User login

Jump starting thankfulness

One night, at the beginning of Thanksgiving week, my son called from his place across town. His car was having trouble starting, so I went to see what was up.

I got to his place to find his car wouldn’t start, even though the battery was only a few months old. I used my car to jump his, left him mine, and headed back. My plan was to leave it at our usual repair place and walk home.

Easier said than done.

I’d just gotten on the 101, the main loop freeway for the Phoenix metro area, when his car completely died. The lights flickered, the gauges stopped working, and then the engine cut out. Mercifully I was able to pull over into the right emergency lane as it did so. I was nowhere near an exit.

Not even the emergency flashers worked. It was dark. I was on a major freeway. I couldn’t make myself visible. Cars and trucks were whizzing by 2-3 feet to my left, and I was hoping they’d see me.

I called AAA and explained the situation. They were sending a tow truck, but it could take up to another 3 hours. I sent some quick texts to family to let them know what was up. I called the AZ highway patrol to let them know my predicament, in case they wanted to come put a flare or two behind me (they didn’t).

And then I settled in. Seatbelt on, staring at the road in front of me ... and had nothing to do.

When was the last time you had absolutely nothing to do?

It’s pretty rare these days. I mean, we all have breaks in the action, so we watch a cute animal video, or play a round of Wordle, or whatever.

But I had none of that. No books, iPad, or computer. Sure, I had my phone, but it was less than 50% charged with no way to charge it, and so I wanted to conserve that in case I needed it.

I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment like this since I began carrying a phone in 1998. There was, literally, nothing to do but wait. I couldn’t even try to nod off with the seat unadjustable and cars whizzing by.

So my mind wandered, and I thought. I turned over office cases. I went through year-end finances. I thought about my current predicament. I stared endlessly at the road ahead and cars passing me.

At some point I began to realize that I’m actually pretty lucky, and that nothing was nearly as bad as it had seemed earlier in the day. As the initial adrenaline rush drained out of me I calmed down and the things I’d been worrying about that afternoon seemed workable.

The tow truck pulled in front of me, ending my reverie. Mercifully, it had only taken them an hour. I was home 45 minutes later.

I was thankful to be home and I was thankful that nothing more serious had happened in a potentially bad situation.

And, somewhere in there,

In today’s world of endless screens and texts and calls and notifications, it’s easy to lose track of that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One night, at the beginning of Thanksgiving week, my son called from his place across town. His car was having trouble starting, so I went to see what was up.

I got to his place to find his car wouldn’t start, even though the battery was only a few months old. I used my car to jump his, left him mine, and headed back. My plan was to leave it at our usual repair place and walk home.

Easier said than done.

I’d just gotten on the 101, the main loop freeway for the Phoenix metro area, when his car completely died. The lights flickered, the gauges stopped working, and then the engine cut out. Mercifully I was able to pull over into the right emergency lane as it did so. I was nowhere near an exit.

Not even the emergency flashers worked. It was dark. I was on a major freeway. I couldn’t make myself visible. Cars and trucks were whizzing by 2-3 feet to my left, and I was hoping they’d see me.

I called AAA and explained the situation. They were sending a tow truck, but it could take up to another 3 hours. I sent some quick texts to family to let them know what was up. I called the AZ highway patrol to let them know my predicament, in case they wanted to come put a flare or two behind me (they didn’t).

And then I settled in. Seatbelt on, staring at the road in front of me ... and had nothing to do.

When was the last time you had absolutely nothing to do?

It’s pretty rare these days. I mean, we all have breaks in the action, so we watch a cute animal video, or play a round of Wordle, or whatever.

But I had none of that. No books, iPad, or computer. Sure, I had my phone, but it was less than 50% charged with no way to charge it, and so I wanted to conserve that in case I needed it.

I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment like this since I began carrying a phone in 1998. There was, literally, nothing to do but wait. I couldn’t even try to nod off with the seat unadjustable and cars whizzing by.

So my mind wandered, and I thought. I turned over office cases. I went through year-end finances. I thought about my current predicament. I stared endlessly at the road ahead and cars passing me.

At some point I began to realize that I’m actually pretty lucky, and that nothing was nearly as bad as it had seemed earlier in the day. As the initial adrenaline rush drained out of me I calmed down and the things I’d been worrying about that afternoon seemed workable.

The tow truck pulled in front of me, ending my reverie. Mercifully, it had only taken them an hour. I was home 45 minutes later.

I was thankful to be home and I was thankful that nothing more serious had happened in a potentially bad situation.

And, somewhere in there,

In today’s world of endless screens and texts and calls and notifications, it’s easy to lose track of that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

One night, at the beginning of Thanksgiving week, my son called from his place across town. His car was having trouble starting, so I went to see what was up.

I got to his place to find his car wouldn’t start, even though the battery was only a few months old. I used my car to jump his, left him mine, and headed back. My plan was to leave it at our usual repair place and walk home.

Easier said than done.

I’d just gotten on the 101, the main loop freeway for the Phoenix metro area, when his car completely died. The lights flickered, the gauges stopped working, and then the engine cut out. Mercifully I was able to pull over into the right emergency lane as it did so. I was nowhere near an exit.

Not even the emergency flashers worked. It was dark. I was on a major freeway. I couldn’t make myself visible. Cars and trucks were whizzing by 2-3 feet to my left, and I was hoping they’d see me.

I called AAA and explained the situation. They were sending a tow truck, but it could take up to another 3 hours. I sent some quick texts to family to let them know what was up. I called the AZ highway patrol to let them know my predicament, in case they wanted to come put a flare or two behind me (they didn’t).

And then I settled in. Seatbelt on, staring at the road in front of me ... and had nothing to do.

When was the last time you had absolutely nothing to do?

It’s pretty rare these days. I mean, we all have breaks in the action, so we watch a cute animal video, or play a round of Wordle, or whatever.

But I had none of that. No books, iPad, or computer. Sure, I had my phone, but it was less than 50% charged with no way to charge it, and so I wanted to conserve that in case I needed it.

I don’t think I’ve ever had a moment like this since I began carrying a phone in 1998. There was, literally, nothing to do but wait. I couldn’t even try to nod off with the seat unadjustable and cars whizzing by.

So my mind wandered, and I thought. I turned over office cases. I went through year-end finances. I thought about my current predicament. I stared endlessly at the road ahead and cars passing me.

At some point I began to realize that I’m actually pretty lucky, and that nothing was nearly as bad as it had seemed earlier in the day. As the initial adrenaline rush drained out of me I calmed down and the things I’d been worrying about that afternoon seemed workable.

The tow truck pulled in front of me, ending my reverie. Mercifully, it had only taken them an hour. I was home 45 minutes later.

I was thankful to be home and I was thankful that nothing more serious had happened in a potentially bad situation.

And, somewhere in there,

In today’s world of endless screens and texts and calls and notifications, it’s easy to lose track of that.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Earlier diagnosis of Alzheimer’s: A good start, but then what?

