User login

DISCUSSION

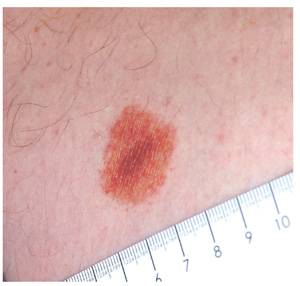

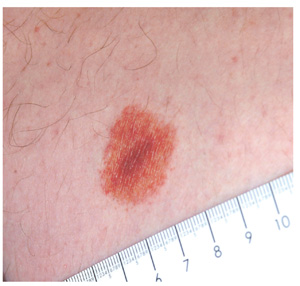

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

DISCUSSION

Punch biopsy confirmed the clinical impression of lichen aureus. This is one of several types of pigmented purpuric dermatoses, all of which involve extravasation of red blood cells and marked localized deposition of hemosiderin.

Some researchers consider all other forms to represent variants of the most common type, Schamberg’s disease, which typically begins with symmetrical involvement of the lower portions of both legs, slowly ascending to mid-thigh or (less often) to the waistline, then just as slowly descending—resolving, in most cases, in months to years. The hallmark of most types of pigmented purpuras is an orange-brown, speckled macular cayenne pepper–like discoloration.

Lichen aureus, one of the least common types, usually appears on the legs of adolescents and young adults. It presents as a solitary copper-colored macule or patch that is nonblanchable on digital pressure, confirming the presence of extravasated red blood cells.

Biopsy shows a T-cell infiltrate centered in the walls of small blood vessels, with endothelial cell swelling, narrowing of vessel lumens, extravasation of red blood cells, and marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages.

The cause of the pigmented purpuric dermatoses is unknown. However, the predominately lower-leg involvement and hemosiderin deposition strongly suggest a role for venous stasis, gravitational dependence, increased activity while upright, or all three.

In addition to lichen aureus and Schamberg’s disease, several other forms of pigmented purpura have been noted. These include:

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (Majocchi’s disease): Small annular plaques with prominent telangiectasias start, as does Schamberg’s, on bilateral distal extremities and spread proximally. The lesions tend to become targetoid (displaying concentric light and dark rings). This type is more common in young women and can occur in areas other than the legs.

• Eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis: This condition involves pruritic eczematous papulosquamous annular lesions with sparse petechiae and hemosiderin staining. Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of spongiosis (intercellular edema of the epidermis). It must be distinguished from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which it can resemble both clinically and histologically.

• Gougerot-Blum syndrome: This condition, also known as pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis, starts with lichenoid papules that fuse into reddish-blue to purple plaques. It is notable among the various pigmented purpuras for the presence of underlying induration, caused by a brisk lymphocytic infiltrate

The differential in this case also includes leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which was successfully ruled out with the biopsy, as were drug rash and contact dermatitis.

TREATMENT

Unfortunately, no good treatment exists for lichen aureus; however, the condition usually fades on its own over time, typically leaving no blemish behind. As it happens, there are no systemic implications of any of the pigmented purpuras.

An 18-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic lesion that has been present on his left inner thigh for several months. The lesion has persisted despite the use of a topical cream containing clotrimazole and betamethasone (applied twice daily for a week) and a subsequent 10-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). Neither treatment seems to have had any impact. There is no history of antecedent trauma. The patient and his family report that no other lesions have been noted and that the patient is quite healthy in other respects. However, there is a family history of melanoma, which has caused the parents more than a little concern. Examination reveals a 3-cm reddish brown polygonal macule with a darker center, located on the left inner thigh. The lesion is neither palpable nor blanchable with digital pressure. No such lesions are seen elsewhere on the patient’s body.