User login

New PCNSL guidelines emphasize importance of patient fitness

New guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) emphasize prompt diagnosis, aggressive treatment whenever possible, and multidisciplinary team support.

A unique aspect for hematologic cancers, the guidelines note, is that appropriate treatment for PCNSL requires input from neurology specialists.

And the guidelines recommend methotrexate-based treatment only be administered at centers experienced in delivering intensive chemotherapy.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust in Nottingham, U.K., and his colleagues on behalf of the British Society for Haematology published the guidelines in BJH.

The authors incorporated findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guidelines were issued more than a decade ago.

The new guidelines provide recommendations for diagnosis and imaging, primary treatment of PCNSL, consolidation chemotherapy, follow-up, management of relapsed/refractory disease, and neuropsychological assessments.

Highlights include:

- People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists

- Histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings should be performed

- Corticosteroids should be avoided or discontinued before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis

- Aggressive induction treatment should be chosen based on the patient’s fitness

- Patients should be offered entry into clinical trials whenever possible

- Universal screening for eye involvement should be conducted.

Primary treatment

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL—induction of remission followed by consolidation—should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis, and a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age.

The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immuno-chemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)—optimally, four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab.

Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab, and procarbazine, the guidelines say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy, whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), or corticosteroids may be used.

The authors do not recommend intrathecal chemotherapy alongside systemic CNS-directed therapy.

Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) routinely after every two cycles of HD-MTX-based therapy and at the end of remission induction.

Consolidation chemotherapy

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with non-progressive disease. High-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is the recommended first-line option for consolidation.

Patients ineligible for high-dose therapy followed by ASCT who have residual disease after induction therapy should be considered for WBRT. This is also the case for patients with residual disease after thiotepa-based ASCT.

However, Dr. Fox and his colleagues say WBRT consolidation is “contentious” for patients in complete response after HD-MTX regimens but ineligible for ASCT. The authors suggest carefully balancing potential improvement in progression-free survival against risks of neurocognitive toxicity.

Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency—the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options—and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

Some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne and/or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

New guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) emphasize prompt diagnosis, aggressive treatment whenever possible, and multidisciplinary team support.

A unique aspect for hematologic cancers, the guidelines note, is that appropriate treatment for PCNSL requires input from neurology specialists.

And the guidelines recommend methotrexate-based treatment only be administered at centers experienced in delivering intensive chemotherapy.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust in Nottingham, U.K., and his colleagues on behalf of the British Society for Haematology published the guidelines in BJH.

The authors incorporated findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guidelines were issued more than a decade ago.

The new guidelines provide recommendations for diagnosis and imaging, primary treatment of PCNSL, consolidation chemotherapy, follow-up, management of relapsed/refractory disease, and neuropsychological assessments.

Highlights include:

- People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists

- Histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings should be performed

- Corticosteroids should be avoided or discontinued before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis

- Aggressive induction treatment should be chosen based on the patient’s fitness

- Patients should be offered entry into clinical trials whenever possible

- Universal screening for eye involvement should be conducted.

Primary treatment

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL—induction of remission followed by consolidation—should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis, and a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age.

The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immuno-chemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)—optimally, four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab.

Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab, and procarbazine, the guidelines say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy, whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), or corticosteroids may be used.

The authors do not recommend intrathecal chemotherapy alongside systemic CNS-directed therapy.

Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) routinely after every two cycles of HD-MTX-based therapy and at the end of remission induction.

Consolidation chemotherapy

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with non-progressive disease. High-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is the recommended first-line option for consolidation.

Patients ineligible for high-dose therapy followed by ASCT who have residual disease after induction therapy should be considered for WBRT. This is also the case for patients with residual disease after thiotepa-based ASCT.

However, Dr. Fox and his colleagues say WBRT consolidation is “contentious” for patients in complete response after HD-MTX regimens but ineligible for ASCT. The authors suggest carefully balancing potential improvement in progression-free survival against risks of neurocognitive toxicity.

Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency—the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options—and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

Some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne and/or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

New guidelines on the diagnosis and management of patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) emphasize prompt diagnosis, aggressive treatment whenever possible, and multidisciplinary team support.

A unique aspect for hematologic cancers, the guidelines note, is that appropriate treatment for PCNSL requires input from neurology specialists.

And the guidelines recommend methotrexate-based treatment only be administered at centers experienced in delivering intensive chemotherapy.

Christopher P. Fox, MD, of the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust in Nottingham, U.K., and his colleagues on behalf of the British Society for Haematology published the guidelines in BJH.

The authors incorporated findings from studies published since the society’s last comprehensive PCNSL guidelines were issued more than a decade ago.

The new guidelines provide recommendations for diagnosis and imaging, primary treatment of PCNSL, consolidation chemotherapy, follow-up, management of relapsed/refractory disease, and neuropsychological assessments.

Highlights include:

- People with suspected PCNSL must receive quick and coordinated attention from a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, hematologist-oncologists, and ocular specialists

- Histological diagnoses in addition to imaging findings should be performed

- Corticosteroids should be avoided or discontinued before biopsy, as even a short course of steroids can impede diagnosis

- Aggressive induction treatment should be chosen based on the patient’s fitness

- Patients should be offered entry into clinical trials whenever possible

- Universal screening for eye involvement should be conducted.

Primary treatment

Dr. Fox and his colleagues say definitive treatment for PCNSL—induction of remission followed by consolidation—should start within 2 weeks of diagnosis, and a treatment regimen should be chosen according to a patient’s physiological fitness, not age.

The fittest patients, who have better organ function and fewer comorbidities, should be eligible for intensive combination immuno-chemotherapy incorporating high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)—optimally, four cycles of HD-MTX, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab.

Those deemed unfit for this regimen should be offered induction treatment with HD-MTX, rituximab, and procarbazine, the guidelines say.

If patients cannot tolerate HD-MTX, oral chemotherapy, whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT), or corticosteroids may be used.

The authors do not recommend intrathecal chemotherapy alongside systemic CNS-directed therapy.

Response should be assessed with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) routinely after every two cycles of HD-MTX-based therapy and at the end of remission induction.

Consolidation chemotherapy

Consolidation therapy should be initiated after induction for all patients with non-progressive disease. High-dose thiotepa-based chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) is the recommended first-line option for consolidation.

Patients ineligible for high-dose therapy followed by ASCT who have residual disease after induction therapy should be considered for WBRT. This is also the case for patients with residual disease after thiotepa-based ASCT.

However, Dr. Fox and his colleagues say WBRT consolidation is “contentious” for patients in complete response after HD-MTX regimens but ineligible for ASCT. The authors suggest carefully balancing potential improvement in progression-free survival against risks of neurocognitive toxicity.

Response to consolidation, again measured with contrast-enhanced MRI, should be carried out between 1 and 2 months after therapy is completed, and patients should be referred for neuropsychological testing to assess cognitive function.