In the October 2022 issue of JAMA Neurology was a research article and accompanying editorial on the ATN (amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration) framework for diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease.

If the new generation of Alzheimer’s treatments can reverse pathology before the symptoms are apparent, it certainly makes sense to treat people as early as possible. In a terrible disease with only partially effective treatments now, this is encouraging news.

So this testing, as it stands now, would involve amyloid PET and tau PET scans, not to mention other screening tests such as MRI, labs, and the occasional lumbar puncture or EEG.

But it raises new questions.

Who should we be testing? If the new agents work on a presymptomatic basis, should we test everyone over 50, or 60, or 70? Or just those with memory concerns? Realistically, a lot of people come to general neurologists with memory worries, the majority of whom have nothing ominous. Those numbers are going to skyrocket as soon as the “have you been forgetting things? Ask your doctor” ads hit the airwaves. They’ll suggest, as much as the FDA will allow, that if you can’t find your car keys, you may have early dementia and need to be worked up promptly to keep from getting worse.

Who’s going to see these people? I’m sure it’s good for business, which I have no problem with, but most neurology practices are booked out a bit as it is. The influx of people panicked because they forgot their Netflix password will add to that.

How are we going to treat them? Even if we ignore aducanumab, which has more than enough baggage, lecanemab, donanemab, and gantenerumab are all waiting in the wings. Is one drug better for patients with certain scan findings? Or clearly safer? Keep in mind that, even at this early stage, we are already grappling with the potentially serious complication of ARIA [amyloid related imaging abnormalities]. The incidence is only going to go up as these new drugs enter the market. These questions rapidly move the drug outside the comfort zone of many general neurologists, and there aren’t nearly enough dementia subspecialists out there to handle the number of patients involved.

And lastly, from the more practical view, who’s going to pay for this? I’m not trying to prioritize money over people, but it’s a legitimate question that will have to be answered. PET scans aren’t cheap, and we’re talking about doing two of them. Neither are MRIs, or lumbar punctures. If we’re going to put guidelines out (like we do for mammograms and colonoscopies) for screening asymptomatic people over 70, or even mildly forgetful patients ... that’s a lot of dollars. Is there going to be some limitation on the testing based on who would benefit the most? What do we tell the patients and families outside of that range? And that’s even before we start factoring in the drug costs. In October, Forbes listed potential lecanemab prices as being anywhere from $9,000 to $35,000 per year.

I’m not trying to be Debbie Downer here. The fact that these drugs are here is, hopefully, the start of a new era in treatment of what will still be an incurable disease. Aricept (and its cousins) and Namenda were stepping stones in their day, and these are the next ones.

But these are questions that need to be answered. And soon.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the October 2022 issue of JAMA Neurology was a research article and accompanying editorial on the ATN (amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration) framework for diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease.

If the new generation of Alzheimer’s treatments can reverse pathology before the symptoms are apparent, it certainly makes sense to treat people as early as possible. In a terrible disease with only partially effective treatments now, this is encouraging news.

So this testing, as it stands now, would involve amyloid PET and tau PET scans, not to mention other screening tests such as MRI, labs, and the occasional lumbar puncture or EEG.

But it raises new questions.

Who should we be testing? If the new agents work on a presymptomatic basis, should we test everyone over 50, or 60, or 70? Or just those with memory concerns? Realistically, a lot of people come to general neurologists with memory worries, the majority of whom have nothing ominous. Those numbers are going to skyrocket as soon as the “have you been forgetting things? Ask your doctor” ads hit the airwaves. They’ll suggest, as much as the FDA will allow, that if you can’t find your car keys, you may have early dementia and need to be worked up promptly to keep from getting worse.

Who’s going to see these people? I’m sure it’s good for business, which I have no problem with, but most neurology practices are booked out a bit as it is. The influx of people panicked because they forgot their Netflix password will add to that.

How are we going to treat them? Even if we ignore aducanumab, which has more than enough baggage, lecanemab, donanemab, and gantenerumab are all waiting in the wings. Is one drug better for patients with certain scan findings? Or clearly safer? Keep in mind that, even at this early stage, we are already grappling with the potentially serious complication of ARIA [amyloid related imaging abnormalities]. The incidence is only going to go up as these new drugs enter the market. These questions rapidly move the drug outside the comfort zone of many general neurologists, and there aren’t nearly enough dementia subspecialists out there to handle the number of patients involved.

And lastly, from the more practical view, who’s going to pay for this? I’m not trying to prioritize money over people, but it’s a legitimate question that will have to be answered. PET scans aren’t cheap, and we’re talking about doing two of them. Neither are MRIs, or lumbar punctures. If we’re going to put guidelines out (like we do for mammograms and colonoscopies) for screening asymptomatic people over 70, or even mildly forgetful patients ... that’s a lot of dollars. Is there going to be some limitation on the testing based on who would benefit the most? What do we tell the patients and families outside of that range? And that’s even before we start factoring in the drug costs. In October, Forbes listed potential lecanemab prices as being anywhere from $9,000 to $35,000 per year.

I’m not trying to be Debbie Downer here. The fact that these drugs are here is, hopefully, the start of a new era in treatment of what will still be an incurable disease. Aricept (and its cousins) and Namenda were stepping stones in their day, and these are the next ones.

But these are questions that need to be answered. And soon.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In the October 2022 issue of JAMA Neurology was a research article and accompanying editorial on the ATN (amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration) framework for diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease.

If the new generation of Alzheimer’s treatments can reverse pathology before the symptoms are apparent, it certainly makes sense to treat people as early as possible. In a terrible disease with only partially effective treatments now, this is encouraging news.

So this testing, as it stands now, would involve amyloid PET and tau PET scans, not to mention other screening tests such as MRI, labs, and the occasional lumbar puncture or EEG.

But it raises new questions.

Who should we be testing? If the new agents work on a presymptomatic basis, should we test everyone over 50, or 60, or 70? Or just those with memory concerns? Realistically, a lot of people come to general neurologists with memory worries, the majority of whom have nothing ominous. Those numbers are going to skyrocket as soon as the “have you been forgetting things? Ask your doctor” ads hit the airwaves. They’ll suggest, as much as the FDA will allow, that if you can’t find your car keys, you may have early dementia and need to be worked up promptly to keep from getting worse.

Who’s going to see these people? I’m sure it’s good for business, which I have no problem with, but most neurology practices are booked out a bit as it is. The influx of people panicked because they forgot their Netflix password will add to that.

How are we going to treat them? Even if we ignore aducanumab, which has more than enough baggage, lecanemab, donanemab, and gantenerumab are all waiting in the wings. Is one drug better for patients with certain scan findings? Or clearly safer? Keep in mind that, even at this early stage, we are already grappling with the potentially serious complication of ARIA [amyloid related imaging abnormalities]. The incidence is only going to go up as these new drugs enter the market. These questions rapidly move the drug outside the comfort zone of many general neurologists, and there aren’t nearly enough dementia subspecialists out there to handle the number of patients involved.

