User login

Neurology’s seasonal disease prevalences

Neurology, like most of medicine, has different disease prevalences as the seasons change.

In Phoenix, for example, July-August is migraine season. When the monsoons roll in the afternoon several times a week, my office phones ring merrily with requests for early triptan refills and medication changes.

In December, you may think of Hanukkah, Christmas, eggnog, gifts, latkes ... but at my office I think of seizures.

The calls start around Thanksgiving and continue until after New Years. Breakthrough seizures become common. People travel and leave their pills at home (calling scrips to out-of-state pharmacies is a holiday ritual here). They go to parties and are up late, and forget to take their pills. Or simply the combination of more frequent alcohol use, holiday stress, and sleep deprivation does the trick.

This time of year, with kids out on breaks, family trips, visiting relatives, parties, and shopping, always makes those "well, you’ll have to stop driving until ..." discussions even uglier.

After years of experience, I try to warn people in advance. At routine appointments I tell them that the holiday spirit (or spirits) aren’t conducive to medication compliance and discuss ways of remembering to take pills. Usually it works, but there is always someone caught up in the season of travel, sleep deprivation, and stress who forgets.

And so, as the (not particularly cold) Phoenix winter comes, my staff and I prepare for neurology’s peculiar rite of winter.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Neurology, like most of medicine, has different disease prevalences as the seasons change.

In Phoenix, for example, July-August is migraine season. When the monsoons roll in the afternoon several times a week, my office phones ring merrily with requests for early triptan refills and medication changes.

In December, you may think of Hanukkah, Christmas, eggnog, gifts, latkes ... but at my office I think of seizures.

The calls start around Thanksgiving and continue until after New Years. Breakthrough seizures become common. People travel and leave their pills at home (calling scrips to out-of-state pharmacies is a holiday ritual here). They go to parties and are up late, and forget to take their pills. Or simply the combination of more frequent alcohol use, holiday stress, and sleep deprivation does the trick.

This time of year, with kids out on breaks, family trips, visiting relatives, parties, and shopping, always makes those "well, you’ll have to stop driving until ..." discussions even uglier.

After years of experience, I try to warn people in advance. At routine appointments I tell them that the holiday spirit (or spirits) aren’t conducive to medication compliance and discuss ways of remembering to take pills. Usually it works, but there is always someone caught up in the season of travel, sleep deprivation, and stress who forgets.

And so, as the (not particularly cold) Phoenix winter comes, my staff and I prepare for neurology’s peculiar rite of winter.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Neurology, like most of medicine, has different disease prevalences as the seasons change.

In Phoenix, for example, July-August is migraine season. When the monsoons roll in the afternoon several times a week, my office phones ring merrily with requests for early triptan refills and medication changes.

In December, you may think of Hanukkah, Christmas, eggnog, gifts, latkes ... but at my office I think of seizures.

The calls start around Thanksgiving and continue until after New Years. Breakthrough seizures become common. People travel and leave their pills at home (calling scrips to out-of-state pharmacies is a holiday ritual here). They go to parties and are up late, and forget to take their pills. Or simply the combination of more frequent alcohol use, holiday stress, and sleep deprivation does the trick.

This time of year, with kids out on breaks, family trips, visiting relatives, parties, and shopping, always makes those "well, you’ll have to stop driving until ..." discussions even uglier.

After years of experience, I try to warn people in advance. At routine appointments I tell them that the holiday spirit (or spirits) aren’t conducive to medication compliance and discuss ways of remembering to take pills. Usually it works, but there is always someone caught up in the season of travel, sleep deprivation, and stress who forgets.

And so, as the (not particularly cold) Phoenix winter comes, my staff and I prepare for neurology’s peculiar rite of winter.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

When carrying less is carrying more

On a recent visit to a medical school, I watched the usual parade of residents and medical students go by in the typical flock of white coats on rounds. Been there, done that.

But what surprised me was how little they carried (which you’d think I’d be used to). When I was a medical student, my pockets were crammed full of books:

• A pocket pharmacopoeia.

• Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics.

• An antibiotic use pamphlet.

• Handbook of Radiology.

• The House Officer’s Guide.

• On Call Reference.

I think a reason most medical students were so thin (besides living on ramen, tuna, and coffee) is the exercise we’d get wearing a coat that weighed more than we did. Not to mention the clipboard I carried everywhere to frantically scribble notes, reminders, and clinical pearls on.

But those aren’t necessary any more. Now that world-changing invention, the smartphone, has replaced all. In just 5 ounces of metal and glass you have all these books, and more. Questions you don’t know can be Googled (provided the attending doesn’t see you). Notes and reminders can be typed on the fly. Medical students may not get as much exercise on rounds, but on the other hand, they are less likely to suffer back injuries.

