User login

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

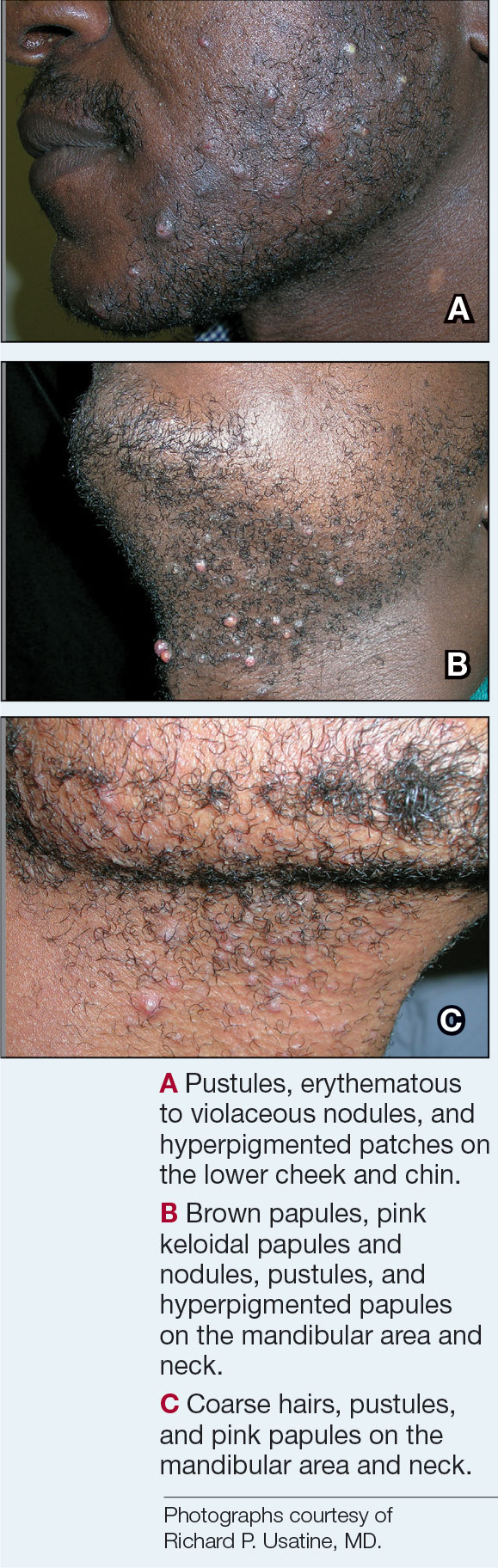

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

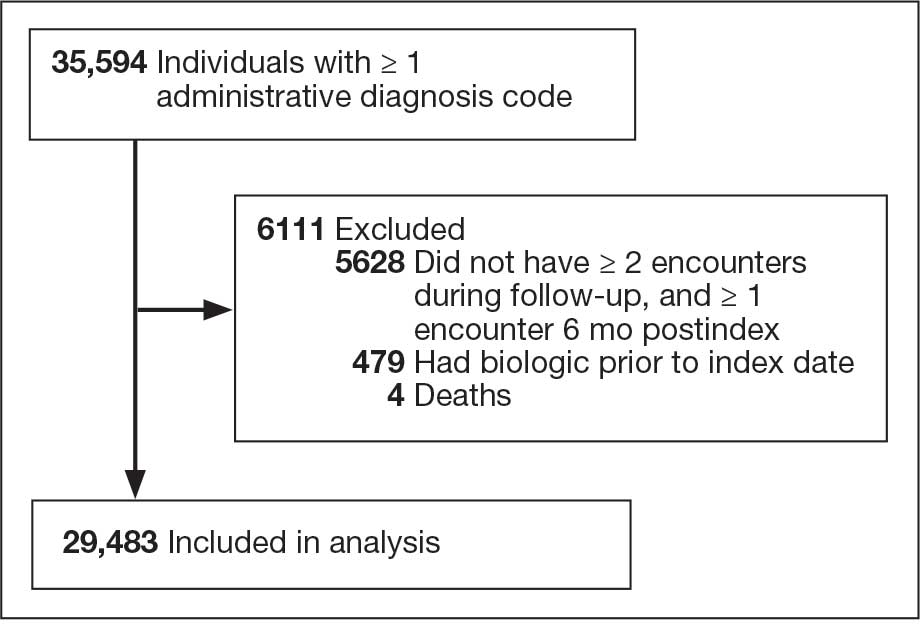

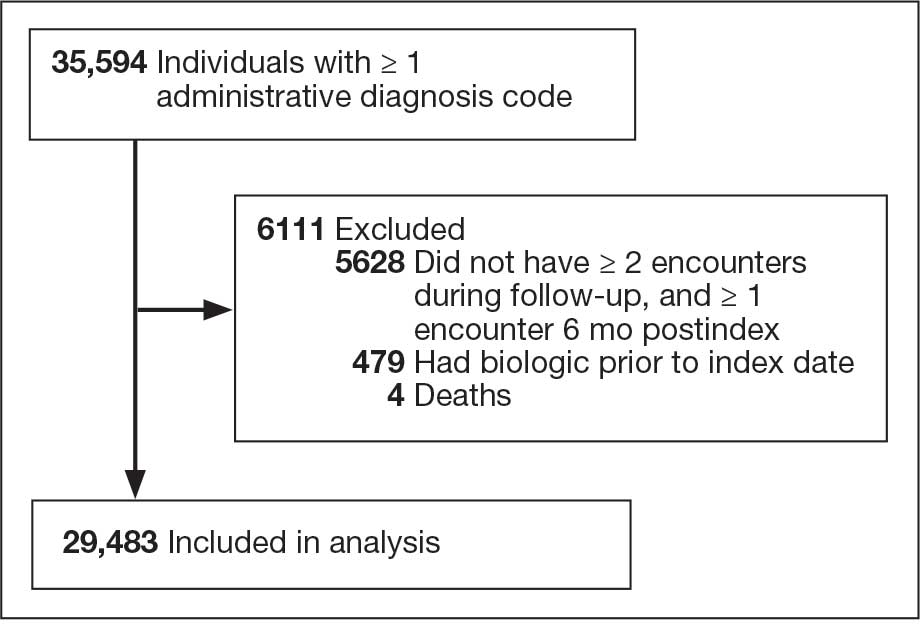

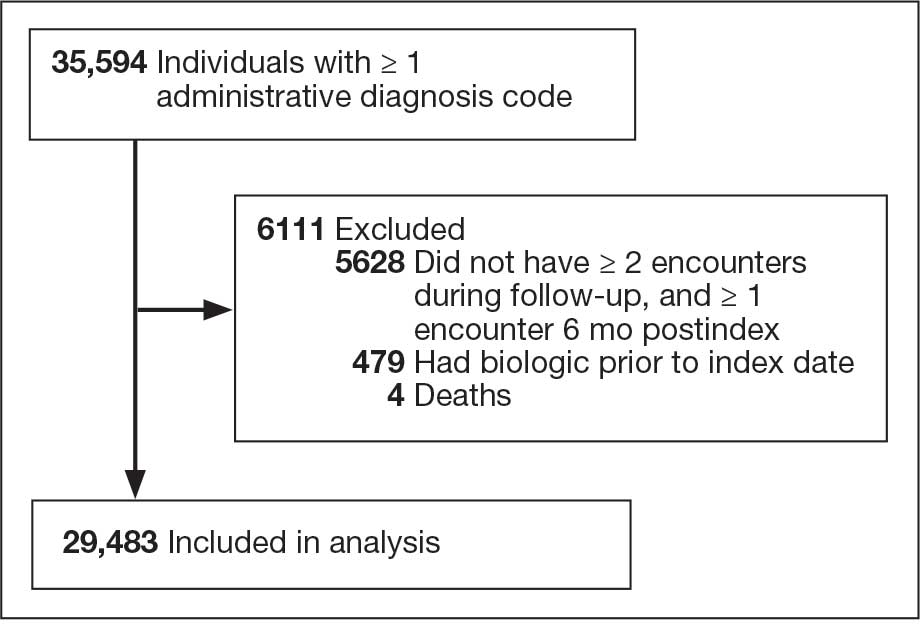

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

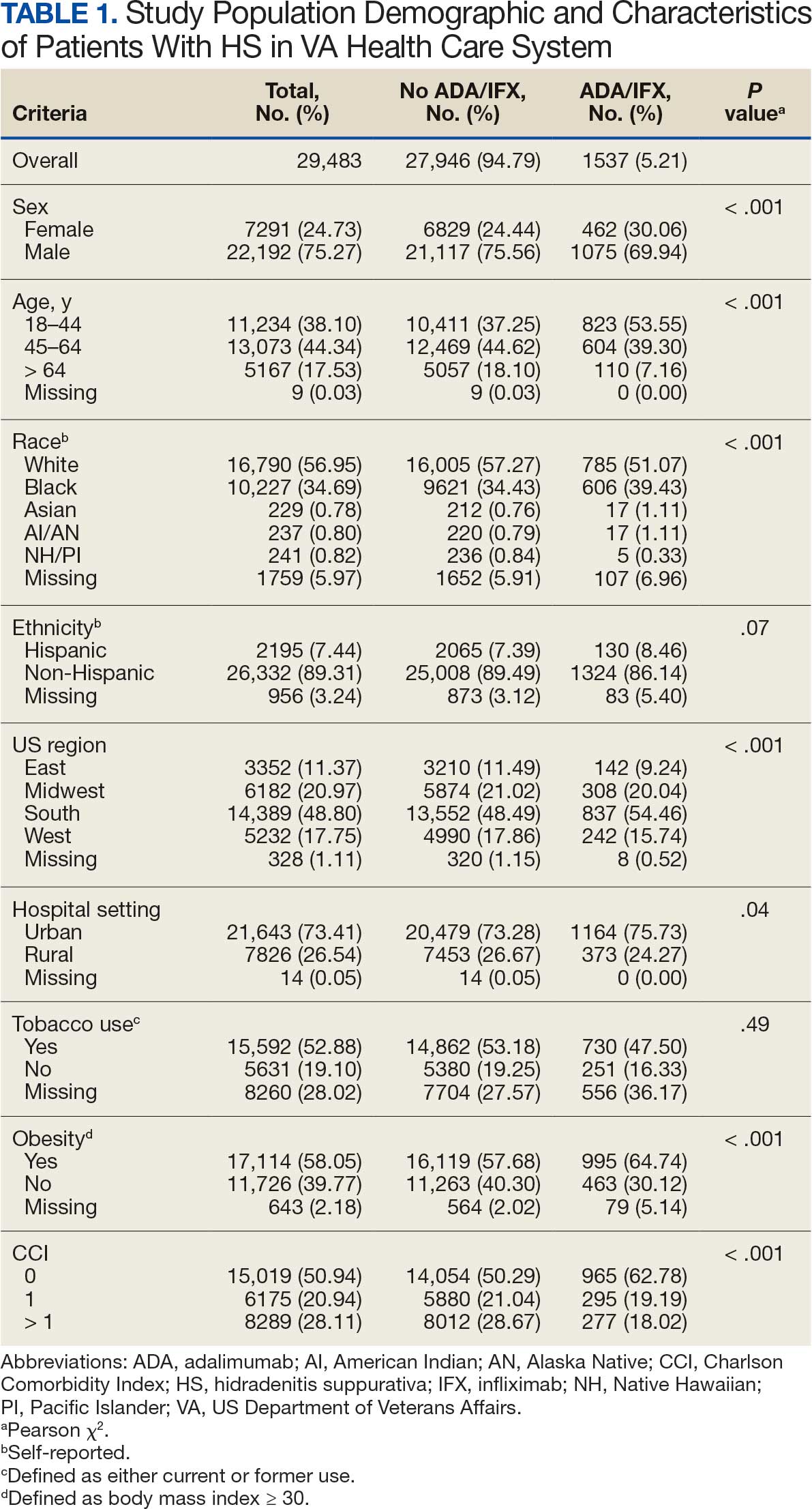

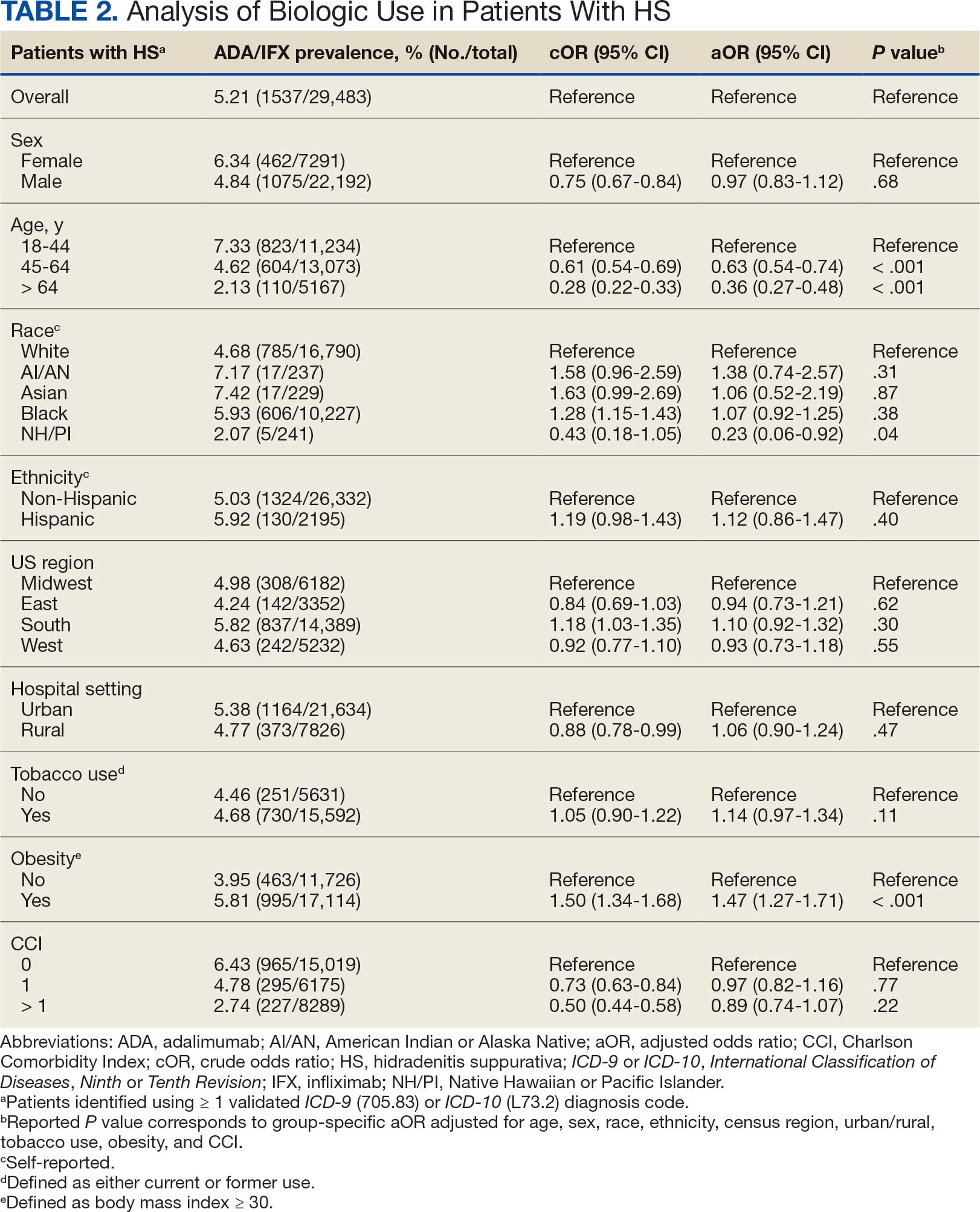

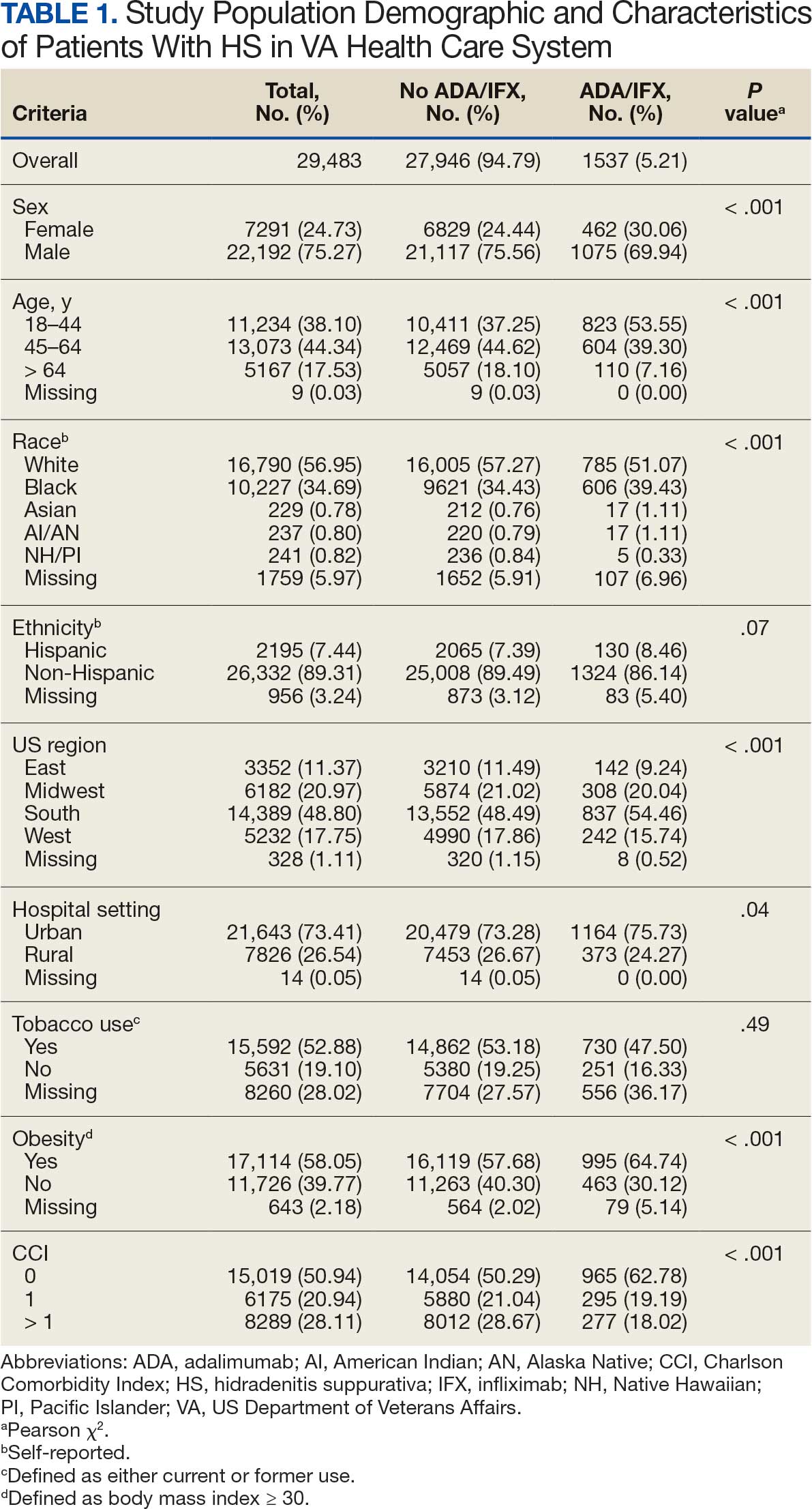

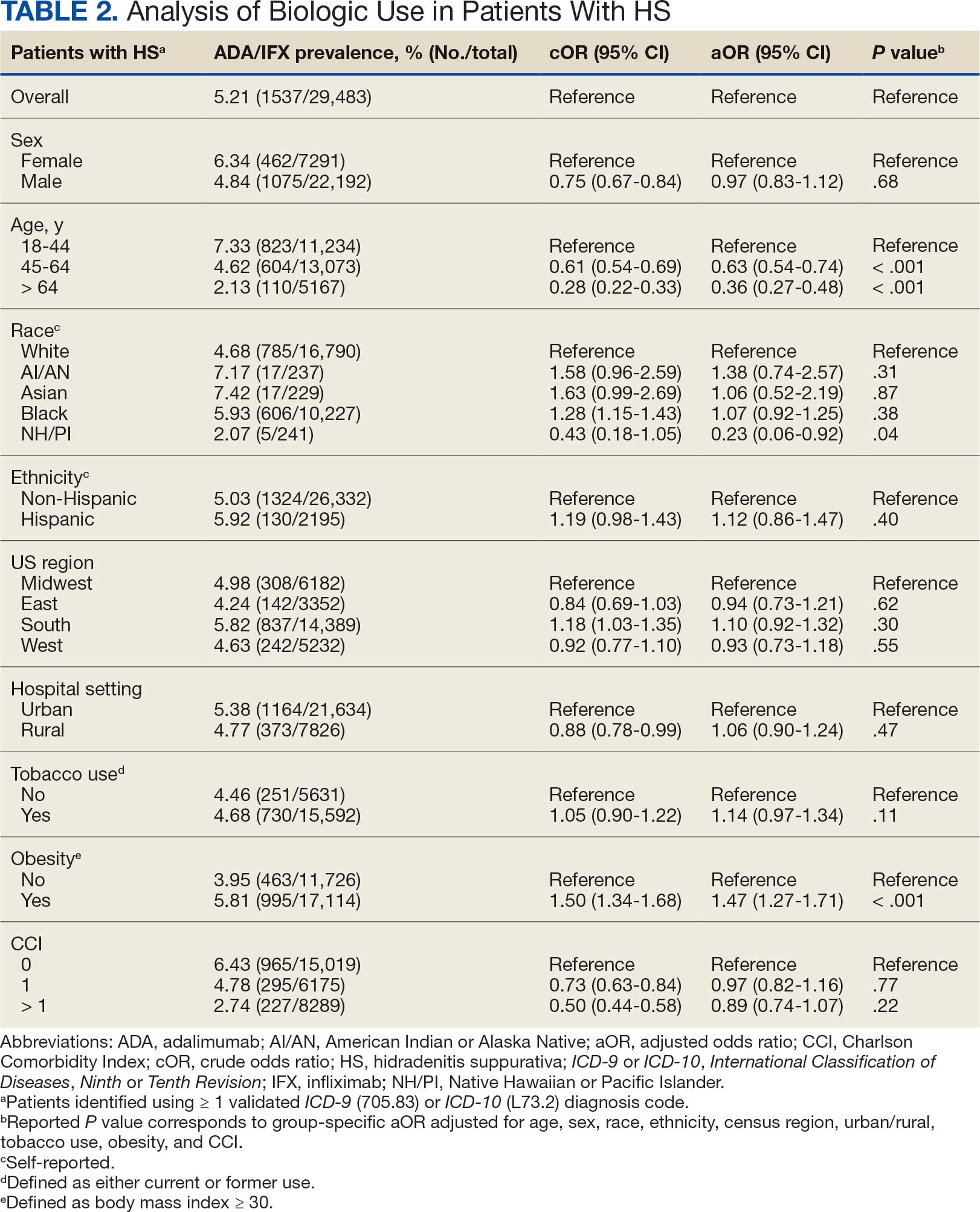

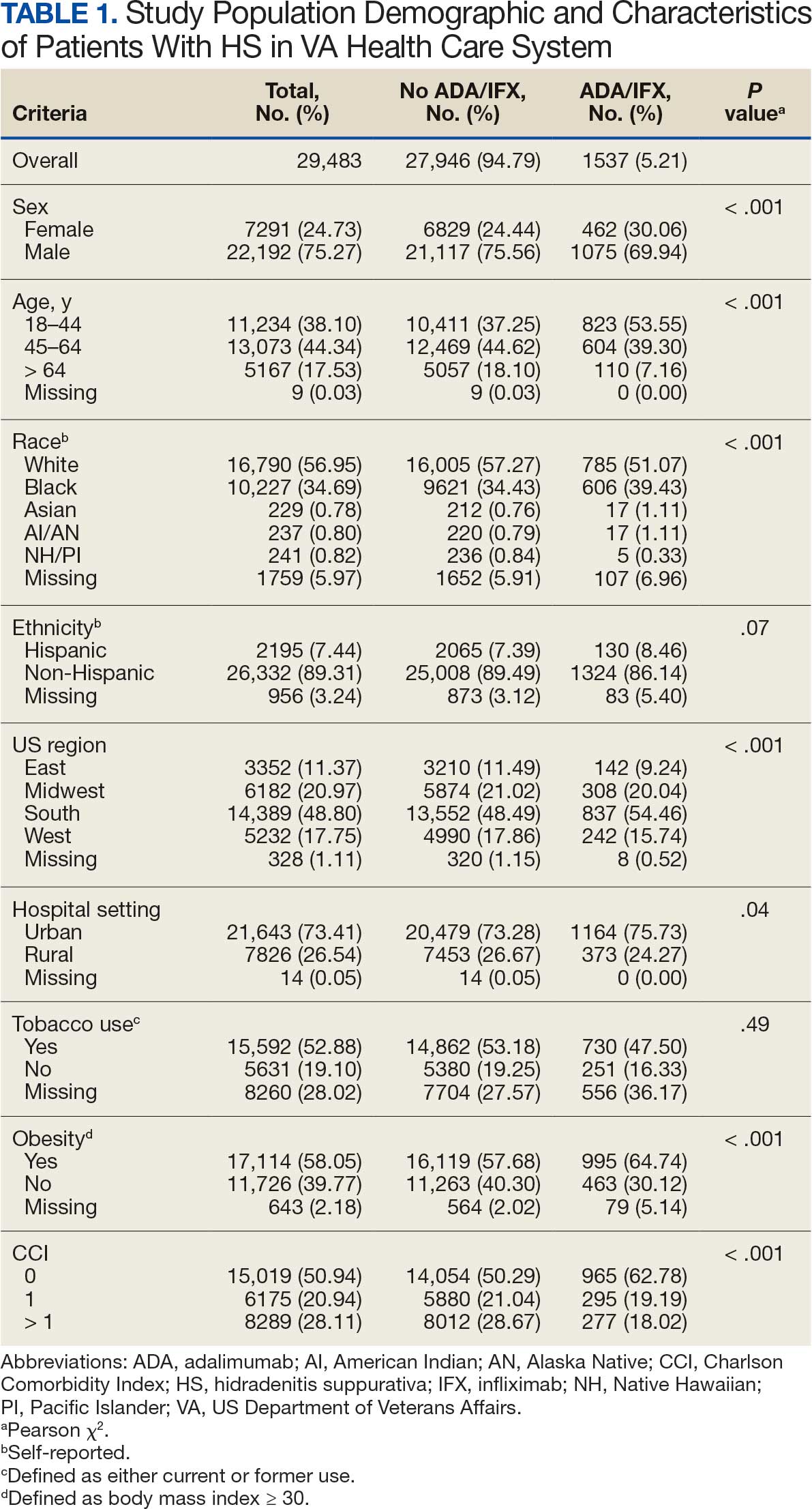

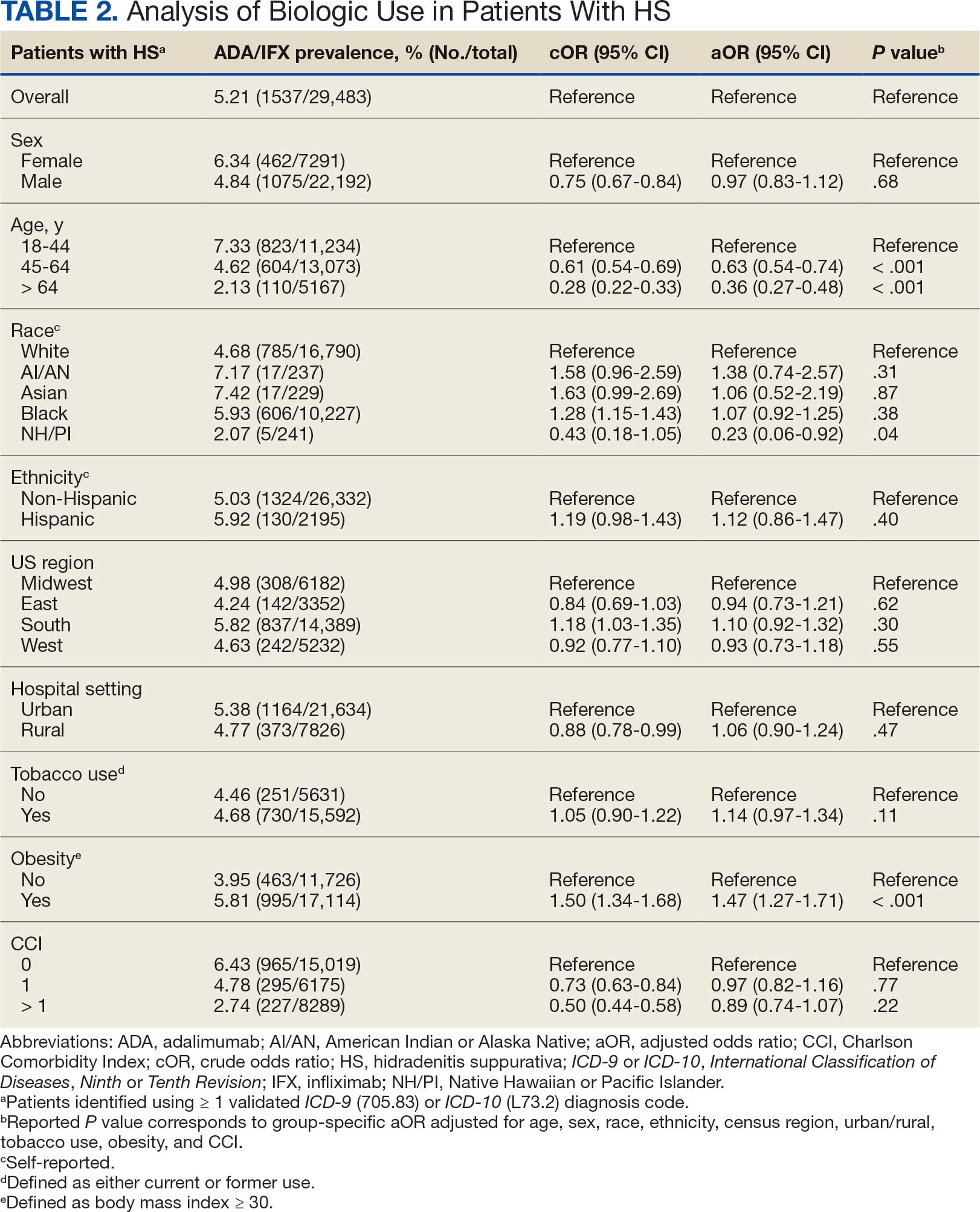

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory skin disorder characterized by painful nodules, abscesses, and tunnels predominantly affecting intertriginous areas of the body.1,2 The condition poses significant challenges in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and quality of life for affected individuals. Various systemic therapies have been