User login

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

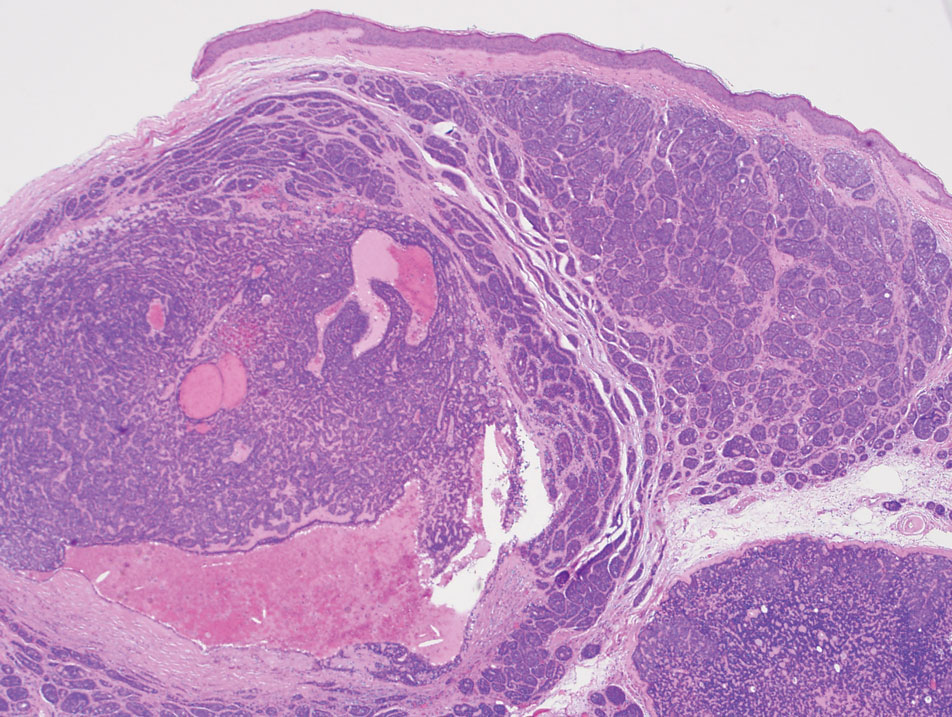

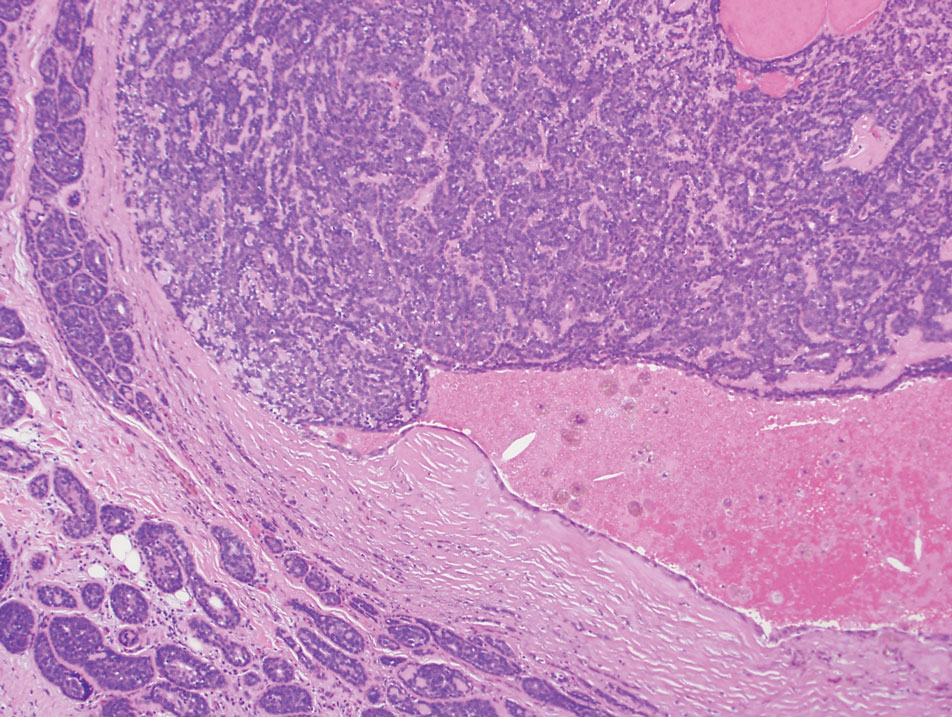

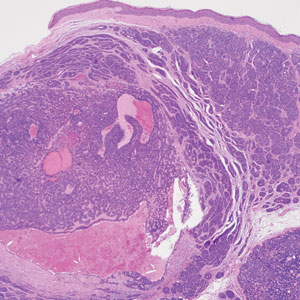

