User login

Case

A 66-year-old woman with metastatic, non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and hypertension presents with progressive shortness of breath and back pain. Her vital signs are normal, with the exception of tachypnea and an oxygen saturation of 84% on room air. A CT scan shows marked progression of her disease and new metastases to her spine. You begin a discussion about advance directives and code status. During the exchange, the patient asks for guidance regarding resuscitation. How can you best answer her questions about the likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest?

Background

Discussion regarding resuscitation status is a challenge for most hospitalists. The absence of an established relationship, limited time, patient emotion, and difficulty applying general scientific data to a single patient coalesce into a complex interaction. Further complicating matters, patients frequently have unrealistic expectations and overestimate their chance of survival.

Experience has shown that many patients pursue what physicians consider inappropriately aggressive resuscitation measures. Before you have an informed discussion about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes, patients tend to overestimate their likelihood of survival.1 In 2009, Kaldjian and colleagues found that patients’ initial mean prediction of post-arrest survival was 60.4%, compared with the actual mean of approximately 17%.2,3 Furthermore, nearly half of the patients who initially expressed a desire to receive CPR in the event of cardiac arrest opted to change their code status after they were informed of the actual survival estimates.1,2

Patient autonomy and the law, as defined by the 1990 Patient Self-Determination Act, require that physicians share responsibility with patients in making prospective resuscitation decisions.4 Shared decision-making necessitates a basic discussion on admission within the context of the patient’s prognosis and previously expressed wishes. It might simply include an acknowledgment of a previously completed advance directive. A more complex discussion might require in-depth conversation to address patient performance status, prognosis of acute and chronic illnesses, and education about the typical resuscitation procedures. After listening to the patient’s perspective, the admitting physician can provide input and an interpretation of available data regarding the patient’s likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest.

Review of the Data

In the past 40 years, the overall survival rates for cardiac arrest have changed little. Despite numerous advances made in the delivery of medical care, on average, only 17% of all adult arrest patients survive to hospital discharge.3 A variety of factors influence this overall survival rate, both pre-arrest and intra-arrest. Clinical experience allows most physicians to sense what probability a patient has for survival and quality of life following a cardiac arrest. However, anecdotal evidence alone does not provide a patient and their family with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding code status.

Numerous studies have investigated the patient factors that might influence how likely one is to survive a cardiac arrest. Researchers have paid particular attention to such factors as age, race, presence or absence of a cancer diagnosis, and associated comorbidities. Not surprisingly, older age has been shown to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of survival to discharge following cardiac arrest.5,6

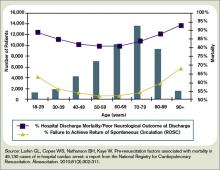

Ehlenbach and colleagues examined medical data from 433,985 Medicare patients 65 and older who underwent in-hospital CPR.5 Both older age and prior residence in a skilled nursing facility were found to be associated with poorer survival rates.5 Although neither study was able to define an upper-age cutoff for certain peri-arrest mortality, age affects overall survival likelihood in an inverse fashion, with those 85 and older having only a 6% chance of surviving to hospital discharge (see Figure 1, p. 18).1,5,6

The degree of comorbid illness can be used to help predict mortality following cardiac arrest. Review of data from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) identified particular comorbidities that portend poor post-arrest prognosis.6 In general, the more pre-existing comorbidities a patient has, the less likely they are to survive.6 The presence of hepatic insufficiency, acute stroke, immunodeficiency, renal failure, or dialysis were associated with lower survival rates (see Figure 2, right).6,7

Poor performance status on admission, defined as severe disability, coma, or vegetative state, was predictive of worse outcomes.6 Understandably, patients with hypotension and those who required vasopressors or mechanical ventilation also tended to have lower post-arrest survival rates.6

The presence of a cancer diagnosis is another prognostic factor of interest when considering the chances of surviving an arrest. Classically, CPR was thought to be a futile intervention in this patient population. Specific characteristics within this subset of patients have been shown to influence prognosis, and multiple studies have confirmed that cancer patients generally do worse after an arrest with an overall survival rate of only 6.2%.8 Survival rates tend to be lower in patients with metastatic disease, hematologic malignancies, a history of stem cell transplant, those who arrest within an ICU, and inpatients whose cardiac arrest was anticipated.8,9

