User login

Attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and often quoted in contemporary times, is the expression “the only constant is change.” This sentiment rings true for the field of obstetrics this past year, as several bread-and-butter guidelines for managing common obstetric conditions were either challenged or altered.

The publication of the PROLONG trial called into question the use of intramuscular progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth. Prophylaxis guidelines for group B streptococcal disease were updated, including several significant clinical practice changes. Finally, there was a comprehensive overhaul of the guidelines for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which replaced a landmark Task Force document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that was published only a few years ago.

Change is constant, and in obstetrics it is vital to keep up with the changing guidelines that result as new data become available for digestion and implementation into everyday clinical practice.

Results from the PROLONG trial may shake up treatment options for recurrent preterm birth

Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

The drug 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC, or 17P; Makena) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB) in women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of singleton spontaneous PTB. The results of the trial by Meis and colleagues of 17-OHPC played a major role in achieving that approval, as it demonstrated a 34% reduction in recurrent PTB and a reduction in some neonatal morbidities.1 Following the drug's approval, both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) published guidelines recommending progesterone therapy, including 17-OHPC, for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous PTB.2

The FDA approval of 17-OHPC was granted under an accelerated conditional pathway that required a confirmatory trial evaluating efficacy, safety, and long-term infant follow-up to be performed by the sponsor. That trial, Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation (PROLONG), was started in 2009, and its results were published on October 25, 2019.3

Continue to: Design of the trial...

Design of the trial

PROLONG was a multicenter (93 sites), randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 9 countries (23% of participants were in the United States, 60% were in Russia and Ukraine). The co-primary outcome was PTB < 35 weeks and a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality index. The primary safety outcome was fetal/early infant death.

The study was designed to have 98% power to detect a 30% reduction in PTB < 35 weeks, and 90% power to detect a 35% reduction in the neonatal composite index. It included 1,708 participants (1,130 were treated with 17-OHPC, and 578 received placebo).

Trial outcomes. There was no difference in PTB < 35 weeks between the 17-OHPC and the placebo groups (11.0% vs 11.5%; relative risk [RR], 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71-1.26). There was no difference in PTB < 32 or < 37 weeks.

The study revealed also that there was no difference between groups in the neonatal composite index (5.6% for 17-OHPC vs 5.0% for placebo; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). In addition, there was no difference in fetal/early infant death between the 17-OHPC and placebo groups (1.7% vs 1.9%; RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.4-1.81).

Conclusions. The trial investigators concluded that 17-OHPC did not demonstrate a reduction in recurrent PTB and did not decrease neonatal morbidity.

Study limitations included underpowering and selection bias

The investigators noted that the PTB rate in PROLONG was unexpectedly almost 50% lower than that in the Meis trial, and that therefore the PROLONG trial was underpowered to assess the primary outcomes.

Further, the study populations of the 2 trials were very different: The Meis trial included women at higher baseline risk for PTB (> 1 prior PTB and at least 1 other risk factor for PTB). Additionally, while the PROLONG trial included mostly white (90%), married (90%), nonsmoking women (8% smoked), the Meis trial population was 59% black and 50% married, and 20% were smokers.

The availability and common use of 17-OHPC in the United States likely led to a selection bias for the PROLONG trial population, as the highest-risk patients were most likely already receiving treatment and were therefore excluded from the PROLONG trial.

Society, and FDA, responses to the new data

The results of the PROLONG trial call into question what has become standard practice for patients with a history of spontaneous PTB in the United States. While the safety profile of 17-OHPC has not been cited as a concern, whether or not the drug should be used at all has—as has its current FDA-approved status.

In response to the publication of the PROLONG trial results, ACOG released a Practice Advisory that acknowledged the study's findings but did not alter the current recommendations to continue to offer progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, upholding ACOG's current Practice Bulletin guidance.2,4 Additional considerations for offering 17-OHPC use include the patients' preferences, available resources, and the setting for the intervention.

SMFM's response was more specific, stating that it is reasonable to continue to use 17-OHPC in high-risk patient populations consistent with those in the Meis trial.5 In the rest of the general population at risk for recurrent PTB, SMFM recommends that, due to uncertain benefit with 17-OHPC, the high cost, patient discomfort, and increased visits should be taken into account.

Four days after the publication of the PROLONG study, the FDA Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17-OHPC.6 In response, SMFM released a statement supporting continued access to 17-OHPC.7 The FDA's final decision on the status of the drug is expected within the next several months from this writing.

17-OHPC continues to be considered safe and still is recommended by both ACOG and SMFM for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth in high-risk patients. The high-risk patient population who may benefit most from this therapy is still not certain, but hopefully future studies will better delineate this. The landscape for 17-OHPC use may change dramatically if FDA approval is not upheld in the future. In my current practice, I am continuing to offer 17-OHPC to patients per the current ACOG guidelines, but I am counseling patients in a shared decision-making model regarding the findings of the PROLONG trial and the potential change in FDA approval.