explored to manage this debilitating condition, with the emergence of biologic agents offering hope for improved outcomes. In 2015, adalimumab (ADA) was the first biologic approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of HS, followed by secukinumab in 2023 and bimekizumab in 2024. However, the off-label use of other biologics and/or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as infliximab (IFX) has become common practice.3

Although these therapies have demonstrated promising results in the treatment of HS, their widespread use may be hindered by accessibility and cost barriers. Orenstein et al analyzed data from the IBM Explorys platform from 2015 to 2020 and found that only 1.8% of patients diagnosed with HS had been prescribed ADA or IFX.4 More recently, Garg et al examined IBM MarketScan and IBM US Medicaid data from 2015 to 2018 to evaluate trends in clinical care and treatment. The prevalence of ADA and IFX prescriptions among patients with HS ranged from 2.3% to 8.0% (ADA) and 0.7% to 0.9% (IFX) for patients with commercial insurance, and 1.4% to 4.8% (ADA) and 0.5% to 0.7% (IFX) for patients with Medicaid.5 Biologics are often expensive, and the high cost associated with these therapies has been identified as a significant barrier to access for patients with HS, particularly those who lack adequate insurance coverage or face financial constraints.6

Furthermore, these barriers, particularly the financial barriers, are potentially compounded by the demographics of patients most notably affected by HS. In the US, a disproportionate incidence of HS has been noted in specific groups and age ranges, including women, individuals aged 18 to 29 years, and Black individuals.4 Orenstein et al found a statistically significant difference in use of ADA and IFX biologics based on age, sex, and race.4

The aim of this study was to examine the use of 2 biologics (ADA and IFX) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), a unique population in which financial barriers are reduced due to the single-payer government health care system structure. This design allowed for improved isolation and evaluation of variation in ADA and/or IFX prescription rates by demographics and health-related factors among patients with HS. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed these metrics within the VHA.

Methods

This retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of VHA patients used data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository that provides access to longitudinal national electronic health record data for all veterans receiving care through VHA facilities. This study received ethical approval from institutional review boards at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System and VA Salt Lake City Healthcare System. Patient information was deidentified, and patient consent was not required.

