User login

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

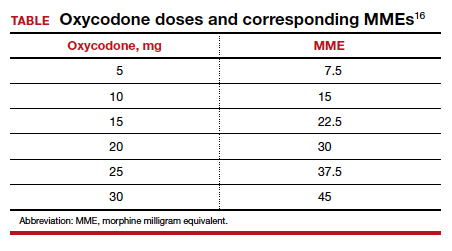

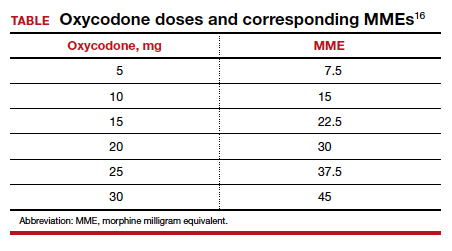

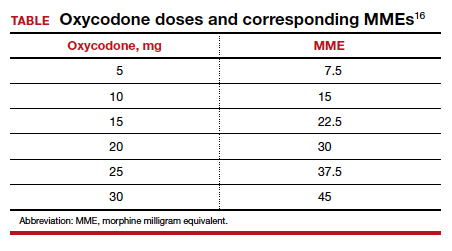

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.