I’m not whining about this at all. I’m quite fond of it. Even as an attending, it’s much easier to have all my references in one convenient place. The Physicians’ Desk Reference is likely the biggest and heaviest book in medicine, and it’s nice to be rid of it – not to mention all the trees we’re saving by using the electronic gadgets.

Now I just need to find another way to exercise.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

On a recent visit to a medical school, I watched the usual parade of residents and medical students go by in the typical flock of white coats on rounds. Been there, done that.

But what surprised me was how little they carried (which you’d think I’d be used to). When I was a medical student, my pockets were crammed full of books:

• A pocket pharmacopoeia.

• Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics.

• An antibiotic use pamphlet.

• Handbook of Radiology.

• The House Officer’s Guide.

• On Call Reference.

I think a reason most medical students were so thin (besides living on ramen, tuna, and coffee) is the exercise we’d get wearing a coat that weighed more than we did. Not to mention the clipboard I carried everywhere to frantically scribble notes, reminders, and clinical pearls on.

But those aren’t necessary any more. Now that world-changing invention, the smartphone, has replaced all. In just 5 ounces of metal and glass you have all these books, and more. Questions you don’t know can be Googled (provided the attending doesn’t see you). Notes and reminders can be typed on the fly. Medical students may not get as much exercise on rounds, but on the other hand, they are less likely to suffer back injuries.

I’m not whining about this at all. I’m quite fond of it. Even as an attending, it’s much easier to have all my references in one convenient place. The Physicians’ Desk Reference is likely the biggest and heaviest book in medicine, and it’s nice to be rid of it – not to mention all the trees we’re saving by using the electronic gadgets.

Now I just need to find another way to exercise.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

On a recent visit to a medical school, I watched the usual parade of residents and medical students go by in the typical flock of white coats on rounds. Been there, done that.

But what surprised me was how little they carried (which you’d think I’d be used to). When I was a medical student, my pockets were crammed full of books:

• A pocket pharmacopoeia.

• Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics.

• An antibiotic use pamphlet.

• Handbook of Radiology.

• The House Officer’s Guide.

• On Call Reference.

I think a reason most medical students were so thin (besides living on ramen, tuna, and coffee) is the exercise we’d get wearing a coat that weighed more than we did. Not to mention the clipboard I carried everywhere to frantically scribble notes, reminders, and clinical pearls on.

But those aren’t necessary any more. Now that world-changing invention, the smartphone, has replaced all. In just 5 ounces of metal and glass you have all these books, and more. Questions you don’t know can be Googled (provided the attending doesn’t see you). Notes and reminders can be typed on the fly. Medical students may not get as much exercise on rounds, but on the other hand, they are less likely to suffer back injuries.

I’m not whining about this at all. I’m quite fond of it. Even as an attending, it’s much easier to have all my references in one convenient place. The Physicians’ Desk Reference is likely the biggest and heaviest book in medicine, and it’s nice to be rid of it – not to mention all the trees we’re saving by using the electronic gadgets.

Now I just need to find another way to exercise.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Accepting the bad with the good in U.S. medicine

I like it here. I’m not saying America, Arizona, or Americans are perfect – far from it. But realistically, there’s no country on Earth that is. I was born here, and I like my practice.

Occasionally, I get letters from companies suggesting I relocate overseas to "doctor-friendly" countries. They claim to offer better salaries, better lifestyles, etc. They also suggest that my patients will follow me for medical tourism.

I have nothing against physicians who move. Some jobs certainly aren’t worth staying for, or there are family reasons, or whatever. But I have no desire to move to a different country.

One of my favorite books is "I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew" by Dr. Seuss. In it, the hero keeps trying to find a place that has no troubles, only to discover that everywhere he goes has its own set of problems, just different from the previous place. So, at the end, he returns home. He realizes that every place has good and bad, and it’s a question of accepting the bad parts and doing your best to deal with them.

For myself, I’m happy where I am. I have no interest in moving to another country in search of Solla Sollew. Dr. Seuss told me it doesn’t exist, and life has proven him correct.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I like it here. I’m not saying America, Arizona, or Americans are perfect – far from it. But realistically, there’s no country on Earth that is. I was born here, and I like my practice.

Occasionally, I get letters from companies suggesting I relocate overseas to "doctor-friendly" countries. They claim to offer better salaries, better lifestyles, etc. They also suggest that my patients will follow me for medical tourism.

I have nothing against physicians who move. Some jobs certainly aren’t worth staying for, or there are family reasons, or whatever. But I have no desire to move to a different country.

One of my favorite books is "I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew" by Dr. Seuss. In it, the hero keeps trying to find a place that has no troubles, only to discover that everywhere he goes has its own set of problems, just different from the previous place. So, at the end, he returns home. He realizes that every place has good and bad, and it’s a question of accepting the bad parts and doing your best to deal with them.

For myself, I’m happy where I am. I have no interest in moving to another country in search of Solla Sollew. Dr. Seuss told me it doesn’t exist, and life has proven him correct.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I like it here. I’m not saying America, Arizona, or Americans are perfect – far from it. But realistically, there’s no country on Earth that is. I was born here, and I like my practice.

