User login

Child of The New Gastroenterologist

Lessons learned as a gastroenterologist on social media

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

I have always been a strong believer in meeting patients where they obtain their health information. Early in my clinical training, I realized that patients are exposed to health information through traditional media formats and, increasingly, social media, rather than brief clinical encounters. Unlike traditional media, social media allows individuals the opportunity to post information without a third-party filter. However, this opens the door for untrained individuals to spread misinformation and disinformation. In health care, this could potentially disrupt public health efforts. Even innocent mistakes like overlooking the appropriate clinical context can cause issues. Traditional media outlets also have agendas that may leave certain conditions, therapies, and other facets of health care underrepresented. My belief is that experts should therefore be trained and incentivized to be spokespeople for their own areas of expertise. Furthermore, social media provides a novel opportunity to improve health literacy while humanizing and restoring fading trust in health care.

There are several items to consider before initiating on one’s social media journey: whether you are committed to exploring the space, what one’s purpose is on social media, who the intended target audience is, which platform is most appropriate to serve that purpose and audience, and what potential pitfalls there may be.

The first question to ask oneself is whether you are prepared to devote time to cultivating a social media presence and speak or be heard publicly. Regardless of the platform, a social media presence requires consistency and audience interaction. The decision to partake can be personal; I view social media as an extension of in-person interaction, but not everyone is willing to commit to increased accessibility and visibility. Social media can still be valuable to those who choose to observe and learn rather than post.

Next is what one’s purpose is with being on social media. This can vary from peer education, boosting health literacy for patients, or using social media as a news source, networking tool, or a creative outlet. While my social media activity supports all these, my primary purpose is the distribution of accurate health information as a trained expert. When I started, I was one of few academic gastroenterologists uniquely positioned to bridge the elusive gap between the young, Gen Z crowd and academic medicine. Of similar importance is defining one’s target audience: patients, trainees, colleagues, or the general public.

Because there are numerous social media platforms, and only more to come in the future, it is critical to focus only on platforms that will serve one’s purpose and audience. Additionally, some may find more joy or agility in using one platform over the other. While I am one of the few clinicians who are adept at building communities across multiple rapidly evolving social media platforms, I will be the first to admit that it takes time to fully understand each platform with its ever-growing array of features. I find myself better at some platforms over others and, depending on my goals, I often will shift my focus from one to another.

Each platform has its pros and cons. Twitter is perhaps the most appropriate platform for starters. Easy to use with the least preparation necessary for every post, it also serves as the primary platform for academic discussion among all the popular social media platforms. Over the past few years, hundreds of gastroenterologists have become active on Twitter, which allows for ample networking opportunities and potential collaborations. The space has evolved to house various structured chats and learning opportunities as described by accounts like @MondayNightIBD, @ScopingSundays, #TracingTuesday, and @GIJournal. All major GI journals and societies are also present on Twitter and disseminating the latest information. Now a vestige of the past when text within tweets was not searchable, hashtags were used to curate discussion because searching by hashtag could reveal the latest discussion surrounding a topic and help identify others with a similar interest. Hashtags now remain relevant when crafting tweets, as the strategic inclusion of hashtags can help your content reach those who share an interest. A hashtag ontology was previously published to standardize academic conversation online in gastroenterology. Twitter also boasts features like polls that also help audiences engage.

Twitter has its disadvantages, however. Conversation is often siloed and difficult to reach audiences who don’t already follow you or others associated with you. Tweets disappear quickly in one’s feed and are often not seen by your followers. It lacks the visual appeal of other image- and video-based platforms that tend to attract more members of the general public. (Twitter lags behind these other platforms in monthly users) Other platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok have other benefits. Facebook may help foster community discussions in groups and business pages are also helpful for practice promotion. Instagram has gained popularity for educational purposes over the past 2 years, given its pairing with imagery and room for a lengthier caption. It has a variety of additional features like the temporary Instagram Stories that last 24 hours (which also allows for polling), question and answer, and livestream options. Other platforms like YouTube and TikTok have greater potential to reach audiences who otherwise would not see your content, with the former having the benefit of being highly searchable and the latter being the social media app with fastest growing popularity.

Having grown up with the Internet-based instant messaging and social media platforms, I have always enjoyed the medium as a way to connect with others. However, productive engagement on these platforms came much later. During a brief stint as part of the ABC News medical unit, I learned how Twitter was used to facilitate weekly chats around a specific topic online. I began exploring my own social media voice, which quickly gave way to live-tweeting medical conferences, hosting and participating Twitter chats myself, and guiding colleagues and professional societies to greater adoption of social media. In an attempt to introduce a divisional social media account during my fellowship, I learned of institutional barriers including antiquated policies that actively dissuaded social media use. I became increasingly involved on committees in our main GI societies after engaging in multiple research projects using social media data looking at how GI journals promote their content online, the associations between social media presence and institutional ranking, social media behavior at medical conferences, and the evolving perspectives of training program leadership regarding social media.