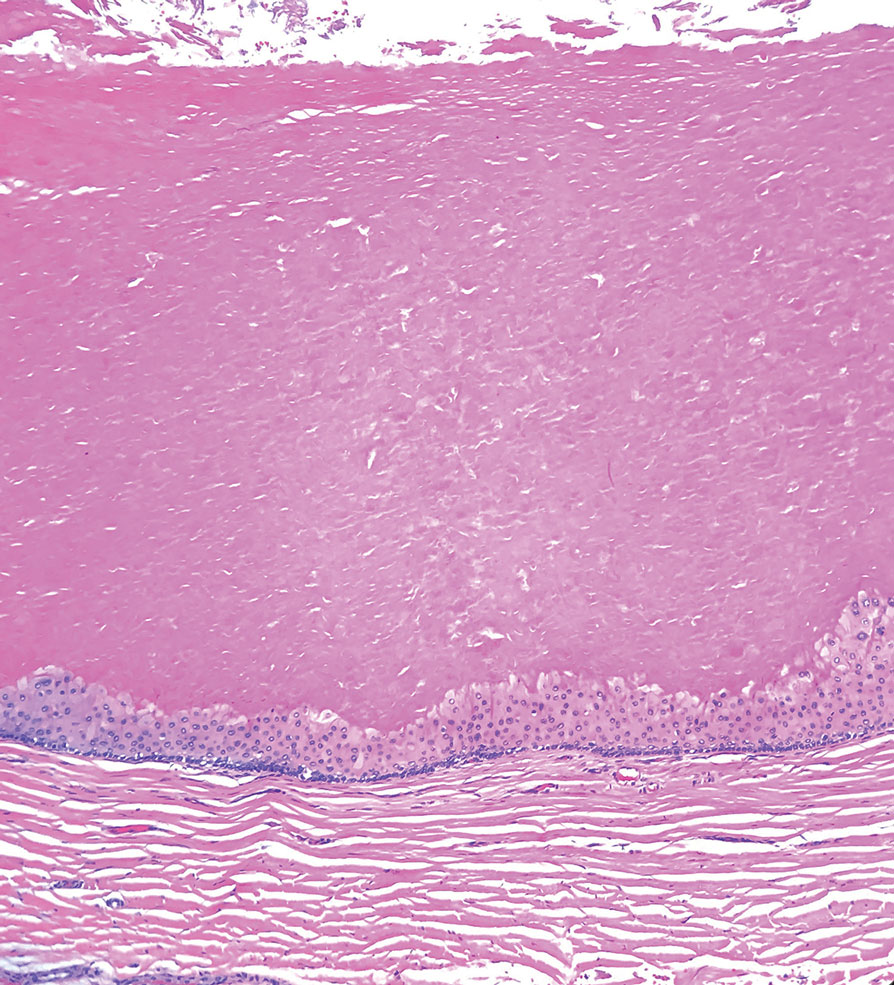

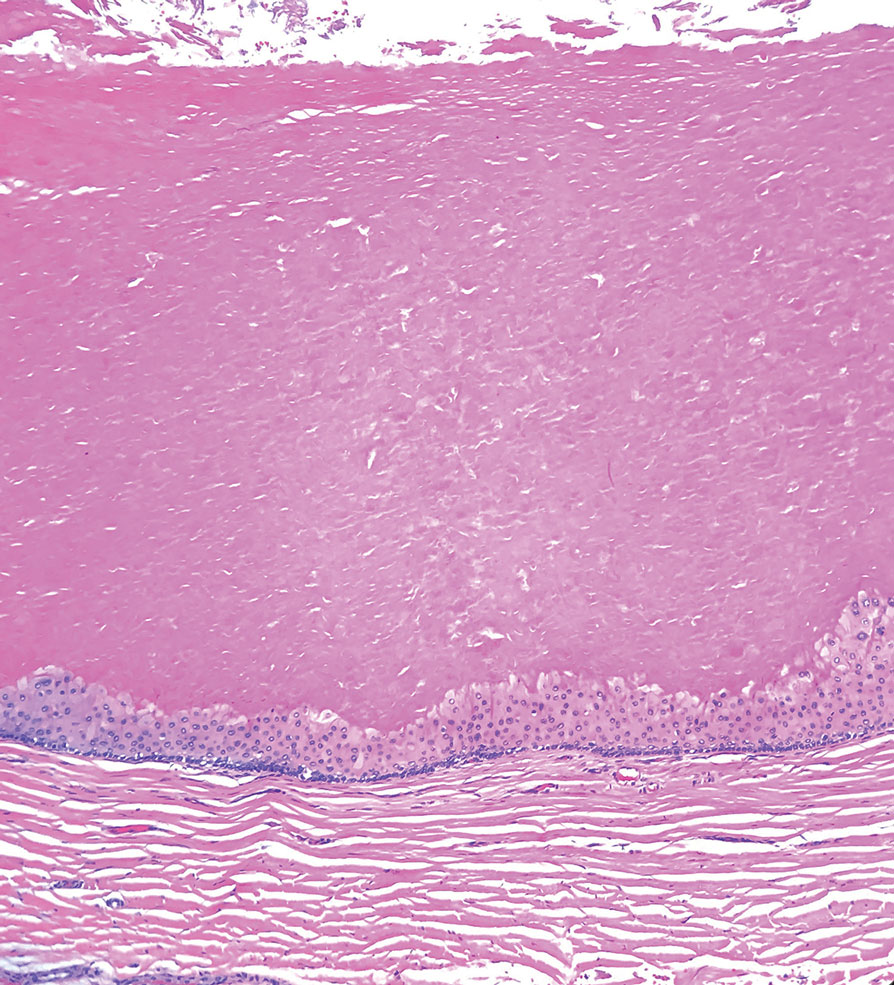

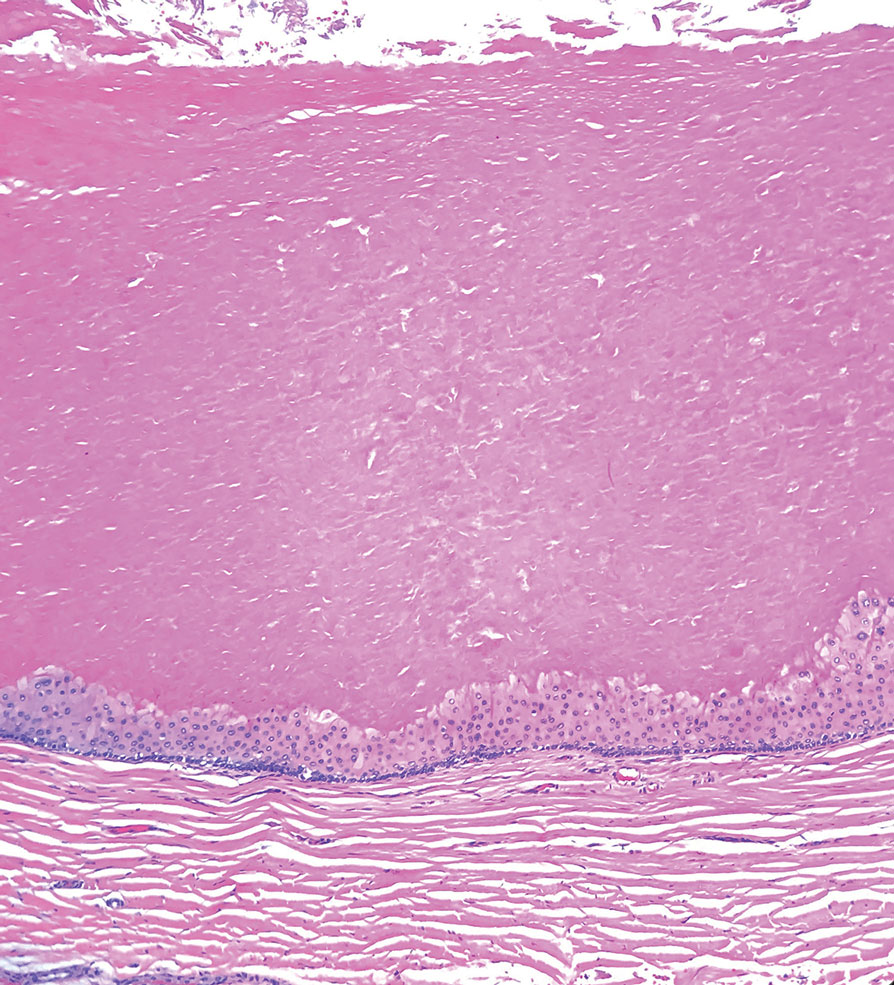

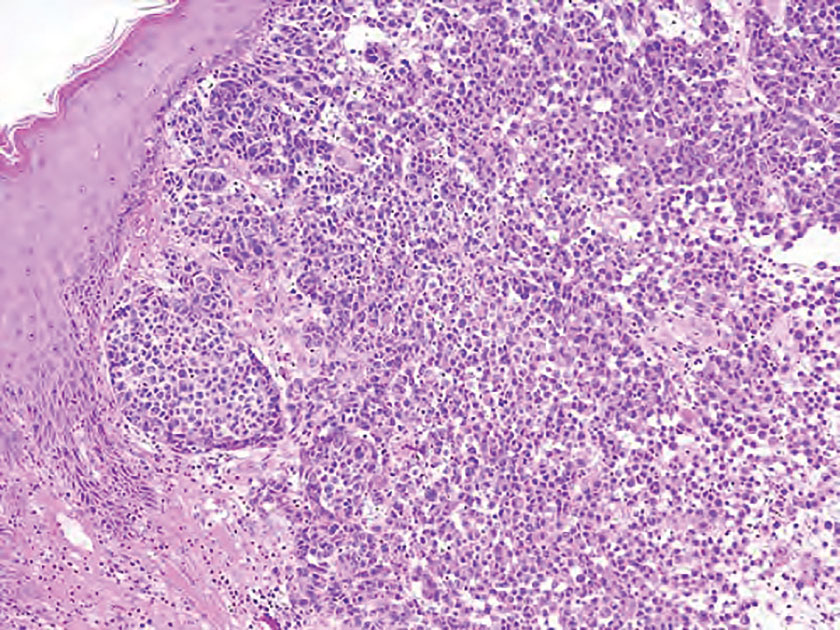

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

