User login

Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: Understanding Its Many Forms

- Raghu G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

- Cottin V et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:799912. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.799912

- Molina-Molina M et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(7):765-774. doi:10.1080/17476348.2022.2107508

- Cottin V. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(1):11-13. doi:10.1164/rccm.202208-1639ED

- Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):958-968. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2005230

- Chiu YH et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106560. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106560

- Wong AW et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):148. doi:10.1186/s12890-022-01922-2

- Raghu G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

- Cottin V et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:799912. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.799912

- Molina-Molina M et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(7):765-774. doi:10.1080/17476348.2022.2107508

- Cottin V. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(1):11-13. doi:10.1164/rccm.202208-1639ED

- Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):958-968. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2005230

- Chiu YH et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106560. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106560

- Wong AW et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):148. doi:10.1186/s12890-022-01922-2

- Raghu G et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(9):e18-e47. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

- Cottin V et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:799912. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.799912

- Molina-Molina M et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2022;16(7):765-774. doi:10.1080/17476348.2022.2107508

- Cottin V. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(1):11-13. doi:10.1164/rccm.202208-1639ED

- Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(10):958-968. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2005230

- Chiu YH et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1106560. doi:10.3389/fmed.2023.1106560

- Wong AW et al. BMC Pulm Med. 2022;22(1):148. doi:10.1186/s12890-022-01922-2

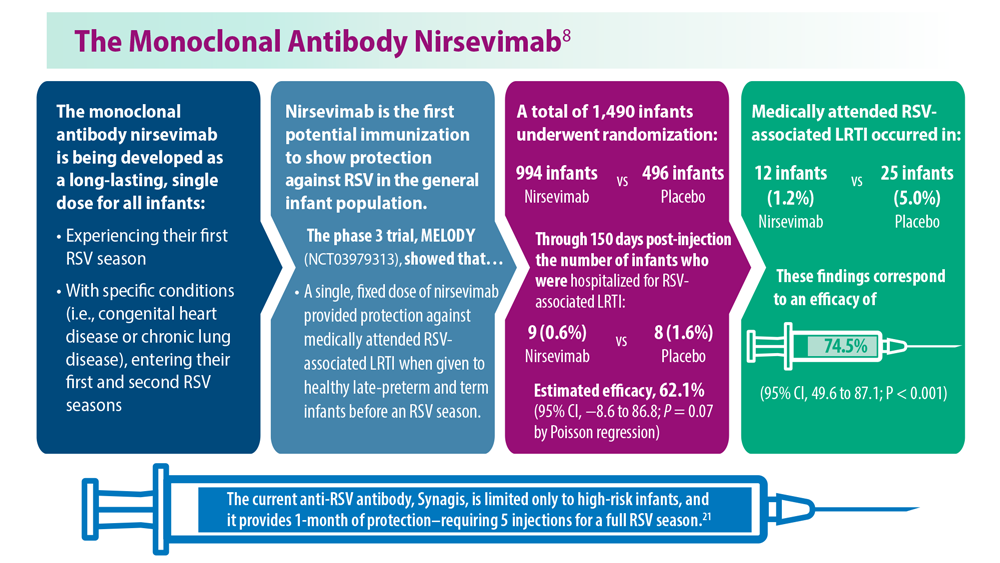

Long-Awaited RSV Vaccines Now Available for Older Adults and Pediatric Patients

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

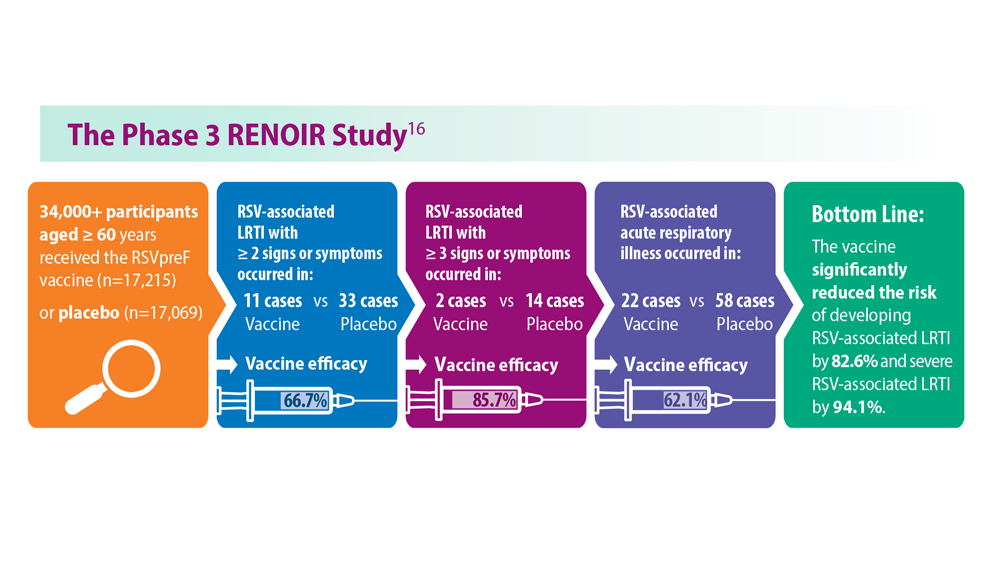

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

- Jha A et al. Respiratory syncytial virus. In: Hui DS, Rossi GA, Johnston SL, eds. Respiratory Syncytial Virus. SARS, MERS and Other Viral Lung Infections. European Respiratory Society; 2016:chap 5. Accessed May 17, 2023.

- Ginsburg SA, Srikantiah P. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(12):e1644-e6145. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00455-1

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [press release]. Published May 3, 2023. Accessed May 17, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-respiratory-syncytial-virus-rsv-vaccine

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves New Drug to Prevent RSV in Babies and Toddlers [press release]. Published July 17, 2023. Accessed August 11, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-prevent-rsv-babies-and-toddlers

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Vaccine for Pregnant Individuals to Prevent RSV in Infants. Published August 21, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-vaccine-pregnant-individuals-prevent-rsv-infants

- Madhi SA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(5):426-439. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa1908380

- Centers for Disease Control. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Meeting recommendations, August 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/recommendations.html

- Hammit LL et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(9):837-846. doi:10.1056/ NEJMoa2110275

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in infants and young children. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/ high-risk/infants-young-children.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. RSV in older adults and adults with chronic medical conditions. Updated October 28, 2022. Accessed May 30, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/rsv/high-risk/older-adults.html

- Widmer K et al. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(1):56-62. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis309

- Hall CB et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):588-598. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804877

- McLaughlin JM et al. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac300. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofac300

- Thompson et al. JAMA. 2003;289(2):179-186. doi:10.1001/jama.289.2.179

- Hansen CL et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220527. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0527

- Walsh EE et al; RENOIR Clinical Trial Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1465-1477. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213836

- Martin JA et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(13):1-47. PMID:32501202

- Townsi N et al. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5(1):1487214. doi:10.1080/20018525.20 18.1487214

- Malek A et al. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1994;32(1):8-14. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.1994.tb00873.x

- Kampmann B et al; MATISSE Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1451- 1464. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2216480

- Synagis (palivizumab) injection prescribing information. Published June 2023. Accessed August 2023. https://www.synagis.com/synagis.pdf