The pitfalls of social media remain a major concern for physicians and employers alike. First and foremost, it is important to review one’s institutional social media policy prior to starting, as individuals are ultimately held to their local policies. Not only can social media activity be a major liability for a health care employer, but also in the general public’s trust in health professionals. Protecting patient privacy and safety are of utmost concern, and physicians must be mindful not to inadvertently reveal patient identity. HIPAA violations are not limited to only naming patients by name or photo; descriptions of procedural cases and posting patient-related images such as radiographs or endoscopic images may reveal patient identity if there are unique details on these images (e.g., a radio-opaque necklace on x-ray or a particular swallowed foreign body).

Another disadvantage of social media is being approached with personal medical questions. I universally decline to answer these inquiries, citing the need to perform a comprehensive review of one’s medical chart and perform an in-person physical exam to fully assess a patient. The distinction between education and advice is subtle, yet important to recognize. Similarly, the need to uphold professionalism online is important. Short messages on social media can be misinterpreted by colleagues and the public. Not only can these interactions be potentially detrimental to one’s career, but it can further erode trust in health care if patients perceive this as fragmentation of the health care system. On platforms that encourage humor and creativity like TikTok, there have also been medical professionals and students publicly criticized and penalized for posting unprofessional content mocking patients.

With the introduction of social media influencers in recent years, some professionals have amassed followings, introducing yet another set of concerns. One is being approached with sponsorship and endorsement offers, as any agreements must be in accordance with institutional policy. As one’s following grows, there may be other concerns of safety both online and in real life. Online concerns include issues with impersonation and use of photos or written content without permission. On the surface this may not seem like a significant concern, but there have been situations where family photos are distributed to intended audiences or one’s likeness is used to endorse a product.

In addition to physical safety, another unintended consequence of social media use is its impact on one’s mental health. As social media tends to be a highlight reel, it is easy to be consumed by comparison with colleagues and their lives on social media, whether it truly reflects one’s actual life or not.

My ability to understand multiple social media platforms and anticipate a growing set of risks and concerns with using social media is what led to my involvement with multiple GI societies and appointment by my institution’s CEO to serve as the first chief medical social media officer. My desire to help other professionals with the journey also led to the formation of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, the first 501(c)(3) nonprofit professional organization devoted to health professionals on social media. There is tremendous opportunity to impact public health through social media, especially with regards to raising awareness about underrepresented conditions and presenting information that is accurate. Many barriers remain to the widespread adoption of social media by health professionals, such as the lack of financial or academic incentives. For now, there is every indication that social media is here to stay, and it will likely continue to play an important role in how we communicate with our patients.

AGA can be found online at @AmerGastroAssn (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) and @AGA_Gastro, @AGA_CGH, and @AGA_CMGH (Facebook and Twitter).

Dr. Chiang is assistant professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology & hepatology, director, endoscopic bariatric program, chief medical social media officer, Jefferson Health, Philadelphia, and president, Association for Healthcare Social Media, @austinchiangmd

Gastroenterology practice evaluations: Can patients get satisfaction?

Although largely untouched by the first and second industrial revolutions in the 18th and 20th centuries, the practice of medicine in the 21st century is increasingly susceptible to the vast transformative power of the third – and rapidly approaching fourth – industrial revolutions. New technological advances and their associated distribution of knowledge and connectedness have allowed patients unprecedented access to health care information. The salutary effects of this change is manifest in a diversity of areas, including registries that facilitate participation in state of the art research such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the ability to track nascent trends in infectious diseases with Google searches.1

Although the stakes may seem lower when patients go online to choose a practitioner, the reality demonstrates just how important those search results can be. With parallels of similar trends in other sectors, there is an increasing emphasis on ranking health care facilities, practitioners, and medical experiences. This phenomenon extends beyond private Internet sites into government scorecards, which has significant implications. But even with widespread access to information, there is frequently a lack of context for interpreting these data. Consequently, it is worth exploring why measuring satisfaction can be important, how patients can rate practitioners, and what to do with the available information to improve care delivery.

The idea to measure patient satisfaction of delivered health care began in earnest during the 1980s with Irwin Press and Rodney Ganey collaborating to create formal processes for collecting data on the “salient aspects of ... health care experience, [involving] the interaction of expectations, preferences, and satisfaction with medical care.”2,3 The enthusiasm for collecting these data has grown greatly since that time. More recently, the federal government began obtaining data in 2002 when the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) collaborated to develop a standardized questionnaire for hospitalized patients known as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, or HCAHPS.4 Subsequently, standardized survey instruments have been developed for nearly every phase of care, including outpatient care (CG-CAHPS), emergency care (ED-CAHPS), and ambulatory surgery care (OAS-CAHPS). These instruments are particularly relevant to gastroenterologists, with questions querying patients about preprocedure instructions, surgery center check-in processes, comfort of procedure and waiting rooms, friendliness of providers, and quality of postprocedure information.

The focus on rating satisfaction intensified in 2010 after the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Around this time, patient satisfaction and health outcomes became more deeply integrated concepts in health care quality. As part of a broader emphasis in this area, CMS initiated the hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program, which tied incentive payments for Medicare beneficiaries to hospital-based health care quality and patient satisfaction. Within this schema, 25% of performance, and its associated economic stakes, is measured by HCAHPS scores.5 Other value programs such as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment Program (MIPS) include CAHPS instruments as optional assessments of quality.