Continue to: ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease...

ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

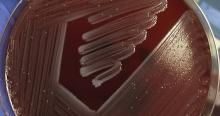

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of newborn infection and is associated with maternal infections as well as preterm labor and stillbirth. Early-onset GBS disease occurs within 7 days of birth and is linked to vertical transmission via maternal colonization of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract and fetal/neonatal aspiration at birth.

Preventing early-onset GBS disease with maternal screening and intrapartum prophylaxis according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines has reduced early-onset disease by 80% since the 1990s. By contrast, late-onset GBS infection, which occurs 7 days to 3 months after birth, usually is associated with horizontal maternal transmission or hospital or community infections, and it is not prevented by intrapartum treatment.

In 2018, the CDC transferred responsibility for GBS prophylaxis guidelines to ACOG and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In July 2019, ACOG released its Committee Opinion on preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns.8 This guidance replaces and updates the previous guidelines, with 3 notable changes.

The screening timing has changed

In the CDC's 2010 guidelines, GBS screening was recommended to start at 35 weeks' gestation. The new guidelines recommend universal vaginal-rectal screening at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation. The new timing of culture will shift the expected 5-week window in which GBS cultures are considered valid up to at least 41 weeks' gestation. The rationale for this change is that any GBS-unknown patient who previously would have been cultured under 37 weeks' would be an automatic candidate for empiric therapy and the lower rate of birth in the 35th versus the 41st week of gestation.

Identifying candidates for intrapartum treatment

The usual indications for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis include a GBS-positive culture at 36 weeks or beyond, GBS bacteriuria at any point in pregnancy, a prior GBS-affected child, or unknown GBS status with any of the following: < 37 weeks, rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours or temperature ≥ 100.4°F (38°C), and a positive rapid GBS culture in labor. In addition, antibiotics now should be considered for patients at term with unknown GBS status but with a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

This represents a major practice change for women at ≥ 37 weeks with unknown GBS status and no other traditional risk factors. The rationale for this recommendation is that women who have been positive for GBS in a prior pregnancy have a 50% chance of being colonized in the current pregnancy, and their newborns are therefore at higher risk for early-onset GBS disease.

Managing patients with penicillin allergy

Intravenous penicillin (or ampicillin) remains the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis against GBS due to its efficacy and specific, narrow coverage of gram-positive organisms. The updated recommendations emphasize that it is important to carefully evaluate patients with reported penicillin allergies for several reasons: determining risk of anaphylaxis and clindamycin susceptibility testing in GBS evaluations are often overlooked by obstetric providers, the need for antibiotic stewardship to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance, and clarification of allergy status for future health care needs.

Three recommendations are made:

- Laboratory requisitions for cultures should specifically note a penicillin allergy so that clindamycin susceptibility testing can be performed.

- Penicillin allergy skin testing should be considered for patients at unknown or low risk for anaphylaxis, as it is considered safe in pregnancy and most patients (80%-90%) who report a penicillin allergy are actually penicillin tolerant.

- For patients at high risk for anaphylaxis to penicillin, the recommended vancomycin dosing has been changed from 1 g IV every 12 hours to 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g). Renal function should be assessed prior to dosing. This weight- and renal function-based dosing increased neonatal therapeutic levels in several studies of different doses.

ACOG's key recommendations for preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns include:

- Universal vaginal-rectal screening for GBS should be performed at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for low-risk patients at term with unknown GBS status and a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

- Patients with a reported penicillin allergy require careful evaluation of the nature of their allergy, including consideration of skin testing and GBS susceptibility evaluation in order to promote the best practices for antibiotic use.

- For GBS-positive patients at high risk for penicillin anaphylaxis, vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g) is recommended.

Continue to: Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations...

Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

In 2013, ACOG released "Hypertension in pregnancy," a 99-page comprehensive document developed by their Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy, to summarize knowledge on the subject, provide guidelines for management, and identify needed areas of research.9 I summarized key points from that document in the 2014 "Update on Obstetrics" (OBG Manag. 2013;26[1]:28-36). Now, ACOG has released 2 Practice Bulletins—"Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia" and "Chronic hypertension in pregnancy"—that replace the 2013 document.10,11 These Practice Bulletins are quite comprehensive and warrant a thorough read. Several noteworthy changes relevant to the practicing obstetrician are summarized below.

Highlights of revised guidance

Expectant management vs early delivery in preeclampsia with fetal growth restriction. Fetal growth restriction, which was removed from the definition of preeclampsia with severe features in 2013, is no longer an indication for delivery in preeclampsia with severe features (previously, if the estimated fetal weight was < 5th percentile for gestational age, delivery after steroid administration was recommended). Rather, expectant management is reasonable if fetal antenatal testing, amniotic fluid, and Doppler ultrasound studies are reassuring. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies continue to be an indication for earlier delivery.

