User login

Drug store and supermarket shelves display aisle after aisle of OTC medications that alleviate the common symptoms of upper respiratory infections. Despite the easy availability of symptom relief, a significant number of people consult clinicians in primary care offices, emergency departments (EDs), and walk-in or convenient care clinics for help when they feel that they’re “coming down with something.” During these visits, many of these patients expect, and sometimes demand, antibiotics.

Antibiotics may be viewed by the patient as a quick fix, with the demand undoubtedly fueled by busy lifestyles, long work hours, and little time for patients to stay home while ill. Patients so inclined may “doctor shop” if their demands are not met; clinicians know better but may feel pressure to “satisfy the customer” and may rationalize that an antibiotic might prove helpful in a particular case.

Lee et al studied outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTI), including acute nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, influenza, pharyngitis, and sinusitis. In 2000, antibiotics were prescribed during outpatient visits for ARTI to 64% of patients; by 2010, that percentage had increased to 73%.1 Although antibiotics are neither effective nor appropriate for the treatment of ARTI, most of which are viral infections, they are commonly prescribed. Further, while 17% of ARTI prescriptions in 2000 were for broad-spectrum antibiotics, that percentage jumped to 46% in 2010.1,2

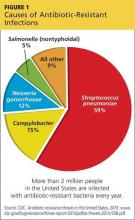

Patient insistence on antibiotics may stem either from little knowledge of or little regard for the health problems caused by unnecessary antibiotic use. For example, one study found that 19.3% of drug-related ED visits were related to systemic antibiotics; nearly 80% of those were for allergic reactions.3,4 With an estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions considered inappropriate, the overuse of antibiotics creates unnecessary personal health risks and health care expenditures. Further, a more serious consequence of this overuse is the growing public health problem of antibiotic resistance (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinicians are ideally positioned to address these issues by incorporating effective, proactive strategies into selected patient encounters to specifically explain appropriate versus inappropriate antibiotic use.

Continue for patient handouts >>

One approach is to merge accurate, powerful messages about antibiotics with helpful information about effective OTC products to both enlighten patients and offer them the symptomatic relief they seek. The CDC has taken the lead in this area with its “Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work” initiative, which includes a variety of materials for both health care providers and patients.5

Inspired by the unmet need for written communications that explain viral and bacterial illnesses in simple terms and the reasons why taking antibiotics for the former is a bad idea, we developed two handouts for adult patients who present to the clinician’s office with viral respiratory illnesses.

The first is entitled “Prescription for Recovery From Your Viral Respiratory Illness” [download PDF]. Intended to be duplicated and designed with primary care use in mind, it can be customized for specialty use as well.

This “prescription” handout addresses common complaints of fever, pain (eg, sore throat, body aches, headache), cough, congestion (chest, nose, sinuses), and sneezing/runny nose. Clinicians can check off the appropriate treatments for an individual patient, who can use it as a handy reference to purchase the recommended OTC products and/or for selecting products or preparing helpful remedies at home. Blank lines at the bottom provide space for you to write in your OTC preferences and allow you to customize patient instructions.

The second patient handout is entitled “Antibiotics: When You Need Them, When You Don’t, and What to Take When You Don’t” [download PDF]. This focused patient teaching tool offers an overview of

• Viral and bacterial respiratory illnesses and what the patient should do if he or she has one or the other (including when to see a clinician)

• Some helpful OTC and home treatments for symptoms of viral respiratory illnesses

• When antibiotics are indicated and when they’re not—and why

• The serious problems caused by unnecessary use of antibiotics.

This brief guide can be used as a general informational handout that can, for example, be given, mailed, or e-mailed to all adult patients at the start of cold and flu season and retained by them for reference. It can also be provided along with the “prescription” handout to patients with ARTIs who visit your office. In the latter situation, the patient leaves your office with concrete information and guidance for appropriate care of his or her viral respiratory illness—but without a prescription for antibiotics. As with the “prescription” handout, this brief guide may be duplicated or customized as needed.

To download the handouts: Click here.

REFERENCES

1. Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000-2010. BMC Med. 2014;12:96.

2. CDC. Antibiotics: will they work when you really need them? www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/factsheets/antibiotics.html#MustAct. Accessed August 14, 2014.

3. Shehab N, Patel P, Srinivasan A, Budnitz D. Emergency department visits for antibiotic associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743.

4. CDC. Adverse drug events from select medication classes. www.cdc.gov/MedicationSafety/program_focus_activities.html. Accessed August 4, 2014.

5. CDC. Get smart: know when antibiotics work. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/. Accessed August 14, 2014.