Patients with relapsed or refractory disease should be approached with maximum urgency—the guidelines offer an algorithm for retreatment options—and offered clinical trial entry wherever possible.

Some coauthors, including the lead author, disclosed receiving fees from pharmaceutical manufacturers Adienne and/or F. Hoffman-La Roche.

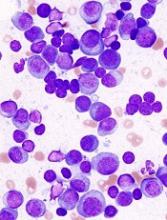

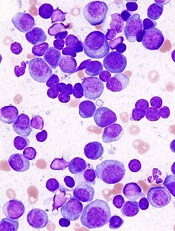

Study reveals long-term survival in MM patients

A retrospective study suggests one in seven patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) who are eligible for transplant may live at least as long as similar individuals in the general population.

The study included more than 7,000 MM patients, and 14.3% of those patients were able to meet or exceed their expected survival based on data from matched subjects in the general population.

Researchers believe that figure may be even higher today, as more than 90% of patients in this study were treated in the era before novel therapies became available.

Saad Z. Usmani, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute/Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina, and his colleagues described this study in Blood Cancer Journal.

The researchers studied 7,291 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were up to 75 years old and eligible for treatment with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant. The patients were treated on clinical trials in 10 countries.

Factors associated with survival

Patients who had achieved a complete response (CR) 1 year after diagnosis had better median progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who did not achieve a CR—3.3 years and 2.6 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

Patients with a CR also had better median overall survival (OS)—8.5 years and 6.3 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

The identification of early CR as a predictor of PFS and OS “underscores the importance of depth of response as we explore novel regimens for newly diagnosed MM along with MRD [minimal residual disease] endpoints,” Dr. Usmani and his colleagues wrote.

They did acknowledge, however, that the patients studied were a selected group eligible for transplant and treated on trials.

Dr. Usmani and his colleagues also performed multivariate analyses to assess clinical variables at diagnosis associated with 10-year survival as compared with 2-year death. The results indicated that patients were less likely to be alive at 10 years if they:

- Were older than 65 (odds ratio [OR]for death, 1.87, P=0.002)

- Had an IgA isotype (OR=1.53; P=0.004)

- Had an albumin level lower than 3.5 g/dL (OR=1.36; P=0.023)

- Had a beta-2 microglobulin level of at least 3.5 mg/dL (OR=1.86; P<0.001)

- Had a serum creatinine level of at least 2 mg/dL (OR=1.77; P=0.005)

- Had a hemoglobin level below 10 g/dL (OR=1.55; P=0.003)

- Had a platelet count below 150,000/μL (OR=2.26; P<0.001).

Cytogenetic abnormalities did not independently predict long-term survival, but these abnormalities were obtained only by conventional band karyotyping and were not available for some patients.

Comparison to general population

Overall, the MM patients had a relative survival of about 0.9 compared with the matched general population. Relative survival was the ratio of observed survival among MM patients to expected survival in a population with comparable characteristics, such as nationality, age, and sex.

With follow-up out to about 20 years, the cure fraction—or the proportion of patients achieving or exceeding expected survival compared with the matched general population—was 14.3%.

The researchers noted that recent therapeutic advances “have re-ignited the debate on possible functional curability of a subset of MM patients. [T]here are perhaps more effective drugs and drug classes in the clinician’s armamentarium than [were] available for MM patients being treated in the 1990s or even early 2000s.”

“This may mean that the depth of response after induction therapy may continue to improve over time, potentially further improving the PFS/OS of [the] biologic subset who previously achieved [a partial response] yet had good long-term survival.”

Dr. Usmani reported relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, Sanofi, SkylineDx, Array Biopharma, and Pharmacyclics.

A retrospective study suggests one in seven patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) who are eligible for transplant may live at least as long as similar individuals in the general population.

The study included more than 7,000 MM patients, and 14.3% of those patients were able to meet or exceed their expected survival based on data from matched subjects in the general population.

Researchers believe that figure may be even higher today, as more than 90% of patients in this study were treated in the era before novel therapies became available.

Saad Z. Usmani, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute/Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina, and his colleagues described this study in Blood Cancer Journal.

The researchers studied 7,291 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were up to 75 years old and eligible for treatment with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant. The patients were treated on clinical trials in 10 countries.

Factors associated with survival

Patients who had achieved a complete response (CR) 1 year after diagnosis had better median progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who did not achieve a CR—3.3 years and 2.6 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

Patients with a CR also had better median overall survival (OS)—8.5 years and 6.3 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

The identification of early CR as a predictor of PFS and OS “underscores the importance of depth of response as we explore novel regimens for newly diagnosed MM along with MRD [minimal residual disease] endpoints,” Dr. Usmani and his colleagues wrote.

They did acknowledge, however, that the patients studied were a selected group eligible for transplant and treated on trials.

Dr. Usmani and his colleagues also performed multivariate analyses to assess clinical variables at diagnosis associated with 10-year survival as compared with 2-year death. The results indicated that patients were less likely to be alive at 10 years if they:

- Were older than 65 (odds ratio [OR]for death, 1.87, P=0.002)

- Had an IgA isotype (OR=1.53; P=0.004)

- Had an albumin level lower than 3.5 g/dL (OR=1.36; P=0.023)

- Had a beta-2 microglobulin level of at least 3.5 mg/dL (OR=1.86; P<0.001)

- Had a serum creatinine level of at least 2 mg/dL (OR=1.77; P=0.005)

- Had a hemoglobin level below 10 g/dL (OR=1.55; P=0.003)

- Had a platelet count below 150,000/μL (OR=2.26; P<0.001).

Cytogenetic abnormalities did not independently predict long-term survival, but these abnormalities were obtained only by conventional band karyotyping and were not available for some patients.

Comparison to general population

Overall, the MM patients had a relative survival of about 0.9 compared with the matched general population. Relative survival was the ratio of observed survival among MM patients to expected survival in a population with comparable characteristics, such as nationality, age, and sex.

With follow-up out to about 20 years, the cure fraction—or the proportion of patients achieving or exceeding expected survival compared with the matched general population—was 14.3%.

The researchers noted that recent therapeutic advances “have re-ignited the debate on possible functional curability of a subset of MM patients. [T]here are perhaps more effective drugs and drug classes in the clinician’s armamentarium than [were] available for MM patients being treated in the 1990s or even early 2000s.”

“This may mean that the depth of response after induction therapy may continue to improve over time, potentially further improving the PFS/OS of [the] biologic subset who previously achieved [a partial response] yet had good long-term survival.”

Dr. Usmani reported relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, Sanofi, SkylineDx, Array Biopharma, and Pharmacyclics.

A retrospective study suggests one in seven patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) who are eligible for transplant may live at least as long as similar individuals in the general population.

The study included more than 7,000 MM patients, and 14.3% of those patients were able to meet or exceed their expected survival based on data from matched subjects in the general population.

Researchers believe that figure may be even higher today, as more than 90% of patients in this study were treated in the era before novel therapies became available.