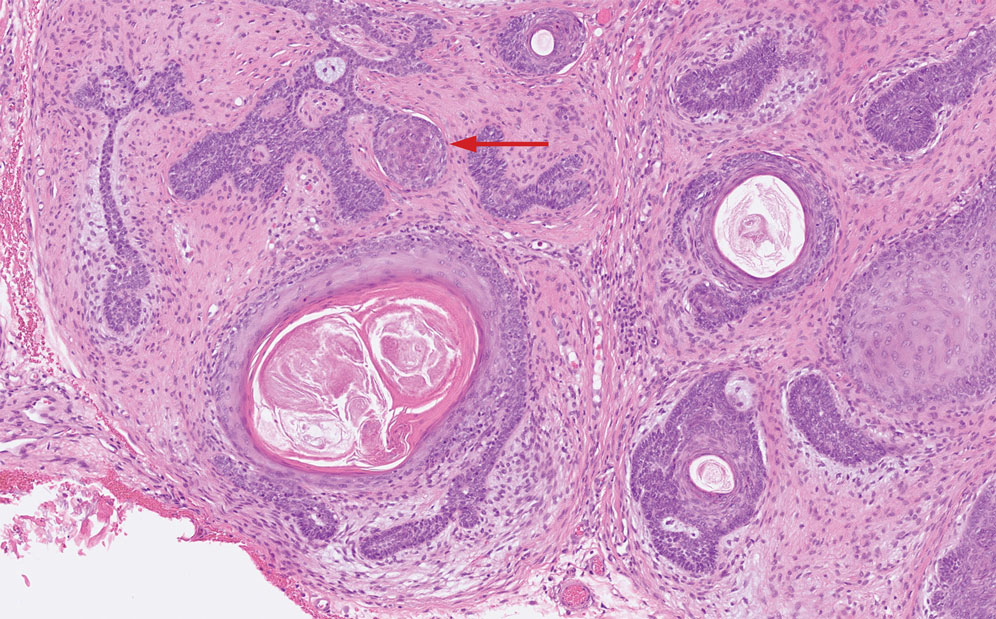

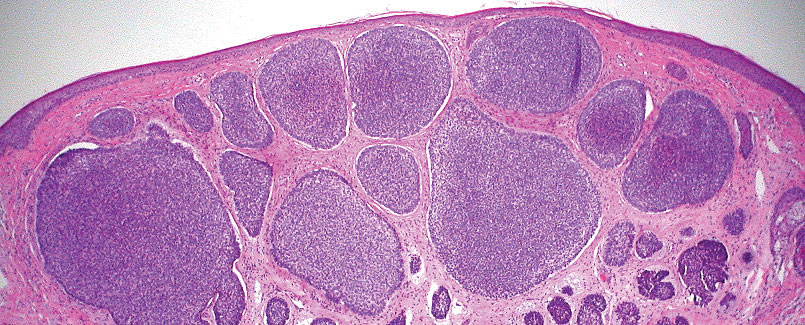

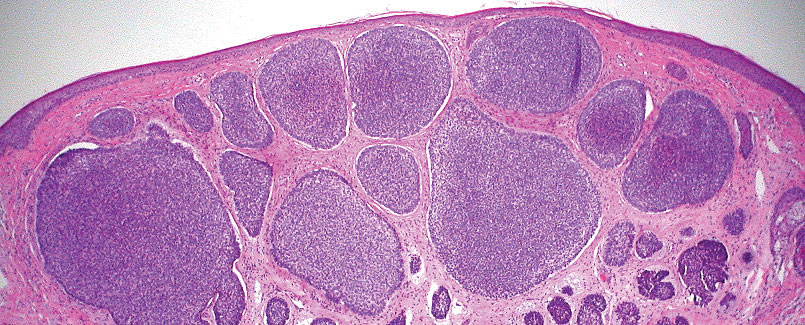

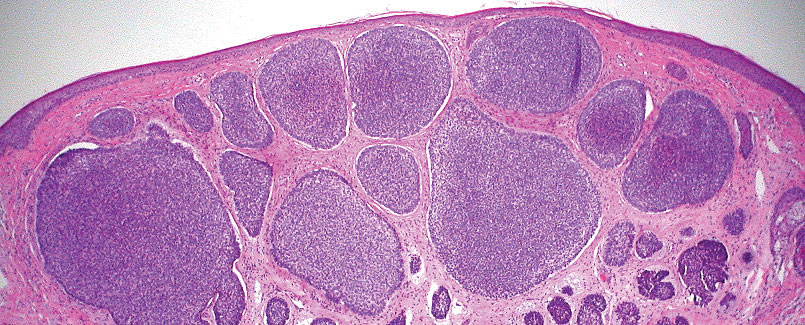