Postpartum NSAID use in hypertension. The 2013 document cautioned against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use postpartum in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy because of concern for exacerbating hypertension. The updated Practice Bulletins recommend NSAIDs as the preferred choice over opioid analgesics as data have not shown these drugs to increase blood pressure, antihypertensive requirements, or other adverse events in postpartum patients with blood pressure issues.

More women will be diagnosed with chronic hypertension. Recently, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association changed the definition of hypertension. Stage 1 hypertension is now defined as a systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of 80-89 mm Hg. Treatment of stage 1 hypertension is recommended for nonpregnant adults with risk factors for current or future cardiovascular disease. The potential impact is that more women will enter pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, and more may be on prepregnancy antihypertensive therapy that will need to be addressed during the pregnancy.

Blood pressure goals. The target blood pressure range for pregnant women with chronic hypertension is recommended to be ≥ 120/80 mm Hg and < 160/110 mm Hg (this represents a slight change, as previously diastolic blood pressure was to be < 105 mm Hg). Postpartum blood pressure goals of < 150/100 mm Hg remain the same.

Managing acute hypertensive emergencies. Both Practice Bulletins emphasize the importance of aggressive management of acute hypertensive emergency, with options for 3 protocols: labetalol, nifedipine, and hydralazine. The goal is to administer antihypertensive therapy within 30 to 60 minutes, but administration as soon as feasibly possible after diagnosis of severe hypertension is ideal.

Timing of delivery. Recommended delivery timing in patients with chronic hypertension was slightly altered (previous recommendations included a range of 37 to 39 6/7 weeks). The lower limit of gestational age for recommended delivery timing in chronic hypertension has not changed—it remains not before 38 weeks if no antihypertensive therapy and stable, and not before 37 weeks if antihypertensive therapy and stable.

The upper limit of 39 6/7 weeks is challenged, however, because data support that induction of labor at either 38 or 39 weeks reduces the risk of severe hypertensive complications (such as superimposed preeclampsia and eclampsia) without increasing the risk of cesarean delivery. Therefore, for patients with chronic hypertension, expectant management beyond 39 weeks is cautioned, to be done only with careful consideration of risks and with close surveillance.

As with ACOG’s original Task Force document on hypertension, clinicians should thoroughly read these 2 Practice Bulletins on hypertension in pregnancy as there are subtle changes that affect day-to-day practice, such as the definition of hypertension prior to pregnancy, treatment guidelines, and delivery timing recommendations. As always, these are guidelines, and the obstetrician’s clinical judgment and the needs of specific patient populations also must be taken into account.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:964-973.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- ACOG Practice Advisory. Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin’s role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM Statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://www.smfm.org/publications/280-smfm-statement-use-of-17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone-caproate-for-prevention-of-recurrent-preterm-birth. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, October 29, 2019. Advisory Committee Briefing Materials: Available for Public Release. https://www.fda.gov/media/132004/download. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. SMFM responds to the FDA’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Advisory Committee. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2091/17P_Public_Statement.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; November 2013.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-e50.

Attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and often quoted in contemporary times, is the expression “the only constant is change.” This sentiment rings true for the field of obstetrics this past year, as several bread-and-butter guidelines for managing common obstetric conditions were either challenged or altered.

The publication of the PROLONG trial called into question the use of intramuscular progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth. Prophylaxis guidelines for group B streptococcal disease were updated, including several significant clinical practice changes. Finally, there was a comprehensive overhaul of the guidelines for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which replaced a landmark Task Force document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that was published only a few years ago.

Change is constant, and in obstetrics it is vital to keep up with the changing guidelines that result as new data become available for digestion and implementation into everyday clinical practice.

Results from the PROLONG trial may shake up treatment options for recurrent preterm birth

Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

The drug 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC, or 17P; Makena) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB) in women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of singleton spontaneous PTB. The results of the trial by Meis and colleagues of 17-OHPC played a major role in achieving that approval, as it demonstrated a 34% reduction in recurrent PTB and a reduction in some neonatal morbidities.1 Following the drug's approval, both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) published guidelines recommending progesterone therapy, including 17-OHPC, for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous PTB.2

The FDA approval of 17-OHPC was granted under an accelerated conditional pathway that required a confirmatory trial evaluating efficacy, safety, and long-term infant follow-up to be performed by the sponsor. That trial, Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation (PROLONG), was started in 2009, and its results were published on October 25, 2019.3

Continue to: Design of the trial...

Design of the trial

PROLONG was a multicenter (93 sites), randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 9 countries (23% of participants were in the United States, 60% were in Russia and Ukraine). The co-primary outcome was PTB < 35 weeks and a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality index. The primary safety outcome was fetal/early infant death.

The study was designed to have 98% power to detect a 30% reduction in PTB < 35 weeks, and 90% power to detect a 35% reduction in the neonatal composite index. It included 1,708 participants (1,130 were treated with 17-OHPC, and 578 received placebo).

Trial outcomes. There was no difference in PTB < 35 weeks between the 17-OHPC and the placebo groups (11.0% vs 11.5%; relative risk [RR], 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71-1.26). There was no difference in PTB < 32 or < 37 weeks.

