User login

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

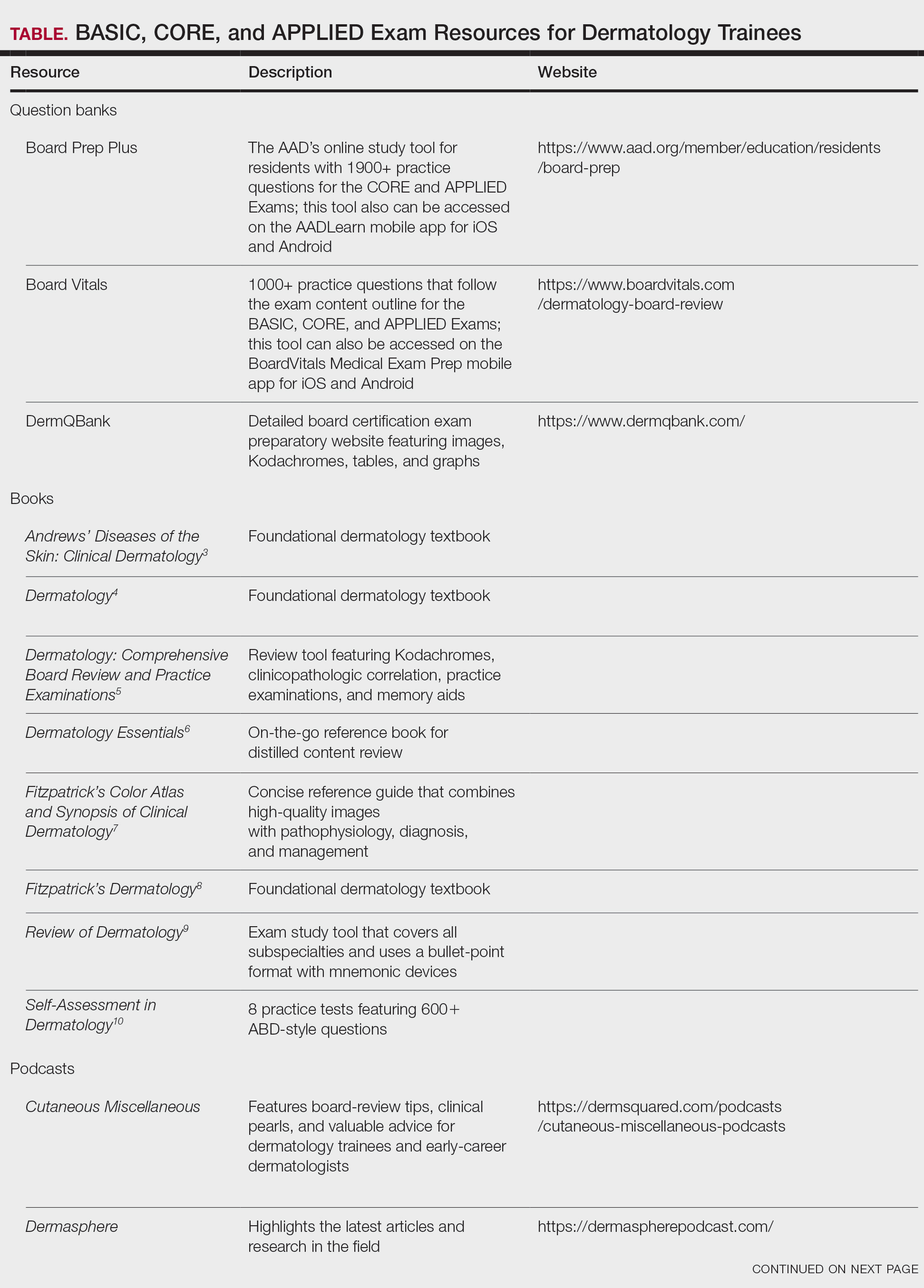

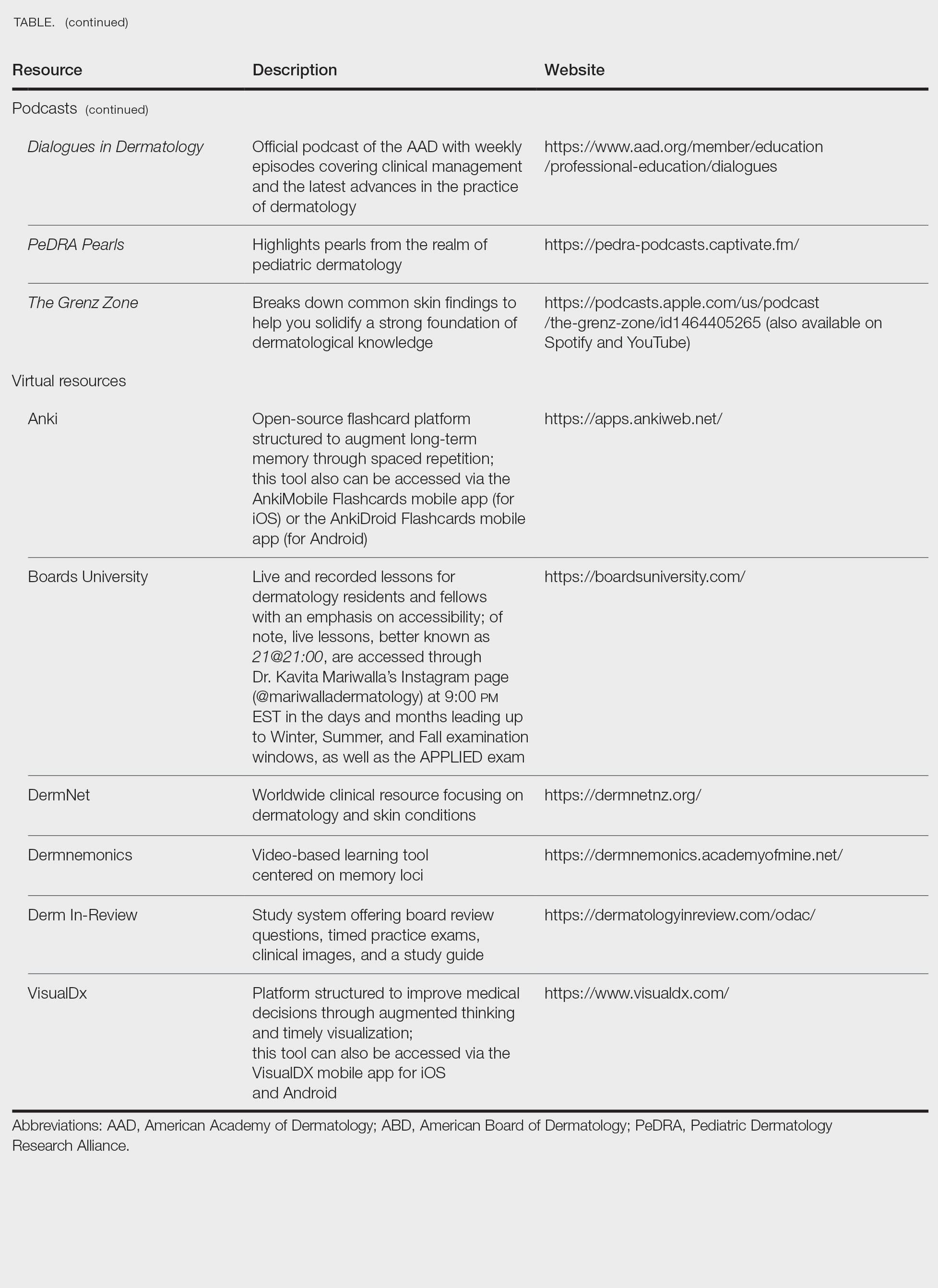

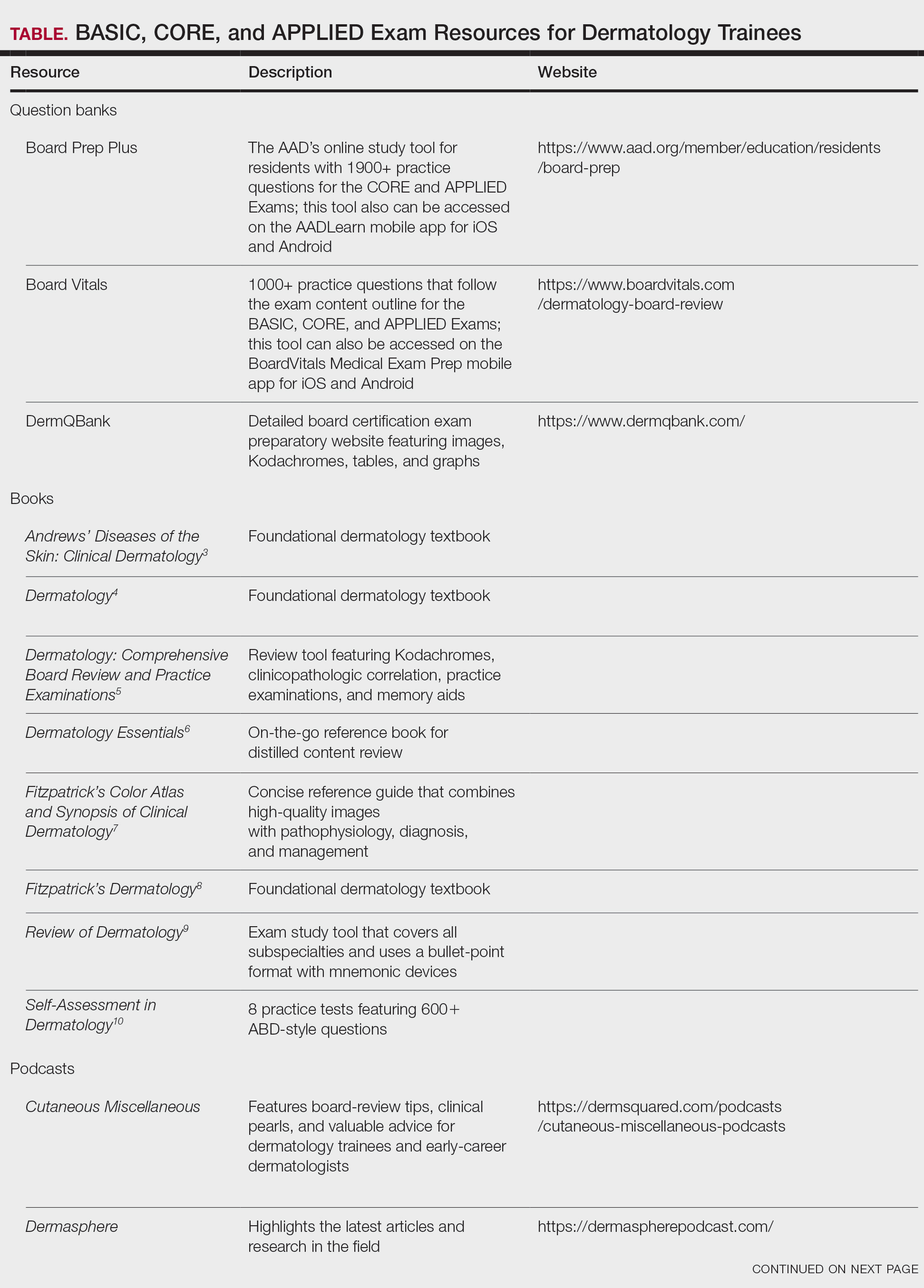

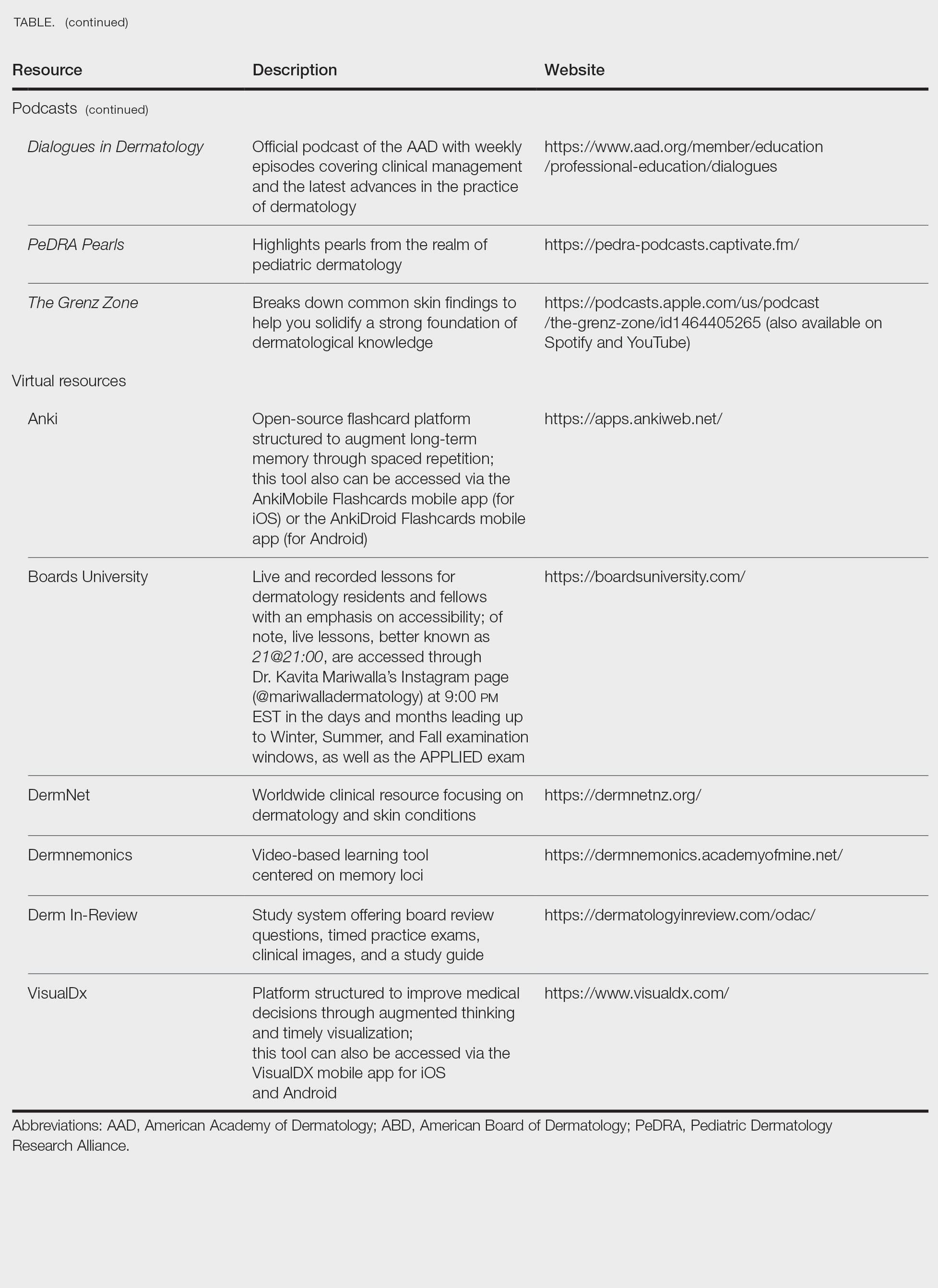

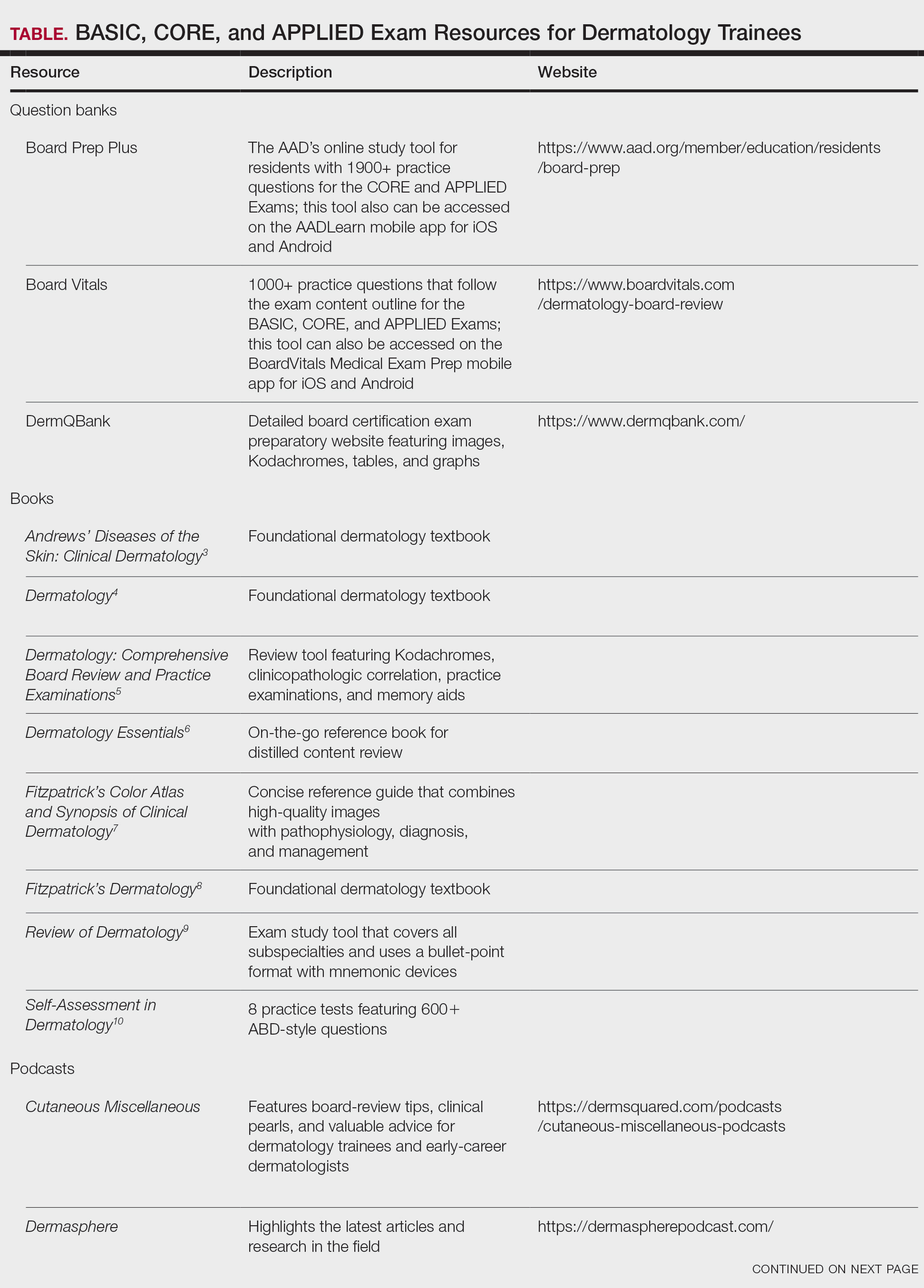

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations, culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the USMLE Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside of clinical responsibilities (Table). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for additional ones to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you can also consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Practice Points

- To become a board-certified dermatologist, one must complete the American Board of Dermatology Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, followed by 4 CORE Exam modules and a final APPLIED Exam following residency completion.

- When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore fully. With so many options available, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style.

- A comprehensive study strategy begins during your first year of residency and appropriately intensifies in the months leading up to the exams. Make sure to cultivate test day strategies to help you stay calm, focused, and in the zone.

