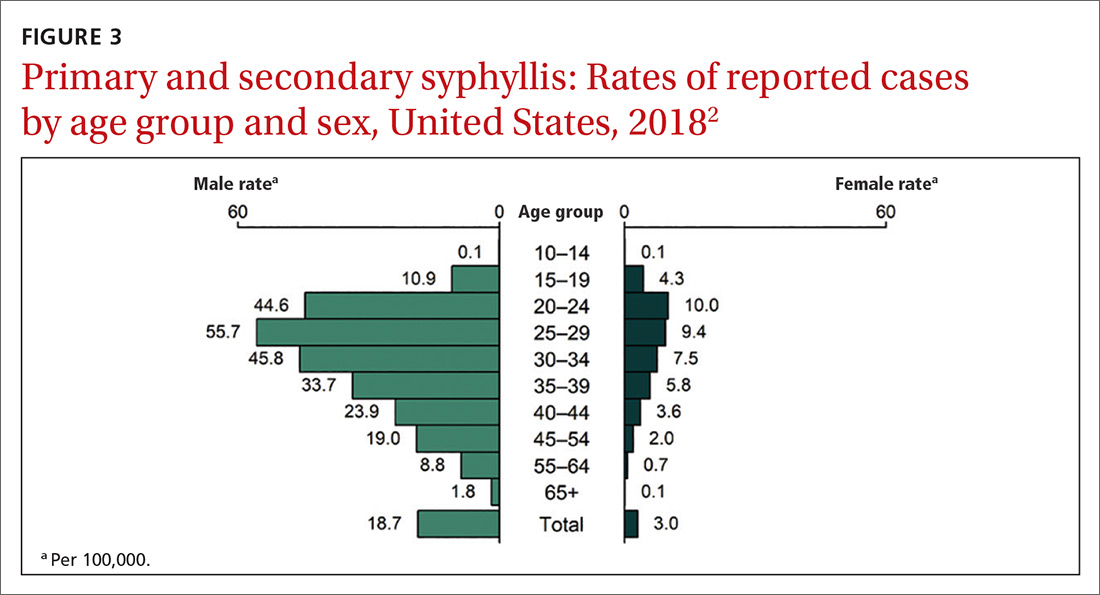

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

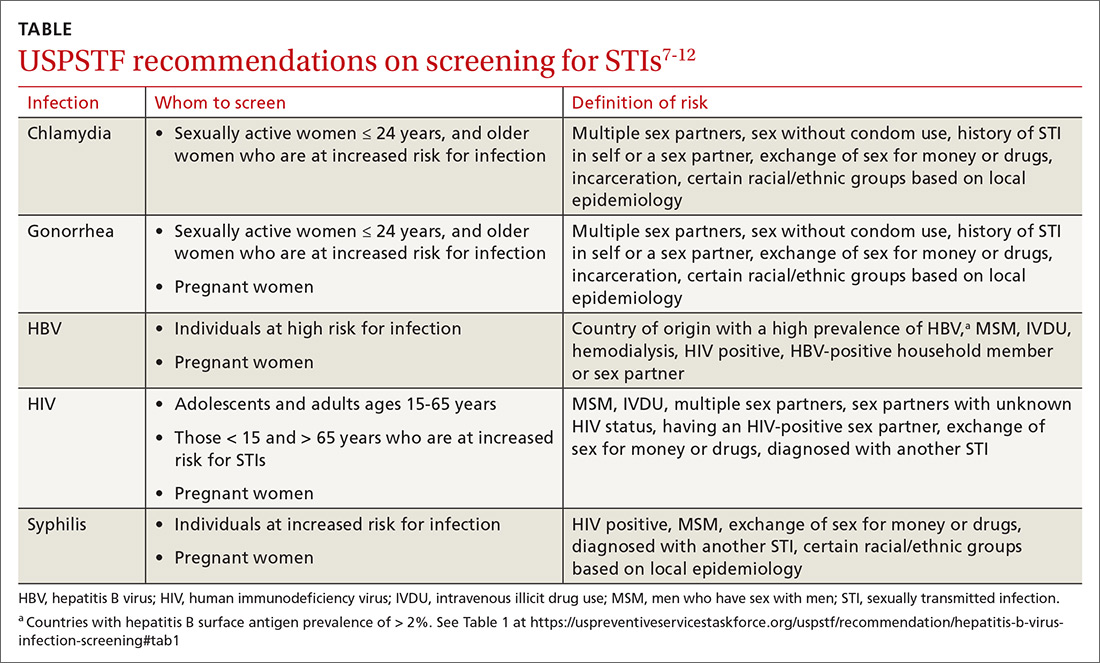

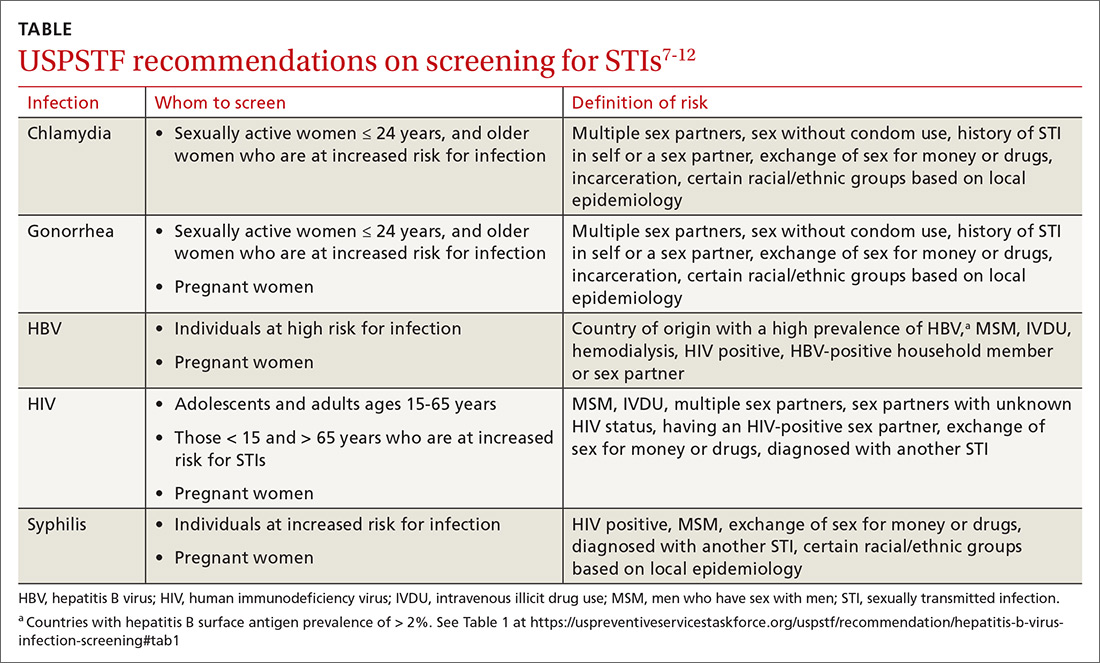

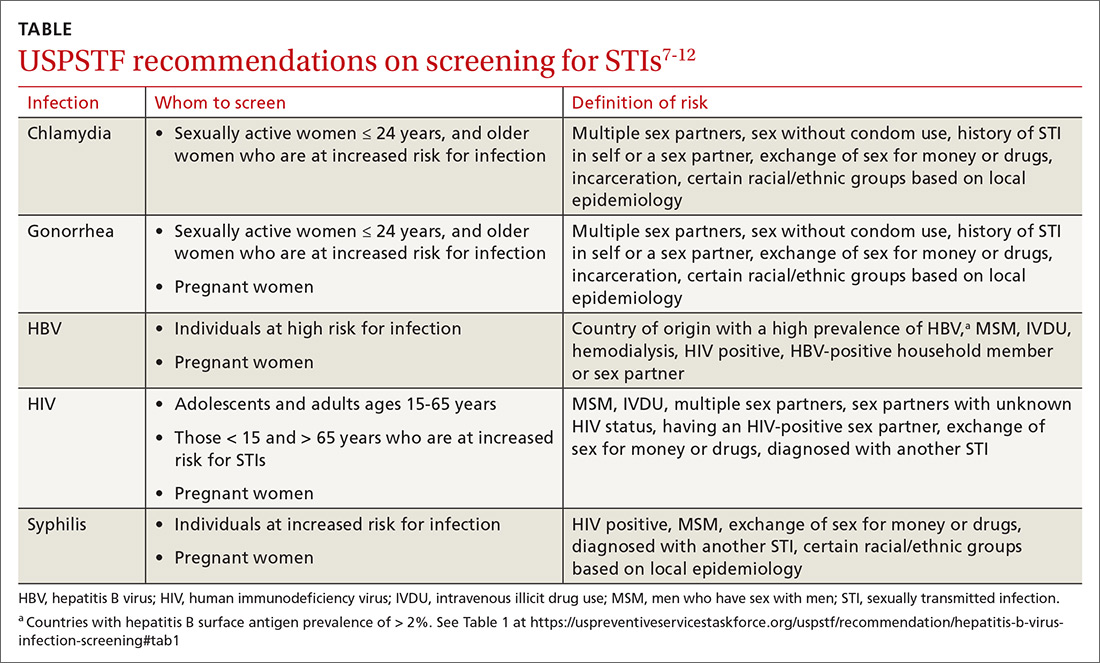

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

In August 2020, the US Preventive Services Task Force published an update of its recommendation on preventing sexually transmitted infections (STIs) with behavioral counseling interventions.1

Whom to counsel. The USPSTF continues to recommend behavioral counseling for all sexually active adolescents and for adults at increased risk for STIs. Adults at increased risk include those who have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, those with multiple sex partners or a sex partner at high risk for an STI, those not using condoms consistently, and those belonging to populations with high prevalence rates of STIs. These populations with high prevalence rates include1

- individuals seeking care at STI clinics,

- sexual and gender minorities, and

- those who are positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), use injection drugs, exchange sex for drugs or money, or have recently been in a correctional facility.