The study revealed also that there was no difference between groups in the neonatal composite index (5.6% for 17-OHPC vs 5.0% for placebo; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). In addition, there was no difference in fetal/early infant death between the 17-OHPC and placebo groups (1.7% vs 1.9%; RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.4-1.81).

Conclusions. The trial investigators concluded that 17-OHPC did not demonstrate a reduction in recurrent PTB and did not decrease neonatal morbidity.

Study limitations included underpowering and selection bias

The investigators noted that the PTB rate in PROLONG was unexpectedly almost 50% lower than that in the Meis trial, and that therefore the PROLONG trial was underpowered to assess the primary outcomes.

Further, the study populations of the 2 trials were very different: The Meis trial included women at higher baseline risk for PTB (> 1 prior PTB and at least 1 other risk factor for PTB). Additionally, while the PROLONG trial included mostly white (90%), married (90%), nonsmoking women (8% smoked), the Meis trial population was 59% black and 50% married, and 20% were smokers.

The availability and common use of 17-OHPC in the United States likely led to a selection bias for the PROLONG trial population, as the highest-risk patients were most likely already receiving treatment and were therefore excluded from the PROLONG trial.

Society, and FDA, responses to the new data

The results of the PROLONG trial call into question what has become standard practice for patients with a history of spontaneous PTB in the United States. While the safety profile of 17-OHPC has not been cited as a concern, whether or not the drug should be used at all has—as has its current FDA-approved status.

In response to the publication of the PROLONG trial results, ACOG released a Practice Advisory that acknowledged the study's findings but did not alter the current recommendations to continue to offer progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, upholding ACOG's current Practice Bulletin guidance.2,4 Additional considerations for offering 17-OHPC use include the patients' preferences, available resources, and the setting for the intervention.

SMFM's response was more specific, stating that it is reasonable to continue to use 17-OHPC in high-risk patient populations consistent with those in the Meis trial.5 In the rest of the general population at risk for recurrent PTB, SMFM recommends that, due to uncertain benefit with 17-OHPC, the high cost, patient discomfort, and increased visits should be taken into account.

Four days after the publication of the PROLONG study, the FDA Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17-OHPC.6 In response, SMFM released a statement supporting continued access to 17-OHPC.7 The FDA's final decision on the status of the drug is expected within the next several months from this writing.

17-OHPC continues to be considered safe and still is recommended by both ACOG and SMFM for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth in high-risk patients. The high-risk patient population who may benefit most from this therapy is still not certain, but hopefully future studies will better delineate this. The landscape for 17-OHPC use may change dramatically if FDA approval is not upheld in the future. In my current practice, I am continuing to offer 17-OHPC to patients per the current ACOG guidelines, but I am counseling patients in a shared decision-making model regarding the findings of the PROLONG trial and the potential change in FDA approval.

Continue to: ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease...

ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of newborn infection and is associated with maternal infections as well as preterm labor and stillbirth. Early-onset GBS disease occurs within 7 days of birth and is linked to vertical transmission via maternal colonization of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract and fetal/neonatal aspiration at birth.

Preventing early-onset GBS disease with maternal screening and intrapartum prophylaxis according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines has reduced early-onset disease by 80% since the 1990s. By contrast, late-onset GBS infection, which occurs 7 days to 3 months after birth, usually is associated with horizontal maternal transmission or hospital or community infections, and it is not prevented by intrapartum treatment.

In 2018, the CDC transferred responsibility for GBS prophylaxis guidelines to ACOG and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In July 2019, ACOG released its Committee Opinion on preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns.8 This guidance replaces and updates the previous guidelines, with 3 notable changes.

The screening timing has changed

In the CDC's 2010 guidelines, GBS screening was recommended to start at 35 weeks' gestation. The new guidelines recommend universal vaginal-rectal screening at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation. The new timing of culture will shift the expected 5-week window in which GBS cultures are considered valid up to at least 41 weeks' gestation. The rationale for this change is that any GBS-unknown patient who previously would have been cultured under 37 weeks' would be an automatic candidate for empiric therapy and the lower rate of birth in the 35th versus the 41st week of gestation.

Identifying candidates for intrapartum treatment

The usual indications for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis include a GBS-positive culture at 36 weeks or beyond, GBS bacteriuria at any point in pregnancy, a prior GBS-affected child, or unknown GBS status with any of the following: < 37 weeks, rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours or temperature ≥ 100.4°F (38°C), and a positive rapid GBS culture in labor. In addition, antibiotics now should be considered for patients at term with unknown GBS status but with a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

This represents a major practice change for women at ≥ 37 weeks with unknown GBS status and no other traditional risk factors. The rationale for this recommendation is that women who have been positive for GBS in a prior pregnancy have a 50% chance of being colonized in the current pregnancy, and their newborns are therefore at higher risk for early-onset GBS disease.

