User login

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

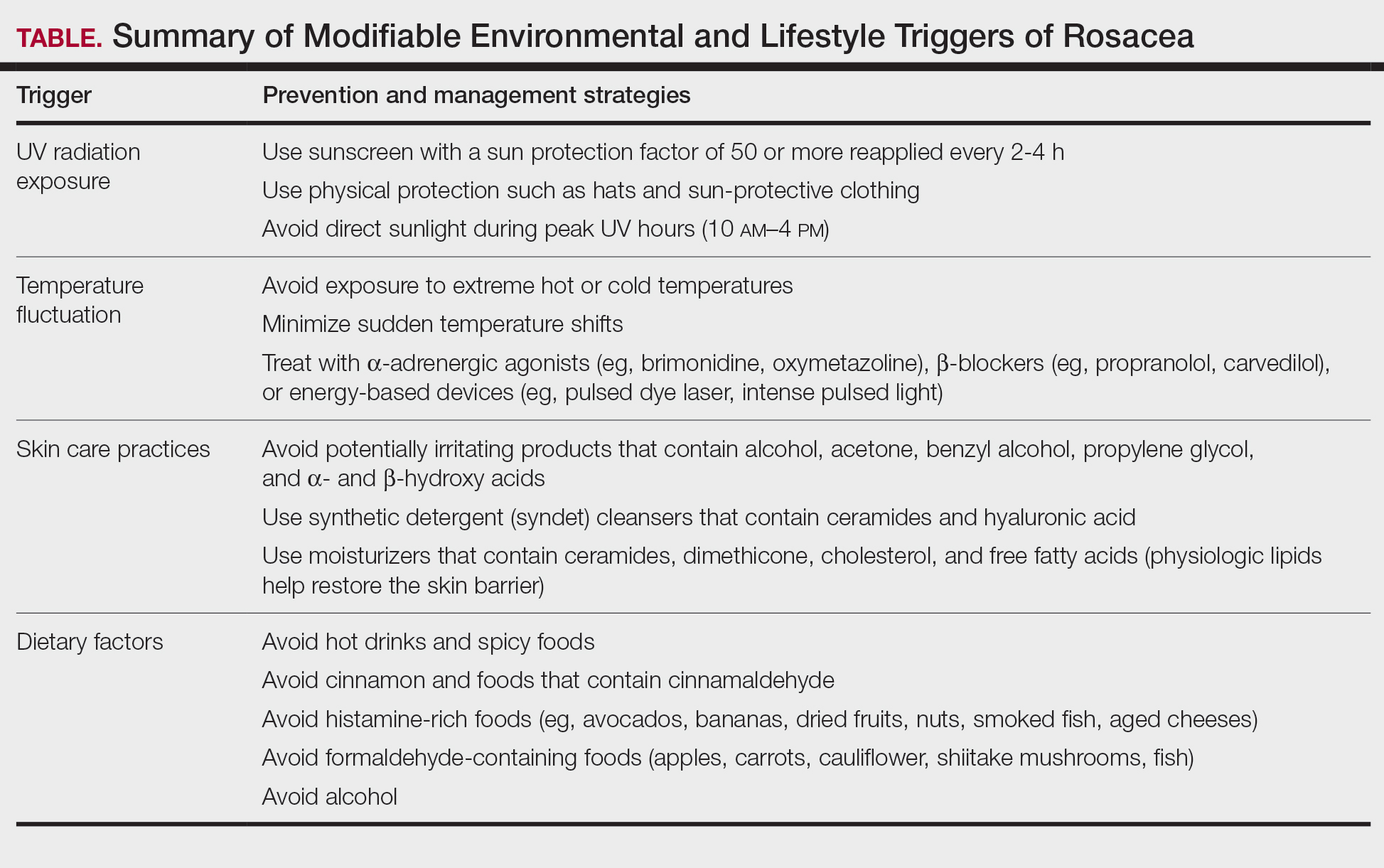

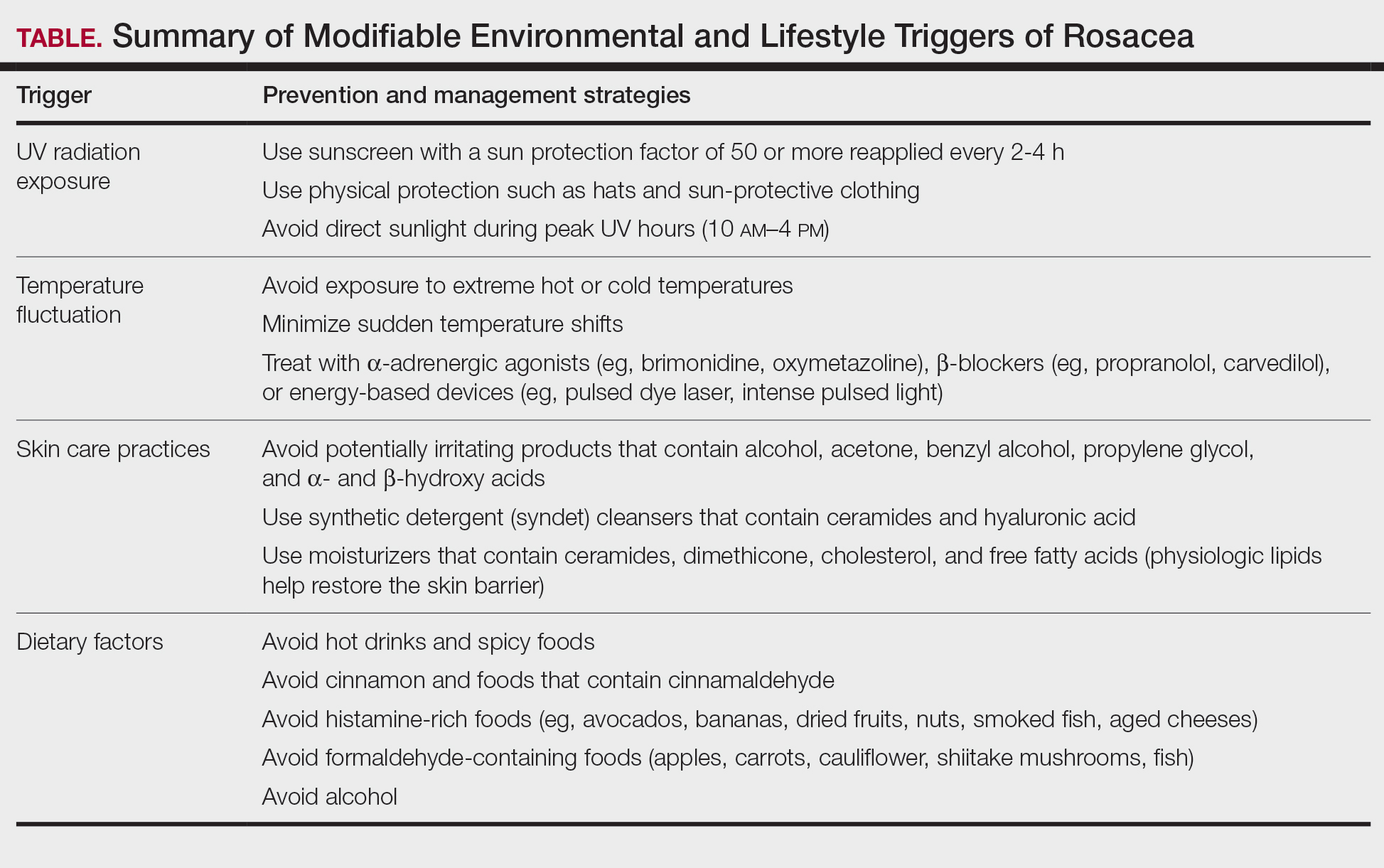

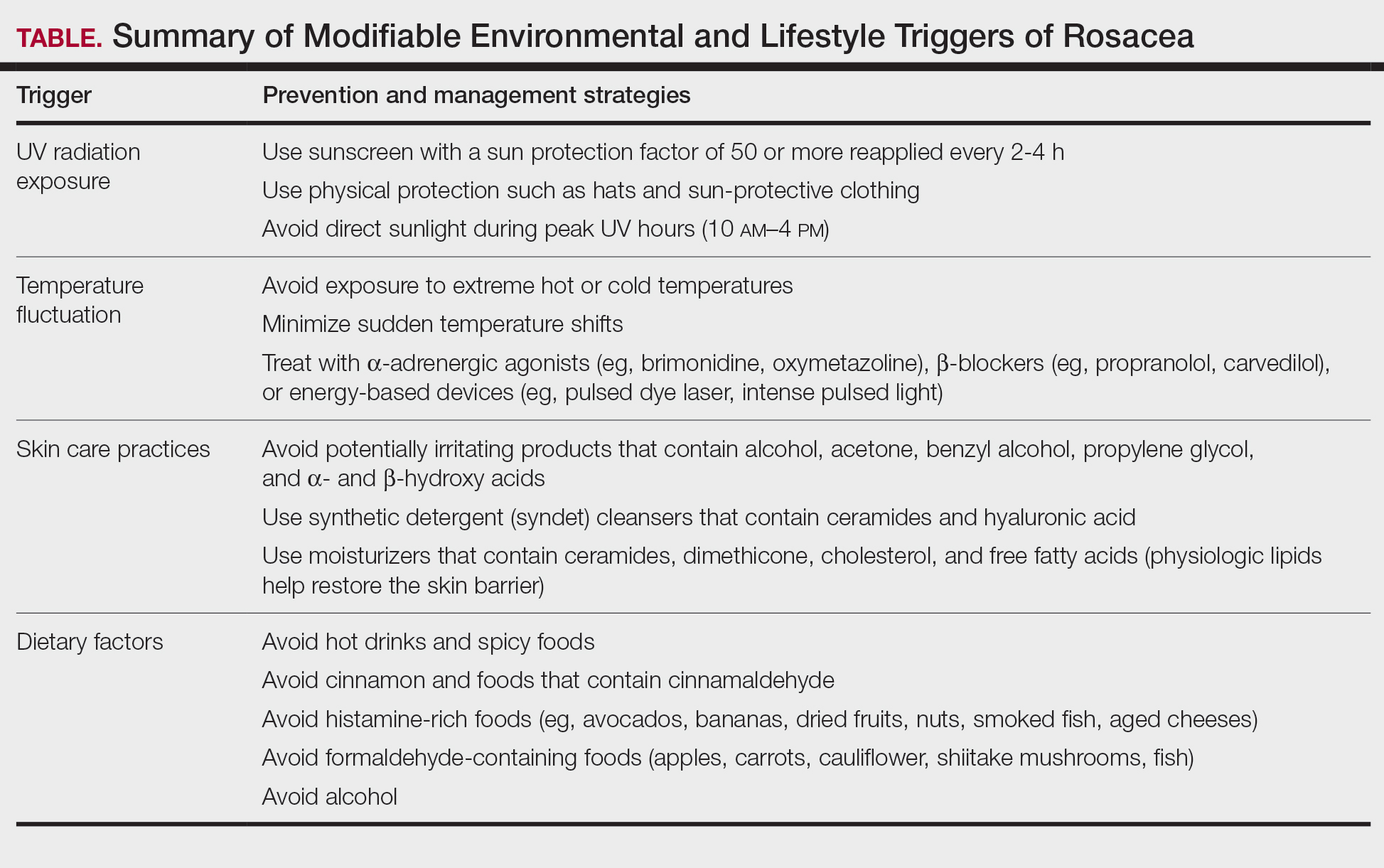

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

PRACTICE POINTS

- It is important to routinely assess and individualize rosacea management by encouraging use of symptom and trigger diaries to guide lifestyle modifications.

- Patients with rosacea should be encouraged to use mild, fragrance-free cleansers, barrier-supporting moisturizers, and daily broad-spectrum sunscreen and to avoid common irritants.

- Address flushing and erythema with behavioral and medical strategies; counsel patients on minimizing abrupt temperature shifts and consider topical Symbolα-adrenergic agonists, anti-inflammatory agents, or laser therapies when lifestyle measures alone are insufficient.

- Lifestyle recommendations (eg, optimal skin care practices, avoidance of dietary triggers) should be incorporated in treatment plans.