User login

A treatment strategy that incorporates both water restrictions and sodium supplementation may be appropriate when differentiating between diagnoses of renal salt wasting syndrome and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Cisplatin is a potent antineoplastic agent derived from platinum and commonly used in the treatment of head and neck, bladder, ovarian, and testicular malignancies.1,2 Approximately 20% of all cancer patients are prescribed platinum-based chemotherapeutics.3 Although considered highly effective, cisplatin is also a dose-dependent nephrotoxin, inducing apoptosis in the proximal tubules of the nephron and reducing glomerular filtration rate. This nephron injury leads to inflammation and reduced medullary blood flow, causing further ischemic damage to the tubular cells.4 Given that the proximal tubule reabsorbs 67% of all sodium, cisplatin-induced nephron injuries can also lead to hyponatremia.5

The primary mechanisms of hyponatremia following cisplatin chemotherapy are syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and renal salt wasting syndrome (RSWS). Though these diagnoses have similar presentations, the treatment recommendations are different due to pathophysiologic differences. Fluid restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment, while increased sodium intake remains the hallmark of RSWS treatment.6 This patient presented with a combination of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) and hyponatremia secondary to RSWS. While RSWS and AKI are known complications of cisplatin chemotherapy, the combination is underreported in the literature. Therefore, this case report highlights the combination of these cisplatin-induced complications, emphasizes the clinical challenges in differentiating SIADH from RSWS, especially in the presence of a concomitant AKI, and suggests a treatment approach during diagnostic uncertainty.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the left neck on cycle 1, day 8 of cisplatin-based chemotherapy and ongoing radiation therapy (720 cGy of 6300 cGy), lung adenocarcinoma status postresection, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department (ED) at the request of his oncologist for abnormal laboratory values. In the ED, his metabolic panel showed a 131-mmol/L serum sodium, 3.3 mmol/L potassium, 83 mmol/L chloride, 29 mmol/L bicarbonate, 61 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and 8.8 mg/dL creatinine (baseline, 0.9 mg/dL). The patient reported throbbing headaches, persistent nausea, and multiple episodes of nonbloody emesis for several days that he attributed to his chemotherapy. He noted decreased urination without discomfort or changes in color or odor and no fatigue, fevers, chills, hematuria, flank, abdominal pain, thirst, or polydipsia. He reported no toxic ingestions or IV drug use. The patient had no relevant family history or additional social history. His outpatient medications included 10 mg cetirizine, 8 mg ondansetron, and 81 mg aspirin. On initial examination, his 137/66 mm Hg blood pressure was mildly elevated. The physical examination findings were notable for a 5-cm mass in the left neck that was firm and irregularly-shaped. His physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. He was admitted to the inpatient medicine service for an AKI complicated by symptomatic hyponatremia.

Investigations

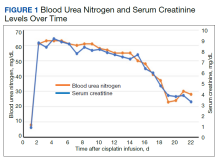

We evaluated the patient’s AKI based on treatment responsiveness, imaging, and laboratory testing. Renal and bladder ultrasound showed no evidence of hydronephrosis or obstruction. He had a benign urinalysis with microscopy absent for protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and cellular casts. His urine pH was 5.5 (reference range, 5.0-9.0) and specific gravity was 1.011 (reference range, 1.005-1.030). His urine electrolytes revealed 45-mmol/L urine sodium (reference range, 40-220), 33-mmol/L urine chloride (reference range, 110-250), 10-mmol/L urine potassium (reference range, 25-120), 106.7-mg/dL urine creatinine (reference range, 10-400) and a calculated 2.7% fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) and 22.0-mEq/L elevated urine anion gap. As a fluid challenge, he was treated with IV 0.9% sodium chloride at 100-125 mL/h, receiving 3 liters over the first 48 hours of his hospitalization. His creatinine peaked at 9.2 mg/dL and stabilized before improving later in his hospitalization (Figure 1). The patient initially had oliguria (< 0.5 mL/kg/h), which slowly improved over his hospital course. Unfortunately, due to multiple system and clinical factors, accurate inputs and outputs were not adequately maintained during his hospitalization.

We evaluated hyponatremia with a combination of serum and urine laboratory tests. In addition to urine electrolytes, the initial evaluation focused on trending his clinical trajectory. We repeated a basic metabolic panel every 4 to 6 hours. He had 278-mOsm/kg serum osmolality (reference range, 285-295) with an effective 217-mOsm/kg serum tonicity. His urine osmolality was 270.5 mOsm/kg.

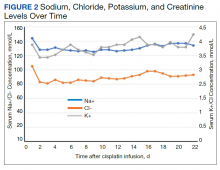

Despite administering 462 mEq sodium via crystalloid, his sodium worsened over the first 48 hours, reaching a nadir at 125 mmol/L on hospital day 3 (Figure 2). While he continued to appear euvolemic on physical examination, his blood pressure became difficult to control with 160- to 180-mm Hg systolic blood pressure readings. His thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was normal and aldosterone was low (4 ng/dL). Additional urine studies, including a 24-hour urine sample, were collected for further evaluation. His urine uric acid was 140 mg/d (reference range, 120-820); his serum uric acid level was 8.2 mg/dL (reference range, 3.0-9.0). His 24-hour urine creatinine was 0.57 g/d (reference range, 0.50-2.15) and uric acid to creatinine ratio was 246 mg/g (reference range, 60-580). His serum creatinine collected from the same day as his 24-hour urine sample was 7.3 mg/dL. His fractional excretion of uric acid (FEurate) was 21.9%.

Differential Diagnosis

The patient’s recent administration of cisplatin raised clinical suspicion of cisplatin-induced AKI. To avoid premature diagnostic closure, we used a systematic approach for thinking about our patient’s AKI, considering prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal etiologies. The unremarkable renal and bladder ultrasound made a postrenal etiology unlikely. The patient’s 2.7% FENa in the absence of a diuretic, limited responsiveness to crystalloid fluid resuscitation, 7.5 serum BUN/creatinine ratio, and 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality suggested an intrarenal etiology, which can be further divided into problems with glomeruli, tubules, small vessels, or interstitial space. The patient’s normal urinary microscopy with no evidence of protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, or cellular casts made a glomerular etiology less likely. The acute onset and lack of additional systemic features, other than hypertension, made a vascular etiology less likely. A tubular etiology, such as acute tubular necrosis (ATN), was highest on the differential and was followed by an interstitial etiology, such as acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).

Patients with drug-induced AIN commonly present with signs and symptoms of an allergic-type reaction, including fever, rash, hematuria, pyuria, and costovertebral angle tenderness. The patient lacked these symptoms. However, cisplatin is known to cause ATN in up to 20-30% of patients.7 Therefore, despite the lack of the classic muddy-brown, granular casts on urine microscopy, cisplatin-induced ATN remained the most likely etiology of his AKI. Moreover, ATN can cause hyponatremia. ATN is characterized by 3 phases: initiation, maintenance, and recovery phases.8 Hyponatremia occurs during the recovery phase, typically starting weeks after renal insult and associated with high urine output and diuresis. This patient presented 1 week after injury and had persistent oliguria, making ATN an unlikely culprit of his hyponatremia.