Perceptions of Community Service in Dermatology Residency Training Programs: A Survey-Based Study of Program Directors, Residents, and Recent Dermatology Residency Graduates

Community service (CS) or service learning in dermatology (eg, free skin cancer screenings, providing care through free clinics, free teledermatology consultations) is instrumental in mitigating disparities and improving access to equitable dermatologic care. With the rate of underinsured and uninsured patients on the rise, free and federally qualified clinics frequently are the sole means by which patients access specialty care such as dermatology.1 Contributing to the economic gap in access, the geographic disparity of dermatologists in the United States continues to climb, and many marginalized communities remain without dermatologists.2 Nearly 30% of the total US population resides in geographic areas that are underserved by dermatologists, while there appears to be an oversupply of dermatologists in urban areas.3 Dermatologists practicing in rural areas make up only 10% of the dermatology workforce,4 whereas 40% of all dermatologists practice in the most densely populated US cities.5 Consequently, patients in these underserved communities face longer wait times6 and are less likely to utilize dermatology services than patients in dermatologist-dense geographic areas.7

Service opportunities have become increasingly integrated into graduate medical education.8 These service activities help bridge the health care access gap while fulfilling Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements. Our study assessed the importance of CS to dermatology residency program directors (PDs), dermatology residents, and recent dermatology residency graduates. Herein, we describe the perceptions of CS within dermatology residency training among PDs and residents.

Methods

In this study, CS is defined as participation in activities to increase dermatologic access, education, and resources to underserved communities. Using the approved Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve and direct email communication, we surveyed 142 PDs of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency training programs. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 17-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

We also surveyed current dermatology residents and recent graduates of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs via PDs nationwide. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 19-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis for both Qualtrics surveys. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board deemed this study exempt.

