User login

Novel COVID-19 vaccine could fill the void for patients with blood cancers

according to study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The phase 1/2 trial included 54 patients with a B-cell deficiency (mean age, 63 years; 28% female): 4 had congenital B-cell deficiency and 50 had a blood cancer (lymphocytic leukemia or lymphoma). T-cell immune responses were observed in 86% of patients 28 days after vaccination with a single CoVac-1 dose. The potency of CoVac-1–induced T-cell responses exceeded those seen typically with B cell–deficient patient responses after mRNA vaccine treatment and were comparable with those seen among nonimmunocompromised COVID-19 patients.

In the majority of individuals, currently approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccines induce a robust immune response, however, their efficacy, has been shown to be decreased among individuals who are immunocompromised. Patients treated for hematologic cancers, in particular, receive treatment regimens that damage healthy immune cells, particularly B cells, said Juliane Walz, MD, the study’s senior author and professor of medicine at University Hospital Tübingen (Germany).

“In the clinic, we see many cancer patients who do not mount sufficient humoral immune responses after vaccination with available SARS-CoV-2 vaccines,” Dr. Walz said. “These patients are at a high risk for a severe course of COVID-19.”

B-cell deficiency, she stated, can be compensated for by enhancing T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2, which can then combat infections in the absence of neutralizing antibodies.

In a prior study of CoVac-1 among 36 adults without immune deficiency, the vaccine elicited T-cell responses that were still robust 3 months post vaccination, and that included responses against omicron and other key SARS-CoV-2 variants.

While mRNA-based or adenoviral vector-based vaccines are limited to the spike protein and are thus prone to loss of activity because of viral mutations, CoVac-1–induced T-cell immunity is far more intense and broader, Dr. Walz said.

CoVac-1 is a peptide vaccine that is injected directly rather than being encoded via mRNA and targets different viral components. It would not be given, however, to healthy, immunocompetent adults because it is important for them to have both B-cell antibody and T-cell response.

The patients with B-cell deficiency recruited for the study were given a single dose of CoVac-1 and assessed for safety and immunogenicity until day 56. Prior vaccinations with an approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine had failed to elicit a humoral response in 87% of the subjects.

“Our vaccine does not induce antibody responses,” Dr. Walz said. “However, it could be used to induce broad T-cell responses as a complementary or additive vaccine for elderly adults. In the elderly, antibody responses decline very, very fast after vaccination.”

Dr. Walz said that CoVac-1 could find application in various syndromes associated with congenital B-cell deficiencies, in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, or diseases treated with rituximab or other B cell–depleting therapies (for example, ofatumumab, blinatumomab, or chimeric antigen receptor T cells), and in transplant patients.

A phase 3 study of CoVac-1 versus placebo is under discussion and would require about 300-500 subjects, Dr. Walz said.

“CoVac-1 is designed to induce broad and long-lasting SARS-CoV-2 T-cell immunity, even in individuals who have impaired ability to mount sufficient immunity from a currently approved vaccine, and thus protect these high-risk patients from a severe course of COVID-19,” Dr. Walz said.

“Having an option for these patients is just critical – so this is significant work,” said Ana Maria Lopez, MD, MPH, of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center–Jefferson Health, Philadelphia.

Limitations of this study included the small sample size with low racial and ethnic diversity, Dr. Walz stated.

Funding was provided by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of the state of Baden-Württemberg; the Federal Ministry of Research and Education in Germany; the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy; and the Clinical Cooperation Unit Translational Immunology at University Hospital Tübingen. Dr. Walz holds the CoVac-1 patent.

according to study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The phase 1/2 trial included 54 patients with a B-cell deficiency (mean age, 63 years; 28% female): 4 had congenital B-cell deficiency and 50 had a blood cancer (lymphocytic leukemia or lymphoma). T-cell immune responses were observed in 86% of patients 28 days after vaccination with a single CoVac-1 dose. The potency of CoVac-1–induced T-cell responses exceeded those seen typically with B cell–deficient patient responses after mRNA vaccine treatment and were comparable with those seen among nonimmunocompromised COVID-19 patients.

In the majority of individuals, currently approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccines induce a robust immune response, however, their efficacy, has been shown to be decreased among individuals who are immunocompromised. Patients treated for hematologic cancers, in particular, receive treatment regimens that damage healthy immune cells, particularly B cells, said Juliane Walz, MD, the study’s senior author and professor of medicine at University Hospital Tübingen (Germany).

“In the clinic, we see many cancer patients who do not mount sufficient humoral immune responses after vaccination with available SARS-CoV-2 vaccines,” Dr. Walz said. “These patients are at a high risk for a severe course of COVID-19.”

B-cell deficiency, she stated, can be compensated for by enhancing T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2, which can then combat infections in the absence of neutralizing antibodies.

In a prior study of CoVac-1 among 36 adults without immune deficiency, the vaccine elicited T-cell responses that were still robust 3 months post vaccination, and that included responses against omicron and other key SARS-CoV-2 variants.

While mRNA-based or adenoviral vector-based vaccines are limited to the spike protein and are thus prone to loss of activity because of viral mutations, CoVac-1–induced T-cell immunity is far more intense and broader, Dr. Walz said.

CoVac-1 is a peptide vaccine that is injected directly rather than being encoded via mRNA and targets different viral components. It would not be given, however, to healthy, immunocompetent adults because it is important for them to have both B-cell antibody and T-cell response.

The patients with B-cell deficiency recruited for the study were given a single dose of CoVac-1 and assessed for safety and immunogenicity until day 56. Prior vaccinations with an approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine had failed to elicit a humoral response in 87% of the subjects.

“Our vaccine does not induce antibody responses,” Dr. Walz said. “However, it could be used to induce broad T-cell responses as a complementary or additive vaccine for elderly adults. In the elderly, antibody responses decline very, very fast after vaccination.”

Dr. Walz said that CoVac-1 could find application in various syndromes associated with congenital B-cell deficiencies, in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, or diseases treated with rituximab or other B cell–depleting therapies (for example, ofatumumab, blinatumomab, or chimeric antigen receptor T cells), and in transplant patients.

A phase 3 study of CoVac-1 versus placebo is under discussion and would require about 300-500 subjects, Dr. Walz said.

“CoVac-1 is designed to induce broad and long-lasting SARS-CoV-2 T-cell immunity, even in individuals who have impaired ability to mount sufficient immunity from a currently approved vaccine, and thus protect these high-risk patients from a severe course of COVID-19,” Dr. Walz said.

“Having an option for these patients is just critical – so this is significant work,” said Ana Maria Lopez, MD, MPH, of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center–Jefferson Health, Philadelphia.

Limitations of this study included the small sample size with low racial and ethnic diversity, Dr. Walz stated.

Funding was provided by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of the state of Baden-Württemberg; the Federal Ministry of Research and Education in Germany; the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy; and the Clinical Cooperation Unit Translational Immunology at University Hospital Tübingen. Dr. Walz holds the CoVac-1 patent.

according to study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The phase 1/2 trial included 54 patients with a B-cell deficiency (mean age, 63 years; 28% female): 4 had congenital B-cell deficiency and 50 had a blood cancer (lymphocytic leukemia or lymphoma). T-cell immune responses were observed in 86% of patients 28 days after vaccination with a single CoVac-1 dose. The potency of CoVac-1–induced T-cell responses exceeded those seen typically with B cell–deficient patient responses after mRNA vaccine treatment and were comparable with those seen among nonimmunocompromised COVID-19 patients.

In the majority of individuals, currently approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccines induce a robust immune response, however, their efficacy, has been shown to be decreased among individuals who are immunocompromised. Patients treated for hematologic cancers, in particular, receive treatment regimens that damage healthy immune cells, particularly B cells, said Juliane Walz, MD, the study’s senior author and professor of medicine at University Hospital Tübingen (Germany).