Our patient presented with hypotonic hyponatremia with a 131 mmol/L initial sodium level and an < 280 mOsm/kg effective serum osmolality, or serum tonicity. The serum tonicity is equivalent to the difference between the measured serum osmolality and the BUN. In the setting of profound AKI, this adjustment is essential for correctly categorizing a patient’s hyponatremia as hyper-, iso-, or hypotonic. The differential diagnosis for this patient’s hypotonic hyponatremia included dilutional effects of hypervolemia, SIADH, hyperthyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and RSWS. The patient’s volume examination, lack of predisposing comorbidities or suggestive biomarkers, and > 20 mmol/L urinary sodium made hypervolemia unlikely. His urinary osmolality and specific gravity made primary polydipsia unlikely. We worked up his hyponatremia according to a diagnostic algorithm (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0198).

The patient had a 217 mOsm/kg serum tonicity and a 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality, consistent with impaired water excretion. His presentation, TSH, and concordant decrease in sodium and potassium made an endocrine etiology of his hyponatremia less likely. In hindsight, a serum cortisol would have been beneficial to more completely exclude adrenal insufficiency. His urine sodium was elevated at 45 mmol/L, raising concern for RSWS or SIADH. The FEurate helped to distinguish between SIADH and RSWS. While FEurate is often elevated in both SIADH and RSWS initially, the FEurate normalizes in SIADH with normalization of the serum sodium. The ideal cutoff for posthyponatremia correction FEurate is debated; however, a FEurate value after sodium correction < 11% suggests SIADH while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.9 Our patient’s FEurate following the sodium correction (serum sodium 134 mmol/L) was 21.9%, most suggestive of RSWS.

Treatment

Upon admission, initial treatment focused on resolving the patient’s AKI. The oncology team discontinued the cisplatin-based chemotherapy. His medication dosages were adjusted for his renal function and additional nephrotoxins avoided. In consultation, the nephrology service recommended 100 mL/h fluid resuscitation. After the patient received 3 L of 0.9% sodium chloride, his creatinine showed limited improvement and his sodium worsened, trending from 131 mmol/L to a nadir of 125 mmol/L. We initiated oral free-water restriction while continuing IV infusion of 0.9% sodium chloride at 125 mL/h.

We further augmented his sodium intake with 1-g sodium chloride tablets with each meal. By hospital day 6, the patient’s serum sodium, BUN, and creatinine improved to 130 mEq/L, 50 mg/dL, and 7.7 mg/dL, respectively. We then discontinued the oral sodium chloride tablets, fluid restriction, and IV fluids in a stepwise fashion prior to discharge. At discharge, the patient’s serum sodium was 136 mEq/L and creatinine, 4.8 mg/dL. The patient’s clinical course was complicated by symptomatic hypertension with systolic blood pressures about 180 mm Hg, requiring intermittent IV hydralazine, which was transitioned to daily nifedipine. Concerned that fluid resuscitation contributed to his hypertension, the patient also received several doses of furosemide. At time of discharge, the patient remained hypertensive and was discharged with nifedipine 90 mg daily.

Outcome and Follow-up

The patient has remained stable clinically since discharge. One week after discharge, his serum sodium and creatinine were 138 mmol/L and 3.8 mg/dL, respectively. More than 1 month after discharge, his sodium remains in the reference range and his creatinine was stable at about 3.5 mg/dL. He continues to follow-up with nephrology, oncology, and radiation oncology. He has restarted chemotherapy with a carboplatin-based regimen without recurrence of hyponatremia or AKI. His blood pressure has gradually improved to the point where he no longer requires nifedipine.

Discussion

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved the use of cisplatin, an alkylating agent that inhibits DNA replication, in 1978 for the treatment of testicular cancer.10 Since its approval, cisplatin has increased in popularity and is now considered one of the most effective antineoplastic agents for the treatment of solid tumors.1 Unfortunately, cisplatin has a well-documented adverse effect profile that includes neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, nephrotoxicity, and ototoxicity.4 Despite frequent nephrotoxicity, cisplatin only occasionally causes hyponatremia and rarely causes RSWS, a known but potentially fatal complication. Moreover, the combination of AKI and RSWS is unique. Our patient presented with the unique combination of AKI and hyponatremia, most consistent with RSWS, likely precipitated from cisplatin chemotherapy. Through this case, we review cisplatin-associated electrolyte abnormalities, highlight the challenge of differentiating SIADH and RSWS, and suggest a treatment approach for hyponatremia during the period of diagnostic uncertainty.

Blachley and colleagues first discussed renal and electrolyte disturbances, specifically magnesium wasting, secondary to cisplatin use in 1981. In 1984, Kurtzberg and colleagues noted salt wasting in 2 patients receiving cisplatin therapy. The authors suggested that cisplatin inhibits solute transport in the thick ascending limb, causing clinically significant electrolyte abnormalities, coining the term cisplatin-induced salt wasting.11

The prevalence of cisplatin-induced salt wasting is unclear and likely underreported. In 1988, Hutchinson and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study and noted 10% of patients (n = 70) developed RSWS at some point over 18 months of cisplatin therapy—a higher rate than previously estimated.12 In 1992, another prospective cohort study evaluated the adverse effects of 47 patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin and reported hyponatremia in 43% of its 93 courses of chemotherapy. The authors did not report the etiology of these hyponatremia cases.13 Given the diagnostic challenge, RSWS may be underrepresented as a confirmed etiology of hyponatremia in cisplatin treatment.

Hyponatremia from cisplatin may present as either SIADH or RSWS, complicating treatment decisions. Both conditions lead to hypotonic hyponatremia with urine osmolality > 100 mOSm/kg and urine sodium levels > 40 mmol/L. However, pathophysiology behind SIADH and RSWS is different. In RSWS, proximal tubule damage causes hyponatremia, decreasing sodium reabsorption, and leading to impaired concentration gradient in every segment of the nephron. As a result, RSWS can lead to profound hyponatremia. Treatment typically consists of increasing sodium intake to correct serum sodium with salt tablets and hypertonic sodium chloride while treating the underlying etiology, in our case removing the offending agent, and waiting for proximal tubule function to recover.6 On the other hand, in SIADH, elevated antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases water reabsorption in the collecting duct, which has no impact on concentration gradients of the other nephron segments.14 Free-water restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment. Severe SIADH may require sodium repletion and/or the initiation of vaptans, ADH antagonists that competitively inhibit V2 receptors in the collecting duct to prevent water reabsorption.15

Our patient had an uncertain etiology of his hyponatremia throughout most of his treatment course, complicating our treatment decision-making. Initially, his measured serum osmolality was 278 mOsm/kg; however, his effective tonicity was lower. His AKI elevated his BUN, which in turnrequired us to calculate his serum tonicity (217 mOsm/kg) that was consistent with hypotonic hyponatremia. His elevated urine osmolality and urine sodium levels made SIADH and RSWS the most likely etiologies of his hyponatremia. To confirm the etiology, we waited for correction of his serum sodium. Therefore, we treated him with a combination of sodium repletion with 0.9% sodium chloride (154 mEq/L), hypertonic relative to his serum sodium, sodium chloride tablets, and free-water restriction. In this approach, we attempted to harmonize the treatment strategies for both SIADH and RSWS and effectively corrected his serum sodium. We evaluated his response to our treatment with a basic metabolic panel every 6 to 8 hours. Had his serum sodium decreased < 120 mmol/L, we planned to transfer the patient to the intensive care unit for 3% sodium chloride and/or intensification of his fluid restriction. A significant worsening of his hyponatremia would have strongly suggested hyponatremia secondary to SIADH since isotonic saline can worsen hyponatremia due to increased free-water reabsorption in the collecting duct.16

To differentiate between SIADH and RSWS, we relied on the FEurate after sodium correction. Multiple case reports from Japan have characterized the distinction between the processes through FEurate and serum uric acid. While the optimal cut-off values for FEurate require additional investigation, values < 11% after serum sodium correction suggests SIADH, while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.17 Prior cases have also emphasized serum hypouricemia as a distinguishing characteristic in RSWS. However, our case illustrates that serum hypouricemia is less reliable in the setting of AKI. Due to his severe AKI, our patient could not efficiently clear uric acid, likely contributing to his hyperuricemia.