Managing patients with penicillin allergy

Intravenous penicillin (or ampicillin) remains the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis against GBS due to its efficacy and specific, narrow coverage of gram-positive organisms. The updated recommendations emphasize that it is important to carefully evaluate patients with reported penicillin allergies for several reasons: determining risk of anaphylaxis and clindamycin susceptibility testing in GBS evaluations are often overlooked by obstetric providers, the need for antibiotic stewardship to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance, and clarification of allergy status for future health care needs.

Three recommendations are made:

- Laboratory requisitions for cultures should specifically note a penicillin allergy so that clindamycin susceptibility testing can be performed.

- Penicillin allergy skin testing should be considered for patients at unknown or low risk for anaphylaxis, as it is considered safe in pregnancy and most patients (80%-90%) who report a penicillin allergy are actually penicillin tolerant.

- For patients at high risk for anaphylaxis to penicillin, the recommended vancomycin dosing has been changed from 1 g IV every 12 hours to 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g). Renal function should be assessed prior to dosing. This weight- and renal function-based dosing increased neonatal therapeutic levels in several studies of different doses.

ACOG's key recommendations for preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns include:

- Universal vaginal-rectal screening for GBS should be performed at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for low-risk patients at term with unknown GBS status and a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

- Patients with a reported penicillin allergy require careful evaluation of the nature of their allergy, including consideration of skin testing and GBS susceptibility evaluation in order to promote the best practices for antibiotic use.

- For GBS-positive patients at high risk for penicillin anaphylaxis, vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g) is recommended.

Continue to: Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations...

Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

In 2013, ACOG released "Hypertension in pregnancy," a 99-page comprehensive document developed by their Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy, to summarize knowledge on the subject, provide guidelines for management, and identify needed areas of research.9 I summarized key points from that document in the 2014 "Update on Obstetrics" (OBG Manag. 2013;26[1]:28-36). Now, ACOG has released 2 Practice Bulletins—"Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia" and "Chronic hypertension in pregnancy"—that replace the 2013 document.10,11 These Practice Bulletins are quite comprehensive and warrant a thorough read. Several noteworthy changes relevant to the practicing obstetrician are summarized below.

Highlights of revised guidance

Expectant management vs early delivery in preeclampsia with fetal growth restriction. Fetal growth restriction, which was removed from the definition of preeclampsia with severe features in 2013, is no longer an indication for delivery in preeclampsia with severe features (previously, if the estimated fetal weight was < 5th percentile for gestational age, delivery after steroid administration was recommended). Rather, expectant management is reasonable if fetal antenatal testing, amniotic fluid, and Doppler ultrasound studies are reassuring. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies continue to be an indication for earlier delivery.

Postpartum NSAID use in hypertension. The 2013 document cautioned against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use postpartum in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy because of concern for exacerbating hypertension. The updated Practice Bulletins recommend NSAIDs as the preferred choice over opioid analgesics as data have not shown these drugs to increase blood pressure, antihypertensive requirements, or other adverse events in postpartum patients with blood pressure issues.

More women will be diagnosed with chronic hypertension. Recently, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association changed the definition of hypertension. Stage 1 hypertension is now defined as a systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of 80-89 mm Hg. Treatment of stage 1 hypertension is recommended for nonpregnant adults with risk factors for current or future cardiovascular disease. The potential impact is that more women will enter pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, and more may be on prepregnancy antihypertensive therapy that will need to be addressed during the pregnancy.

Blood pressure goals. The target blood pressure range for pregnant women with chronic hypertension is recommended to be ≥ 120/80 mm Hg and < 160/110 mm Hg (this represents a slight change, as previously diastolic blood pressure was to be < 105 mm Hg). Postpartum blood pressure goals of < 150/100 mm Hg remain the same.

Managing acute hypertensive emergencies. Both Practice Bulletins emphasize the importance of aggressive management of acute hypertensive emergency, with options for 3 protocols: labetalol, nifedipine, and hydralazine. The goal is to administer antihypertensive therapy within 30 to 60 minutes, but administration as soon as feasibly possible after diagnosis of severe hypertension is ideal.

Timing of delivery. Recommended delivery timing in patients with chronic hypertension was slightly altered (previous recommendations included a range of 37 to 39 6/7 weeks). The lower limit of gestational age for recommended delivery timing in chronic hypertension has not changed—it remains not before 38 weeks if no antihypertensive therapy and stable, and not before 37 weeks if antihypertensive therapy and stable.

The upper limit of 39 6/7 weeks is challenged, however, because data support that induction of labor at either 38 or 39 weeks reduces the risk of severe hypertensive complications (such as superimposed preeclampsia and eclampsia) without increasing the risk of cesarean delivery. Therefore, for patients with chronic hypertension, expectant management beyond 39 weeks is cautioned, to be done only with careful consideration of risks and with close surveillance.

