User login

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

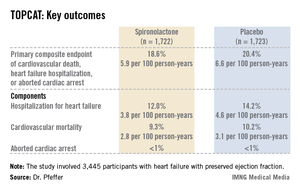

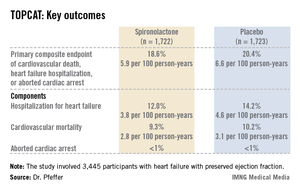

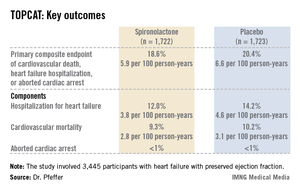

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

DALLAS – Spironolactone did not hit a home run in the large international "treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist" (TOPCAT) trial, but it did knock out a solid single in the form of significantly reduced hospitalizations for this extremely common, chronic, high morbidity/mortality condition.

It was this positive result for an important prespecified secondary outcome that enabled TOPCAT to avoid becoming roadkill. Technically, TOPCAT was a negative clinical trial in that spironolactone did not significantly outperform placebo on the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular mortality, heart failure hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest.

Yet that negative primary outcome was controversial: The aldosterone antagonist actually showed a significant positive result for the composite endpoint in North and South American participants, yet the results were resoundingly negative – and also considerably out of whack with the characteristic arc of progressive heart failure – among the nearly one-half of TOPCAT participants in Russia and the Republic of Georgia.

"What happened in Russia and Georgia we just don’t understand," Dr. Bertram Pitt, TOPCAT steering committee chair, said in an interview, shaking his head. "The event rate with placebo in Eastern Europe was so low it’s not compatible with anything we know about heart failure. The signs and symptoms of HFpEF [heart failure with preserved ejection fraction] are nonspecific; they can be due to obesity, lung disease, and other things. Clearly there are some people getting into the major trials of HFpEF that probably don’t have it."

TOPCAT was a randomized, double-blind clinical trial comprising 3,445 participants with symptomatic HFpEF at 250 sites in the United States and five other countries. They were randomized to spironolactone or placebo and followed prospectively for a mean of 3.3 years. The starting dose of the aldosterone antagonist was 15 mg/day, with a target of 30 mg/day. The drug could be titrated within the range of 15-45 mg/day. Eight months into the trial, the mean daily dose was 25 mg.

Presenting the TOPCAT results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions, Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer noted that the primary composite endpoint occurred in 20.4% of placebo-treated controls and 18.6% on spironolactone, a statistically nonsignificant difference. In contrast, the 17% reduction in the rate of hospitalization for HFpEF in the spironolactone group relative to controls was significant (P = .04). Moreover, the spironolactone-treated patients had a collective 394 HFpEF hospitalizations, markedly fewer than the 475 in controls. This translated to a hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurring at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Hyperkalemia in excess of 5.5 mmol/L occurred in 18.7% of the spironolactone group, twice the rate of controls (9.1%). And the incidence of a creatinine level more than double the upper limit of normal was 49% greater in the spironolactone group. That said, neither of these laboratory abnormalities resulted in any serious adverse consequences because investigators adjusted the dose in response, explained Dr. Pfeffer, professor of medicine at Harvard University, Boston.

He drew special attention to two points: The primary composite event rate in placebo-treated patients in the Americas was 31.8% consistent with what has been seen in other studies of HFpEF – compared to a mere 8.4% in Eastern Europe. And patients who qualified for TOPCAT on the basis of an elevated natriuretic peptide level had a primary endpoint rate of 15.9% with spironolactone, a highly significant 35% reduction compared with the 23.6% in controls, suggesting that an elevated baseline natriuretic peptide level may be a biomarker useful in identifying those HFpEF patients most likely to respond to an aldosterone antagonist.

Dr. Pfeffer said that because the pharmaceutical industry has zero interest in spironolactone and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), which sponsored TOPCAT, has finite resources, he doubts there will be any further large studies of the drug in HFpEF.

"One is going to have to make decisions based on this trial. I don’t see another trial behind us," the cardiologist said.

And while TOPCAT was flawed, he said it contains a compelling message for clinicians: "I think we have an important finding here. We’re very confident that with this generic medication, which costs pennies per day, we can reduce hospitalizations for heart failure, which are the major burden in patients with HFpEF."

Discussant Dr. Margaret M. Redfield was more cautious. While there was a sound rationale for studying spironolactone in HFpEF based upon its impressive benefits in systolic heart failure as shown in earlier landmark clinical trials, given that the drug didn’t result in a significant reduction in all-cause hospitalizations, she said she wants to see evidence of improved patient-centered outcomes, such as quality of life, before prescribing spironolactone for HFpEF.

"One has to worry that the problems with worsening renal function and hyperkalemia may be much more common in clinical practice than in the highly monitored environment of a clinical trial," added Dr. Redfield, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Other heart failure experts not involved in TOPCAT took a more positive view of the study.

Dr. Clyde W. Yancy, AHA spokesperson, said in an interview that HFpEF is probably even more common than systolic heart failure, and it is a disease for which physicians have had no proven-effective treatments.

"You can almost justifiably say, ‘Let’s just look at the Americas, where patients had event rates that are consistent with the disease we think we understand.’ And it looks like there’s a signal there. I think that there’s enough evidence in TOPCAT for the clinical pragmatist to be able to be comfortable that spironolactone is probably beneficial and can be given safely. If you are convinced you can give it safely in your own clinical scenario, I think you should use it," said Dr. Yancy, professor of medicine and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr. Marco Metra, a cardiologist at the University of Brescia (Italy), said he interprets the TOPCAT results as an indication for prescribing spironolactone, at least in HFpEF patients with high natriuretic peptide levels or multiple heart failure hospitalizations.

Dr. Pitt, emeritus professor of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, emphasized that in prescribing spironolactone, whether for HFpEF or systolic heart failure, it’s obligatory to measure potassium and creatinine levels at baseline, when changing the dose, and at each routine follow-up visit, titrating in response to the results. Failure to do so is akin to prescribing warfarin for a patient with atrial fibrillation and then never measuring the INR (international normalized ratio) he said.

TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to numerous pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Major finding: Hospitalization for heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction occurred at a rate of 3.8 per 100 person-years in patients randomized to spironolactone, a significant 17% risk reduction compared with the 4.6 per 100 person-years in placebo-treated controls.

Data source: TOPCAT, a randomized, double-blind, six-country clinical trial involving 3,445 patients with symptomatic heart failure and an ejection fraction of 45% or more.

Disclosures:. TOPCAT was sponsored by the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Pfeffer and Dr. Pitt serve as consultants to pharmaceutical companies that had no involvement in the trial.