Ultimately, our patient had an FEurate > 20%, which was suggestive of RSWS. Nevertheless, we recognize limitations and confounders in our diagnosis and have reflected on our diagnostic and management choices. First, the sensitivity and specificity of postsodium correction FEurate is unknown. Tracking the change in FEurate with our interventions would have increased our diagnostic utility, as suggested by Maesaka and colleagues.14 Second, our patient’s serum sodium was still at the lower end of the reference range after treatment, which may decrease the specificity of FEurate. Third, a plasma ADH collected during the initial phase of symptomatic hyponatremia would have helped differentiate between SIADH and RSWS.

Other diagnostic tests that could have excluded alternative diagnoses with even greater certainty include plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone, B-type natriuretic peptide, renin, cortisol, and thyroid function tests. From a practical standpoint, these laboratory results (excluding thyroid function test and brain natriuretic peptide) would have taken several weeks to result at our institution, limiting their clinical utility. Similarly, FEurate also has limited clinical utility, requiring effective treatment as part of the diagnostic test. Therefore, we recommend focusing on optimal treatment for hyponatremia of uncertain etiology, especially where SIADH and RSWS are the leading diagnoses.

Conclusions

We described a rare case of concomitant cisplatin-induced severe AKI and RSWS. We have emphasized the diagnostic challenge of distinguishing between SIADH and RSWS, especially with concomitant AKI, and have acknowledged that optimal treatment relies on accurate differentiation. However, differentiation may not be clinically feasible. Therefore, we suggest a treatment strategy that incorporates both free-water restriction and sodium supplementation via IV and/or oral administration.

1. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364-378. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025

2. Holditch SJ, Brown CN, Lombardi AM, Nguyen KN, Edelstein CL. Recent advances in models, mechanisms, biomarkers, and interventions in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):3011. Published 2019 Jun 20. doi:10.3390/ijms20123011

3. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The “accidental” cure—platinum-based treatment for cancer: the discovery of cisplatin. Published May 30, 2014. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/cisplatin

4. Ozkok A, Edelstein CL. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:967826. doi:10.1155/2014/967826

5. Palmer LG, Schnermann J. Integrated control of Na transport along the nephron. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(4):676-687. doi:10.2215/CJN.12391213

6. Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315. doi:10.2215/CJN.02740608

7. Shirali AC, Perazella MA. Tubulointerstitial injury associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):56-63. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2013.06.010

8. Agrawal M, Swartz R. Acute renal failure [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician 2001 Feb 1;63(3):445]. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2077-2088.

9. Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

10. Monneret C. Platinum anticancer drugs. From serendipity to rational design. Ann Pharm Fr. 2011;69(6):286-295. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2011.10.001

11. Kurtzberg J, Dennis VW, Kinney TR. Cisplatinum-induced renal salt wasting. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1984;12(2):150-154. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950120219

12. Hutchison FN, Perez EA, Gandara DR, Lawrence HJ, Kaysen GA. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with cisplatin. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(1):21-25. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-21

13. Lee YK, Shin DM. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with high-dose cisplatin, etoposide, and mitomycin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 1992;7(2):118-121. doi:10.3904/kjim.1992.7.2.118

14. Maesaka JK, Imbriano L, Mattana J, Gallagher D, Bade N, Sharif S. Differentiating SIADH from cerebral/renal salt wasting: failure of the volume approach and need for a new approach to hyponatremia. J Clin Med. 2014;3(4):1373-1385. Published 2014 Dec 8. doi:10.3390/jcm3041373

15. Palmer BF. The role of v2 receptor antagonists in the treatment of hyponatremia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2013;11(1):1-8. doi:10.5049/EBP.2013.11.1.1

16. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-S21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001

17. Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Miyawaki N. High prevalence of renal salt wasting without cerebral disease as cause of hyponatremia in general medical wards. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(1):15-22. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.03.02

A treatment strategy that incorporates both water restrictions and sodium supplementation may be appropriate when differentiating between diagnoses of renal salt wasting syndrome and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

A treatment strategy that incorporates both water restrictions and sodium supplementation may be appropriate when differentiating between diagnoses of renal salt wasting syndrome and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Cisplatin is a potent antineoplastic agent derived from platinum and commonly used in the treatment of head and neck, bladder, ovarian, and testicular malignancies.1,2 Approximately 20% of all cancer patients are prescribed platinum-based chemotherapeutics.3 Although considered highly effective, cisplatin is also a dose-dependent nephrotoxin, inducing apoptosis in the proximal tubules of the nephron and reducing glomerular filtration rate. This nephron injury leads to inflammation and reduced medullary blood flow, causing further ischemic damage to the tubular cells.4 Given that the proximal tubule reabsorbs 67% of all sodium, cisplatin-induced nephron injuries can also lead to hyponatremia.5

The primary mechanisms of hyponatremia following cisplatin chemotherapy are syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and renal salt wasting syndrome (RSWS). Though these diagnoses have similar presentations, the treatment recommendations are different due to pathophysiologic differences. Fluid restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment, while increased sodium intake remains the hallmark of RSWS treatment.6 This patient presented with a combination of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) and hyponatremia secondary to RSWS. While RSWS and AKI are known complications of cisplatin chemotherapy, the combination is underreported in the literature. Therefore, this case report highlights the combination of these cisplatin-induced complications, emphasizes the clinical challenges in differentiating SIADH from RSWS, especially in the presence of a concomitant AKI, and suggests a treatment approach during diagnostic uncertainty.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the left neck on cycle 1, day 8 of cisplatin-based chemotherapy and ongoing radiation therapy (720 cGy of 6300 cGy), lung adenocarcinoma status postresection, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department (ED) at the request of his oncologist for abnormal laboratory values. In the ED, his metabolic panel showed a 131-mmol/L serum sodium, 3.3 mmol/L potassium, 83 mmol/L chloride, 29 mmol/L bicarbonate, 61 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and 8.8 mg/dL creatinine (baseline, 0.9 mg/dL). The patient reported throbbing headaches, persistent nausea, and multiple episodes of nonbloody emesis for several days that he attributed to his chemotherapy. He noted decreased urination without discomfort or changes in color or odor and no fatigue, fevers, chills, hematuria, flank, abdominal pain, thirst, or polydipsia. He reported no toxic ingestions or IV drug use. The patient had no relevant family history or additional social history. His outpatient medications included 10 mg cetirizine, 8 mg ondansetron, and 81 mg aspirin. On initial examination, his 137/66 mm Hg blood pressure was mildly elevated. The physical examination findings were notable for a 5-cm mass in the left neck that was firm and irregularly-shaped. His physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. He was admitted to the inpatient medicine service for an AKI complicated by symptomatic hyponatremia.

