User login

In a pilot study of five patients with ventricular tachycardia (VT) storm that was refractory to antiarrhythmic drug therapy, treatment with noninvasive transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TCMS) was associated with a lower arrhythmia burden.

The five patients were men aged 40 to 68 years with VT storm, defined as at least three episodes of sustained VT in the preceding 24 hours. The patients experienced a drop in both sustained and nonsustained VT with TCMS.

The study “aimed at developing a novel system for noninvasively and nondestructively interrupting the sympathetic tone,” corresponding author Timothy M. Markman, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. “We demonstrated that the technique was safe and that there was a strong signal of efficacy,” he added.

“We know that interrupting the sympathetic tone in these patients is beneficial,” said Markman, “but our strategies for doing so are mostly invasive and associated with a significant risk profile.”

The research letter was published online May 5 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It was also presented during the virtual Heart Rhythm Society 2020 conference.

Growing body of evidence

Numerous studies have linked autonomic neuromodulation, including local blockade of the left stellate ganglion, with a reduction of cardiac sympathetic input in patients with VT storm, the authors write.

“This adds to a growing body of literature that autonomic neuromodulation is a valuable tool in the management of arrhythmias,” said Markman.

The use of magnetic stimulation to treat arrhythmias by targeting cardiac sympathetic innervation has been demonstrated in animal studies. The authors note that, to their knowledge, this is the first study involving humans.

Evidence suggests that TCMS may serve as a bridge for patients with difficult-to- treat VT to reduce VT and eliminate antiarrhythmic drug therapies and the associated risks, the authors say.

A lower VT burden

Five participants were included in the study. The patients were followed from March 2019 to June 2019. All had experienced at least three episodes of sustained VT (>30 sec) in the 24 hours preceding treatment. Patients with implantable cardiac devices were excluded.

The investigators used a figure 8 TCMS coil that was attached to a magnetic stimulation system positioned lateral to the C7 spinous process in approximation of the left stellate ganglion. TCMS was delivered at 80% of the left trapezius motor threshold at a frequency of 0.9 Hz for 60 minutes, the authors write. For one patient (patient no. 4), TCMS was shut off after 17 minutes, owing to the coil’s overheating. That resulted in the patient’s not being able to complete the protocol, they note.

Patients were monitored during and immediately after treatment for adverse events, including hemodynamic compromise, local discomfort, and skin irritation.