In fact, cancer patients whose hospital course followed a path of gradual deterioration showed a 0% survival rate.9 In patients with metastatic disease, poor performance status prior to arrest appeared to account for their particularly poor survival odds (this supports the intuitive, rule-of-thumb that sicker cancer patients have worse outcomes).8

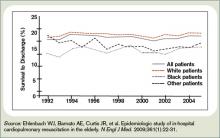

Growing evidence suggests the probability of post-arrest survival is not equal between racial groups. Specifically, black or nonwhite race is associated with higher utilization of CPR and lower survival rates (see Figure 3, right).10 Among Medicare patients, Ehlenbach and colleagues found that black and nonwhite patients were much more likely to undergo CPR, presumably as a result of being less likely to opt for DNR status.5,10 Although this could account for the differences seen in survival rates among these populations, these findings also raise concerns about the possibility of racial disparities in medical care. A subsequent cohort study also suggested that blacks and nonwhites were less likely to survive following cardiac arrest.10 However, adjusted analysis revealed that these differences were strongly associated with the medical center at which these patients received care. Therefore, although being nonwhite does portend worse outcomes following an arrest, the increased risk is likely attributed to the fact that many of these patients receive care at hospitals that have poorer overall CPR performance measures.5,10

Survival is not the only outcome measure patients need to take into account when deciding whether to undergo CPR. Quality of life following resuscitation also warrants consideration. Interestingly, research has shown that neurologic outcomes among the majority of cardiac arrest survivors are generally good.3

Approximately 86% of survivors with intact pre-arrest cerebral performance maintain it on discharge, and only a minority of survivors are eventually declared brain-dead.3 Still, there are certain peri-arrest factors that pose risk for poorer neurologic and functional outcomes. For arrest from a shockable rhythm, time to defibrillation is a key determinant.11 In patients for whom time to defibrillation is greater than two minutes, there is significantly higher risk of permanent disability following cardiac arrest.11

In the event of coma following resuscitation, particular clinical findings can be used to accurately predict poor outcome.12 The absence of pupillary reflexes, corneal reflexes, or absent or extensor motor responses three days after arrest are poor prognostic indicators.12 As a general rule, if a patient does not awaken within three days, neurologic and functional impairment can be expected.12 For those patients who do survive to hospital discharge, more than 50% ultimately will be able to be discharged home.3

However, nearly a quarter will need to be newly placed in a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility.3

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted with hypoxia secondary to both progressive lung malignancy and COPD exacerbation. She had no advanced directives, so the admitting hospitalist, in collaboration with her oncologist, had a detailed discussion regarding her understanding of her disease progression, prognosis, and goals for her remaining time. Her questions regarding survivability of cardiac arrest were answered directly with an estimate of 5% to 10%, based on her age, comorbidities, and the presence of advanced malignancy.

After hearing this information, the patient responded, “I still want everything done.” The hospitalist acknowledged her feelings of wanting to fight on, but asked her to think about what “everything” meant to her. After taking some additional time to reflect with friends and family, the patient was clear that she wanted to continue disease-focused therapies, but did not want to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac or pulmonary arrest.

Eventually, her hypoxia improved with antibiotics, steroids, and bronchodilators. She was discharged home with follow-up in the oncology clinic for additional chemotherapy and palliative radiation.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults, the average survival rate to discharge after cardiac arrest is about 17%. Many factors lower a patient’s chance of survival, including advanced age, performance status, malignancy, and presence of multiple comorbidities. TH

Dr. Neagle and Dr. Wachsberg are hospitalists and instructors in the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Medical Center in Chicago.

References

- Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santali S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545-549.

- Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):338-342.

- Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297-308.

- La Puma J, Orentlicher D, Moss RJ. Advance directives on admission. Clinical implications and analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. JAMA. 1991;266(3):402-405.

- Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22-31.

- Larkin GL, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Kaye W. Pre-resuscitation factors associated with mortality in 49,130 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the National Registry for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(3):302-311.

- de Vos R, Koster RW, De Haan RJ, Oosting H, van der Wouw PA, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers AJ. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: prearrest morbidity and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):845-850.

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, Webb FJ, Alvarez ER, Wilson GR. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2006;71(2):152-160.

- Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ, Feeley TW. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1905-1912.

- Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1195-1201.

- Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

- Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, Bassetti CL, Wiebe S. Practice parameter: prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67(2):203-210.

