User login

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

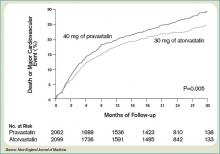

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

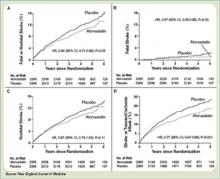

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.

9. Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298-1300.

10. Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253-258.

11. Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Neuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1969-1973.

12. Elkind MS, Sacco RL, MacArthur RB, et al. The neuroprotection with statin therapy for acute recovery trial (NeuSTART): an adaptive design phase I dose-escalation study of high-dose lovastatin in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:210-218.

13. Montaner J, Chacon P, Krupinski J, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J of Neurol. 2008;15:82-90.

14. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20-28.

15. Pitt B, Loscalzo J, Ycas J, Raichlen JS. Lipid levels after acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2008;51:1440-1445.

16. Wiviott SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. A tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials of A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circulation. 2006;113:1406-1414.

17. Elking MS. Statins as acute-stroke treatment. Int J Stroke. 2006;1:224-225.

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.

9. Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298-1300.

10. Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253-258.

11. Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Neuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1969-1973.

12. Elkind MS, Sacco RL, MacArthur RB, et al. The neuroprotection with statin therapy for acute recovery trial (NeuSTART): an adaptive design phase I dose-escalation study of high-dose lovastatin in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:210-218.

13. Montaner J, Chacon P, Krupinski J, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J of Neurol. 2008;15:82-90.

14. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20-28.

15. Pitt B, Loscalzo J, Ycas J, Raichlen JS. Lipid levels after acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2008;51:1440-1445.

16. Wiviott SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. A tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials of A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circulation. 2006;113:1406-1414.

17. Elking MS. Statins as acute-stroke treatment. Int J Stroke. 2006;1:224-225.

Case

A 52-year-old man with no medical history other than a transient ischemic attack (TIA) three months ago presents to the emergency department (ED) following multiple episodes of substernal (ST) chest pressure. He takes no medication. His electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed lateral ST segment depressions, and his cardiac biomarkers were elevated. He underwent cardiac catheterization, and a single drug-eluting stent was successfully placed to a culprit left circumflex lesion. He is now stable less than 24 hours following his initial presentation, without any evidence of heart failure. His providers prescribe aspirin, clopidogrel, metoprolol, and lisinopril. His fasting LDL level is 92 mg/dL.

What, if any, is the role for lipid-lowering therapy at this time?

Overview

Long-term therapy with HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) has been shown through several large, randomized, controlled trials to reduce the risk for death, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke in patients with established coronary disease. The most significant effects were evident after approximately two years of treatment.1,2,3,4

Subsequent trials have shown earlier and more significant reductions in the rates of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events following acute coronary syndromes (ACS) when statins are administered early—within days of the initial event. This is a window of time in which most patients still are hospitalized.4,5,6,7

In addition to this data regarding statin use following ACS, a large, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated similar reductions in the incidence of strokes and cardiovascular events when high-dose atorvastatin was administered within one to six months following TIA or stroke in patients without established coronary disease.8 There is growing data supporting the hypothesis that statins have pleiotropic (non cholesterol-lowering), neuroprotective, properties that may improve patient outcomes following cerebrovascular events.9,10,11 There are ongoing trials investing the role of statins in the acute management of stroke.12,13

Hospitalists frequently manage patients in the stages immediately following ACS and stroke. Based on the large and evolving volume of data regarding the use of statins following these events, when and how should a statin be started in the hospital?

Review of the Data

Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Death and recurrent ischemic events following ACS are most likely to occur in the early phase of recovery. Based on this observation and evidence supporting the early (in some cases within hours of administration) ‘pleiotropic’ or non-cholesterol lowering effects of statins, including improvement in endothelial function and decreases in platelet aggregation, thrombus deposition, and vascular inflammation, the MIRACL study was designed to answer the question of whether the initiation of treatment with a statin within 24 to 96 hours following ACS would reduce the occurrence of death and recurrent ischemia.4,7,14 Investigators randomized 3,086 patients within 24-96 hours (mean 63 hours) following admission for non-ST segment myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (UA) to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators monitored patients for the primary end points of ischemic events (death, non-fatal MI, cardiac arrest with resuscitation, symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence) during a 16-week period. In the treatment arm, the risk of the primary combined end point was significantly reduced—relative risk (RR) 0.84; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.70-1.00; p=0.048. (See Figure 1, pg. 39)