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

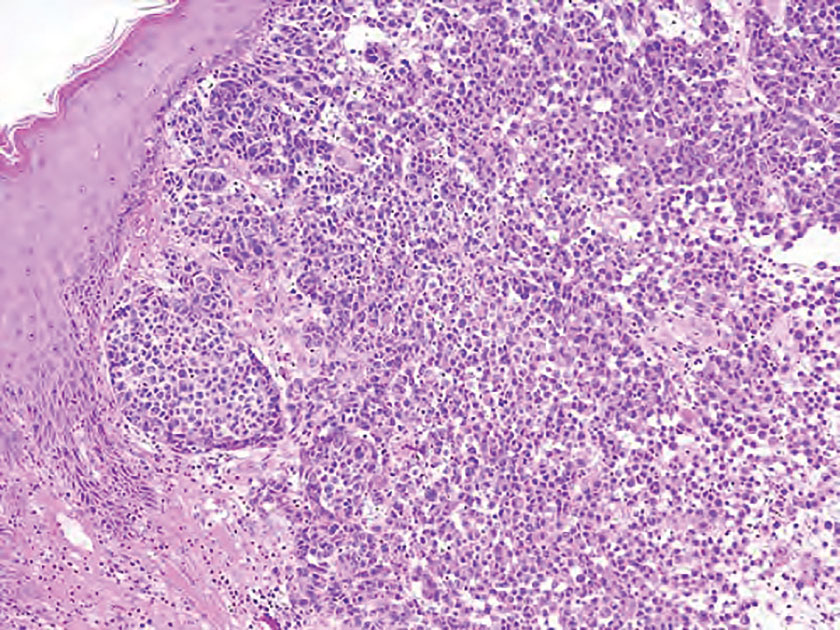

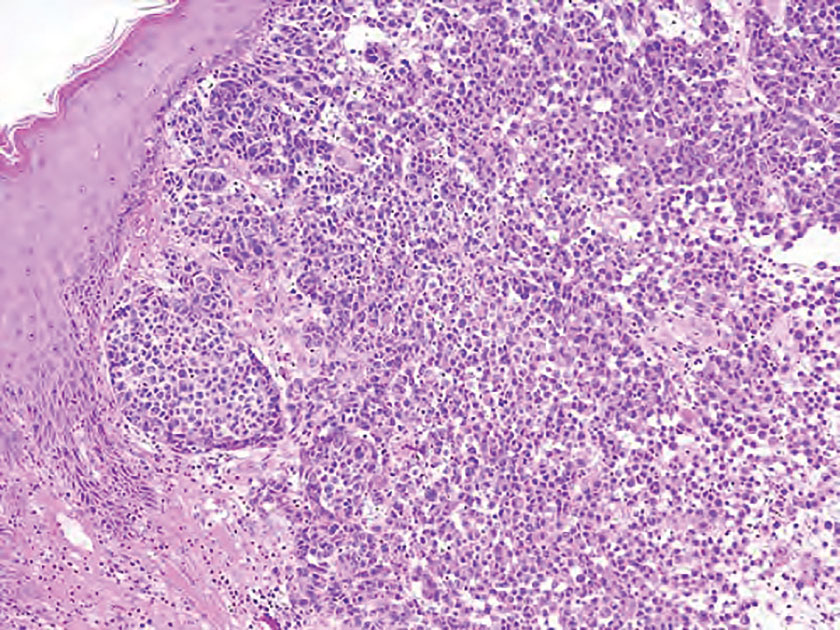

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

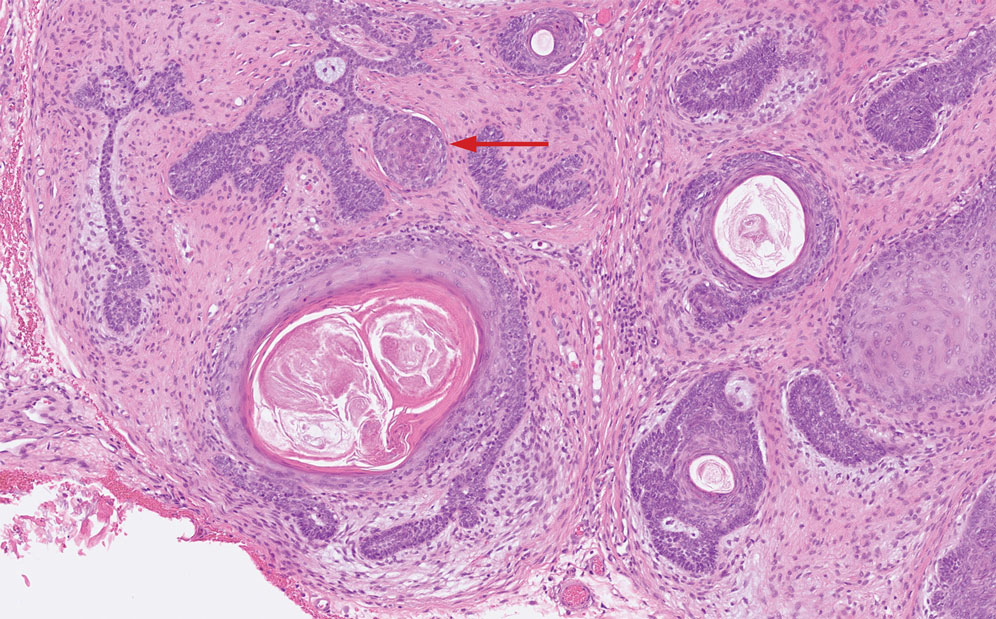