Results

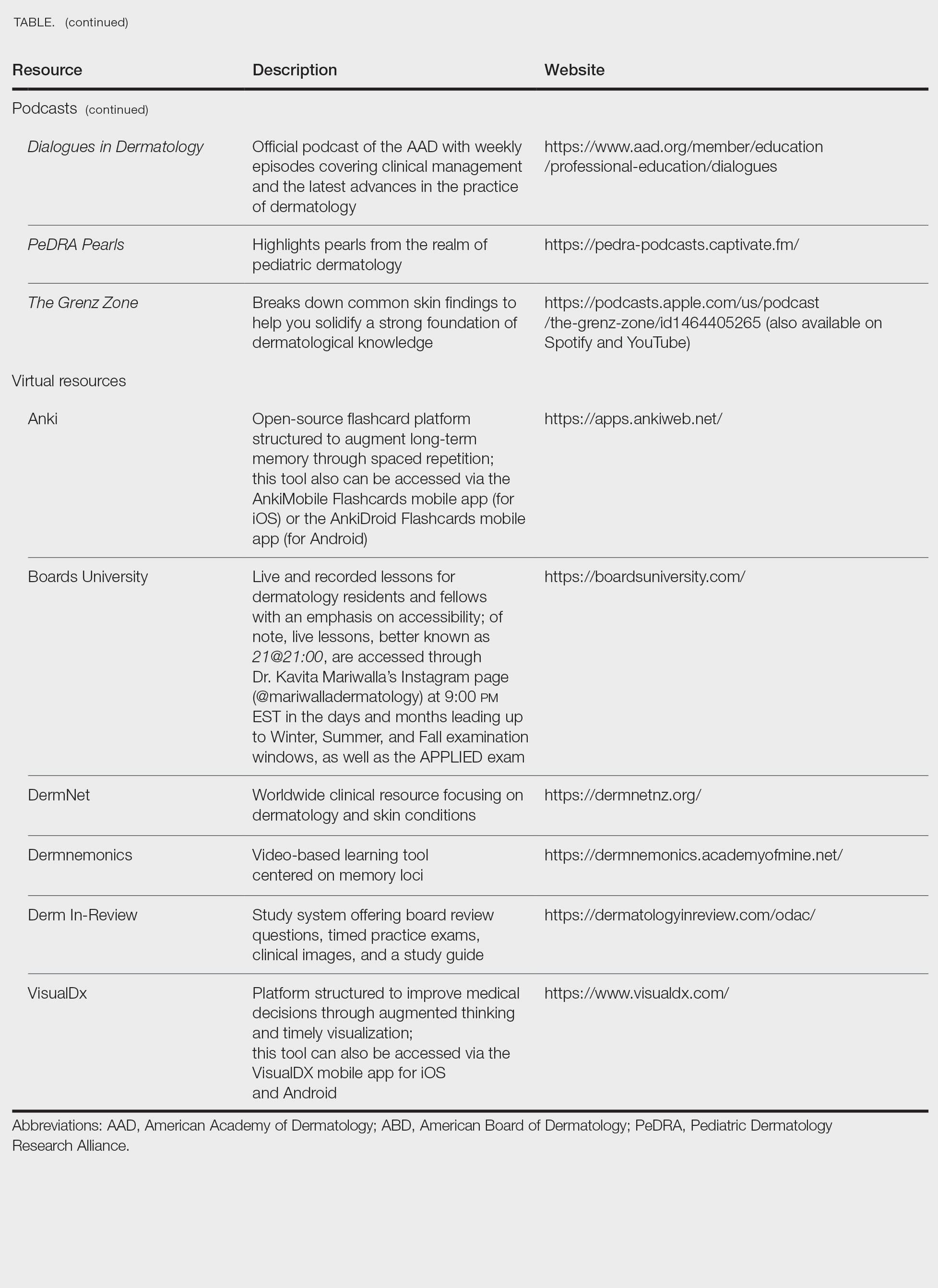

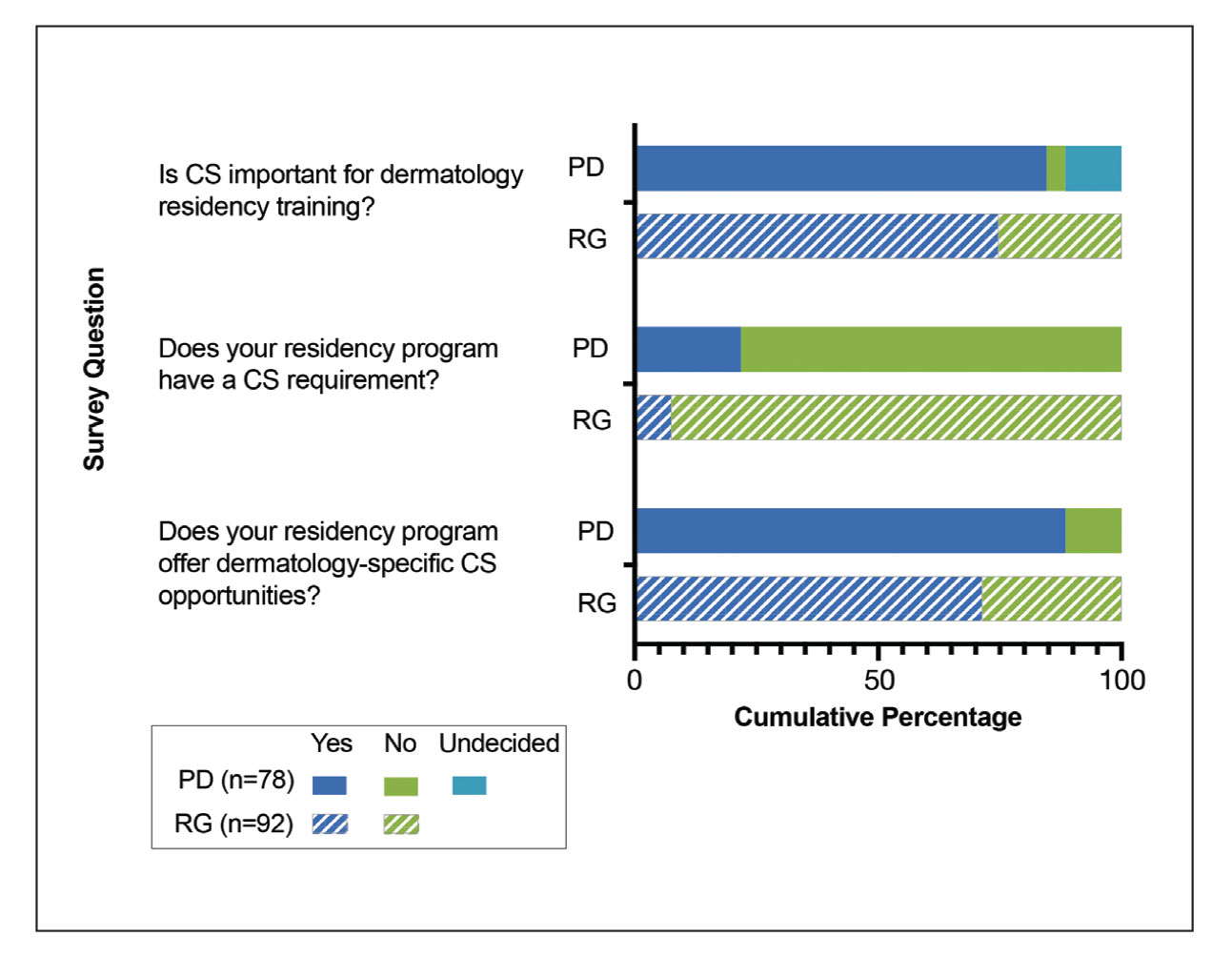

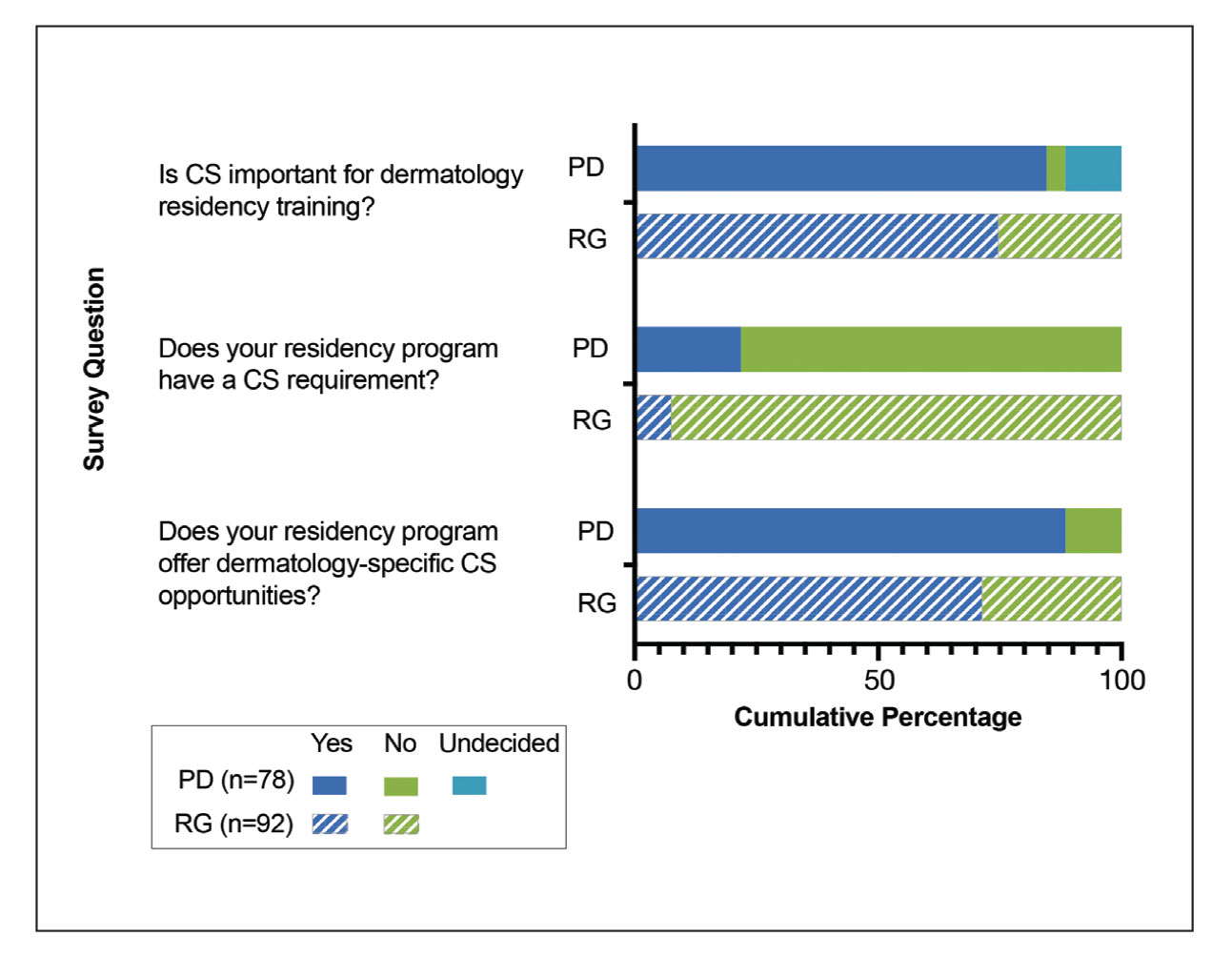

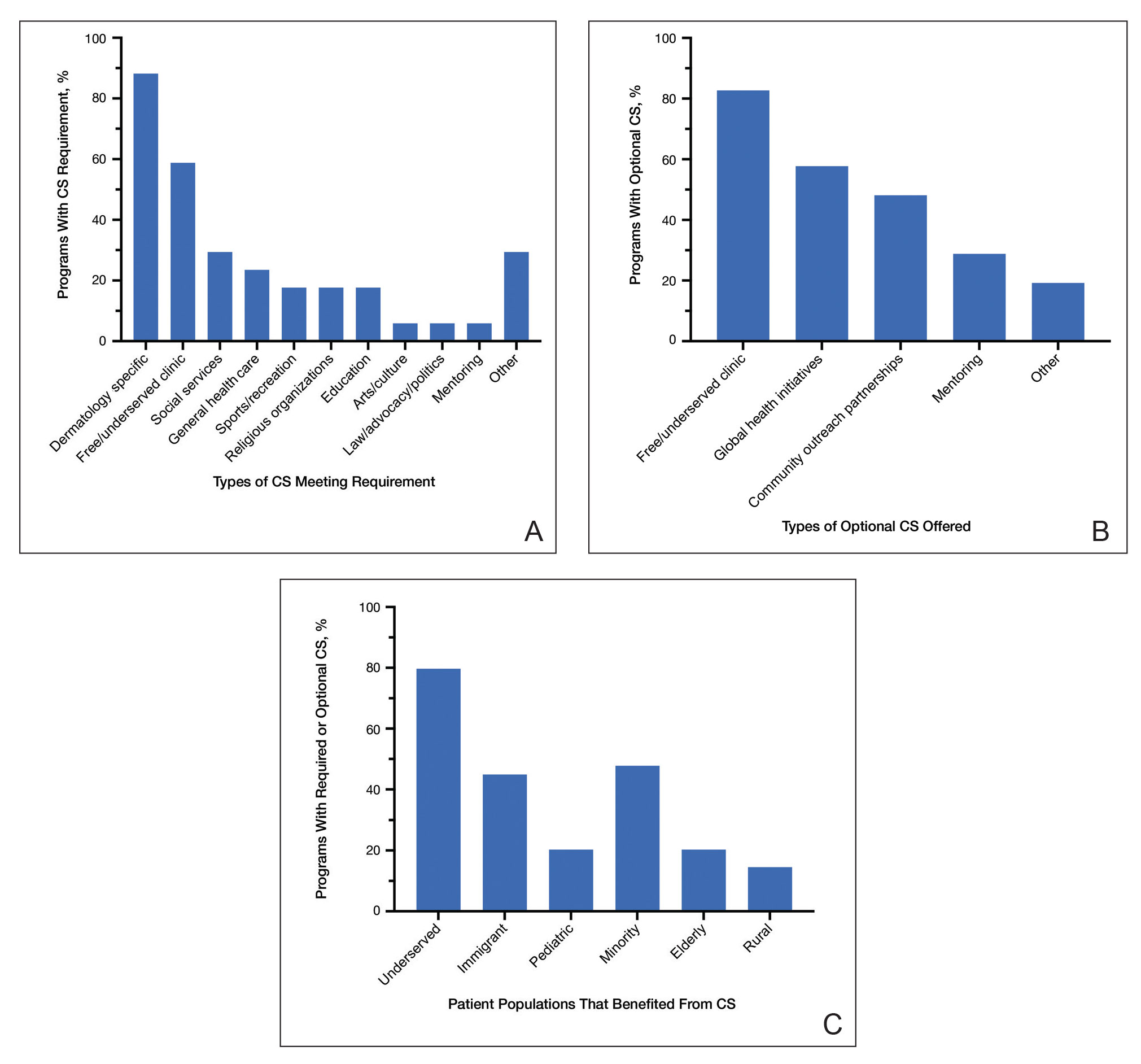

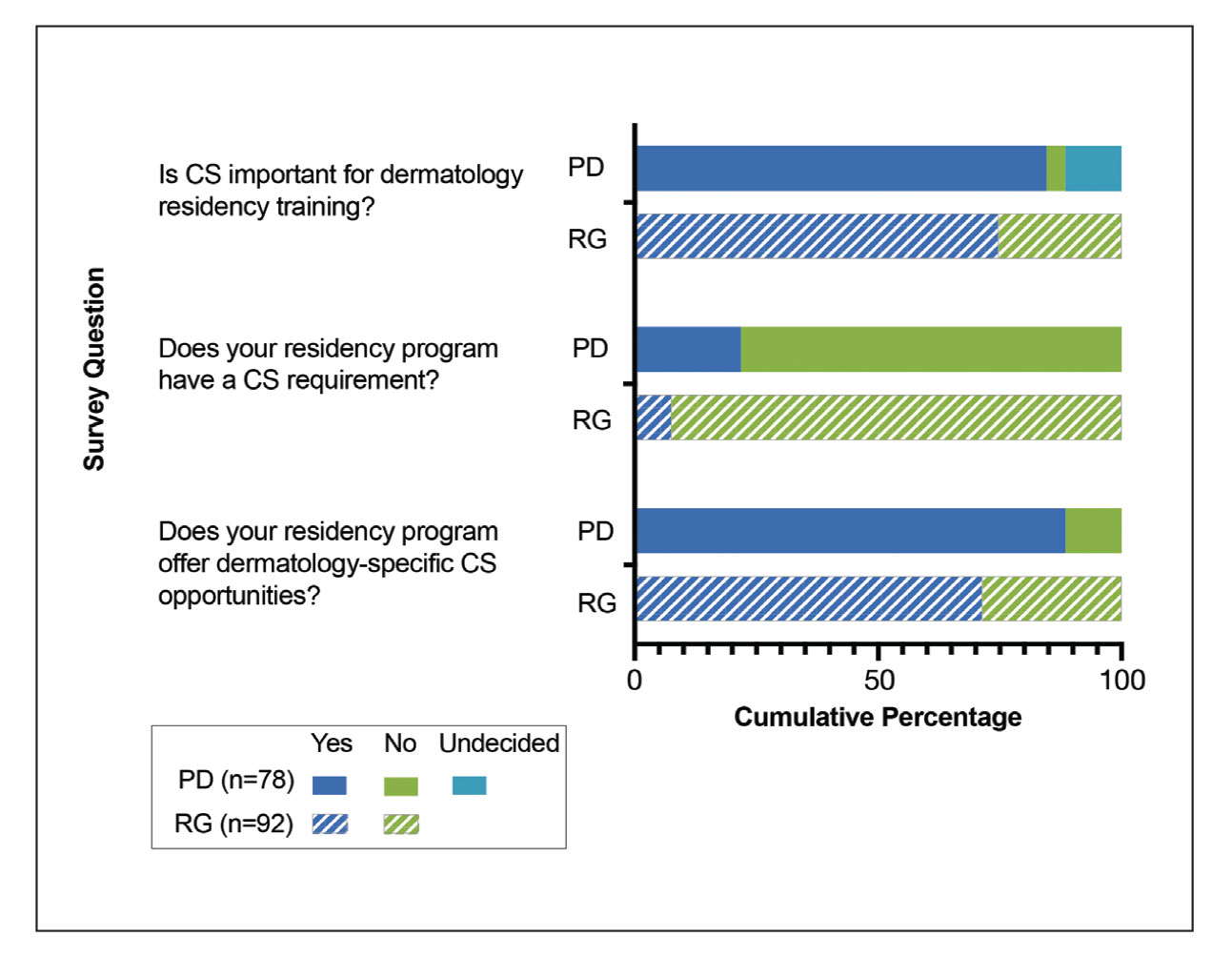

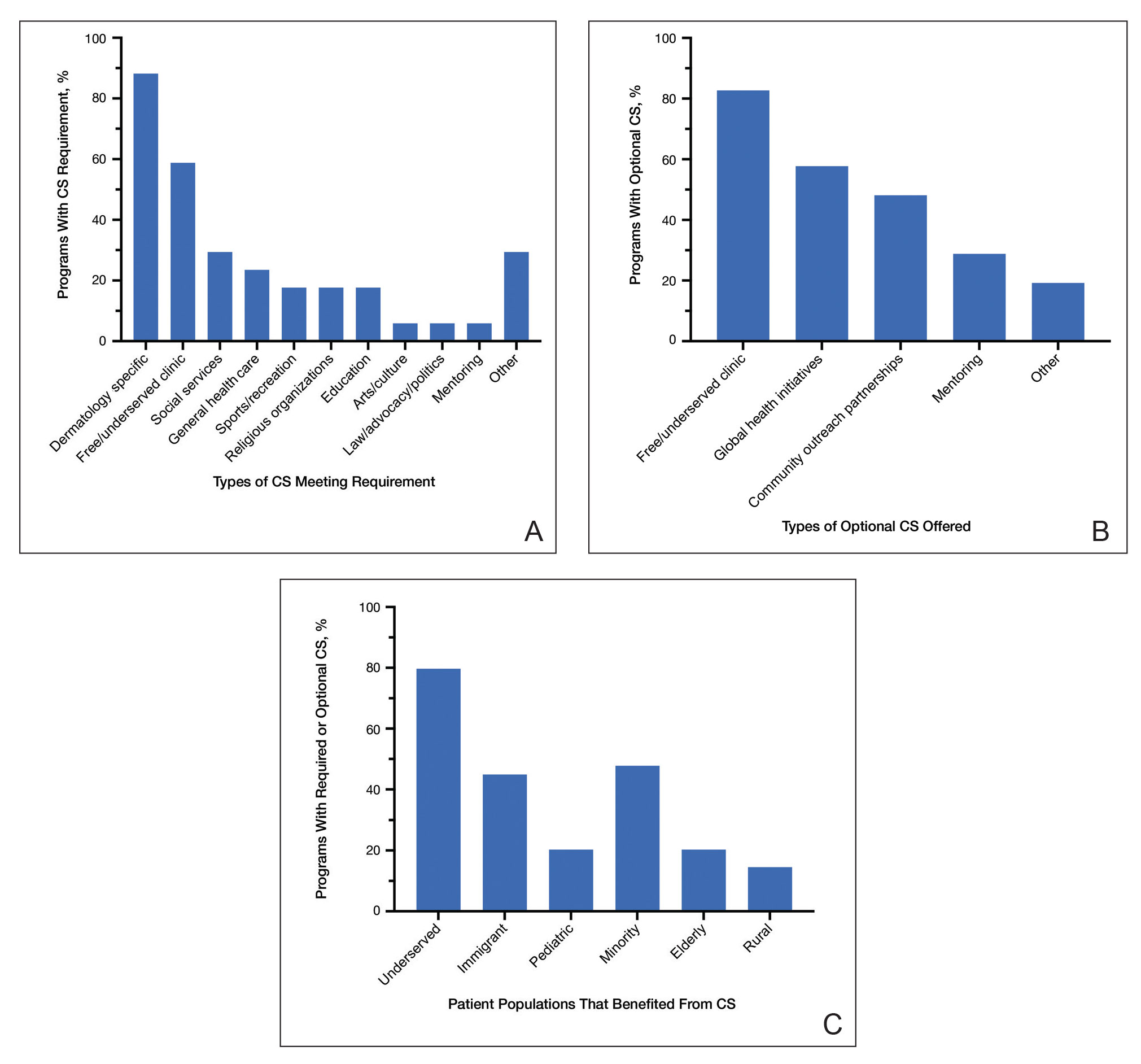

Feedback From PDs—Of the 142 PDs, we received 78 responses (54.9%). For selection of dermatology residents, CS was moderately to extremely important to 64 (82.1%) PDs, and 63 (80.8%) PDs stated CS was moderately to extremely important to their dermatology residency program at large. For dermatology residency training, 66 (84.6%) PDs believed CS is important, whereas 3 (3.8%) believed it is not important, and 9 (11.5%) remained undecided (Figure 1). Notably, 17 (21.8%) programs required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum, with most of these programs requiring 10 hours or less during the 3 years of residency training. Of the programs with required CS, 15 (88.2%) had dermatology-specific CS requirements, with 10 (58.8%) programs involved in CS at free and/or underserved clinics and some programs participating in other CS activities, such as advocacy, mentorship, educational outreach, or sports (Figure 2A).

Community service opportunities were offered to dermatology residents by 69 (88.5%) programs, including the 17 programs that required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum. Among these programs with optional CS, 43 (82.7%) PDs reported CS opportunities at free and/or underserved clinics, and 30 (57.7%) reported CS opportunities through global health initiatives (Figure 2B). Other CS opportunities offered included partnerships with community outreach organizations and mentoring underprivileged students. Patient populations that benefit from CS offered by these dermatology residency programs included 55 (79.7%) underserved, 33 (47.8%) minority, 31 (44.9%) immigrant, 14 (20.3%) pediatric, 14 (20.3%) elderly, and 10 (14.5%) rural populations (Figure 2C). At dermatology residency programs with optional CS opportunities, 22 (42.3%) PDs endorsed at least 50% of their residents participating in these activities.