“In the clinic, we see many cancer patients who do not mount sufficient humoral immune responses after vaccination with available SARS-CoV-2 vaccines,” Dr. Walz said. “These patients are at a high risk for a severe course of COVID-19.”

B-cell deficiency, she stated, can be compensated for by enhancing T-cell responses against SARS-CoV-2, which can then combat infections in the absence of neutralizing antibodies.

In a prior study of CoVac-1 among 36 adults without immune deficiency, the vaccine elicited T-cell responses that were still robust 3 months post vaccination, and that included responses against omicron and other key SARS-CoV-2 variants.

While mRNA-based or adenoviral vector-based vaccines are limited to the spike protein and are thus prone to loss of activity because of viral mutations, CoVac-1–induced T-cell immunity is far more intense and broader, Dr. Walz said.

CoVac-1 is a peptide vaccine that is injected directly rather than being encoded via mRNA and targets different viral components. It would not be given, however, to healthy, immunocompetent adults because it is important for them to have both B-cell antibody and T-cell response.

The patients with B-cell deficiency recruited for the study were given a single dose of CoVac-1 and assessed for safety and immunogenicity until day 56. Prior vaccinations with an approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine had failed to elicit a humoral response in 87% of the subjects.

“Our vaccine does not induce antibody responses,” Dr. Walz said. “However, it could be used to induce broad T-cell responses as a complementary or additive vaccine for elderly adults. In the elderly, antibody responses decline very, very fast after vaccination.”

Dr. Walz said that CoVac-1 could find application in various syndromes associated with congenital B-cell deficiencies, in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis, or diseases treated with rituximab or other B cell–depleting therapies (for example, ofatumumab, blinatumomab, or chimeric antigen receptor T cells), and in transplant patients.

A phase 3 study of CoVac-1 versus placebo is under discussion and would require about 300-500 subjects, Dr. Walz said.

“CoVac-1 is designed to induce broad and long-lasting SARS-CoV-2 T-cell immunity, even in individuals who have impaired ability to mount sufficient immunity from a currently approved vaccine, and thus protect these high-risk patients from a severe course of COVID-19,” Dr. Walz said.

“Having an option for these patients is just critical – so this is significant work,” said Ana Maria Lopez, MD, MPH, of the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center–Jefferson Health, Philadelphia.

Limitations of this study included the small sample size with low racial and ethnic diversity, Dr. Walz stated.

Funding was provided by the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of the state of Baden-Württemberg; the Federal Ministry of Research and Education in Germany; the German Research Foundation under Germany’s Excellence Strategy; and the Clinical Cooperation Unit Translational Immunology at University Hospital Tübingen. Dr. Walz holds the CoVac-1 patent.

FROM AACR 2022

Neutropenia and Leukopenia After Cross Taper From Quetiapine to Divalproex for the Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivative, divalproex (DVP) are prescribed for a variety of indications, commonly for seizure control in patients with epilepsy, mood stabilization in patients with bipolar disorder, and migraine prophylaxis. Gastrointestinal distress and sedation are among the most reported adverse effects (AEs) with DVP therapy.1 Although serious hepatic and hematologic AEs are rare, monitoring is still recommended. DVP can cause various hematologic dyscrasias, the most common being thrombocytopenia.1,2 Neutropenia and leukopenia have been reported in isolated cases, most occurring in pediatric patients or patients with epilepsy.3-14

Several case reports of DVP-related neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 1.50 103/mcL) and leukopenia (white blood cell count [WBC] < 4.0 103/mcL) were reviewed during our literature search, some caused by DVP monotherapy; others were thought to be related to concomitant use of DVP and another drug.15-25 Quetiapine was the antipsychotic most commonly implicated in causing hematologic abnormalities when combined with DVP. We report a case of neutropenia and leukopenia that presented after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP for the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Although no medications have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have literature to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 A therapeutic range for DVP in the treatment of BPD has not been defined; therefore, for this case report, the generally accepted range of 50 to 100 µg/mL will be considered therapeutic.1

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient presented to the mental health clinic pharmacist reporting that his current psychotropic medication regimen was not effective. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, cannabis use, BPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prediabetes, gastroesophageal reflex disease, and a pulmonary nodule. On initial presentation, the patient was prescribed buprenorphine 24 mg/naloxone 6 mg, quetiapine 400 mg, duloxetine 120 mg, and prazosin 15 mg per day. At the time of pharmacy consultation, last reported alcohol or nonprescribed opioid use was about 6 months prior, and methamphetamine use about 1 month prior, with ongoing cannabis use. The patient had a history of participating in cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and residential treatment for both PTSD and substance use. Additionally, he was actively participating in contingency management for stimulant use disorder and self-management and recovery training group.

The patient reported ongoing mood lability, hypervigilance, and oversedation with current psychotropic regimen. The prescriber of his medication for opioid use disorder also reported the patient experienced labile mood, impulsive behavior, and anger outbursts. In the setting of intolerability due to oversedation with quetiapine, cardiometabolic risk, and lack of clear indication for use, the patient and health care practitioner (HCP) agreed to taper quetiapine and initiate a trial of DVP for affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol. To prevent cholinergic rebound and insomnia with abrupt discontinuation of quetiapine, DVP and quetiapine were cross tapered. The following cross taper was prescribed: quetiapine 300 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 1; quetiapine 200 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 2; quetiapine 100 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 3; quetiapine 50 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 4; followed by DVP 1000 mg per day and discontinuation of quetiapine.

During a 4-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported appropriate completion of cross taper but stopped taking the DVP 3 days prior to the appointment due to self-reported lack of efficacy. For this reason, serum VPA level was not obtained. After discussion with his HCP, the patient restarted DVP 1000 mg per day without retitration with plans to get laboratory tests in 1 week. The next week, laboratory tests were notable for VPA level 28.74 (reference range, 50-100) µg/mL, low WBC 3.51 (reference range, 4.00-10.00) 103/mcL, platelets 169 (reference range, 150-420) 103/mcL, and low ANC 1.00 (reference range, 1.50-7.40) 103/mcL (Table). This raised clinical concern as the patient had no history of documented neutropenia or leukopenia, with most recent complete blood count (CBC) prior to DVP initiation 3 months earlier while prescribed quetiapine.

On further review, the HCP opted to cease administration of DVP and repeat CBC with differential in 1 week. Nine days later, laboratory tests were performed and compared with those collected the week before, revealing resolution of neutropenia and leukopenia. A score of 7 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (NADRPS) was determined based on previous conclusive reports on the reaction (+1), appeared after suspected drug administration (+2), improved with drug discontinuation (+1), confirmed by objective evidence (+1), and no alternative causes could be found (+2).29 With a NADRPS score of 7, an AE of probable DVP-induced neutropenia was documented and medication was not resumed.

Discussion

Our case report describes isolated neutropenia and leukopenia that developed after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP. Hematologic abnormalities resolved after discontinuation of DVP, suggesting a likely correlation. DVP has a well-established, dose-related prevalence of thrombocytopenia occurring in up to 27% of patients.1 Fewer case reports exist on neutropenia and leukopenia. DVP-induced neutropenia is thought to be a result of direct bone marrow suppression, whereas the more commonly occurring blood dyscrasia, thrombocytopenia, is thought to be caused by an antibody-mediated destruction of platelets.6

Management of DVP-induced thrombocytopenia is often dependent on the severity of the reaction. In mild-to-moderate cases, intervention may not be necessary as thrombocytopenia has been shown to resolve without adjustment to DVP therapy.1 In more severe or symptomatic cases, dose reduction or discontinuation of the offending agent is recommended, typically resulting in resolution shortly following pharmacologic intervention.