Investigations

We evaluated the patient’s AKI based on treatment responsiveness, imaging, and laboratory testing. Renal and bladder ultrasound showed no evidence of hydronephrosis or obstruction. He had a benign urinalysis with microscopy absent for protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and cellular casts. His urine pH was 5.5 (reference range, 5.0-9.0) and specific gravity was 1.011 (reference range, 1.005-1.030). His urine electrolytes revealed 45-mmol/L urine sodium (reference range, 40-220), 33-mmol/L urine chloride (reference range, 110-250), 10-mmol/L urine potassium (reference range, 25-120), 106.7-mg/dL urine creatinine (reference range, 10-400) and a calculated 2.7% fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) and 22.0-mEq/L elevated urine anion gap. As a fluid challenge, he was treated with IV 0.9% sodium chloride at 100-125 mL/h, receiving 3 liters over the first 48 hours of his hospitalization. His creatinine peaked at 9.2 mg/dL and stabilized before improving later in his hospitalization (Figure 1). The patient initially had oliguria (< 0.5 mL/kg/h), which slowly improved over his hospital course. Unfortunately, due to multiple system and clinical factors, accurate inputs and outputs were not adequately maintained during his hospitalization.

We evaluated hyponatremia with a combination of serum and urine laboratory tests. In addition to urine electrolytes, the initial evaluation focused on trending his clinical trajectory. We repeated a basic metabolic panel every 4 to 6 hours. He had 278-mOsm/kg serum osmolality (reference range, 285-295) with an effective 217-mOsm/kg serum tonicity. His urine osmolality was 270.5 mOsm/kg.

Despite administering 462 mEq sodium via crystalloid, his sodium worsened over the first 48 hours, reaching a nadir at 125 mmol/L on hospital day 3 (Figure 2). While he continued to appear euvolemic on physical examination, his blood pressure became difficult to control with 160- to 180-mm Hg systolic blood pressure readings. His thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was normal and aldosterone was low (4 ng/dL). Additional urine studies, including a 24-hour urine sample, were collected for further evaluation. His urine uric acid was 140 mg/d (reference range, 120-820); his serum uric acid level was 8.2 mg/dL (reference range, 3.0-9.0). His 24-hour urine creatinine was 0.57 g/d (reference range, 0.50-2.15) and uric acid to creatinine ratio was 246 mg/g (reference range, 60-580). His serum creatinine collected from the same day as his 24-hour urine sample was 7.3 mg/dL. His fractional excretion of uric acid (FEurate) was 21.9%.

Differential Diagnosis

The patient’s recent administration of cisplatin raised clinical suspicion of cisplatin-induced AKI. To avoid premature diagnostic closure, we used a systematic approach for thinking about our patient’s AKI, considering prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal etiologies. The unremarkable renal and bladder ultrasound made a postrenal etiology unlikely. The patient’s 2.7% FENa in the absence of a diuretic, limited responsiveness to crystalloid fluid resuscitation, 7.5 serum BUN/creatinine ratio, and 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality suggested an intrarenal etiology, which can be further divided into problems with glomeruli, tubules, small vessels, or interstitial space. The patient’s normal urinary microscopy with no evidence of protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, or cellular casts made a glomerular etiology less likely. The acute onset and lack of additional systemic features, other than hypertension, made a vascular etiology less likely. A tubular etiology, such as acute tubular necrosis (ATN), was highest on the differential and was followed by an interstitial etiology, such as acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).

Patients with drug-induced AIN commonly present with signs and symptoms of an allergic-type reaction, including fever, rash, hematuria, pyuria, and costovertebral angle tenderness. The patient lacked these symptoms. However, cisplatin is known to cause ATN in up to 20-30% of patients.7 Therefore, despite the lack of the classic muddy-brown, granular casts on urine microscopy, cisplatin-induced ATN remained the most likely etiology of his AKI. Moreover, ATN can cause hyponatremia. ATN is characterized by 3 phases: initiation, maintenance, and recovery phases.8 Hyponatremia occurs during the recovery phase, typically starting weeks after renal insult and associated with high urine output and diuresis. This patient presented 1 week after injury and had persistent oliguria, making ATN an unlikely culprit of his hyponatremia.

Our patient presented with hypotonic hyponatremia with a 131 mmol/L initial sodium level and an < 280 mOsm/kg effective serum osmolality, or serum tonicity. The serum tonicity is equivalent to the difference between the measured serum osmolality and the BUN. In the setting of profound AKI, this adjustment is essential for correctly categorizing a patient’s hyponatremia as hyper-, iso-, or hypotonic. The differential diagnosis for this patient’s hypotonic hyponatremia included dilutional effects of hypervolemia, SIADH, hyperthyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and RSWS. The patient’s volume examination, lack of predisposing comorbidities or suggestive biomarkers, and > 20 mmol/L urinary sodium made hypervolemia unlikely. His urinary osmolality and specific gravity made primary polydipsia unlikely. We worked up his hyponatremia according to a diagnostic algorithm (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0198).

The patient had a 217 mOsm/kg serum tonicity and a 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality, consistent with impaired water excretion. His presentation, TSH, and concordant decrease in sodium and potassium made an endocrine etiology of his hyponatremia less likely. In hindsight, a serum cortisol would have been beneficial to more completely exclude adrenal insufficiency. His urine sodium was elevated at 45 mmol/L, raising concern for RSWS or SIADH. The FEurate helped to distinguish between SIADH and RSWS. While FEurate is often elevated in both SIADH and RSWS initially, the FEurate normalizes in SIADH with normalization of the serum sodium. The ideal cutoff for posthyponatremia correction FEurate is debated; however, a FEurate value after sodium correction < 11% suggests SIADH while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.9 Our patient’s FEurate following the sodium correction (serum sodium 134 mmol/L) was 21.9%, most suggestive of RSWS.

Treatment

Upon admission, initial treatment focused on resolving the patient’s AKI. The oncology team discontinued the cisplatin-based chemotherapy. His medication dosages were adjusted for his renal function and additional nephrotoxins avoided. In consultation, the nephrology service recommended 100 mL/h fluid resuscitation. After the patient received 3 L of 0.9% sodium chloride, his creatinine showed limited improvement and his sodium worsened, trending from 131 mmol/L to a nadir of 125 mmol/L. We initiated oral free-water restriction while continuing IV infusion of 0.9% sodium chloride at 125 mL/h.

We further augmented his sodium intake with 1-g sodium chloride tablets with each meal. By hospital day 6, the patient’s serum sodium, BUN, and creatinine improved to 130 mEq/L, 50 mg/dL, and 7.7 mg/dL, respectively. We then discontinued the oral sodium chloride tablets, fluid restriction, and IV fluids in a stepwise fashion prior to discharge. At discharge, the patient’s serum sodium was 136 mEq/L and creatinine, 4.8 mg/dL. The patient’s clinical course was complicated by symptomatic hypertension with systolic blood pressures about 180 mm Hg, requiring intermittent IV hydralazine, which was transitioned to daily nifedipine. Concerned that fluid resuscitation contributed to his hypertension, the patient also received several doses of furosemide. At time of discharge, the patient remained hypertensive and was discharged with nifedipine 90 mg daily.