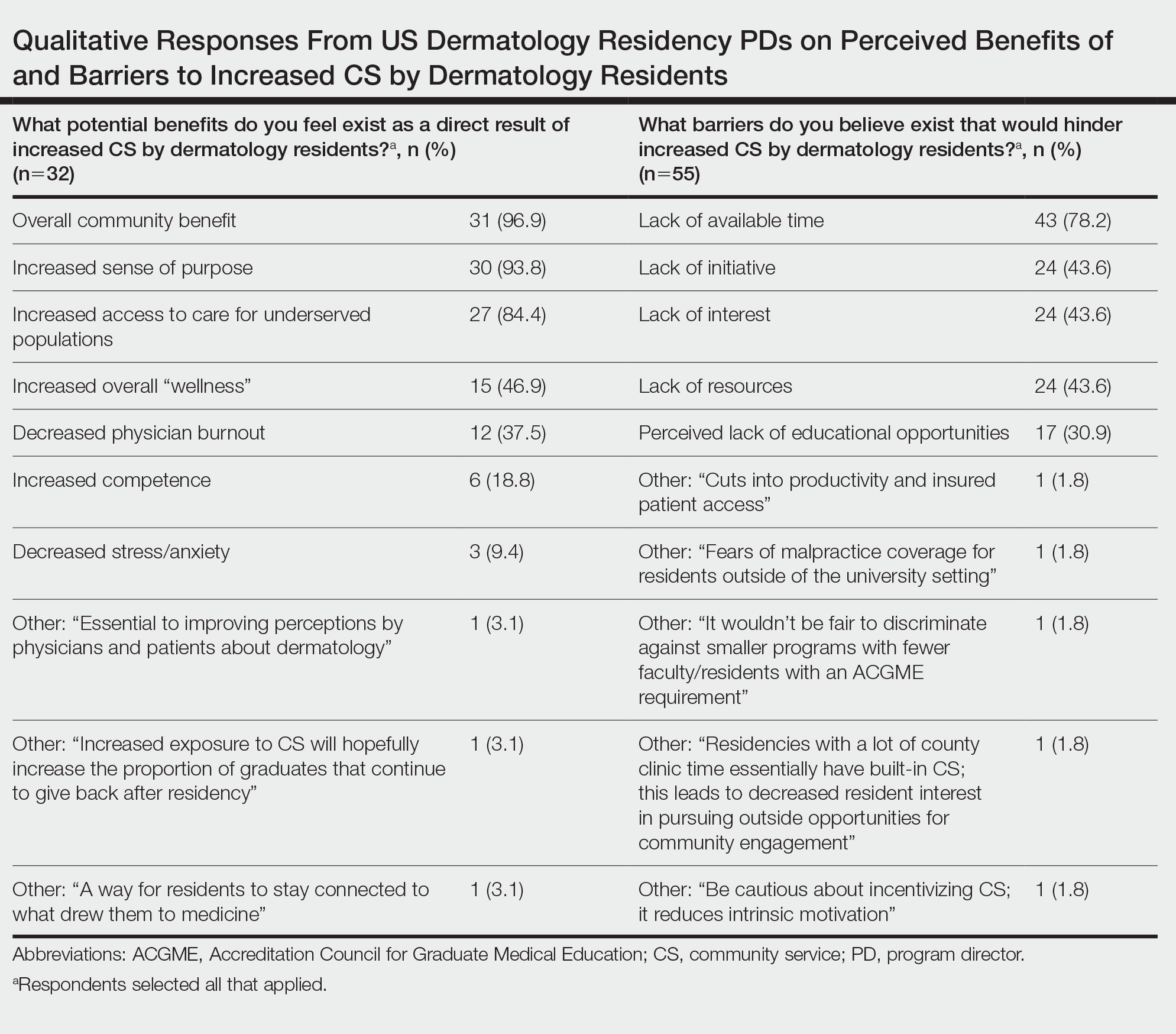

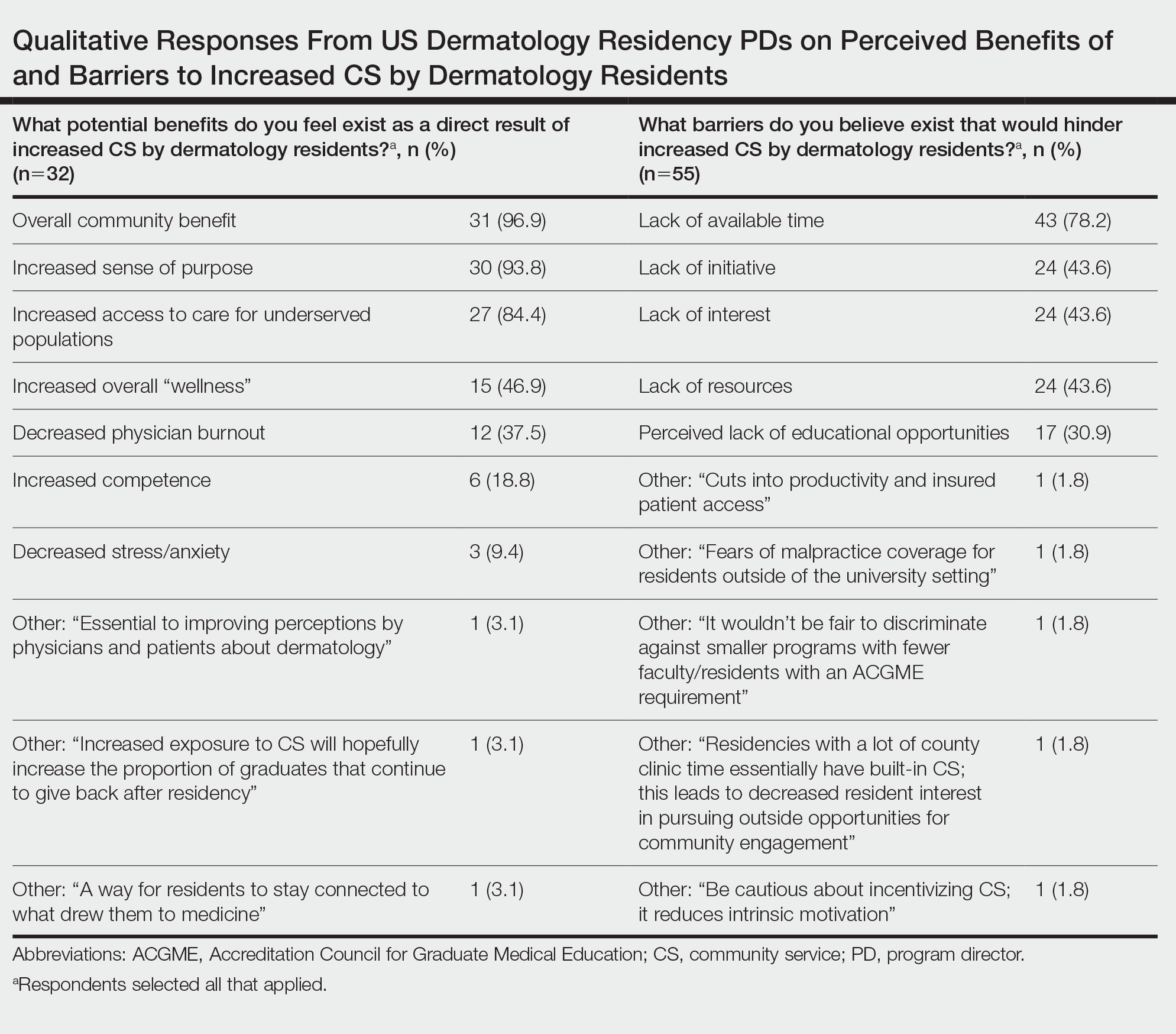

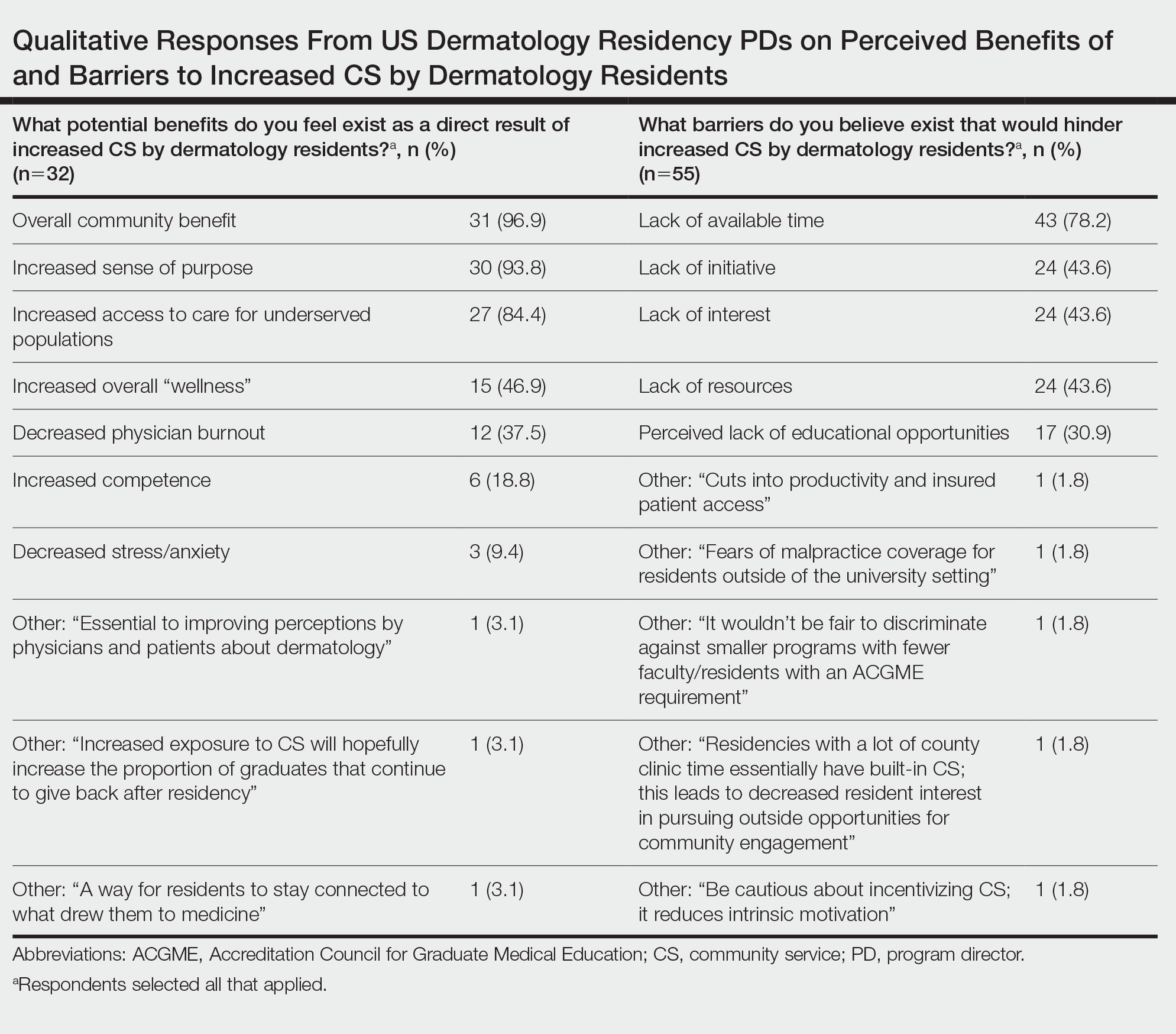

Qualitative responses revealed that some PDs view CS as “a way for residents to stay connected to what drew them to medicine” and “essential to improving perceptions by physicians and patients about dermatology.” Program directors perceived lack of available time, initiative, and resources as well as minimal resident interest, malpractice coverage, and lack of educational opportunities as potential barriers to CS involvement by residents (Table). Forty-six (59.0%) PDs believed that CS should not be an ACGME requirement for dermatology training, 23 (29.5%) believed it should be required, and 9 (11.5%) were undecided.

Feedback From Residents—We received responses from 92 current dermatology residents and recent dermatology residency graduates; 86 (93.5%) respondents were trainees or recent graduates from academic dermatology residency training programs, and 6 (6.5%) were from community-based training programs. Community service was perceived to be an important part of dermatology training by 68 (73.9%) respondents, and dermatology-specific CS opportunities were available to 65 (70.7%) respondents (Figure 1). Although CS was required of only 7 (7.6%) respondents, 36 (39.1%) respondents volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during residency training. Among respondents who were not provided CS opportunities through their residency program, 23 (85.2%) stated they would have participated if given the opportunity.