Guidance on the management of other drug-induced hematologic abnormalities, such as neutropenia and leukopenia are not as well established. A 2019 systematic review of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia suggested that continuing the offending drug with strict monitoring could be considered in cases of mild neutropenia. In cases of moderate neutropenia, the author suggests temporary cessation of the drug and reinstatement once neutrophil count normalizes and definitive cessation of the drug in severe cases.30

In our case, continuing the offending agent with close monitoring was considered, similar to the well-established management of clozapine-induced neutropenia. However, due to the concern that the ANC was bordering moderate neutropenia in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level as well as a significant reduction in platelets, although not meeting criteria for thrombocytopenia, the decision was made to err on the side of caution and discontinue the most likely offending agent.

It is important to highlight that DVP was replacing quetiapine in the form of a cross taper. Quetiapine is structurally similar to clozapine. While clozapine has strict monitoring requirements related to neutropenia, blood dyscrasias with quetiapine therapy are rare. Quetiapine-induced hematologic abnormalities may be due to direct toxicity or to an immune-mediated mechanism, leading to bone marrow suppression.20 Case reports documenting blood dyscrasias with the combination of DVP and quetiapine were identified during literature review.15-19 Despite these case reports, we believe DVP was the primary offending agent in our case as the patient’s last dose of quetiapine was 2 weeks before obtaining the abnormal CBC. There was no history of blood dyscrasias with quetiapine monotherapy; however, the effect of the combination of DVP and quetiapine is unknown as no CBC was obtained during the cross-taper period.

Although there are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have some research to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 In our case, DVP was selected due to the evidence for use in BPD and ability to assess adherence with therapeutic monitoring. Although polypharmacy is a concern in patients with BPD, in our case we believed that the patient’s ongoing mood lability and impulsive behaviors warranted pharmacologic intervention. Additionally, DVP provided an advantage in its ability to quickly titrate to therapeutic dose when compared with lamotrigine and a lower risk of cognitive AEs when compared with topiramate.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this case report demonstrates the first published case of neutropenia and leukopenia related to DVP therapy for the treatment of BPD. Routine CBC monitoring is recommended with DVP therapy, and our case highlights the importance of evaluating for not only thrombocytopenia, but also other blood dyscrasias during the titration phase even in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level. Further studies are warranted to determine incidence of DVP-related neutropenia and leukopenia and to evaluate the safety of continuing DVP in cases of mild-to-moderate neutropenia with close monitoring.

1. Depakote (valproic acid). Package insert. Abbott Laboratories; June 2000.

2. Conley EL, Coley KC, Pollock BG, Dapos SV, Maxwell R, Branch RA. Prevalence and risk of thrombocytopenia with valproic acid: experience at a psychiatric teaching hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1325-1330. doi:10.1592/phco.21.17.1325.34418

3. Jaeken J, van Goethem C, Casaer P, Devlieger H, Eggermont E, Pilet M. Neutropenia during sodium valproate therapy. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54(12):986-987. doi:10.1136/adc.54.12.986

4. Barr RD, Copeland SA, Stockwell MC, Morris N, Kelton JC. Valproic acid and immune thrombocytopenia. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(9):681-684. doi:10.1136/adc.57.9.681

5. Symon DNK, Russell G. Sodium valproate and neutropenia (letter). Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:235. doi:10.1136/adc.58.3.235

6. Watts RG, Emanuel PD, Zuckerman KS, Howard TH. Valproic acid-induced cytopenias: evidence for a dose-related suppression of hematopoiesis. J Pediatr. 1990;117(3):495-499. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81105-9

7. Blackburn SC, Oliart AD, García-Rodríguez LA, Pérez Gutthann S. Antiepileptics and blood dyscrasias: a cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18(6):1277-1283.

8. Acharya S, Bussel JB. Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(1):62-65. doi:10.1097/00043426-200001000-00012

9. Vesta KS, Medina PJ. Valproic acid-induced neutropenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(6):819-821. doi:10.1345/aph.1C381

10. Kohli U, Gulati, S. Sodium valproate induced isolated neutropenia. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(9):844-844. doi:10.1007/BF02790401

11. Hsu HC, Tseng HK, Wang SC, Wang YY. Valproic acid-induced agranulocytosis. Int J Gerontol. 2009;3(2):137-139. doi:10.1016/S1873-9598(09)70036-5

12. Chakraborty S, Chakraborty J, Mandal S, Ghosal MK. A rare occurrence of isolated neutropenia with valproic acid: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109(5):345-346.

13. Stoner SC, Deal E, Lurk JT. Delayed-onset neutropenia with divalproex sodium. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(10):1507-1510. doi:10.1345/aph.1L239

14. Storch DD. Severe leukopenia with valproate. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1208-1209. doi:10.1097/00004583-200010000-00003

15. Rahman A, Mican LM, Fischer C, Campbell AH. Evaluating the incidence of leukopenia and neutropenia with valproate, quetiapine, or the combination in children and adolescents. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:822-830. doi:10.1345/aph.1L617

16. Hung WC, Hsieh MH. Neutropenia associated with the comedication of quetiapine and valproate in 2 elderly patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):416-417. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182549d2d

17. Park HJ, Kim JY. Incidence of neutropenia with valproate and quetiapine combination treatment in subjects with acquired brain injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(2):183-188. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.09.004

18. Estabrook KR, Pheister M. A case of quetiapine XR and divalproex-associated neutropenia followed by successful use of ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):417-418. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318253a071

19. Nair P, Lippmann S. Is leukopenia associated with divalproex and/or quetiapine? Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):188-189. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.188

20. Cowan C, Oakley C. Leukopenia and neutropenia induced by quetiapine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):292-294. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.07.003

21. Fan KY, Chen WY, Huang MC. Quetiapine-associated leucopenia and thrombocytopenia: a case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:110. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0495-9

22. Malik S, Lally J, Ajnakina O, et al. Sodium valproate and clozapine induced neutropenia: A case control study using register data. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:267-273. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.041

23. Pantelis C, Adesanya A. Increased risk of neutropaenia and agranulocytosis with sodium valproate used adjunctively with clozapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(4):544-545. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.0911f.x

24. Madeb R, Hirschmann S, Kurs R, Turkie A, Modai I. Combined clozapine and valproic acid treatment-induced agranulocytosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):238-239. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00659-4

25. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, Theison M, Emrich HM. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31(4):122-125. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979312

26. Ingenhoven T, Lafay P, Rinne T, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden H. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for severe personality disorders: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:14. doi:10.4088/jcp.08r04526gre

27. Mercer D, Douglass AB, Links PS. Meta-analyses of mood stabilizers, antidepressants and antipsychotics in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: effectiveness for depression and anger symptoms. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(2):156-174. doi:10.1521/pedi.2009.23.2.156

28. Hollander E, Swann AC, Coccaro EF, Jiang P, Smith TB. Impact of trait impulsivity and state aggression on divalproex versus placebo response in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):621-624. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.621

29. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.154

30. Andrès E, Villalba NL, Zulfiqar AA, Serraj K, Mourot-Cottet R, Gottenberg AJ. State of art of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia or agranulocytosis, with a focus on biotherapies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1351. doi:10.3390/jcm8091351

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivative, divalproex (DVP) are prescribed for a variety of indications, commonly for seizure control in patients with epilepsy, mood stabilization in patients with bipolar disorder, and migraine prophylaxis. Gastrointestinal distress and sedation are among the most reported adverse effects (AEs) with DVP therapy.1 Although serious hepatic and hematologic AEs are rare, monitoring is still recommended. DVP can cause various hematologic dyscrasias, the most common being thrombocytopenia.1,2 Neutropenia and leukopenia have been reported in isolated cases, most occurring in pediatric patients or patients with epilepsy.3-14

