User login

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

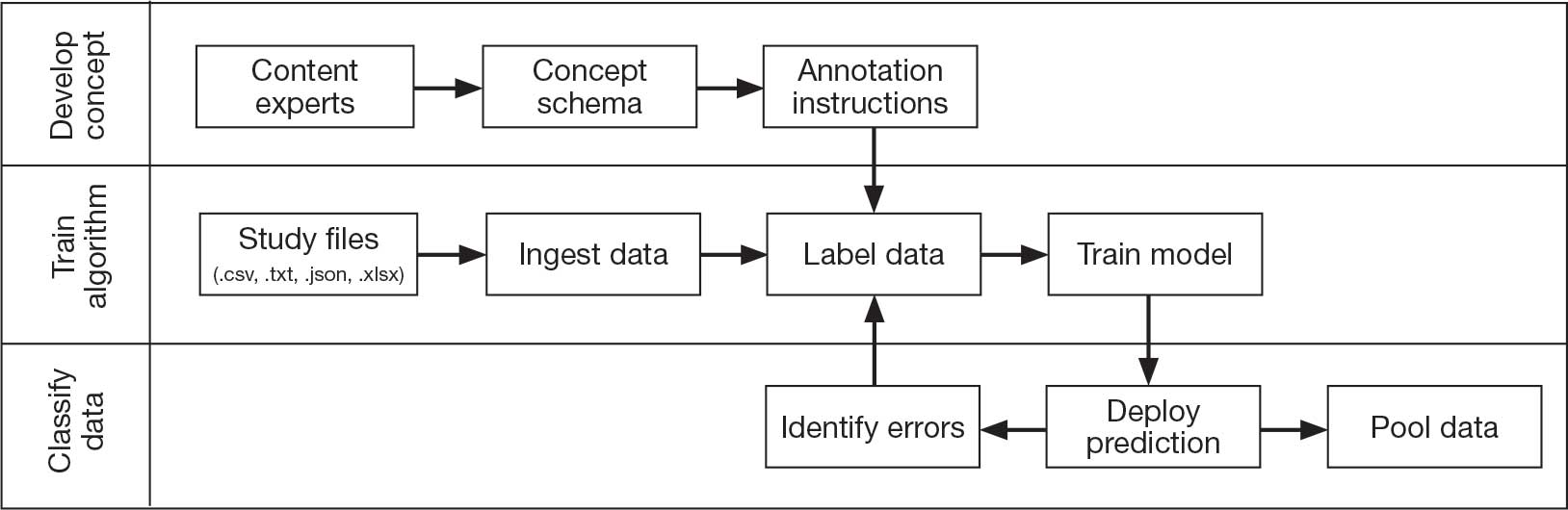

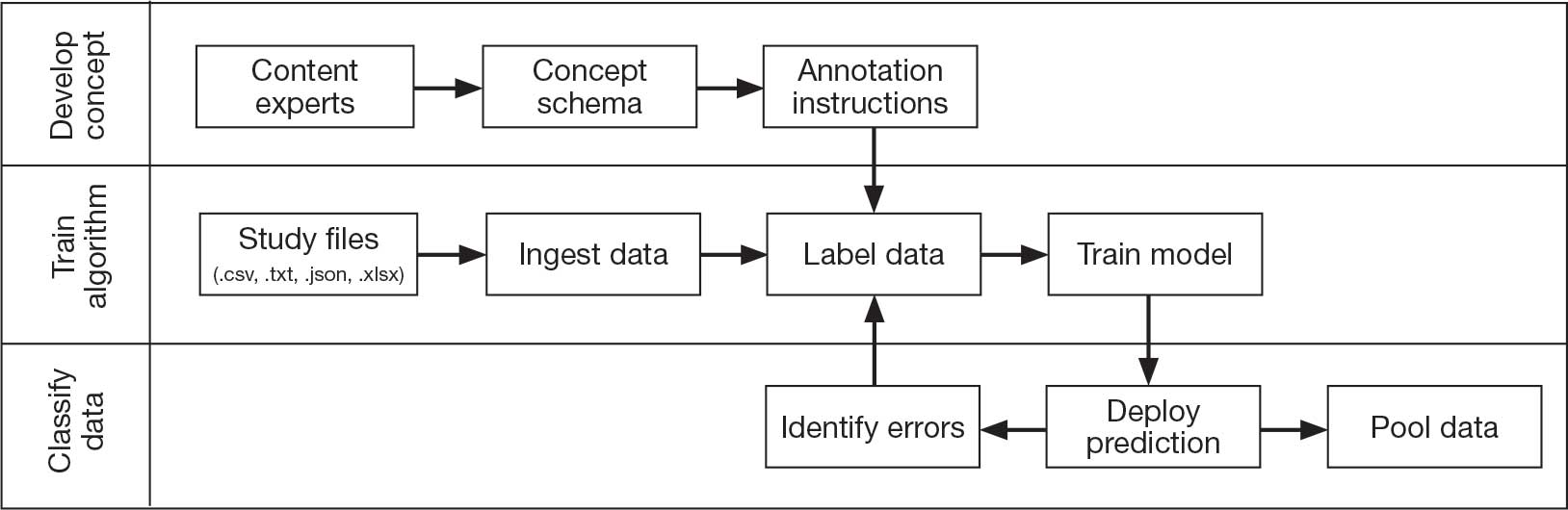

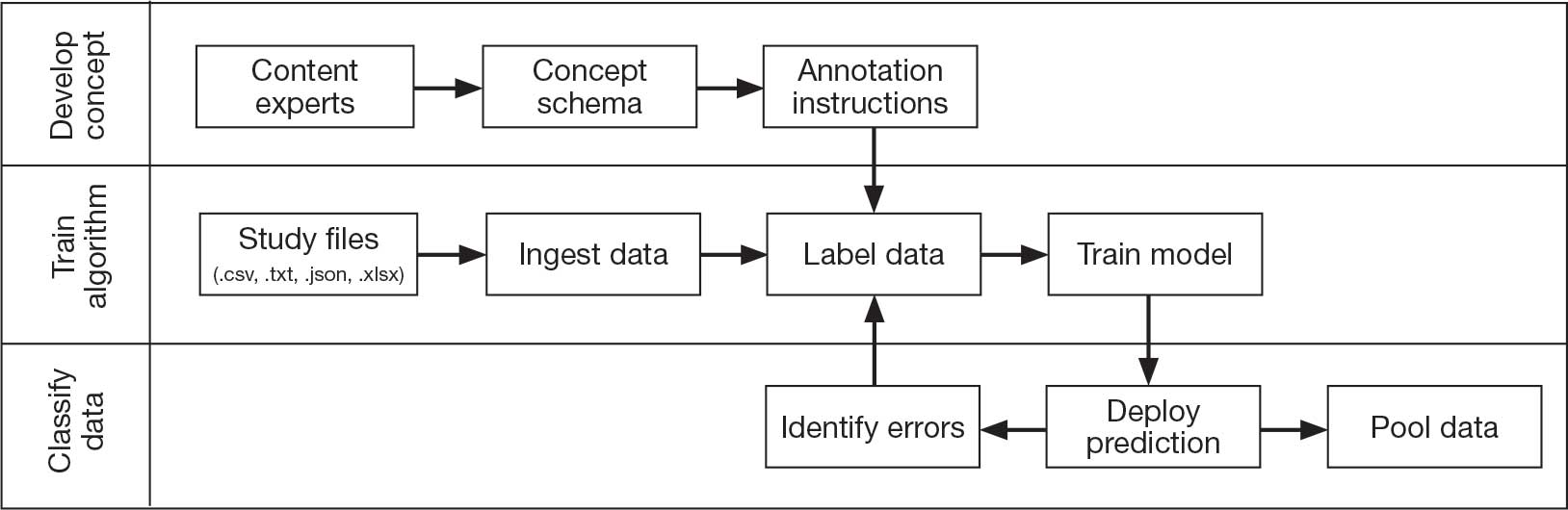

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

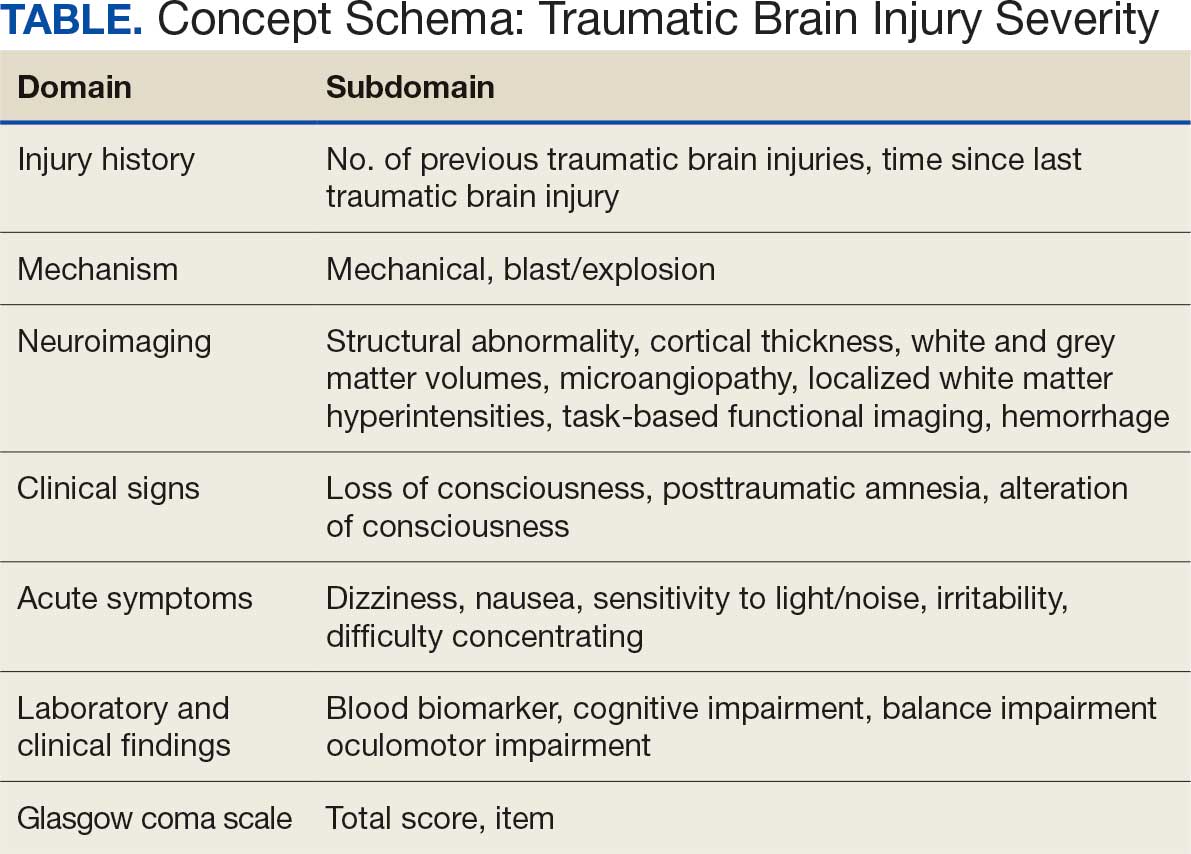

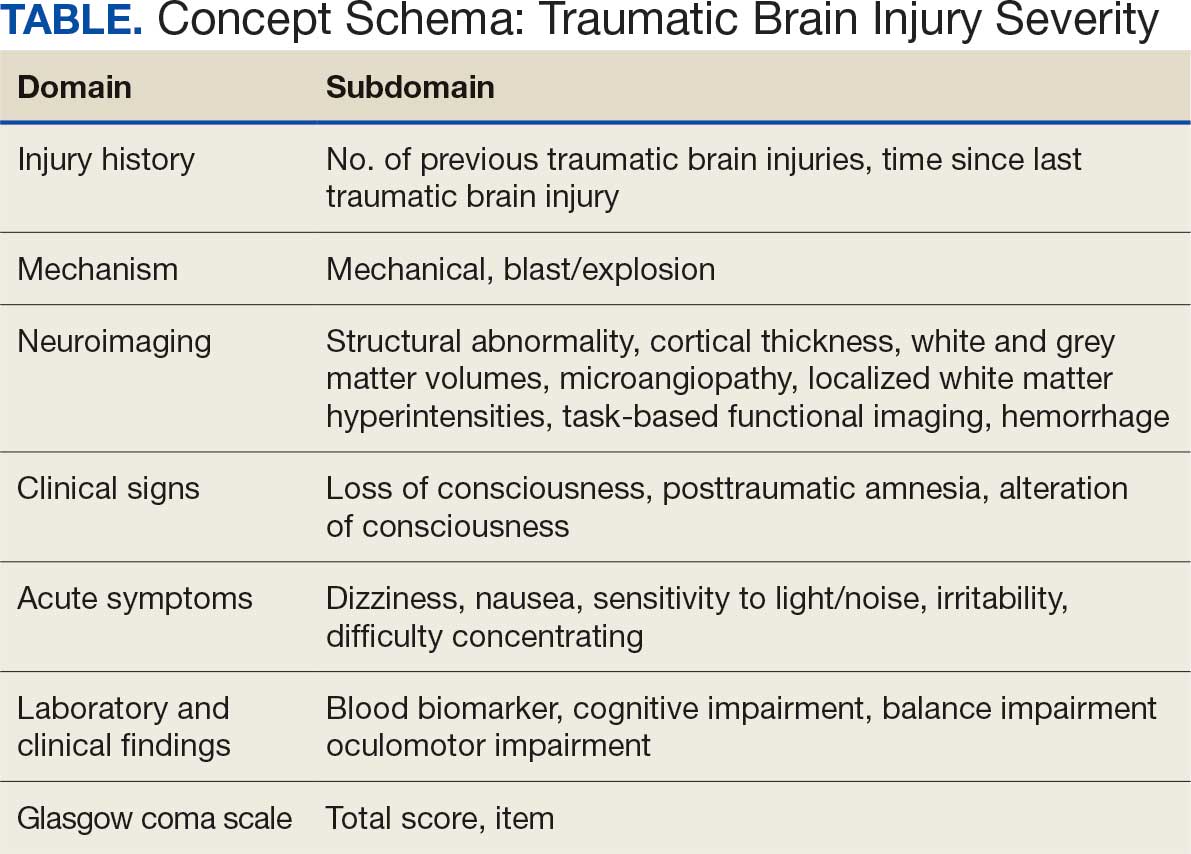

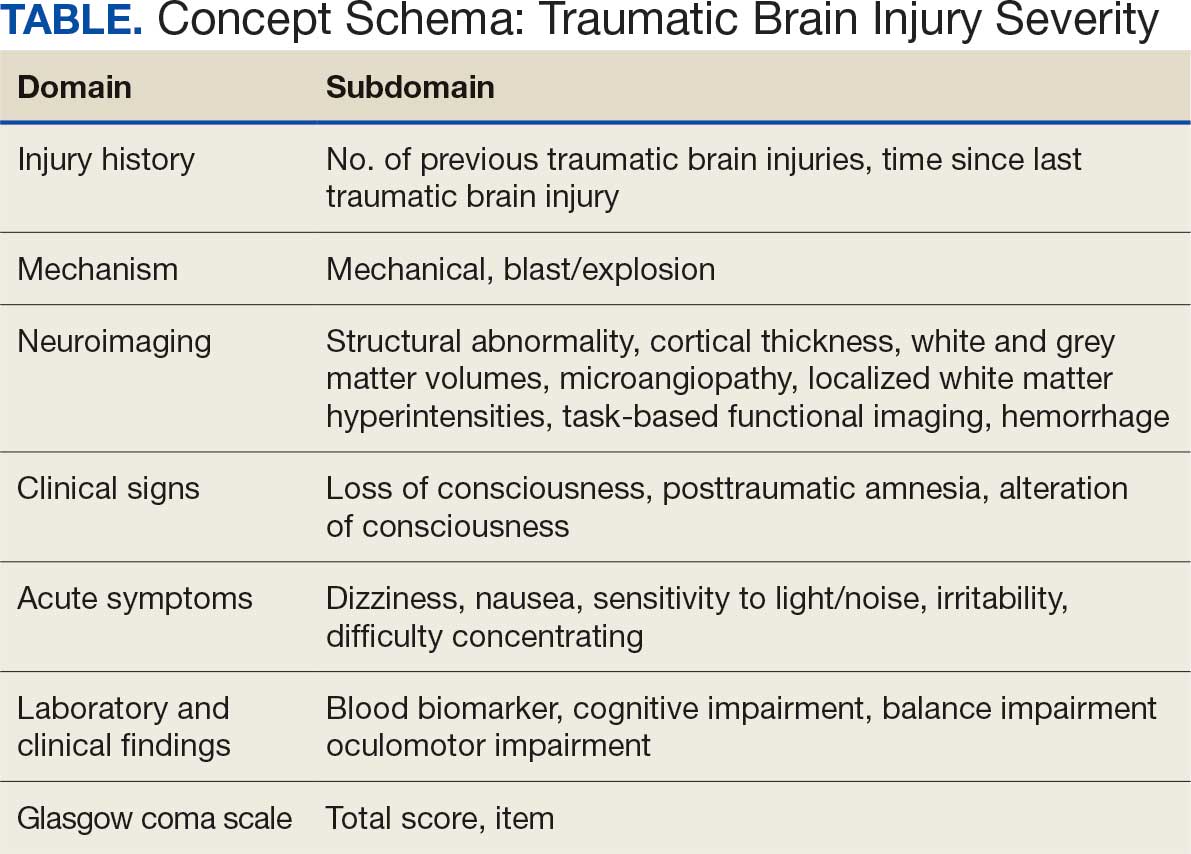

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

In leveraging existing, readily available evidence-based health care information (eg, systematic reviews, clinical practice guidelines), clinicians have historically made recommendations based on treatment responses of the average patient.1 Recently, this approach has been expanded into data-driven, evidence-based precision medical care for individuals across a wide range of disciplines and care settings. These precision medicine approaches use information related to an individual’s genes, environment, and lifestyle to tailor recommendations regarding prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Applying precision medicine approaches to the unique exposures and experiences of service members and veterans—particularly those who served in combat environments—through the incorporation of biopsychosocial factors into medical decision-making may be even more pertinent. This sentiment is reflected in Section 305 of the Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, which outlines the Precision Medicine Initiative of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify and validate brain and mental health biomarkers.2 Despite widespread consensus regarding the promise of precision medicine, large, rich datasets with elements pertaining to common military exposures such as traumatic brain injury (TBI) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are limited.

