User login

Practitioners providing care to children are familiar with the childhood immunization schedule and routinely administer varicella vaccine at the 12-month and 4- to 5-year visits. However, when is the last time most of us or any of the current trainees have seen a case?

Briefly, varicella is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV). It is characterized by a generalized pruritic erythematous rash in various stages of development beginning as macules, progressing to papules, and ultimately becoming vesicular lesions on an erythematous base (“dewdrop on a rose petal”) and resolves with crusting of the lesion (Figure 1). It has an incubation period of 10-21 days with symptoms usually developing within 14-16 days after exposure. The vesicular rash must be differentiated from enterovirus, Staphylococcus aureus, contact dermatitis, or insect bites, which initially may be difficult. Approximately 50% of children can have symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, headache, and occasionally, mild abdominal pain in the 24-48 hours prior to the appearance of rash. Lesions usually first appear on the scalp, face, or trunk in successive crops over several days. A person with varicella has lesions in various stages.

In a normal host, new vesicle formation usually stops within 4 days, and most lesions have fully crusted by day 6. VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia and may reactivate years or decades later to cause herpes zoster (HZ). Most healthy children with varicella recover without sequelae so the disease is generally regarded as benign. However, varicella can lead to serious complications and deaths in healthy as well as immunocompromised persons.

Complications of Varicella: bacterial superinfection of skin lesions most often with Streptococcus pyogenes or S aureus manifested as cellulitis, myositis, or necrotizing fasciitis; neurologic complications include cerebellar ataxia and encephalitis with the latter seen most often in adults. Pneumonia occurs most often in adults, especially those infected during pregnancy. Another concern, infection during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy can lead to fetal death or severe birth defects, including limb hypoplasia, cutaneous scarring, ocular abnormalities, and central nervous system damage (congenital varicella syndrome).

The risk for development of severe disseminated disease was first noted in the 1960s as treatments for leukemia in children improved. They were surviving their cancer only to develop severe and often fatal varicella. Today it is recognized that development of disseminated disease is a risk for all infected persons with impaired T cell function, malignancies, HIV, or receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

Reye’s syndrome is rarely seen today since taking salicylates while infected with VZV was identified as a predisposing factor for development.

VZV is only found in humans and transmission is person to person or airborne. The secondary household attack rate is approximately 90%. In contrast, the secondary attack rates in classrooms may be as low as 12%-33%. Transmission rates in the tropics for unexplained reasons are also lower.