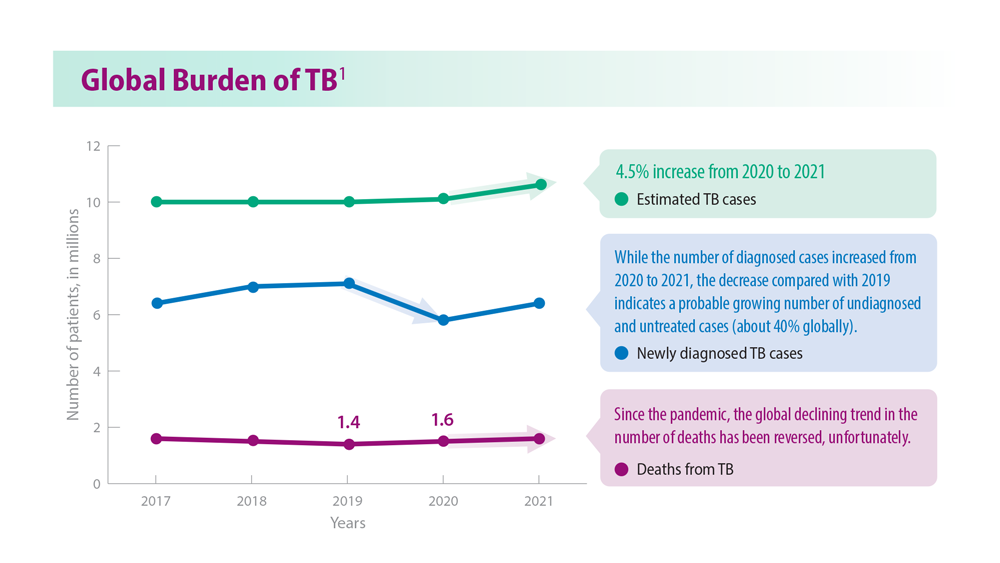

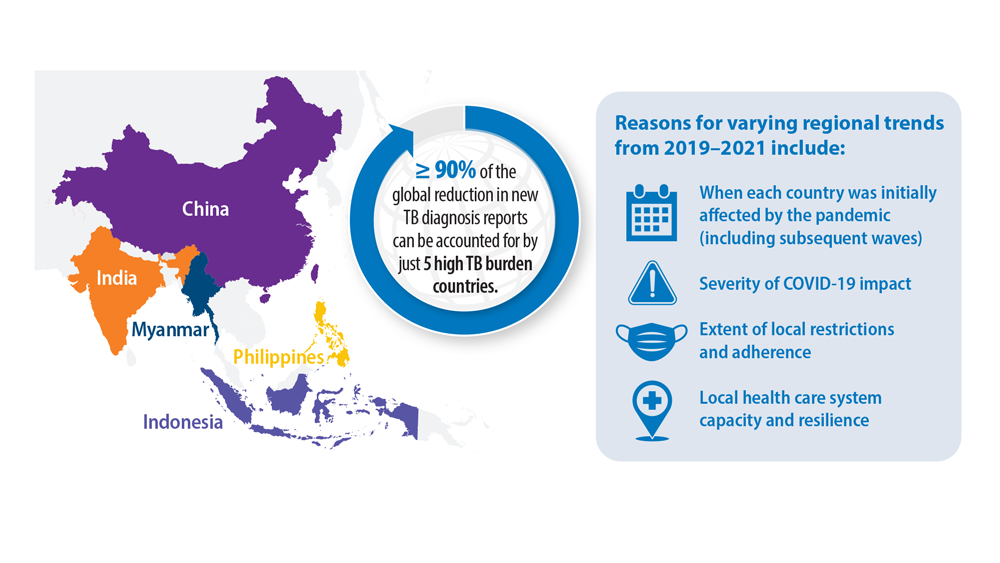

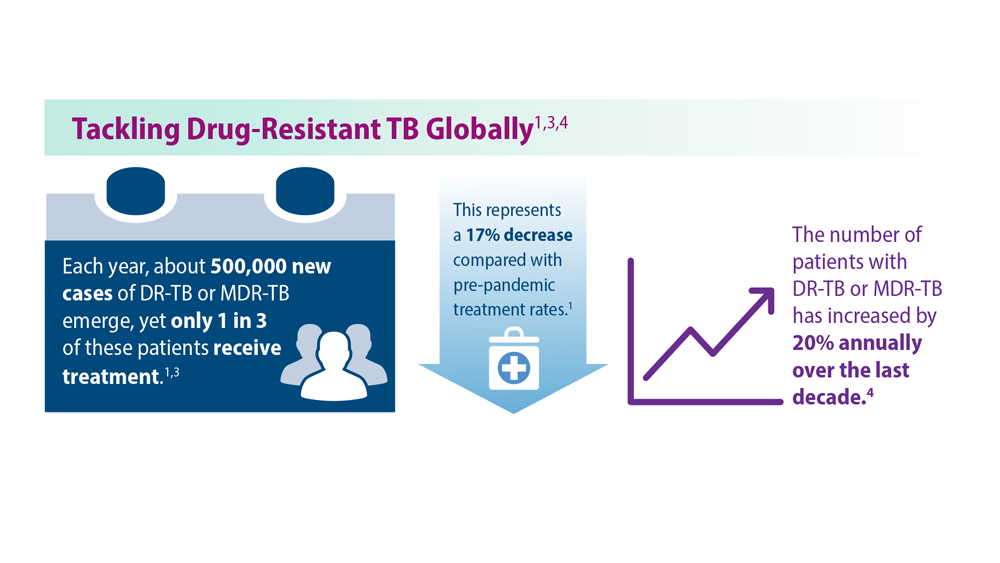

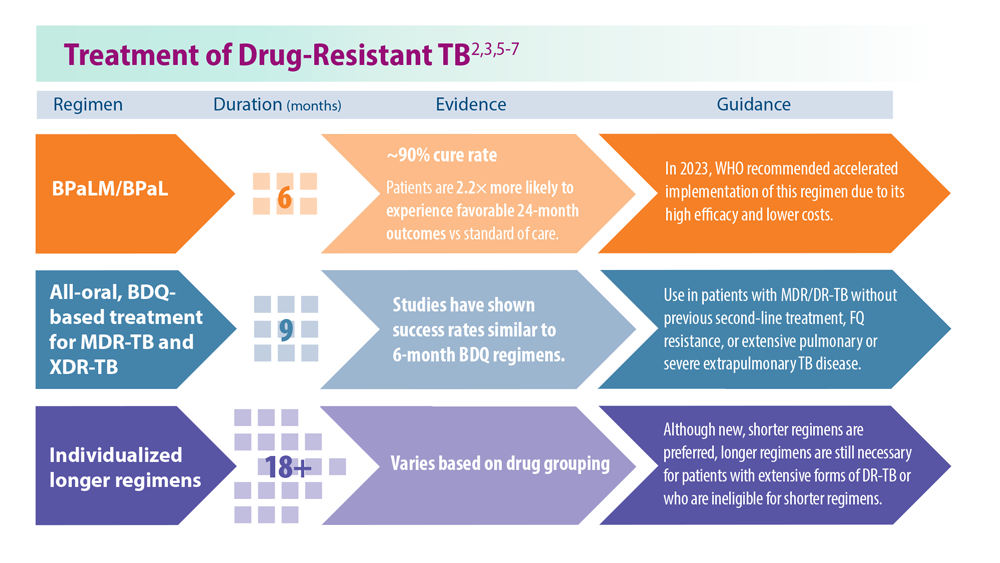

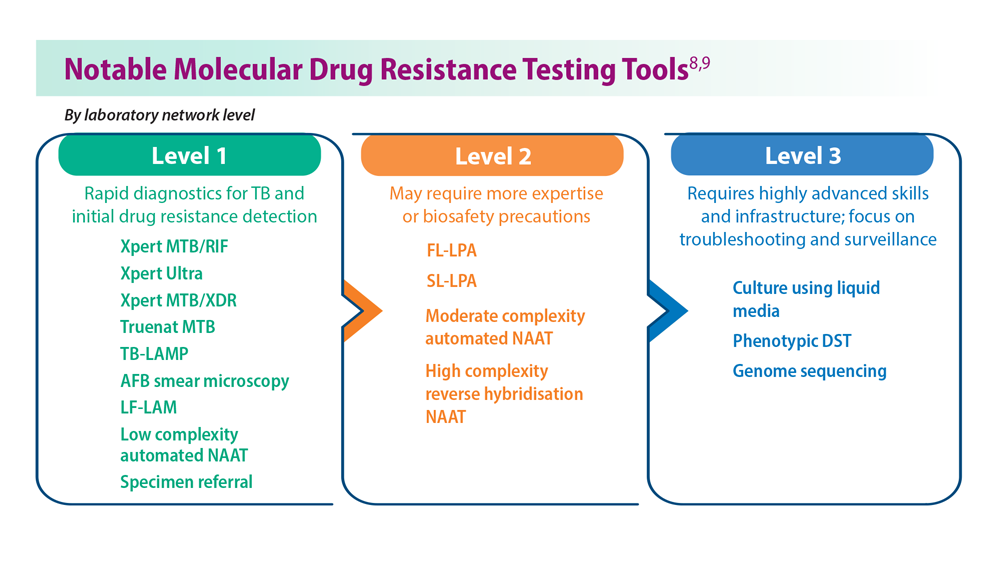

Tuberculosis Management: Returning to Pre-Pandemic Priorities

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

- Global tuberculosis report 2022. World Health Organization. Published October 27, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061729

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment, 2022 update. World Health Organization. Published December 15, 2022. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240063129

- Migliori GB, Tiberi S. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2022 ;26(7):590-591. doi:10.5588/ijtld.22.0263.