As with ACOG’s original Task Force document on hypertension, clinicians should thoroughly read these 2 Practice Bulletins on hypertension in pregnancy as there are subtle changes that affect day-to-day practice, such as the definition of hypertension prior to pregnancy, treatment guidelines, and delivery timing recommendations. As always, these are guidelines, and the obstetrician’s clinical judgment and the needs of specific patient populations also must be taken into account.

Attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, and often quoted in contemporary times, is the expression “the only constant is change.” This sentiment rings true for the field of obstetrics this past year, as several bread-and-butter guidelines for managing common obstetric conditions were either challenged or altered.

The publication of the PROLONG trial called into question the use of intramuscular progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth. Prophylaxis guidelines for group B streptococcal disease were updated, including several significant clinical practice changes. Finally, there was a comprehensive overhaul of the guidelines for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, which replaced a landmark Task Force document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that was published only a few years ago.

Change is constant, and in obstetrics it is vital to keep up with the changing guidelines that result as new data become available for digestion and implementation into everyday clinical practice.

Results from the PROLONG trial may shake up treatment options for recurrent preterm birth

Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

The drug 17 α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate (17-OHPC, or 17P; Makena) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth (PTB) in women with a singleton pregnancy and a history of singleton spontaneous PTB. The results of the trial by Meis and colleagues of 17-OHPC played a major role in achieving that approval, as it demonstrated a 34% reduction in recurrent PTB and a reduction in some neonatal morbidities.1 Following the drug's approval, both ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) published guidelines recommending progesterone therapy, including 17-OHPC, for the prevention of recurrent spontaneous PTB.2

The FDA approval of 17-OHPC was granted under an accelerated conditional pathway that required a confirmatory trial evaluating efficacy, safety, and long-term infant follow-up to be performed by the sponsor. That trial, Progestin's Role in Optimizing Neonatal Gestation (PROLONG), was started in 2009, and its results were published on October 25, 2019.3

Continue to: Design of the trial...

Design of the trial

PROLONG was a multicenter (93 sites), randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study conducted in 9 countries (23% of participants were in the United States, 60% were in Russia and Ukraine). The co-primary outcome was PTB < 35 weeks and a composite neonatal morbidity and mortality index. The primary safety outcome was fetal/early infant death.

The study was designed to have 98% power to detect a 30% reduction in PTB < 35 weeks, and 90% power to detect a 35% reduction in the neonatal composite index. It included 1,708 participants (1,130 were treated with 17-OHPC, and 578 received placebo).

Trial outcomes. There was no difference in PTB < 35 weeks between the 17-OHPC and the placebo groups (11.0% vs 11.5%; relative risk [RR], 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71-1.26). There was no difference in PTB < 32 or < 37 weeks.

The study revealed also that there was no difference between groups in the neonatal composite index (5.6% for 17-OHPC vs 5.0% for placebo; RR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.68-1.61). In addition, there was no difference in fetal/early infant death between the 17-OHPC and placebo groups (1.7% vs 1.9%; RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.4-1.81).

Conclusions. The trial investigators concluded that 17-OHPC did not demonstrate a reduction in recurrent PTB and did not decrease neonatal morbidity.

Study limitations included underpowering and selection bias

The investigators noted that the PTB rate in PROLONG was unexpectedly almost 50% lower than that in the Meis trial, and that therefore the PROLONG trial was underpowered to assess the primary outcomes.

Further, the study populations of the 2 trials were very different: The Meis trial included women at higher baseline risk for PTB (> 1 prior PTB and at least 1 other risk factor for PTB). Additionally, while the PROLONG trial included mostly white (90%), married (90%), nonsmoking women (8% smoked), the Meis trial population was 59% black and 50% married, and 20% were smokers.

The availability and common use of 17-OHPC in the United States likely led to a selection bias for the PROLONG trial population, as the highest-risk patients were most likely already receiving treatment and were therefore excluded from the PROLONG trial.

Society, and FDA, responses to the new data

The results of the PROLONG trial call into question what has become standard practice for patients with a history of spontaneous PTB in the United States. While the safety profile of 17-OHPC has not been cited as a concern, whether or not the drug should be used at all has—as has its current FDA-approved status.

In response to the publication of the PROLONG trial results, ACOG released a Practice Advisory that acknowledged the study's findings but did not alter the current recommendations to continue to offer progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth, upholding ACOG's current Practice Bulletin guidance.2,4 Additional considerations for offering 17-OHPC use include the patients' preferences, available resources, and the setting for the intervention.

SMFM's response was more specific, stating that it is reasonable to continue to use 17-OHPC in high-risk patient populations consistent with those in the Meis trial.5 In the rest of the general population at risk for recurrent PTB, SMFM recommends that, due to uncertain benefit with 17-OHPC, the high cost, patient discomfort, and increased visits should be taken into account.

Four days after the publication of the PROLONG study, the FDA Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee voted 9-7 to withdraw approval for 17-OHPC.6 In response, SMFM released a statement supporting continued access to 17-OHPC.7 The FDA's final decision on the status of the drug is expected within the next several months from this writing.