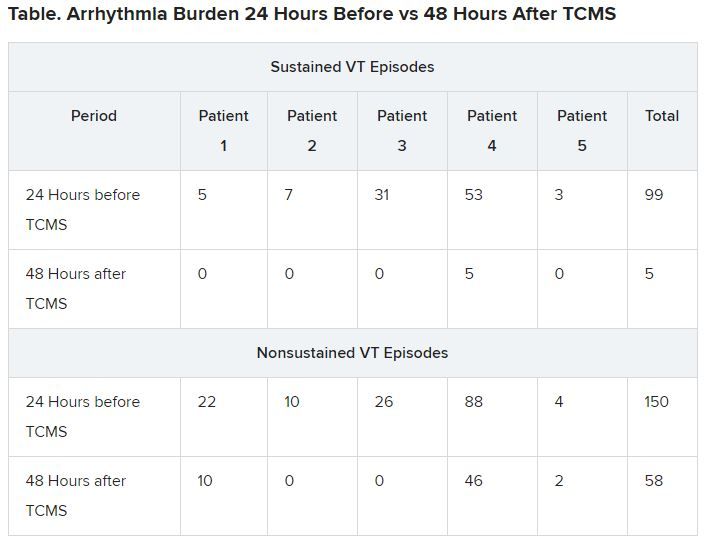

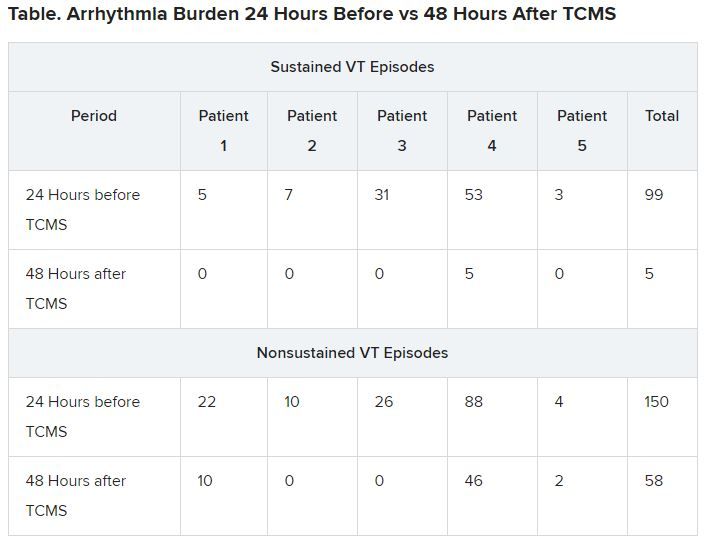

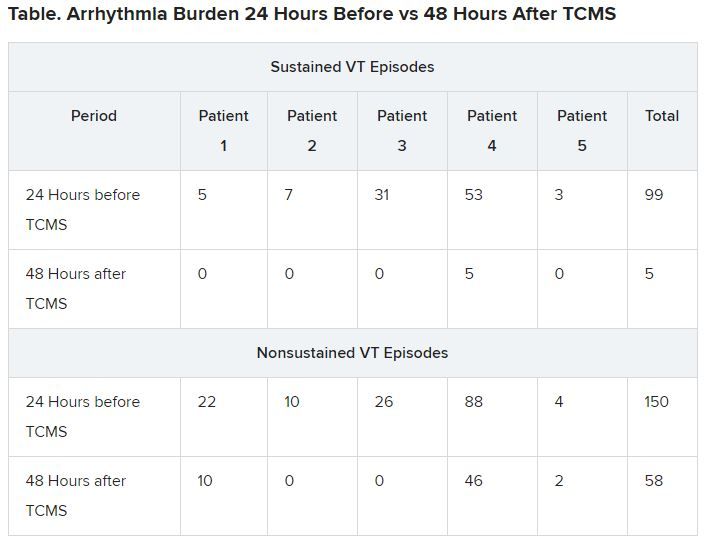

Results showed that compared to the 24-hour baseline period, sustained VT was reduced from 99 to five episodes, and nonsustained VT was reduced from 150 to 58 episodes in the 48 hours following TCMS.

In addition, 41 total external shocks were performed at the 24-hour baseline before TCMS. No external shocks were performed 48 hours after TCMS treatment.

Of the three patients who were not under sedation, none reported discomfort from TCMS.

Before TCMS treatment began, VT was refractory to a mean (SD) of 2.5 (2.1) antiarrhythmic drugs per patient. Within the 48-hour follow-up, patients received a mean of 1.2 (0.7) antiarrhythmic drugs. No additional antiarrhythmic drug was added, the authors note. Only patient no. 4, who did not complete the protocol, underwent ablation 36 hours post enrollment, they add.

The authors note some limitations, such as small case number. Markman told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that enrollment of patients in a randomized, sham-controlled trial to demonstrate efficacy is underway.

Physiology studies to evaluate the effects of this therapy while optimizing the technical aspects of the delivery of transcutaneous magnetic stimulation are also being conducted, he adds. Other limitations include the absence of control measures and exclusion of patients with implantable cardiac devices.

A potential addition to treatment

Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, past president of the American Heart Association and current dean of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, who was not involved in the research, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that “the results are kind of interesting; it actually changes the function in the ganglion in the neck that actually innervates the heart, excites the heart, if you will.

“Clearly it wasn’t something that was just happening while this therapy was applied, but instead there’s some changes made when the sympathetic ganglion is targeted,” Tomaselli said. “They’re changing it functionally somehow, reducing the stimulating input to the heart, and in doing so, reducing the frequency of arrhythmias.”

Tomaselli suggested TCMS might be helpful in choosing among alternative treatments, such as sympathetic denervation. “It might also be a way to decide whether or not somebody might benefit, for example, from permanent dissection,” he said. “If you do this therapy, if it quiets things down but then it comes back after a while, you may consider denervation of that ganglion.”

Tomaselli adds that this treatment might be applied in different ways. “In some future iteration, it could even be implantable, could be patient activated or automatically activated ― for example, if a rapid heart rate is detected, that kind of thing.”

He noted that “there may be applications of this ultra-low frequency to other arrythmias, more common arrythmias, less life-threatening arrythmias, like atrial fibrillation; so there are a number of ways you might consider using this to treat cardiac rhythm disturbances by targeting the nervous system.”

Nazarian has consulted for Siemens, CardioSolv, and Circle Software and is a principle investigator for research funding to the University of Pennsylvania from Biosense-Webster, Siemens, ImriCor, and the National Institutes of Health. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study of five patients with ventricular tachycardia (VT) storm that was refractory to antiarrhythmic drug therapy, treatment with noninvasive transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TCMS) was associated with a lower arrhythmia burden.

The five patients were men aged 40 to 68 years with VT storm, defined as at least three episodes of sustained VT in the preceding 24 hours. The patients experienced a drop in both sustained and nonsustained VT with TCMS.

The study “aimed at developing a novel system for noninvasively and nondestructively interrupting the sympathetic tone,” corresponding author Timothy M. Markman, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. “We demonstrated that the technique was safe and that there was a strong signal of efficacy,” he added.