Given the financial risks linked to satisfaction rankings and their online visibility, many argue that patient satisfaction is prioritized in organizations above more clinically meaningful metrics. Studies have shown, however, that high levels of patient satisfaction can lead to increased patient loyalty, treatment adherence, patient retention, staff morale, and personal and professional satisfaction.6,7 In fact, not surprisingly, there is an inverse correlation between patient satisfaction and the rates of malpractice lawsuits.7-10

Despite the growing relevance of patient perceptions to clinical practice, measuring satisfaction remains a challenge. While current metrics are particular to an individual patient’s experiences, underlying health conditions influence opinions of these episodes of care. Specifically, patients with depression and anxiety are, in general, less satisfied with the care they receive.11,12 Similarly, patients with chronic diseases on multiple medications and those with more severe symptoms are commonly less satisfied with their care than are patients with acute issues2 and with milder symptoms.3 As gastroenterologists, seeing sicker patients with chronic conditions is not uncommon, and this could serve as a disadvantage when compared with peers in other specialties because scores are not typically adjusted.

Since patient-centered metrics are likely to remain relevant in the future, and with the unique challenges this can present to practicing gastroenterologists, achieving higher degrees of patient satisfaction remains both aspirational and difficult. We will be asked to reconcile and manage not only clinical conundrums but also seemingly conflicting realities of patient preferences. For example, it has been shown that, among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), more testing led to higher satisfaction only until that testing was performed within the context of a gastroenterologist’s care.13 In contrast, within the endoscopy setting, a preprocedure diagnosis of IBS did not increase the risk for procedure-related dissatisfaction, provided patients were not prescribed chronic psychotropic medication, nervous prior to the procedure, distressed or in pain during the procedure, or had unmet physical or emotional needs during the procedure.14 Furthermore, there is poor correlation between endoscopic quality measures with strong evidence – such as adenoma detection rate, withdrawal time, and cecal intubation rate – and patient satisfaction.15

So, when considering these conflicting findings and evidence that patients’ global rating of their health care is not reliably associated with the quality of the care they receive,16 should we emphasize experience over outcome? As clinicians practicing in an increasingly transparent and value-based health care environment, we are subject to many priorities contending for our attention. We strive to provide care that is at once patient centric, evidence based, and low cost; however, achieving these goals often requires different strategies. At the end of the day, our primary aim is to provide consistently excellent patient care. We believe that quality and experience are not competing principles. Patient satisfaction is relevant and important, but it should not preclude adherence to our primary responsibility of providing high-quality care.

When trying to make clinical decisions that may compromise one of these goals for another, it can be helpful to recall the “me and my family” rule: What kind of care would I want for myself or my loved ones in this situation?

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Ziad Gellad (Duke University, Durham, N.C.) for his assistance in reviewing and providing feedback on this manuscript.

1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(47):14473-8. 2. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3(4):579-94.

3. Gut. 2004;53(SUPPL. 4):40-4.

4. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(11):982-7.

5. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271-7.

6. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(4):266-73.

7. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(3):151-5.

8. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-33.

9. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-7. 10. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1583-7.

11. J Diabetes Metab. 2012;3(7):1000210.

12. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):105-10.

13. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(7):614-21.

14. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(10):1860-71.15. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(7):1089-91.

16. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665-72.

Dr. Finn is a gastroenterologist with the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Mountain View, Calif.; Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine, director of esophageal research and quality in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chair-elect of the AGA Quality Committee.

Although largely untouched by the first and second industrial revolutions in the 18th and 20th centuries, the practice of medicine in the 21st century is increasingly susceptible to the vast transformative power of the third – and rapidly approaching fourth – industrial revolutions. New technological advances and their associated distribution of knowledge and connectedness have allowed patients unprecedented access to health care information. The salutary effects of this change is manifest in a diversity of areas, including registries that facilitate participation in state of the art research such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the ability to track nascent trends in infectious diseases with Google searches.1

Although the stakes may seem lower when patients go online to choose a practitioner, the reality demonstrates just how important those search results can be. With parallels of similar trends in other sectors, there is an increasing emphasis on ranking health care facilities, practitioners, and medical experiences. This phenomenon extends beyond private Internet sites into government scorecards, which has significant implications. But even with widespread access to information, there is frequently a lack of context for interpreting these data. Consequently, it is worth exploring why measuring satisfaction can be important, how patients can rate practitioners, and what to do with the available information to improve care delivery.

The idea to measure patient satisfaction of delivered health care began in earnest during the 1980s with Irwin Press and Rodney Ganey collaborating to create formal processes for collecting data on the “salient aspects of ... health care experience, [involving] the interaction of expectations, preferences, and satisfaction with medical care.”2,3 The enthusiasm for collecting these data has grown greatly since that time. More recently, the federal government began obtaining data in 2002 when the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) collaborated to develop a standardized questionnaire for hospitalized patients known as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, or HCAHPS.4 Subsequently, standardized survey instruments have been developed for nearly every phase of care, including outpatient care (CG-CAHPS), emergency care (ED-CAHPS), and ambulatory surgery care (OAS-CAHPS). These instruments are particularly relevant to gastroenterologists, with questions querying patients about preprocedure instructions, surgery center check-in processes, comfort of procedure and waiting rooms, friendliness of providers, and quality of postprocedure information.