And lastly, from the more practical view, who’s going to pay for this? I’m not trying to prioritize money over people, but it’s a legitimate question that will have to be answered. PET scans aren’t cheap, and we’re talking about doing two of them. Neither are MRIs, or lumbar punctures. If we’re going to put guidelines out (like we do for mammograms and colonoscopies) for screening asymptomatic people over 70, or even mildly forgetful patients ... that’s a lot of dollars. Is there going to be some limitation on the testing based on who would benefit the most? What do we tell the patients and families outside of that range? And that’s even before we start factoring in the drug costs. In October, Forbes listed potential lecanemab prices as being anywhere from $9,000 to $35,000 per year.

I’m not trying to be Debbie Downer here. The fact that these drugs are here is, hopefully, the start of a new era in treatment of what will still be an incurable disease. Aricept (and its cousins) and Namenda were stepping stones in their day, and these are the next ones.

But these are questions that need to be answered. And soon.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

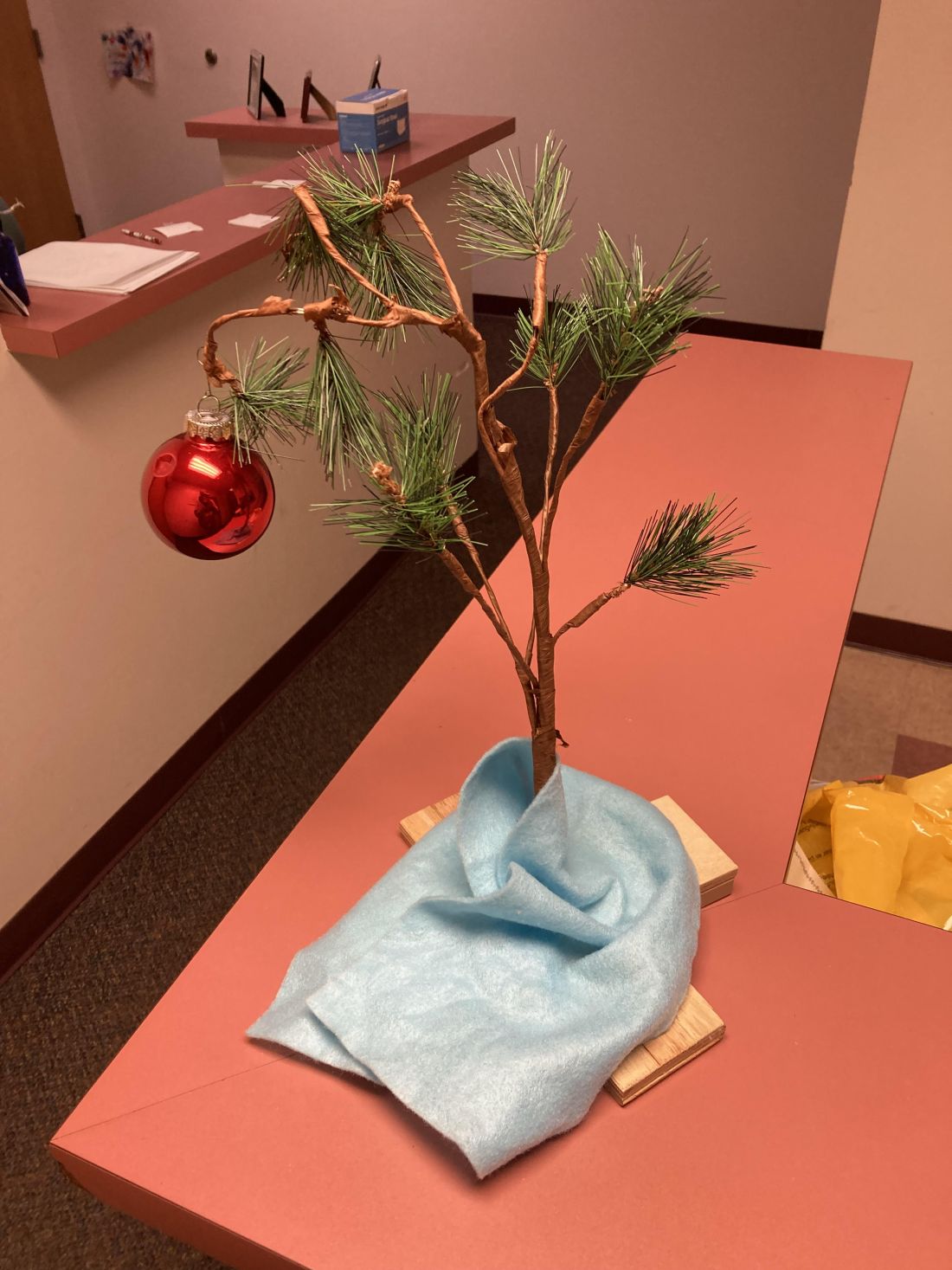

The Charlie Brown tree

I put a Christmas tree up early in November.

It’s not like it’s a real tree, or even a fancy one. For that matter, I’m Jewish.

Growing up in the 1970s one thing that could be relied on every year was the Charlie Brown Christmas special. It never changed. By age 5 you knew most of the lines, and loved the highlight when Charlie Brown brings home the saddest-looking tree ever, which collapses when he puts a single bauble on it.

Years ago, my kids gave me a Charlie Brown tree as a gift. It even plays the late Vince Guaraldi’s immortal Peanuts theme when you push a button. I forgot about it for a few years, then discovered it, and immediately brought it to my office.

I’m not a fan of holiday creep, where they move up earlier in the year, so I used to put it up after Thanksgiving. But we close the office 2-3 weeks later for the rest of the year. I like the tree, my staff likes the tree, and my patients like the tree, so I just started putting it up in early November so we can enjoy it for a month.

It’s whimsical and brings back memories of innocence, childhood, and (of course) Peanuts. It sets a cheerful tone when you see it there. Very few of my patients can resist pressing the button and playing the music as they go by.

The start of a new year is a relatively arbitrary date, chosen long ago. But its approach is always a reminder that life goes on. We continue our trips around the sun. Good times and bad times come and go, but time never stops.

In bad years the tree reminds me that it’s coming to an end, and to look toward the next. In good years it reminds me that it’s time to be ready for the surprises of the coming one.

In mid-December, after the patients are done for the last day of the year, I quietly put it away. It’s a vaguely somber moment, but at the same time I’m glad to know I now have 2-3 weeks of home time. It mostly involves working at my desk and returning phone calls, but there’s also time to relax with my kids, do jigsaw puzzles, and enjoy the Phoenix winter weather as a break before the next round starts.

To those who disagree with my choice of decoration or its timing, I simply respond: “Good grief!”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I put a Christmas tree up early in November.

It’s not like it’s a real tree, or even a fancy one. For that matter, I’m Jewish.