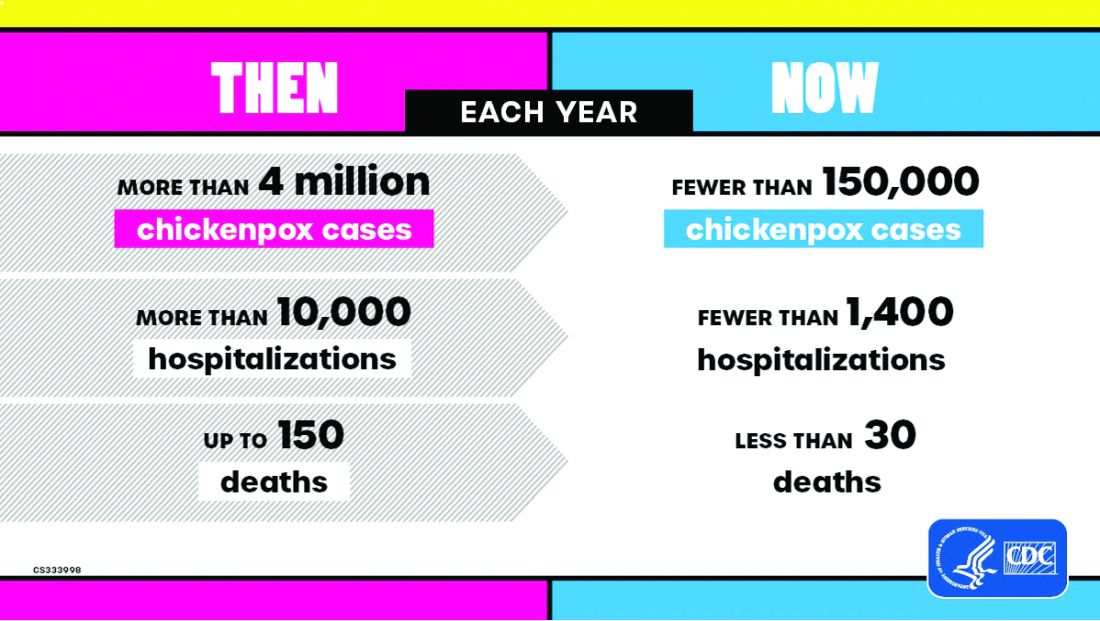

Vaccine History: Why do we rarely see this disease anymore? Varicella, a live attenuated vaccine, was developed in 1974 by Dr. Michiaki Takahashi. It remains the only vaccine directed against a herpes group virus. In 1979, the Collaborative Varicella Vaccine Study Group was established at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and additional safety and efficacy trials were conducted in the United States initially in leukemic patients in remission and later in healthy children, which supported Takahashi’s data. Licensure of varicella vaccine was granted in 1995. That same year, due to continuing disease and societal burden, the United States was the first country to incorporate varicella into the routine childhood immunization schedule, which resulted in significant reductions in cases. To further improve control of varicella, in 2007 vaccine recommendations were revised and a routine two-dose schedule was implemented. The impact of varicella disease pre- and post-vaccine licensure is illustrated in Figure 2. Not listed, is that in the pre-vaccine era, there were approximately 44 cases of congenital varicella syndrome annually.

As of 2023 only 23% (45/195) of nations routinely administer this vaccine and 4% (8/195) have restricted recommendations. The remaining 73% of countries do not offer the vaccine, including all countries on the African continent, and Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jordan, Lebanon, Philippines, Portugal, and Venezuela to list a few.

Varicella Outbreak: In October 2022, New York City (NYC) identified a varicella outbreak primarily involving persons who recently migrated from Central and South America and lived in a shelter in NYC or residential facility (n = 105); the outbreak is ongoing. As of March 8, 2024, 873 cases (53%) were among children aged 4-18 years and 91.9% had no documentation of varicella vaccine at time of symptom onset. There were 28 hospitalizations, and no deaths reported. The most common sources of transmission were the residential facilities (41.3%) and importation or possible importation (39.4%). School transmission accounted for only 1.2% of cases.

Most migrants arrived from countries where varicella vaccination is not part of the routine childhood immunization schedule. Although most cases occurred in children, almost 30% occurred in adults. Many of the migrants arrived from tropical countries where susceptibility rates are also higher in adults. This outbreak is a reminder of the importance of limiting disease transmission by maintaining high vaccination rates. To curtail this outbreak, approximately 27,000 doses of varicella vaccine were administered to the arriving migrants. In addition, MMR, COVID-19, influenza, and all routine pediatric vaccines required for school entry were administered. Temporary closure of the residential facilities were required. Education was provided to residents regarding immunizations as well as assistance to help them establish a primary care home. Multiple agencies were mobilized to successfully coordinate these efforts.

Take Home Message

1. Each country has its own routine immunization schedule. It may not include all vaccines recommended in the US schedule. When questioned I’m frequently told that immunizations are up to date, only to review records and find they are not, especially when it is related to MMR. It is often administered at 9 months and/or MR or MM is administered depending on the country. As reported here, varicella is a routine vaccine in only 45 countries.

2.

3. Once an outbreak has been identified, the infrastructure to manage and contain it must already be established. In most instances there will be a need for a rapid and often large-scale effort involving multiple agencies including local health care providers.

4. Not all diseases are reportable. Only deaths by varicella are nationally notifiable. Otherwise, cases are reported voluntarily. As of November 2, 2024, there have been 5,157 cases of varicella reported, excluding any cases from NYC.

Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

CDC. Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases and Conditions, United States: Weekly Tables. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/nndss_weekly_tables_menu.asp.

Graham KA et al. Varicella Outbreak Among Recent Arrivals to New York City, 2022-2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 May 30;73(21):478-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7321a1.

Marin M et al. Health and Economic Impact of the United States Varicella Vaccination Program, 1996-2020. J Infect Dis. 2022 Oct 21;226(Suppl 4):S463-S469. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac271.

Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections in Kimberkin DW et al, eds. Red Book: 2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 33rd Edition. American Academy of Pediatrics, 2024:938-951. https://www.aap.org/Red-Book-2024-Report-of-the-Committee-on-Infectious-Diseases-33rd-Edition-Paperback?srsltid=AfmBOoqyF60rR9ZwQ5jA8AouNhtRRTyPLnc_r7HWw7JVYV8v33Hr2vQS.