The focus on rating satisfaction intensified in 2010 after the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Around this time, patient satisfaction and health outcomes became more deeply integrated concepts in health care quality. As part of a broader emphasis in this area, CMS initiated the hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program, which tied incentive payments for Medicare beneficiaries to hospital-based health care quality and patient satisfaction. Within this schema, 25% of performance, and its associated economic stakes, is measured by HCAHPS scores.5 Other value programs such as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment Program (MIPS) include CAHPS instruments as optional assessments of quality.

Given the financial risks linked to satisfaction rankings and their online visibility, many argue that patient satisfaction is prioritized in organizations above more clinically meaningful metrics. Studies have shown, however, that high levels of patient satisfaction can lead to increased patient loyalty, treatment adherence, patient retention, staff morale, and personal and professional satisfaction.6,7 In fact, not surprisingly, there is an inverse correlation between patient satisfaction and the rates of malpractice lawsuits.7-10

Despite the growing relevance of patient perceptions to clinical practice, measuring satisfaction remains a challenge. While current metrics are particular to an individual patient’s experiences, underlying health conditions influence opinions of these episodes of care. Specifically, patients with depression and anxiety are, in general, less satisfied with the care they receive.11,12 Similarly, patients with chronic diseases on multiple medications and those with more severe symptoms are commonly less satisfied with their care than are patients with acute issues2 and with milder symptoms.3 As gastroenterologists, seeing sicker patients with chronic conditions is not uncommon, and this could serve as a disadvantage when compared with peers in other specialties because scores are not typically adjusted.

Since patient-centered metrics are likely to remain relevant in the future, and with the unique challenges this can present to practicing gastroenterologists, achieving higher degrees of patient satisfaction remains both aspirational and difficult. We will be asked to reconcile and manage not only clinical conundrums but also seemingly conflicting realities of patient preferences. For example, it has been shown that, among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), more testing led to higher satisfaction only until that testing was performed within the context of a gastroenterologist’s care.13 In contrast, within the endoscopy setting, a preprocedure diagnosis of IBS did not increase the risk for procedure-related dissatisfaction, provided patients were not prescribed chronic psychotropic medication, nervous prior to the procedure, distressed or in pain during the procedure, or had unmet physical or emotional needs during the procedure.14 Furthermore, there is poor correlation between endoscopic quality measures with strong evidence – such as adenoma detection rate, withdrawal time, and cecal intubation rate – and patient satisfaction.15

So, when considering these conflicting findings and evidence that patients’ global rating of their health care is not reliably associated with the quality of the care they receive,16 should we emphasize experience over outcome? As clinicians practicing in an increasingly transparent and value-based health care environment, we are subject to many priorities contending for our attention. We strive to provide care that is at once patient centric, evidence based, and low cost; however, achieving these goals often requires different strategies. At the end of the day, our primary aim is to provide consistently excellent patient care. We believe that quality and experience are not competing principles. Patient satisfaction is relevant and important, but it should not preclude adherence to our primary responsibility of providing high-quality care.

When trying to make clinical decisions that may compromise one of these goals for another, it can be helpful to recall the “me and my family” rule: What kind of care would I want for myself or my loved ones in this situation?

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Ziad Gellad (Duke University, Durham, N.C.) for his assistance in reviewing and providing feedback on this manuscript.

1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(47):14473-8. 2. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3(4):579-94.

3. Gut. 2004;53(SUPPL. 4):40-4.

4. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(11):982-7.

5. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271-7.

6. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(4):266-73.

7. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(3):151-5.

8. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-33.

9. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-7. 10. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1583-7.

11. J Diabetes Metab. 2012;3(7):1000210.

12. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):105-10.

13. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(7):614-21.

14. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(10):1860-71.15. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(7):1089-91.

16. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665-72.

Dr. Finn is a gastroenterologist with the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Mountain View, Calif.; Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine, director of esophageal research and quality in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chair-elect of the AGA Quality Committee.

Although largely untouched by the first and second industrial revolutions in the 18th and 20th centuries, the practice of medicine in the 21st century is increasingly susceptible to the vast transformative power of the third – and rapidly approaching fourth – industrial revolutions. New technological advances and their associated distribution of knowledge and connectedness have allowed patients unprecedented access to health care information. The salutary effects of this change is manifest in a diversity of areas, including registries that facilitate participation in state of the art research such as ClinicalTrials.gov and the ability to track nascent trends in infectious diseases with Google searches.1

Although the stakes may seem lower when patients go online to choose a practitioner, the reality demonstrates just how important those search results can be. With parallels of similar trends in other sectors, there is an increasing emphasis on ranking health care facilities, practitioners, and medical experiences. This phenomenon extends beyond private Internet sites into government scorecards, which has significant implications. But even with widespread access to information, there is frequently a lack of context for interpreting these data. Consequently, it is worth exploring why measuring satisfaction can be important, how patients can rate practitioners, and what to do with the available information to improve care delivery.