Features of effective counseling. The Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians provide behavioral counseling or refer to counseling services or suggest media-based interventions. The most effective counseling interventions are those that span more than 120 minutes over several sessions. But the Task Force also states that counseling lasting about 30 minutes in a single session can also be effective. Counseling should include information about common STIs and their modes of transmission; encouragement in the use of safer sex practices; and training in proper condom use, how to communicate with partners about safer sex practices, and problem-solving. Various approaches to this counseling can be found at https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

This updated recommendation is timely because most STIs in the United States have been increasing in incidence for the past decade or longer.2 Per 100,000 population, the total number of chlamydia cases since 2000 has risen from 251.4 to 539.9 (115%);gonorrhea cases since 2009 have risen from 98.1 to 179.1 (83%).3 And since 2000, the total number of reported syphilis cases per 100,000 has risen from 2.1 to 10.8 (414%).3

Chlamydia affects primarily those ages 15 to 24 years, with highest rates occurring in females (FIGURE 1).2 Gonorrhea affects women and men fairly evenly with slightly higher rates in men; the highest rates are seen in those ages 20 to 29 (FIGURE 2).2 Syphilis predominantly affects men who have sex with men, and the highest rates are in those ages 20 to 34 (FIGURE 3).2 In contrast to these upward trends, the number of HIV cases diagnosed has been relatively steady, with a slight downward trend over the past decade.4Other STIs that can be prevented through behavioral counseling include herpes simplex, human papillomavirus (HPV), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and trichomonas vaginalis.

Continue to: How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

How to integrate STI preventioninto the primary care encounter

A key resource for learning to recognize the signs and symptoms of STIs, to correctly diagnose them, and to treat them according to CDC guidelines can be found at www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm.5 Equally important is to integrate the prevention of STIs into the clinical routine by using a 4-step approach: risk assessment, risk reduction (counseling and chemoprevention), screening, and vaccination.