Case

A 66-year-old woman with metastatic, non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and hypertension presents with progressive shortness of breath and back pain. Her vital signs are normal, with the exception of tachypnea and an oxygen saturation of 84% on room air. A CT scan shows marked progression of her disease and new metastases to her spine. You begin a discussion about advance directives and code status. During the exchange, the patient asks for guidance regarding resuscitation. How can you best answer her questions about the likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest?

Background

Discussion regarding resuscitation status is a challenge for most hospitalists. The absence of an established relationship, limited time, patient emotion, and difficulty applying general scientific data to a single patient coalesce into a complex interaction. Further complicating matters, patients frequently have unrealistic expectations and overestimate their chance of survival.

Experience has shown that many patients pursue what physicians consider inappropriately aggressive resuscitation measures. Before you have an informed discussion about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes, patients tend to overestimate their likelihood of survival.1 In 2009, Kaldjian and colleagues found that patients’ initial mean prediction of post-arrest survival was 60.4%, compared with the actual mean of approximately 17%.2,3 Furthermore, nearly half of the patients who initially expressed a desire to receive CPR in the event of cardiac arrest opted to change their code status after they were informed of the actual survival estimates.1,2

Patient autonomy and the law, as defined by the 1990 Patient Self-Determination Act, require that physicians share responsibility with patients in making prospective resuscitation decisions.4 Shared decision-making necessitates a basic discussion on admission within the context of the patient’s prognosis and previously expressed wishes. It might simply include an acknowledgment of a previously completed advance directive. A more complex discussion might require in-depth conversation to address patient performance status, prognosis of acute and chronic illnesses, and education about the typical resuscitation procedures. After listening to the patient’s perspective, the admitting physician can provide input and an interpretation of available data regarding the patient’s likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest.

Review of the Data

In the past 40 years, the overall survival rates for cardiac arrest have changed little. Despite numerous advances made in the delivery of medical care, on average, only 17% of all adult arrest patients survive to hospital discharge.3 A variety of factors influence this overall survival rate, both pre-arrest and intra-arrest. Clinical experience allows most physicians to sense what probability a patient has for survival and quality of life following a cardiac arrest. However, anecdotal evidence alone does not provide a patient and their family with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding code status.

Numerous studies have investigated the patient factors that might influence how likely one is to survive a cardiac arrest. Researchers have paid particular attention to such factors as age, race, presence or absence of a cancer diagnosis, and associated comorbidities. Not surprisingly, older age has been shown to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of survival to discharge following cardiac arrest.5,6

Ehlenbach and colleagues examined medical data from 433,985 Medicare patients 65 and older who underwent in-hospital CPR.5 Both older age and prior residence in a skilled nursing facility were found to be associated with poorer survival rates.5 Although neither study was able to define an upper-age cutoff for certain peri-arrest mortality, age affects overall survival likelihood in an inverse fashion, with those 85 and older having only a 6% chance of surviving to hospital discharge (see Figure 1, p. 18).1,5,6

The degree of comorbid illness can be used to help predict mortality following cardiac arrest. Review of data from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) identified particular comorbidities that portend poor post-arrest prognosis.6 In general, the more pre-existing comorbidities a patient has, the less likely they are to survive.6 The presence of hepatic insufficiency, acute stroke, immunodeficiency, renal failure, or dialysis were associated with lower survival rates (see Figure 2, right).6,7

Poor performance status on admission, defined as severe disability, coma, or vegetative state, was predictive of worse outcomes.6 Understandably, patients with hypotension and those who required vasopressors or mechanical ventilation also tended to have lower post-arrest survival rates.6

The presence of a cancer diagnosis is another prognostic factor of interest when considering the chances of surviving an arrest. Classically, CPR was thought to be a futile intervention in this patient population. Specific characteristics within this subset of patients have been shown to influence prognosis, and multiple studies have confirmed that cancer patients generally do worse after an arrest with an overall survival rate of only 6.2%.8 Survival rates tend to be lower in patients with metastatic disease, hematologic malignancies, a history of stem cell transplant, those who arrest within an ICU, and inpatients whose cardiac arrest was anticipated.8,9

In fact, cancer patients whose hospital course followed a path of gradual deterioration showed a 0% survival rate.9 In patients with metastatic disease, poor performance status prior to arrest appeared to account for their particularly poor survival odds (this supports the intuitive, rule-of-thumb that sicker cancer patients have worse outcomes).8