Patients with HS were identified using ≥ 1 International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic code: (ICD-9 [705.83] or ICD-10 [L73.2]) between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2021. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years as of January 1, 2011, with ≥ 2 patient encounters during the postdiagnosis follow-up period, and with ≥ 1 encounter 6 months postindex. Patients with a biologic prescription prior to HS diagnosis were excluded. For this study, the term biologics refers to ADA and/or IFX prescriptions, unless otherwise specified. Only ADA and IFX were included in this analysis because ADA, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-á inhibitor, was the only FDA-approved medication at the time of the search, and IFX is another common TNF-α inhibitor used for the treatment of HS.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated logistic regression using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). For each variable, the univariate relationship with biologic prescriptions was examined first, followed by the multivariate relationship controlling for all other variables. The following variables were controlled for in the multivariate models and were chosen a priori: sex, age, race, ethnicity, US region, hospital setting, current or previous tobacco use, obesity (defined as body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).7

Results

Using ICD codes, we identified 29,483 individuals with ≥ 1 HS diagnosis (Figure 1). Of those identified, 1537 patients (5.21%) had been prescribed ≥ 1 biologic. The cohort was predominantly White (60.56%), male (75.27%), obese (59.34%), and had a history of current or previous tobacco use (73.47%) (Table 1). There were significant adjusted differences in prescription rates among veterans with HS based on age, race, and BMI. Notably, there was an age-dependent reduction in the odds of being prescribed a biologic in patients with HS. Compared with patients aged 18 to 44 years, patients aged 45 to 64 years (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54–0.74; P < .001) and patients aged ≥ 65 years (aOR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.48; P < .001) had significantly lower odds of receiving a biologic prescription (Table 2). Compared with White patients with HS, Native Hawaiian (NH) or Pacific Islander (PI) patients were less likely to be prescribed a biologic (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06–0.92; P = .04). Patients with obesity had significantly higher odds of receiving a biologic prescription compared with patients without obesity (aOR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.27– 1.71; P < .001).

Included in Analysis.

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, there were no significant differences in biologic prescription rates for men compared with women (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.83-1.12; P = .68). We observed slight variations in biologic prescriptions between US regions (Midwest 5.0%, East 4.2%, South 5.8%, West 4.6%), none of which were significantly different in the fully adjusted model. No statistically significant differences were found in biologic prescriptions between urban and rural VA settings (5.4% vs 4.8%; aOR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.90–1.24; P = .47). Tobacco use was not associated with the rate of biologic prescription receipt (aOR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.97–1.34; P = .11). After adjusting for other variables (as outlined in Table 2), no significant differences were found between CCI of 0 and 1 (aOR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.82–1.16; P = .77) or between CCI of 0 and 2 (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.74–1.07; P = .22).7

Discussion

The aim of the study was to ascertain potential discrepancies in biologic prescription patterns among patients with HS in the VHA by demographic and lifestyle behavior modifiers. Veteran cohorts are unique in composition, consisting predominantly of older White men within a single-payer health care system. The prevalence of biologic prescriptions in this population was low (5.2%), consistent with prior studies (1.8%–8.9%).4,5

We found a significant difference in ADA/IFX prescription patterns between White patients and NH/PI patients (aOR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.06-0.92; P = .04). Further replication of this result is needed due to the small number of NH/PI patients included in the study (n = 241). Notably, we did not find a significant difference in the odds of Black patients being prescribed a biologic compared with White patients (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.92–1.25; P = .38), consistent with prior studies.4

In line with prior studies, age was associated with the likelihood of receiving a biologic prescription.4 Using the multivariate model adjusting for variables listed in Table 1, including CCI, patients aged 45 to 64 years and > 64 years were less likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients aged 18 to 44 years. HS disease activity could be a potential confounding variable, as HS severity may subside in some people with increasing age or menopause.8

Because different regions in the US have different sociopolitical ideologies and governing legislation, we hypothesized that there may be dissimilarities in the prevalence rates of biologic prescribing across various US regions. However, no significant differences were found in prescription patterns among US regions or between rural and urban settings. Previous research has demonstrated discernible disparities in both dermatologic care and clinical outcomes based on hospital setting (ie, urban vs rural).9-11

Tobacco use has been demonstrated to be associated with the development of HS.12 In a large retrospective analysis, Garg et al reported increased odds of receiving a new HS diagnosis in known tobacco users (aOR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.8–2.0).13 The extent to which tobacco use affects HS severity is less understood. While some studies have found an association between smoking and HS severity, other analyses have failed to find this association.14,15 The effects of smoking cessation on the disease course of HS are unknown.16 This analysis, found no significant difference in prescriptions for biologics among patients with HS comparing current or previous tobacco users with nonusers.

There is a known positive correlation between increasing BMI and HS prevalence and severity that may be explained by the downstream effects of adipose tissue secretion of proinflammatory mediators and insulin resistance in the setting of chronic inflammation.12 This analysis found that patients with HS and obesity were 1.47 times more likely to be prescribed a biologic than patients with HS without obesity, which may be confounded by increased HS severity among patients with obesity. The initial concern when analyzing tobacco use and obesity was that clinician bias may result in a decrease in the prevalence of biologic use in these demographics, which was not supported in this study.

Although we identified few disparities, the results demonstrated a substantial underutilization of biologic therapies (5.2%), similar to the other US civilian studies (1.8-8.9%).4,5 While there is no current universal, standardized severity scoring system to evaluate HS (it is difficult to objectively define moderate to severe HS), estimates have shown that 40.3% to 65.8% of patients with HS have Hurley stage II or III.17-19 Therefore, only a small percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease were prescribed the only FDA-approved medication during this time period. The persistence of this underutilization within a medical system that reduces financial barriers suggests that nonfinancial barriers have a notable role in the underutilization of biologics.

For instance, risk of adverse events, particularly lymphoma and infection, has been cited by patients as a reason to avoid biologics. Additionally, treatment fatigue reduced some patients’ willingness to try new treatments, as did lack of knowledge about treatment options.6,20 Other reported barriers included the frequency of injections and fear of needles.6 Additionally, within the VA, ADA may require prior authorization at the local facility level.21 An established relationship with a dermatologist has been shown to significantly increase the odds of being prescribed a biologic medication in the face of these barriers.4 Future system-wide quality improvement initiatives could be implemented to identify patients with HS not followed by dermatology, with the goal of establishing care with a dermatologist.

Limitations

Limitations to this study include an inability to categorize HS disease severity and assess the degree to which disease severity confounded study findings, particularly in relation to tobacco use and obesity. The generalizability of this study is also limited because of the demographic characteristics of the veteran patient population, which is predominantly older, White, and male, whereas HS disproportionately affects younger, Black, and female individuals in the US.22 Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into the use of biologic therapies for veteran populations with HS using a national dataset.

Conclusions

This study was performed within a single-payer government medical system, likely reducing or removing the financial barriers that some patient populations may face when pursuing biologics for HS treatment. However, the prevalence of biologic use in this population was low overall (5.2%), suggesting that other factors play a role in the underutilization of biologics in HS. Consistent with previous studies, younger individuals were more likely to be prescribed a biologic, and no difference in prescription rates between Black and White patients was observed. Unlike previous studies, no significant difference in prescription rates between men and women was observed.

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

- Tchero H, Herlin C, Bekara F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis of therapeutic interventions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2019;85:248-257. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_69_18

- Shih T, Lee K, Grogan T, et al. Infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15691. doi:10.1111/dth.15691

- Orenstein LAV, Wright S, Strunk A, et al. Low prescription of tumor necrosis alpha inhibitors in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1399-1401. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.108

- Garg A, Naik HB, Alavi A, et al. Real-world findings on the characteristics and treatment exposures of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from US claims data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:581-594. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00872-1

- De DR, Shih T, Fixsen D, et al. Biologic use in hidradenitis suppurativa: patient perspectives and barriers. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:3060-3062. doi:10.1080/09546634.2022.2089336

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373- 383. doi:10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:389-392. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x

- Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-428.e2. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020

- Wu YP, Parsons B, Jo Y, et al. Outdoor activities and sunburn among urban and rural families in a Western region of the US: implications for skin cancer prevention. Prev Med Rep. 2022;29:101914. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101914

- Mannschreck DB, Li X, Okoye G. Rural melanoma patients in Maryland do not present with more advanced disease than urban patients. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27. doi:10.5070/D327553607

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.059

- Garg A, Papagermanos V, Midura M, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa among tobacco smokers: a population- based retrospective analysis in the U.S.A. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:709-714. doi:10.1111/bjd.15939

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GBE, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831- 839. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

- Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, Wolkenstein P, et al. Clinical characteristics of a series of 302 French patients with hidradenitis suppurativa, with an analysis of factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.013

- Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216- 221. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population- based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.255

- Vanlaerhoven AMJD, Ardon CB, van Straalen KR, et al. Hurley III hidradenitis suppurativa has an aggressive disease course. Dermatology. 2018;234:232-233. doi:10.1159/000491547

- Shahi V, Alikhan A, Vazquez BG, et al. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Dermatology. 2014;229:154-158. doi:10.1159/000363381