Several case reports of DVP-related neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 1.50 103/mcL) and leukopenia (white blood cell count [WBC] < 4.0 103/mcL) were reviewed during our literature search, some caused by DVP monotherapy; others were thought to be related to concomitant use of DVP and another drug.15-25 Quetiapine was the antipsychotic most commonly implicated in causing hematologic abnormalities when combined with DVP. We report a case of neutropenia and leukopenia that presented after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP for the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Although no medications have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have literature to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 A therapeutic range for DVP in the treatment of BPD has not been defined; therefore, for this case report, the generally accepted range of 50 to 100 µg/mL will be considered therapeutic.1

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient presented to the mental health clinic pharmacist reporting that his current psychotropic medication regimen was not effective. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, cannabis use, BPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prediabetes, gastroesophageal reflex disease, and a pulmonary nodule. On initial presentation, the patient was prescribed buprenorphine 24 mg/naloxone 6 mg, quetiapine 400 mg, duloxetine 120 mg, and prazosin 15 mg per day. At the time of pharmacy consultation, last reported alcohol or nonprescribed opioid use was about 6 months prior, and methamphetamine use about 1 month prior, with ongoing cannabis use. The patient had a history of participating in cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and residential treatment for both PTSD and substance use. Additionally, he was actively participating in contingency management for stimulant use disorder and self-management and recovery training group.

The patient reported ongoing mood lability, hypervigilance, and oversedation with current psychotropic regimen. The prescriber of his medication for opioid use disorder also reported the patient experienced labile mood, impulsive behavior, and anger outbursts. In the setting of intolerability due to oversedation with quetiapine, cardiometabolic risk, and lack of clear indication for use, the patient and health care practitioner (HCP) agreed to taper quetiapine and initiate a trial of DVP for affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol. To prevent cholinergic rebound and insomnia with abrupt discontinuation of quetiapine, DVP and quetiapine were cross tapered. The following cross taper was prescribed: quetiapine 300 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 1; quetiapine 200 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 2; quetiapine 100 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 3; quetiapine 50 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 4; followed by DVP 1000 mg per day and discontinuation of quetiapine.

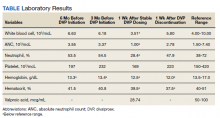

During a 4-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported appropriate completion of cross taper but stopped taking the DVP 3 days prior to the appointment due to self-reported lack of efficacy. For this reason, serum VPA level was not obtained. After discussion with his HCP, the patient restarted DVP 1000 mg per day without retitration with plans to get laboratory tests in 1 week. The next week, laboratory tests were notable for VPA level 28.74 (reference range, 50-100) µg/mL, low WBC 3.51 (reference range, 4.00-10.00) 103/mcL, platelets 169 (reference range, 150-420) 103/mcL, and low ANC 1.00 (reference range, 1.50-7.40) 103/mcL (Table). This raised clinical concern as the patient had no history of documented neutropenia or leukopenia, with most recent complete blood count (CBC) prior to DVP initiation 3 months earlier while prescribed quetiapine.

On further review, the HCP opted to cease administration of DVP and repeat CBC with differential in 1 week. Nine days later, laboratory tests were performed and compared with those collected the week before, revealing resolution of neutropenia and leukopenia. A score of 7 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (NADRPS) was determined based on previous conclusive reports on the reaction (+1), appeared after suspected drug administration (+2), improved with drug discontinuation (+1), confirmed by objective evidence (+1), and no alternative causes could be found (+2).29 With a NADRPS score of 7, an AE of probable DVP-induced neutropenia was documented and medication was not resumed.

Discussion

Our case report describes isolated neutropenia and leukopenia that developed after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP. Hematologic abnormalities resolved after discontinuation of DVP, suggesting a likely correlation. DVP has a well-established, dose-related prevalence of thrombocytopenia occurring in up to 27% of patients.1 Fewer case reports exist on neutropenia and leukopenia. DVP-induced neutropenia is thought to be a result of direct bone marrow suppression, whereas the more commonly occurring blood dyscrasia, thrombocytopenia, is thought to be caused by an antibody-mediated destruction of platelets.6

Management of DVP-induced thrombocytopenia is often dependent on the severity of the reaction. In mild-to-moderate cases, intervention may not be necessary as thrombocytopenia has been shown to resolve without adjustment to DVP therapy.1 In more severe or symptomatic cases, dose reduction or discontinuation of the offending agent is recommended, typically resulting in resolution shortly following pharmacologic intervention.

Guidance on the management of other drug-induced hematologic abnormalities, such as neutropenia and leukopenia are not as well established. A 2019 systematic review of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia suggested that continuing the offending drug with strict monitoring could be considered in cases of mild neutropenia. In cases of moderate neutropenia, the author suggests temporary cessation of the drug and reinstatement once neutrophil count normalizes and definitive cessation of the drug in severe cases.30

In our case, continuing the offending agent with close monitoring was considered, similar to the well-established management of clozapine-induced neutropenia. However, due to the concern that the ANC was bordering moderate neutropenia in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level as well as a significant reduction in platelets, although not meeting criteria for thrombocytopenia, the decision was made to err on the side of caution and discontinue the most likely offending agent.

It is important to highlight that DVP was replacing quetiapine in the form of a cross taper. Quetiapine is structurally similar to clozapine. While clozapine has strict monitoring requirements related to neutropenia, blood dyscrasias with quetiapine therapy are rare. Quetiapine-induced hematologic abnormalities may be due to direct toxicity or to an immune-mediated mechanism, leading to bone marrow suppression.20 Case reports documenting blood dyscrasias with the combination of DVP and quetiapine were identified during literature review.15-19 Despite these case reports, we believe DVP was the primary offending agent in our case as the patient’s last dose of quetiapine was 2 weeks before obtaining the abnormal CBC. There was no history of blood dyscrasias with quetiapine monotherapy; however, the effect of the combination of DVP and quetiapine is unknown as no CBC was obtained during the cross-taper period.

Although there are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have some research to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 In our case, DVP was selected due to the evidence for use in BPD and ability to assess adherence with therapeutic monitoring. Although polypharmacy is a concern in patients with BPD, in our case we believed that the patient’s ongoing mood lability and impulsive behaviors warranted pharmacologic intervention. Additionally, DVP provided an advantage in its ability to quickly titrate to therapeutic dose when compared with lamotrigine and a lower risk of cognitive AEs when compared with topiramate.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this case report demonstrates the first published case of neutropenia and leukopenia related to DVP therapy for the treatment of BPD. Routine CBC monitoring is recommended with DVP therapy, and our case highlights the importance of evaluating for not only thrombocytopenia, but also other blood dyscrasias during the titration phase even in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level. Further studies are warranted to determine incidence of DVP-related neutropenia and leukopenia and to evaluate the safety of continuing DVP in cases of mild-to-moderate neutropenia with close monitoring.

Valproic acid (VPA) and its derivative, divalproex (DVP) are prescribed for a variety of indications, commonly for seizure control in patients with epilepsy, mood stabilization in patients with bipolar disorder, and migraine prophylaxis. Gastrointestinal distress and sedation are among the most reported adverse effects (AEs) with DVP therapy.1 Although serious hepatic and hematologic AEs are rare, monitoring is still recommended. DVP can cause various hematologic dyscrasias, the most common being thrombocytopenia.1,2 Neutropenia and leukopenia have been reported in isolated cases, most occurring in pediatric patients or patients with epilepsy.3-14

Several case reports of DVP-related neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] < 1.50 103/mcL) and leukopenia (white blood cell count [WBC] < 4.0 103/mcL) were reviewed during our literature search, some caused by DVP monotherapy; others were thought to be related to concomitant use of DVP and another drug.15-25 Quetiapine was the antipsychotic most commonly implicated in causing hematologic abnormalities when combined with DVP. We report a case of neutropenia and leukopenia that presented after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP for the treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Although no medications have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have literature to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 A therapeutic range for DVP in the treatment of BPD has not been defined; therefore, for this case report, the generally accepted range of 50 to 100 µg/mL will be considered therapeutic.1

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old male patient presented to the mental health clinic pharmacist reporting that his current psychotropic medication regimen was not effective. His medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, stimulant use disorder, cannabis use, BPD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, prediabetes, gastroesophageal reflex disease, and a pulmonary nodule. On initial presentation, the patient was prescribed buprenorphine 24 mg/naloxone 6 mg, quetiapine 400 mg, duloxetine 120 mg, and prazosin 15 mg per day. At the time of pharmacy consultation, last reported alcohol or nonprescribed opioid use was about 6 months prior, and methamphetamine use about 1 month prior, with ongoing cannabis use. The patient had a history of participating in cognitive processing therapy, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and residential treatment for both PTSD and substance use. Additionally, he was actively participating in contingency management for stimulant use disorder and self-management and recovery training group.