Existing datasets, most of which are relatively small or focus on specific cohorts (eg, older veterans, transitioning veterans), continue to create barriers to advancing precision medicine. For example, in classically designed clinical trials, analyses are generally conducted in a manner that may obfuscate efficacy among subcohorts of individuals, thereby underscoring the need to explore alternative strategies to unify existing datasets capable of revealing such heterogeneity.3 The evidence base for precision medical care is limited, drawing from published trials with relatively small sample sizes and even larger cohort studies have limited biomarker data. Additionally, these models are often exploratory during development, and to avoid statistical overfitting of an exploratory model, validation in similar datasets is needed—an added burden when data sources are small or underpowered to begin with.

A promising approach is to combine and harmonize the largest, most deeply characterized data sources from similar samples. Although combining such datasets may appear to require minimal time and effort, harmonizing similar variables in an evidence-based and replicable manner requires time and expertise, even when participant characteristics and outcomes are similar.4-7

Challenges related to harmonization are related to the wide range of strategies (eg, self-report questionnaires, clinical interviews, electronic health record review) used to measure common brain and mental health constructs, such as depression. Even when similar methods (eg, self-report measures) are implemented, challenges persist. For example, if a study used a depression measure that focused primarily on cognitive symptoms (eg, pessimism, self-dislike, suicidal ideation) and another study used a depression measure composed of items more heavily weighted towards somatic symptoms (eg, insomnia, loss of appetite, weight loss, decreased libido), combining their data could be challenging, particularly if researchers, clinicians, or administrators are interested in more than dichotomous outcomes (eg, depression vs no depression).8,9

To address this knowledge gap and harmonize multimodal data from varied sources, well-planned and reproducible curation is needed. Longitudinal cohort studies of service members and veterans with military combat and training exposure histories provide researchers and other stakeholders access to extant biopsychosocial data shown to affect risk for adverse health outcomes; however, efforts to facilitate individually tailored treatment or other precision medicine approaches would benefit from the synthesis of such datasets.10

Members of the VA Total Brain Diagnostics (TBD) team are engaged in harmonizing variables from the Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium–Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (LIMBIC-CENC)11 and the Translational Research Center for TBI and Stress Disorders (TRACTS).12-21 While there is overlap across LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS with respect to data domains, considerable data harmonization is needed to allow for future valid and meaningful analyses, particularly those involving multivariable predictors.

Data Sources

Both data sources for the TBD harmonization project, LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS, include extensive, longitudinal data collected from relatively large cohorts of veterans and service members with combat exposure. Both studies collect detailed data related to potential brain injury history and include participants with and without a history of TBI. Similarly, both include extensive collection of fluid biomarkers and imaging data, as well as measures of biopsychosocial functioning.

Data collection sites for LIMBIC-CENC include 16 recruitment sites, 9 at VA medical centers (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego) and 7 at military treatment sites (Alexandria, San Diego, Tampa, Tacoma, Columbia, Coronado, Hinesville), in addition to 11 assessment sites (Richmond, Houston, Tampa, San Antonio, Portland, Minneapolis, Boston, Salisbury, San Diego, Alexandria, Augusta). Data for TRACTS are collected at sites in Boston and Houston.

LIMBIC-CENC is a 12-year, 17-site cohort of service members and veteran participants with combat exposure who are well characterized at baseline and undergo annual reassessments. As of December 2025, > 3100 participants have been recruited, and nearly 90% remain in follow-up. Data collection includes > 6200 annual follow-up evaluations and > 1550 5-year re-evaluations, with 400 enrolled participants followed up annually.

TRACTS is a 16-year, 2-site cohort of veterans with combat exposure who complete comprehensive assessments at enrollment, undergo annual reassessments, and complete comprehensive reassessment every 5 years thereafter. As of December 2025, > 1075 participants have completed baseline (Time 1) assessments, > 600 have completed the 2-year re-evaluation (Time 2), > 175 have completed the 5-year re-evaluation (Time 3), and > 35 have completed 10-year evaluations (Time 4), with about 50 new participants added and 100 enrolled participants followed up annually. More data on participant characteristics are available for both LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS in previous publications.11,22These 2 ongoing, prospective, longitudinal cohorts of service members and veterans offer access to a wide range of potential risk factors that can affect response to care and outcomes, including demographics (eg, age, sex), injury characteristics (eg, pre-exposure factors, exposure factors), biomarkers (eg, serum, saliva, brain imaging, evoked potentials), and functional measures (eg, computerized posturography, computerized eye tracking, sensory testing, clinical examination, neuropsychological assessments, symptom questionnaires).

Harmonization Strategy

Pooling and harmonizing data from large studies evaluating similar participant cohorts and conditions involves numerous steps to appropriately handle a variety of measurements and disparate variable names. The TBD team adapted a model data harmonization system developed by O’Neil et al through initial work harmonizing the Federal Interagency Traumatic Brain Injury Research Informatics System (FITBIR).4-7 This process was expanded and generalized by the research team to combine data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to create a single pooled dataset for analysis (Figure).

Injury Research database.

This approach was selected because it accommodates heterogeneous study designs (eg, cross-sectional, longitudinal, case-control), data collection methods (eg, clinical assessment, self-reported, objective blood, and imaging biomarkers), and various assessments of the same construct (ie, different measures of brain injury). While exact matches for data collection methods and measures may be easily harmonized, the timing of assessment, number of assessments, assessment tool version, and other factors must be considered. The goal was to harmonize data from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS to allow additional data sources to be harmonized and incorporated in the future.