Growing evidence suggests the probability of post-arrest survival is not equal between racial groups. Specifically, black or nonwhite race is associated with higher utilization of CPR and lower survival rates (see Figure 3, right).10 Among Medicare patients, Ehlenbach and colleagues found that black and nonwhite patients were much more likely to undergo CPR, presumably as a result of being less likely to opt for DNR status.5,10 Although this could account for the differences seen in survival rates among these populations, these findings also raise concerns about the possibility of racial disparities in medical care. A subsequent cohort study also suggested that blacks and nonwhites were less likely to survive following cardiac arrest.10 However, adjusted analysis revealed that these differences were strongly associated with the medical center at which these patients received care. Therefore, although being nonwhite does portend worse outcomes following an arrest, the increased risk is likely attributed to the fact that many of these patients receive care at hospitals that have poorer overall CPR performance measures.5,10

Survival is not the only outcome measure patients need to take into account when deciding whether to undergo CPR. Quality of life following resuscitation also warrants consideration. Interestingly, research has shown that neurologic outcomes among the majority of cardiac arrest survivors are generally good.3

Approximately 86% of survivors with intact pre-arrest cerebral performance maintain it on discharge, and only a minority of survivors are eventually declared brain-dead.3 Still, there are certain peri-arrest factors that pose risk for poorer neurologic and functional outcomes. For arrest from a shockable rhythm, time to defibrillation is a key determinant.11 In patients for whom time to defibrillation is greater than two minutes, there is significantly higher risk of permanent disability following cardiac arrest.11

In the event of coma following resuscitation, particular clinical findings can be used to accurately predict poor outcome.12 The absence of pupillary reflexes, corneal reflexes, or absent or extensor motor responses three days after arrest are poor prognostic indicators.12 As a general rule, if a patient does not awaken within three days, neurologic and functional impairment can be expected.12 For those patients who do survive to hospital discharge, more than 50% ultimately will be able to be discharged home.3

However, nearly a quarter will need to be newly placed in a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility.3

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted with hypoxia secondary to both progressive lung malignancy and COPD exacerbation. She had no advanced directives, so the admitting hospitalist, in collaboration with her oncologist, had a detailed discussion regarding her understanding of her disease progression, prognosis, and goals for her remaining time. Her questions regarding survivability of cardiac arrest were answered directly with an estimate of 5% to 10%, based on her age, comorbidities, and the presence of advanced malignancy.

After hearing this information, the patient responded, “I still want everything done.” The hospitalist acknowledged her feelings of wanting to fight on, but asked her to think about what “everything” meant to her. After taking some additional time to reflect with friends and family, the patient was clear that she wanted to continue disease-focused therapies, but did not want to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac or pulmonary arrest.

Eventually, her hypoxia improved with antibiotics, steroids, and bronchodilators. She was discharged home with follow-up in the oncology clinic for additional chemotherapy and palliative radiation.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults, the average survival rate to discharge after cardiac arrest is about 17%. Many factors lower a patient’s chance of survival, including advanced age, performance status, malignancy, and presence of multiple comorbidities. TH

Dr. Neagle and Dr. Wachsberg are hospitalists and instructors in the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Medical Center in Chicago.

References

- Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santali S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545-549.

- Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):338-342.

- Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297-308.

- La Puma J, Orentlicher D, Moss RJ. Advance directives on admission. Clinical implications and analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. JAMA. 1991;266(3):402-405.

- Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22-31.

- Larkin GL, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Kaye W. Pre-resuscitation factors associated with mortality in 49,130 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the National Registry for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(3):302-311.

- de Vos R, Koster RW, De Haan RJ, Oosting H, van der Wouw PA, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers AJ. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: prearrest morbidity and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):845-850.

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, Webb FJ, Alvarez ER, Wilson GR. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2006;71(2):152-160.

- Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ, Feeley TW. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1905-1912.

- Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1195-1201.

- Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

- Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, Bassetti CL, Wiebe S. Practice parameter: prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67(2):203-210.

Case

A 66-year-old woman with metastatic, non-small-cell carcinoma of the lung, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and hypertension presents with progressive shortness of breath and back pain. Her vital signs are normal, with the exception of tachypnea and an oxygen saturation of 84% on room air. A CT scan shows marked progression of her disease and new metastases to her spine. You begin a discussion about advance directives and code status. During the exchange, the patient asks for guidance regarding resuscitation. How can you best answer her questions about the likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest?