- Salame N, Sow YN, Siira MR, et al. Factors affecting treatment selection among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:179. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5425

- VA Formulary Advisor: ADALIMUMAB-BWWD INJ,SOLN. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated December 17, 2025. Accessed January 15, 2026. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/drugs/4042383-ADALIMUMAB-BWWD-INJ-SOLN

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118- 122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Cross-Sectional Analysis of Biologic Use in the Treatment of Veterans With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Early Infantile Hemangioma Diagnosis Is Key in Skin of Color

Richard P. Usatine, MD

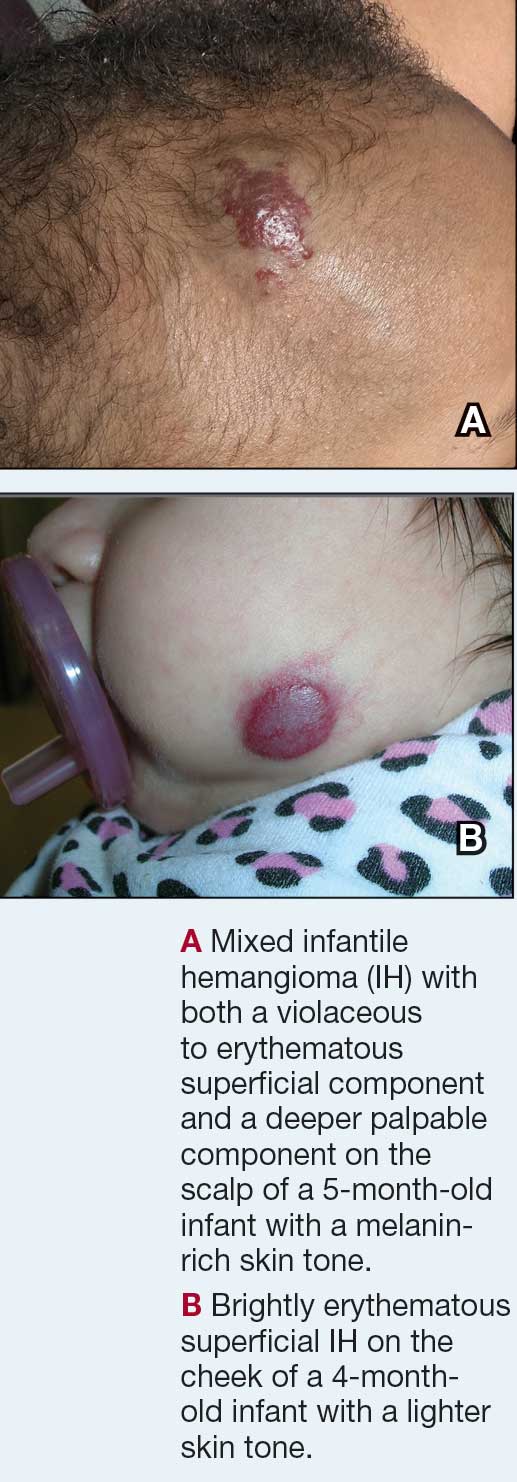

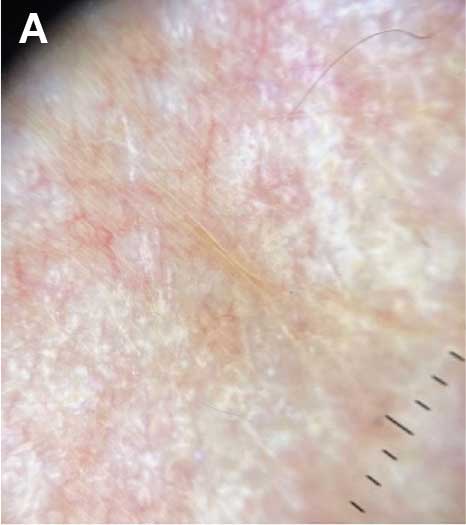

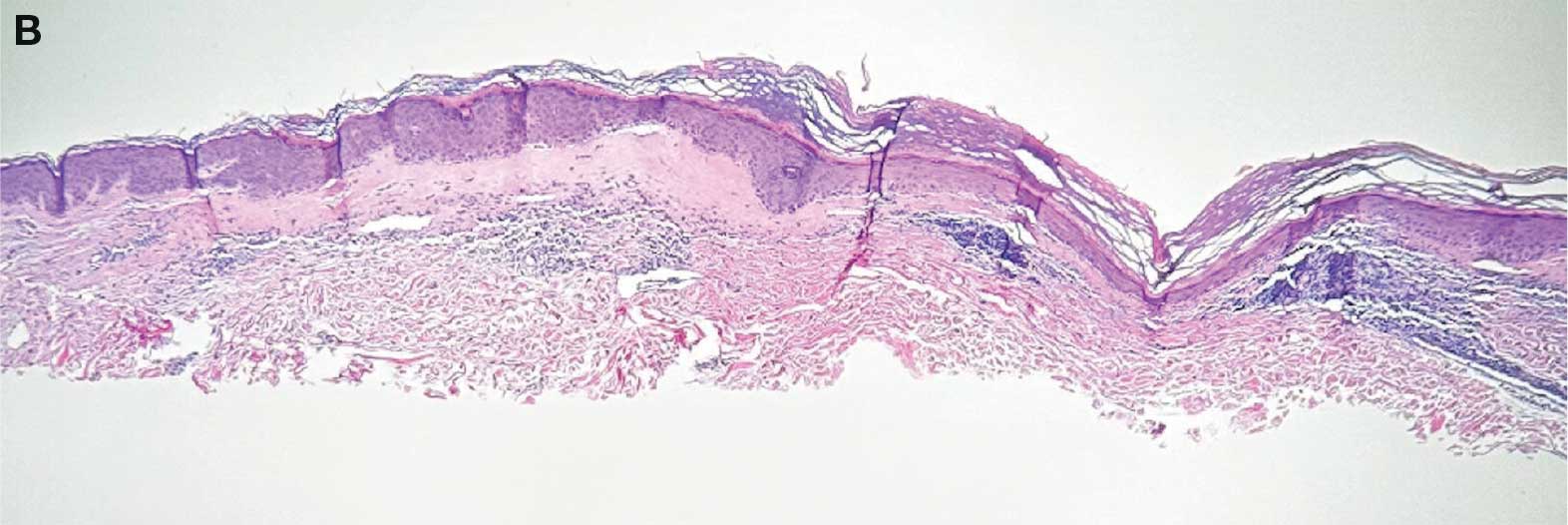

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

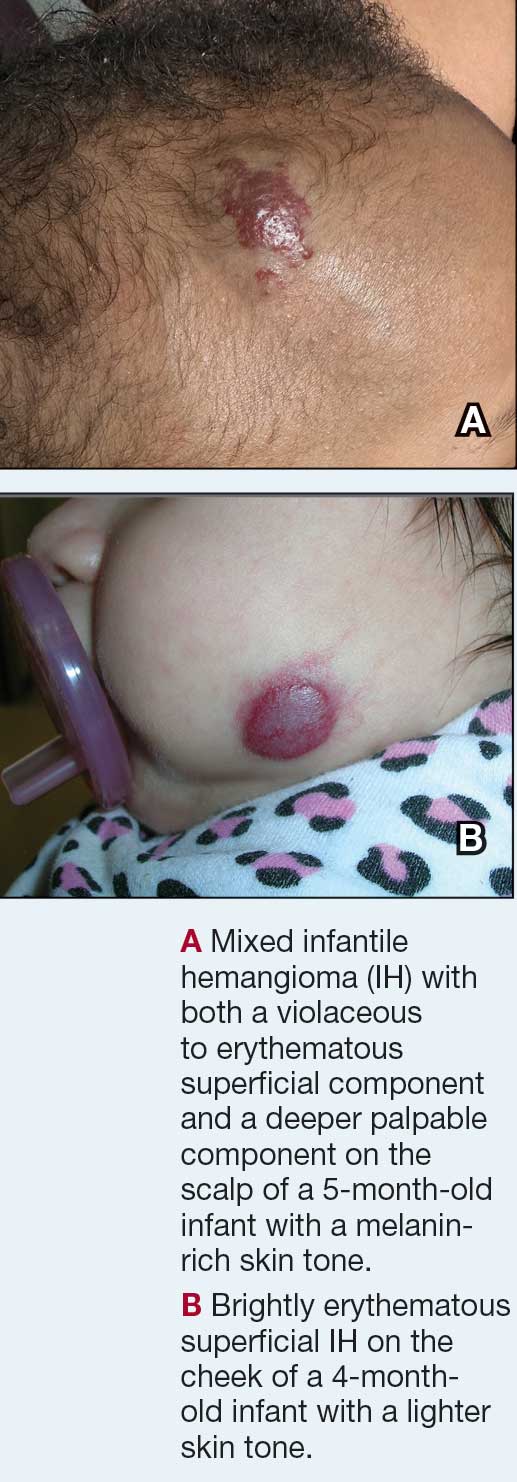

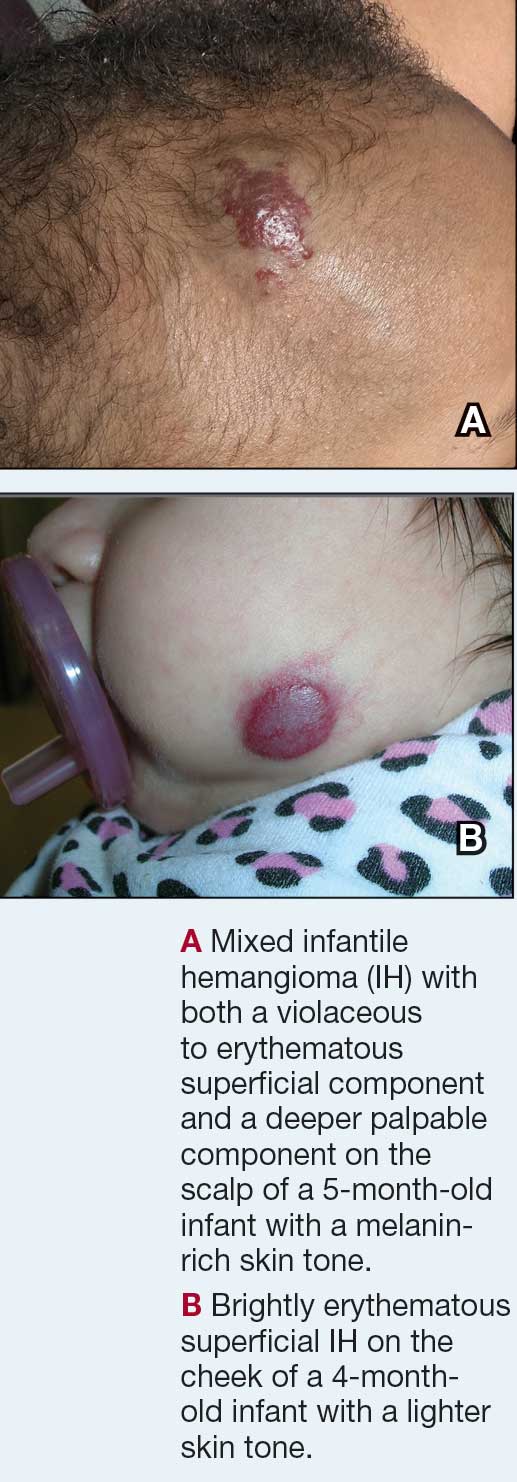

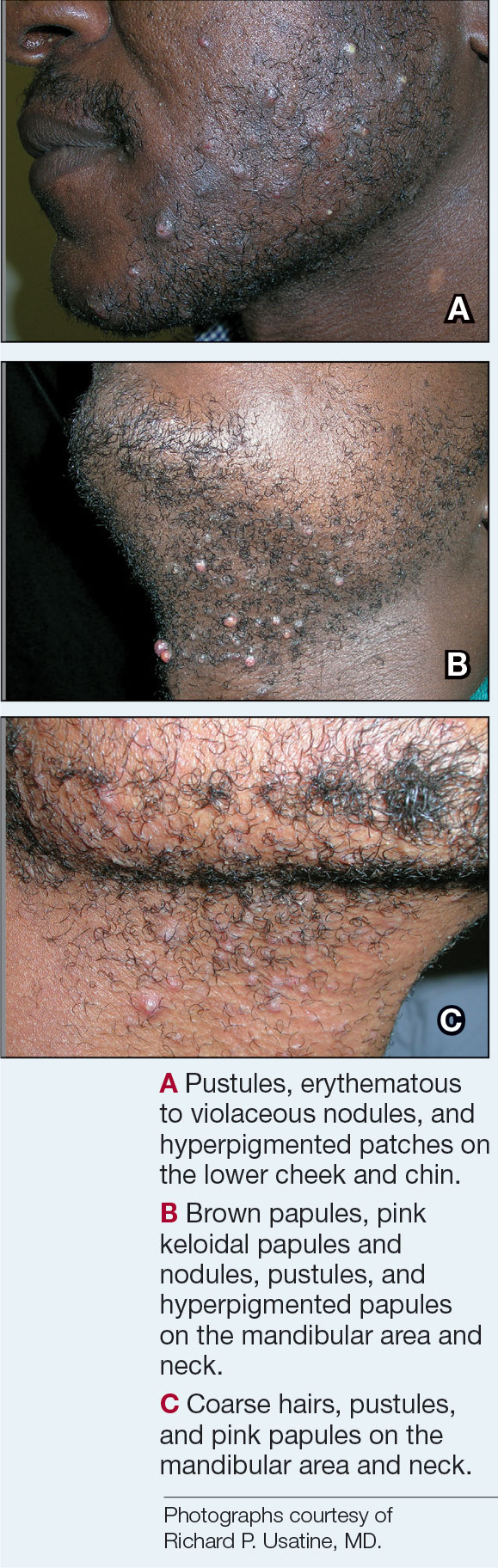

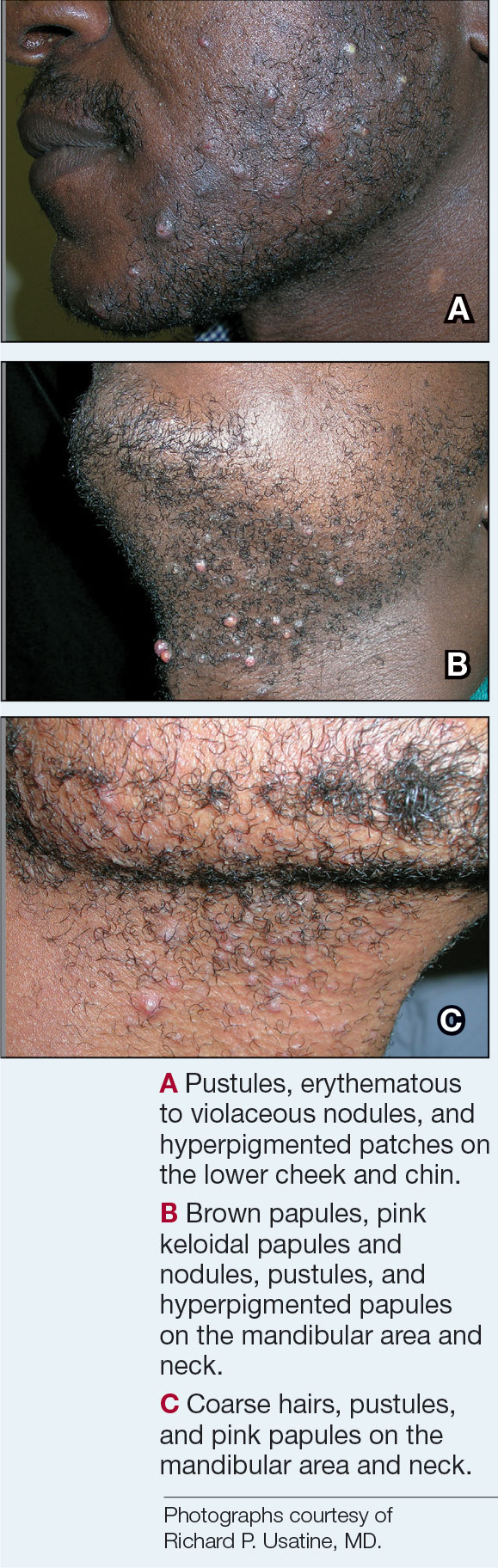

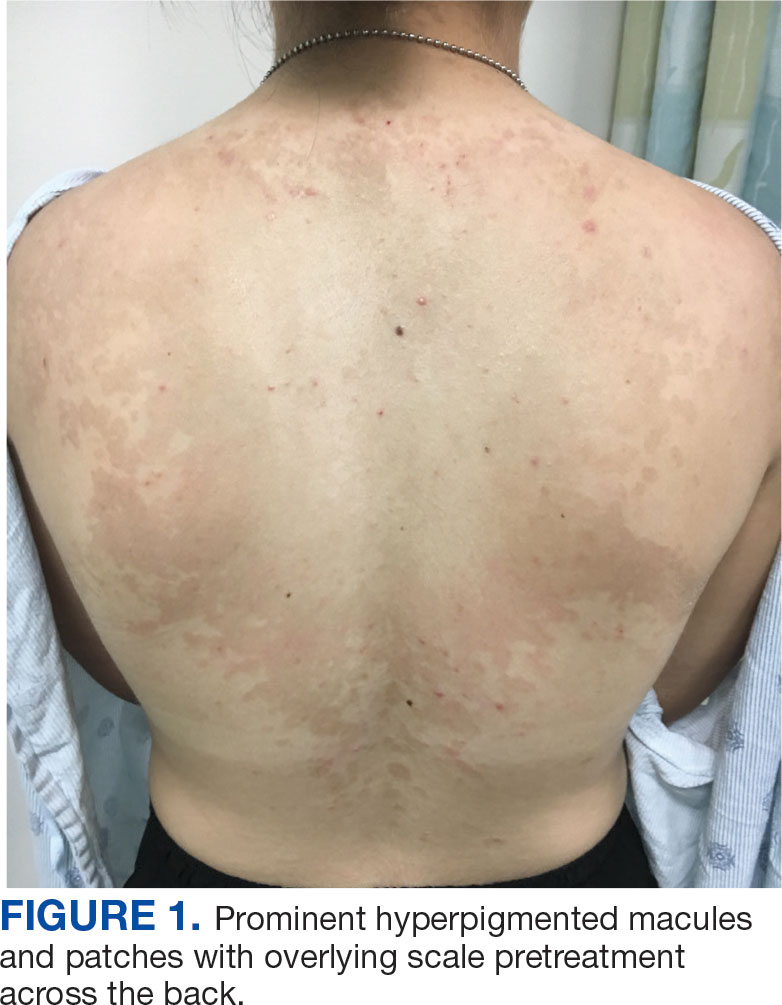

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

Richard P. Usatine, MD

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

Richard P. Usatine, MD

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor of infancy, appearing within the first few weeks of life and typically reaching peak size by age 3 to 5 months.1 It classically manifests as a raised or flat bright-red lesion in the upper dermis of the skin and/or subcutaneous tissue and can vary in number, size, shape, and location.2 It is characterized by a rapid proliferative phase, especially between 5 and 8 weeks of age, followed by gradual spontaneous regression over 1 to 10 years.1-3

Infantile hemangiomas are categorized based on depth (superficial, deep, or mixed) and distribution pattern (focal, multifocal, segmental, or indeterminate).4 In most cases, complete regression occurs by age 4 years, but there can be residual telangiectasia, fibrofatty tissue, and/or scarring.1,4 About 10% to 15% of IHs result in complications that require medical intervention (eg, visual, airway, or auditory compromise; ulceration; disfigurement); ideally, these patients should be referred to a specialist by 5 weeks of age.4 Prompt assessment of IH severity is essential to prevent or mitigate potential complications and ultimately improve outcomes.3 Social drivers of health contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of hemangiomas, leading to increased complications in some patient populations.5-7

Epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas are estimated to manifest in 4.5% of infants in the United States.1 The most common type is superficial IH, typically found on the head or neck.5 Risk factors in infants include female sex, White race, premature birth, and low birth weight (< 1000 g).1,3 Maternal risk factors include advanced gestational age (ie, > 35 years), multiple gestations, family history of IH, tobacco use, use of progesterone therapy during pregnancy, and pre-eclampsia.1,3