- Lange C et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1142-1144. doi:10.1164/rccm.202202-0393ED

- Esmail A et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(10):1214-1227. doi:10.1164/rccm.202107-1779OC

- WHO BPaLM Accelerator Platform: to support the call to action for implementation of the shorter and more effective treatment for all people suffering from drug-resistant TB. World Health Organization. Published May 9, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/detail/2023/05/09/default-calendar/who-bpalm-accelerator-platform–to-support-the-call-to-action-for-implementation-of-the-shorter-and-moreeffective-

- Trevisi L et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;207(11):1525-1532. doi:10.1164/rccm.202211-2125OC

- Domínguez J et al; TBnet and RESIST-TB networks. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23(4):e122-e137. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00875-1

- WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 3: diagnosis: rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. World Health Organization. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030589treatment-for-all-people-suffering-from-drug-resistant-tb

Severity score predicts mortality in pulmonary tuberculosis

, based on data from approximately 400 individuals.

Although a mortality risk-prediction score could improve treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis patients, such a score has not been previously reported, wrote Takeshi Osawa, MD, of Fukujuji Hospital, Tokyo, and colleagues.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers used 252 patients from a previous perspective study of newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis as the development cohort, and recruited 165 additional patients between March 2021 and September 2022.

The primary endpoint was all-cause in-hospital mortality. Based on data from the development group, the researchers found that age 65 years and older and age 80 years and older, hypoxemia, activities of daily living, bilateral pulmonary lesions, lymphocyte count of less than 720 microliters, serum albumin less than 2.86 mg/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 3.97 mg/dL or higher, and procalcitonin (PCT) 0.130 ng/mL or higher were predictors of all-cause in hospital mortality.

The researchers used this information to create the disease severity score, known as the AHL score. The AHL included three clinical parameters: activity in daily living (semi-dependent, 1 point; totally dependent, 2 points); hypoxemia (1 point) and lymphocytes (< 720 /mcL, 1 point).

The scoring systems for the three parameters were, respectively, 1 point for semi-dependent and 2 points totally dependent (for activity in daily living), 1 point for presence of hypoxemia, and 1 point for lymphocytes less than 720 per microliter. The researchers stratified the scores into levels of low, intermediate, and high risk, with scores of 0, 1-2, and 3-4, respectively.

All-cause in hospital mortality occurred in 39 (15.5%) and 17 (10.3%) of patients in the developmental and validation cohorts, respectively.

The AHL score effectively predicted mortality, dividing patients into three groups of 1.3% low-risk, 8.9% intermediate risk, and 39.3% high-risk in the validation cohort, with a Harrell’s c-statistic of 0.842.

The corresponding numbers for the development cohort were 0, 13.5%, and 55.8%, with a c-statistic of 0.902.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data from “smear-negative” patients who were treated as outpatients, and more research is needed to determine the applicability of the AHL score in an outpatient population, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on long-term mortality in surviving patients who were discharged, and the reliance on assessments that can be performed only in clinical settings in developed countries, they said.

However, the results support the feasibility of the AHL score in clinical settings to accurately predict mortality in patients with pulmonary TB, and may help optimize treatments for this population, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. All authors disclosed nonfinancial support in the form of measuring reagents from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation during the study but had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from approximately 400 individuals.

Although a mortality risk-prediction score could improve treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis patients, such a score has not been previously reported, wrote Takeshi Osawa, MD, of Fukujuji Hospital, Tokyo, and colleagues.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers used 252 patients from a previous perspective study of newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis as the development cohort, and recruited 165 additional patients between March 2021 and September 2022.

The primary endpoint was all-cause in-hospital mortality. Based on data from the development group, the researchers found that age 65 years and older and age 80 years and older, hypoxemia, activities of daily living, bilateral pulmonary lesions, lymphocyte count of less than 720 microliters, serum albumin less than 2.86 mg/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 3.97 mg/dL or higher, and procalcitonin (PCT) 0.130 ng/mL or higher were predictors of all-cause in hospital mortality.

The researchers used this information to create the disease severity score, known as the AHL score. The AHL included three clinical parameters: activity in daily living (semi-dependent, 1 point; totally dependent, 2 points); hypoxemia (1 point) and lymphocytes (< 720 /mcL, 1 point).

The scoring systems for the three parameters were, respectively, 1 point for semi-dependent and 2 points totally dependent (for activity in daily living), 1 point for presence of hypoxemia, and 1 point for lymphocytes less than 720 per microliter. The researchers stratified the scores into levels of low, intermediate, and high risk, with scores of 0, 1-2, and 3-4, respectively.

All-cause in hospital mortality occurred in 39 (15.5%) and 17 (10.3%) of patients in the developmental and validation cohorts, respectively.

The AHL score effectively predicted mortality, dividing patients into three groups of 1.3% low-risk, 8.9% intermediate risk, and 39.3% high-risk in the validation cohort, with a Harrell’s c-statistic of 0.842.

The corresponding numbers for the development cohort were 0, 13.5%, and 55.8%, with a c-statistic of 0.902.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data from “smear-negative” patients who were treated as outpatients, and more research is needed to determine the applicability of the AHL score in an outpatient population, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on long-term mortality in surviving patients who were discharged, and the reliance on assessments that can be performed only in clinical settings in developed countries, they said.

However, the results support the feasibility of the AHL score in clinical settings to accurately predict mortality in patients with pulmonary TB, and may help optimize treatments for this population, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. All authors disclosed nonfinancial support in the form of measuring reagents from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation during the study but had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

, based on data from approximately 400 individuals.

Although a mortality risk-prediction score could improve treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis patients, such a score has not been previously reported, wrote Takeshi Osawa, MD, of Fukujuji Hospital, Tokyo, and colleagues.

In a study published in the journal CHEST, the researchers used 252 patients from a previous perspective study of newly diagnosed pulmonary tuberculosis as the development cohort, and recruited 165 additional patients between March 2021 and September 2022.

The primary endpoint was all-cause in-hospital mortality. Based on data from the development group, the researchers found that age 65 years and older and age 80 years and older, hypoxemia, activities of daily living, bilateral pulmonary lesions, lymphocyte count of less than 720 microliters, serum albumin less than 2.86 mg/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP) 3.97 mg/dL or higher, and procalcitonin (PCT) 0.130 ng/mL or higher were predictors of all-cause in hospital mortality.

The researchers used this information to create the disease severity score, known as the AHL score. The AHL included three clinical parameters: activity in daily living (semi-dependent, 1 point; totally dependent, 2 points); hypoxemia (1 point) and lymphocytes (< 720 /mcL, 1 point).

The scoring systems for the three parameters were, respectively, 1 point for semi-dependent and 2 points totally dependent (for activity in daily living), 1 point for presence of hypoxemia, and 1 point for lymphocytes less than 720 per microliter. The researchers stratified the scores into levels of low, intermediate, and high risk, with scores of 0, 1-2, and 3-4, respectively.

All-cause in hospital mortality occurred in 39 (15.5%) and 17 (10.3%) of patients in the developmental and validation cohorts, respectively.

The AHL score effectively predicted mortality, dividing patients into three groups of 1.3% low-risk, 8.9% intermediate risk, and 39.3% high-risk in the validation cohort, with a Harrell’s c-statistic of 0.842.

The corresponding numbers for the development cohort were 0, 13.5%, and 55.8%, with a c-statistic of 0.902.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of data from “smear-negative” patients who were treated as outpatients, and more research is needed to determine the applicability of the AHL score in an outpatient population, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the lack of data on long-term mortality in surviving patients who were discharged, and the reliance on assessments that can be performed only in clinical settings in developed countries, they said.

However, the results support the feasibility of the AHL score in clinical settings to accurately predict mortality in patients with pulmonary TB, and may help optimize treatments for this population, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. All authors disclosed nonfinancial support in the form of measuring reagents from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation during the study but had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

Pulmonary aspergillosis predicts poor outcomes in critically ill flu patients

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Critically ill influenza patients with associated pulmonary aspergillosis were more than twice as likely to die in intensive care than those without the added infection, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

Reports of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) are rising in critically ill patients, but data on risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes are limited, Lawrence Y. Lu, MD, of The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues wrote. In addition, diagnosis of IAPA can be challenging, and many clinicians report low awareness of the condition.