Drug store and supermarket shelves display aisle after aisle of OTC medications that alleviate the common symptoms of upper respiratory infections. Despite the easy availability of symptom relief, a significant number of people consult clinicians in primary care offices, emergency departments (EDs), and walk-in or convenient care clinics for help when they feel that they’re “coming down with something.” During these visits, many of these patients expect, and sometimes demand, antibiotics.

Antibiotics may be viewed by the patient as a quick fix, with the demand undoubtedly fueled by busy lifestyles, long work hours, and little time for patients to stay home while ill. Patients so inclined may “doctor shop” if their demands are not met; clinicians know better but may feel pressure to “satisfy the customer” and may rationalize that an antibiotic might prove helpful in a particular case.

Lee et al studied outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTI), including acute nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, influenza, pharyngitis, and sinusitis. In 2000, antibiotics were prescribed during outpatient visits for ARTI to 64% of patients; by 2010, that percentage had increased to 73%.1 Although antibiotics are neither effective nor appropriate for the treatment of ARTI, most of which are viral infections, they are commonly prescribed. Further, while 17% of ARTI prescriptions in 2000 were for broad-spectrum antibiotics, that percentage jumped to 46% in 2010.1,2

Patient insistence on antibiotics may stem either from little knowledge of or little regard for the health problems caused by unnecessary antibiotic use. For example, one study found that 19.3% of drug-related ED visits were related to systemic antibiotics; nearly 80% of those were for allergic reactions.3,4 With an estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions considered inappropriate, the overuse of antibiotics creates unnecessary personal health risks and health care expenditures. Further, a more serious consequence of this overuse is the growing public health problem of antibiotic resistance (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinicians are ideally positioned to address these issues by incorporating effective, proactive strategies into selected patient encounters to specifically explain appropriate versus inappropriate antibiotic use.

Continue for patient handouts >>

One approach is to merge accurate, powerful messages about antibiotics with helpful information about effective OTC products to both enlighten patients and offer them the symptomatic relief they seek. The CDC has taken the lead in this area with its “Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work” initiative, which includes a variety of materials for both health care providers and patients.5

Inspired by the unmet need for written communications that explain viral and bacterial illnesses in simple terms and the reasons why taking antibiotics for the former is a bad idea, we developed two handouts for adult patients who present to the clinician’s office with viral respiratory illnesses.

The first is entitled “Prescription for Recovery From Your Viral Respiratory Illness” [download PDF]. Intended to be duplicated and designed with primary care use in mind, it can be customized for specialty use as well.

This “prescription” handout addresses common complaints of fever, pain (eg, sore throat, body aches, headache), cough, congestion (chest, nose, sinuses), and sneezing/runny nose. Clinicians can check off the appropriate treatments for an individual patient, who can use it as a handy reference to purchase the recommended OTC products and/or for selecting products or preparing helpful remedies at home. Blank lines at the bottom provide space for you to write in your OTC preferences and allow you to customize patient instructions.

The second patient handout is entitled “Antibiotics: When You Need Them, When You Don’t, and What to Take When You Don’t” [download PDF]. This focused patient teaching tool offers an overview of

• Viral and bacterial respiratory illnesses and what the patient should do if he or she has one or the other (including when to see a clinician)

• Some helpful OTC and home treatments for symptoms of viral respiratory illnesses

• When antibiotics are indicated and when they’re not—and why

• The serious problems caused by unnecessary use of antibiotics.

This brief guide can be used as a general informational handout that can, for example, be given, mailed, or e-mailed to all adult patients at the start of cold and flu season and retained by them for reference. It can also be provided along with the “prescription” handout to patients with ARTIs who visit your office. In the latter situation, the patient leaves your office with concrete information and guidance for appropriate care of his or her viral respiratory illness—but without a prescription for antibiotics. As with the “prescription” handout, this brief guide may be duplicated or customized as needed.

To download the handouts: Click here.

REFERENCES

1. Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000-2010. BMC Med. 2014;12:96.

2. CDC. Antibiotics: will they work when you really need them? www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/factsheets/antibiotics.html#MustAct. Accessed August 14, 2014.

3. Shehab N, Patel P, Srinivasan A, Budnitz D. Emergency department visits for antibiotic associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743.

4. CDC. Adverse drug events from select medication classes. www.cdc.gov/MedicationSafety/program_focus_activities.html. Accessed August 4, 2014.

5. CDC. Get smart: know when antibiotics work. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/. Accessed August 14, 2014.