No significant differences were found between atorvastatin and placebo in the risk of death, non-fatal MI, or cardiac arrest with resuscitation. There was, however, a significantly lower risk of recurrent symptomatic myocardial ischemia with objective evidence requiring emergent re-hospitalization in the treatment arm (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; p=0.02). The mean baseline LDL level in the treatment arm was 124 mg/dL, a value that may represent, in part, suppression of the LDL level in the setting of acute ACS. This is a phenomenon previously described in an analysis of the LUNAR trial.15

Suppression of LDL level after ACS appeared to be minimal, however, and is unlikely to be clinically significant. The benefits of atorvastatin in the MIRACL trial did not appear to depend on baseline LDL level—suggesting the decision to initiate statin therapy after ACS should not be influenced by LDL level at the time of the event.

Only one dose of statin was used in the MIRACL trial, and the investigators commented they were unable to determine if a lower dose of atorvastatin or a gradual dose titration to a predetermined LDL target would have achieved similar benefits. The PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial was designed to compare the reductions in death and major cardiovascular events following ACS between LDL lowering to approximately 100 mg/dL using 40 mg/d of pravastatin, and more intensive LDL lowering to approximately 70 mg/dL using 80 mg/d of atorvastatin.5 Investigators enrolled 4,162 patients for a median of seven days following ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, or UA) to the two treatment arms. Investigators observed patients for a period of 18 to 36 months for the primary end points of death, MI, UA, revascularization, and stroke. The median LDL level at the time of enrollment was 106 mg/dL in both treatment arms. During follow up, the median LDL levels achieved were 95 mg/dL in the pravastatin group and 62 mg/dL in the atorvastatin group. After two years, a 16% reduction in the hazard ratio for any primary end point was seen favoring 80 mg/d of atorvastatin—p=0.005; 95% CI=5-26%. (See Figure 2, pg. 39) The benefit of high-dose atorvastatin was seen as early as 30 days after randomization and was sustained throughout the trial.

While the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial supported a specified dosing strategy for statin use following ACS, Phase Z of the A-to-Z trial was designed to evaluate the early initiation of intensive lipid lowering following ACS, as compared to a delayed and less-intensive strategy.5,6 Investigators randomized 4,497 patients (a mean of 3.7 days following either NSTEMI or STEMI) to receive either placebo for four months followed by simvastatin 20 mg/d or simvastatin 40 mg/d for one month followed by simvastatin 80 mg/d. They followed patients for 24 months for the primary end points of cardiovascular death, MI, readmission for ACS, or stroke. The primary end point occurred in 16.7% of the delayed, lower-intensity treatment group and in 14.4% of the early, higher-intensity treatment group (95% CI 0.76-1.04; p=0.14). Despite the lack of a significant difference in the composite primary end point between the two treatment arms, a significant reduction in the secondary end points of cardiovascular mortality (absolute risk reduction (ARR 1.3%; P=0.05) and congestive heart failure (ARR 1.3%; P=0.04) was evident favoring the early, intensive treatment strategy. These differences were not evident until at least four months after randomization. The A-to-Z trial investigators offered several possible explanations for the delay in evident clinical benefits in their trial when compared against the strong trend toward clinical benefit seen with 30 days following the early initiation of high-dose atorvastatin following ACS in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. In the PROVE IT trial, patients were enrolled an average of seven days after their index event, and as a result, 69% had undergone revascularization by this time. In the A-to-Z trial, patients were enrolled an average of three to four days earlier, and, therefore, were less likely to have undergone a revascularization procedure by the time of enrollment—and may have continued on with active thrombotic processes relatively less responsive to statin therapy.6 Another notable difference between PROVE IT and A-to-Z subjects was the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations in the A-to-Z subjects did not differ between treatment groups within 30 days despite significant differences in their LDL levels.16 This lack of a concurrent, pleiotropic, anti-inflammatory effect in the A-to-Z trial aggressive treatment arm may also have contributed to the delayed treatment effect.

In conclusion, the A-to-Z investigators suggest more intensive statin therapy (than the 40 mg Simvastatin in their intensive treatment arm) may be required to derive the most rapid and maximal clinical benefits during the highest risk period immediately following ACS.

Following stroke: Although there is more robust data supporting the benefits of early, intensive, statin therapy following ACS, there also is established and emerging data supporting similar treatment approaches following stroke.

The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) trial was designed to determine whether or not atorvastatin 80 mg daily would reduce the risk of stroke in patients without known coronary heart disease who had suffered a TIA or stroke within the preceding six months.8 Patients who experienced a hemorrhagic or ischemic TIA or stroke between one to six months before study entry were randomized to receive either atorvastatin 80 mg/d or placebo.