In a study published in the journal Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 10 observational studies including 1,720 critically ill influenza patients aged 16 years and older; of these, 331 had IAPA, for a prevalence of 19.2%. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality in the hospital and in the ICU. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and the need for supportive care (invasive and noninvasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, pressor support, and extracorporeal membranous oxygenation).

Overall, mortality among flu patients in the ICU was significantly higher for those with IAPA than those without IAPA (45.0% vs. 23.8%, respectively), as was all-cause mortality (46.4% vs. 26.2%, respectively; odds ratio, 2.6 and P < .001 for both ICU and all-cause mortality).

Factors significantly associated with an increased risk for IAPA included organ transplant (OR, 4.8), hematogenous malignancy (OR, 2.5), being immunocompromised in some way (OR, 2.2), and prolonged corticosteroid use prior to hospital admission (OR, 2.4).

IAPA also was associated with more severe disease, a higher rate of complications, longer ICU stays, and a greater need for organ supports, the researchers noted. Clinical features not significantly more common in patients with IAPA included fever, hemoptysis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

The findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design of the included studies and inability to control for all potential confounders, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the variations in study design, variability of practice patterns across locations, and inclusion of data mainly from countries of high socioeconomic status.

“Given the apparent waning of the COVID-19 pandemic and re-emergence of influenza, our analysis also revealed other gaps in the current literature, including the need to validate newer diagnostic methods and to develop a system to measure severity of IAPA,” the researchers added.

However, the current study results reflect IAPA prevalence from previous studies, and support the need to have a lower threshold for IAPA testing and initiation of antifungal treatment, even with limited data for clinical guidance, they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL CHEST

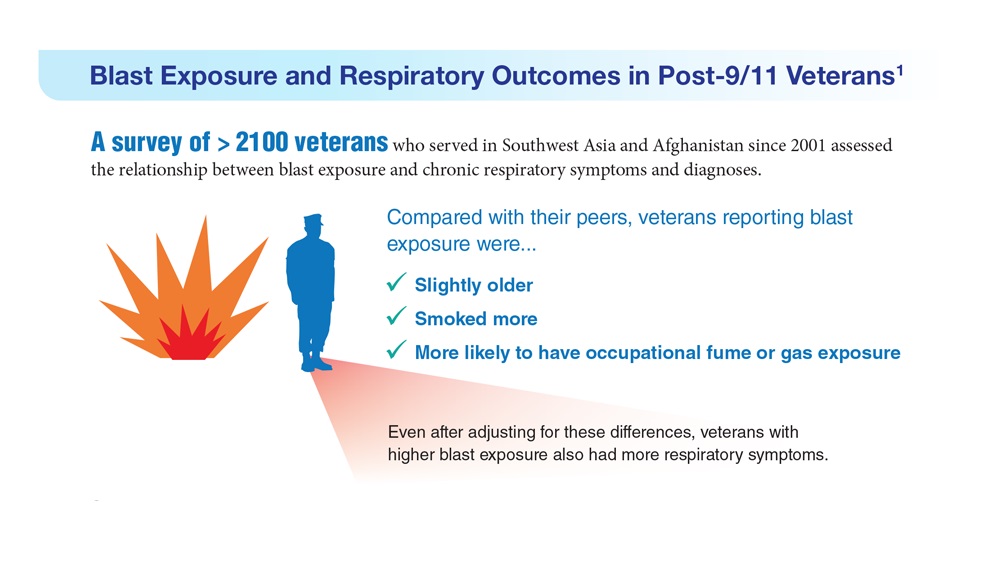

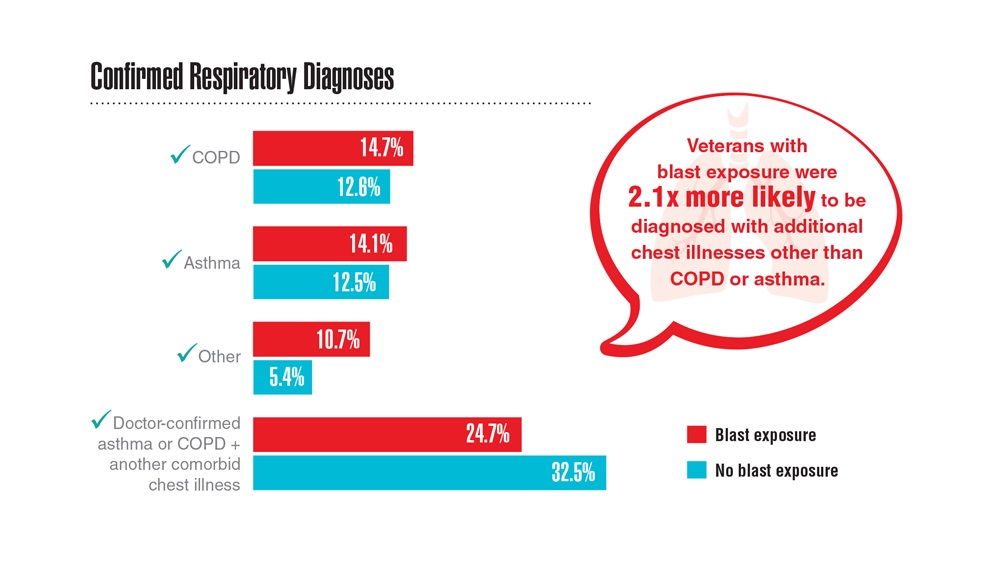

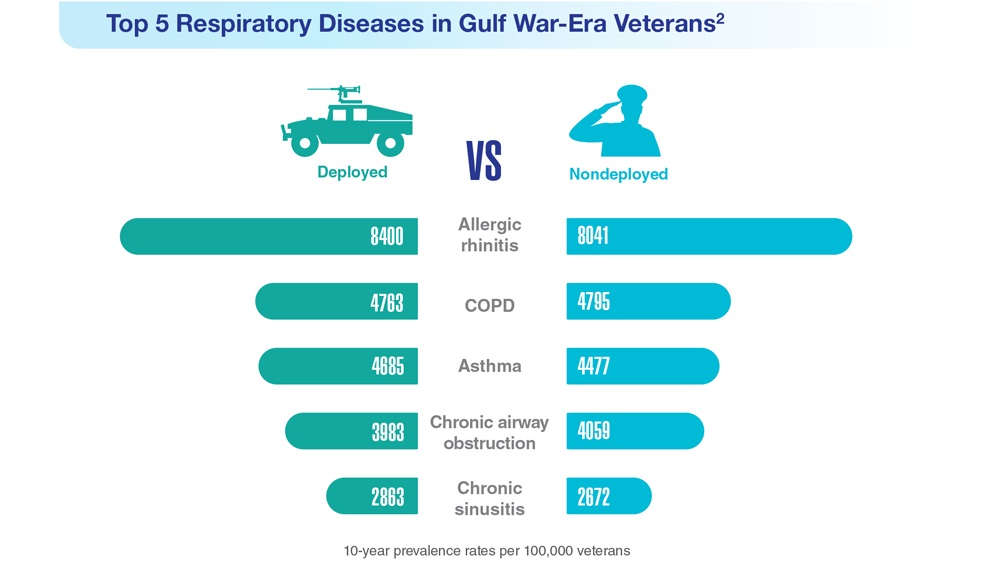

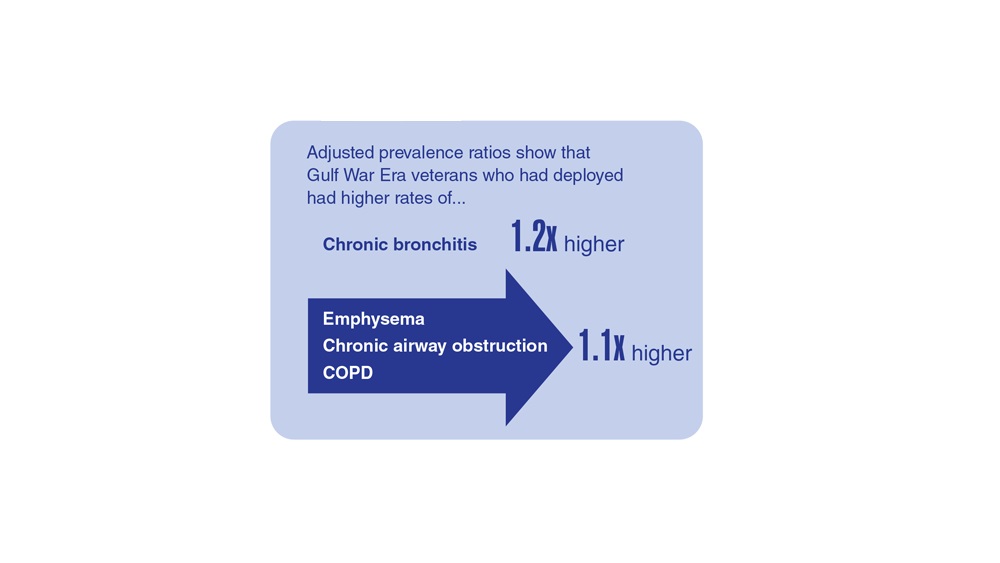

Data Trends 2023: Respiratory Illnesses

- Hines SE et al. Respir Med. 2022;202:106963. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106963