“We know that interrupting the sympathetic tone in these patients is beneficial,” said Markman, “but our strategies for doing so are mostly invasive and associated with a significant risk profile.”

The research letter was published online May 5 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It was also presented during the virtual Heart Rhythm Society 2020 conference.

Growing body of evidence

Numerous studies have linked autonomic neuromodulation, including local blockade of the left stellate ganglion, with a reduction of cardiac sympathetic input in patients with VT storm, the authors write.

“This adds to a growing body of literature that autonomic neuromodulation is a valuable tool in the management of arrhythmias,” said Markman.

The use of magnetic stimulation to treat arrhythmias by targeting cardiac sympathetic innervation has been demonstrated in animal studies. The authors note that, to their knowledge, this is the first study involving humans.

Evidence suggests that TCMS may serve as a bridge for patients with difficult-to- treat VT to reduce VT and eliminate antiarrhythmic drug therapies and the associated risks, the authors say.

A lower VT burden

Five participants were included in the study. The patients were followed from March 2019 to June 2019. All had experienced at least three episodes of sustained VT (>30 sec) in the 24 hours preceding treatment. Patients with implantable cardiac devices were excluded.

The investigators used a figure 8 TCMS coil that was attached to a magnetic stimulation system positioned lateral to the C7 spinous process in approximation of the left stellate ganglion. TCMS was delivered at 80% of the left trapezius motor threshold at a frequency of 0.9 Hz for 60 minutes, the authors write. For one patient (patient no. 4), TCMS was shut off after 17 minutes, owing to the coil’s overheating. That resulted in the patient’s not being able to complete the protocol, they note.

Patients were monitored during and immediately after treatment for adverse events, including hemodynamic compromise, local discomfort, and skin irritation.

Results showed that compared to the 24-hour baseline period, sustained VT was reduced from 99 to five episodes, and nonsustained VT was reduced from 150 to 58 episodes in the 48 hours following TCMS.

In addition, 41 total external shocks were performed at the 24-hour baseline before TCMS. No external shocks were performed 48 hours after TCMS treatment.

Of the three patients who were not under sedation, none reported discomfort from TCMS.

Before TCMS treatment began, VT was refractory to a mean (SD) of 2.5 (2.1) antiarrhythmic drugs per patient. Within the 48-hour follow-up, patients received a mean of 1.2 (0.7) antiarrhythmic drugs. No additional antiarrhythmic drug was added, the authors note. Only patient no. 4, who did not complete the protocol, underwent ablation 36 hours post enrollment, they add.

The authors note some limitations, such as small case number. Markman told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that enrollment of patients in a randomized, sham-controlled trial to demonstrate efficacy is underway.

Physiology studies to evaluate the effects of this therapy while optimizing the technical aspects of the delivery of transcutaneous magnetic stimulation are also being conducted, he adds. Other limitations include the absence of control measures and exclusion of patients with implantable cardiac devices.

A potential addition to treatment

Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, past president of the American Heart Association and current dean of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, who was not involved in the research, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that “the results are kind of interesting; it actually changes the function in the ganglion in the neck that actually innervates the heart, excites the heart, if you will.

“Clearly it wasn’t something that was just happening while this therapy was applied, but instead there’s some changes made when the sympathetic ganglion is targeted,” Tomaselli said. “They’re changing it functionally somehow, reducing the stimulating input to the heart, and in doing so, reducing the frequency of arrhythmias.”

Tomaselli suggested TCMS might be helpful in choosing among alternative treatments, such as sympathetic denervation. “It might also be a way to decide whether or not somebody might benefit, for example, from permanent dissection,” he said. “If you do this therapy, if it quiets things down but then it comes back after a while, you may consider denervation of that ganglion.”

Tomaselli adds that this treatment might be applied in different ways. “In some future iteration, it could even be implantable, could be patient activated or automatically activated ― for example, if a rapid heart rate is detected, that kind of thing.”

He noted that “there may be applications of this ultra-low frequency to other arrythmias, more common arrythmias, less life-threatening arrythmias, like atrial fibrillation; so there are a number of ways you might consider using this to treat cardiac rhythm disturbances by targeting the nervous system.”

Nazarian has consulted for Siemens, CardioSolv, and Circle Software and is a principle investigator for research funding to the University of Pennsylvania from Biosense-Webster, Siemens, ImriCor, and the National Institutes of Health. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a pilot study of five patients with ventricular tachycardia (VT) storm that was refractory to antiarrhythmic drug therapy, treatment with noninvasive transcutaneous magnetic stimulation (TCMS) was associated with a lower arrhythmia burden.

The five patients were men aged 40 to 68 years with VT storm, defined as at least three episodes of sustained VT in the preceding 24 hours. The patients experienced a drop in both sustained and nonsustained VT with TCMS.