Saad Z. Usmani, MD, of the Levine Cancer Institute/Atrium Health in Charlotte, North Carolina, and his colleagues described this study in Blood Cancer Journal.

The researchers studied 7,291 patients with newly diagnosed MM who were up to 75 years old and eligible for treatment with high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant. The patients were treated on clinical trials in 10 countries.

Factors associated with survival

Patients who had achieved a complete response (CR) 1 year after diagnosis had better median progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who did not achieve a CR—3.3 years and 2.6 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

Patients with a CR also had better median overall survival (OS)—8.5 years and 6.3 years, respectively (P<0.0001).

The identification of early CR as a predictor of PFS and OS “underscores the importance of depth of response as we explore novel regimens for newly diagnosed MM along with MRD [minimal residual disease] endpoints,” Dr. Usmani and his colleagues wrote.

They did acknowledge, however, that the patients studied were a selected group eligible for transplant and treated on trials.

Dr. Usmani and his colleagues also performed multivariate analyses to assess clinical variables at diagnosis associated with 10-year survival as compared with 2-year death. The results indicated that patients were less likely to be alive at 10 years if they:

- Were older than 65 (odds ratio [OR]for death, 1.87, P=0.002)

- Had an IgA isotype (OR=1.53; P=0.004)

- Had an albumin level lower than 3.5 g/dL (OR=1.36; P=0.023)

- Had a beta-2 microglobulin level of at least 3.5 mg/dL (OR=1.86; P<0.001)

- Had a serum creatinine level of at least 2 mg/dL (OR=1.77; P=0.005)

- Had a hemoglobin level below 10 g/dL (OR=1.55; P=0.003)

- Had a platelet count below 150,000/μL (OR=2.26; P<0.001).

Cytogenetic abnormalities did not independently predict long-term survival, but these abnormalities were obtained only by conventional band karyotyping and were not available for some patients.

Comparison to general population

Overall, the MM patients had a relative survival of about 0.9 compared with the matched general population. Relative survival was the ratio of observed survival among MM patients to expected survival in a population with comparable characteristics, such as nationality, age, and sex.

With follow-up out to about 20 years, the cure fraction—or the proportion of patients achieving or exceeding expected survival compared with the matched general population—was 14.3%.

The researchers noted that recent therapeutic advances “have re-ignited the debate on possible functional curability of a subset of MM patients. [T]here are perhaps more effective drugs and drug classes in the clinician’s armamentarium than [were] available for MM patients being treated in the 1990s or even early 2000s.”

“This may mean that the depth of response after induction therapy may continue to improve over time, potentially further improving the PFS/OS of [the] biologic subset who previously achieved [a partial response] yet had good long-term survival.”

Dr. Usmani reported relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Takeda, Sanofi, SkylineDx, Array Biopharma, and Pharmacyclics.

The case for longer treatment in MM: Part 1

In Part 1 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, describes the benefits of longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Despite recent progress in advancing the care of patients with multiple myeloma (MM), this cancer remains incurable.

Although novel combination regimens have driven major improvements in patient outcomes, most MM patients still experience multiple relapses, even those who respond to treatment initially.1

Historically, MM was treated for a fixed duration, followed by a treatment-free interval and additional treatment at relapse. However, evidence suggests that continuous therapy after an initial response may be a better approach.2,3

Pooled data from three large, phase 3 trials in newly diagnosed MM patients suggest that continuous therapy may lead to an increase in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).2

These results are supported by a meta-analysis, which showed favorable outcomes in PFS and OS with lenalidomide maintenance compared to placebo or observation in newly diagnosed MM patients who had received high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.3

Given these emerging findings and the availability of effective and tolerable therapies suitable for longer use, there is an opportunity to increase the adoption of this treatment strategy to improve outcomes for MM patients.

The concept of longer treatment for MM is not new. The first clinical trials in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of this approach were conducted 40 years ago in patients initially treated with melphalan and prednisone. However, modest efficacy and substantial toxicity limited longer treatment with those agents.4-7

The intervening years saw the introduction of new agents with different mechanisms of action, such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulators. These therapies, commonly used as initial treatment, provided physicians with additional options for treating patients longer.

Research has shown that longer treatment with immunomodulatory agents and proteasome inhibitors can be clinically effective.8

Longer treatment—integrated in the first-line treatment strategy and before a patient relapses—may enhance conventional induction strategies, resulting in better PFS and OS.9,10

Continuous treatment, in which a patient receives treatment beyond a fixed induction period, has demonstrated extended PFS and OS as well.2,3

Data supporting the benefits of prolonged therapy with immunomodulatory drugs has been a key driver behind the shifting paradigm in favor of longer treatment as the standard of care.11,3

Additionally, continuing treatment with a proteasome inhibitor beyond induction therapy is associated with an improvement in the depth of response and prolonged OS.12

Longer treatment with proteasome inhibitors is also associated with deepening response rates and improved PFS following hematopoietic stem cell transplant.13-15

Recent research has also shown that patients may achieve deeper remission with longer treatment,16,17 overturning the long-held belief that longer duration of therapy can only extend a response rather than improve it.

Moreover, treating patients for longer may now be possible because of the favorable toxicity profile of some of the novel therapies currently available, which have fewer cumulative or late-onset toxicities.18

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lonial S. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010; 2010:303-9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.303

2. Palumbo A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33(30):3459-66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2466

3. McCarthy PL et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35(29):3279-3289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6679

4. Joks M et al. Eur J Haematol. 2015 ;94(2):109-14. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12412

5. Berenson JR et al. Blood. 2002; 99:3163-8. doi: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/99/9/3163.long

6. Shustik C et al. Br J Haematol. 2007; 126:201-11. doi: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06405.x

7. Fritz E, Ludwig H. Ann Oncol. 2000 Nov;11(11):1427-36

8. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119:3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

9. Mateos MV et al. Am J Hematol. 2015; 90(4):314-9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23933

10. Benboubker L et al. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(10):906-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402551

11. Holstein SA et al. Lancet Haematol. 2017; 4(9):e431-e442. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30140-0

12. Mateos MV et al. Blood. 2014; 124:1887-1893. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-573733

13. Sonneveld P et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2010;116. Abstract 40

14. Rosiñol L et al. Blood. 2012; 120(8):1589-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-02-408922

15. Richardson PG et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352(24):2487-98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445

16. de Tute RM et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2017; 130: 904. Abstract 904

17. Dimopoulos M et al. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0583-7

18. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

In Part 1 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, describes the benefits of longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Despite recent progress in advancing the care of patients with multiple myeloma (MM), this cancer remains incurable.