Focal IH typically manifests as a single localized lesion that can occur anywhere on the body.2,3 In contrast, segmental IH manifests in a linear pattern and/or is distributed on a large anatomic area, most commonly on the face and less frequently the extremities and trunk.

Key Clinical Features

Superficial IH in patients with darker skin tones may appear as a dark-red or violaceous papule or plaque compared to bright red in lighter skin tones.5 Deep IH may appear as a soft, round, flesh-colored or blue-hued subcutaneous mass, the color of which may be harder to appreciate in those with darker skin tones.5

Worth Noting

Complications from IH may require imaging, close follow-up, systemic therapy, multidisciplinary care, and advanced health literacy and patient/family navigation. Multifocal IHs (≥ 5 lesions) are more likely to be associated with infantile hepatic hemangiomas.2,3 Large (> 5 cm) segmental IHs on the face and lumbosacral area require further evaluation for PHACES (posterior fossa malformation, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, cardiac defects, eye anomalies, and sternal raphe/cleft defects) and LUMBAR (lower-body segmental IH; urogenital anomalies and ulceration; myelopathy; bony deformities; anorectal malformations and arterial anomalies; and renal anomalies) syndromes, which are more common in patients of Hispanic ethnicity.2,3

The Infantile Hemangioma Referral Score is a recently validated tool that can assist primary care physicians in timely referral of IHs requiring early specialist intervention.4,9 It takes into account the location, number, and size of the lesions and the age of the patient; these factors help to determine which IHs may be managed conservatively vs those that may require treatment to prevent life-threatening complications.1-3

Systemic corticosteroids historically have been the primary treatment for IH; however, in the past decade, propranolol oral solution (4.28 mg/mL) has become the first-line therapy for most infants requiring systemic management.10 It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for proliferating IH, with treatment initiation as young as 5 weeks corrected age.11 As a nonselective beta-blocker, propranolol is believed to reduce IHs through vasoconstriction or by inhibition of angiogenesis.1,4,10

For small superficial IHs, treatment options include timolol maleate ophthalmic solution 0.5% (one drop applied twice daily to the IH) or pulsed dye laser therapy.4,10 Surgical excision typically is avoided during infancy due to concerns about anesthetic risks and potential blood loss.4,10 Surgery is reserved for cases involving residual fibrofatty tissue, postinvolution scarring, obstruction of vital structures, or lesions in aesthetically sensitive areas as well as when propranolol is contraindicated.4,10

Health Disparity Highlight

Infants with skin of color and those of lower socioeconomic status (SES) face a heightened risk for delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at the initial evaluation for IH.5,7 Access barriers such as geographic limitations to specialty services, lack of insurance, underinsurance, and language differences impact timely diagnosis and treatment.5,6 Implementation of telemedicine services in areas with limited access to specialists can facilitate early evaluation and risk stratification for IH.12