Background

Discussion regarding resuscitation status is a challenge for most hospitalists. The absence of an established relationship, limited time, patient emotion, and difficulty applying general scientific data to a single patient coalesce into a complex interaction. Further complicating matters, patients frequently have unrealistic expectations and overestimate their chance of survival.

Experience has shown that many patients pursue what physicians consider inappropriately aggressive resuscitation measures. Before you have an informed discussion about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) outcomes, patients tend to overestimate their likelihood of survival.1 In 2009, Kaldjian and colleagues found that patients’ initial mean prediction of post-arrest survival was 60.4%, compared with the actual mean of approximately 17%.2,3 Furthermore, nearly half of the patients who initially expressed a desire to receive CPR in the event of cardiac arrest opted to change their code status after they were informed of the actual survival estimates.1,2

Patient autonomy and the law, as defined by the 1990 Patient Self-Determination Act, require that physicians share responsibility with patients in making prospective resuscitation decisions.4 Shared decision-making necessitates a basic discussion on admission within the context of the patient’s prognosis and previously expressed wishes. It might simply include an acknowledgment of a previously completed advance directive. A more complex discussion might require in-depth conversation to address patient performance status, prognosis of acute and chronic illnesses, and education about the typical resuscitation procedures. After listening to the patient’s perspective, the admitting physician can provide input and an interpretation of available data regarding the patient’s likelihood of surviving an in-hospital arrest.

Review of the Data

In the past 40 years, the overall survival rates for cardiac arrest have changed little. Despite numerous advances made in the delivery of medical care, on average, only 17% of all adult arrest patients survive to hospital discharge.3 A variety of factors influence this overall survival rate, both pre-arrest and intra-arrest. Clinical experience allows most physicians to sense what probability a patient has for survival and quality of life following a cardiac arrest. However, anecdotal evidence alone does not provide a patient and their family with the information necessary to make an informed decision regarding code status.

Numerous studies have investigated the patient factors that might influence how likely one is to survive a cardiac arrest. Researchers have paid particular attention to such factors as age, race, presence or absence of a cancer diagnosis, and associated comorbidities. Not surprisingly, older age has been shown to be significantly associated with a lower likelihood of survival to discharge following cardiac arrest.5,6

Ehlenbach and colleagues examined medical data from 433,985 Medicare patients 65 and older who underwent in-hospital CPR.5 Both older age and prior residence in a skilled nursing facility were found to be associated with poorer survival rates.5 Although neither study was able to define an upper-age cutoff for certain peri-arrest mortality, age affects overall survival likelihood in an inverse fashion, with those 85 and older having only a 6% chance of surviving to hospital discharge (see Figure 1, p. 18).1,5,6

The degree of comorbid illness can be used to help predict mortality following cardiac arrest. Review of data from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR) identified particular comorbidities that portend poor post-arrest prognosis.6 In general, the more pre-existing comorbidities a patient has, the less likely they are to survive.6 The presence of hepatic insufficiency, acute stroke, immunodeficiency, renal failure, or dialysis were associated with lower survival rates (see Figure 2, right).6,7

Poor performance status on admission, defined as severe disability, coma, or vegetative state, was predictive of worse outcomes.6 Understandably, patients with hypotension and those who required vasopressors or mechanical ventilation also tended to have lower post-arrest survival rates.6

The presence of a cancer diagnosis is another prognostic factor of interest when considering the chances of surviving an arrest. Classically, CPR was thought to be a futile intervention in this patient population. Specific characteristics within this subset of patients have been shown to influence prognosis, and multiple studies have confirmed that cancer patients generally do worse after an arrest with an overall survival rate of only 6.2%.8 Survival rates tend to be lower in patients with metastatic disease, hematologic malignancies, a history of stem cell transplant, those who arrest within an ICU, and inpatients whose cardiac arrest was anticipated.8,9

In fact, cancer patients whose hospital course followed a path of gradual deterioration showed a 0% survival rate.9 In patients with metastatic disease, poor performance status prior to arrest appeared to account for their particularly poor survival odds (this supports the intuitive, rule-of-thumb that sicker cancer patients have worse outcomes).8