Although novel combination regimens have driven major improvements in patient outcomes, most MM patients still experience multiple relapses, even those who respond to treatment initially.1

Historically, MM was treated for a fixed duration, followed by a treatment-free interval and additional treatment at relapse. However, evidence suggests that continuous therapy after an initial response may be a better approach.2,3

Pooled data from three large, phase 3 trials in newly diagnosed MM patients suggest that continuous therapy may lead to an increase in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).2

These results are supported by a meta-analysis, which showed favorable outcomes in PFS and OS with lenalidomide maintenance compared to placebo or observation in newly diagnosed MM patients who had received high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.3

Given these emerging findings and the availability of effective and tolerable therapies suitable for longer use, there is an opportunity to increase the adoption of this treatment strategy to improve outcomes for MM patients.

The concept of longer treatment for MM is not new. The first clinical trials in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of this approach were conducted 40 years ago in patients initially treated with melphalan and prednisone. However, modest efficacy and substantial toxicity limited longer treatment with those agents.4-7

The intervening years saw the introduction of new agents with different mechanisms of action, such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulators. These therapies, commonly used as initial treatment, provided physicians with additional options for treating patients longer.

Research has shown that longer treatment with immunomodulatory agents and proteasome inhibitors can be clinically effective.8

Longer treatment—integrated in the first-line treatment strategy and before a patient relapses—may enhance conventional induction strategies, resulting in better PFS and OS.9,10

Continuous treatment, in which a patient receives treatment beyond a fixed induction period, has demonstrated extended PFS and OS as well.2,3

Data supporting the benefits of prolonged therapy with immunomodulatory drugs has been a key driver behind the shifting paradigm in favor of longer treatment as the standard of care.11,3

Additionally, continuing treatment with a proteasome inhibitor beyond induction therapy is associated with an improvement in the depth of response and prolonged OS.12

Longer treatment with proteasome inhibitors is also associated with deepening response rates and improved PFS following hematopoietic stem cell transplant.13-15

Recent research has also shown that patients may achieve deeper remission with longer treatment,16,17 overturning the long-held belief that longer duration of therapy can only extend a response rather than improve it.

Moreover, treating patients for longer may now be possible because of the favorable toxicity profile of some of the novel therapies currently available, which have fewer cumulative or late-onset toxicities.18

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lonial S. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010; 2010:303-9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.303

2. Palumbo A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33(30):3459-66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2466

3. McCarthy PL et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35(29):3279-3289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6679

4. Joks M et al. Eur J Haematol. 2015 ;94(2):109-14. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12412

5. Berenson JR et al. Blood. 2002; 99:3163-8. doi: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/99/9/3163.long

6. Shustik C et al. Br J Haematol. 2007; 126:201-11. doi: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06405.x

7. Fritz E, Ludwig H. Ann Oncol. 2000 Nov;11(11):1427-36

8. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119:3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

9. Mateos MV et al. Am J Hematol. 2015; 90(4):314-9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23933

10. Benboubker L et al. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(10):906-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402551

11. Holstein SA et al. Lancet Haematol. 2017; 4(9):e431-e442. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30140-0

12. Mateos MV et al. Blood. 2014; 124:1887-1893. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-573733

13. Sonneveld P et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2010;116. Abstract 40

14. Rosiñol L et al. Blood. 2012; 120(8):1589-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-02-408922

15. Richardson PG et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352(24):2487-98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445

16. de Tute RM et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2017; 130: 904. Abstract 904

17. Dimopoulos M et al. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0583-7

18. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

In Part 1 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, describes the benefits of longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Despite recent progress in advancing the care of patients with multiple myeloma (MM), this cancer remains incurable.

Although novel combination regimens have driven major improvements in patient outcomes, most MM patients still experience multiple relapses, even those who respond to treatment initially.1

Historically, MM was treated for a fixed duration, followed by a treatment-free interval and additional treatment at relapse. However, evidence suggests that continuous therapy after an initial response may be a better approach.2,3

Pooled data from three large, phase 3 trials in newly diagnosed MM patients suggest that continuous therapy may lead to an increase in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).2

These results are supported by a meta-analysis, which showed favorable outcomes in PFS and OS with lenalidomide maintenance compared to placebo or observation in newly diagnosed MM patients who had received high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplant.3

Given these emerging findings and the availability of effective and tolerable therapies suitable for longer use, there is an opportunity to increase the adoption of this treatment strategy to improve outcomes for MM patients.

The concept of longer treatment for MM is not new. The first clinical trials in which researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of this approach were conducted 40 years ago in patients initially treated with melphalan and prednisone. However, modest efficacy and substantial toxicity limited longer treatment with those agents.4-7

The intervening years saw the introduction of new agents with different mechanisms of action, such as proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulators. These therapies, commonly used as initial treatment, provided physicians with additional options for treating patients longer.

Research has shown that longer treatment with immunomodulatory agents and proteasome inhibitors can be clinically effective.8

Longer treatment—integrated in the first-line treatment strategy and before a patient relapses—may enhance conventional induction strategies, resulting in better PFS and OS.9,10

Continuous treatment, in which a patient receives treatment beyond a fixed induction period, has demonstrated extended PFS and OS as well.2,3

Data supporting the benefits of prolonged therapy with immunomodulatory drugs has been a key driver behind the shifting paradigm in favor of longer treatment as the standard of care.11,3

Additionally, continuing treatment with a proteasome inhibitor beyond induction therapy is associated with an improvement in the depth of response and prolonged OS.12

Longer treatment with proteasome inhibitors is also associated with deepening response rates and improved PFS following hematopoietic stem cell transplant.13-15

Recent research has also shown that patients may achieve deeper remission with longer treatment,16,17 overturning the long-held belief that longer duration of therapy can only extend a response rather than improve it.

Moreover, treating patients for longer may now be possible because of the favorable toxicity profile of some of the novel therapies currently available, which have fewer cumulative or late-onset toxicities.18

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lonial S. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010; 2010:303-9. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.303

2. Palumbo A et al. J Clin Oncol. 2015; 33(30):3459-66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2466

3. McCarthy PL et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35(29):3279-3289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.6679

4. Joks M et al. Eur J Haematol. 2015 ;94(2):109-14. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12412

5. Berenson JR et al. Blood. 2002; 99:3163-8. doi: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/99/9/3163.long

6. Shustik C et al. Br J Haematol. 2007; 126:201-11. doi: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06405.x

7. Fritz E, Ludwig H. Ann Oncol. 2000 Nov;11(11):1427-36

8. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119:3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

9. Mateos MV et al. Am J Hematol. 2015; 90(4):314-9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23933

10. Benboubker L et al. N Engl J Med. 2014; 371(10):906-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402551

11. Holstein SA et al. Lancet Haematol. 2017; 4(9):e431-e442. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30140-0

12. Mateos MV et al. Blood. 2014; 124:1887-1893. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-05-573733

13. Sonneveld P et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2010;116. Abstract 40

14. Rosiñol L et al. Blood. 2012; 120(8):1589-96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-02-408922

15. Richardson PG et al. N Engl J Med. 2005; 352(24):2487-98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445

16. de Tute RM et al. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood. 2017; 130: 904. Abstract 904

17. Dimopoulos M et al. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0583-7

18. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

The case for longer treatment in MM: Part 2

In Part 2 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, addresses the barriers to longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Attitudes regarding longer treatment can present barriers to widespread adoption of this approach in multiple myeloma (MM).