Original data files from each study were reshaped to represent participant-level observations with 1 unique measurement per row. The measurement represents what information was collected and the value recorded represents the unique observation. These data are linked to metadata from the original study, which includes the study’s definition of each measurement, how it was collected, and any available information regarding when it was collected in reference to study enrollment or injury. Additional information on the file source, row, and column position of each data point was added to enable recreation of the original data as needed.

The resulting dataset was used to harmonize measurements from LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS into a priori-defined schemas for brain- and mental health-relevant concepts, including TBI severity, PTSD, substance use, depression, suicidal ideation, and functioning (including cognitive, physical, and social functioning). This process was facilitated using natural language processing (NLP). Each study uniquely defines all measurements and provides written definitions with the data. Measurement definitions serve as records describing what was collected, how it was collected, and how the study may have uniquely defined information for its purposes. For example, definitions of exposure to brain injury and severity of brain injury may differ between studies, and the study-provided definition defines these differences.

Definitions were converted into numeric vectors through sentence embedding, a process that preserves the semantic meaning of the definition.23 Cosine similarity was used as the primary metric to compare the semantic textual similarity between pairs of measurement definitions. Cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no meaningful similarity and 1 indicates they have identical meanings.24 This approach leverages the relationship between the definitions of each measurement provided by a study and enables quick comparison of all pairwise combinations of measurement definitions between studies.

Subsets of similar measurements across studies were organized into a priori-defined schema. Clinical experts then reviewed each schema and further refined them into domains, (eg, mechanism of injury, clinical signs, acute symptoms) and subdomains (children), such as loss of consciousness, amnesia, and alteration of consciousness. This approach allows efficient handling of 2 specific cases that commonly occur when pooling and harmonizing datasets: (1) identifying the same measurement with differing names; and (2) identifying different measurements with definitions that each relate to the same domain.

The Table provides a general example of the schema for TBI severity. This was an iterative process in which clinical experts reviewed study-defined measurement definitions to develop general harmonized domains, and NLP techniques facilitated and accelerated identification and organization of measurements within these domains.

Expected Impact

Harmonization combining LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS datasets is ongoing. Preliminary descriptive analyses of baseline cohort data indicate that harmonization across data sources is appropriate, given the lack of significant heterogeneity across sites and studies for most domains. Work by members of the TBD team is expected to lay the foundation for the use of existing and ongoing prospective, longitudinal datasets (eg, LIMBIC-CENC, TRACTS) and linked large datasets (eg, VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure including electronic health records, VA Million Veteran Program, DaVINCI [US Department of Defense and VA Infrastructure for Clinical Intelligence]) to generate generalizable, clinically relevant information to advance precision brain and mental health care among service members and veterans.

By enhancing existing practice, this synthesized dataset has the potential to inform tailored and personalized medicine approaches designed to meet the needs of veterans and service members. These data will serve as the starting point for multivariable models examining the intersection of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors. The goal of this data harmonization effort is to better elucidate how clinicians and researchers can select optimal approaches for veterans and service members with TBI histories by accounting for a comprehensive set of physiologic, behavioral, and environmental factors in an individually tailored manner. These data may further extend existing clinical practice guideline approaches, inform shared decision-making, and enhance functional outcomes beyond those currently available.

Conclusions

Individuals who have served in the military have unique biopsychosocial exposures that are associated with brain and mental health disorders. To address these needs, the nationwide TBD team has initiated the creation of a unified, longitudinal dataset that includes harmonized measures from existing LIMBIC-CENC and TRACTS protocols. Initial data harmonization efforts are required to facilitate precision prognostics, diagnostics, and tailored interventions, with the goal of improving veterans’ brain and mental health and psychosocial functioning and enabling tailored and evidence-informed, individualized clinical care.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

- The Promise of Precision Medicine. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Updated January 21, 2025. Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-turning-discovery-into-health/promise-precision-medicine.

- Commander John Scott Hannon Veterans Mental Health Care Improvement Act of 2019, S 785, 116th Cong (2019-2020) Accessed January 5, 2026. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/785

- Cheng C, Messerschmidt L, Bravo I, et al. A general primer for data harmonization. Sci Data. 2024;11:152. doi:10.1038/s41597-024-02956-3

- Neil M, Cameron D, Clauss K, et al. A proof-of-concept study demonstrating how FITBIR datasets can be harmonized to examine posttraumatic stress disorder-traumatic brain injury associations. J Behav Data Sci. 2024;4:45-62. doi:10.35566/jbds/oneil

- O’Neil ME, Cameron D, Krushnic D, et al. Using harmonized FITBIR datasets to examine associations between TBI history and cognitive functioning. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. doi:10.1080/23279095.2024.2401974

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Clauss K, et al. Harmonizing federal interagency traumatic brain injury research data to examine depression and suicide-related outcomes. Rehabil Psychol. 2024;69:159-170. doi:10.1037/rep0000547

- O’Neil ME, Krushnic D, Walker WC, et al. Increased risk for clinically significant sleep disturbances in mild traumatic brain injury: an approach to leveraging the federal interagency traumatic brain injury research database. Brain Sci. 2024;14:921. doi:10.3390/brainsci14090921

- Uher R, Perlis RH, Placentino A, et al. Self-report and clinician-rated measures of depression severity: can one replace the other? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:1043-1049. doi:10.1002/da.21993

- Hung CI, Weng LJ, Su YJ, et al. Depression and somatic symptoms scale: a new scale with both depression and somatic symptoms emphasized. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60:700-708. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2006.01585.x

- Stewart IJ, Howard JT, Amuan ME, et al. Traumatic brain injury is associated with the subsequent risk of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2025;22:661-667. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2024.09.019

- Cifu DX. Clinical research findings from the long-term impact of military-relevant brain injury consortium-chronic effects of neurotrauma consortium (LIMBIC-CENC) 2013-2021. Brain Inj. 2022;36:587-597.doi:10.1080/02699052.2022.2033843

- Fonda JR, Fredman L, Brogly SB, et al. Traumatic brain injury and attempted suicide among veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:220-226. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx044

- Fortier CB, Amick MM, Kenna A, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime (BAT-L) clinical interview and the VA TBI screen. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015;30:E1-7. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000008