- Dursa EK et al. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63(11):980-987. doi:10.1002/ajim.23172

- Bamonti PM et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Hines SE et al. Respir Med. 2022;202:106963. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106963

- Dursa EK et al. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63(11):980-987. doi:10.1002/ajim.23172

- Bamonti PM et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

- Hines SE et al. Respir Med. 2022;202:106963. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106963

- Dursa EK et al. Am J Ind Med. 2020;63(11):980-987. doi:10.1002/ajim.23172

- Bamonti PM et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

Federal Health Care Data Trends 2023

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Federal Health Care Data Trends (click to view the digital edition) is a special supplement to Federal Practitioner, highlighting the latest research and study outcomes related to the health of veteran and active-duty populations.

In this issue:

- Limb Loss and Prostheses

- Neurology

- Cardiology

- Mental Health

- Diabetes

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Respiratory illnesses

- Women's Health

- HPV and Related Cancers

Three antibiotic regimens show similar effectiveness for CAP

Adults with nonsevere community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) responded nearly equally to three first-line and alternative antibiotic regimens, based on data from more than 23,000 individuals.

Current recommendations for the treatment of CAP vary across guidelines, wrote Anthony D. Bai, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues. However, most guidelines were based on studies that were not powered to examine the effect of treatments on mortality, they said.

“Large observational studies could fill this gap by comparing multiple treatment arms, including patients not well represented in trials, and having a large sample size powered to detect a difference in mortality,” they noted.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 23,512 consecutive patients admitted to 19 hospitals in Canada for CAP between 2015 and 2021. Patients were treated with one of four initial antibiotic regimens: beta-lactam plus macrolide (BL+M), beta-lactam alone (BL), respiratory fluoroquinolone (FQ), or beta-lactam plus doxycycline (BL+D). Of these, BL+M is generally considered the first-line regimen, the researchers noted.

Patients were divided into four groups according to their initial antibiotic treatment within 48 hours of admission; 9,340 patients received BL+M, 9,146 received BL, 4,510 received FQ, and 516 received BL+D. The duration of any antibiotic that was active against CAP was at least 4 days, or until hospital discharge or death.

The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, which was 7.5%, 9.7%, 6.7%, and 6.0% for patients in each of the four treatment groups, respectively. Relative to the first-line therapy of BL+M, the adjusted risk differences for BL, FQ, and BL+D were 1.5%, –0.9%, and –1.9%, respectively.

The adjusted in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between BL+M and either FQ or BL+D, but the difference of 1.5% seen with BL alone suggested a “small but clinically important difference,” the researchers noted.

Key secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay and being discharged alive. The median length of stay was 4.6 days for BL+M, 5.2 days for BL, 4.6 days for FQ, and 6.0 days for BL+D. Patients treated with BL also had a longer time to hospital discharge, which suggests that BL may not be as effective as the other regimens, the researchers said. In addition, patients in the BL group had a subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.90 for being discharged alive, compared with the BL+M group after adjustment with propensity scores and overlap weighting.

Overall, the results support dropping BL as a first-line regimen in the current ATS/IDSA guidelines, and support the recommendation of BL+M, FQ, and BL+D as similarly effective options as listed in other guidelines, applied according to other patient characteristics. For example, “Doxycycline may be preferred over a macrolide in many cases such as macrolide allergy, prolonged QT, or high [Clostridioides] difficile risk,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of follow-up data after hospital discharge.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and use of a comprehensive database that allowed adjustment for many variables, as well as the availability of complete follow-up data for the time spent in the hospital. Based on this study, clinicians may choose a respiratory fluoroquinolone, a beta-lactam plus macrolide, or a beta-lactam plus doxycycline for equally effective antibiotic treatment of CAP, based on the best fit for each individual patient, the researchers concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Adults with nonsevere community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) responded nearly equally to three first-line and alternative antibiotic regimens, based on data from more than 23,000 individuals.

Current recommendations for the treatment of CAP vary across guidelines, wrote Anthony D. Bai, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues. However, most guidelines were based on studies that were not powered to examine the effect of treatments on mortality, they said.

“Large observational studies could fill this gap by comparing multiple treatment arms, including patients not well represented in trials, and having a large sample size powered to detect a difference in mortality,” they noted.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 23,512 consecutive patients admitted to 19 hospitals in Canada for CAP between 2015 and 2021. Patients were treated with one of four initial antibiotic regimens: beta-lactam plus macrolide (BL+M), beta-lactam alone (BL), respiratory fluoroquinolone (FQ), or beta-lactam plus doxycycline (BL+D). Of these, BL+M is generally considered the first-line regimen, the researchers noted.

Patients were divided into four groups according to their initial antibiotic treatment within 48 hours of admission; 9,340 patients received BL+M, 9,146 received BL, 4,510 received FQ, and 516 received BL+D. The duration of any antibiotic that was active against CAP was at least 4 days, or until hospital discharge or death.

The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, which was 7.5%, 9.7%, 6.7%, and 6.0% for patients in each of the four treatment groups, respectively. Relative to the first-line therapy of BL+M, the adjusted risk differences for BL, FQ, and BL+D were 1.5%, –0.9%, and –1.9%, respectively.

The adjusted in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between BL+M and either FQ or BL+D, but the difference of 1.5% seen with BL alone suggested a “small but clinically important difference,” the researchers noted.

Key secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay and being discharged alive. The median length of stay was 4.6 days for BL+M, 5.2 days for BL, 4.6 days for FQ, and 6.0 days for BL+D. Patients treated with BL also had a longer time to hospital discharge, which suggests that BL may not be as effective as the other regimens, the researchers said. In addition, patients in the BL group had a subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.90 for being discharged alive, compared with the BL+M group after adjustment with propensity scores and overlap weighting.

Overall, the results support dropping BL as a first-line regimen in the current ATS/IDSA guidelines, and support the recommendation of BL+M, FQ, and BL+D as similarly effective options as listed in other guidelines, applied according to other patient characteristics. For example, “Doxycycline may be preferred over a macrolide in many cases such as macrolide allergy, prolonged QT, or high [Clostridioides] difficile risk,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of follow-up data after hospital discharge.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and use of a comprehensive database that allowed adjustment for many variables, as well as the availability of complete follow-up data for the time spent in the hospital. Based on this study, clinicians may choose a respiratory fluoroquinolone, a beta-lactam plus macrolide, or a beta-lactam plus doxycycline for equally effective antibiotic treatment of CAP, based on the best fit for each individual patient, the researchers concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Adults with nonsevere community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) responded nearly equally to three first-line and alternative antibiotic regimens, based on data from more than 23,000 individuals.

Current recommendations for the treatment of CAP vary across guidelines, wrote Anthony D. Bai, MD, of Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and colleagues. However, most guidelines were based on studies that were not powered to examine the effect of treatments on mortality, they said.

“Large observational studies could fill this gap by comparing multiple treatment arms, including patients not well represented in trials, and having a large sample size powered to detect a difference in mortality,” they noted.

In a study published in Chest, the researchers reviewed data from 23,512 consecutive patients admitted to 19 hospitals in Canada for CAP between 2015 and 2021. Patients were treated with one of four initial antibiotic regimens: beta-lactam plus macrolide (BL+M), beta-lactam alone (BL), respiratory fluoroquinolone (FQ), or beta-lactam plus doxycycline (BL+D). Of these, BL+M is generally considered the first-line regimen, the researchers noted.