Indeed, some clinicians continue to follow a fixed-duration approach to treatment in MM, only considering further treatment once the patient has relapsed rather than treating the patient until disease progression.

In the MM community, some are reluctant to adopt a strategy of treating longer because of the modest efficacy gains observed with early research or concern over tolerability issues, including the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy or secondary malignancies.1

Others are uncertain about the optimal duration of therapy or the selection of an agent that will balance any potential gain in depth of response with the risk of late-onset or cumulative toxicities.

The potentially high cost of longer treatment for patients, their families, and/or the healthcare system overall also presents a challenge.

It is feasible that treating patients for longer may drive up healthcare utilization and take a toll on patients and caregivers, who may incur out-of-pocket costs because of the need to travel to a hospital or doctor’s office for intravenous therapies, requiring them to miss work.2

It is important to recognize, however, that more convenient all-oral treatment regimens are now available that do not require infusion at a hospital or clinic. Furthermore, results from recent studies suggest the majority of cancer patients prefer oral over intravenous therapies, which could reduce non-pharmacy healthcare costs.3,4

Healthcare providers might be more likely to accept and adopt a longer treatment approach for MM if they had access to data describing the optimal duration, dosage, schedule, toxicity, and quality of life standards.

Ongoing, randomized, phase 3 trials are evaluating the benefits of treating longer with an oral proteasome inhibitor in patients with newly diagnosed MM.5,6

Updated treatment guidelines and consensus statements will provide further guidance for clinicians on the benefits of maintenance therapy in both transplant-eligible and -ineligible patients with newly diagnosed MM.

The recently updated MM guidelines from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend longer treatment or maintenance therapy in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).7

Based on evidence from studies such as FIRST and SWOG S0777, ESMO also recommends continuous treatment or treatment until progression with lenalidomide-dexamethasone and bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who are ineligible for HSCT.7-9

As there is no one-size-fits-all treatment approach in MM, a personalized treatment plan should be designed for each patient. This plan should take into account a number of factors, including age, disease characteristics, performance status, treatment history, and the patient’s goals of care and personal preferences.10

If the patient is a candidate for longer treatment, the clinician should carefully weigh the potential impact on disease-free and overall survival against the potential side effects, as well as assess the patient’s likelihood of adhering to the medication.

With the availability of newer, less-toxic medications that can be tolerated for a greater duration and are easy to administer, aiding in overall treatment compliance, sustained remissions are possible.11-13

Forty years ago, MM patients had very few treatment options, and the 5-year survival rate was 26%.14

Since then, novel therapies, including proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, have replaced conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, leading to major improvements in survival.15,16

With emerging research that supports the value of longer treatment strategies for both patients and the healthcare system, clinicians will have a proven strategy to help their patients attain long-term disease control while maintaining quality of life.2, 17-19

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

2. Goodwin J et al. Cancer Nurs. 2013; 36(4):301-8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182693522

3. Eek D et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016; 10:1609-21. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106629

4. Bauer S et al. Value in Health. 2017; 20: A451. Abstract PCN217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.299

5. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Citrate (MLN9708) Maintenance Therapy in Participants With Multiple Myeloma Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02181413 (Identification No. NCT02181413).

6. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Not Treated With Stem Cell Transplantation. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02312258 (Identification No. NCT02312258).

7. Moreau P et al. Ann Oncol. 2017; 28: iv52-iv61. doi: https://org/10.1093/annonc/mdx096

8. Facon T et al. Blood. 2018131(3):301-310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795047

9. Durie BG et al. Lancet. 2017; 389(10068):519-527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X.

10. Laubach J et al. Leukemia. 2016; 30(5):1005-17. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.356

11. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119: 3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

12. Lehners N et al. Cancer Med. 2018; 7(2): 307–316. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1283

13. Attal M et al. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1872-1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114138

14. National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed March 28, 2018.

15. Kumar SK et al. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2516-20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

16. Fonseca R et al. Leukemia. 2017 Sep;31(9):1915-1921. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.380

17. Palumbo A, Niesvizky R. Leuk Res. 2012; 36 Suppl 1:S19-26. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(12)70005-X

18. Girnius S, Munshi NC. Leuk Suppl. 2013; 2(Suppl 1): S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/leusup.2013.2

19. Mateos M-V, San Miguel JF. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013; 2013:488-95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.488

In Part 2 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, addresses the barriers to longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Attitudes regarding longer treatment can present barriers to widespread adoption of this approach in multiple myeloma (MM).

Indeed, some clinicians continue to follow a fixed-duration approach to treatment in MM, only considering further treatment once the patient has relapsed rather than treating the patient until disease progression.

In the MM community, some are reluctant to adopt a strategy of treating longer because of the modest efficacy gains observed with early research or concern over tolerability issues, including the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy or secondary malignancies.1

Others are uncertain about the optimal duration of therapy or the selection of an agent that will balance any potential gain in depth of response with the risk of late-onset or cumulative toxicities.

The potentially high cost of longer treatment for patients, their families, and/or the healthcare system overall also presents a challenge.

It is feasible that treating patients for longer may drive up healthcare utilization and take a toll on patients and caregivers, who may incur out-of-pocket costs because of the need to travel to a hospital or doctor’s office for intravenous therapies, requiring them to miss work.2

It is important to recognize, however, that more convenient all-oral treatment regimens are now available that do not require infusion at a hospital or clinic. Furthermore, results from recent studies suggest the majority of cancer patients prefer oral over intravenous therapies, which could reduce non-pharmacy healthcare costs.3,4

Healthcare providers might be more likely to accept and adopt a longer treatment approach for MM if they had access to data describing the optimal duration, dosage, schedule, toxicity, and quality of life standards.

Ongoing, randomized, phase 3 trials are evaluating the benefits of treating longer with an oral proteasome inhibitor in patients with newly diagnosed MM.5,6

Updated treatment guidelines and consensus statements will provide further guidance for clinicians on the benefits of maintenance therapy in both transplant-eligible and -ineligible patients with newly diagnosed MM.

The recently updated MM guidelines from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend longer treatment or maintenance therapy in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).7

Based on evidence from studies such as FIRST and SWOG S0777, ESMO also recommends continuous treatment or treatment until progression with lenalidomide-dexamethasone and bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who are ineligible for HSCT.7-9

As there is no one-size-fits-all treatment approach in MM, a personalized treatment plan should be designed for each patient. This plan should take into account a number of factors, including age, disease characteristics, performance status, treatment history, and the patient’s goals of care and personal preferences.10

If the patient is a candidate for longer treatment, the clinician should carefully weigh the potential impact on disease-free and overall survival against the potential side effects, as well as assess the patient’s likelihood of adhering to the medication.