The idea to measure patient satisfaction of delivered health care began in earnest during the 1980s with Irwin Press and Rodney Ganey collaborating to create formal processes for collecting data on the “salient aspects of ... health care experience, [involving] the interaction of expectations, preferences, and satisfaction with medical care.”2,3 The enthusiasm for collecting these data has grown greatly since that time. More recently, the federal government began obtaining data in 2002 when the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) collaborated to develop a standardized questionnaire for hospitalized patients known as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, or HCAHPS.4 Subsequently, standardized survey instruments have been developed for nearly every phase of care, including outpatient care (CG-CAHPS), emergency care (ED-CAHPS), and ambulatory surgery care (OAS-CAHPS). These instruments are particularly relevant to gastroenterologists, with questions querying patients about preprocedure instructions, surgery center check-in processes, comfort of procedure and waiting rooms, friendliness of providers, and quality of postprocedure information.

The focus on rating satisfaction intensified in 2010 after the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Around this time, patient satisfaction and health outcomes became more deeply integrated concepts in health care quality. As part of a broader emphasis in this area, CMS initiated the hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program, which tied incentive payments for Medicare beneficiaries to hospital-based health care quality and patient satisfaction. Within this schema, 25% of performance, and its associated economic stakes, is measured by HCAHPS scores.5 Other value programs such as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment Program (MIPS) include CAHPS instruments as optional assessments of quality.

Given the financial risks linked to satisfaction rankings and their online visibility, many argue that patient satisfaction is prioritized in organizations above more clinically meaningful metrics. Studies have shown, however, that high levels of patient satisfaction can lead to increased patient loyalty, treatment adherence, patient retention, staff morale, and personal and professional satisfaction.6,7 In fact, not surprisingly, there is an inverse correlation between patient satisfaction and the rates of malpractice lawsuits.7-10

Despite the growing relevance of patient perceptions to clinical practice, measuring satisfaction remains a challenge. While current metrics are particular to an individual patient’s experiences, underlying health conditions influence opinions of these episodes of care. Specifically, patients with depression and anxiety are, in general, less satisfied with the care they receive.11,12 Similarly, patients with chronic diseases on multiple medications and those with more severe symptoms are commonly less satisfied with their care than are patients with acute issues2 and with milder symptoms.3 As gastroenterologists, seeing sicker patients with chronic conditions is not uncommon, and this could serve as a disadvantage when compared with peers in other specialties because scores are not typically adjusted.

Since patient-centered metrics are likely to remain relevant in the future, and with the unique challenges this can present to practicing gastroenterologists, achieving higher degrees of patient satisfaction remains both aspirational and difficult. We will be asked to reconcile and manage not only clinical conundrums but also seemingly conflicting realities of patient preferences. For example, it has been shown that, among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), more testing led to higher satisfaction only until that testing was performed within the context of a gastroenterologist’s care.13 In contrast, within the endoscopy setting, a preprocedure diagnosis of IBS did not increase the risk for procedure-related dissatisfaction, provided patients were not prescribed chronic psychotropic medication, nervous prior to the procedure, distressed or in pain during the procedure, or had unmet physical or emotional needs during the procedure.14 Furthermore, there is poor correlation between endoscopic quality measures with strong evidence – such as adenoma detection rate, withdrawal time, and cecal intubation rate – and patient satisfaction.15

So, when considering these conflicting findings and evidence that patients’ global rating of their health care is not reliably associated with the quality of the care they receive,16 should we emphasize experience over outcome? As clinicians practicing in an increasingly transparent and value-based health care environment, we are subject to many priorities contending for our attention. We strive to provide care that is at once patient centric, evidence based, and low cost; however, achieving these goals often requires different strategies. At the end of the day, our primary aim is to provide consistently excellent patient care. We believe that quality and experience are not competing principles. Patient satisfaction is relevant and important, but it should not preclude adherence to our primary responsibility of providing high-quality care.

When trying to make clinical decisions that may compromise one of these goals for another, it can be helpful to recall the “me and my family” rule: What kind of care would I want for myself or my loved ones in this situation?

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Ziad Gellad (Duke University, Durham, N.C.) for his assistance in reviewing and providing feedback on this manuscript.

1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(47):14473-8. 2. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3(4):579-94.

3. Gut. 2004;53(SUPPL. 4):40-4.

4. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(11):982-7.

5. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):271-7.

6. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(4):266-73.

7. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(3):151-5.

8. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-33.

9. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-7. 10. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1583-7.

11. J Diabetes Metab. 2012;3(7):1000210.

12. Am Heart J. 2000;140(1):105-10.

13. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(7):614-21.

14. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50(10):1860-71.15. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(7):1089-91.

16. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665-72.

Dr. Finn is a gastroenterologist with the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Mountain View, Calif.; Dr. Leiman is assistant professor of medicine, director of esophageal research and quality in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University, Duke Clinical Research Institute, and chair-elect of the AGA Quality Committee.