Patients were divided into four groups according to their initial antibiotic treatment within 48 hours of admission; 9,340 patients received BL+M, 9,146 received BL, 4,510 received FQ, and 516 received BL+D. The duration of any antibiotic that was active against CAP was at least 4 days, or until hospital discharge or death.

The primary outcome was all-cause in-hospital mortality, which was 7.5%, 9.7%, 6.7%, and 6.0% for patients in each of the four treatment groups, respectively. Relative to the first-line therapy of BL+M, the adjusted risk differences for BL, FQ, and BL+D were 1.5%, –0.9%, and –1.9%, respectively.

The adjusted in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between BL+M and either FQ or BL+D, but the difference of 1.5% seen with BL alone suggested a “small but clinically important difference,” the researchers noted.

Key secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay and being discharged alive. The median length of stay was 4.6 days for BL+M, 5.2 days for BL, 4.6 days for FQ, and 6.0 days for BL+D. Patients treated with BL also had a longer time to hospital discharge, which suggests that BL may not be as effective as the other regimens, the researchers said. In addition, patients in the BL group had a subdistribution hazard ratio of 0.90 for being discharged alive, compared with the BL+M group after adjustment with propensity scores and overlap weighting.

Overall, the results support dropping BL as a first-line regimen in the current ATS/IDSA guidelines, and support the recommendation of BL+M, FQ, and BL+D as similarly effective options as listed in other guidelines, applied according to other patient characteristics. For example, “Doxycycline may be preferred over a macrolide in many cases such as macrolide allergy, prolonged QT, or high [Clostridioides] difficile risk,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of follow-up data after hospital discharge.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and use of a comprehensive database that allowed adjustment for many variables, as well as the availability of complete follow-up data for the time spent in the hospital. Based on this study, clinicians may choose a respiratory fluoroquinolone, a beta-lactam plus macrolide, or a beta-lactam plus doxycycline for equally effective antibiotic treatment of CAP, based on the best fit for each individual patient, the researchers concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CHEST

Progressive pulmonary fibrosis: treatment and support

MILAN – Numerous unresolved questions surround progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) treatment, according to Elisabeth Bendstrup, MD, PhD, a researcher and clinical professor in the department of clinical medicine – department of respiratory diseases and allergy, Aarhus (Denmark) University, Denmark. These questions regard the optimal timing for treatment initiation, the role of available medications, either as monotherapy or in combination, and nonpharmacologic support options.

What’s in the toolbox?

Pulmonologists who manage PPF have a range of treatment options at their disposal. This includes careful patient observation, with treatment initiation based on clinical necessity. The therapeutic arsenal comprises immunomodulatory treatments, antifibrotic agents, palliative and supportive care, and, for a minority of patients, lung transplantation.

“Once a patient is diagnosed with PPF, it is important to remember that the diagnostic criteria from the guidelines are not exactly the same of those accepted for the reimbursement of antifibrotic treatments in different countries,” Dr. Bendstrup said, suggesting that nonclinical considerations could also potentially influence the treatment choice. She spoke at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Michael Kreuter, MD, director of the Lung Center at the University Hospital in Mainz, Germany, provided insight into the introduction of antifibrotic drugs for the treatment of PPF. Drawing from nearly a decade ago when the first antifibrotic medication was approved for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), Dr. Kreuter noted its effectiveness in slowing disease progression, although it does not reverse it. Subsequently, the discovery that non-IPF diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, exhibited IPF-like behavior led to the exploration of the use of the same drugs for similar conditions, even if not IPF.

“That’s how antifibrotic treatments came into place. Now we have more trials and data to be discussed in the future,” Dr. Kreuter added. He highlighted that antifibrotic drugs are effective for several diseases. Most of those diseases are treated with different anti-inflammatory drugs, which makes it difficult to decide when to start antifibrotic therapy and how to eventually combine it with different pharmacologic approaches.

A pivotal starting point

a question only partially addressed by existing guidelines. Dr. Bendstrup advocated for a comprehensive baseline evaluation. Factors to be considered include symptom burden, the severity of lung decline, radiologic characteristics, signs of alveolar inflammation, progression risk factors, quality of life, patient preferences, and medical history. “All these should be best discussed in a multidisciplinary team, including pulmonologists, nurses, experts in palliative care, occupational physicians, and more,” she said.

Current guidelines recommend nintedanib for PPF treatment for patients who have failed standard management for fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) other than IPF. However, the definition of “standard management” remains a topic of debate, and it is acknowledged that evidence-based guidance for a standard of care varies among patients. Dr. Bendstrup pointed out the limited guidance clinicians receive from these guidelines. “As clinicians, we are not left with very much help from here.”

Choosing the right approach

Dr. Bendstrup delved into the factors influencing the choice between antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory therapies. This decision hinges on whether the patient presents with a predominantly inflammatory or a fibrotic progressive phenotype. Certain clinical characteristics contribute to the decision. Factors such as younger age, female gender, and the presence of connective tissue disease lean toward an inflammatory phenotype. Radiologic patterns, such as organized pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia–like patterns also provide valuable clues. Additionally, genetics plays a role, with shorter telomeres indicating a more fibrotic phenotype and an increased risk of immunomodulatory treatment side effects in non-IPF ILDs.

Bendstrup referred to a recent position paper on treatment recommendations and many other studies that support the use of different treatments for patients with PPF. The authors highlighted limited evidence for immunomodulation in fibrotic ILD, though such treatment is generally used except for ILD associated with systemic sclerosis. Moreover, the guidelines conditionally recommend nintedanib and call for further research on pirfenidone in PPF.

“We need intelligent, well-designed trials looking at subgroups of patients at higher risk, maybe based on molecular identification. We also need to have good biomarkers to better classify our patients based on disease behavior and treatment response. There’s a lot of discussion of biomarkers for progression, much less – if any – on biomarkers for the response to treatment. And we need them as well,” Dr. Bendstrup said in an interview.

The role of supportive care

Effective PPF treatment extends beyond pharmacologic interventions. It encompasses symptom management, patient education on vaccination and smoking cessation, and fostering social support networks. Psychological support, supplemental oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation are integral components of care.

Elisabeth Robertson, a PPF patient representative from the United Kingdom, emphasized the importance of palliative care, not just in end-of-life scenarios but throughout the patient’s journey. Palliative care encompasses symptom alleviation, enabling patients to stay at home when possible, addressing mental health, and preparing for the end of life. Such holistic care can significantly enhance the patient’s quality of life.

The cochair of the session, Marlies S. Wijsenbeek, MD, PhD, pulmonary physician and head of the ILD Centre at the Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, underscored that palliative care begins at diagnosis and involves managing symptom burdens. “Supportive care also includes nurses, as they are precious for the patients while answering their questions and can help save time for the doctors,” she said in an interview.

In the discussion on treatment decisions, experts agreed on the pivotal role of patients in decision-making. However, Dr. Kreuter highlighted two critical factors that influence successful patient-doctor interactions: the cultural backgrounds of patients and their relatives, and the attitudes of health care providers.

Dr. Bendstrup has received honoraria or consultation fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Chiesi, and Daiichi Sankyo. Ms. Robertson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN – Numerous unresolved questions surround progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) treatment, according to Elisabeth Bendstrup, MD, PhD, a researcher and clinical professor in the department of clinical medicine – department of respiratory diseases and allergy, Aarhus (Denmark) University, Denmark. These questions regard the optimal timing for treatment initiation, the role of available medications, either as monotherapy or in combination, and nonpharmacologic support options.

What’s in the toolbox?

Pulmonologists who manage PPF have a range of treatment options at their disposal. This includes careful patient observation, with treatment initiation based on clinical necessity. The therapeutic arsenal comprises immunomodulatory treatments, antifibrotic agents, palliative and supportive care, and, for a minority of patients, lung transplantation.

“Once a patient is diagnosed with PPF, it is important to remember that the diagnostic criteria from the guidelines are not exactly the same of those accepted for the reimbursement of antifibrotic treatments in different countries,” Dr. Bendstrup said, suggesting that nonclinical considerations could also potentially influence the treatment choice. She spoke at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Michael Kreuter, MD, director of the Lung Center at the University Hospital in Mainz, Germany, provided insight into the introduction of antifibrotic drugs for the treatment of PPF. Drawing from nearly a decade ago when the first antifibrotic medication was approved for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), Dr. Kreuter noted its effectiveness in slowing disease progression, although it does not reverse it. Subsequently, the discovery that non-IPF diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, exhibited IPF-like behavior led to the exploration of the use of the same drugs for similar conditions, even if not IPF.