Dermatology residents listed increased access to care for marginalized populations, increased sense of purpose, increased competence, and decreased burnout as perceived benefits of participation in CS. Of the dermatology residents who volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during training, 27 (75.0%) regarded the experience as a “high-yield learning opportunity.” Additionally, 29 (80.6%) residents stated their participation in a free dermatology clinic increased their awareness of health disparities and societal factors affecting dermatologic care in underserved patient populations. These respondents affirmed that their participation motivated them to become more involved in outreach targeting underserved populations throughout the duration of their careers.

Comment

The results of this nationwide survey have several important implications for dermatology residency programs, with a focus on programs in well-resourced and high socioeconomic status areas. Although most PDs believe that CS is important for dermatology resident training, few programs have CS requirements, and the majority are opposed to ACGME-mandated CS. Dermatology residents and recent graduates overwhelmingly conveyed that participation in a free dermatology clinic during residency training increased their knowledge base surrounding socioeconomic determinants of health and practicing in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, most trainees expressed that CS participation as a resident motivated them to continue to partake in CS for the underserved as an attending physician. The discordance between perceived value of CS by residents and the lack of CS requirements and opportunities by residency programs represents a realistic opportunity for residency training programs to integrate CS into the curriculum.

Residency programs that integrate service for the underserved into their program goals are 3 times more successful in graduating dermatology residents who practice in underserved communities.9 Patients in marginalized communities and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face many barriers to accessing dermatologic care including longer wait times and higher practice rejection rates than patients with private insurance.6 Through increased CS opportunities, dermatology residency programs can strengthen the local health care infrastructure and bridge the gap in access to dermatologic care.

By establishing a formal CS rotation in dermatology residency programs, residents will experience invaluable first-hand educational opportunities, provide comprehensive care for patients in resource-limited settings, and hopefully continue to serve in marginalized communities. Incorporating service for the underserved into the dermatology residency curriculum not only enhances the cultural competency of trainees but also mandates that skin health equity be made a priority. By exposing dermatology residents to the diverse patient populations often served by free clinics, residents will increase their knowledge of skin disease presentation in patients with darker skin tones, which has historically been deficient in medical education.10,11

The limitations of this survey study included recall bias, the response rate of PDs (54.9%), and the inability to determine response rate of residents, as we were unable to establish the total number of residents who received our survey. Based on geographic location, some dermatology residency programs may treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients, which already improves access to dermatology. For this reason, follow-up studies correlating PD and resident responses with region, program size, and university/community affiliation will increase our understanding of CS participation and perceptions.

Conclusion

Dermatology residency program participation in CS helps reduce barriers to access for patients in marginalized communities. Incorporating CS into the dermatology residency program curriculum creates a rewarding training environment that increases skin health equity, fosters an interest in health disparities, and enhances the cultural competency of its trainees.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

- Vaidya T, Zubritsky L, Alikhan A, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic barriers to dermatology care in urban and rural US populations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:406-408.

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307.

- Resneck J, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Resneck J, Pletcher MJ, Lozano N. Medicare, Medicaid, and access to dermatologists: the effect of patient insurance on appointment access and wait times. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:85-92.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Vance MC, Kennedy KG. Developing an advocacy curriculum: lessons learned from a national survey of psychiatric residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:283-288.

- Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

Community service (CS) or service learning in dermatology (eg, free skin cancer screenings, providing care through free clinics, free teledermatology consultations) is instrumental in mitigating disparities and improving access to equitable dermatologic care. With the rate of underinsured and uninsured patients on the rise, free and federally qualified clinics frequently are the sole means by which patients access specialty care such as dermatology.1 Contributing to the economic gap in access, the geographic disparity of dermatologists in the United States continues to climb, and many marginalized communities remain without dermatologists.2 Nearly 30% of the total US population resides in geographic areas that are underserved by dermatologists, while there appears to be an oversupply of dermatologists in urban areas.3 Dermatologists practicing in rural areas make up only 10% of the dermatology workforce,4 whereas 40% of all dermatologists practice in the most densely populated US cities.5 Consequently, patients in these underserved communities face longer wait times6 and are less likely to utilize dermatology services than patients in dermatologist-dense geographic areas.7

Service opportunities have become increasingly integrated into graduate medical education.8 These service activities help bridge the health care access gap while fulfilling Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements. Our study assessed the importance of CS to dermatology residency program directors (PDs), dermatology residents, and recent dermatology residency graduates. Herein, we describe the perceptions of CS within dermatology residency training among PDs and residents.

Methods

In this study, CS is defined as participation in activities to increase dermatologic access, education, and resources to underserved communities. Using the approved Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve and direct email communication, we surveyed 142 PDs of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency training programs. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 17-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

We also surveyed current dermatology residents and recent graduates of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs via PDs nationwide. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 19-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis for both Qualtrics surveys. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board deemed this study exempt.

Results

Feedback From PDs—Of the 142 PDs, we received 78 responses (54.9%). For selection of dermatology residents, CS was moderately to extremely important to 64 (82.1%) PDs, and 63 (80.8%) PDs stated CS was moderately to extremely important to their dermatology residency program at large. For dermatology residency training, 66 (84.6%) PDs believed CS is important, whereas 3 (3.8%) believed it is not important, and 9 (11.5%) remained undecided (Figure 1). Notably, 17 (21.8%) programs required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum, with most of these programs requiring 10 hours or less during the 3 years of residency training. Of the programs with required CS, 15 (88.2%) had dermatology-specific CS requirements, with 10 (58.8%) programs involved in CS at free and/or underserved clinics and some programs participating in other CS activities, such as advocacy, mentorship, educational outreach, or sports (Figure 2A).

Community service opportunities were offered to dermatology residents by 69 (88.5%) programs, including the 17 programs that required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum. Among these programs with optional CS, 43 (82.7%) PDs reported CS opportunities at free and/or underserved clinics, and 30 (57.7%) reported CS opportunities through global health initiatives (Figure 2B). Other CS opportunities offered included partnerships with community outreach organizations and mentoring underprivileged students. Patient populations that benefit from CS offered by these dermatology residency programs included 55 (79.7%) underserved, 33 (47.8%) minority, 31 (44.9%) immigrant, 14 (20.3%) pediatric, 14 (20.3%) elderly, and 10 (14.5%) rural populations (Figure 2C). At dermatology residency programs with optional CS opportunities, 22 (42.3%) PDs endorsed at least 50% of their residents participating in these activities.

Qualitative responses revealed that some PDs view CS as “a way for residents to stay connected to what drew them to medicine” and “essential to improving perceptions by physicians and patients about dermatology.” Program directors perceived lack of available time, initiative, and resources as well as minimal resident interest, malpractice coverage, and lack of educational opportunities as potential barriers to CS involvement by residents (Table). Forty-six (59.0%) PDs believed that CS should not be an ACGME requirement for dermatology training, 23 (29.5%) believed it should be required, and 9 (11.5%) were undecided.

Feedback From Residents—We received responses from 92 current dermatology residents and recent dermatology residency graduates; 86 (93.5%) respondents were trainees or recent graduates from academic dermatology residency training programs, and 6 (6.5%) were from community-based training programs. Community service was perceived to be an important part of dermatology training by 68 (73.9%) respondents, and dermatology-specific CS opportunities were available to 65 (70.7%) respondents (Figure 1). Although CS was required of only 7 (7.6%) respondents, 36 (39.1%) respondents volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during residency training. Among respondents who were not provided CS opportunities through their residency program, 23 (85.2%) stated they would have participated if given the opportunity.

Dermatology residents listed increased access to care for marginalized populations, increased sense of purpose, increased competence, and decreased burnout as perceived benefits of participation in CS. Of the dermatology residents who volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during training, 27 (75.0%) regarded the experience as a “high-yield learning opportunity.” Additionally, 29 (80.6%) residents stated their participation in a free dermatology clinic increased their awareness of health disparities and societal factors affecting dermatologic care in underserved patient populations. These respondents affirmed that their participation motivated them to become more involved in outreach targeting underserved populations throughout the duration of their careers.

Comment

The results of this nationwide survey have several important implications for dermatology residency programs, with a focus on programs in well-resourced and high socioeconomic status areas. Although most PDs believe that CS is important for dermatology resident training, few programs have CS requirements, and the majority are opposed to ACGME-mandated CS. Dermatology residents and recent graduates overwhelmingly conveyed that participation in a free dermatology clinic during residency training increased their knowledge base surrounding socioeconomic determinants of health and practicing in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, most trainees expressed that CS participation as a resident motivated them to continue to partake in CS for the underserved as an attending physician. The discordance between perceived value of CS by residents and the lack of CS requirements and opportunities by residency programs represents a realistic opportunity for residency training programs to integrate CS into the curriculum.

Residency programs that integrate service for the underserved into their program goals are 3 times more successful in graduating dermatology residents who practice in underserved communities.9 Patients in marginalized communities and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face many barriers to accessing dermatologic care including longer wait times and higher practice rejection rates than patients with private insurance.6 Through increased CS opportunities, dermatology residency programs can strengthen the local health care infrastructure and bridge the gap in access to dermatologic care.

By establishing a formal CS rotation in dermatology residency programs, residents will experience invaluable first-hand educational opportunities, provide comprehensive care for patients in resource-limited settings, and hopefully continue to serve in marginalized communities. Incorporating service for the underserved into the dermatology residency curriculum not only enhances the cultural competency of trainees but also mandates that skin health equity be made a priority. By exposing dermatology residents to the diverse patient populations often served by free clinics, residents will increase their knowledge of skin disease presentation in patients with darker skin tones, which has historically been deficient in medical education.10,11

The limitations of this survey study included recall bias, the response rate of PDs (54.9%), and the inability to determine response rate of residents, as we were unable to establish the total number of residents who received our survey. Based on geographic location, some dermatology residency programs may treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients, which already improves access to dermatology. For this reason, follow-up studies correlating PD and resident responses with region, program size, and university/community affiliation will increase our understanding of CS participation and perceptions.