Occasionally, I get letters from companies suggesting I relocate overseas to "doctor-friendly" countries. They claim to offer better salaries, better lifestyles, etc. They also suggest that my patients will follow me for medical tourism.

I have nothing against physicians who move. Some jobs certainly aren’t worth staying for, or there are family reasons, or whatever. But I have no desire to move to a different country.

One of my favorite books is "I Had Trouble in Getting to Solla Sollew" by Dr. Seuss. In it, the hero keeps trying to find a place that has no troubles, only to discover that everywhere he goes has its own set of problems, just different from the previous place. So, at the end, he returns home. He realizes that every place has good and bad, and it’s a question of accepting the bad parts and doing your best to deal with them.

For myself, I’m happy where I am. I have no interest in moving to another country in search of Solla Sollew. Dr. Seuss told me it doesn’t exist, and life has proven him correct.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One wave of my magic wand and it will all feel better

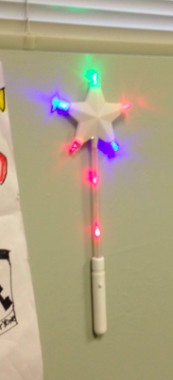

At a carnival last year, my kids won a magic wand and gave it to me.

For a while it sat on a bookshelf at home, along with a clay snowman and decorated picture frame they’d given me. It was one of those things that I had no idea what to do with, but was afraid to get rid of for fear of hurting their feelings.

About a month later, I was dealing with a young lady who wanted me to make her better, but didn’t want to take any medications or try treatment of any sort. In her own words, she "just wanted to get fixed." (Fortunately for her, I’m not a veterinarian.)

She left my office, with both of us frustrated – I, because she wouldn’t let me help her, and she, because in her mind I couldn’t offer her what she wanted: a magic cure.

That evening, it occurred to me that she would have been the perfect subject for my magic wand. The next morning I hung it up in my office, where it’s remained since.

It even lights up when I press the button.

So now, I have a treatment option. At no additional charge and covered by all insurance plans, I wave a magic wand. Granted, it has absolutely no capabilities to evaluate or treat, but it often gets my point across.

Now, when people want me to figure things out without doing tests, or want me to make them better without medication or physical therapy, I offer them the wand. Initially, I was afraid it would make people angry, but have since found it surprisingly effective at getting my point across: There is no magic in medicine, and I need their help to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

At a carnival last year, my kids won a magic wand and gave it to me.

For a while it sat on a bookshelf at home, along with a clay snowman and decorated picture frame they’d given me. It was one of those things that I had no idea what to do with, but was afraid to get rid of for fear of hurting their feelings.

About a month later, I was dealing with a young lady who wanted me to make her better, but didn’t want to take any medications or try treatment of any sort. In her own words, she "just wanted to get fixed." (Fortunately for her, I’m not a veterinarian.)

She left my office, with both of us frustrated – I, because she wouldn’t let me help her, and she, because in her mind I couldn’t offer her what she wanted: a magic cure.

That evening, it occurred to me that she would have been the perfect subject for my magic wand. The next morning I hung it up in my office, where it’s remained since.

It even lights up when I press the button.

So now, I have a treatment option. At no additional charge and covered by all insurance plans, I wave a magic wand. Granted, it has absolutely no capabilities to evaluate or treat, but it often gets my point across.

Now, when people want me to figure things out without doing tests, or want me to make them better without medication or physical therapy, I offer them the wand. Initially, I was afraid it would make people angry, but have since found it surprisingly effective at getting my point across: There is no magic in medicine, and I need their help to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

At a carnival last year, my kids won a magic wand and gave it to me.

For a while it sat on a bookshelf at home, along with a clay snowman and decorated picture frame they’d given me. It was one of those things that I had no idea what to do with, but was afraid to get rid of for fear of hurting their feelings.

About a month later, I was dealing with a young lady who wanted me to make her better, but didn’t want to take any medications or try treatment of any sort. In her own words, she "just wanted to get fixed." (Fortunately for her, I’m not a veterinarian.)

She left my office, with both of us frustrated – I, because she wouldn’t let me help her, and she, because in her mind I couldn’t offer her what she wanted: a magic cure.

That evening, it occurred to me that she would have been the perfect subject for my magic wand. The next morning I hung it up in my office, where it’s remained since.

It even lights up when I press the button.

So now, I have a treatment option. At no additional charge and covered by all insurance plans, I wave a magic wand. Granted, it has absolutely no capabilities to evaluate or treat, but it often gets my point across.

Now, when people want me to figure things out without doing tests, or want me to make them better without medication or physical therapy, I offer them the wand. Initially, I was afraid it would make people angry, but have since found it surprisingly effective at getting my point across: There is no magic in medicine, and I need their help to help them.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The centerpiece of my new office

I have a new desk.