Growing up in the 1970s one thing that could be relied on every year was the Charlie Brown Christmas special. It never changed. By age 5 you knew most of the lines, and loved the highlight when Charlie Brown brings home the saddest-looking tree ever, which collapses when he puts a single bauble on it.

Years ago, my kids gave me a Charlie Brown tree as a gift. It even plays the late Vince Guaraldi’s immortal Peanuts theme when you push a button. I forgot about it for a few years, then discovered it, and immediately brought it to my office.

I’m not a fan of holiday creep, where they move up earlier in the year, so I used to put it up after Thanksgiving. But we close the office 2-3 weeks later for the rest of the year. I like the tree, my staff likes the tree, and my patients like the tree, so I just started putting it up in early November so we can enjoy it for a month.

It’s whimsical and brings back memories of innocence, childhood, and (of course) Peanuts. It sets a cheerful tone when you see it there. Very few of my patients can resist pressing the button and playing the music as they go by.

The start of a new year is a relatively arbitrary date, chosen long ago. But its approach is always a reminder that life goes on. We continue our trips around the sun. Good times and bad times come and go, but time never stops.

In bad years the tree reminds me that it’s coming to an end, and to look toward the next. In good years it reminds me that it’s time to be ready for the surprises of the coming one.

In mid-December, after the patients are done for the last day of the year, I quietly put it away. It’s a vaguely somber moment, but at the same time I’m glad to know I now have 2-3 weeks of home time. It mostly involves working at my desk and returning phone calls, but there’s also time to relax with my kids, do jigsaw puzzles, and enjoy the Phoenix winter weather as a break before the next round starts.

To those who disagree with my choice of decoration or its timing, I simply respond: “Good grief!”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I put a Christmas tree up early in November.

It’s not like it’s a real tree, or even a fancy one. For that matter, I’m Jewish.

Growing up in the 1970s one thing that could be relied on every year was the Charlie Brown Christmas special. It never changed. By age 5 you knew most of the lines, and loved the highlight when Charlie Brown brings home the saddest-looking tree ever, which collapses when he puts a single bauble on it.

Years ago, my kids gave me a Charlie Brown tree as a gift. It even plays the late Vince Guaraldi’s immortal Peanuts theme when you push a button. I forgot about it for a few years, then discovered it, and immediately brought it to my office.

I’m not a fan of holiday creep, where they move up earlier in the year, so I used to put it up after Thanksgiving. But we close the office 2-3 weeks later for the rest of the year. I like the tree, my staff likes the tree, and my patients like the tree, so I just started putting it up in early November so we can enjoy it for a month.

It’s whimsical and brings back memories of innocence, childhood, and (of course) Peanuts. It sets a cheerful tone when you see it there. Very few of my patients can resist pressing the button and playing the music as they go by.

The start of a new year is a relatively arbitrary date, chosen long ago. But its approach is always a reminder that life goes on. We continue our trips around the sun. Good times and bad times come and go, but time never stops.

In bad years the tree reminds me that it’s coming to an end, and to look toward the next. In good years it reminds me that it’s time to be ready for the surprises of the coming one.

In mid-December, after the patients are done for the last day of the year, I quietly put it away. It’s a vaguely somber moment, but at the same time I’m glad to know I now have 2-3 weeks of home time. It mostly involves working at my desk and returning phone calls, but there’s also time to relax with my kids, do jigsaw puzzles, and enjoy the Phoenix winter weather as a break before the next round starts.

To those who disagree with my choice of decoration or its timing, I simply respond: “Good grief!”

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Software templates: Use at your own peril

Recently a fax showed up containing a patient referral, which is a pretty normal event around here. It was from a doctor I’ve never heard of, but that’s not surprising. The medical field is always in turnover.

Like most fax referrals, this one had a cover sheet and briefly explained who the patient is, who referred them, and why. But under that it said: “By receiving this fax you agree to the following conditions:

- 1. You will contact the patient within 24 hours of receipt.

- 2. The patient will be seen within 1 week of contacting them.

- 3. You will provide a report to the referring physician within 24 hours of seeing the patient.”

Okay ...

Who are these people?

Does anyone else think the tone is kind of grating, if not rude? It sounds like they’re telling me how to run my office.

“By receiving this fax ...” what does that mean? I receive faxes all day, most of them telling me about great vacation deals, low prices on Botox, and medical supplies I don’t need. Just because I receive them doesn’t mean anything.

And, as I’ve previously written here, my office policy is that we don’t call patients just based on a fax. That opens up a whole new can of worms. It’s up to patients to call us.

But realistically, the other doctor may have no idea it’s on their cover sheet. It could be the work of a receptionist, or office manager, or just the default page for a software suite they use. In fact, the last one is the most likely cause.

One of the problems (there are too many to count, but I’m just going to address this one) in medical office software is the option to use templates. Use them at your own peril. If you’re not paying attention, you might sound incompetent at worst and rude at best.

Even something as innocuous as a fax cover sheet, written by a nonmedical person, can sound bad.

Regardless of how harmless and unintentional it might be, it can leave a bad taste in the mouths of patients and other offices. If something that minor isn’t good, I’m hoping someone is checking the templates for patient visits.

I’m sure no offense was meant, and none was taken. But it reinforces that Unless you (or a trusted person who knows your habits) checks it, you run the risk of it coming back to bite you.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently a fax showed up containing a patient referral, which is a pretty normal event around here. It was from a doctor I’ve never heard of, but that’s not surprising. The medical field is always in turnover.

Like most fax referrals, this one had a cover sheet and briefly explained who the patient is, who referred them, and why. But under that it said: “By receiving this fax you agree to the following conditions:

- 1. You will contact the patient within 24 hours of receipt.

- 2. The patient will be seen within 1 week of contacting them.

- 3. You will provide a report to the referring physician within 24 hours of seeing the patient.”

Okay ...

Who are these people?

Does anyone else think the tone is kind of grating, if not rude? It sounds like they’re telling me how to run my office.

“By receiving this fax ...” what does that mean? I receive faxes all day, most of them telling me about great vacation deals, low prices on Botox, and medical supplies I don’t need. Just because I receive them doesn’t mean anything.

And, as I’ve previously written here, my office policy is that we don’t call patients just based on a fax. That opens up a whole new can of worms. It’s up to patients to call us.

But realistically, the other doctor may have no idea it’s on their cover sheet. It could be the work of a receptionist, or office manager, or just the default page for a software suite they use. In fact, the last one is the most likely cause.

One of the problems (there are too many to count, but I’m just going to address this one) in medical office software is the option to use templates. Use them at your own peril. If you’re not paying attention, you might sound incompetent at worst and rude at best.

Even something as innocuous as a fax cover sheet, written by a nonmedical person, can sound bad.

Regardless of how harmless and unintentional it might be, it can leave a bad taste in the mouths of patients and other offices. If something that minor isn’t good, I’m hoping someone is checking the templates for patient visits.

I’m sure no offense was meant, and none was taken. But it reinforces that Unless you (or a trusted person who knows your habits) checks it, you run the risk of it coming back to bite you.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently a fax showed up containing a patient referral, which is a pretty normal event around here. It was from a doctor I’ve never heard of, but that’s not surprising. The medical field is always in turnover.