The patient reported ongoing mood lability, hypervigilance, and oversedation with current psychotropic regimen. The prescriber of his medication for opioid use disorder also reported the patient experienced labile mood, impulsive behavior, and anger outbursts. In the setting of intolerability due to oversedation with quetiapine, cardiometabolic risk, and lack of clear indication for use, the patient and health care practitioner (HCP) agreed to taper quetiapine and initiate a trial of DVP for affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol. To prevent cholinergic rebound and insomnia with abrupt discontinuation of quetiapine, DVP and quetiapine were cross tapered. The following cross taper was prescribed: quetiapine 300 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 1; quetiapine 200 mg and DVP 500 mg per day for week 2; quetiapine 100 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 3; quetiapine 50 mg and DVP 1000 mg per day for week 4; followed by DVP 1000 mg per day and discontinuation of quetiapine.

During a 4-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported appropriate completion of cross taper but stopped taking the DVP 3 days prior to the appointment due to self-reported lack of efficacy. For this reason, serum VPA level was not obtained. After discussion with his HCP, the patient restarted DVP 1000 mg per day without retitration with plans to get laboratory tests in 1 week. The next week, laboratory tests were notable for VPA level 28.74 (reference range, 50-100) µg/mL, low WBC 3.51 (reference range, 4.00-10.00) 103/mcL, platelets 169 (reference range, 150-420) 103/mcL, and low ANC 1.00 (reference range, 1.50-7.40) 103/mcL (Table). This raised clinical concern as the patient had no history of documented neutropenia or leukopenia, with most recent complete blood count (CBC) prior to DVP initiation 3 months earlier while prescribed quetiapine.

On further review, the HCP opted to cease administration of DVP and repeat CBC with differential in 1 week. Nine days later, laboratory tests were performed and compared with those collected the week before, revealing resolution of neutropenia and leukopenia. A score of 7 on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (NADRPS) was determined based on previous conclusive reports on the reaction (+1), appeared after suspected drug administration (+2), improved with drug discontinuation (+1), confirmed by objective evidence (+1), and no alternative causes could be found (+2).29 With a NADRPS score of 7, an AE of probable DVP-induced neutropenia was documented and medication was not resumed.

Discussion

Our case report describes isolated neutropenia and leukopenia that developed after a cross taper from quetiapine to DVP. Hematologic abnormalities resolved after discontinuation of DVP, suggesting a likely correlation. DVP has a well-established, dose-related prevalence of thrombocytopenia occurring in up to 27% of patients.1 Fewer case reports exist on neutropenia and leukopenia. DVP-induced neutropenia is thought to be a result of direct bone marrow suppression, whereas the more commonly occurring blood dyscrasia, thrombocytopenia, is thought to be caused by an antibody-mediated destruction of platelets.6

Management of DVP-induced thrombocytopenia is often dependent on the severity of the reaction. In mild-to-moderate cases, intervention may not be necessary as thrombocytopenia has been shown to resolve without adjustment to DVP therapy.1 In more severe or symptomatic cases, dose reduction or discontinuation of the offending agent is recommended, typically resulting in resolution shortly following pharmacologic intervention.

Guidance on the management of other drug-induced hematologic abnormalities, such as neutropenia and leukopenia are not as well established. A 2019 systematic review of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia suggested that continuing the offending drug with strict monitoring could be considered in cases of mild neutropenia. In cases of moderate neutropenia, the author suggests temporary cessation of the drug and reinstatement once neutrophil count normalizes and definitive cessation of the drug in severe cases.30

In our case, continuing the offending agent with close monitoring was considered, similar to the well-established management of clozapine-induced neutropenia. However, due to the concern that the ANC was bordering moderate neutropenia in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level as well as a significant reduction in platelets, although not meeting criteria for thrombocytopenia, the decision was made to err on the side of caution and discontinue the most likely offending agent.

It is important to highlight that DVP was replacing quetiapine in the form of a cross taper. Quetiapine is structurally similar to clozapine. While clozapine has strict monitoring requirements related to neutropenia, blood dyscrasias with quetiapine therapy are rare. Quetiapine-induced hematologic abnormalities may be due to direct toxicity or to an immune-mediated mechanism, leading to bone marrow suppression.20 Case reports documenting blood dyscrasias with the combination of DVP and quetiapine were identified during literature review.15-19 Despite these case reports, we believe DVP was the primary offending agent in our case as the patient’s last dose of quetiapine was 2 weeks before obtaining the abnormal CBC. There was no history of blood dyscrasias with quetiapine monotherapy; however, the effect of the combination of DVP and quetiapine is unknown as no CBC was obtained during the cross-taper period.

Although there are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of BPD, mood stabilizers, including DVP, have some research to support their use for the treatment of affective dysregulation and impulsive-behavioral dyscontrol.26-28 In our case, DVP was selected due to the evidence for use in BPD and ability to assess adherence with therapeutic monitoring. Although polypharmacy is a concern in patients with BPD, in our case we believed that the patient’s ongoing mood lability and impulsive behaviors warranted pharmacologic intervention. Additionally, DVP provided an advantage in its ability to quickly titrate to therapeutic dose when compared with lamotrigine and a lower risk of cognitive AEs when compared with topiramate.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this case report demonstrates the first published case of neutropenia and leukopenia related to DVP therapy for the treatment of BPD. Routine CBC monitoring is recommended with DVP therapy, and our case highlights the importance of evaluating for not only thrombocytopenia, but also other blood dyscrasias during the titration phase even in the absence of a therapeutic VPA level. Further studies are warranted to determine incidence of DVP-related neutropenia and leukopenia and to evaluate the safety of continuing DVP in cases of mild-to-moderate neutropenia with close monitoring.

1. Depakote (valproic acid). Package insert. Abbott Laboratories; June 2000.

2. Conley EL, Coley KC, Pollock BG, Dapos SV, Maxwell R, Branch RA. Prevalence and risk of thrombocytopenia with valproic acid: experience at a psychiatric teaching hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1325-1330. doi:10.1592/phco.21.17.1325.34418

3. Jaeken J, van Goethem C, Casaer P, Devlieger H, Eggermont E, Pilet M. Neutropenia during sodium valproate therapy. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54(12):986-987. doi:10.1136/adc.54.12.986

4. Barr RD, Copeland SA, Stockwell MC, Morris N, Kelton JC. Valproic acid and immune thrombocytopenia. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(9):681-684. doi:10.1136/adc.57.9.681

5. Symon DNK, Russell G. Sodium valproate and neutropenia (letter). Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:235. doi:10.1136/adc.58.3.235

6. Watts RG, Emanuel PD, Zuckerman KS, Howard TH. Valproic acid-induced cytopenias: evidence for a dose-related suppression of hematopoiesis. J Pediatr. 1990;117(3):495-499. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81105-9

7. Blackburn SC, Oliart AD, García-Rodríguez LA, Pérez Gutthann S. Antiepileptics and blood dyscrasias: a cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18(6):1277-1283.