Outcome and Follow-up

The patient has remained stable clinically since discharge. One week after discharge, his serum sodium and creatinine were 138 mmol/L and 3.8 mg/dL, respectively. More than 1 month after discharge, his sodium remains in the reference range and his creatinine was stable at about 3.5 mg/dL. He continues to follow-up with nephrology, oncology, and radiation oncology. He has restarted chemotherapy with a carboplatin-based regimen without recurrence of hyponatremia or AKI. His blood pressure has gradually improved to the point where he no longer requires nifedipine.

Discussion

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved the use of cisplatin, an alkylating agent that inhibits DNA replication, in 1978 for the treatment of testicular cancer.10 Since its approval, cisplatin has increased in popularity and is now considered one of the most effective antineoplastic agents for the treatment of solid tumors.1 Unfortunately, cisplatin has a well-documented adverse effect profile that includes neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, nephrotoxicity, and ototoxicity.4 Despite frequent nephrotoxicity, cisplatin only occasionally causes hyponatremia and rarely causes RSWS, a known but potentially fatal complication. Moreover, the combination of AKI and RSWS is unique. Our patient presented with the unique combination of AKI and hyponatremia, most consistent with RSWS, likely precipitated from cisplatin chemotherapy. Through this case, we review cisplatin-associated electrolyte abnormalities, highlight the challenge of differentiating SIADH and RSWS, and suggest a treatment approach for hyponatremia during the period of diagnostic uncertainty.

Blachley and colleagues first discussed renal and electrolyte disturbances, specifically magnesium wasting, secondary to cisplatin use in 1981. In 1984, Kurtzberg and colleagues noted salt wasting in 2 patients receiving cisplatin therapy. The authors suggested that cisplatin inhibits solute transport in the thick ascending limb, causing clinically significant electrolyte abnormalities, coining the term cisplatin-induced salt wasting.11

The prevalence of cisplatin-induced salt wasting is unclear and likely underreported. In 1988, Hutchinson and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study and noted 10% of patients (n = 70) developed RSWS at some point over 18 months of cisplatin therapy—a higher rate than previously estimated.12 In 1992, another prospective cohort study evaluated the adverse effects of 47 patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin and reported hyponatremia in 43% of its 93 courses of chemotherapy. The authors did not report the etiology of these hyponatremia cases.13 Given the diagnostic challenge, RSWS may be underrepresented as a confirmed etiology of hyponatremia in cisplatin treatment.

Hyponatremia from cisplatin may present as either SIADH or RSWS, complicating treatment decisions. Both conditions lead to hypotonic hyponatremia with urine osmolality > 100 mOSm/kg and urine sodium levels > 40 mmol/L. However, pathophysiology behind SIADH and RSWS is different. In RSWS, proximal tubule damage causes hyponatremia, decreasing sodium reabsorption, and leading to impaired concentration gradient in every segment of the nephron. As a result, RSWS can lead to profound hyponatremia. Treatment typically consists of increasing sodium intake to correct serum sodium with salt tablets and hypertonic sodium chloride while treating the underlying etiology, in our case removing the offending agent, and waiting for proximal tubule function to recover.6 On the other hand, in SIADH, elevated antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases water reabsorption in the collecting duct, which has no impact on concentration gradients of the other nephron segments.14 Free-water restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment. Severe SIADH may require sodium repletion and/or the initiation of vaptans, ADH antagonists that competitively inhibit V2 receptors in the collecting duct to prevent water reabsorption.15

Our patient had an uncertain etiology of his hyponatremia throughout most of his treatment course, complicating our treatment decision-making. Initially, his measured serum osmolality was 278 mOsm/kg; however, his effective tonicity was lower. His AKI elevated his BUN, which in turnrequired us to calculate his serum tonicity (217 mOsm/kg) that was consistent with hypotonic hyponatremia. His elevated urine osmolality and urine sodium levels made SIADH and RSWS the most likely etiologies of his hyponatremia. To confirm the etiology, we waited for correction of his serum sodium. Therefore, we treated him with a combination of sodium repletion with 0.9% sodium chloride (154 mEq/L), hypertonic relative to his serum sodium, sodium chloride tablets, and free-water restriction. In this approach, we attempted to harmonize the treatment strategies for both SIADH and RSWS and effectively corrected his serum sodium. We evaluated his response to our treatment with a basic metabolic panel every 6 to 8 hours. Had his serum sodium decreased < 120 mmol/L, we planned to transfer the patient to the intensive care unit for 3% sodium chloride and/or intensification of his fluid restriction. A significant worsening of his hyponatremia would have strongly suggested hyponatremia secondary to SIADH since isotonic saline can worsen hyponatremia due to increased free-water reabsorption in the collecting duct.16

To differentiate between SIADH and RSWS, we relied on the FEurate after sodium correction. Multiple case reports from Japan have characterized the distinction between the processes through FEurate and serum uric acid. While the optimal cut-off values for FEurate require additional investigation, values < 11% after serum sodium correction suggests SIADH, while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.17 Prior cases have also emphasized serum hypouricemia as a distinguishing characteristic in RSWS. However, our case illustrates that serum hypouricemia is less reliable in the setting of AKI. Due to his severe AKI, our patient could not efficiently clear uric acid, likely contributing to his hyperuricemia.

Ultimately, our patient had an FEurate > 20%, which was suggestive of RSWS. Nevertheless, we recognize limitations and confounders in our diagnosis and have reflected on our diagnostic and management choices. First, the sensitivity and specificity of postsodium correction FEurate is unknown. Tracking the change in FEurate with our interventions would have increased our diagnostic utility, as suggested by Maesaka and colleagues.14 Second, our patient’s serum sodium was still at the lower end of the reference range after treatment, which may decrease the specificity of FEurate. Third, a plasma ADH collected during the initial phase of symptomatic hyponatremia would have helped differentiate between SIADH and RSWS.

Other diagnostic tests that could have excluded alternative diagnoses with even greater certainty include plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone, B-type natriuretic peptide, renin, cortisol, and thyroid function tests. From a practical standpoint, these laboratory results (excluding thyroid function test and brain natriuretic peptide) would have taken several weeks to result at our institution, limiting their clinical utility. Similarly, FEurate also has limited clinical utility, requiring effective treatment as part of the diagnostic test. Therefore, we recommend focusing on optimal treatment for hyponatremia of uncertain etiology, especially where SIADH and RSWS are the leading diagnoses.

Conclusions

We described a rare case of concomitant cisplatin-induced severe AKI and RSWS. We have emphasized the diagnostic challenge of distinguishing between SIADH and RSWS, especially with concomitant AKI, and have acknowledged that optimal treatment relies on accurate differentiation. However, differentiation may not be clinically feasible. Therefore, we suggest a treatment strategy that incorporates both free-water restriction and sodium supplementation via IV and/or oral administration.