Investigators followed patients for a mean period of 4.9 years for the primary end point of time to non-fatal or fatal stroke. Secondary composite end points included stroke or TIA, and any coronary or peripheral arterial event, including death from cardiac causes, non-fatal MI, ACS, revascularization (coronary, carotid, peripheral), and death from any cause. No difference in mean baseline LDL levels was witnessed between the treatment and placebo arms (132.7 and 133.7 mg/dL, respectively). Atorvastatin was associated with a 16% relative reduction in the risk of stroke—hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI 0.71–0.99; p=0.03. This was found despite an increase in hemorrhagic stroke in the atorvastatin group—a finding that supports an epidemiologic association between low cholesterol levels and brain hemorrhage. The risk of cardiovascular events also was significantly reduced, however, no significant difference in overall mortality was observed between the two groups.

In conclusion, the authors recommend the initiation of high-dose atorvastatin “soon” after stroke or TIA. One can only conclude, based on these data, statin therapy should be initiated within six months of TIA or stroke, in accordance with the study design. There is retrospective data suggesting benefit to statin therapy initiated within four weeks following ischemic stroke, and there are prospective trials in process evaluating the potential benefits of statins initiated within 24 hours following ischemic stroke, however, no large, randomized, controlled trial can demonstrate the effect of statins when used as acute stroke therapy.9,12,13,17

Back to the Case

The patient described in our case has a history of TIA and experienced an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI) within the preceding 24 hours. He underwent a revascularization procedure (PCI with stent), and is on appropriate therapy, including dual anti-platelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, a beta-blocker, and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Based on the data and conclusions of the MIRACL, PROVE IT-TIMI 22, and SPARCL trials, high-dose statin therapy with atorvastatin 80 mg/d should be initiated immediately in the patient in order to significantly reduce his risk of recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events and stroke following his acute coronary syndrome and TIA.

Bottom Line

Following ACS, high-dose statin therapy with 80 mg of atorvastatin per day should be initiated when the patient is still in the hospital, irrespective of baseline LDL level. Statin therapy should also strongly be considered for secondary stroke prevention in most patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. TH

Caleb Hale, MD, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Joseph Ming Wah Li is director of the hospital medicine program and associate chief, division of general medicine and primary care at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, and assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

References

1. Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994;344:1383-1389.

2. Sacks RM, Pfeffer MA, Moye LA, et al. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1001-1009.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes. The MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711-1718.

5. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495-1504.

6. Lemos JA, Blazing MA, Wiviott SD, et al. Early intensive vs. a delayed conservative simvastatin strategy in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Phase Z of the A to Z trial. JAMA. 2004;292:1307-1316.

7. Waters D, Schwartz GG, Olsson AG. The myocardial ischemia reduction with acute cholesterol lowering (MIRACL) trial: a new frontier for statins? Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2001;2;111-114.

8. The Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549-559.

9. Moonis M, Kane K, Schwiderski U, Sandage BW, Fisher M. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors improve acute ischemic stroke outcome. Stroke. 2005;36:1298-1300.

10. Elkind MS, Flint AC, Sciacca RR, Sacco RL. Lipid-lowering agent use at ischemic stroke onset is associated with decreased mortality. Neurology. 2005;65:253-258.

11. Vaughan CJ, Delanty N. Neuroprotective properties of statins in cerebral ischemia and stroke. Stroke. 1999;30:1969-1973.

12. Elkind MS, Sacco RL, MacArthur RB, et al. The neuroprotection with statin therapy for acute recovery trial (NeuSTART): an adaptive design phase I dose-escalation study of high-dose lovastatin in acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:210-218.

13. Montaner J, Chacon P, Krupinski J, et al. Simvastatin in the acute phase of ischemic stroke: a safety and efficacy pilot trial. Eur J of Neurol. 2008;15:82-90.

14. Ridker PM, Cannon CP, Morrow D, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:20-28.

15. Pitt B, Loscalzo J, Ycas J, Raichlen JS. Lipid levels after acute coronary syndromes. JACC. 2008;51:1440-1445.

16. Wiviott SD, de Lemos JA, Cannon CP, et al. A tale of two trials: a comparison of the post-acute coronary syndrome lipid-lowering trials of A to Z and PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Circulation. 2006;113:1406-1414.

17. Elking MS. Statins as acute-stroke treatment. Int J Stroke. 2006;1:224-225.