- Grande LJ, Robinson ME, Radigan LJ, et al. Verbal memory deficits in OEF/OIF/OND veterans exposed to blasts at close range. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2018;24:466-475. doi:10.1017/S1355617717001242

- Hayes JP, Logue MW, Sadeh N, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury is associated with reduced cortical thickness in those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:813-825. doi:10.1093/brain/aww344

- Lippa SM, Fonda JR, Fortier CB, et al. Deployment-related psychiatric and behavioral conditions and their association with functional disability in OEF/OIF/OND veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:25-33. doi:10.1002/jts.21979

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, et al. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudinal prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Radigan LJ, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, et al. Correspondence of the Boston Assessment of Traumatic Brain Injury-Lifetime and the VA Comprehensive TBI Evaluation. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E55. doi:10.1097/htr.0000000000000361

- Sydnor VJ, Bouix S, Pasternak O, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury impacts associations between limbic system microstructure and post-traumatic stress disorder symptomatology. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102190. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102190

- Van Etten EJ, Knight AR, Colaizzi TA, et al. Peritraumatic context and long-term outcomes of concussion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8:e2455622. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.55622

- Andrews RJ, Fonda JR, Levin LK, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the predictors of neurobehavioral symptom reporting in veterans. Neurology. 2018;91:e732-e745. doi:10.1212/wnl.0000000000006034

- McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP, Fonda JR, Fortier CB. A methodology for assessing deployment trauma and its consequences in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: the TRACTS longitudional prospective cohort study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1556. doi:10.1002/mpr.1556

- Reimers N, Gurevych I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. 2019. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Singhal A. Modern information retrieval: a brief overview. IEEE Data Eng Bull. 2001;24:34-43.

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Total Brain Diagnostics: Advancing Precision Brain and Mental Health at the Department of Veterans Affairs

Trauma, Military Fitness, and Eating Disorders

Military culture may hold 2 salient risk factors for eating disorders: exposure to trauma and body condition standards. A recent study from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Salisbury Health Care System (VASHCS) found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more likely to report eating disturbances—particularly issues related to body dissatisfaction and dissatisfaction with eating habits. A 2019 study found that one-third of veterans who were overweight or obese screened positive for engaging in “making weight” behaviors during military service, or unhealthy weight control strategies. Frequently reported weight management behavior was excessive exercise, fasting/skipping meals, sitting in a sauna/wearing a latex suit, laxatives, diuretics, and vomiting.

Service members who are “normal” weight by civilian standards may be labeled “overweight” by the military. In a March 12 memo, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth ordered a US Department of Defense review of existing standards for physical fitness, body composition, and grooming. “Our troops will be fit — not fat. Our troops will look sharp — not sloppy. We seek only quality — not quotas. BOTTOM LINE: our @DeptofDefense will make standards HIGH & GREAT again — across the entire force,” he posted on X.

The desire to control weight to fit military standards, however, isn’t the only risk factor. Researchers at VASHCS surveyed 527 post-9/11 veterans (80.7% male) who typically deployed 1 or 2 times. All participants completed the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; the Neuro-Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Positive Affect and Well-Being Scale (PAWB); and the Eating Disturbances Scale.

Nearly half (46%) of the sample met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime PTSD diagnosis. The study also reported significantly greater eating disturbances in veterans with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis than those without. Women reported significantly greater eating disturbances than men.

Most participants (80%) reported some level of dissatisfaction with their eating disturbances and 74% of participants reported feeling as if they were too fat.

Eating disturbances include refusing food, overexercising, overeating, and misusing laxatives or diuretic pills. Previous research that suggest that 10% to 15% of female veterans and 4% to 8% of male veterans report clinically significant disordered eating behaviors, especially binge eating. One study found that 78% of 45,477 overweight or obese veterans receiving care in VA facilities reported clinically significant binge eating. In a 2021 study, 254 veterans presenting for routine clinical care completed self‐report questionnaires assessing eating disorders, PTSD, depression, and shame, and 31% met probable criteria for bulimia nervosa, binge‐eating disorder, or purging disorder.

According to a 2023 study, eating disturbances that do not meet diagnostic criteria for a formal disorder can be problematic and may function as coping strategies for some facets of military life. The VASHCS researchers found that interventions focused on PAWB, such as acceptance and commitment therapy or compassion-focused therapy, may have potential as a protective factor. Including components that foster hope, optimism, and personal strength may positively mitigate the relationship between PTSD and eating disturbances. PAWB was significantly correlated with eating disturbances; individuals with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis reported significantly lower PAWB than those without.

Interventions grounded in positive psychology have shown promise. A group-based program found “noticeable” (although nonsignificant) improvements in optimistic thinking and treatment engagement. The study also cites that clinicians are beginning to incorporate positive psychology strategies (eg, gratitude journaling, goal setting, and “best possible self” visualization) as adjuncts to traditional treatments. Positive psychology, they write, holds “significant promise as a complementary approach to enhance recovery outcomes in both PTSD and eating disorders.”

Military culture may hold 2 salient risk factors for eating disorders: exposure to trauma and body condition standards. A recent study from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Salisbury Health Care System (VASHCS) found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more likely to report eating disturbances—particularly issues related to body dissatisfaction and dissatisfaction with eating habits. A 2019 study found that one-third of veterans who were overweight or obese screened positive for engaging in “making weight” behaviors during military service, or unhealthy weight control strategies. Frequently reported weight management behavior was excessive exercise, fasting/skipping meals, sitting in a sauna/wearing a latex suit, laxatives, diuretics, and vomiting.

Service members who are “normal” weight by civilian standards may be labeled “overweight” by the military. In a March 12 memo, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth ordered a US Department of Defense review of existing standards for physical fitness, body composition, and grooming. “Our troops will be fit — not fat. Our troops will look sharp — not sloppy. We seek only quality — not quotas. BOTTOM LINE: our @DeptofDefense will make standards HIGH & GREAT again — across the entire force,” he posted on X.

The desire to control weight to fit military standards, however, isn’t the only risk factor. Researchers at VASHCS surveyed 527 post-9/11 veterans (80.7% male) who typically deployed 1 or 2 times. All participants completed the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; the Neuro-Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Positive Affect and Well-Being Scale (PAWB); and the Eating Disturbances Scale.