The study “aimed at developing a novel system for noninvasively and nondestructively interrupting the sympathetic tone,” corresponding author Timothy M. Markman, MD, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. “We demonstrated that the technique was safe and that there was a strong signal of efficacy,” he added.

“We know that interrupting the sympathetic tone in these patients is beneficial,” said Markman, “but our strategies for doing so are mostly invasive and associated with a significant risk profile.”

The research letter was published online May 5 in the Journal of the American Medical Association. It was also presented during the virtual Heart Rhythm Society 2020 conference.

Growing body of evidence

Numerous studies have linked autonomic neuromodulation, including local blockade of the left stellate ganglion, with a reduction of cardiac sympathetic input in patients with VT storm, the authors write.

“This adds to a growing body of literature that autonomic neuromodulation is a valuable tool in the management of arrhythmias,” said Markman.

The use of magnetic stimulation to treat arrhythmias by targeting cardiac sympathetic innervation has been demonstrated in animal studies. The authors note that, to their knowledge, this is the first study involving humans.

Evidence suggests that TCMS may serve as a bridge for patients with difficult-to- treat VT to reduce VT and eliminate antiarrhythmic drug therapies and the associated risks, the authors say.

A lower VT burden

Five participants were included in the study. The patients were followed from March 2019 to June 2019. All had experienced at least three episodes of sustained VT (>30 sec) in the 24 hours preceding treatment. Patients with implantable cardiac devices were excluded.

The investigators used a figure 8 TCMS coil that was attached to a magnetic stimulation system positioned lateral to the C7 spinous process in approximation of the left stellate ganglion. TCMS was delivered at 80% of the left trapezius motor threshold at a frequency of 0.9 Hz for 60 minutes, the authors write. For one patient (patient no. 4), TCMS was shut off after 17 minutes, owing to the coil’s overheating. That resulted in the patient’s not being able to complete the protocol, they note.

Patients were monitored during and immediately after treatment for adverse events, including hemodynamic compromise, local discomfort, and skin irritation.

Results showed that compared to the 24-hour baseline period, sustained VT was reduced from 99 to five episodes, and nonsustained VT was reduced from 150 to 58 episodes in the 48 hours following TCMS.

In addition, 41 total external shocks were performed at the 24-hour baseline before TCMS. No external shocks were performed 48 hours after TCMS treatment.

Of the three patients who were not under sedation, none reported discomfort from TCMS.

Before TCMS treatment began, VT was refractory to a mean (SD) of 2.5 (2.1) antiarrhythmic drugs per patient. Within the 48-hour follow-up, patients received a mean of 1.2 (0.7) antiarrhythmic drugs. No additional antiarrhythmic drug was added, the authors note. Only patient no. 4, who did not complete the protocol, underwent ablation 36 hours post enrollment, they add.

The authors note some limitations, such as small case number. Markman told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that enrollment of patients in a randomized, sham-controlled trial to demonstrate efficacy is underway.

Physiology studies to evaluate the effects of this therapy while optimizing the technical aspects of the delivery of transcutaneous magnetic stimulation are also being conducted, he adds. Other limitations include the absence of control measures and exclusion of patients with implantable cardiac devices.

A potential addition to treatment

Gordon F. Tomaselli, MD, past president of the American Heart Association and current dean of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, who was not involved in the research, told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that “the results are kind of interesting; it actually changes the function in the ganglion in the neck that actually innervates the heart, excites the heart, if you will.

“Clearly it wasn’t something that was just happening while this therapy was applied, but instead there’s some changes made when the sympathetic ganglion is targeted,” Tomaselli said. “They’re changing it functionally somehow, reducing the stimulating input to the heart, and in doing so, reducing the frequency of arrhythmias.”

Tomaselli suggested TCMS might be helpful in choosing among alternative treatments, such as sympathetic denervation. “It might also be a way to decide whether or not somebody might benefit, for example, from permanent dissection,” he said. “If you do this therapy, if it quiets things down but then it comes back after a while, you may consider denervation of that ganglion.”

Tomaselli adds that this treatment might be applied in different ways. “In some future iteration, it could even be implantable, could be patient activated or automatically activated ― for example, if a rapid heart rate is detected, that kind of thing.”

He noted that “there may be applications of this ultra-low frequency to other arrythmias, more common arrythmias, less life-threatening arrythmias, like atrial fibrillation; so there are a number of ways you might consider using this to treat cardiac rhythm disturbances by targeting the nervous system.”

Nazarian has consulted for Siemens, CardioSolv, and Circle Software and is a principle investigator for research funding to the University of Pennsylvania from Biosense-Webster, Siemens, ImriCor, and the National Institutes of Health. No other relevant financial relationships have been disclosed.

This story first appeared on Medscape.com.