8. Acharya S, Bussel JB. Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(1):62-65. doi:10.1097/00043426-200001000-00012

9. Vesta KS, Medina PJ. Valproic acid-induced neutropenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(6):819-821. doi:10.1345/aph.1C381

10. Kohli U, Gulati, S. Sodium valproate induced isolated neutropenia. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(9):844-844. doi:10.1007/BF02790401

11. Hsu HC, Tseng HK, Wang SC, Wang YY. Valproic acid-induced agranulocytosis. Int J Gerontol. 2009;3(2):137-139. doi:10.1016/S1873-9598(09)70036-5

12. Chakraborty S, Chakraborty J, Mandal S, Ghosal MK. A rare occurrence of isolated neutropenia with valproic acid: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109(5):345-346.

13. Stoner SC, Deal E, Lurk JT. Delayed-onset neutropenia with divalproex sodium. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(10):1507-1510. doi:10.1345/aph.1L239

14. Storch DD. Severe leukopenia with valproate. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1208-1209. doi:10.1097/00004583-200010000-00003

15. Rahman A, Mican LM, Fischer C, Campbell AH. Evaluating the incidence of leukopenia and neutropenia with valproate, quetiapine, or the combination in children and adolescents. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:822-830. doi:10.1345/aph.1L617

16. Hung WC, Hsieh MH. Neutropenia associated with the comedication of quetiapine and valproate in 2 elderly patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):416-417. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182549d2d

17. Park HJ, Kim JY. Incidence of neutropenia with valproate and quetiapine combination treatment in subjects with acquired brain injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(2):183-188. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.09.004

18. Estabrook KR, Pheister M. A case of quetiapine XR and divalproex-associated neutropenia followed by successful use of ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):417-418. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318253a071

19. Nair P, Lippmann S. Is leukopenia associated with divalproex and/or quetiapine? Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):188-189. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.188

20. Cowan C, Oakley C. Leukopenia and neutropenia induced by quetiapine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):292-294. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.07.003

21. Fan KY, Chen WY, Huang MC. Quetiapine-associated leucopenia and thrombocytopenia: a case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:110. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0495-9

22. Malik S, Lally J, Ajnakina O, et al. Sodium valproate and clozapine induced neutropenia: A case control study using register data. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:267-273. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.041

23. Pantelis C, Adesanya A. Increased risk of neutropaenia and agranulocytosis with sodium valproate used adjunctively with clozapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(4):544-545. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.0911f.x

24. Madeb R, Hirschmann S, Kurs R, Turkie A, Modai I. Combined clozapine and valproic acid treatment-induced agranulocytosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):238-239. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00659-4

25. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, Theison M, Emrich HM. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31(4):122-125. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979312

26. Ingenhoven T, Lafay P, Rinne T, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden H. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for severe personality disorders: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:14. doi:10.4088/jcp.08r04526gre

27. Mercer D, Douglass AB, Links PS. Meta-analyses of mood stabilizers, antidepressants and antipsychotics in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: effectiveness for depression and anger symptoms. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(2):156-174. doi:10.1521/pedi.2009.23.2.156

28. Hollander E, Swann AC, Coccaro EF, Jiang P, Smith TB. Impact of trait impulsivity and state aggression on divalproex versus placebo response in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):621-624. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.621

29. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.154

30. Andrès E, Villalba NL, Zulfiqar AA, Serraj K, Mourot-Cottet R, Gottenberg AJ. State of art of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia or agranulocytosis, with a focus on biotherapies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1351. doi:10.3390/jcm8091351

1. Depakote (valproic acid). Package insert. Abbott Laboratories; June 2000.

2. Conley EL, Coley KC, Pollock BG, Dapos SV, Maxwell R, Branch RA. Prevalence and risk of thrombocytopenia with valproic acid: experience at a psychiatric teaching hospital. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(11):1325-1330. doi:10.1592/phco.21.17.1325.34418

3. Jaeken J, van Goethem C, Casaer P, Devlieger H, Eggermont E, Pilet M. Neutropenia during sodium valproate therapy. Arch Dis Child. 1979;54(12):986-987. doi:10.1136/adc.54.12.986

4. Barr RD, Copeland SA, Stockwell MC, Morris N, Kelton JC. Valproic acid and immune thrombocytopenia. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57(9):681-684. doi:10.1136/adc.57.9.681

5. Symon DNK, Russell G. Sodium valproate and neutropenia (letter). Arch Dis Child. 1983;58:235. doi:10.1136/adc.58.3.235

6. Watts RG, Emanuel PD, Zuckerman KS, Howard TH. Valproic acid-induced cytopenias: evidence for a dose-related suppression of hematopoiesis. J Pediatr. 1990;117(3):495-499. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81105-9

7. Blackburn SC, Oliart AD, García-Rodríguez LA, Pérez Gutthann S. Antiepileptics and blood dyscrasias: a cohort study. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18(6):1277-1283.

8. Acharya S, Bussel JB. Hematologic toxicity of sodium valproate. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(1):62-65. doi:10.1097/00043426-200001000-00012

9. Vesta KS, Medina PJ. Valproic acid-induced neutropenia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(6):819-821. doi:10.1345/aph.1C381

10. Kohli U, Gulati, S. Sodium valproate induced isolated neutropenia. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(9):844-844. doi:10.1007/BF02790401

11. Hsu HC, Tseng HK, Wang SC, Wang YY. Valproic acid-induced agranulocytosis. Int J Gerontol. 2009;3(2):137-139. doi:10.1016/S1873-9598(09)70036-5

12. Chakraborty S, Chakraborty J, Mandal S, Ghosal MK. A rare occurrence of isolated neutropenia with valproic acid: a case report. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109(5):345-346.

13. Stoner SC, Deal E, Lurk JT. Delayed-onset neutropenia with divalproex sodium. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(10):1507-1510. doi:10.1345/aph.1L239

14. Storch DD. Severe leukopenia with valproate. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1208-1209. doi:10.1097/00004583-200010000-00003

15. Rahman A, Mican LM, Fischer C, Campbell AH. Evaluating the incidence of leukopenia and neutropenia with valproate, quetiapine, or the combination in children and adolescents. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:822-830. doi:10.1345/aph.1L617

16. Hung WC, Hsieh MH. Neutropenia associated with the comedication of quetiapine and valproate in 2 elderly patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):416-417. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182549d2d

17. Park HJ, Kim JY. Incidence of neutropenia with valproate and quetiapine combination treatment in subjects with acquired brain injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(2):183-188. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.09.004

18. Estabrook KR, Pheister M. A case of quetiapine XR and divalproex-associated neutropenia followed by successful use of ziprasidone. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):417-418. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318253a071

19. Nair P, Lippmann S. Is leukopenia associated with divalproex and/or quetiapine? Psychosomatics. 2005;46(2):188-189. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.188

20. Cowan C, Oakley C. Leukopenia and neutropenia induced by quetiapine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(1):292-294. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.07.003

21. Fan KY, Chen WY, Huang MC. Quetiapine-associated leucopenia and thrombocytopenia: a case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:110. doi:10.1186/s12888-015-0495-9

22. Malik S, Lally J, Ajnakina O, et al. Sodium valproate and clozapine induced neutropenia: A case control study using register data. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:267-273. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.041

23. Pantelis C, Adesanya A. Increased risk of neutropaenia and agranulocytosis with sodium valproate used adjunctively with clozapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(4):544-545. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.0911f.x

24. Madeb R, Hirschmann S, Kurs R, Turkie A, Modai I. Combined clozapine and valproic acid treatment-induced agranulocytosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17(4):238-239. doi:10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00659-4