Cisplatin is a potent antineoplastic agent derived from platinum and commonly used in the treatment of head and neck, bladder, ovarian, and testicular malignancies.1,2 Approximately 20% of all cancer patients are prescribed platinum-based chemotherapeutics.3 Although considered highly effective, cisplatin is also a dose-dependent nephrotoxin, inducing apoptosis in the proximal tubules of the nephron and reducing glomerular filtration rate. This nephron injury leads to inflammation and reduced medullary blood flow, causing further ischemic damage to the tubular cells.4 Given that the proximal tubule reabsorbs 67% of all sodium, cisplatin-induced nephron injuries can also lead to hyponatremia.5

The primary mechanisms of hyponatremia following cisplatin chemotherapy are syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) and renal salt wasting syndrome (RSWS). Though these diagnoses have similar presentations, the treatment recommendations are different due to pathophysiologic differences. Fluid restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment, while increased sodium intake remains the hallmark of RSWS treatment.6 This patient presented with a combination of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) and hyponatremia secondary to RSWS. While RSWS and AKI are known complications of cisplatin chemotherapy, the combination is underreported in the literature. Therefore, this case report highlights the combination of these cisplatin-induced complications, emphasizes the clinical challenges in differentiating SIADH from RSWS, especially in the presence of a concomitant AKI, and suggests a treatment approach during diagnostic uncertainty.

Case Presentation

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the left neck on cycle 1, day 8 of cisplatin-based chemotherapy and ongoing radiation therapy (720 cGy of 6300 cGy), lung adenocarcinoma status postresection, and hyperlipidemia presented to the emergency department (ED) at the request of his oncologist for abnormal laboratory values. In the ED, his metabolic panel showed a 131-mmol/L serum sodium, 3.3 mmol/L potassium, 83 mmol/L chloride, 29 mmol/L bicarbonate, 61 mg/dL blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and 8.8 mg/dL creatinine (baseline, 0.9 mg/dL). The patient reported throbbing headaches, persistent nausea, and multiple episodes of nonbloody emesis for several days that he attributed to his chemotherapy. He noted decreased urination without discomfort or changes in color or odor and no fatigue, fevers, chills, hematuria, flank, abdominal pain, thirst, or polydipsia. He reported no toxic ingestions or IV drug use. The patient had no relevant family history or additional social history. His outpatient medications included 10 mg cetirizine, 8 mg ondansetron, and 81 mg aspirin. On initial examination, his 137/66 mm Hg blood pressure was mildly elevated. The physical examination findings were notable for a 5-cm mass in the left neck that was firm and irregularly-shaped. His physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. He was admitted to the inpatient medicine service for an AKI complicated by symptomatic hyponatremia.

Investigations

We evaluated the patient’s AKI based on treatment responsiveness, imaging, and laboratory testing. Renal and bladder ultrasound showed no evidence of hydronephrosis or obstruction. He had a benign urinalysis with microscopy absent for protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and cellular casts. His urine pH was 5.5 (reference range, 5.0-9.0) and specific gravity was 1.011 (reference range, 1.005-1.030). His urine electrolytes revealed 45-mmol/L urine sodium (reference range, 40-220), 33-mmol/L urine chloride (reference range, 110-250), 10-mmol/L urine potassium (reference range, 25-120), 106.7-mg/dL urine creatinine (reference range, 10-400) and a calculated 2.7% fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) and 22.0-mEq/L elevated urine anion gap. As a fluid challenge, he was treated with IV 0.9% sodium chloride at 100-125 mL/h, receiving 3 liters over the first 48 hours of his hospitalization. His creatinine peaked at 9.2 mg/dL and stabilized before improving later in his hospitalization (Figure 1). The patient initially had oliguria (< 0.5 mL/kg/h), which slowly improved over his hospital course. Unfortunately, due to multiple system and clinical factors, accurate inputs and outputs were not adequately maintained during his hospitalization.

We evaluated hyponatremia with a combination of serum and urine laboratory tests. In addition to urine electrolytes, the initial evaluation focused on trending his clinical trajectory. We repeated a basic metabolic panel every 4 to 6 hours. He had 278-mOsm/kg serum osmolality (reference range, 285-295) with an effective 217-mOsm/kg serum tonicity. His urine osmolality was 270.5 mOsm/kg.

Despite administering 462 mEq sodium via crystalloid, his sodium worsened over the first 48 hours, reaching a nadir at 125 mmol/L on hospital day 3 (Figure 2). While he continued to appear euvolemic on physical examination, his blood pressure became difficult to control with 160- to 180-mm Hg systolic blood pressure readings. His thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) was normal and aldosterone was low (4 ng/dL). Additional urine studies, including a 24-hour urine sample, were collected for further evaluation. His urine uric acid was 140 mg/d (reference range, 120-820); his serum uric acid level was 8.2 mg/dL (reference range, 3.0-9.0). His 24-hour urine creatinine was 0.57 g/d (reference range, 0.50-2.15) and uric acid to creatinine ratio was 246 mg/g (reference range, 60-580). His serum creatinine collected from the same day as his 24-hour urine sample was 7.3 mg/dL. His fractional excretion of uric acid (FEurate) was 21.9%.

Differential Diagnosis

The patient’s recent administration of cisplatin raised clinical suspicion of cisplatin-induced AKI. To avoid premature diagnostic closure, we used a systematic approach for thinking about our patient’s AKI, considering prerenal, intrarenal, and postrenal etiologies. The unremarkable renal and bladder ultrasound made a postrenal etiology unlikely. The patient’s 2.7% FENa in the absence of a diuretic, limited responsiveness to crystalloid fluid resuscitation, 7.5 serum BUN/creatinine ratio, and 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality suggested an intrarenal etiology, which can be further divided into problems with glomeruli, tubules, small vessels, or interstitial space. The patient’s normal urinary microscopy with no evidence of protein, blood, ketones, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, or cellular casts made a glomerular etiology less likely. The acute onset and lack of additional systemic features, other than hypertension, made a vascular etiology less likely. A tubular etiology, such as acute tubular necrosis (ATN), was highest on the differential and was followed by an interstitial etiology, such as acute interstitial nephritis (AIN).

Patients with drug-induced AIN commonly present with signs and symptoms of an allergic-type reaction, including fever, rash, hematuria, pyuria, and costovertebral angle tenderness. The patient lacked these symptoms. However, cisplatin is known to cause ATN in up to 20-30% of patients.7 Therefore, despite the lack of the classic muddy-brown, granular casts on urine microscopy, cisplatin-induced ATN remained the most likely etiology of his AKI. Moreover, ATN can cause hyponatremia. ATN is characterized by 3 phases: initiation, maintenance, and recovery phases.8 Hyponatremia occurs during the recovery phase, typically starting weeks after renal insult and associated with high urine output and diuresis. This patient presented 1 week after injury and had persistent oliguria, making ATN an unlikely culprit of his hyponatremia.

Our patient presented with hypotonic hyponatremia with a 131 mmol/L initial sodium level and an < 280 mOsm/kg effective serum osmolality, or serum tonicity. The serum tonicity is equivalent to the difference between the measured serum osmolality and the BUN. In the setting of profound AKI, this adjustment is essential for correctly categorizing a patient’s hyponatremia as hyper-, iso-, or hypotonic. The differential diagnosis for this patient’s hypotonic hyponatremia included dilutional effects of hypervolemia, SIADH, hyperthyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and RSWS. The patient’s volume examination, lack of predisposing comorbidities or suggestive biomarkers, and > 20 mmol/L urinary sodium made hypervolemia unlikely. His urinary osmolality and specific gravity made primary polydipsia unlikely. We worked up his hyponatremia according to a diagnostic algorithm (eAppendix available at doi:10.12788/fp.0198).