Risk assessment. The first step in prevention is taking a sexual history to accurately assess a patient’s risk for STIs. The CDC provides a tool (www.cdc.gov/std/products/provider-pocket-guides.htm) that can assist in gathering information in a nonjudgmental fashion about 5 Ps: partners, practices, protection from STIs, past history of STIs, and prevention of pregnancy.

Risk reduction. Following STI risk assessment, recommend risk-reduction interventions, as appropriate. Notable in the new Task Force recommendation are behavioral counseling methods that work. Additionally, when needed, pre-exposure prophylaxis with effective antiretroviral agents can be offered to those at high risk of HIV.6

Screening. Task Force recommendations for STI screening are described in the TABLE.7-12 Screening for HIV, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and HBV are also recommended for pregnant women. And, although pregnant women are not specifically mentioned in the recommendation on chlamydia screening, it is reasonable to include it in prenatal care testing for STIs.

The Task Force has made an “I” statement regarding screening for gonorrhea and chlamydia in males. This does not mean that screening should be avoided, but only that there is insufficient evidence to support a firm statement regarding the harms and benefits in males. Keep in mind that this applies to asymptomatic males, and that testing and preventive treatment are warranted after documented exposure to either infection.

The Task Force recommends against screening for genital herpes, including in pregnant women, because of a lack of evidence of benefit from such screening, the high rate of false-positive tests, and the potential to cause anxiety and harm to personal relationships.

Continue to: Although hepatitis C virus...

Although hepatitis C virus (HCV) is transmitted mainly through intravenous drug use, it can also be transmitted sexually. The Task Force recommends screening for HCV in all adults ages 18 to 79 years.13

Vaccination. Two STIs can be prevented by immunizations: HPV and HBV. The current recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) are to vaccinate all infants with HBV vaccine and all unvaccinated children and adolescents through age 18.14 Unvaccinated adults who are at risk for HBV infection, including those at risk through sexual practices, should also be vaccinated.14

ACIP recommends routine HPV vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, but it can be started as early as 9 years.15 Catch-up vaccination is recommended for males and females through age 26 years.15 The vaccine is approved for use in individuals ages 27 through 45 years, but ACIP has not recommended it for routine use in this age group, and has instead recommended shared clinical decision-making to evaluate whether there is potential individual benefit from the vaccine.15

Public health implications

All STIs are reportable to local or state health departments. This is important for tracking community infection trends and, if resources are available, for contact notification and testing. In most jurisdictions, local health department resources are limited and contact tracing may be restricted to syphilis and HIV infections. When this is the case, it is especially important to instruct patients in whom STIs have been detected to notify their recent sex partners and advise them to be tested or preventively treated.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT)—providing treatment for exposed sexual contacts without a clinical encounter—is allowed in some states and is a tool that can prevent re-infection in the treated patient and suppress spread in the community. This is most useful for partners of those with gonorrhea, chlamydia, or trichomonas. The CDC has published guidance on how to implement EPT in a clinical setting if state law allows it.16

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

1. Henderson JT, Senger CA, Henninger M, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections. JAMA. 2020;324:682-699.

2. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/slides.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

3. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/tables/1.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

4. CDC. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States (2010-2018). www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/slidesets/cdc-hiv-surveillance-epidemiology-2018.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

5. CDC. 2015 sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed November 25, 2020.

6. USPSTF. Prevention of human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection: pre-exposure prophylaxis. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis. Accessed November 25, 2020.

7. LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:902-910. 8. USPSTF. Syphilis infection in nonpregnant adults and adolescents: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/syphilis-infection-in-nonpregnant-adults-and-adolescents. Accessed November 25, 2020.

9. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for syphilis in pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:911-917.

10. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321:2326-2336.

11. USPSTF. US Preventive Services Task Force issues draft recommendation statement on screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/hepatitis-b-nonpregnant-adults-draft-rs-bulletin.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.

12. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Screening for Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Pregnant Women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;322:349-354.

13. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening. Accessed November 25, 2020. 14. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67;1-31.

15. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

16. CDC. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Accessed November 25, 2020.