25. Dose M, Hellweg R, Yassouridis A, Theison M, Emrich HM. Combined treatment of schizophrenic psychoses with haloperidol and valproate. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998;31(4):122-125. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979312

26. Ingenhoven T, Lafay P, Rinne T, Passchier J, Duivenvoorden H. Effectiveness of pharmacotherapy for severe personality disorders: meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:14. doi:10.4088/jcp.08r04526gre

27. Mercer D, Douglass AB, Links PS. Meta-analyses of mood stabilizers, antidepressants and antipsychotics in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: effectiveness for depression and anger symptoms. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(2):156-174. doi:10.1521/pedi.2009.23.2.156

28. Hollander E, Swann AC, Coccaro EF, Jiang P, Smith TB. Impact of trait impulsivity and state aggression on divalproex versus placebo response in borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):621-624. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.621

29. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.154

30. Andrès E, Villalba NL, Zulfiqar AA, Serraj K, Mourot-Cottet R, Gottenberg AJ. State of art of idiosyncratic drug-induced neutropenia or agranulocytosis, with a focus on biotherapies. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1351. doi:10.3390/jcm8091351

Some leukemias detectable up to 16 years before diagnosis?

Previous analyses showed that monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), a CLL precursor state, has been detected up to 6 years before CLL diagnosis, the investigators explained, noting that “[a]nother prognostically relevant immunogenetic feature of CLL concerns the stereotype of the B-cell receptor immunoglobulins (BcR IG).”

“Indeed, distinct stereotyped subsets can be defined by the expression of shared sequence motifs and are associated with particular presentation and outcomes,” P. Martijn Kolijn, PhD, a researcher in the department of immunology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in a brief report published online in Blood. In an effort to “gain insight into the composition of the BcR IG repertoire during the early stages of CLL,” the investigators utilized next-generation sequencing to analyze 124 blood samples taken from healthy individuals up to 22 years before they received a diagnosis of CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL). An additional 118 matched control samples were also analyzed.

Study subjects were participants in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort.

“First, unsurprisingly, we observed a significant difference in the frequency of the dominant clonotype in CLL patients versus controls with a median frequency of 54.9%, compared to only 0.38% in controls,” they wrote.

Among 28 patients whose lymphocyte counts were measured at baseline, 10 showed evidence of lymphocytosis up to 8 years before CLL diagnosis.

This suggests undiagnosed instances of high-count MBL (cases with a cell count above 0.5x 109 cells/L, which can progress to CLL) or asymptomatic CLL, they explained.

“In contrast, next-generation sequencing results showed detectable skewing of the IGH gene repertoire in 21/28 patients up to 15 years before CLL diagnosis, often in the absence of elevated lymphocyte counts,” they wrote. “Remarkably, some patients with CLL requiring treatment and clinical transformation to an aggressive B-cell lymphoma displayed considerable skewing in the IGH gene repertoire even 16 years before CLL diagnosis.”

Patients with a prediagnostic IGHV-unmutated dominant clonotype had significantly shorter overall survival after CLL diagnosis than did those with an IGHV-mutated clonotype, they noted.

“Furthermore, at early timepoints (>10 years before diagnosis), patients with a high dominant clonotype frequency were more likely to be IGHV mutated, whereas closer to diagnosis this tendency was lost, indicating that the prediagnostic phase may be even longer than 16 years for [mutated] CLL patients,” they added.

The investigators also found that:

- Twenty-five patients carried stereotyped BcR IG up to 17 years prior to CLL diagnosis, and of these, 10 clonotypes were assigned to minor subsets and 15 to major CLL subsets. Among the latter, 14 of the 15 belonged to high-risk subsets, and most of those showed a trend for faster disease evolution.

- High frequency of the dominant clonotype was evident in samples obtained less than 6 years before diagnosis, whereas high-risk stereotyped clonotypes found longer before diagnosis (as early as 16 years) tended to have a lower dominant clonotype frequency (<20% of IGH gene repertoire)

- The stereotyped BcR IG matched the clonotype at diagnosis for both patients with diagnostic material.

- No stereotyped subsets were identified among the dominant clonotypes of the healthy controls.

“To our knowledge, the dynamics of the emergence of biclonality in an MBL patient and subsequent progression to CLL have never been captured in such a convincing manner,” they noted.

The findings “extend current knowledge on the evolution of the IGH repertoire prior to CLL diagnosis, highlighting that even high-risk CLL subtypes may display a prolonged indolent preclinical stage,” they added, speculating that “somatic genetic aberrations, (auto)stimulation, epigenetic and/or microenvironmental influences are required for the transformation into overt CLL.”

The investigators also noted that since the observed skewing in the IGH gene repertoire often occurs prior to B-cell lymphocytosis, they consider the findings “a novel extension to the characterization of MBL.”

“Further studies may prove invaluable in the clinical distinction between ‘progressing’ MBL versus ‘stable’ MBL. Notwithstanding the above, we emphasize that early detection is only warranted if it provides clear benefits to patient care,” they concluded.

In a related commentary, Gerald Marti, MD, PhD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, emphasized that the findings “represent the earliest detection of a clonotypic precursor cell for CLL.” .

They also raise new questions and point to new directions for research, Dr. Marti noted.

“Where do we go from here? CLL has a long evolutionary history in which early branching may start as an oligoclonal process (antigen stimulation) and include driver mutations,” he wrote. “A long-term analysis of the B-cell repertoire in familial CLL might shed light on this process. Further clarification of the mechanisms of age-related immune senescence is also of interest.”

The study authors and Dr. Marti reported having no competing financial interests.

Previous analyses showed that monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), a CLL precursor state, has been detected up to 6 years before CLL diagnosis, the investigators explained, noting that “[a]nother prognostically relevant immunogenetic feature of CLL concerns the stereotype of the B-cell receptor immunoglobulins (BcR IG).”

“Indeed, distinct stereotyped subsets can be defined by the expression of shared sequence motifs and are associated with particular presentation and outcomes,” P. Martijn Kolijn, PhD, a researcher in the department of immunology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in a brief report published online in Blood. In an effort to “gain insight into the composition of the BcR IG repertoire during the early stages of CLL,” the investigators utilized next-generation sequencing to analyze 124 blood samples taken from healthy individuals up to 22 years before they received a diagnosis of CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL). An additional 118 matched control samples were also analyzed.

Study subjects were participants in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort.

“First, unsurprisingly, we observed a significant difference in the frequency of the dominant clonotype in CLL patients versus controls with a median frequency of 54.9%, compared to only 0.38% in controls,” they wrote.

Among 28 patients whose lymphocyte counts were measured at baseline, 10 showed evidence of lymphocytosis up to 8 years before CLL diagnosis.

This suggests undiagnosed instances of high-count MBL (cases with a cell count above 0.5x 109 cells/L, which can progress to CLL) or asymptomatic CLL, they explained.

“In contrast, next-generation sequencing results showed detectable skewing of the IGH gene repertoire in 21/28 patients up to 15 years before CLL diagnosis, often in the absence of elevated lymphocyte counts,” they wrote. “Remarkably, some patients with CLL requiring treatment and clinical transformation to an aggressive B-cell lymphoma displayed considerable skewing in the IGH gene repertoire even 16 years before CLL diagnosis.”

Patients with a prediagnostic IGHV-unmutated dominant clonotype had significantly shorter overall survival after CLL diagnosis than did those with an IGHV-mutated clonotype, they noted.

“Furthermore, at early timepoints (>10 years before diagnosis), patients with a high dominant clonotype frequency were more likely to be IGHV mutated, whereas closer to diagnosis this tendency was lost, indicating that the prediagnostic phase may be even longer than 16 years for [mutated] CLL patients,” they added.