With the availability of newer, less-toxic medications that can be tolerated for a greater duration and are easy to administer, aiding in overall treatment compliance, sustained remissions are possible.11-13

Forty years ago, MM patients had very few treatment options, and the 5-year survival rate was 26%.14

Since then, novel therapies, including proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, have replaced conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, leading to major improvements in survival.15,16

With emerging research that supports the value of longer treatment strategies for both patients and the healthcare system, clinicians will have a proven strategy to help their patients attain long-term disease control while maintaining quality of life.2, 17-19

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

2. Goodwin J et al. Cancer Nurs. 2013; 36(4):301-8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182693522

3. Eek D et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016; 10:1609-21. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106629

4. Bauer S et al. Value in Health. 2017; 20: A451. Abstract PCN217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.299

5. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Citrate (MLN9708) Maintenance Therapy in Participants With Multiple Myeloma Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02181413 (Identification No. NCT02181413).

6. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Not Treated With Stem Cell Transplantation. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02312258 (Identification No. NCT02312258).

7. Moreau P et al. Ann Oncol. 2017; 28: iv52-iv61. doi: https://org/10.1093/annonc/mdx096

8. Facon T et al. Blood. 2018131(3):301-310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795047

9. Durie BG et al. Lancet. 2017; 389(10068):519-527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X.

10. Laubach J et al. Leukemia. 2016; 30(5):1005-17. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.356

11. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119: 3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

12. Lehners N et al. Cancer Med. 2018; 7(2): 307–316. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1283

13. Attal M et al. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1872-1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114138

14. National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed March 28, 2018.

15. Kumar SK et al. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2516-20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

16. Fonseca R et al. Leukemia. 2017 Sep;31(9):1915-1921. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.380

17. Palumbo A, Niesvizky R. Leuk Res. 2012; 36 Suppl 1:S19-26. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(12)70005-X

18. Girnius S, Munshi NC. Leuk Suppl. 2013; 2(Suppl 1): S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/leusup.2013.2

19. Mateos M-V, San Miguel JF. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013; 2013:488-95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.488

In Part 2 of this editorial, Katja Weisel, MD, of University Hospital Tubingen in Germany, addresses the barriers to longer treatment in patients with multiple myeloma.

Attitudes regarding longer treatment can present barriers to widespread adoption of this approach in multiple myeloma (MM).

Indeed, some clinicians continue to follow a fixed-duration approach to treatment in MM, only considering further treatment once the patient has relapsed rather than treating the patient until disease progression.

In the MM community, some are reluctant to adopt a strategy of treating longer because of the modest efficacy gains observed with early research or concern over tolerability issues, including the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy or secondary malignancies.1

Others are uncertain about the optimal duration of therapy or the selection of an agent that will balance any potential gain in depth of response with the risk of late-onset or cumulative toxicities.

The potentially high cost of longer treatment for patients, their families, and/or the healthcare system overall also presents a challenge.

It is feasible that treating patients for longer may drive up healthcare utilization and take a toll on patients and caregivers, who may incur out-of-pocket costs because of the need to travel to a hospital or doctor’s office for intravenous therapies, requiring them to miss work.2

It is important to recognize, however, that more convenient all-oral treatment regimens are now available that do not require infusion at a hospital or clinic. Furthermore, results from recent studies suggest the majority of cancer patients prefer oral over intravenous therapies, which could reduce non-pharmacy healthcare costs.3,4

Healthcare providers might be more likely to accept and adopt a longer treatment approach for MM if they had access to data describing the optimal duration, dosage, schedule, toxicity, and quality of life standards.

Ongoing, randomized, phase 3 trials are evaluating the benefits of treating longer with an oral proteasome inhibitor in patients with newly diagnosed MM.5,6

Updated treatment guidelines and consensus statements will provide further guidance for clinicians on the benefits of maintenance therapy in both transplant-eligible and -ineligible patients with newly diagnosed MM.

The recently updated MM guidelines from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommend longer treatment or maintenance therapy in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).7

Based on evidence from studies such as FIRST and SWOG S0777, ESMO also recommends continuous treatment or treatment until progression with lenalidomide-dexamethasone and bortezomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who are ineligible for HSCT.7-9

As there is no one-size-fits-all treatment approach in MM, a personalized treatment plan should be designed for each patient. This plan should take into account a number of factors, including age, disease characteristics, performance status, treatment history, and the patient’s goals of care and personal preferences.10

If the patient is a candidate for longer treatment, the clinician should carefully weigh the potential impact on disease-free and overall survival against the potential side effects, as well as assess the patient’s likelihood of adhering to the medication.

With the availability of newer, less-toxic medications that can be tolerated for a greater duration and are easy to administer, aiding in overall treatment compliance, sustained remissions are possible.11-13

Forty years ago, MM patients had very few treatment options, and the 5-year survival rate was 26%.14

Since then, novel therapies, including proteasome inhibitors and immunomodulatory drugs, have replaced conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy, leading to major improvements in survival.15,16

With emerging research that supports the value of longer treatment strategies for both patients and the healthcare system, clinicians will have a proven strategy to help their patients attain long-term disease control while maintaining quality of life.2, 17-19

Dr. Weisel has received honoraria and/or consultancy fees from Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Juno, Sanofi, and Takeda. She has received research funding from Amgen, Celgene, Sanofi, and Janssen.

The W2O Group provided writing support for this editorial, which was funded by Millennium Pharmaceuticals Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

1. Lipe B et al. Blood Cancer J. 2016; 6(10): e485. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.89

2. Goodwin J et al. Cancer Nurs. 2013; 36(4):301-8. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182693522

3. Eek D et al. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016; 10:1609-21. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S106629

4. Bauer S et al. Value in Health. 2017; 20: A451. Abstract PCN217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.299

5. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Citrate (MLN9708) Maintenance Therapy in Participants With Multiple Myeloma Following Autologous Stem Cell Transplant. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02181413 (Identification No. NCT02181413).

6. A Study of Oral Ixazomib Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Not Treated With Stem Cell Transplantation. (2014). Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02312258 (Identification No. NCT02312258).

7. Moreau P et al. Ann Oncol. 2017; 28: iv52-iv61. doi: https://org/10.1093/annonc/mdx096

8. Facon T et al. Blood. 2018131(3):301-310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-07-795047

9. Durie BG et al. Lancet. 2017; 389(10068):519-527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X.

10. Laubach J et al. Leukemia. 2016; 30(5):1005-17. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.356

11. Ludwig H et al. Blood. 2012; 119: 3003-3015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-11-374249

12. Lehners N et al. Cancer Med. 2018; 7(2): 307–316. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1283

13. Attal M et al. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1872-1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114138

14. National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/. Accessed March 28, 2018.

15. Kumar SK et al. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2516-20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129

16. Fonseca R et al. Leukemia. 2017 Sep;31(9):1915-1921. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.380

17. Palumbo A, Niesvizky R. Leuk Res. 2012; 36 Suppl 1:S19-26. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(12)70005-X

18. Girnius S, Munshi NC. Leuk Suppl. 2013; 2(Suppl 1): S3–S9. doi: 10.1038/leusup.2013.2

19. Mateos M-V, San Miguel JF. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013; 2013:488-95. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.488

Serious side effect of AML treatment going unnoticed, FDA warns

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a safety communication warning that cases of differentiation syndrome are going unnoticed in patients treated with the IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib (Idhifa).