Practitioners providing care to children are familiar with the childhood immunization schedule and routinely administer varicella vaccine at the 12-month and 4- to 5-year visits. However, when is the last time most of us or any of the current trainees have seen a case?

Briefly, varicella is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV). It is characterized by a generalized pruritic erythematous rash in various stages of development beginning as macules, progressing to papules, and ultimately becoming vesicular lesions on an erythematous base (“dewdrop on a rose petal”) and resolves with crusting of the lesion (Figure 1). It has an incubation period of 10-21 days with symptoms usually developing within 14-16 days after exposure. The vesicular rash must be differentiated from enterovirus, Staphylococcus aureus, contact dermatitis, or insect bites, which initially may be difficult. Approximately 50% of children can have symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, headache, and occasionally, mild abdominal pain in the 24-48 hours prior to the appearance of rash. Lesions usually first appear on the scalp, face, or trunk in successive crops over several days. A person with varicella has lesions in various stages.

In a normal host, new vesicle formation usually stops within 4 days, and most lesions have fully crusted by day 6. VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia and may reactivate years or decades later to cause herpes zoster (HZ). Most healthy children with varicella recover without sequelae so the disease is generally regarded as benign. However, varicella can lead to serious complications and deaths in healthy as well as immunocompromised persons.

Complications of Varicella: bacterial superinfection of skin lesions most often with Streptococcus pyogenes or S aureus manifested as cellulitis, myositis, or necrotizing fasciitis; neurologic complications include cerebellar ataxia and encephalitis with the latter seen most often in adults. Pneumonia occurs most often in adults, especially those infected during pregnancy. Another concern, infection during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy can lead to fetal death or severe birth defects, including limb hypoplasia, cutaneous scarring, ocular abnormalities, and central nervous system damage (congenital varicella syndrome).

The risk for development of severe disseminated disease was first noted in the 1960s as treatments for leukemia in children improved. They were surviving their cancer only to develop severe and often fatal varicella. Today it is recognized that development of disseminated disease is a risk for all infected persons with impaired T cell function, malignancies, HIV, or receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

Reye’s syndrome is rarely seen today since taking salicylates while infected with VZV was identified as a predisposing factor for development.

VZV is only found in humans and transmission is person to person or airborne. The secondary household attack rate is approximately 90%. In contrast, the secondary attack rates in classrooms may be as low as 12%-33%. Transmission rates in the tropics for unexplained reasons are also lower.