Drug store and supermarket shelves display aisle after aisle of OTC medications that alleviate the common symptoms of upper respiratory infections. Despite the easy availability of symptom relief, a significant number of people consult clinicians in primary care offices, emergency departments (EDs), and walk-in or convenient care clinics for help when they feel that they’re “coming down with something.” During these visits, many of these patients expect, and sometimes demand, antibiotics.

Antibiotics may be viewed by the patient as a quick fix, with the demand undoubtedly fueled by busy lifestyles, long work hours, and little time for patients to stay home while ill. Patients so inclined may “doctor shop” if their demands are not met; clinicians know better but may feel pressure to “satisfy the customer” and may rationalize that an antibiotic might prove helpful in a particular case.

Lee et al studied outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTI), including acute nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, influenza, pharyngitis, and sinusitis. In 2000, antibiotics were prescribed during outpatient visits for ARTI to 64% of patients; by 2010, that percentage had increased to 73%.1 Although antibiotics are neither effective nor appropriate for the treatment of ARTI, most of which are viral infections, they are commonly prescribed. Further, while 17% of ARTI prescriptions in 2000 were for broad-spectrum antibiotics, that percentage jumped to 46% in 2010.1,2

Patient insistence on antibiotics may stem either from little knowledge of or little regard for the health problems caused by unnecessary antibiotic use. For example, one study found that 19.3% of drug-related ED visits were related to systemic antibiotics; nearly 80% of those were for allergic reactions.3,4 With an estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions considered inappropriate, the overuse of antibiotics creates unnecessary personal health risks and health care expenditures. Further, a more serious consequence of this overuse is the growing public health problem of antibiotic resistance (see Figure 1).1,2

Clinicians are ideally positioned to address these issues by incorporating effective, proactive strategies into selected patient encounters to specifically explain appropriate versus inappropriate antibiotic use.

Continue for patient handouts >>

One approach is to merge accurate, powerful messages about antibiotics with helpful information about effective OTC products to both enlighten patients and offer them the symptomatic relief they seek. The CDC has taken the lead in this area with its “Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work” initiative, which includes a variety of materials for both health care providers and patients.5

Inspired by the unmet need for written communications that explain viral and bacterial illnesses in simple terms and the reasons why taking antibiotics for the former is a bad idea, we developed two handouts for adult patients who present to the clinician’s office with viral respiratory illnesses.

The first is entitled “Prescription for Recovery From Your Viral Respiratory Illness” [download PDF]. Intended to be duplicated and designed with primary care use in mind, it can be customized for specialty use as well.

This “prescription” handout addresses common complaints of fever, pain (eg, sore throat, body aches, headache), cough, congestion (chest, nose, sinuses), and sneezing/runny nose. Clinicians can check off the appropriate treatments for an individual patient, who can use it as a handy reference to purchase the recommended OTC products and/or for selecting products or preparing helpful remedies at home. Blank lines at the bottom provide space for you to write in your OTC preferences and allow you to customize patient instructions.

The second patient handout is entitled “Antibiotics: When You Need Them, When You Don’t, and What to Take When You Don’t” [download PDF]. This focused patient teaching tool offers an overview of

• Viral and bacterial respiratory illnesses and what the patient should do if he or she has one or the other (including when to see a clinician)

• Some helpful OTC and home treatments for symptoms of viral respiratory illnesses

• When antibiotics are indicated and when they’re not—and why

• The serious problems caused by unnecessary use of antibiotics.

This brief guide can be used as a general informational handout that can, for example, be given, mailed, or e-mailed to all adult patients at the start of cold and flu season and retained by them for reference. It can also be provided along with the “prescription” handout to patients with ARTIs who visit your office. In the latter situation, the patient leaves your office with concrete information and guidance for appropriate care of his or her viral respiratory illness—but without a prescription for antibiotics. As with the “prescription” handout, this brief guide may be duplicated or customized as needed.

To download the handouts: Click here.

REFERENCES

1. Lee GC, Reveles KR, Attridge RT, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing in the United States: 2000-2010. BMC Med. 2014;12:96.

2. CDC. Antibiotics: will they work when you really need them? www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/factsheets/antibiotics.html#MustAct. Accessed August 14, 2014.

3. Shehab N, Patel P, Srinivasan A, Budnitz D. Emergency department visits for antibiotic associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:735-743.

4. CDC. Adverse drug events from select medication classes. www.cdc.gov/MedicationSafety/program_focus_activities.html. Accessed August 4, 2014.

5. CDC. Get smart: know when antibiotics work. www.cdc.gov/getsmart/. Accessed August 14, 2014.