Mentoring during fellowship to improve career fit, decrease burnout, and optimize career satisfaction among young gastroenterologists

Introduction

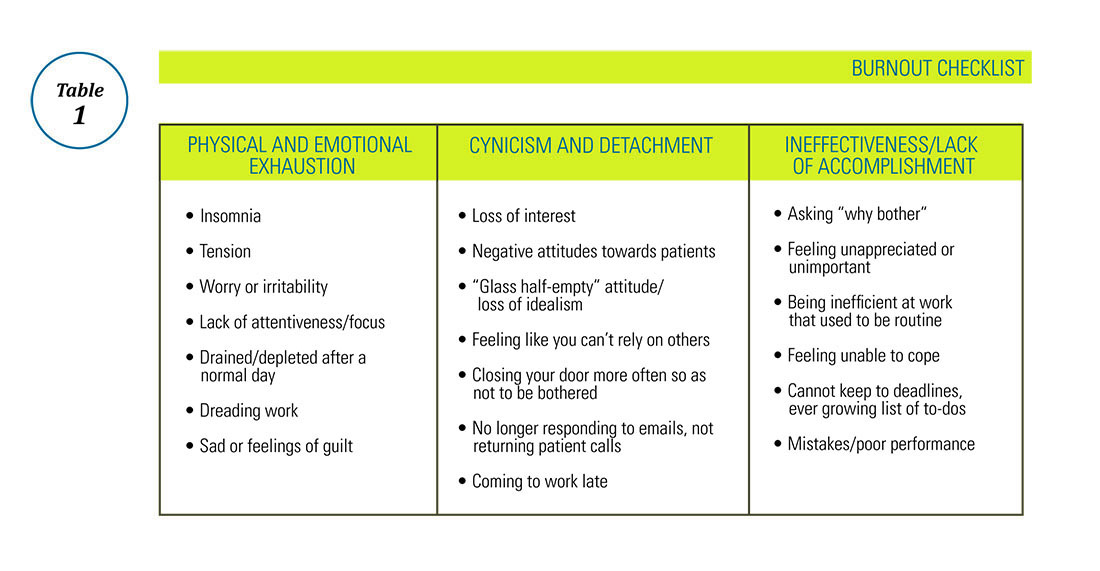

Burnout in physicians has received significant attention within the past several years, particularly among trainees and early-career physicians. The subspecialties of gastroenterology and hepatology are not immune to burnout, with multiple studies indicating that early career gastroenterologists may be disproportionately affected, compared with their more-established counterparts.1-4 Although the drivers of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment among trainees and early-career gastroenterologists are not fully understood, maximizing career fit during the transition from fellowship into the first posttraining position has been promoted as a potential method to decrease burnout in this population.4,5

While most trainees enter gastroenterology fellowships with a set of predefined career goals, mentorship during fellowship can provide critical guidance along with exposure to new areas and career tracks that were not previously considered. In a survey of gastroenterology and transplant hepatology fellows, 94% of participants with a mentor reported that the mentor significantly influenced their career decision.6 Effective mentoring also has been identified as one possible method to decrease burnout among trainees.7,8

Formal mentoring in gastroenterology fellowship programs might decrease burnout through effectively identifying risk factors such as work hour violations or a lack of social support. Additionally, when fellows are being prepared for transition to their first positions as attending gastroenterologists, there is a critical opportunity to improve career fit and decrease burnout rates among early-career gastroenterologists. Making the correct choice of subsequent career path after fellowship might be a source of stress, but this should allow early-career gastroenterologists to maximize the time spent doing those activities they feel are the most rewarding. A formal mentoring system and an accessible career mentor can be invaluable in allowing the mentee to identify and select that position.

Career fit

The concept of career fit has been described as the ability of individuals to focus their effort on the aspect or aspects of their work that they find most meaningful.5 Multiple specialties have recognized the importance of career fit and the need to choose appropriately when selecting a position and career path upon completing fellowship. In one evaluation of faculty members from the department of medicine at a large academic medical center, those individuals who spent less than 20% of their time working on the activity that they found most meaningful were significantly more likely to demonstrate burnout.5

In a relatively short time period, gastroenterology fellows are required to gather multiple new skill sets, including functioning as a consultant, performing endoscopic procedures, and potentially gaining formal training in clinical, basic, or translational research methods. During this same period, an intense phase of self-assessment should begin, with one critical aim of training being to identify those factors most likely to lead to a long, satisfying career. The growth that occurs during fellowship may allow for the identification of a career track that is likely to be the most rewarding, such as a career as a clinical investigator, clinician educator, or in clinical practice. Importantly, the trainee must decide which career track will most likely lead to self-fulfillment, even if the chosen path does not align with a mentor or advisor. Additionally, self-assessment also may aid in the identification of a niche that an individual finds most intellectually stimulating, which may lead to an area of research or clinical expertise.

While the demonstrated relationship between career fit and burnout is only an association without demonstrated causation, this does merit further consideration. For the first time in most trainees’ careers, the position after fellowship represents an opportunity to choose a job as opposed to going through a “match” process. Therefore, the trainee must strongly consider the factors that will ultimately lead to career satisfaction. If a large disconnect is present between self-identified career goals and the actual tasks required within daily workflow, this may lead to burnout relatively early in a career. Perhaps more importantly, if an individual did not perform adequate self-reflection when choosing a career path or did not receive effective guidance from career mentors, this also might lead to decreased career satisfaction, poor career fit, and an increased risk for burnout as an early-career gastroenterologist.