In April, I moved offices for the first time in my career. My last office was small, having previously been subleased as a satellite office by the group I started with. When they shut down operations and I stayed, I took it over. This included a small, basic desk. It was nothing fancy, a pressboard student desk.

In the late 1960s, my dad was starting his law practice, and bought a HUGE desk. It was top of the line and cost a few hundred dollars then (no idea what it would be now) – more than he could afford – but he knew it would be the centerpiece for his law practice. So he bought it.

He practiced law for almost 40 years at the desk, and then put it in storage for me. I always wanted to use it, but my last office was too small. The desk was too big for the 9-by-9 room I spent almost 15 years working out of.

So when I moved, a room big enough for me and this desk was a key requirement. It was a joy to set it up finally. It even has my dad’s old markings on the bottom to show where to put the screws during assembly. It has eight enormous drawers and a beautiful curved top. The center is darker where his leather blotter covered it for 40 years.

My dad got to see the desk only once in my office, and he was pleased to see it in its second life. With him now gone, my daily time spent at it, although still filled with everyday work, is somehow more special. It is a connection between us. I think of all the hours he put in at it to support his family and am happy to be using it now for mine.

Thank you, dad.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I have a new desk.

In April, I moved offices for the first time in my career. My last office was small, having previously been subleased as a satellite office by the group I started with. When they shut down operations and I stayed, I took it over. This included a small, basic desk. It was nothing fancy, a pressboard student desk.

In the late 1960s, my dad was starting his law practice, and bought a HUGE desk. It was top of the line and cost a few hundred dollars then (no idea what it would be now) – more than he could afford – but he knew it would be the centerpiece for his law practice. So he bought it.

He practiced law for almost 40 years at the desk, and then put it in storage for me. I always wanted to use it, but my last office was too small. The desk was too big for the 9-by-9 room I spent almost 15 years working out of.

So when I moved, a room big enough for me and this desk was a key requirement. It was a joy to set it up finally. It even has my dad’s old markings on the bottom to show where to put the screws during assembly. It has eight enormous drawers and a beautiful curved top. The center is darker where his leather blotter covered it for 40 years.

My dad got to see the desk only once in my office, and he was pleased to see it in its second life. With him now gone, my daily time spent at it, although still filled with everyday work, is somehow more special. It is a connection between us. I think of all the hours he put in at it to support his family and am happy to be using it now for mine.

Thank you, dad.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I have a new desk.

In April, I moved offices for the first time in my career. My last office was small, having previously been subleased as a satellite office by the group I started with. When they shut down operations and I stayed, I took it over. This included a small, basic desk. It was nothing fancy, a pressboard student desk.

In the late 1960s, my dad was starting his law practice, and bought a HUGE desk. It was top of the line and cost a few hundred dollars then (no idea what it would be now) – more than he could afford – but he knew it would be the centerpiece for his law practice. So he bought it.

He practiced law for almost 40 years at the desk, and then put it in storage for me. I always wanted to use it, but my last office was too small. The desk was too big for the 9-by-9 room I spent almost 15 years working out of.

So when I moved, a room big enough for me and this desk was a key requirement. It was a joy to set it up finally. It even has my dad’s old markings on the bottom to show where to put the screws during assembly. It has eight enormous drawers and a beautiful curved top. The center is darker where his leather blotter covered it for 40 years.

My dad got to see the desk only once in my office, and he was pleased to see it in its second life. With him now gone, my daily time spent at it, although still filled with everyday work, is somehow more special. It is a connection between us. I think of all the hours he put in at it to support his family and am happy to be using it now for mine.

Thank you, dad.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Finding the time to do CME

CME drives me nuts. Yes, I know it’s the rules, and the whole idea is to make sure we all keep current on our knowledge, but it’s still a pain in the butt.

I try to do mine in the cracks of everyday life. In solo practice, I don’t have time to go to meetings. So I do all mine on paper or online. My usual method is summer vacation. We go on long driving trips. Since my wife prefers to drive, I just hunker down in my seat with a pile of CME monographs and work my way through them bit by bit.

This year, we didn’t go on a trip, so I’m stuck working it in on weekends and evenings.

I’m sure there’s a better way to do this, but I have no clue what it is. So I take my pile of papers and iPad with me wherever I go, reading things and marking off answers.

I understand the idea behind it. No one wants a doctor with a wealth of experience but a paucity of modern knowledge. Medicine is (and always will be) a changing field. No one can keep up on it entirely. So this is how we’re supposed to prove that we’re trying. How well does it work? I have no idea. Apparently no one has found a better way to do it, though.

So I dutifully do my reading and fill in the circles on the answer sheet because I have to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

CME drives me nuts. Yes, I know it’s the rules, and the whole idea is to make sure we all keep current on our knowledge, but it’s still a pain in the butt.