Like most fax referrals, this one had a cover sheet and briefly explained who the patient is, who referred them, and why. But under that it said: “By receiving this fax you agree to the following conditions:

- 1. You will contact the patient within 24 hours of receipt.

- 2. The patient will be seen within 1 week of contacting them.

- 3. You will provide a report to the referring physician within 24 hours of seeing the patient.”

Okay ...

Who are these people?

Does anyone else think the tone is kind of grating, if not rude? It sounds like they’re telling me how to run my office.

“By receiving this fax ...” what does that mean? I receive faxes all day, most of them telling me about great vacation deals, low prices on Botox, and medical supplies I don’t need. Just because I receive them doesn’t mean anything.

And, as I’ve previously written here, my office policy is that we don’t call patients just based on a fax. That opens up a whole new can of worms. It’s up to patients to call us.

But realistically, the other doctor may have no idea it’s on their cover sheet. It could be the work of a receptionist, or office manager, or just the default page for a software suite they use. In fact, the last one is the most likely cause.

One of the problems (there are too many to count, but I’m just going to address this one) in medical office software is the option to use templates. Use them at your own peril. If you’re not paying attention, you might sound incompetent at worst and rude at best.

Even something as innocuous as a fax cover sheet, written by a nonmedical person, can sound bad.

Regardless of how harmless and unintentional it might be, it can leave a bad taste in the mouths of patients and other offices. If something that minor isn’t good, I’m hoping someone is checking the templates for patient visits.

I’m sure no offense was meant, and none was taken. But it reinforces that Unless you (or a trusted person who knows your habits) checks it, you run the risk of it coming back to bite you.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Should health care be a right?

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Is health care a human right?

This year voters in Oregon are being asked to decide that.

It brings up some interesting questions. Should it be a right? Food, water, shelter, and oxygen aren’t, as far as I know, considered such. So why health care?

Probably the main argument against the idea is that, if it’s a right, shouldn’t the government (and therefore taxpayers) be tasked with paying for it all?

Good question, and not one that I can answer. If my neighbor refuses to buy insurance, then has a health crisis he can’t afford, why should I have to pay for his obstinacy and lack of foresight? Isn’t it his problem?

Of course, the truth is that not everyone can afford health care, or insurance. They ain’t cheap. Even if you get coverage through your job, part of your earnings, and part of the company’s profits, are being taken out to pay for it.

This raises the question of whether health care is something that should be rationed only to the working, successfully retired, or wealthy. Heaven knows I have plenty of patients tell me that. Their point is that if you’re not contributing to society, why should society contribute to you?

One even said that our distant ancestors didn’t see an issue with this: If you were unable to hunt, or outrun a cave lion, you probably weren’t helping the rest of the tribe anyway and deserved what happened to you.

Perhaps true, but we aren’t our distant ancestors. Over the millennia we’ve developed into a remarkably social, and increasingly interconnected, species. Somewhat paradoxically we often care more about famines on the other side of the world than we do in our own cities. If you’re going to use the argument of “we didn’t used to do this,” we also didn’t used to have cars, planes, or computers, but I don’t see anyone giving them up.

Another thing to keep in mind is that we are all paying for the uninsured under pretty much any system of health care there is. Whether it’s through taxes, insurance premiums, or both, our own costs go up to pay the bills of those who don’t have coverage. So in that respect the financial aspect of declaring it a right probably doesn’t change the de facto truth of the situation. It just makes it more official-ish.

Maybe the statement has more philosophical or political meaning than it does practical. If it passes it may change a lot of things, or nothing at all, depending how it’s legally interpreted.

Like so many things, we won’t know where it goes unless it happens. And even then it’s uncertain where it will lead.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Asking about gun ownership: A loaded question?

Recently there have been articles and discussions about how involved physicians should be in patient gun ownership.

There are valid points all around. Some of my colleagues, especially those in general practice, feel that they don’t have enough time to add more screening questions on top of those they already have. Others point out that routinely asking about gun ownership is none of our business. A third view I’ve seen is that very few doctors are in a position to teach issues of gun safety.

In my field, with certain patients, I do ask. Namely, the demented.

Anyone with concerning cognitive deficits shouldn’t have access to guns. As their judgment fades and their impulsivity worsens, they often don’t realize right from wrong. They might open fire on family members thinking they’re burglars. Some of them see suspicious people out in the yard that are more likely hallucinations or simply passersby.

In more advanced cases of dementia, patients may not even realize what they’re holding, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous. Probably more so, since they’re not going to be careful with it.

Another scary issue I sometimes encounter is when patients with dementia find a gun at home – usually one that belonged to a deceased spouse and that family isn’t aware of. No one really knows if it’s working, or loaded, though we have to assume it is. They find it and start carrying it out on walks, pointing it at the mailman who they think is trespassing, etc. Sometimes the police get called. These situations are extremely dangerous for all involved.

It’s pretty easy for someone to get shot under these circumstances. It’s like leaving a gun out and having a toddler find it. They don’t mean any harm, but they’re still just as deadly as someone who does.

These people also have access to knives, which can be equally deadly, but knives aren’t guns. They don’t have the range or hitting power that make firearms so dangerous. It’s a lot easier to disarm an elderly patient with a steak knife if need be.

So, like my colleagues in psychiatry, I ask about guns in certain situations that involve dementia. Are there any guns? If so, are they locked up safely where the person can’t access them?

I’m not making a statement for or against gun ownership here. But I think all of us would agree that

In neurology, that’s a decent chunk of my patients. So for everyone’s safety, I ask them (and, more importantly, their families) about guns.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently there have been articles and discussions about how involved physicians should be in patient gun ownership.

There are valid points all around. Some of my colleagues, especially those in general practice, feel that they don’t have enough time to add more screening questions on top of those they already have. Others point out that routinely asking about gun ownership is none of our business. A third view I’ve seen is that very few doctors are in a position to teach issues of gun safety.

In my field, with certain patients, I do ask. Namely, the demented.

Anyone with concerning cognitive deficits shouldn’t have access to guns. As their judgment fades and their impulsivity worsens, they often don’t realize right from wrong. They might open fire on family members thinking they’re burglars. Some of them see suspicious people out in the yard that are more likely hallucinations or simply passersby.

In more advanced cases of dementia, patients may not even realize what they’re holding, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous. Probably more so, since they’re not going to be careful with it.

Another scary issue I sometimes encounter is when patients with dementia find a gun at home – usually one that belonged to a deceased spouse and that family isn’t aware of. No one really knows if it’s working, or loaded, though we have to assume it is. They find it and start carrying it out on walks, pointing it at the mailman who they think is trespassing, etc. Sometimes the police get called. These situations are extremely dangerous for all involved.

It’s pretty easy for someone to get shot under these circumstances. It’s like leaving a gun out and having a toddler find it. They don’t mean any harm, but they’re still just as deadly as someone who does.