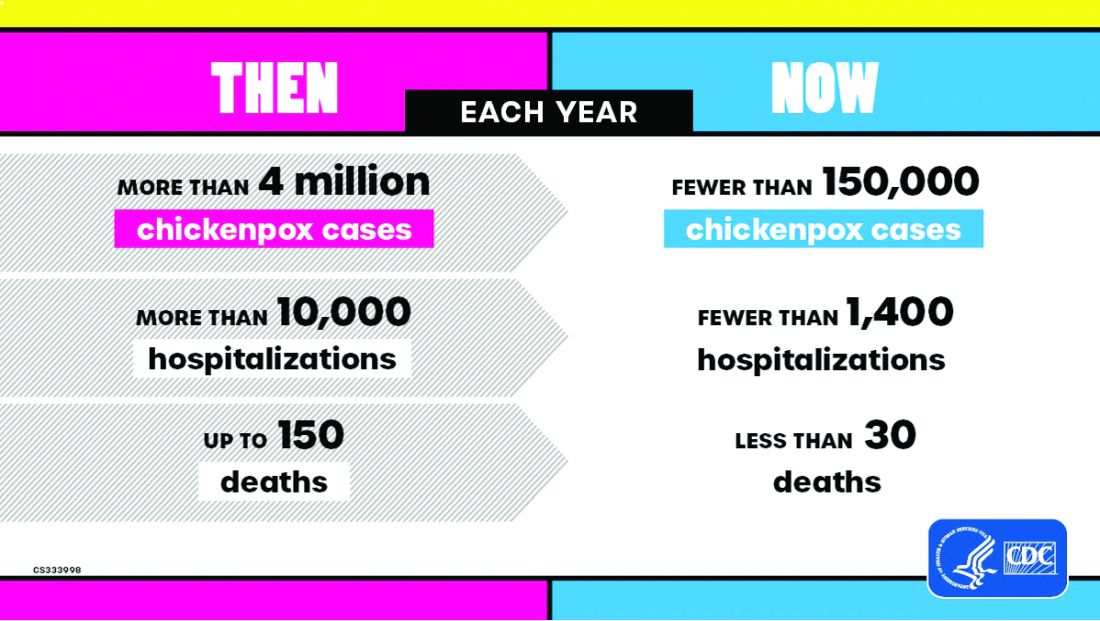

Vaccine History: Why do we rarely see this disease anymore? Varicella, a live attenuated vaccine, was developed in 1974 by Dr. Michiaki Takahashi. It remains the only vaccine directed against a herpes group virus. In 1979, the Collaborative Varicella Vaccine Study Group was established at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and additional safety and efficacy trials were conducted in the United States initially in leukemic patients in remission and later in healthy children, which supported Takahashi’s data. Licensure of varicella vaccine was granted in 1995. That same year, due to continuing disease and societal burden, the United States was the first country to incorporate varicella into the routine childhood immunization schedule, which resulted in significant reductions in cases. To further improve control of varicella, in 2007 vaccine recommendations were revised and a routine two-dose schedule was implemented. The impact of varicella disease pre- and post-vaccine licensure is illustrated in Figure 2. Not listed, is that in the pre-vaccine era, there were approximately 44 cases of congenital varicella syndrome annually.

As of 2023 only 23% (45/195) of nations routinely administer this vaccine and 4% (8/195) have restricted recommendations. The remaining 73% of countries do not offer the vaccine, including all countries on the African continent, and Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jordan, Lebanon, Philippines, Portugal, and Venezuela to list a few.

Varicella Outbreak: In October 2022, New York City (NYC) identified a varicella outbreak primarily involving persons who recently migrated from Central and South America and lived in a shelter in NYC or residential facility (n = 105); the outbreak is ongoing. As of March 8, 2024, 873 cases (53%) were among children aged 4-18 years and 91.9% had no documentation of varicella vaccine at time of symptom onset. There were 28 hospitalizations, and no deaths reported. The most common sources of transmission were the residential facilities (41.3%) and importation or possible importation (39.4%). School transmission accounted for only 1.2% of cases.

Most migrants arrived from countries where varicella vaccination is not part of the routine childhood immunization schedule. Although most cases occurred in children, almost 30% occurred in adults. Many of the migrants arrived from tropical countries where susceptibility rates are also higher in adults. This outbreak is a reminder of the importance of limiting disease transmission by maintaining high vaccination rates. To curtail this outbreak, approximately 27,000 doses of varicella vaccine were administered to the arriving migrants. In addition, MMR, COVID-19, influenza, and all routine pediatric vaccines required for school entry were administered. Temporary closure of the residential facilities were required. Education was provided to residents regarding immunizations as well as assistance to help them establish a primary care home. Multiple agencies were mobilized to successfully coordinate these efforts.

Take Home Message

1. Each country has its own routine immunization schedule. It may not include all vaccines recommended in the US schedule. When questioned I’m frequently told that immunizations are up to date, only to review records and find they are not, especially when it is related to MMR. It is often administered at 9 months and/or MR or MM is administered depending on the country. As reported here, varicella is a routine vaccine in only 45 countries.

2.

3. Once an outbreak has been identified, the infrastructure to manage and contain it must already be established. In most instances there will be a need for a rapid and often large-scale effort involving multiple agencies including local health care providers.

4. Not all diseases are reportable. Only deaths by varicella are nationally notifiable. Otherwise, cases are reported voluntarily. As of November 2, 2024, there have been 5,157 cases of varicella reported, excluding any cases from NYC.

Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

CDC. Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases and Conditions, United States: Weekly Tables. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/nndss_weekly_tables_menu.asp.

Graham KA et al. Varicella Outbreak Among Recent Arrivals to New York City, 2022-2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 May 30;73(21):478-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7321a1.

Marin M et al. Health and Economic Impact of the United States Varicella Vaccination Program, 1996-2020. J Infect Dis. 2022 Oct 21;226(Suppl 4):S463-S469. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac271.

Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections in Kimberkin DW et al, eds. Red Book: 2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 33rd Edition. American Academy of Pediatrics, 2024:938-951. https://www.aap.org/Red-Book-2024-Report-of-the-Committee-on-Infectious-Diseases-33rd-Edition-Paperback?srsltid=AfmBOoqyF60rR9ZwQ5jA8AouNhtRRTyPLnc_r7HWw7JVYV8v33Hr2vQS.

Practitioners providing care to children are familiar with the childhood immunization schedule and routinely administer varicella vaccine at the 12-month and 4- to 5-year visits. However, when is the last time most of us or any of the current trainees have seen a case?