I try to do mine in the cracks of everyday life. In solo practice, I don’t have time to go to meetings. So I do all mine on paper or online. My usual method is summer vacation. We go on long driving trips. Since my wife prefers to drive, I just hunker down in my seat with a pile of CME monographs and work my way through them bit by bit.

This year, we didn’t go on a trip, so I’m stuck working it in on weekends and evenings.

I’m sure there’s a better way to do this, but I have no clue what it is. So I take my pile of papers and iPad with me wherever I go, reading things and marking off answers.

I understand the idea behind it. No one wants a doctor with a wealth of experience but a paucity of modern knowledge. Medicine is (and always will be) a changing field. No one can keep up on it entirely. So this is how we’re supposed to prove that we’re trying. How well does it work? I have no idea. Apparently no one has found a better way to do it, though.

So I dutifully do my reading and fill in the circles on the answer sheet because I have to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

CME drives me nuts. Yes, I know it’s the rules, and the whole idea is to make sure we all keep current on our knowledge, but it’s still a pain in the butt.

I try to do mine in the cracks of everyday life. In solo practice, I don’t have time to go to meetings. So I do all mine on paper or online. My usual method is summer vacation. We go on long driving trips. Since my wife prefers to drive, I just hunker down in my seat with a pile of CME monographs and work my way through them bit by bit.

This year, we didn’t go on a trip, so I’m stuck working it in on weekends and evenings.

I’m sure there’s a better way to do this, but I have no clue what it is. So I take my pile of papers and iPad with me wherever I go, reading things and marking off answers.

I understand the idea behind it. No one wants a doctor with a wealth of experience but a paucity of modern knowledge. Medicine is (and always will be) a changing field. No one can keep up on it entirely. So this is how we’re supposed to prove that we’re trying. How well does it work? I have no idea. Apparently no one has found a better way to do it, though.

So I dutifully do my reading and fill in the circles on the answer sheet because I have to.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Why I’m happy my kids don’t want to be doctors

Right now my oldest child wants to be an inventor, my next wants to be a teacher, and my last isn’t sure. Granted, they all have a lot of time to decide.

None of them wants to be a doctor. I’m glad.

In seventh grade, I had to interview someone about their job. Like most kids, I picked my dad. He was a lawyer, and so we chatted about his field while a cassette tape slowly turned. At one point, I asked him if he’d recommend law to others, and he said, to my surprise, "no." He elaborated by saying that the field had changed so much since he’d started that he didn’t feel it was a rewarding career anymore.

It’s been 35 years since then, and now I feel the same way.

I once loved medicine. In the idealism of youth, I viewed it as a calling, a chance to help and make a difference in the lives of others. To a large extent, I still feel that way. I like what I do, even though time and reality have dimmed the fires.

But would I recommend this to anyone else? No.

Like Dad said a long time ago, things have changed. I wouldn’t want to walk out of medical school $200,000 (or more) in debt. That puts such a huge shadow over your future – I don’t see it as being worthwhile. I didn’t become a doctor to get rich, but starting out behind the eight-ball is never good.

Medicine isn’t the same. We’re not the old family docs of yore. Our cause is still just, but we’re often vilified for political or legal expediency – or profit. People who know nothing about medicine try to tell us what we can or can’t do. We get stuck in the middle of battles we never wanted to be a part of. Internet and television charlatans are treated like miracle workers.

Through it all, most of us try to do our best for our patients. But over time, it’s the other things that whittle you down. It’s those reasons that make me glad none of my kids is currently interested in doing this job.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Right now my oldest child wants to be an inventor, my next wants to be a teacher, and my last isn’t sure. Granted, they all have a lot of time to decide.

None of them wants to be a doctor. I’m glad.

In seventh grade, I had to interview someone about their job. Like most kids, I picked my dad. He was a lawyer, and so we chatted about his field while a cassette tape slowly turned. At one point, I asked him if he’d recommend law to others, and he said, to my surprise, "no." He elaborated by saying that the field had changed so much since he’d started that he didn’t feel it was a rewarding career anymore.

It’s been 35 years since then, and now I feel the same way.

I once loved medicine. In the idealism of youth, I viewed it as a calling, a chance to help and make a difference in the lives of others. To a large extent, I still feel that way. I like what I do, even though time and reality have dimmed the fires.

But would I recommend this to anyone else? No.

Like Dad said a long time ago, things have changed. I wouldn’t want to walk out of medical school $200,000 (or more) in debt. That puts such a huge shadow over your future – I don’t see it as being worthwhile. I didn’t become a doctor to get rich, but starting out behind the eight-ball is never good.

Medicine isn’t the same. We’re not the old family docs of yore. Our cause is still just, but we’re often vilified for political or legal expediency – or profit. People who know nothing about medicine try to tell us what we can or can’t do. We get stuck in the middle of battles we never wanted to be a part of. Internet and television charlatans are treated like miracle workers.