Enasidenib is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and an IDH2 mutation.

The drug is known to be associated with differentiation syndrome, and the prescribing information contains a boxed warning about this life-threatening condition.

However, the FDA has found that patients and healthcare providers are missing the signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome, and some patients are not receiving the necessary treatment in time.

The FDA is also warning that differentiation syndrome has been observed in AML patients taking the IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib (Tibsovo).

However, the agency has not provided many details on cases related to this drug, which is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory AML who have an IDH1 mutation.

Recognizing differentiation syndrome

The FDA says differentiation syndrome may occur anywhere from 10 days to 5 months after starting enasidenib.

The agency is advising healthcare providers to describe the symptoms of differentiation syndrome to patients, both when starting them on enasidenib and at follow-up visits.

Symptoms of differentiation syndrome include:

- Acute respiratory distress represented by dyspnea and/or hypoxia and a need for supplemental oxygen

- Pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusion

- Fever

- Lymphadenopathy

- Bone pain

- Peripheral edema with rapid weight gain

- Pericardial effusion

- Hepatic, renal, and multiorgan dysfunction.

The FDA notes that differentiation syndrome may be mistaken for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonia, or sepsis.

Treatment

If healthcare providers suspect differentiation syndrome, they should promptly administer oral or intravenous corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone at 10 mg every 12 hours, according to the FDA.

Providers should also monitor hemodynamics until improvement and provide supportive care as necessary.

If patients continue to experience renal dysfunction or severe pulmonary symptoms requiring intubation or ventilator support for more than 48 hours after starting corticosteroids, enasidenib should be stopped until signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome are no longer severe.

Corticosteroids should be tapered only after the symptoms resolve completely, as differentiation syndrome may recur if treatment is stopped too soon.

Cases of differentiation syndrome

The FDA notes that, in the phase 1/2 trial that supported the U.S. approval of enasidenib, at least 14% of patients experienced differentiation syndrome.

The manufacturer’s latest safety report includes 5 deaths (from May 1, 2018, to July 31, 2018) associated with differentiation syndrome in patients taking enasidenib.

Differentiation syndrome was listed as the only cause of death in two cases. In the remaining three cases, patients also had hemorrhagic stroke, pneumonia and sepsis, and sepsis alone.

One patient received systemic corticosteroids promptly but may have died of sepsis during hospitalization. In another patient, differentiation syndrome was not diagnosed or treated promptly. Treatment details are not available for the remaining three patients, according to the FDA.

The FDA has also performed a systematic analysis of differentiation syndrome in 293 patients treated with enasidenib (n=214) or ivosidenib (n=179).

With both drugs, the incidence of differentiation syndrome was 19%. The condition was fatal in 6% (n=2) of ivosidenib-treated patients and 5% (n=2) of enasidenib-treated patients.

Additional results from this analysis are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 288).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a safety communication warning that cases of differentiation syndrome are going unnoticed in patients treated with the IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib (Idhifa).

Enasidenib is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and an IDH2 mutation.

The drug is known to be associated with differentiation syndrome, and the prescribing information contains a boxed warning about this life-threatening condition.

However, the FDA has found that patients and healthcare providers are missing the signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome, and some patients are not receiving the necessary treatment in time.

The FDA is also warning that differentiation syndrome has been observed in AML patients taking the IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib (Tibsovo).

However, the agency has not provided many details on cases related to this drug, which is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory AML who have an IDH1 mutation.

Recognizing differentiation syndrome

The FDA says differentiation syndrome may occur anywhere from 10 days to 5 months after starting enasidenib.

The agency is advising healthcare providers to describe the symptoms of differentiation syndrome to patients, both when starting them on enasidenib and at follow-up visits.

Symptoms of differentiation syndrome include:

- Acute respiratory distress represented by dyspnea and/or hypoxia and a need for supplemental oxygen

- Pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusion

- Fever

- Lymphadenopathy

- Bone pain

- Peripheral edema with rapid weight gain

- Pericardial effusion

- Hepatic, renal, and multiorgan dysfunction.

The FDA notes that differentiation syndrome may be mistaken for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonia, or sepsis.

Treatment

If healthcare providers suspect differentiation syndrome, they should promptly administer oral or intravenous corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone at 10 mg every 12 hours, according to the FDA.

Providers should also monitor hemodynamics until improvement and provide supportive care as necessary.

If patients continue to experience renal dysfunction or severe pulmonary symptoms requiring intubation or ventilator support for more than 48 hours after starting corticosteroids, enasidenib should be stopped until signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome are no longer severe.

Corticosteroids should be tapered only after the symptoms resolve completely, as differentiation syndrome may recur if treatment is stopped too soon.

Cases of differentiation syndrome

The FDA notes that, in the phase 1/2 trial that supported the U.S. approval of enasidenib, at least 14% of patients experienced differentiation syndrome.

The manufacturer’s latest safety report includes 5 deaths (from May 1, 2018, to July 31, 2018) associated with differentiation syndrome in patients taking enasidenib.

Differentiation syndrome was listed as the only cause of death in two cases. In the remaining three cases, patients also had hemorrhagic stroke, pneumonia and sepsis, and sepsis alone.

One patient received systemic corticosteroids promptly but may have died of sepsis during hospitalization. In another patient, differentiation syndrome was not diagnosed or treated promptly. Treatment details are not available for the remaining three patients, according to the FDA.

The FDA has also performed a systematic analysis of differentiation syndrome in 293 patients treated with enasidenib (n=214) or ivosidenib (n=179).

With both drugs, the incidence of differentiation syndrome was 19%. The condition was fatal in 6% (n=2) of ivosidenib-treated patients and 5% (n=2) of enasidenib-treated patients.

Additional results from this analysis are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 288).

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has released a safety communication warning that cases of differentiation syndrome are going unnoticed in patients treated with the IDH2 inhibitor enasidenib (Idhifa).

Enasidenib is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and an IDH2 mutation.

The drug is known to be associated with differentiation syndrome, and the prescribing information contains a boxed warning about this life-threatening condition.

However, the FDA has found that patients and healthcare providers are missing the signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome, and some patients are not receiving the necessary treatment in time.

The FDA is also warning that differentiation syndrome has been observed in AML patients taking the IDH1 inhibitor ivosidenib (Tibsovo).

However, the agency has not provided many details on cases related to this drug, which is FDA-approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory AML who have an IDH1 mutation.