These people also have access to knives, which can be equally deadly, but knives aren’t guns. They don’t have the range or hitting power that make firearms so dangerous. It’s a lot easier to disarm an elderly patient with a steak knife if need be.

So, like my colleagues in psychiatry, I ask about guns in certain situations that involve dementia. Are there any guns? If so, are they locked up safely where the person can’t access them?

I’m not making a statement for or against gun ownership here. But I think all of us would agree that

In neurology, that’s a decent chunk of my patients. So for everyone’s safety, I ask them (and, more importantly, their families) about guns.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently there have been articles and discussions about how involved physicians should be in patient gun ownership.

There are valid points all around. Some of my colleagues, especially those in general practice, feel that they don’t have enough time to add more screening questions on top of those they already have. Others point out that routinely asking about gun ownership is none of our business. A third view I’ve seen is that very few doctors are in a position to teach issues of gun safety.

In my field, with certain patients, I do ask. Namely, the demented.

Anyone with concerning cognitive deficits shouldn’t have access to guns. As their judgment fades and their impulsivity worsens, they often don’t realize right from wrong. They might open fire on family members thinking they’re burglars. Some of them see suspicious people out in the yard that are more likely hallucinations or simply passersby.

In more advanced cases of dementia, patients may not even realize what they’re holding, but that doesn’t make it any less dangerous. Probably more so, since they’re not going to be careful with it.

Another scary issue I sometimes encounter is when patients with dementia find a gun at home – usually one that belonged to a deceased spouse and that family isn’t aware of. No one really knows if it’s working, or loaded, though we have to assume it is. They find it and start carrying it out on walks, pointing it at the mailman who they think is trespassing, etc. Sometimes the police get called. These situations are extremely dangerous for all involved.

It’s pretty easy for someone to get shot under these circumstances. It’s like leaving a gun out and having a toddler find it. They don’t mean any harm, but they’re still just as deadly as someone who does.

These people also have access to knives, which can be equally deadly, but knives aren’t guns. They don’t have the range or hitting power that make firearms so dangerous. It’s a lot easier to disarm an elderly patient with a steak knife if need be.

So, like my colleagues in psychiatry, I ask about guns in certain situations that involve dementia. Are there any guns? If so, are they locked up safely where the person can’t access them?

I’m not making a statement for or against gun ownership here. But I think all of us would agree that

In neurology, that’s a decent chunk of my patients. So for everyone’s safety, I ask them (and, more importantly, their families) about guns.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Drug abusers will find a way

Recently, when I logged on to see what medication refills had come in, I was greeted with a notice that Walgreens would no longer carry promethazine/codeine cough syrup. It wouldn’t surprise me if other pharmacies follow.

This doesn’t affect me much. As a neurologist I’ve never prescribed it, and as a patient I’ve never used it.

The unwritten reason was likely because of its popularity for abuse. It is often mixed with various beverages and called “purple drank.” It has both social, and legal, consequences that can come back and bite the pharmacy.

A friend of mine commented that if everything that can be abused gets banned, all we’ll be left with are Tylenol and Preparation H. Another friend made the comment that it’s a shame, because codeine is a remarkably effective antitussive.

I agree with both of them, but Walgreens is pulling only the combo preparation off the shelves. Codeine and promethazine are still available. The former is on WHO’s list of essential medications.

They’d still find a way to get the components and whip up some equivalent. Human innovation can be remarkable. All of us who trained in the inner city (which is pretty much all of us at some point) have seen people who drank mouthwash, hairspray, and who knows what else in desperation.

No one believes it’s going to stop drug abuse, but it will make it harder to have purple drank, which is often passed around as a low-level drug at parties. Putting Sudafed behind the counter has reduced, though not stopped, meth. Walter White can tell you that.

A patient of mine who’s a pharmacist also was talking about this. He’s in favor of it, as he’s tired of dealing with people trying to get it through faked prescriptions and bogus visits to urgent care pretending to have a cough, not to mention the additional paperwork and reporting requirements that a controlled drug carries.

I agree with it, mostly, but there are those who truly do need it at times, and who now will have to take it as individual components, or find a pharmacy that does carry it. The issue here becomes that, by punishing the abusers, you’re also punishing the responsible.

The vast majority of alcohol users are responsible drinkers. I have the occasional beer myself. Unfortunately, there are a comparative few who aren’t, and their actions can bring tremendous grief to many others. So we have tougher laws all around that we all have to follow.

I agree with Walgreens actions on this, but still find myself wondering how much of a difference it will make.

Probably not as much as I hope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, when I logged on to see what medication refills had come in, I was greeted with a notice that Walgreens would no longer carry promethazine/codeine cough syrup. It wouldn’t surprise me if other pharmacies follow.

This doesn’t affect me much. As a neurologist I’ve never prescribed it, and as a patient I’ve never used it.

The unwritten reason was likely because of its popularity for abuse. It is often mixed with various beverages and called “purple drank.” It has both social, and legal, consequences that can come back and bite the pharmacy.

A friend of mine commented that if everything that can be abused gets banned, all we’ll be left with are Tylenol and Preparation H. Another friend made the comment that it’s a shame, because codeine is a remarkably effective antitussive.

I agree with both of them, but Walgreens is pulling only the combo preparation off the shelves. Codeine and promethazine are still available. The former is on WHO’s list of essential medications.

They’d still find a way to get the components and whip up some equivalent. Human innovation can be remarkable. All of us who trained in the inner city (which is pretty much all of us at some point) have seen people who drank mouthwash, hairspray, and who knows what else in desperation.

No one believes it’s going to stop drug abuse, but it will make it harder to have purple drank, which is often passed around as a low-level drug at parties. Putting Sudafed behind the counter has reduced, though not stopped, meth. Walter White can tell you that.

A patient of mine who’s a pharmacist also was talking about this. He’s in favor of it, as he’s tired of dealing with people trying to get it through faked prescriptions and bogus visits to urgent care pretending to have a cough, not to mention the additional paperwork and reporting requirements that a controlled drug carries.

I agree with it, mostly, but there are those who truly do need it at times, and who now will have to take it as individual components, or find a pharmacy that does carry it. The issue here becomes that, by punishing the abusers, you’re also punishing the responsible.

The vast majority of alcohol users are responsible drinkers. I have the occasional beer myself. Unfortunately, there are a comparative few who aren’t, and their actions can bring tremendous grief to many others. So we have tougher laws all around that we all have to follow.

I agree with Walgreens actions on this, but still find myself wondering how much of a difference it will make.

Probably not as much as I hope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently, when I logged on to see what medication refills had come in, I was greeted with a notice that Walgreens would no longer carry promethazine/codeine cough syrup. It wouldn’t surprise me if other pharmacies follow.

This doesn’t affect me much. As a neurologist I’ve never prescribed it, and as a patient I’ve never used it.