Through it all, most of us try to do our best for our patients. But over time, it’s the other things that whittle you down. It’s those reasons that make me glad none of my kids is currently interested in doing this job.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Right now my oldest child wants to be an inventor, my next wants to be a teacher, and my last isn’t sure. Granted, they all have a lot of time to decide.

None of them wants to be a doctor. I’m glad.

In seventh grade, I had to interview someone about their job. Like most kids, I picked my dad. He was a lawyer, and so we chatted about his field while a cassette tape slowly turned. At one point, I asked him if he’d recommend law to others, and he said, to my surprise, "no." He elaborated by saying that the field had changed so much since he’d started that he didn’t feel it was a rewarding career anymore.

It’s been 35 years since then, and now I feel the same way.

I once loved medicine. In the idealism of youth, I viewed it as a calling, a chance to help and make a difference in the lives of others. To a large extent, I still feel that way. I like what I do, even though time and reality have dimmed the fires.

But would I recommend this to anyone else? No.

Like Dad said a long time ago, things have changed. I wouldn’t want to walk out of medical school $200,000 (or more) in debt. That puts such a huge shadow over your future – I don’t see it as being worthwhile. I didn’t become a doctor to get rich, but starting out behind the eight-ball is never good.

Medicine isn’t the same. We’re not the old family docs of yore. Our cause is still just, but we’re often vilified for political or legal expediency – or profit. People who know nothing about medicine try to tell us what we can or can’t do. We get stuck in the middle of battles we never wanted to be a part of. Internet and television charlatans are treated like miracle workers.

Through it all, most of us try to do our best for our patients. But over time, it’s the other things that whittle you down. It’s those reasons that make me glad none of my kids is currently interested in doing this job.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The doctor’s office is not a playground

One of the most infuriating things in a medical practice (or probably anywhere) is when people don’t supervise their kids.

I have nothing against kids. I’m not a pediatrician, but that’s more of a personality thing.

Like any adult neurologist, I don’t see kids, and my office isn’t set up for them. Most parents are aware of this. They either don’t bring them, or when unavoidable, bring stuff to keep them busy: Nintendos, books, iPhone games, etc.

But some assume my office is a day care, and this is a serious problem. I have no idea if my colleagues down the street at the Mayo Clinic have to put up with shenanigans like this, but unfortunately in a typical office practice, it happens too often.

If I step out of the office for something, I’ve had parents do things like handing my examining tools (including fragile things like an ophthalmoscope) to their children to play with or let them look through my desk drawers. Others have allowed their children to randomly run through the halls of my office or even ask my secretary if they can sit at her desk so she can keep them busy. After all, she has a computer. Why can’t their kids play on it? Never mind that she’s constantly scheduling or looking up charts with it.

These same parents also get irate when told no, or are asked to control their kids. I’ve been accused of hating children, being unreasonable, and being unaccommodating.

I’m not in the habit of disciplining other people’s kids. I don’t want someone to do it to mine, and I won’t do it to theirs. In the rare cases when a kid’s behavior makes a visit impossible, I’ve asked people to leave. There are even some patients who I’ve told not to return unless they don’t bring their kids.

Inevitably, this has cost me a few patients and probably gotten me a few bad reviews online. But I really don’t care. Good patient care, not to mention sanity, requires as few distractions as possible. And if I can’t practice good patient care, what’s the point of wasting the patient’s and my own time?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One of the most infuriating things in a medical practice (or probably anywhere) is when people don’t supervise their kids.

I have nothing against kids. I’m not a pediatrician, but that’s more of a personality thing.

Like any adult neurologist, I don’t see kids, and my office isn’t set up for them. Most parents are aware of this. They either don’t bring them, or when unavoidable, bring stuff to keep them busy: Nintendos, books, iPhone games, etc.

But some assume my office is a day care, and this is a serious problem. I have no idea if my colleagues down the street at the Mayo Clinic have to put up with shenanigans like this, but unfortunately in a typical office practice, it happens too often.

If I step out of the office for something, I’ve had parents do things like handing my examining tools (including fragile things like an ophthalmoscope) to their children to play with or let them look through my desk drawers. Others have allowed their children to randomly run through the halls of my office or even ask my secretary if they can sit at her desk so she can keep them busy. After all, she has a computer. Why can’t their kids play on it? Never mind that she’s constantly scheduling or looking up charts with it.

These same parents also get irate when told no, or are asked to control their kids. I’ve been accused of hating children, being unreasonable, and being unaccommodating.

I’m not in the habit of disciplining other people’s kids. I don’t want someone to do it to mine, and I won’t do it to theirs. In the rare cases when a kid’s behavior makes a visit impossible, I’ve asked people to leave. There are even some patients who I’ve told not to return unless they don’t bring their kids.