Recognizing differentiation syndrome

The FDA says differentiation syndrome may occur anywhere from 10 days to 5 months after starting enasidenib.

The agency is advising healthcare providers to describe the symptoms of differentiation syndrome to patients, both when starting them on enasidenib and at follow-up visits.

Symptoms of differentiation syndrome include:

- Acute respiratory distress represented by dyspnea and/or hypoxia and a need for supplemental oxygen

- Pulmonary infiltrates and pleural effusion

- Fever

- Lymphadenopathy

- Bone pain

- Peripheral edema with rapid weight gain

- Pericardial effusion

- Hepatic, renal, and multiorgan dysfunction.

The FDA notes that differentiation syndrome may be mistaken for cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pneumonia, or sepsis.

Treatment

If healthcare providers suspect differentiation syndrome, they should promptly administer oral or intravenous corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone at 10 mg every 12 hours, according to the FDA.

Providers should also monitor hemodynamics until improvement and provide supportive care as necessary.

If patients continue to experience renal dysfunction or severe pulmonary symptoms requiring intubation or ventilator support for more than 48 hours after starting corticosteroids, enasidenib should be stopped until signs and symptoms of differentiation syndrome are no longer severe.

Corticosteroids should be tapered only after the symptoms resolve completely, as differentiation syndrome may recur if treatment is stopped too soon.

Cases of differentiation syndrome

The FDA notes that, in the phase 1/2 trial that supported the U.S. approval of enasidenib, at least 14% of patients experienced differentiation syndrome.

The manufacturer’s latest safety report includes 5 deaths (from May 1, 2018, to July 31, 2018) associated with differentiation syndrome in patients taking enasidenib.

Differentiation syndrome was listed as the only cause of death in two cases. In the remaining three cases, patients also had hemorrhagic stroke, pneumonia and sepsis, and sepsis alone.

One patient received systemic corticosteroids promptly but may have died of sepsis during hospitalization. In another patient, differentiation syndrome was not diagnosed or treated promptly. Treatment details are not available for the remaining three patients, according to the FDA.

The FDA has also performed a systematic analysis of differentiation syndrome in 293 patients treated with enasidenib (n=214) or ivosidenib (n=179).

With both drugs, the incidence of differentiation syndrome was 19%. The condition was fatal in 6% (n=2) of ivosidenib-treated patients and 5% (n=2) of enasidenib-treated patients.

Additional results from this analysis are scheduled to be presented at the 2018 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 288).

FDA approves gilteritinib for relapsed/refractory AML

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved gilteritinib (Xospata) for use in adults who have relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a FLT3 mutation, as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA also expanded the approved indication for the LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay to include use with gilteritinib.

The LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay, developed by Invivoscribe Technologies, Inc., is used to detect FLT3 mutations in patients with AML.

Gilteritinib, developed by Astellas Pharma, has demonstrated inhibitory activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain.

The FDA’s approval of gilteritinib was based on an interim analysis of the ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939).

The trial enrolled adults with relapsed or refractory AML who had a FLT3 ITD, D835, or I836 mutation, according to the LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay.

Patients received gilteritinib at 120 mg daily until they developed unacceptable toxicity or did not show a clinical benefit.

Efficacy results are available for 138 patients, with a median follow-up of 4.6 months (range, 2.8 to 15.8).

The complete response (CR) rate was 11.6% (16/138), the rate of CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) was 9.4% (13/138), and the rate of CR/CRh was 21% (29/138).

The median duration of CR/CRh was 4.6 months.

There were 106 patients who were transfusion-dependent at baseline, and 33 of these patients (31.1%) became transfusion-independent during the post-baseline period.

Seventeen of the 32 patients (53.1%) who were transfusion-independent at baseline remained transfusion-independent.

Safety results are available for 292 patients. The median duration of exposure to gilteritinib in this group was 3 months (range, 0.1 to 42.8).

The most common adverse events were myalgia/arthralgia (42%), transaminase increase (41%), fatigue/malaise (40%), fever (35%), noninfectious diarrhea (34%), dyspnea (34%), edema (34%), rash (30%), pneumonia (30%), nausea (27%), constipation (27%), stomatitis (26%), cough (25%), headache (21%), hypotension (21%), dizziness (20%), and vomiting (20%).

Eight percent of patients (n=22) discontinued gilteritinib due to adverse events. The most common were pneumonia (2%), sepsis (2%), and dyspnea (1%).

For more details on the ADMIRAL trial and gilteritinib, see the full prescribing information.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved gilteritinib (Xospata) for use in adults who have relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a FLT3 mutation, as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA also expanded the approved indication for the LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay to include use with gilteritinib.

The LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay, developed by Invivoscribe Technologies, Inc., is used to detect FLT3 mutations in patients with AML.

Gilteritinib, developed by Astellas Pharma, has demonstrated inhibitory activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain.

The FDA’s approval of gilteritinib was based on an interim analysis of the ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939).

The trial enrolled adults with relapsed or refractory AML who had a FLT3 ITD, D835, or I836 mutation, according to the LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay.

Patients received gilteritinib at 120 mg daily until they developed unacceptable toxicity or did not show a clinical benefit.

Efficacy results are available for 138 patients, with a median follow-up of 4.6 months (range, 2.8 to 15.8).

The complete response (CR) rate was 11.6% (16/138), the rate of CR with partial hematologic recovery (CRh) was 9.4% (13/138), and the rate of CR/CRh was 21% (29/138).

The median duration of CR/CRh was 4.6 months.

There were 106 patients who were transfusion-dependent at baseline, and 33 of these patients (31.1%) became transfusion-independent during the post-baseline period.

Seventeen of the 32 patients (53.1%) who were transfusion-independent at baseline remained transfusion-independent.

Safety results are available for 292 patients. The median duration of exposure to gilteritinib in this group was 3 months (range, 0.1 to 42.8).

The most common adverse events were myalgia/arthralgia (42%), transaminase increase (41%), fatigue/malaise (40%), fever (35%), noninfectious diarrhea (34%), dyspnea (34%), edema (34%), rash (30%), pneumonia (30%), nausea (27%), constipation (27%), stomatitis (26%), cough (25%), headache (21%), hypotension (21%), dizziness (20%), and vomiting (20%).

Eight percent of patients (n=22) discontinued gilteritinib due to adverse events. The most common were pneumonia (2%), sepsis (2%), and dyspnea (1%).

For more details on the ADMIRAL trial and gilteritinib, see the full prescribing information.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved gilteritinib (Xospata) for use in adults who have relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a FLT3 mutation, as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA also expanded the approved indication for the LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay to include use with gilteritinib.

The LeukoStrat CDx FLT3 Mutation Assay, developed by Invivoscribe Technologies, Inc., is used to detect FLT3 mutations in patients with AML.

Gilteritinib, developed by Astellas Pharma, has demonstrated inhibitory activity against FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain.

The FDA’s approval of gilteritinib was based on an interim analysis of the ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939).