Conclusion

Dermatology residency program participation in CS helps reduce barriers to access for patients in marginalized communities. Incorporating CS into the dermatology residency program curriculum creates a rewarding training environment that increases skin health equity, fosters an interest in health disparities, and enhances the cultural competency of its trainees.

Community service (CS) or service learning in dermatology (eg, free skin cancer screenings, providing care through free clinics, free teledermatology consultations) is instrumental in mitigating disparities and improving access to equitable dermatologic care. With the rate of underinsured and uninsured patients on the rise, free and federally qualified clinics frequently are the sole means by which patients access specialty care such as dermatology.1 Contributing to the economic gap in access, the geographic disparity of dermatologists in the United States continues to climb, and many marginalized communities remain without dermatologists.2 Nearly 30% of the total US population resides in geographic areas that are underserved by dermatologists, while there appears to be an oversupply of dermatologists in urban areas.3 Dermatologists practicing in rural areas make up only 10% of the dermatology workforce,4 whereas 40% of all dermatologists practice in the most densely populated US cities.5 Consequently, patients in these underserved communities face longer wait times6 and are less likely to utilize dermatology services than patients in dermatologist-dense geographic areas.7

Service opportunities have become increasingly integrated into graduate medical education.8 These service activities help bridge the health care access gap while fulfilling Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements. Our study assessed the importance of CS to dermatology residency program directors (PDs), dermatology residents, and recent dermatology residency graduates. Herein, we describe the perceptions of CS within dermatology residency training among PDs and residents.

Methods

In this study, CS is defined as participation in activities to increase dermatologic access, education, and resources to underserved communities. Using the approved Association of Professors of Dermatology listserve and direct email communication, we surveyed 142 PDs of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency training programs. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 17-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

We also surveyed current dermatology residents and recent graduates of ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs via PDs nationwide. The deidentified respondents voluntarily completed a 19-question Qualtrics survey with a 5-point Likert scale (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all), yes/no/undecided, and qualitative responses.

Descriptive statistics were used for data analysis for both Qualtrics surveys. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board deemed this study exempt.

Results

Feedback From PDs—Of the 142 PDs, we received 78 responses (54.9%). For selection of dermatology residents, CS was moderately to extremely important to 64 (82.1%) PDs, and 63 (80.8%) PDs stated CS was moderately to extremely important to their dermatology residency program at large. For dermatology residency training, 66 (84.6%) PDs believed CS is important, whereas 3 (3.8%) believed it is not important, and 9 (11.5%) remained undecided (Figure 1). Notably, 17 (21.8%) programs required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum, with most of these programs requiring 10 hours or less during the 3 years of residency training. Of the programs with required CS, 15 (88.2%) had dermatology-specific CS requirements, with 10 (58.8%) programs involved in CS at free and/or underserved clinics and some programs participating in other CS activities, such as advocacy, mentorship, educational outreach, or sports (Figure 2A).

Community service opportunities were offered to dermatology residents by 69 (88.5%) programs, including the 17 programs that required CS as part of the dermatology educational curriculum. Among these programs with optional CS, 43 (82.7%) PDs reported CS opportunities at free and/or underserved clinics, and 30 (57.7%) reported CS opportunities through global health initiatives (Figure 2B). Other CS opportunities offered included partnerships with community outreach organizations and mentoring underprivileged students. Patient populations that benefit from CS offered by these dermatology residency programs included 55 (79.7%) underserved, 33 (47.8%) minority, 31 (44.9%) immigrant, 14 (20.3%) pediatric, 14 (20.3%) elderly, and 10 (14.5%) rural populations (Figure 2C). At dermatology residency programs with optional CS opportunities, 22 (42.3%) PDs endorsed at least 50% of their residents participating in these activities.

Qualitative responses revealed that some PDs view CS as “a way for residents to stay connected to what drew them to medicine” and “essential to improving perceptions by physicians and patients about dermatology.” Program directors perceived lack of available time, initiative, and resources as well as minimal resident interest, malpractice coverage, and lack of educational opportunities as potential barriers to CS involvement by residents (Table). Forty-six (59.0%) PDs believed that CS should not be an ACGME requirement for dermatology training, 23 (29.5%) believed it should be required, and 9 (11.5%) were undecided.

Feedback From Residents—We received responses from 92 current dermatology residents and recent dermatology residency graduates; 86 (93.5%) respondents were trainees or recent graduates from academic dermatology residency training programs, and 6 (6.5%) were from community-based training programs. Community service was perceived to be an important part of dermatology training by 68 (73.9%) respondents, and dermatology-specific CS opportunities were available to 65 (70.7%) respondents (Figure 1). Although CS was required of only 7 (7.6%) respondents, 36 (39.1%) respondents volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during residency training. Among respondents who were not provided CS opportunities through their residency program, 23 (85.2%) stated they would have participated if given the opportunity.

Dermatology residents listed increased access to care for marginalized populations, increased sense of purpose, increased competence, and decreased burnout as perceived benefits of participation in CS. Of the dermatology residents who volunteered at a free dermatology clinic during training, 27 (75.0%) regarded the experience as a “high-yield learning opportunity.” Additionally, 29 (80.6%) residents stated their participation in a free dermatology clinic increased their awareness of health disparities and societal factors affecting dermatologic care in underserved patient populations. These respondents affirmed that their participation motivated them to become more involved in outreach targeting underserved populations throughout the duration of their careers.

Comment

The results of this nationwide survey have several important implications for dermatology residency programs, with a focus on programs in well-resourced and high socioeconomic status areas. Although most PDs believe that CS is important for dermatology resident training, few programs have CS requirements, and the majority are opposed to ACGME-mandated CS. Dermatology residents and recent graduates overwhelmingly conveyed that participation in a free dermatology clinic during residency training increased their knowledge base surrounding socioeconomic determinants of health and practicing in resource-limited settings. Furthermore, most trainees expressed that CS participation as a resident motivated them to continue to partake in CS for the underserved as an attending physician. The discordance between perceived value of CS by residents and the lack of CS requirements and opportunities by residency programs represents a realistic opportunity for residency training programs to integrate CS into the curriculum.

Residency programs that integrate service for the underserved into their program goals are 3 times more successful in graduating dermatology residents who practice in underserved communities.9 Patients in marginalized communities and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face many barriers to accessing dermatologic care including longer wait times and higher practice rejection rates than patients with private insurance.6 Through increased CS opportunities, dermatology residency programs can strengthen the local health care infrastructure and bridge the gap in access to dermatologic care.

By establishing a formal CS rotation in dermatology residency programs, residents will experience invaluable first-hand educational opportunities, provide comprehensive care for patients in resource-limited settings, and hopefully continue to serve in marginalized communities. Incorporating service for the underserved into the dermatology residency curriculum not only enhances the cultural competency of trainees but also mandates that skin health equity be made a priority. By exposing dermatology residents to the diverse patient populations often served by free clinics, residents will increase their knowledge of skin disease presentation in patients with darker skin tones, which has historically been deficient in medical education.10,11

The limitations of this survey study included recall bias, the response rate of PDs (54.9%), and the inability to determine response rate of residents, as we were unable to establish the total number of residents who received our survey. Based on geographic location, some dermatology residency programs may treat a high percentage of medically underserved patients, which already improves access to dermatology. For this reason, follow-up studies correlating PD and resident responses with region, program size, and university/community affiliation will increase our understanding of CS participation and perceptions.

Conclusion

Dermatology residency program participation in CS helps reduce barriers to access for patients in marginalized communities. Incorporating CS into the dermatology residency program curriculum creates a rewarding training environment that increases skin health equity, fosters an interest in health disparities, and enhances the cultural competency of its trainees.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

- Vaidya T, Zubritsky L, Alikhan A, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic barriers to dermatology care in urban and rural US populations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:406-408.

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307.

- Resneck J, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Resneck J, Pletcher MJ, Lozano N. Medicare, Medicaid, and access to dermatologists: the effect of patient insurance on appointment access and wait times. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:85-92.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Vance MC, Kennedy KG. Developing an advocacy curriculum: lessons learned from a national survey of psychiatric residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:283-288.

- Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:53-59.

- Vaidya T, Zubritsky L, Alikhan A, et al. Socioeconomic and geographic barriers to dermatology care in urban and rural US populations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:406-408.

- Suneja T, Smith ED, Chen GJ, et al. Waiting times to see a dermatologist are perceived as too long by dermatologists: implications for the dermatology workforce. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1303-1307.

- Resneck J, Kimball AB. The dermatology workforce shortage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:50-54.

- Yoo JY, Rigel DS. Trends in dermatology: geographic density of US dermatologists. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:779.

- Resneck J, Pletcher MJ, Lozano N. Medicare, Medicaid, and access to dermatologists: the effect of patient insurance on appointment access and wait times. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:85-92.

- Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, et al. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1286-1291.

- Vance MC, Kennedy KG. Developing an advocacy curriculum: lessons learned from a national survey of psychiatric residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:283-288.

- Blanco G, Vasquez R, Nezafati K, et al. How residency programs can foster practice for the underserved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:158-159.

- Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:687-690.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

Practice Points

- Participation of dermatology residents in service-learning experiences increases awareness of health disparities and social factors impacting dermatologic care and promotes a lifelong commitment to serving vulnerable populations.

- Integrating service learning into the dermatology residency program curriculum enhances trainees’ cultural sensitivity and encourages the prioritization of skin health equity.

- Service learning will help bridge the gap in access to dermatologic care for patients in medically marginalized communities.