Inevitably, this has cost me a few patients and probably gotten me a few bad reviews online. But I really don’t care. Good patient care, not to mention sanity, requires as few distractions as possible. And if I can’t practice good patient care, what’s the point of wasting the patient’s and my own time?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One of the most infuriating things in a medical practice (or probably anywhere) is when people don’t supervise their kids.

I have nothing against kids. I’m not a pediatrician, but that’s more of a personality thing.

Like any adult neurologist, I don’t see kids, and my office isn’t set up for them. Most parents are aware of this. They either don’t bring them, or when unavoidable, bring stuff to keep them busy: Nintendos, books, iPhone games, etc.

But some assume my office is a day care, and this is a serious problem. I have no idea if my colleagues down the street at the Mayo Clinic have to put up with shenanigans like this, but unfortunately in a typical office practice, it happens too often.

If I step out of the office for something, I’ve had parents do things like handing my examining tools (including fragile things like an ophthalmoscope) to their children to play with or let them look through my desk drawers. Others have allowed their children to randomly run through the halls of my office or even ask my secretary if they can sit at her desk so she can keep them busy. After all, she has a computer. Why can’t their kids play on it? Never mind that she’s constantly scheduling or looking up charts with it.

These same parents also get irate when told no, or are asked to control their kids. I’ve been accused of hating children, being unreasonable, and being unaccommodating.

I’m not in the habit of disciplining other people’s kids. I don’t want someone to do it to mine, and I won’t do it to theirs. In the rare cases when a kid’s behavior makes a visit impossible, I’ve asked people to leave. There are even some patients who I’ve told not to return unless they don’t bring their kids.

Inevitably, this has cost me a few patients and probably gotten me a few bad reviews online. But I really don’t care. Good patient care, not to mention sanity, requires as few distractions as possible. And if I can’t practice good patient care, what’s the point of wasting the patient’s and my own time?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The fading appeal of grand rounds

Does anyone else out there go to grand rounds? I don’t either.

I’m sure this is still a cherished tradition at academic places. But in the real world of private practice, it’s not.

That’s not to say my nonteaching hospital doesn’t still have them. Occasionally, I see a notice up for some sort of educational gathering. I scan it, but really have no interest in going. Even the opportunity for an hour of free CME doesn’t entice me.

Realistically, I’d rather be at my office, working. An hour spent in a lecture hall is 1 hour more of work I need to do after I get back.

In medical school and residency, you went. You didn’t have a choice. There was always some eagle-eyed attending physician scanning the crowd, making mental notes on who was or wasn’t there. (Yes, Bill and Larry, I’m talking about you.)

I’m not sure I ever got anything out of it, besides coffee and a bagel. In my experience, a lot of it was on some esoteric research that didn’t have any immediately practical applications. There were, of course, exceptions. Sometimes there’d be a good review of a disorder and its treatments that was helpful, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Usually, I just nodded off in the back. Rarely, I’d make my pager chirp, look at it, and leave. (This was such a common trick for everyone that you couldn’t do it too often.)

These days, I find it easier to handpick my own learning material, usually on an iPad, and learn it on my own schedule. This way it’s more relevant and useful to me. And in private practice, that’s what’s important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Does anyone else out there go to grand rounds? I don’t either.

I’m sure this is still a cherished tradition at academic places. But in the real world of private practice, it’s not.

That’s not to say my nonteaching hospital doesn’t still have them. Occasionally, I see a notice up for some sort of educational gathering. I scan it, but really have no interest in going. Even the opportunity for an hour of free CME doesn’t entice me.

Realistically, I’d rather be at my office, working. An hour spent in a lecture hall is 1 hour more of work I need to do after I get back.

In medical school and residency, you went. You didn’t have a choice. There was always some eagle-eyed attending physician scanning the crowd, making mental notes on who was or wasn’t there. (Yes, Bill and Larry, I’m talking about you.)

I’m not sure I ever got anything out of it, besides coffee and a bagel. In my experience, a lot of it was on some esoteric research that didn’t have any immediately practical applications. There were, of course, exceptions. Sometimes there’d be a good review of a disorder and its treatments that was helpful, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Usually, I just nodded off in the back. Rarely, I’d make my pager chirp, look at it, and leave. (This was such a common trick for everyone that you couldn’t do it too often.)

These days, I find it easier to handpick my own learning material, usually on an iPad, and learn it on my own schedule. This way it’s more relevant and useful to me. And in private practice, that’s what’s important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Does anyone else out there go to grand rounds? I don’t either.

I’m sure this is still a cherished tradition at academic places. But in the real world of private practice, it’s not.

That’s not to say my nonteaching hospital doesn’t still have them. Occasionally, I see a notice up for some sort of educational gathering. I scan it, but really have no interest in going. Even the opportunity for an hour of free CME doesn’t entice me.

Realistically, I’d rather be at my office, working. An hour spent in a lecture hall is 1 hour more of work I need to do after I get back.