A retrospective cohort study of 804 children seen at a large academic hospital found that those of lower SES were more likely to seek care after 3 months of age than their higher-SES counterparts.6 Those who presented after 6 months of age also had higher IH severity scores compared to their counterparts with higher SES.6 Delayed access to care may cause children to miss the critical treatment window during the rapid proliferative growth phase.6,12 However, children insured through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program who participated in institutional care management programs (which assist in scheduling specialty care appointments within the institution) sought treatment earlier regardless of their SES, suggesting that such programs may help reduce disparities in timely access for children of lower SES.6

An epidemiologic study analyzing the demographics of children hospitalized across the United States demonstrated that Black infants with IH were more likely to belong to the lowest income quartile compared with White infants or those of other races. They also were 2 times older on average at initial presentation (1.8 vs 1.0 years), experienced longer hospitalizations (16.4 vs 13.8 days), and underwent more IH-related procedures than White infants and infants of other races (2.4, 1.9, and 2.1, respectively).7

These and other factors may contribute to missed windows of opportunity for timely treatment of high-risk IHs in patients with darker skin tones and/or those facing challenges stemming from social drivers of health.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:E20183475.

- Frieden IJ, Püttgen KB, Drolet BA, et al. Management of infantile hemangiomas during the COVID pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:412-418.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390:85-94.

- Mitra R, Fitzsimons HL, Hale T, et al. Recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of infantile haemangioma development. Br J Dermatol. 2024;191:661-669.

- Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392.

- Sebaratnam DF, Rodríguez Bandera AL, Wong LCF, et al. Infantile hemangioma. Part 2: management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1395-1404.

- Taye ME, Shah J, Seiverling EV, et al. Diagnosis of vascular anomalies in patients with skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024;17:54-62.

- Lie E, Psoter KJ, Püttgen KB. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with delayed access to care for infantile hemangioma: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:E221-E230.

- Kumar KD, Desai AD, Shah VP, et al. Racial discrepancies in presentation of hospitalized infantile hemangioma cases using the Kids’ Inpatient Database. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:E1092.

- Chiller KG, Passaro D, Frieden IJ. Hemangiomas of infancy: clinical characteristics, morphologic subtypes, and their relationship to race, ethnicity, and sex. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1567.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Baselga Torres E, Weibel L, et al. The infantile hemangioma referral score: a validated tool for physicians. Pediatrics. 2020;145:E20191628.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602.