17-OHPC continues to be considered safe and still is recommended by both ACOG and SMFM for the prevention of recurrent preterm birth in high-risk patients. The high-risk patient population who may benefit most from this therapy is still not certain, but hopefully future studies will better delineate this. The landscape for 17-OHPC use may change dramatically if FDA approval is not upheld in the future. In my current practice, I am continuing to offer 17-OHPC to patients per the current ACOG guidelines, but I am counseling patients in a shared decision-making model regarding the findings of the PROLONG trial and the potential change in FDA approval.

Continue to: ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease...

ACOG updates guidance on preventing early-onset GBS disease

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

Group B streptococcus (GBS) is the leading cause of newborn infection and is associated with maternal infections as well as preterm labor and stillbirth. Early-onset GBS disease occurs within 7 days of birth and is linked to vertical transmission via maternal colonization of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract and fetal/neonatal aspiration at birth.

Preventing early-onset GBS disease with maternal screening and intrapartum prophylaxis according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines has reduced early-onset disease by 80% since the 1990s. By contrast, late-onset GBS infection, which occurs 7 days to 3 months after birth, usually is associated with horizontal maternal transmission or hospital or community infections, and it is not prevented by intrapartum treatment.

In 2018, the CDC transferred responsibility for GBS prophylaxis guidelines to ACOG and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In July 2019, ACOG released its Committee Opinion on preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns.8 This guidance replaces and updates the previous guidelines, with 3 notable changes.

The screening timing has changed

In the CDC's 2010 guidelines, GBS screening was recommended to start at 35 weeks' gestation. The new guidelines recommend universal vaginal-rectal screening at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation. The new timing of culture will shift the expected 5-week window in which GBS cultures are considered valid up to at least 41 weeks' gestation. The rationale for this change is that any GBS-unknown patient who previously would have been cultured under 37 weeks' would be an automatic candidate for empiric therapy and the lower rate of birth in the 35th versus the 41st week of gestation.

Identifying candidates for intrapartum treatment

The usual indications for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis include a GBS-positive culture at 36 weeks or beyond, GBS bacteriuria at any point in pregnancy, a prior GBS-affected child, or unknown GBS status with any of the following: < 37 weeks, rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours or temperature ≥ 100.4°F (38°C), and a positive rapid GBS culture in labor. In addition, antibiotics now should be considered for patients at term with unknown GBS status but with a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

This represents a major practice change for women at ≥ 37 weeks with unknown GBS status and no other traditional risk factors. The rationale for this recommendation is that women who have been positive for GBS in a prior pregnancy have a 50% chance of being colonized in the current pregnancy, and their newborns are therefore at higher risk for early-onset GBS disease.

Managing patients with penicillin allergy

Intravenous penicillin (or ampicillin) remains the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis against GBS due to its efficacy and specific, narrow coverage of gram-positive organisms. The updated recommendations emphasize that it is important to carefully evaluate patients with reported penicillin allergies for several reasons: determining risk of anaphylaxis and clindamycin susceptibility testing in GBS evaluations are often overlooked by obstetric providers, the need for antibiotic stewardship to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance, and clarification of allergy status for future health care needs.

Three recommendations are made:

- Laboratory requisitions for cultures should specifically note a penicillin allergy so that clindamycin susceptibility testing can be performed.

- Penicillin allergy skin testing should be considered for patients at unknown or low risk for anaphylaxis, as it is considered safe in pregnancy and most patients (80%-90%) who report a penicillin allergy are actually penicillin tolerant.

- For patients at high risk for anaphylaxis to penicillin, the recommended vancomycin dosing has been changed from 1 g IV every 12 hours to 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g). Renal function should be assessed prior to dosing. This weight- and renal function-based dosing increased neonatal therapeutic levels in several studies of different doses.

ACOG's key recommendations for preventing early-onset GBS disease in newborns include:

- Universal vaginal-rectal screening for GBS should be performed at 36 to 37 6/7 weeks' gestation.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for low-risk patients at term with unknown GBS status and a history of GBS colonization in a prior pregnancy.

- Patients with a reported penicillin allergy require careful evaluation of the nature of their allergy, including consideration of skin testing and GBS susceptibility evaluation in order to promote the best practices for antibiotic use.

- For GBS-positive patients at high risk for penicillin anaphylaxis, vancomycin 20 mg/kg IV every 8 hours (maximum single dose, 2 g) is recommended.

Continue to: Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations...

Managing hypertension in pregnancy: New recommendations

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

In 2013, ACOG released "Hypertension in pregnancy," a 99-page comprehensive document developed by their Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy, to summarize knowledge on the subject, provide guidelines for management, and identify needed areas of research.9 I summarized key points from that document in the 2014 "Update on Obstetrics" (OBG Manag. 2013;26[1]:28-36). Now, ACOG has released 2 Practice Bulletins—"Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia" and "Chronic hypertension in pregnancy"—that replace the 2013 document.10,11 These Practice Bulletins are quite comprehensive and warrant a thorough read. Several noteworthy changes relevant to the practicing obstetrician are summarized below.