“That’s how antifibrotic treatments came into place. Now we have more trials and data to be discussed in the future,” Dr. Kreuter added. He highlighted that antifibrotic drugs are effective for several diseases. Most of those diseases are treated with different anti-inflammatory drugs, which makes it difficult to decide when to start antifibrotic therapy and how to eventually combine it with different pharmacologic approaches.

A pivotal starting point

a question only partially addressed by existing guidelines. Dr. Bendstrup advocated for a comprehensive baseline evaluation. Factors to be considered include symptom burden, the severity of lung decline, radiologic characteristics, signs of alveolar inflammation, progression risk factors, quality of life, patient preferences, and medical history. “All these should be best discussed in a multidisciplinary team, including pulmonologists, nurses, experts in palliative care, occupational physicians, and more,” she said.

Current guidelines recommend nintedanib for PPF treatment for patients who have failed standard management for fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) other than IPF. However, the definition of “standard management” remains a topic of debate, and it is acknowledged that evidence-based guidance for a standard of care varies among patients. Dr. Bendstrup pointed out the limited guidance clinicians receive from these guidelines. “As clinicians, we are not left with very much help from here.”

Choosing the right approach

Dr. Bendstrup delved into the factors influencing the choice between antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory therapies. This decision hinges on whether the patient presents with a predominantly inflammatory or a fibrotic progressive phenotype. Certain clinical characteristics contribute to the decision. Factors such as younger age, female gender, and the presence of connective tissue disease lean toward an inflammatory phenotype. Radiologic patterns, such as organized pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia–like patterns also provide valuable clues. Additionally, genetics plays a role, with shorter telomeres indicating a more fibrotic phenotype and an increased risk of immunomodulatory treatment side effects in non-IPF ILDs.

Bendstrup referred to a recent position paper on treatment recommendations and many other studies that support the use of different treatments for patients with PPF. The authors highlighted limited evidence for immunomodulation in fibrotic ILD, though such treatment is generally used except for ILD associated with systemic sclerosis. Moreover, the guidelines conditionally recommend nintedanib and call for further research on pirfenidone in PPF.

“We need intelligent, well-designed trials looking at subgroups of patients at higher risk, maybe based on molecular identification. We also need to have good biomarkers to better classify our patients based on disease behavior and treatment response. There’s a lot of discussion of biomarkers for progression, much less – if any – on biomarkers for the response to treatment. And we need them as well,” Dr. Bendstrup said in an interview.

The role of supportive care

Effective PPF treatment extends beyond pharmacologic interventions. It encompasses symptom management, patient education on vaccination and smoking cessation, and fostering social support networks. Psychological support, supplemental oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation are integral components of care.

Elisabeth Robertson, a PPF patient representative from the United Kingdom, emphasized the importance of palliative care, not just in end-of-life scenarios but throughout the patient’s journey. Palliative care encompasses symptom alleviation, enabling patients to stay at home when possible, addressing mental health, and preparing for the end of life. Such holistic care can significantly enhance the patient’s quality of life.

The cochair of the session, Marlies S. Wijsenbeek, MD, PhD, pulmonary physician and head of the ILD Centre at the Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, underscored that palliative care begins at diagnosis and involves managing symptom burdens. “Supportive care also includes nurses, as they are precious for the patients while answering their questions and can help save time for the doctors,” she said in an interview.

In the discussion on treatment decisions, experts agreed on the pivotal role of patients in decision-making. However, Dr. Kreuter highlighted two critical factors that influence successful patient-doctor interactions: the cultural backgrounds of patients and their relatives, and the attitudes of health care providers.

Dr. Bendstrup has received honoraria or consultation fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Chiesi, and Daiichi Sankyo. Ms. Robertson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MILAN – Numerous unresolved questions surround progressive pulmonary fibrosis (PPF) treatment, according to Elisabeth Bendstrup, MD, PhD, a researcher and clinical professor in the department of clinical medicine – department of respiratory diseases and allergy, Aarhus (Denmark) University, Denmark. These questions regard the optimal timing for treatment initiation, the role of available medications, either as monotherapy or in combination, and nonpharmacologic support options.

What’s in the toolbox?

Pulmonologists who manage PPF have a range of treatment options at their disposal. This includes careful patient observation, with treatment initiation based on clinical necessity. The therapeutic arsenal comprises immunomodulatory treatments, antifibrotic agents, palliative and supportive care, and, for a minority of patients, lung transplantation.

“Once a patient is diagnosed with PPF, it is important to remember that the diagnostic criteria from the guidelines are not exactly the same of those accepted for the reimbursement of antifibrotic treatments in different countries,” Dr. Bendstrup said, suggesting that nonclinical considerations could also potentially influence the treatment choice. She spoke at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Michael Kreuter, MD, director of the Lung Center at the University Hospital in Mainz, Germany, provided insight into the introduction of antifibrotic drugs for the treatment of PPF. Drawing from nearly a decade ago when the first antifibrotic medication was approved for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), Dr. Kreuter noted its effectiveness in slowing disease progression, although it does not reverse it. Subsequently, the discovery that non-IPF diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, exhibited IPF-like behavior led to the exploration of the use of the same drugs for similar conditions, even if not IPF.

“That’s how antifibrotic treatments came into place. Now we have more trials and data to be discussed in the future,” Dr. Kreuter added. He highlighted that antifibrotic drugs are effective for several diseases. Most of those diseases are treated with different anti-inflammatory drugs, which makes it difficult to decide when to start antifibrotic therapy and how to eventually combine it with different pharmacologic approaches.

A pivotal starting point

a question only partially addressed by existing guidelines. Dr. Bendstrup advocated for a comprehensive baseline evaluation. Factors to be considered include symptom burden, the severity of lung decline, radiologic characteristics, signs of alveolar inflammation, progression risk factors, quality of life, patient preferences, and medical history. “All these should be best discussed in a multidisciplinary team, including pulmonologists, nurses, experts in palliative care, occupational physicians, and more,” she said.

Current guidelines recommend nintedanib for PPF treatment for patients who have failed standard management for fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) other than IPF. However, the definition of “standard management” remains a topic of debate, and it is acknowledged that evidence-based guidance for a standard of care varies among patients. Dr. Bendstrup pointed out the limited guidance clinicians receive from these guidelines. “As clinicians, we are not left with very much help from here.”

Choosing the right approach

Dr. Bendstrup delved into the factors influencing the choice between antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory therapies. This decision hinges on whether the patient presents with a predominantly inflammatory or a fibrotic progressive phenotype. Certain clinical characteristics contribute to the decision. Factors such as younger age, female gender, and the presence of connective tissue disease lean toward an inflammatory phenotype. Radiologic patterns, such as organized pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonia, or usual interstitial pneumonia–like patterns also provide valuable clues. Additionally, genetics plays a role, with shorter telomeres indicating a more fibrotic phenotype and an increased risk of immunomodulatory treatment side effects in non-IPF ILDs.

Bendstrup referred to a recent position paper on treatment recommendations and many other studies that support the use of different treatments for patients with PPF. The authors highlighted limited evidence for immunomodulation in fibrotic ILD, though such treatment is generally used except for ILD associated with systemic sclerosis. Moreover, the guidelines conditionally recommend nintedanib and call for further research on pirfenidone in PPF.

“We need intelligent, well-designed trials looking at subgroups of patients at higher risk, maybe based on molecular identification. We also need to have good biomarkers to better classify our patients based on disease behavior and treatment response. There’s a lot of discussion of biomarkers for progression, much less – if any – on biomarkers for the response to treatment. And we need them as well,” Dr. Bendstrup said in an interview.

The role of supportive care

Effective PPF treatment extends beyond pharmacologic interventions. It encompasses symptom management, patient education on vaccination and smoking cessation, and fostering social support networks. Psychological support, supplemental oxygen therapy, and pulmonary rehabilitation are integral components of care.

Elisabeth Robertson, a PPF patient representative from the United Kingdom, emphasized the importance of palliative care, not just in end-of-life scenarios but throughout the patient’s journey. Palliative care encompasses symptom alleviation, enabling patients to stay at home when possible, addressing mental health, and preparing for the end of life. Such holistic care can significantly enhance the patient’s quality of life.

