User login

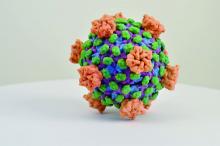

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

A viral infection may be the culprit behind celiac disease, which is caused by an autoimmune response to dietary gluten. The findings are based on an engineered reovirus, which is normally benign. The researchers believe that a reovirus may disrupt intestinal immune homeostasis in susceptible individuals as a result of infection during childhood.

According to in vitro and mouse studies carried out by the researchers, one strain of reovirus suppresses peripheral regulatory T-cell conversion and promotes T helper 1 immune response at sites that normally induce tolerance to dietary antigens. The work appeared in the April issue of Science (2017;356:44-50).

The researchers decided to investigate reoviruses. They often infect humans, commonly in early childhood when gluten usually is first introduced. They also infect humans and mice similarly, allowing a more straightforward comparison between human and mouse studies than would be possible in other virus types.

The researchers created an engineered virus made from two reovirus strains, T1L and T3D, which naturally reassort in human hosts. T1L infects the intestine, while T3D does not. The new strain, T3D-RV, retains most of the characteristics of T3D but can also infect the intestine.

The researchers then conducted mouse studies and showed that both T1L and T3D-RV affect immune responses to dietary antigens at the inductive and effector sites of oral tolerance. However, the original T1L strain caused more changes in gene transcription, both in the number of genes and the intensity of transcription level. This suggested that T1L might uniquely alter immunogenic responses to dietary antigens.

A further test in mice showed that T1L also prompted a proinflammatory response in dendritic cells that take up ovalbumin, but T3D-RV did not. Furthermore, T1L interfered with induction of peripheral tolerance to oral ovalbumin, and T3D-RV did not.

With this data in hand, the researchers turned to human subjects. They compared 73 healthy controls to 160 patients with celiac disease who were on a gluten-free diet. Celiac disease patients had higher mean antireovirus antibody titers, though the result fell short of statistical significance (P = .06), and subjects with celiac disease were over-represented among subjects who had antireovirus titers above the median value.

“You can have two viruses of the same family infecting the intestine in the same way, inducing protective immunity, and being cleared, but only one sets the stage for disease. Finally, using these two viruses allows [us] to dissociate protective immunity from immunopathology. Only the virus that has the capacity to enter the site where dietary proteins are seen by the immune system can trigger disease,” said Bana Jabri, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago.

Reovirus is unlikely to be the only, otherwise harmless, virus that could prompt wayward immune responses. The research points the way to the identification of viruses linked to celiac disease and other autoimmune diseases and could inform vaccine strategies to prevent such conditions.

The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.

FROM SCIENCE

Key clinical point: Celiac disease patients have high reovirus antibody titers.

Major finding: Researchers detail mechanistic pathway that could explain a viral link.

Data source: In vitro, human, and mouse observational studies.

Disclosures: The study received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Chicago. No conflict of interest information was disclosed in the article.