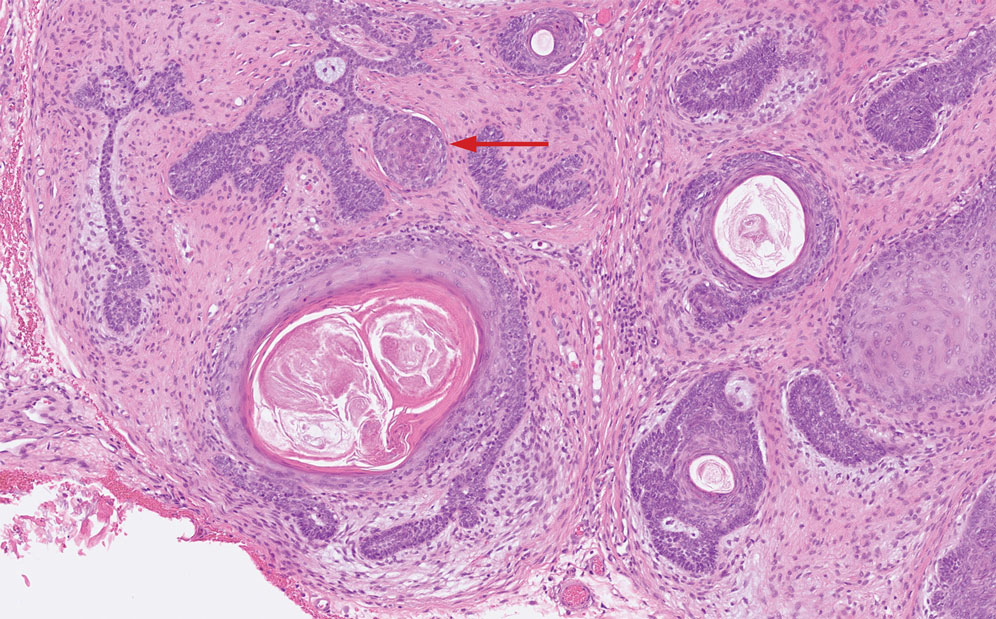

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

A 73-year-old man presented to the plastic surgery department with a single, progressively enlarging nodule on the scalp of 1 year’s duration. Dermatologic examination revealed a 0.8-cm, soft, mobile, gray-blue, dome-shaped papule on the left postauricular scalp that was tender to palpation. There was no central punctum, and the patient denied any history of drainage or odor. He had no personal or family history of similar lesions. An excisional biopsy of the papule was performed.