In medical school and residency, you went. You didn’t have a choice. There was always some eagle-eyed attending physician scanning the crowd, making mental notes on who was or wasn’t there. (Yes, Bill and Larry, I’m talking about you.)

I’m not sure I ever got anything out of it, besides coffee and a bagel. In my experience, a lot of it was on some esoteric research that didn’t have any immediately practical applications. There were, of course, exceptions. Sometimes there’d be a good review of a disorder and its treatments that was helpful, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Usually, I just nodded off in the back. Rarely, I’d make my pager chirp, look at it, and leave. (This was such a common trick for everyone that you couldn’t do it too often.)

These days, I find it easier to handpick my own learning material, usually on an iPad, and learn it on my own schedule. This way it’s more relevant and useful to me. And in private practice, that’s what’s important.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Higher pay for work outside of patient care undermines priorities

Finances are a big part of our lives. We may have become doctors to help people, but we're also supporting families.

The main job, for most of us, is to take care of patients. That's allegedly what we're most appreciated for, so shouldn't it be what pays the bills?

Patient care is still my bread and butter, but here are some dollar figures to think about:

(The following averages are NOT any sort of scientific data. They're based on my own experiences and phone calls to other neurologists.)

- Speaking for a drug company: $750 per hour.

- Legal work: $400 per hour.

- Clinical trials research: $350 per hour.

- Market research: $250 per hour.

- Actually caring for patients: $100 per hour (real money, not the amounts we charge insurance companies, knowing we'll never collect them).

I know that many nondoctors will look at the above and say, "$100 per hour sounds great! These docs should shut up and take it!" Those people, however, are not in the position of also having to pay for rent, malpractice insurance, staff salaries, office supplies, and student loans, each at five to six figures per year.

Do the priorities on this list seem screwed up to anyone else out there? Obviously, clinical research for future medications is important, but does it seem odd that I can make more money for legal work or market research than, say, directly helping people?

You bet. But they do pay more, and so many of us are rapidly gravitating to them as supplemental income. The economics don't give us many other choices. If we want to help patients, we have to be able to keep our practices open.

I think this is sad because, when we all started out applying to medical school, most of us just wanted to care for people. But these days that's the least valued thing we do.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Finances are a big part of our lives. We may have become doctors to help people, but we're also supporting families.

The main job, for most of us, is to take care of patients. That's allegedly what we're most appreciated for, so shouldn't it be what pays the bills?

Patient care is still my bread and butter, but here are some dollar figures to think about:

(The following averages are NOT any sort of scientific data. They're based on my own experiences and phone calls to other neurologists.)

- Speaking for a drug company: $750 per hour.

- Legal work: $400 per hour.

- Clinical trials research: $350 per hour.

- Market research: $250 per hour.

- Actually caring for patients: $100 per hour (real money, not the amounts we charge insurance companies, knowing we'll never collect them).

I know that many nondoctors will look at the above and say, "$100 per hour sounds great! These docs should shut up and take it!" Those people, however, are not in the position of also having to pay for rent, malpractice insurance, staff salaries, office supplies, and student loans, each at five to six figures per year.

Do the priorities on this list seem screwed up to anyone else out there? Obviously, clinical research for future medications is important, but does it seem odd that I can make more money for legal work or market research than, say, directly helping people?

You bet. But they do pay more, and so many of us are rapidly gravitating to them as supplemental income. The economics don't give us many other choices. If we want to help patients, we have to be able to keep our practices open.

I think this is sad because, when we all started out applying to medical school, most of us just wanted to care for people. But these days that's the least valued thing we do.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Finances are a big part of our lives. We may have become doctors to help people, but we're also supporting families.

The main job, for most of us, is to take care of patients. That's allegedly what we're most appreciated for, so shouldn't it be what pays the bills?

Patient care is still my bread and butter, but here are some dollar figures to think about:

(The following averages are NOT any sort of scientific data. They're based on my own experiences and phone calls to other neurologists.)

- Speaking for a drug company: $750 per hour.

- Legal work: $400 per hour.

- Clinical trials research: $350 per hour.

- Market research: $250 per hour.

- Actually caring for patients: $100 per hour (real money, not the amounts we charge insurance companies, knowing we'll never collect them).

I know that many nondoctors will look at the above and say, "$100 per hour sounds great! These docs should shut up and take it!" Those people, however, are not in the position of also having to pay for rent, malpractice insurance, staff salaries, office supplies, and student loans, each at five to six figures per year.

Do the priorities on this list seem screwed up to anyone else out there? Obviously, clinical research for future medications is important, but does it seem odd that I can make more money for legal work or market research than, say, directly helping people?

You bet. But they do pay more, and so many of us are rapidly gravitating to them as supplemental income. The economics don't give us many other choices. If we want to help patients, we have to be able to keep our practices open.

I think this is sad because, when we all started out applying to medical school, most of us just wanted to care for people. But these days that's the least valued thing we do.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.