Highlights of revised guidance

Expectant management vs early delivery in preeclampsia with fetal growth restriction. Fetal growth restriction, which was removed from the definition of preeclampsia with severe features in 2013, is no longer an indication for delivery in preeclampsia with severe features (previously, if the estimated fetal weight was < 5th percentile for gestational age, delivery after steroid administration was recommended). Rather, expectant management is reasonable if fetal antenatal testing, amniotic fluid, and Doppler ultrasound studies are reassuring. Abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies continue to be an indication for earlier delivery.

Postpartum NSAID use in hypertension. The 2013 document cautioned against nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use postpartum in women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy because of concern for exacerbating hypertension. The updated Practice Bulletins recommend NSAIDs as the preferred choice over opioid analgesics as data have not shown these drugs to increase blood pressure, antihypertensive requirements, or other adverse events in postpartum patients with blood pressure issues.

More women will be diagnosed with chronic hypertension. Recently, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association changed the definition of hypertension. Stage 1 hypertension is now defined as a systolic blood pressure of 130-139 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of 80-89 mm Hg. Treatment of stage 1 hypertension is recommended for nonpregnant adults with risk factors for current or future cardiovascular disease. The potential impact is that more women will enter pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, and more may be on prepregnancy antihypertensive therapy that will need to be addressed during the pregnancy.

Blood pressure goals. The target blood pressure range for pregnant women with chronic hypertension is recommended to be ≥ 120/80 mm Hg and < 160/110 mm Hg (this represents a slight change, as previously diastolic blood pressure was to be < 105 mm Hg). Postpartum blood pressure goals of < 150/100 mm Hg remain the same.

Managing acute hypertensive emergencies. Both Practice Bulletins emphasize the importance of aggressive management of acute hypertensive emergency, with options for 3 protocols: labetalol, nifedipine, and hydralazine. The goal is to administer antihypertensive therapy within 30 to 60 minutes, but administration as soon as feasibly possible after diagnosis of severe hypertension is ideal.

Timing of delivery. Recommended delivery timing in patients with chronic hypertension was slightly altered (previous recommendations included a range of 37 to 39 6/7 weeks). The lower limit of gestational age for recommended delivery timing in chronic hypertension has not changed—it remains not before 38 weeks if no antihypertensive therapy and stable, and not before 37 weeks if antihypertensive therapy and stable.

The upper limit of 39 6/7 weeks is challenged, however, because data support that induction of labor at either 38 or 39 weeks reduces the risk of severe hypertensive complications (such as superimposed preeclampsia and eclampsia) without increasing the risk of cesarean delivery. Therefore, for patients with chronic hypertension, expectant management beyond 39 weeks is cautioned, to be done only with careful consideration of risks and with close surveillance.

As with ACOG’s original Task Force document on hypertension, clinicians should thoroughly read these 2 Practice Bulletins on hypertension in pregnancy as there are subtle changes that affect day-to-day practice, such as the definition of hypertension prior to pregnancy, treatment guidelines, and delivery timing recommendations. As always, these are guidelines, and the obstetrician’s clinical judgment and the needs of specific patient populations also must be taken into account.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:964-973.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- ACOG Practice Advisory. Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin’s role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM Statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://www.smfm.org/publications/280-smfm-statement-use-of-17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone-caproate-for-prevention-of-recurrent-preterm-birth. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, October 29, 2019. Advisory Committee Briefing Materials: Available for Public Release. https://www.fda.gov/media/132004/download. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. SMFM responds to the FDA’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Advisory Committee. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2091/17P_Public_Statement.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; November 2013.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-e50.

- Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379-2385.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice bulletin No. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:964-973.

- Blackwell SC, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Biggio JR Jr, et al. 17-OHPC to prevent recurrent preterm birth in singleton gestations (PROLONG study): a multicenter, international, randomized double-blind trial. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-3400227.

- ACOG Practice Advisory. Clinical guidance for integration of the findings of the PROLONG study: progestin’s role in optimizing neonatal gestation. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Clinical-guidance-for-integration-of-the-findings-of-The-PROLONG-study-Progestins-Role-in-Optimizing. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Publications Committee. SMFM Statement: use of 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent preterm birth. https://www.smfm.org/publications/280-smfm-statement-use-of-17-alpha-hydroxyprogesterone-caproate-for-prevention-of-recurrent-preterm-birth. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Bone, Reproductive, and Urologic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting, October 29, 2019. Advisory Committee Briefing Materials: Available for Public Release. https://www.fda.gov/media/132004/download. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. SMFM responds to the FDA’s Bone, Reproductive and Urologic Advisory Committee. https://s3.amazonaws.com/cdn.smfm.org/media/2091/17P_Public_Statement.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2019.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists—Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion no. 782: prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e19-e40.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; November 2013.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 202: gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e1-e25.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 203: chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e26-e50.