The unwritten reason was likely because of its popularity for abuse. It is often mixed with various beverages and called “purple drank.” It has both social, and legal, consequences that can come back and bite the pharmacy.

A friend of mine commented that if everything that can be abused gets banned, all we’ll be left with are Tylenol and Preparation H. Another friend made the comment that it’s a shame, because codeine is a remarkably effective antitussive.

I agree with both of them, but Walgreens is pulling only the combo preparation off the shelves. Codeine and promethazine are still available. The former is on WHO’s list of essential medications.

They’d still find a way to get the components and whip up some equivalent. Human innovation can be remarkable. All of us who trained in the inner city (which is pretty much all of us at some point) have seen people who drank mouthwash, hairspray, and who knows what else in desperation.

No one believes it’s going to stop drug abuse, but it will make it harder to have purple drank, which is often passed around as a low-level drug at parties. Putting Sudafed behind the counter has reduced, though not stopped, meth. Walter White can tell you that.

A patient of mine who’s a pharmacist also was talking about this. He’s in favor of it, as he’s tired of dealing with people trying to get it through faked prescriptions and bogus visits to urgent care pretending to have a cough, not to mention the additional paperwork and reporting requirements that a controlled drug carries.

I agree with it, mostly, but there are those who truly do need it at times, and who now will have to take it as individual components, or find a pharmacy that does carry it. The issue here becomes that, by punishing the abusers, you’re also punishing the responsible.

The vast majority of alcohol users are responsible drinkers. I have the occasional beer myself. Unfortunately, there are a comparative few who aren’t, and their actions can bring tremendous grief to many others. So we have tougher laws all around that we all have to follow.

I agree with Walgreens actions on this, but still find myself wondering how much of a difference it will make.

Probably not as much as I hope.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Ruminations on health care spending

What could you do with $18 billion?

I could pay off my mortgage roughly 60,000 times, or take my wife on a never-ending world cruise so we don’t need a mortgage, or at least hire someone to clean my pool regularly so I don’t have to.

A recent report from the OIG found that, in the last 3 years, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spent $18 billion on drugs for which there’s no proof of significant clinical benefit.

That’s a lot of money on things that may or may not be placebos, some of which are WAY overdue on Food and Drug Administration–mandated efficacy studies. A few have even been on the market so long that they’ve become equally unproven generics.

Now, if you put this in the big picture, that immense amount of money is still only 2% of their total spending in health care. Hell, probably at least 2% of my personal spending is on pointless things, too. So, realistically, you could say 98% of CMS spending is on worthwhile care, which is as it should be.

But the bottom line is that I’m sure it could be better used in many other programs (refunding it to taxpayers comes out to maybe $55 for each of us, which probably isn’t worth the effort).

As pointed out in the movie “Dave,” shoving that kind of money in even a low-yield savings account would generate at least $180 million in interest each year.

That’s a lot of money, too, that could be used for something. Of course, no one in the government thinks that way. That’s why we all loved the movie.

The problem is that the phrase “no proof of significant clinical benefit” doesn’t mean something doesn’t work. It just means we aren’t sure. Some of those people on one of these drugs may be getting benefit – or not. After all, the placebo effect is remarkably strong. But if they are helping someone, who wants to be the one to tell them “we’re not going to pay for this anymore?”

Another issue is this: Let’s say the drugs only work for 10% of the people who take them ($1.8 billion worth), and for the other 90% it’s iffy ($16.2 billion worth), but the latter want to stay on them anyway, just to be sure. Do we cut them? Or just say that $18 billion is too much money when only 10% are being helped, and cut them all off? I’m sure we could use the money elsewhere (see “Dave” above), so let them find a way to work it out with the manufacturer. The greatest good for the greatest number and all that jazz.

I don’t know, either. Health care dollars are finite, and human suffering is infinite. It’s a balancing act that can’t be won. There are no easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

What could you do with $18 billion?

I could pay off my mortgage roughly 60,000 times, or take my wife on a never-ending world cruise so we don’t need a mortgage, or at least hire someone to clean my pool regularly so I don’t have to.

A recent report from the OIG found that, in the last 3 years, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spent $18 billion on drugs for which there’s no proof of significant clinical benefit.

That’s a lot of money on things that may or may not be placebos, some of which are WAY overdue on Food and Drug Administration–mandated efficacy studies. A few have even been on the market so long that they’ve become equally unproven generics.

Now, if you put this in the big picture, that immense amount of money is still only 2% of their total spending in health care. Hell, probably at least 2% of my personal spending is on pointless things, too. So, realistically, you could say 98% of CMS spending is on worthwhile care, which is as it should be.

But the bottom line is that I’m sure it could be better used in many other programs (refunding it to taxpayers comes out to maybe $55 for each of us, which probably isn’t worth the effort).

As pointed out in the movie “Dave,” shoving that kind of money in even a low-yield savings account would generate at least $180 million in interest each year.

That’s a lot of money, too, that could be used for something. Of course, no one in the government thinks that way. That’s why we all loved the movie.

The problem is that the phrase “no proof of significant clinical benefit” doesn’t mean something doesn’t work. It just means we aren’t sure. Some of those people on one of these drugs may be getting benefit – or not. After all, the placebo effect is remarkably strong. But if they are helping someone, who wants to be the one to tell them “we’re not going to pay for this anymore?”

Another issue is this: Let’s say the drugs only work for 10% of the people who take them ($1.8 billion worth), and for the other 90% it’s iffy ($16.2 billion worth), but the latter want to stay on them anyway, just to be sure. Do we cut them? Or just say that $18 billion is too much money when only 10% are being helped, and cut them all off? I’m sure we could use the money elsewhere (see “Dave” above), so let them find a way to work it out with the manufacturer. The greatest good for the greatest number and all that jazz.

I don’t know, either. Health care dollars are finite, and human suffering is infinite. It’s a balancing act that can’t be won. There are no easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

What could you do with $18 billion?

I could pay off my mortgage roughly 60,000 times, or take my wife on a never-ending world cruise so we don’t need a mortgage, or at least hire someone to clean my pool regularly so I don’t have to.

A recent report from the OIG found that, in the last 3 years, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services spent $18 billion on drugs for which there’s no proof of significant clinical benefit.

That’s a lot of money on things that may or may not be placebos, some of which are WAY overdue on Food and Drug Administration–mandated efficacy studies. A few have even been on the market so long that they’ve become equally unproven generics.

Now, if you put this in the big picture, that immense amount of money is still only 2% of their total spending in health care. Hell, probably at least 2% of my personal spending is on pointless things, too. So, realistically, you could say 98% of CMS spending is on worthwhile care, which is as it should be.

But the bottom line is that I’m sure it could be better used in many other programs (refunding it to taxpayers comes out to maybe $55 for each of us, which probably isn’t worth the effort).

As pointed out in the movie “Dave,” shoving that kind of money in even a low-yield savings account would generate at least $180 million in interest each year.

That’s a lot of money, too, that could be used for something. Of course, no one in the government thinks that way. That’s why we all loved the movie.