The mentor’s role

Although a structured career mentoring program is in place within many gastroenterology training programs, other fellowships encourage the mentee to select from a pool of potential mentors. In many cases, trainees and early career gastroenterologists will benefit from building a mentorship team, including career mentor or mentors, research mentors, and other advisors.9

While the mentor-mentee relationship can be an extremely rewarding experience for both parties, the effective mentor must meet a high standard. Several qualities have been identified that will maximize the benefit of the mentor-mentee relationship for the trainee, including the mentor taking a selfless approach to the relationship, working to assist the mentee in choosing a career path that will be the most rewarding, and then aiding the mentee in making helpful connections to promote growth along that chosen path.9 A good mentors should inspire a mentees, but also should be willing to provide honest and at times critical feedback to ensure that mentees maximizes their potential and ultimately assume the appropriate career trajectory. Unbiased mentorship, as well as continued reevaluations of strengths, weaknesses, and career goals by the mentor and mentee, will ultimately offer an opportunity to ensure the best combination of career fit,5 work-life balance,10 and satisfaction with career choice.11

The mentor-mentee relationship after training is complete

Once a trainee has completed gastroenterology fellowship, another stressful transition to the role of an attending physician commences. It is critical that early-career gastroenterologists not only have confidence in the guidance that their mentor has provided to ensure appropriate career fit in their new role but also maintain these critical mentor-mentee relationships during this transition. A good mentor does not disappear because one phase of training is complete. The need for effective mentoring at the junior faculty level also is well recognized,12 and early-career gastroenterologists should continue to rely on established mentoring relationships when new decision points are encountered.

Depending on the career track of an early-career gastroenterologist, formal mentoring also may be offered in the new role as a junior faculty member.12 Additionally, external mentoring can exist within foundations or other subspecialty groups. One example of extramural mentoring is the Career Connection Program offered through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation’s Rising Educators Academics and Clinicians Helping IBD (REACH-IBD) platform. In this program, early-career gastroenterologists are selected and paired with national opinion leaders for one-on-one mentoring relationships. Such a program offers further opportunities for career growth, establishing connections within a smaller subspecialty of gastroenterology, and maximizing career fit.

Conclusion

In an era where the toll of burnout and other influences on early-career gastroenterologists are increasingly being recognized, the importance of career fit during the transition into the role of an attending should not be underestimated. In conjunction with appropriate self-reflection, unbiased and critical mentorship during fellowship can promote significant growth among trainees and allow for the ultimate selection of a career track or career path that will promote happiness, work-life balance, and long-term success as defined by the mentee.

Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, is with the Multidisciplinary Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barnes reports no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Keswani RN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(10):1734-40.

2. Burke C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S593-4.

3. DeCross AJ. AGA Perspectives. 2017.

4. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

5. Shanafelt TD et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):990-5.

6. Ordway SM et al. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(4):347-53.

7. Janko MR, Smeds MR. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1233-42.

8. Eckleberry-Hunt J et al. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-77.

9. Lieberman D. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(1):17-9.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-13.

11. Shanafelt TD et al. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-71.

12. Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1293-7.

Introduction

Burnout in physicians has received significant attention within the past several years, particularly among trainees and early-career physicians. The subspecialties of gastroenterology and hepatology are not immune to burnout, with multiple studies indicating that early career gastroenterologists may be disproportionately affected, compared with their more-established counterparts.1-4 Although the drivers of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment among trainees and early-career gastroenterologists are not fully understood, maximizing career fit during the transition from fellowship into the first posttraining position has been promoted as a potential method to decrease burnout in this population.4,5

While most trainees enter gastroenterology fellowships with a set of predefined career goals, mentorship during fellowship can provide critical guidance along with exposure to new areas and career tracks that were not previously considered. In a survey of gastroenterology and transplant hepatology fellows, 94% of participants with a mentor reported that the mentor significantly influenced their career decision.6 Effective mentoring also has been identified as one possible method to decrease burnout among trainees.7,8

Formal mentoring in gastroenterology fellowship programs might decrease burnout through effectively identifying risk factors such as work hour violations or a lack of social support. Additionally, when fellows are being prepared for transition to their first positions as attending gastroenterologists, there is a critical opportunity to improve career fit and decrease burnout rates among early-career gastroenterologists. Making the correct choice of subsequent career path after fellowship might be a source of stress, but this should allow early-career gastroenterologists to maximize the time spent doing those activities they feel are the most rewarding. A formal mentoring system and an accessible career mentor can be invaluable in allowing the mentee to identify and select that position.

Career fit

The concept of career fit has been described as the ability of individuals to focus their effort on the aspect or aspects of their work that they find most meaningful.5 Multiple specialties have recognized the importance of career fit and the need to choose appropriately when selecting a position and career path upon completing fellowship. In one evaluation of faculty members from the department of medicine at a large academic medical center, those individuals who spent less than 20% of their time working on the activity that they found most meaningful were significantly more likely to demonstrate burnout.5

In a relatively short time period, gastroenterology fellows are required to gather multiple new skill sets, including functioning as a consultant, performing endoscopic procedures, and potentially gaining formal training in clinical, basic, or translational research methods. During this same period, an intense phase of self-assessment should begin, with one critical aim of training being to identify those factors most likely to lead to a long, satisfying career. The growth that occurs during fellowship may allow for the identification of a career track that is likely to be the most rewarding, such as a career as a clinical investigator, clinician educator, or in clinical practice. Importantly, the trainee must decide which career track will most likely lead to self-fulfillment, even if the chosen path does not align with a mentor or advisor. Additionally, self-assessment also may aid in the identification of a niche that an individual finds most intellectually stimulating, which may lead to an area of research or clinical expertise.