Nearly half (46%) of the sample met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime PTSD diagnosis. The study also reported significantly greater eating disturbances in veterans with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis than those without. Women reported significantly greater eating disturbances than men.

Most participants (80%) reported some level of dissatisfaction with their eating disturbances and 74% of participants reported feeling as if they were too fat.

Eating disturbances include refusing food, overexercising, overeating, and misusing laxatives or diuretic pills. Previous research that suggest that 10% to 15% of female veterans and 4% to 8% of male veterans report clinically significant disordered eating behaviors, especially binge eating. One study found that 78% of 45,477 overweight or obese veterans receiving care in VA facilities reported clinically significant binge eating. In a 2021 study, 254 veterans presenting for routine clinical care completed self‐report questionnaires assessing eating disorders, PTSD, depression, and shame, and 31% met probable criteria for bulimia nervosa, binge‐eating disorder, or purging disorder.

According to a 2023 study, eating disturbances that do not meet diagnostic criteria for a formal disorder can be problematic and may function as coping strategies for some facets of military life. The VASHCS researchers found that interventions focused on PAWB, such as acceptance and commitment therapy or compassion-focused therapy, may have potential as a protective factor. Including components that foster hope, optimism, and personal strength may positively mitigate the relationship between PTSD and eating disturbances. PAWB was significantly correlated with eating disturbances; individuals with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis reported significantly lower PAWB than those without.

Interventions grounded in positive psychology have shown promise. A group-based program found “noticeable” (although nonsignificant) improvements in optimistic thinking and treatment engagement. The study also cites that clinicians are beginning to incorporate positive psychology strategies (eg, gratitude journaling, goal setting, and “best possible self” visualization) as adjuncts to traditional treatments. Positive psychology, they write, holds “significant promise as a complementary approach to enhance recovery outcomes in both PTSD and eating disorders.”

Military culture may hold 2 salient risk factors for eating disorders: exposure to trauma and body condition standards. A recent study from the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Salisbury Health Care System (VASHCS) found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are more likely to report eating disturbances—particularly issues related to body dissatisfaction and dissatisfaction with eating habits. A 2019 study found that one-third of veterans who were overweight or obese screened positive for engaging in “making weight” behaviors during military service, or unhealthy weight control strategies. Frequently reported weight management behavior was excessive exercise, fasting/skipping meals, sitting in a sauna/wearing a latex suit, laxatives, diuretics, and vomiting.

Service members who are “normal” weight by civilian standards may be labeled “overweight” by the military. In a March 12 memo, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth ordered a US Department of Defense review of existing standards for physical fitness, body composition, and grooming. “Our troops will be fit — not fat. Our troops will look sharp — not sloppy. We seek only quality — not quotas. BOTTOM LINE: our @DeptofDefense will make standards HIGH & GREAT again — across the entire force,” he posted on X.

The desire to control weight to fit military standards, however, isn’t the only risk factor. Researchers at VASHCS surveyed 527 post-9/11 veterans (80.7% male) who typically deployed 1 or 2 times. All participants completed the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; the Neuro-Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Positive Affect and Well-Being Scale (PAWB); and the Eating Disturbances Scale.

Nearly half (46%) of the sample met diagnostic criteria for a lifetime PTSD diagnosis. The study also reported significantly greater eating disturbances in veterans with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis than those without. Women reported significantly greater eating disturbances than men.

Most participants (80%) reported some level of dissatisfaction with their eating disturbances and 74% of participants reported feeling as if they were too fat.

Eating disturbances include refusing food, overexercising, overeating, and misusing laxatives or diuretic pills. Previous research that suggest that 10% to 15% of female veterans and 4% to 8% of male veterans report clinically significant disordered eating behaviors, especially binge eating. One study found that 78% of 45,477 overweight or obese veterans receiving care in VA facilities reported clinically significant binge eating. In a 2021 study, 254 veterans presenting for routine clinical care completed self‐report questionnaires assessing eating disorders, PTSD, depression, and shame, and 31% met probable criteria for bulimia nervosa, binge‐eating disorder, or purging disorder.

According to a 2023 study, eating disturbances that do not meet diagnostic criteria for a formal disorder can be problematic and may function as coping strategies for some facets of military life. The VASHCS researchers found that interventions focused on PAWB, such as acceptance and commitment therapy or compassion-focused therapy, may have potential as a protective factor. Including components that foster hope, optimism, and personal strength may positively mitigate the relationship between PTSD and eating disturbances. PAWB was significantly correlated with eating disturbances; individuals with a lifetime PTSD diagnosis reported significantly lower PAWB than those without.

Interventions grounded in positive psychology have shown promise. A group-based program found “noticeable” (although nonsignificant) improvements in optimistic thinking and treatment engagement. The study also cites that clinicians are beginning to incorporate positive psychology strategies (eg, gratitude journaling, goal setting, and “best possible self” visualization) as adjuncts to traditional treatments. Positive psychology, they write, holds “significant promise as a complementary approach to enhance recovery outcomes in both PTSD and eating disorders.”

'Distress is the Norm': How Oncologists Can Open the Door to Patient Mental Health

'Distress is the Norm': How Oncologists Can Open the Door to Patient Mental Health

For patients with cancer, the determining factor in whether they pursue mental health services is often whether their oncologist explicitly says it is a good idea, a psychologist said during the July Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) seminar in Long Beach, California, on treating veterans with renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Kysa Christie, PhD, of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, presented findings from a 2018 study in which researchers asked Swiss patients with cancer whether their oncologist discussed their emotional health with them.

In terms of boosting intake, it did not matter if oncologists acknowledged distress or pointed out that psychosocial services existed. Instead, a direct recommendation made a difference, increasing the likelihood of using the services over a 4-month period after initial assessment (odds ratio, 6.27).

“What it took was, ‘I really recommend this. This is something that I would want you to try,’” Christie said.

Oncologists are crucial links between patients and mental health services, Christie said: “If people don’t ask about [distress], you’re not going to see it, but it’s there. Distress is the norm, right? It is not a weakness. It is something that we expect to see.”