Growing evidence suggests the probability of post-arrest survival is not equal between racial groups. Specifically, black or nonwhite race is associated with higher utilization of CPR and lower survival rates (see Figure 3, right).10 Among Medicare patients, Ehlenbach and colleagues found that black and nonwhite patients were much more likely to undergo CPR, presumably as a result of being less likely to opt for DNR status.5,10 Although this could account for the differences seen in survival rates among these populations, these findings also raise concerns about the possibility of racial disparities in medical care. A subsequent cohort study also suggested that blacks and nonwhites were less likely to survive following cardiac arrest.10 However, adjusted analysis revealed that these differences were strongly associated with the medical center at which these patients received care. Therefore, although being nonwhite does portend worse outcomes following an arrest, the increased risk is likely attributed to the fact that many of these patients receive care at hospitals that have poorer overall CPR performance measures.5,10

Survival is not the only outcome measure patients need to take into account when deciding whether to undergo CPR. Quality of life following resuscitation also warrants consideration. Interestingly, research has shown that neurologic outcomes among the majority of cardiac arrest survivors are generally good.3

Approximately 86% of survivors with intact pre-arrest cerebral performance maintain it on discharge, and only a minority of survivors are eventually declared brain-dead.3 Still, there are certain peri-arrest factors that pose risk for poorer neurologic and functional outcomes. For arrest from a shockable rhythm, time to defibrillation is a key determinant.11 In patients for whom time to defibrillation is greater than two minutes, there is significantly higher risk of permanent disability following cardiac arrest.11

In the event of coma following resuscitation, particular clinical findings can be used to accurately predict poor outcome.12 The absence of pupillary reflexes, corneal reflexes, or absent or extensor motor responses three days after arrest are poor prognostic indicators.12 As a general rule, if a patient does not awaken within three days, neurologic and functional impairment can be expected.12 For those patients who do survive to hospital discharge, more than 50% ultimately will be able to be discharged home.3

However, nearly a quarter will need to be newly placed in a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility.3

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted with hypoxia secondary to both progressive lung malignancy and COPD exacerbation. She had no advanced directives, so the admitting hospitalist, in collaboration with her oncologist, had a detailed discussion regarding her understanding of her disease progression, prognosis, and goals for her remaining time. Her questions regarding survivability of cardiac arrest were answered directly with an estimate of 5% to 10%, based on her age, comorbidities, and the presence of advanced malignancy.

After hearing this information, the patient responded, “I still want everything done.” The hospitalist acknowledged her feelings of wanting to fight on, but asked her to think about what “everything” meant to her. After taking some additional time to reflect with friends and family, the patient was clear that she wanted to continue disease-focused therapies, but did not want to be resuscitated in the event of cardiac or pulmonary arrest.

Eventually, her hypoxia improved with antibiotics, steroids, and bronchodilators. She was discharged home with follow-up in the oncology clinic for additional chemotherapy and palliative radiation.

Bottom Line

For hospitalized adults, the average survival rate to discharge after cardiac arrest is about 17%. Many factors lower a patient’s chance of survival, including advanced age, performance status, malignancy, and presence of multiple comorbidities. TH

Dr. Neagle and Dr. Wachsberg are hospitalists and instructors in the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Medical Center in Chicago.

References

- Murphy DJ, Burrows D, Santali S, et al. The influence of the probability of survival on patients’ preferences regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):545-549.

- Kaldjian LC, Erekson ZD, Haberle TH, et al. Code status discussions and goals of care among hospitalised adults. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(6):338-342.

- Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58(3):297-308.

- La Puma J, Orentlicher D, Moss RJ. Advance directives on admission. Clinical implications and analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. JAMA. 1991;266(3):402-405.

- Ehlenbach WJ, Barnato AE, Curtis JR, et al. Epidemiologic study of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):22-31.

- Larkin GL, Copes WS, Nathanson BH, Kaye W. Pre-resuscitation factors associated with mortality in 49,130 cases of in-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the National Registry for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2010;81(3):302-311.

- de Vos R, Koster RW, De Haan RJ, Oosting H, van der Wouw PA, Lampe-Schoenmaeckers AJ. In-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: prearrest morbidity and outcome. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(8):845-850.

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, Webb FJ, Alvarez ER, Wilson GR. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2006;71(2):152-160.

- Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ, Feeley TW. Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer. 2001;92(7):1905-1912.

- Chan PS, Nichol G, Krumholz HM, et al. Racial differences in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1195-1201.

- Chan PS, Krumholz HM, Nichol G, Nallamothu BK. Delayed time to defibrillation after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):9-17.

- Wijdicks EF, Hijdra A, Young GB, Bassetti CL, Wiebe S. Practice parameter: prediction of outcome in comatose survivors after cardiopulmonary resuscitation (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006;67(2):203-210.