While the demonstrated relationship between career fit and burnout is only an association without demonstrated causation, this does merit further consideration. For the first time in most trainees’ careers, the position after fellowship represents an opportunity to choose a job as opposed to going through a “match” process. Therefore, the trainee must strongly consider the factors that will ultimately lead to career satisfaction. If a large disconnect is present between self-identified career goals and the actual tasks required within daily workflow, this may lead to burnout relatively early in a career. Perhaps more importantly, if an individual did not perform adequate self-reflection when choosing a career path or did not receive effective guidance from career mentors, this also might lead to decreased career satisfaction, poor career fit, and an increased risk for burnout as an early-career gastroenterologist.

The mentor’s role

Although a structured career mentoring program is in place within many gastroenterology training programs, other fellowships encourage the mentee to select from a pool of potential mentors. In many cases, trainees and early career gastroenterologists will benefit from building a mentorship team, including career mentor or mentors, research mentors, and other advisors.9

While the mentor-mentee relationship can be an extremely rewarding experience for both parties, the effective mentor must meet a high standard. Several qualities have been identified that will maximize the benefit of the mentor-mentee relationship for the trainee, including the mentor taking a selfless approach to the relationship, working to assist the mentee in choosing a career path that will be the most rewarding, and then aiding the mentee in making helpful connections to promote growth along that chosen path.9 A good mentors should inspire a mentees, but also should be willing to provide honest and at times critical feedback to ensure that mentees maximizes their potential and ultimately assume the appropriate career trajectory. Unbiased mentorship, as well as continued reevaluations of strengths, weaknesses, and career goals by the mentor and mentee, will ultimately offer an opportunity to ensure the best combination of career fit,5 work-life balance,10 and satisfaction with career choice.11

The mentor-mentee relationship after training is complete

Once a trainee has completed gastroenterology fellowship, another stressful transition to the role of an attending physician commences. It is critical that early-career gastroenterologists not only have confidence in the guidance that their mentor has provided to ensure appropriate career fit in their new role but also maintain these critical mentor-mentee relationships during this transition. A good mentor does not disappear because one phase of training is complete. The need for effective mentoring at the junior faculty level also is well recognized,12 and early-career gastroenterologists should continue to rely on established mentoring relationships when new decision points are encountered.

Depending on the career track of an early-career gastroenterologist, formal mentoring also may be offered in the new role as a junior faculty member.12 Additionally, external mentoring can exist within foundations or other subspecialty groups. One example of extramural mentoring is the Career Connection Program offered through the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation’s Rising Educators Academics and Clinicians Helping IBD (REACH-IBD) platform. In this program, early-career gastroenterologists are selected and paired with national opinion leaders for one-on-one mentoring relationships. Such a program offers further opportunities for career growth, establishing connections within a smaller subspecialty of gastroenterology, and maximizing career fit.

Conclusion

In an era where the toll of burnout and other influences on early-career gastroenterologists are increasingly being recognized, the importance of career fit during the transition into the role of an attending should not be underestimated. In conjunction with appropriate self-reflection, unbiased and critical mentorship during fellowship can promote significant growth among trainees and allow for the ultimate selection of a career track or career path that will promote happiness, work-life balance, and long-term success as defined by the mentee.

Edward L. Barnes, MD, MPH, is with the Multidisciplinary Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barnes reports no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Keswani RN et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(10):1734-40.

2. Burke C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S593-4.

3. DeCross AJ. AGA Perspectives. 2017.

4. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

5. Shanafelt TD et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):990-5.

6. Ordway SM et al. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(4):347-53.

7. Janko MR, Smeds MR. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69(4):1233-42.

8. Eckleberry-Hunt J et al. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-77.

9. Lieberman D. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(1):17-9.

10. Shanafelt TD et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-13.

11. Shanafelt TD et al. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463-71.

12. Shaheen NJ, Sandler RS. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1293-7.

Introduction

Burnout in physicians has received significant attention within the past several years, particularly among trainees and early-career physicians. The subspecialties of gastroenterology and hepatology are not immune to burnout, with multiple studies indicating that early career gastroenterologists may be disproportionately affected, compared with their more-established counterparts.1-4 Although the drivers of depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment among trainees and early-career gastroenterologists are not fully understood, maximizing career fit during the transition from fellowship into the first posttraining position has been promoted as a potential method to decrease burnout in this population.4,5

While most trainees enter gastroenterology fellowships with a set of predefined career goals, mentorship during fellowship can provide critical guidance along with exposure to new areas and career tracks that were not previously considered. In a survey of gastroenterology and transplant hepatology fellows, 94% of participants with a mentor reported that the mentor significantly influenced their career decision.6 Effective mentoring also has been identified as one possible method to decrease burnout among trainees.7,8

Formal mentoring in gastroenterology fellowship programs might decrease burnout through effectively identifying risk factors such as work hour violations or a lack of social support. Additionally, when fellows are being prepared for transition to their first positions as attending gastroenterologists, there is a critical opportunity to improve career fit and decrease burnout rates among early-career gastroenterologists. Making the correct choice of subsequent career path after fellowship might be a source of stress, but this should allow early-career gastroenterologists to maximize the time spent doing those activities they feel are the most rewarding. A formal mentoring system and an accessible career mentor can be invaluable in allowing the mentee to identify and select that position.

Career fit