The cochair of the session, Marlies S. Wijsenbeek, MD, PhD, pulmonary physician and head of the ILD Centre at the Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, underscored that palliative care begins at diagnosis and involves managing symptom burdens. “Supportive care also includes nurses, as they are precious for the patients while answering their questions and can help save time for the doctors,” she said in an interview.

In the discussion on treatment decisions, experts agreed on the pivotal role of patients in decision-making. However, Dr. Kreuter highlighted two critical factors that influence successful patient-doctor interactions: the cultural backgrounds of patients and their relatives, and the attitudes of health care providers.

Dr. Bendstrup has received honoraria or consultation fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Astra Zeneca, Chiesi, and Daiichi Sankyo. Ms. Robertson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ERS 2023

Paxlovid and Lagevrio benefit COVID outpatients in Omicron era

The American College of Physicians has issued an updated version of its living, rapid practice point guideline on the best treatment options for outpatients with confirmed COVID-19 in the era of the dominant Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. The recommendations in version 2 apply to persons presenting with mild to moderate infection and symptom onset in the past 5 days who are at high risk for progression to severe disease and potential hospitalization or death.

Version 1 appeared in late 2022.

While outpatient management is appropriate for most patients, treatment should be personalized and based on careful risk stratification and informed decision-making, said the guideline authors, led by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA, vice president of clinical policy and the Center for Evidence Reviews at the ACP in Philadelphia.

Practice points

- Consider the oral antivirals nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid) or molnupiravir (Lagevrio) for symptomatic outpatients with confirmed mild to moderate COVID-19 who are within 5 days of the onset of symptoms and at high risk for progressing to severe disease.

New evidence for the Omicron variant suggests a possible net benefit of the antiviral molnupiravir versus standard or no treatment in terms of reducing recovery time if treatment is initiated within 5 days of symptom onset. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir was associated with reductions in COVID-19 hospitalization and all-cause mortality.

“The practice points only address [whether] treatments work compared to placebo, no treatment, or usual care,” cautioned Linda L. Humphrey, MD, MPH, MACP, chair of the ACP’s Population Health and Medical Science Committee and a professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University VA Portland Health Care System. The ACP continues to monitor the evidence. “Once enough evidence has emerged, it will be possible to compare treatments to each other. Until that time we are unable to determine if there is an advantage to using one treatment over another.”

- Do not use the antiparasitic ivermectin (Stromectol) or the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab (Xevudy) to treat this patient population. “It is not expected to be effective against the Omicron variant,” Dr. Humphrey said.

There was no evidence to support the use of medications such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, antihistamines, SSRIs, and multiple other agents.

“The guideline is not a departure from previous knowledge and reflects what appears in other guidelines and is already being done generally in practice,” said Mirella Salvatore, MD, an associate professor of medicine and population health sciences at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was not involved in the ACP statement. It is therefore unlikely the recommendations will trigger controversy or negative feedback, added Dr. Salvatore, who is also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “We believe that our evidence-based approach, which considers the balance of benefits and harms of various treatments, will be embraced by the physician community,” Dr. Humphrey said.

The updated recommendations are based on new data from the evidence review of multiple treatments, which concluded that both nirmatrelvir-ritonavir and molnupiravir likely improve outcomes for outpatients with mild to moderate COVID-19. The review was conducted after the emergence of the Omicron variant by the ACP Center for Evidence Reviews at Cochrane Austria/University for Continuing Education Krems (Austria).

Review details

Inclusion criteria were modified to focus on the Omicron variant by limiting eligible studies to only those enrolling patients on or after Nov. 26, 2021. The investigators included two randomized controlled trials and six retrospective cohort studies and ranked quality of evidence for the effectiveness of the following treatments, compared with usual care or no treatment: azithromycin, camostat mesylate, chloroquine-hydroxychloroquine, chlorpheniramine, colchicine, convalescent plasma, corticosteroids, ensitrelvir, favipiravir, fluvoxamine, ivermectin, lopinavir-ritonavir, molnupiravir, neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, metformin, niclosamide, nitazoxanide, nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, and remdesivir.

It compared results for all-cause and COVID-specific mortality, recovery, time to recovery, COVID hospitalization, and adverse and serious adverse events.

Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir was associated with a reduction in hospitalization caused by COVID-19 of 0.7% versus 1.2% (moderate certainty of evidence [COE]) and a reduction in all-cause mortality of less than 0.1% versus 0.2% (moderate COE).

Molnupiravir led to a higher recovery rate of 31.8% versus 22.6% (moderate COE) and a reduced time to recovery of 9 versus 15 median days (moderate COE). It had no effect, however, on all-cause mortality: 0.02% versus 0.04% (moderate COE). Nor did it affect the incidence of serious adverse events: 0.4% versus 0.3% (moderate COE).

“There have been no head-to-head comparative studies of these two treatments, but nirmatrelvir-ritonavir appears to be the preferred treatment,” Dr. Salvatore said. She noted that molnupiravir cannot be used in pregnant women or young persons under age 18, while nirmatrelvir-ritonavir carries the risk of drug interactions. Viral rebound and recurrence of symptoms have been reported in some patients receiving nirmatrelvir-ritonavir.

In other review findings, ivermectin had no effect on time to recovery (moderate COE) and adverse events versus placebo (low COE). Sotrovimab resulted in no difference in all-cause mortality, compared with no treatment (low COE). There were no eligible studies for all of the other treatments of interest nor were there any that specifically evaluated the benefits and harms of treatments for the Omicron variant.

The panel pointed to the need for more evaluation of the efficacy, effectiveness, and comparative effectiveness, as well as harms of pharmacologic and biologic treatments of COVID-19 in the outpatient setting, particularly in the context of changing dominant SARS-CoV-2 variants and subvariants.

Another area requiring further research is the effectiveness of retreatment in patients with previous COVID-19 infection. Subgroup analyses are also needed to assess whether the efficacy and effectiveness of outpatient treatments vary by age, sex, socioeconomic status, and comorbid conditions – or by SARS-CoV-2 variant, immunity status (prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination status, or time since infection or vaccination), symptom duration, or disease severity.

Dr. Salvatore agreed that more research is needed in special convalescent groups. “For instance, those with cancer who are immunocompromised may need longer treatment and adjunctive treatment with convalescent plasma. But is difficult to find a large enough study with 5,000 immunocompromised patients.”

Financial support for the development of the practice points came exclusively from the ACP operating budget. The evidence review was funded by the ACP. The authors disclosed no relevant high-level competing interests with regard to this guidance, although several authors reported intellectual interests in various areas of research. Dr. Salvatore disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to her comments but is engaged in influenza research for Genentech.

The American College of Physicians has issued an updated version of its living, rapid practice point guideline on the best treatment options for outpatients with confirmed COVID-19 in the era of the dominant Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. The recommendations in version 2 apply to persons presenting with mild to moderate infection and symptom onset in the past 5 days who are at high risk for progression to severe disease and potential hospitalization or death.

Version 1 appeared in late 2022.

While outpatient management is appropriate for most patients, treatment should be personalized and based on careful risk stratification and informed decision-making, said the guideline authors, led by Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA, vice president of clinical policy and the Center for Evidence Reviews at the ACP in Philadelphia.

Practice points

- Consider the oral antivirals nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid) or molnupiravir (Lagevrio) for symptomatic outpatients with confirmed mild to moderate COVID-19 who are within 5 days of the onset of symptoms and at high risk for progressing to severe disease.

New evidence for the Omicron variant suggests a possible net benefit of the antiviral molnupiravir versus standard or no treatment in terms of reducing recovery time if treatment is initiated within 5 days of symptom onset. Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir was associated with reductions in COVID-19 hospitalization and all-cause mortality.

“The practice points only address [whether] treatments work compared to placebo, no treatment, or usual care,” cautioned Linda L. Humphrey, MD, MPH, MACP, chair of the ACP’s Population Health and Medical Science Committee and a professor of medicine at Oregon Health and Science University VA Portland Health Care System. The ACP continues to monitor the evidence. “Once enough evidence has emerged, it will be possible to compare treatments to each other. Until that time we are unable to determine if there is an advantage to using one treatment over another.”

- Do not use the antiparasitic ivermectin (Stromectol) or the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab (Xevudy) to treat this patient population. “It is not expected to be effective against the Omicron variant,” Dr. Humphrey said.

There was no evidence to support the use of medications such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, antihistamines, SSRIs, and multiple other agents.