The patient had a 217 mOsm/kg serum tonicity and a 270.5 mOsm/kg urine osmolality, consistent with impaired water excretion. His presentation, TSH, and concordant decrease in sodium and potassium made an endocrine etiology of his hyponatremia less likely. In hindsight, a serum cortisol would have been beneficial to more completely exclude adrenal insufficiency. His urine sodium was elevated at 45 mmol/L, raising concern for RSWS or SIADH. The FEurate helped to distinguish between SIADH and RSWS. While FEurate is often elevated in both SIADH and RSWS initially, the FEurate normalizes in SIADH with normalization of the serum sodium. The ideal cutoff for posthyponatremia correction FEurate is debated; however, a FEurate value after sodium correction < 11% suggests SIADH while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.9 Our patient’s FEurate following the sodium correction (serum sodium 134 mmol/L) was 21.9%, most suggestive of RSWS.

Treatment

Upon admission, initial treatment focused on resolving the patient’s AKI. The oncology team discontinued the cisplatin-based chemotherapy. His medication dosages were adjusted for his renal function and additional nephrotoxins avoided. In consultation, the nephrology service recommended 100 mL/h fluid resuscitation. After the patient received 3 L of 0.9% sodium chloride, his creatinine showed limited improvement and his sodium worsened, trending from 131 mmol/L to a nadir of 125 mmol/L. We initiated oral free-water restriction while continuing IV infusion of 0.9% sodium chloride at 125 mL/h.

We further augmented his sodium intake with 1-g sodium chloride tablets with each meal. By hospital day 6, the patient’s serum sodium, BUN, and creatinine improved to 130 mEq/L, 50 mg/dL, and 7.7 mg/dL, respectively. We then discontinued the oral sodium chloride tablets, fluid restriction, and IV fluids in a stepwise fashion prior to discharge. At discharge, the patient’s serum sodium was 136 mEq/L and creatinine, 4.8 mg/dL. The patient’s clinical course was complicated by symptomatic hypertension with systolic blood pressures about 180 mm Hg, requiring intermittent IV hydralazine, which was transitioned to daily nifedipine. Concerned that fluid resuscitation contributed to his hypertension, the patient also received several doses of furosemide. At time of discharge, the patient remained hypertensive and was discharged with nifedipine 90 mg daily.

Outcome and Follow-up

The patient has remained stable clinically since discharge. One week after discharge, his serum sodium and creatinine were 138 mmol/L and 3.8 mg/dL, respectively. More than 1 month after discharge, his sodium remains in the reference range and his creatinine was stable at about 3.5 mg/dL. He continues to follow-up with nephrology, oncology, and radiation oncology. He has restarted chemotherapy with a carboplatin-based regimen without recurrence of hyponatremia or AKI. His blood pressure has gradually improved to the point where he no longer requires nifedipine.

Discussion

The US Food and Drug Administration first approved the use of cisplatin, an alkylating agent that inhibits DNA replication, in 1978 for the treatment of testicular cancer.10 Since its approval, cisplatin has increased in popularity and is now considered one of the most effective antineoplastic agents for the treatment of solid tumors.1 Unfortunately, cisplatin has a well-documented adverse effect profile that includes neurotoxicity, gastrointestinal toxicity, nephrotoxicity, and ototoxicity.4 Despite frequent nephrotoxicity, cisplatin only occasionally causes hyponatremia and rarely causes RSWS, a known but potentially fatal complication. Moreover, the combination of AKI and RSWS is unique. Our patient presented with the unique combination of AKI and hyponatremia, most consistent with RSWS, likely precipitated from cisplatin chemotherapy. Through this case, we review cisplatin-associated electrolyte abnormalities, highlight the challenge of differentiating SIADH and RSWS, and suggest a treatment approach for hyponatremia during the period of diagnostic uncertainty.

Blachley and colleagues first discussed renal and electrolyte disturbances, specifically magnesium wasting, secondary to cisplatin use in 1981. In 1984, Kurtzberg and colleagues noted salt wasting in 2 patients receiving cisplatin therapy. The authors suggested that cisplatin inhibits solute transport in the thick ascending limb, causing clinically significant electrolyte abnormalities, coining the term cisplatin-induced salt wasting.11

The prevalence of cisplatin-induced salt wasting is unclear and likely underreported. In 1988, Hutchinson and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study and noted 10% of patients (n = 70) developed RSWS at some point over 18 months of cisplatin therapy—a higher rate than previously estimated.12 In 1992, another prospective cohort study evaluated the adverse effects of 47 patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin and reported hyponatremia in 43% of its 93 courses of chemotherapy. The authors did not report the etiology of these hyponatremia cases.13 Given the diagnostic challenge, RSWS may be underrepresented as a confirmed etiology of hyponatremia in cisplatin treatment.

Hyponatremia from cisplatin may present as either SIADH or RSWS, complicating treatment decisions. Both conditions lead to hypotonic hyponatremia with urine osmolality > 100 mOSm/kg and urine sodium levels > 40 mmol/L. However, pathophysiology behind SIADH and RSWS is different. In RSWS, proximal tubule damage causes hyponatremia, decreasing sodium reabsorption, and leading to impaired concentration gradient in every segment of the nephron. As a result, RSWS can lead to profound hyponatremia. Treatment typically consists of increasing sodium intake to correct serum sodium with salt tablets and hypertonic sodium chloride while treating the underlying etiology, in our case removing the offending agent, and waiting for proximal tubule function to recover.6 On the other hand, in SIADH, elevated antidiuretic hormone (ADH) increases water reabsorption in the collecting duct, which has no impact on concentration gradients of the other nephron segments.14 Free-water restriction is the hallmark of SIADH treatment. Severe SIADH may require sodium repletion and/or the initiation of vaptans, ADH antagonists that competitively inhibit V2 receptors in the collecting duct to prevent water reabsorption.15

Our patient had an uncertain etiology of his hyponatremia throughout most of his treatment course, complicating our treatment decision-making. Initially, his measured serum osmolality was 278 mOsm/kg; however, his effective tonicity was lower. His AKI elevated his BUN, which in turnrequired us to calculate his serum tonicity (217 mOsm/kg) that was consistent with hypotonic hyponatremia. His elevated urine osmolality and urine sodium levels made SIADH and RSWS the most likely etiologies of his hyponatremia. To confirm the etiology, we waited for correction of his serum sodium. Therefore, we treated him with a combination of sodium repletion with 0.9% sodium chloride (154 mEq/L), hypertonic relative to his serum sodium, sodium chloride tablets, and free-water restriction. In this approach, we attempted to harmonize the treatment strategies for both SIADH and RSWS and effectively corrected his serum sodium. We evaluated his response to our treatment with a basic metabolic panel every 6 to 8 hours. Had his serum sodium decreased < 120 mmol/L, we planned to transfer the patient to the intensive care unit for 3% sodium chloride and/or intensification of his fluid restriction. A significant worsening of his hyponatremia would have strongly suggested hyponatremia secondary to SIADH since isotonic saline can worsen hyponatremia due to increased free-water reabsorption in the collecting duct.16

To differentiate between SIADH and RSWS, we relied on the FEurate after sodium correction. Multiple case reports from Japan have characterized the distinction between the processes through FEurate and serum uric acid. While the optimal cut-off values for FEurate require additional investigation, values < 11% after serum sodium correction suggests SIADH, while a value > 11% suggests RSWS.17 Prior cases have also emphasized serum hypouricemia as a distinguishing characteristic in RSWS. However, our case illustrates that serum hypouricemia is less reliable in the setting of AKI. Due to his severe AKI, our patient could not efficiently clear uric acid, likely contributing to his hyperuricemia.