Christie noted that an estimated 20% of cancer patients have major depressive disorder, and 35% to 40% have a diagnosable psychiatric condition. RCC shows disproportionately high rates of mental strain. According to Christie, research suggests that about three-fourths of the population report elevated levels of distress as evidenced by patients who scored ≥ 5 on the NCCN Distress Thermometer. Patients with cancer have an estimated 20% higher risk of suicide, especially during the first 12 months after diagnosis and at end of life, she added.

“Early during a diagnosis phase, where you’re having a lot of tests being done, you know something is happening. But you don’t know what,” Christie said. “It could be very serious. That’s just a lot of stress to hold and not know how to plan for.”

After diagnosis, routine could set in and lower distress, she said. Then terminal illness may spike it back up again. Does mental health treatment work in patients with cancer?

“There’s a really strong body of evidence-based treatments for depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders, and coping with different cancers,” Christie said. But it is a step too far to expect patients to ask for help while they are juggling appointments, tests, infusions, and more. “It’s a big ask, right? It’s setting people up for failure.”

To help, Christie said she is embedded with a medical oncology team and routinely talks with the staff about which patients may need help. “One thing I like to do is try to have brief visits with veterans and introduce myself when they come to clinic. I treat it like an opt-out rather than an opt-in program: I’ll just pop into the exam room. They don’t have to ask to see me.”

Christie focuses on open-ended questions and talks about resources ranging from support groups and brief appointments to extensive individual therapy.

Another approach is a strategy known as the “warm handoff,” when an oncologist directly introduces a patient to a mental health professional. “It’s a transfer of care in front of the veteran: It’s much more time-efficient than putting in a referral.”

Christie explained how this can work. A clinician will ask her to meet with a patient during an appointment, perhaps in a couple minutes.

“Then I pop into the room, and the oncologist says, ‘Thanks for joining us. This is Mr. Jones. He has been experiencing feelings of anxiety and sadness, and we’d appreciate your help in exploring some options that might help.’ I turn to the patient and ask, ‘What more would you add?’ Then I either take Mr. Jones back to my office or stay in clinic, and we’re off to the races.”

Christie reported no disclosures.

For patients with cancer, the determining factor in whether they pursue mental health services is often whether their oncologist explicitly says it is a good idea, a psychologist said during the July Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) seminar in Long Beach, California, on treating veterans with renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Kysa Christie, PhD, of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, presented findings from a 2018 study in which researchers asked Swiss patients with cancer whether their oncologist discussed their emotional health with them.

In terms of boosting intake, it did not matter if oncologists acknowledged distress or pointed out that psychosocial services existed. Instead, a direct recommendation made a difference, increasing the likelihood of using the services over a 4-month period after initial assessment (odds ratio, 6.27).

“What it took was, ‘I really recommend this. This is something that I would want you to try,’” Christie said.

Oncologists are crucial links between patients and mental health services, Christie said: “If people don’t ask about [distress], you’re not going to see it, but it’s there. Distress is the norm, right? It is not a weakness. It is something that we expect to see.”

Christie noted that an estimated 20% of cancer patients have major depressive disorder, and 35% to 40% have a diagnosable psychiatric condition. RCC shows disproportionately high rates of mental strain. According to Christie, research suggests that about three-fourths of the population report elevated levels of distress as evidenced by patients who scored ≥ 5 on the NCCN Distress Thermometer. Patients with cancer have an estimated 20% higher risk of suicide, especially during the first 12 months after diagnosis and at end of life, she added.

“Early during a diagnosis phase, where you’re having a lot of tests being done, you know something is happening. But you don’t know what,” Christie said. “It could be very serious. That’s just a lot of stress to hold and not know how to plan for.”

After diagnosis, routine could set in and lower distress, she said. Then terminal illness may spike it back up again. Does mental health treatment work in patients with cancer?

“There’s a really strong body of evidence-based treatments for depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders, and coping with different cancers,” Christie said. But it is a step too far to expect patients to ask for help while they are juggling appointments, tests, infusions, and more. “It’s a big ask, right? It’s setting people up for failure.”

To help, Christie said she is embedded with a medical oncology team and routinely talks with the staff about which patients may need help. “One thing I like to do is try to have brief visits with veterans and introduce myself when they come to clinic. I treat it like an opt-out rather than an opt-in program: I’ll just pop into the exam room. They don’t have to ask to see me.”

Christie focuses on open-ended questions and talks about resources ranging from support groups and brief appointments to extensive individual therapy.

Another approach is a strategy known as the “warm handoff,” when an oncologist directly introduces a patient to a mental health professional. “It’s a transfer of care in front of the veteran: It’s much more time-efficient than putting in a referral.”

Christie explained how this can work. A clinician will ask her to meet with a patient during an appointment, perhaps in a couple minutes.

“Then I pop into the room, and the oncologist says, ‘Thanks for joining us. This is Mr. Jones. He has been experiencing feelings of anxiety and sadness, and we’d appreciate your help in exploring some options that might help.’ I turn to the patient and ask, ‘What more would you add?’ Then I either take Mr. Jones back to my office or stay in clinic, and we’re off to the races.”

Christie reported no disclosures.

For patients with cancer, the determining factor in whether they pursue mental health services is often whether their oncologist explicitly says it is a good idea, a psychologist said during the July Association of VA Hematology and Oncology (AVAHO) seminar in Long Beach, California, on treating veterans with renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

Kysa Christie, PhD, of the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, presented findings from a 2018 study in which researchers asked Swiss patients with cancer whether their oncologist discussed their emotional health with them.

In terms of boosting intake, it did not matter if oncologists acknowledged distress or pointed out that psychosocial services existed. Instead, a direct recommendation made a difference, increasing the likelihood of using the services over a 4-month period after initial assessment (odds ratio, 6.27).

“What it took was, ‘I really recommend this. This is something that I would want you to try,’” Christie said.

Oncologists are crucial links between patients and mental health services, Christie said: “If people don’t ask about [distress], you’re not going to see it, but it’s there. Distress is the norm, right? It is not a weakness. It is something that we expect to see.”