The investigators also found that:

- Twenty-five patients carried stereotyped BcR IG up to 17 years prior to CLL diagnosis, and of these, 10 clonotypes were assigned to minor subsets and 15 to major CLL subsets. Among the latter, 14 of the 15 belonged to high-risk subsets, and most of those showed a trend for faster disease evolution.

- High frequency of the dominant clonotype was evident in samples obtained less than 6 years before diagnosis, whereas high-risk stereotyped clonotypes found longer before diagnosis (as early as 16 years) tended to have a lower dominant clonotype frequency (<20% of IGH gene repertoire)

- The stereotyped BcR IG matched the clonotype at diagnosis for both patients with diagnostic material.

- No stereotyped subsets were identified among the dominant clonotypes of the healthy controls.

“To our knowledge, the dynamics of the emergence of biclonality in an MBL patient and subsequent progression to CLL have never been captured in such a convincing manner,” they noted.

The findings “extend current knowledge on the evolution of the IGH repertoire prior to CLL diagnosis, highlighting that even high-risk CLL subtypes may display a prolonged indolent preclinical stage,” they added, speculating that “somatic genetic aberrations, (auto)stimulation, epigenetic and/or microenvironmental influences are required for the transformation into overt CLL.”

The investigators also noted that since the observed skewing in the IGH gene repertoire often occurs prior to B-cell lymphocytosis, they consider the findings “a novel extension to the characterization of MBL.”

“Further studies may prove invaluable in the clinical distinction between ‘progressing’ MBL versus ‘stable’ MBL. Notwithstanding the above, we emphasize that early detection is only warranted if it provides clear benefits to patient care,” they concluded.

In a related commentary, Gerald Marti, MD, PhD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, emphasized that the findings “represent the earliest detection of a clonotypic precursor cell for CLL.” .

They also raise new questions and point to new directions for research, Dr. Marti noted.

“Where do we go from here? CLL has a long evolutionary history in which early branching may start as an oligoclonal process (antigen stimulation) and include driver mutations,” he wrote. “A long-term analysis of the B-cell repertoire in familial CLL might shed light on this process. Further clarification of the mechanisms of age-related immune senescence is also of interest.”

The study authors and Dr. Marti reported having no competing financial interests.

Previous analyses showed that monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), a CLL precursor state, has been detected up to 6 years before CLL diagnosis, the investigators explained, noting that “[a]nother prognostically relevant immunogenetic feature of CLL concerns the stereotype of the B-cell receptor immunoglobulins (BcR IG).”

“Indeed, distinct stereotyped subsets can be defined by the expression of shared sequence motifs and are associated with particular presentation and outcomes,” P. Martijn Kolijn, PhD, a researcher in the department of immunology at Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues wrote in a brief report published online in Blood. In an effort to “gain insight into the composition of the BcR IG repertoire during the early stages of CLL,” the investigators utilized next-generation sequencing to analyze 124 blood samples taken from healthy individuals up to 22 years before they received a diagnosis of CLL or small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL). An additional 118 matched control samples were also analyzed.

Study subjects were participants in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort.

“First, unsurprisingly, we observed a significant difference in the frequency of the dominant clonotype in CLL patients versus controls with a median frequency of 54.9%, compared to only 0.38% in controls,” they wrote.

Among 28 patients whose lymphocyte counts were measured at baseline, 10 showed evidence of lymphocytosis up to 8 years before CLL diagnosis.

This suggests undiagnosed instances of high-count MBL (cases with a cell count above 0.5x 109 cells/L, which can progress to CLL) or asymptomatic CLL, they explained.

“In contrast, next-generation sequencing results showed detectable skewing of the IGH gene repertoire in 21/28 patients up to 15 years before CLL diagnosis, often in the absence of elevated lymphocyte counts,” they wrote. “Remarkably, some patients with CLL requiring treatment and clinical transformation to an aggressive B-cell lymphoma displayed considerable skewing in the IGH gene repertoire even 16 years before CLL diagnosis.”

Patients with a prediagnostic IGHV-unmutated dominant clonotype had significantly shorter overall survival after CLL diagnosis than did those with an IGHV-mutated clonotype, they noted.

“Furthermore, at early timepoints (>10 years before diagnosis), patients with a high dominant clonotype frequency were more likely to be IGHV mutated, whereas closer to diagnosis this tendency was lost, indicating that the prediagnostic phase may be even longer than 16 years for [mutated] CLL patients,” they added.

The investigators also found that:

- Twenty-five patients carried stereotyped BcR IG up to 17 years prior to CLL diagnosis, and of these, 10 clonotypes were assigned to minor subsets and 15 to major CLL subsets. Among the latter, 14 of the 15 belonged to high-risk subsets, and most of those showed a trend for faster disease evolution.

- High frequency of the dominant clonotype was evident in samples obtained less than 6 years before diagnosis, whereas high-risk stereotyped clonotypes found longer before diagnosis (as early as 16 years) tended to have a lower dominant clonotype frequency (<20% of IGH gene repertoire)

- The stereotyped BcR IG matched the clonotype at diagnosis for both patients with diagnostic material.

- No stereotyped subsets were identified among the dominant clonotypes of the healthy controls.

“To our knowledge, the dynamics of the emergence of biclonality in an MBL patient and subsequent progression to CLL have never been captured in such a convincing manner,” they noted.

The findings “extend current knowledge on the evolution of the IGH repertoire prior to CLL diagnosis, highlighting that even high-risk CLL subtypes may display a prolonged indolent preclinical stage,” they added, speculating that “somatic genetic aberrations, (auto)stimulation, epigenetic and/or microenvironmental influences are required for the transformation into overt CLL.”

The investigators also noted that since the observed skewing in the IGH gene repertoire often occurs prior to B-cell lymphocytosis, they consider the findings “a novel extension to the characterization of MBL.”

“Further studies may prove invaluable in the clinical distinction between ‘progressing’ MBL versus ‘stable’ MBL. Notwithstanding the above, we emphasize that early detection is only warranted if it provides clear benefits to patient care,” they concluded.

In a related commentary, Gerald Marti, MD, PhD, of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, emphasized that the findings “represent the earliest detection of a clonotypic precursor cell for CLL.” .

They also raise new questions and point to new directions for research, Dr. Marti noted.

“Where do we go from here? CLL has a long evolutionary history in which early branching may start as an oligoclonal process (antigen stimulation) and include driver mutations,” he wrote. “A long-term analysis of the B-cell repertoire in familial CLL might shed light on this process. Further clarification of the mechanisms of age-related immune senescence is also of interest.”

The study authors and Dr. Marti reported having no competing financial interests.

FROM BLOOD

Cancer Data Trends 2022

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Federal Practitioner, in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), present the 2022 edition of Cancer Data Trends (click to view the digital edition). This special issue provides updates on some of the top cancers and related concerns affecting veterans through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Exposure-Related Cancers

- Cancer in Women

- Genitourinary Cancers

- Gastrointestinal Cancers

- Telehealth in Oncology

- Precision Oncology

- Palliative and Hospice Care

- Alcohol and Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Oropharyngeal Cancer

- Hematologic Cancers

Federal Practitioner and AVAHO would like to thank the following experts for their contributions to this issue:

Anita Aggarwal, DO, PhD; Sara Ahmed, PhD; Katherine Faricy-Anderson, MD; Apar Kishor Ganti, MD, MS; Solomon A Graf, MD; Kate Hendricks Thomas, PhD; Michael Kelley, MD; Mark Klein, MD, Gina McWhirter, MSN, MBA, RN; Bruce Montgomery, MD; Vida Almario Passero, MD, MBA; Thomas D Rodgers, MD; Vlad C Sandulache, MD, PhD; David H Wang, MD, PhD.

Hematocrit, White Blood Cells, and Thrombotic Events in the Veteran Population With Polycythemia Vera