Ultimately, our patient had an FEurate > 20%, which was suggestive of RSWS. Nevertheless, we recognize limitations and confounders in our diagnosis and have reflected on our diagnostic and management choices. First, the sensitivity and specificity of postsodium correction FEurate is unknown. Tracking the change in FEurate with our interventions would have increased our diagnostic utility, as suggested by Maesaka and colleagues.14 Second, our patient’s serum sodium was still at the lower end of the reference range after treatment, which may decrease the specificity of FEurate. Third, a plasma ADH collected during the initial phase of symptomatic hyponatremia would have helped differentiate between SIADH and RSWS.

Other diagnostic tests that could have excluded alternative diagnoses with even greater certainty include plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone, B-type natriuretic peptide, renin, cortisol, and thyroid function tests. From a practical standpoint, these laboratory results (excluding thyroid function test and brain natriuretic peptide) would have taken several weeks to result at our institution, limiting their clinical utility. Similarly, FEurate also has limited clinical utility, requiring effective treatment as part of the diagnostic test. Therefore, we recommend focusing on optimal treatment for hyponatremia of uncertain etiology, especially where SIADH and RSWS are the leading diagnoses.

Conclusions

We described a rare case of concomitant cisplatin-induced severe AKI and RSWS. We have emphasized the diagnostic challenge of distinguishing between SIADH and RSWS, especially with concomitant AKI, and have acknowledged that optimal treatment relies on accurate differentiation. However, differentiation may not be clinically feasible. Therefore, we suggest a treatment strategy that incorporates both free-water restriction and sodium supplementation via IV and/or oral administration.

1. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364-378. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025

2. Holditch SJ, Brown CN, Lombardi AM, Nguyen KN, Edelstein CL. Recent advances in models, mechanisms, biomarkers, and interventions in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):3011. Published 2019 Jun 20. doi:10.3390/ijms20123011

3. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The “accidental” cure—platinum-based treatment for cancer: the discovery of cisplatin. Published May 30, 2014. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/cisplatin

4. Ozkok A, Edelstein CL. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:967826. doi:10.1155/2014/967826

5. Palmer LG, Schnermann J. Integrated control of Na transport along the nephron. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(4):676-687. doi:10.2215/CJN.12391213

6. Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315. doi:10.2215/CJN.02740608

7. Shirali AC, Perazella MA. Tubulointerstitial injury associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):56-63. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2013.06.010

8. Agrawal M, Swartz R. Acute renal failure [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician 2001 Feb 1;63(3):445]. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2077-2088.

9. Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

10. Monneret C. Platinum anticancer drugs. From serendipity to rational design. Ann Pharm Fr. 2011;69(6):286-295. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2011.10.001

11. Kurtzberg J, Dennis VW, Kinney TR. Cisplatinum-induced renal salt wasting. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1984;12(2):150-154. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950120219

12. Hutchison FN, Perez EA, Gandara DR, Lawrence HJ, Kaysen GA. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with cisplatin. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(1):21-25. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-21

13. Lee YK, Shin DM. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with high-dose cisplatin, etoposide, and mitomycin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 1992;7(2):118-121. doi:10.3904/kjim.1992.7.2.118

14. Maesaka JK, Imbriano L, Mattana J, Gallagher D, Bade N, Sharif S. Differentiating SIADH from cerebral/renal salt wasting: failure of the volume approach and need for a new approach to hyponatremia. J Clin Med. 2014;3(4):1373-1385. Published 2014 Dec 8. doi:10.3390/jcm3041373

15. Palmer BF. The role of v2 receptor antagonists in the treatment of hyponatremia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2013;11(1):1-8. doi:10.5049/EBP.2013.11.1.1

16. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-S21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001

17. Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Miyawaki N. High prevalence of renal salt wasting without cerebral disease as cause of hyponatremia in general medical wards. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(1):15-22. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.03.02

1. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:364-378. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025

2. Holditch SJ, Brown CN, Lombardi AM, Nguyen KN, Edelstein CL. Recent advances in models, mechanisms, biomarkers, and interventions in cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(12):3011. Published 2019 Jun 20. doi:10.3390/ijms20123011

3. National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The “accidental” cure—platinum-based treatment for cancer: the discovery of cisplatin. Published May 30, 2014. Accessed November 10, 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/cisplatin

4. Ozkok A, Edelstein CL. Pathophysiology of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:967826. doi:10.1155/2014/967826

5. Palmer LG, Schnermann J. Integrated control of Na transport along the nephron. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(4):676-687. doi:10.2215/CJN.12391213

6. Bitew S, Imbriano L, Miyawaki N, Fishbane S, Maesaka JK. More on renal salt wasting without cerebral disease: response to saline infusion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):309-315. doi:10.2215/CJN.02740608

7. Shirali AC, Perazella MA. Tubulointerstitial injury associated with chemotherapeutic agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21(1):56-63. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2013.06.010

8. Agrawal M, Swartz R. Acute renal failure [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician 2001 Feb 1;63(3):445]. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2077-2088.

9. Milionis HJ, Liamis GL, Elisaf MS. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. CMAJ. 2002;166(8):1056-1062.

10. Monneret C. Platinum anticancer drugs. From serendipity to rational design. Ann Pharm Fr. 2011;69(6):286-295. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2011.10.001

11. Kurtzberg J, Dennis VW, Kinney TR. Cisplatinum-induced renal salt wasting. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1984;12(2):150-154. doi:10.1002/mpo.2950120219

12. Hutchison FN, Perez EA, Gandara DR, Lawrence HJ, Kaysen GA. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with cisplatin. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(1):21-25. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-1-21

13. Lee YK, Shin DM. Renal salt wasting in patients treated with high-dose cisplatin, etoposide, and mitomycin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 1992;7(2):118-121. doi:10.3904/kjim.1992.7.2.118

14. Maesaka JK, Imbriano L, Mattana J, Gallagher D, Bade N, Sharif S. Differentiating SIADH from cerebral/renal salt wasting: failure of the volume approach and need for a new approach to hyponatremia. J Clin Med. 2014;3(4):1373-1385. Published 2014 Dec 8. doi:10.3390/jcm3041373

15. Palmer BF. The role of v2 receptor antagonists in the treatment of hyponatremia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2013;11(1):1-8. doi:10.5049/EBP.2013.11.1.1

16. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Schrier RW, Sterns RH. Hyponatremia treatment guidelines 2007: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2007;120(11 Suppl 1):S1-S21. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.001

17. Maesaka JK, Imbriano LJ, Miyawaki N. High prevalence of renal salt wasting without cerebral disease as cause of hyponatremia in general medical wards. Am J Med Sci. 2018;356(1):15-22. doi:10.1016/j.amjms.2018.03.02