The problem is that the phrase “no proof of significant clinical benefit” doesn’t mean something doesn’t work. It just means we aren’t sure. Some of those people on one of these drugs may be getting benefit – or not. After all, the placebo effect is remarkably strong. But if they are helping someone, who wants to be the one to tell them “we’re not going to pay for this anymore?”

Another issue is this: Let’s say the drugs only work for 10% of the people who take them ($1.8 billion worth), and for the other 90% it’s iffy ($16.2 billion worth), but the latter want to stay on them anyway, just to be sure. Do we cut them? Or just say that $18 billion is too much money when only 10% are being helped, and cut them all off? I’m sure we could use the money elsewhere (see “Dave” above), so let them find a way to work it out with the manufacturer. The greatest good for the greatest number and all that jazz.

I don’t know, either. Health care dollars are finite, and human suffering is infinite. It’s a balancing act that can’t be won. There are no easy answers.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The dubious value of online reviews

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I hear other doctors talk about online reviews, both good and bad.

I recently read a piece where a practice gave doctors a bonus for getting 5-star reviews, though it doesn’t say if they were penalized for getting bad reviews. I assume the latter docs got a good “talking to” by someone in administration, or marketing, or both.

I get my share of them, too, both good and bad, scattered across at least a dozen sites that profess to offer accurate ratings.

I tend to ignore all of them.

Bad ratings mean nothing. They might be reasonable. They can also be from patients whom I fired for noncompliance, or from patients I refused to give an early narcotic refill to. They can also be from people who aren’t patients, such as a neighbor angry at the way I voted at a home owners association meeting, or a person who never saw me but was upset because I don’t take their insurance, or someone at the hospital whom I had to hang up on after being put on hold for 10 minutes.

Good reviews also don’t mean much, either. They might be from patients. They could also be from well-meaning family and friends. Or the waiter I left an extra-large tip for the other night.

One of my 1-star reviews even goes on to describe me in glowing terms (the lady called my office to apologize, saying the site confused her).

There’s also a whole cottage industry around this: Like restaurants, you can pay people to give you good reviews. They’re on Craig’s list and other sites. Some are freelancers. Others are actually well-organized companies, offering to give you X number of good reviews per month for a regular fee. I see ads for the latter online, usually describing themselves as “reputation recovery services.”

There was even a recent post on Sermo about this. A doctor noted he’d gotten a string of bad reviews from nonpatients, and shortly afterward was contacted by a reputation recovery service to help. He wondered if the crappy reviews were intentionally written by that business before they called him. He also questioned if it was an unspoken blackmail tactic – pay us or we’ll write more bad reviews.

Unlike a restaurant, we can’t respond because of patient confidentiality. Unless it’s something meaninglessly generic like “thank you” or “sorry you had a bad experience.”

A friend of mine (not in medicine) said that picking your doctor from online reviews is like selecting a wine recommended by a guy who lives at the train yard.

While there are pros and cons to the whole online review thing, in medicine there are mostly cons. Many reviews are anonymous, with no way to trace them. Unless details are provided, you don’t know if the reviewer is really a patient (or even a human in this bot era). Neither does the general public, reading them and presumably making decisions about who to see.

There are minimal (if any) rules, no law enforcement, and no one knows who the good guys and bad guys really are.

And there’s nothing we can do about it, either.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No such thing as an easy fix

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.

I’ve seen plenty of articles suggesting coffee and/or tea have health benefits, though specifically on what varies, from lifespan to lowering the risk of a chronic medical condition (in this case, type 2 diabetes).

There are always numerous variables that aren’t clear. What kind of tea? Decaf or regular? Hot or iced? When you say cup, what do you mean? A lot of people, including me, probably consider anything smaller that a Starbucks grande to be for wimps.

While I can’t think of any off the top of my head, there’s probably a reasonable chance that, if I looked, I could find something that says coffee or tea are bad for you in some way, too.

Not that I’m planning on changing my already caffeinated drinking habits, which is probably the crux of these things for most of us. In a given day I have 1-2 cups of coffee and 3-4 bottles of diet green tea. Maybe 1-2 Diet Cokes in there some days. In winter more hot black tea. I’m probably a poster child for methylyxanthine toxicity.

I have no idea if all that coffee and tea are doing anything besides keeping me awake and alert for my patients. If they are, I certainly hope they’re lowering my risk of something bad.

Articles like this always get attention, and are often picked up by the general media. People love to think something so simple as drinking more tea or coffee would make a big difference in their lives. So it gets forwarded, people never read past the first paragraph or two, and don’t make it to the “further research is needed” line.

If an article ever came out refuting it, it probably wouldn’t get nearly as much press (who wants to read bad news?) and would be quickly forgotten outside of medical circles.

But the reality is that people are really looking for shortcuts. Unless you live under a rock, it’s pretty clear to both medical and lay people that such things as exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid multiple chronic health conditions. This doesn’t mean most of us, myself included, will do such faithfully. It just takes less time and effort to drink more tea than it does to go to the gym, so we want to believe.

That’s just human nature.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.

I’ve seen plenty of articles suggesting coffee and/or tea have health benefits, though specifically on what varies, from lifespan to lowering the risk of a chronic medical condition (in this case, type 2 diabetes).

There are always numerous variables that aren’t clear. What kind of tea? Decaf or regular? Hot or iced? When you say cup, what do you mean? A lot of people, including me, probably consider anything smaller that a Starbucks grande to be for wimps.

While I can’t think of any off the top of my head, there’s probably a reasonable chance that, if I looked, I could find something that says coffee or tea are bad for you in some way, too.

Not that I’m planning on changing my already caffeinated drinking habits, which is probably the crux of these things for most of us. In a given day I have 1-2 cups of coffee and 3-4 bottles of diet green tea. Maybe 1-2 Diet Cokes in there some days. In winter more hot black tea. I’m probably a poster child for methylyxanthine toxicity.

I have no idea if all that coffee and tea are doing anything besides keeping me awake and alert for my patients. If they are, I certainly hope they’re lowering my risk of something bad.

Articles like this always get attention, and are often picked up by the general media. People love to think something so simple as drinking more tea or coffee would make a big difference in their lives. So it gets forwarded, people never read past the first paragraph or two, and don’t make it to the “further research is needed” line.

If an article ever came out refuting it, it probably wouldn’t get nearly as much press (who wants to read bad news?) and would be quickly forgotten outside of medical circles.

But the reality is that people are really looking for shortcuts. Unless you live under a rock, it’s pretty clear to both medical and lay people that such things as exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid multiple chronic health conditions. This doesn’t mean most of us, myself included, will do such faithfully. It just takes less time and effort to drink more tea than it does to go to the gym, so we want to believe.

That’s just human nature.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Recently an article crossed my screen that drinking 4 cups of tea per day lowered the risk of type 2 diabetes by 17%. As these thing always seem to, it ended with a variant of “further research is needed.”

Encouraging? Sure. Definite? Nope.