Briefly, varicella is a highly contagious disease caused by varicella-zoster virus (VZV). It is characterized by a generalized pruritic erythematous rash in various stages of development beginning as macules, progressing to papules, and ultimately becoming vesicular lesions on an erythematous base (“dewdrop on a rose petal”) and resolves with crusting of the lesion (Figure 1). It has an incubation period of 10-21 days with symptoms usually developing within 14-16 days after exposure. The vesicular rash must be differentiated from enterovirus, Staphylococcus aureus, contact dermatitis, or insect bites, which initially may be difficult. Approximately 50% of children can have symptoms including fever, malaise, anorexia, headache, and occasionally, mild abdominal pain in the 24-48 hours prior to the appearance of rash. Lesions usually first appear on the scalp, face, or trunk in successive crops over several days. A person with varicella has lesions in various stages.

In a normal host, new vesicle formation usually stops within 4 days, and most lesions have fully crusted by day 6. VZV establishes latency in sensory ganglia and may reactivate years or decades later to cause herpes zoster (HZ). Most healthy children with varicella recover without sequelae so the disease is generally regarded as benign. However, varicella can lead to serious complications and deaths in healthy as well as immunocompromised persons.

Complications of Varicella: bacterial superinfection of skin lesions most often with Streptococcus pyogenes or S aureus manifested as cellulitis, myositis, or necrotizing fasciitis; neurologic complications include cerebellar ataxia and encephalitis with the latter seen most often in adults. Pneumonia occurs most often in adults, especially those infected during pregnancy. Another concern, infection during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy can lead to fetal death or severe birth defects, including limb hypoplasia, cutaneous scarring, ocular abnormalities, and central nervous system damage (congenital varicella syndrome).

The risk for development of severe disseminated disease was first noted in the 1960s as treatments for leukemia in children improved. They were surviving their cancer only to develop severe and often fatal varicella. Today it is recognized that development of disseminated disease is a risk for all infected persons with impaired T cell function, malignancies, HIV, or receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

Reye’s syndrome is rarely seen today since taking salicylates while infected with VZV was identified as a predisposing factor for development.

VZV is only found in humans and transmission is person to person or airborne. The secondary household attack rate is approximately 90%. In contrast, the secondary attack rates in classrooms may be as low as 12%-33%. Transmission rates in the tropics for unexplained reasons are also lower.

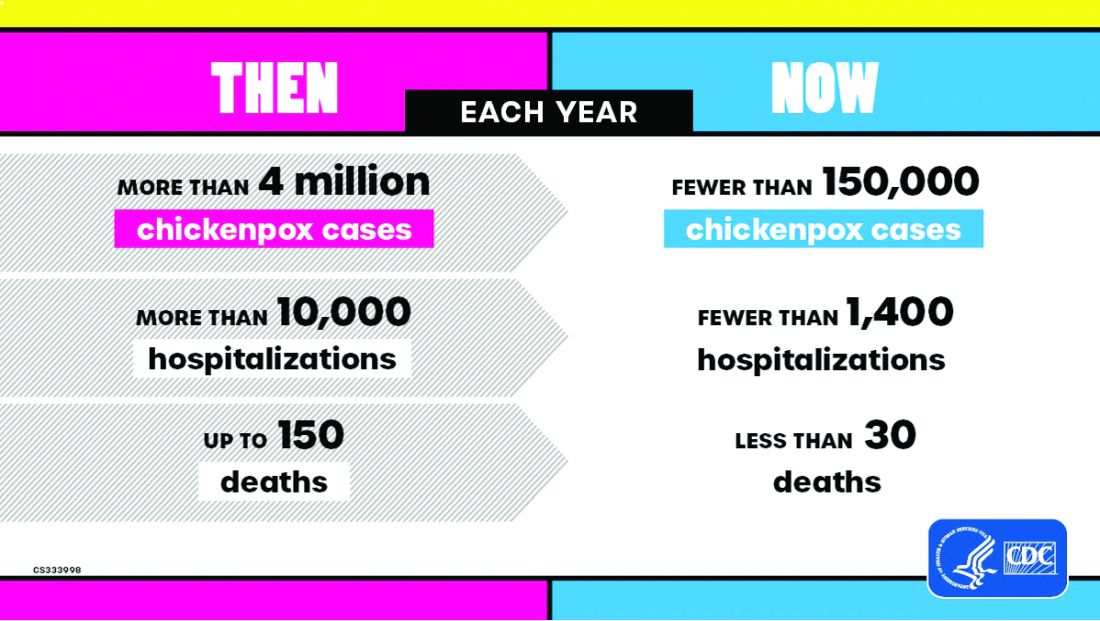

Vaccine History: Why do we rarely see this disease anymore? Varicella, a live attenuated vaccine, was developed in 1974 by Dr. Michiaki Takahashi. It remains the only vaccine directed against a herpes group virus. In 1979, the Collaborative Varicella Vaccine Study Group was established at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and additional safety and efficacy trials were conducted in the United States initially in leukemic patients in remission and later in healthy children, which supported Takahashi’s data. Licensure of varicella vaccine was granted in 1995. That same year, due to continuing disease and societal burden, the United States was the first country to incorporate varicella into the routine childhood immunization schedule, which resulted in significant reductions in cases. To further improve control of varicella, in 2007 vaccine recommendations were revised and a routine two-dose schedule was implemented. The impact of varicella disease pre- and post-vaccine licensure is illustrated in Figure 2. Not listed, is that in the pre-vaccine era, there were approximately 44 cases of congenital varicella syndrome annually.

As of 2023 only 23% (45/195) of nations routinely administer this vaccine and 4% (8/195) have restricted recommendations. The remaining 73% of countries do not offer the vaccine, including all countries on the African continent, and Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Jordan, Lebanon, Philippines, Portugal, and Venezuela to list a few.

Varicella Outbreak: In October 2022, New York City (NYC) identified a varicella outbreak primarily involving persons who recently migrated from Central and South America and lived in a shelter in NYC or residential facility (n = 105); the outbreak is ongoing. As of March 8, 2024, 873 cases (53%) were among children aged 4-18 years and 91.9% had no documentation of varicella vaccine at time of symptom onset. There were 28 hospitalizations, and no deaths reported. The most common sources of transmission were the residential facilities (41.3%) and importation or possible importation (39.4%). School transmission accounted for only 1.2% of cases.

Most migrants arrived from countries where varicella vaccination is not part of the routine childhood immunization schedule. Although most cases occurred in children, almost 30% occurred in adults. Many of the migrants arrived from tropical countries where susceptibility rates are also higher in adults. This outbreak is a reminder of the importance of limiting disease transmission by maintaining high vaccination rates. To curtail this outbreak, approximately 27,000 doses of varicella vaccine were administered to the arriving migrants. In addition, MMR, COVID-19, influenza, and all routine pediatric vaccines required for school entry were administered. Temporary closure of the residential facilities were required. Education was provided to residents regarding immunizations as well as assistance to help them establish a primary care home. Multiple agencies were mobilized to successfully coordinate these efforts.

Take Home Message

1. Each country has its own routine immunization schedule. It may not include all vaccines recommended in the US schedule. When questioned I’m frequently told that immunizations are up to date, only to review records and find they are not, especially when it is related to MMR. It is often administered at 9 months and/or MR or MM is administered depending on the country. As reported here, varicella is a routine vaccine in only 45 countries.

2.

3. Once an outbreak has been identified, the infrastructure to manage and contain it must already be established. In most instances there will be a need for a rapid and often large-scale effort involving multiple agencies including local health care providers.

4. Not all diseases are reportable. Only deaths by varicella are nationally notifiable. Otherwise, cases are reported voluntarily. As of November 2, 2024, there have been 5,157 cases of varicella reported, excluding any cases from NYC.

Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Suggested Reading

CDC. Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases and Conditions, United States: Weekly Tables. https://wonder.cdc.gov/nndss/nndss_weekly_tables_menu.asp.

Graham KA et al. Varicella Outbreak Among Recent Arrivals to New York City, 2022-2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 May 30;73(21):478-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7321a1.

Marin M et al. Health and Economic Impact of the United States Varicella Vaccination Program, 1996-2020. J Infect Dis. 2022 Oct 21;226(Suppl 4):S463-S469. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac271.

Varicella-Zoster Virus Infections in Kimberkin DW et al, eds. Red Book: 2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 33rd Edition. American Academy of Pediatrics, 2024:938-951. https://www.aap.org/Red-Book-2024-Report-of-the-Committee-on-Infectious-Diseases-33rd-Edition-Paperback?srsltid=AfmBOoqyF60rR9ZwQ5jA8AouNhtRRTyPLnc_r7HWw7JVYV8v33Hr2vQS.