User login

An interview with incoming CHEST President, John Studdard, MD, FCCP

John Studdard, MD, FCCP, has been a member of the American College of Chest Physicians for 36 years, and, this November, he will be inaugurated as CHEST President. This will not be Dr. Studdard’s first time in a presidential role for CHEST, as he served as CHEST Foundation President in 2013 and 2014. Currently, Dr. Studdard serves as a pulmonologist at Jackson Pulmonary in Jackson, Mississippi. Being a physician and being as heavily involved with an organization as Dr. Studdard is takes a lot of prioritizing, hard work, and dedication. Get to know CHEST’s new President through this interview.

Born and raised in Mississippi, Dr. Studdard says there were four factors that inspired him to become a physician:

1. I have always loved people and working with them, and I always admired the respect that physicians received in my community.

3. I am competitive and decided if it was going to be hard to get into medical school, then I wanted to go to medical school.

4. My dad always told my brother and me that we would be doctors when we grew up, because we were going to be our own boss. I have been in private practice for 36 years, and that is not the case, not if you are doing it right. I obviously love medicine, and my dad was great in that he paid for our education…but he called the shots.

What are some of the biggest challenges you have encountered throughout your career?

Private practice makes you gain more independence and autonomy; you have to become more agile, more efficient, and you have awfully big workloads. However, you give up the academic stimulation of being in an academic center. It is a tough discipline in the private practice of medicine to try to stay up to date. Whether going to the CHEST Annual Meeting, reading our journal CHEST, or looking at CHEST education online products, those of us in the clinical practice of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine are more dependent than any group on what our clinical educators write and teach.

How do/did you balance work and your personal life?

We are busy in practice, particularly when taking on volunteer opportunities, and that time comes out of something: time with family, hobbies, it has to come from somewhere. But it is not unique to those of us in medicine. My daughter is a 33-year-old mother to a 20-month-old beautiful granddaughter of ours and is pregnant with another child, and she and her husband both work full time. Our son and his wife also both work and must find ways to balance work/life issues. So work-life balance, particularly in today’s world, is more difficult than ever for everyone. I am blessed that my wife is the daughter of a general surgeon, and she understood a little bit about stressors in a physician’s life – sometimes she seems to understand more than others—she is a unique person. Work-life balance is all about priorities – our priority was our family. We spent a ton of time with our children, great vacations, rarely missed a program or ballgame (there were lots of them), and frequently that involved going to work early in the morning, coming home early in the evening, and going back to the hospital to finish up late at night. A lot of being a good parent is being lucky. We either did a lot of things right, or were lucky, or a combination of both, because I think our kids turned out pretty darn well.

What has been your favorite project throughout your involvement with CHEST?

Early in my days as a member of CHEST, a mentor of mine from training at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Doug Gracey, gave me the opportunity to join the CHEST Government Relations Committee, which he chaired. After a few years, I was given the opportunity to serve as its Chair. We became heavily involved in the tobacco wars, as some people called them. Our Attorney General in Mississippi at the time, Mike Moore, and a plaintiff’s attorney in Mississippi, Dick Scruggs, whom I knew from some work I had done from the defense side of asbestos litigation, took a lead role in the Attorney General’s Master Settlement - a group of attorney generals suing the tobacco industry (basically, state’s Medicaid was suing the tobacco industry for reimbursement of funds). It was a completely different approach. The tobacco industry turned its nose up at it at first – they did not think it had a chance to fly, but it did. CHEST got involved early on, and then a big a group of people, including Tobacco Free Kids, the American Cancer Society, and many others in the public health space, got involved. CHEST represented the public health community during part of the negotiations that led to the Attorney General’s Master Settlement. We should be very proud of the role CHEST played in this critical public health effort. If I can look back at my time spent in CHEST leadership, and see it as fondly as I do when I look back at my time just being a part of our CHEST Foundation, I will feel incredibly fulfilled.

What made you want to be President of CHEST?

I believe it is always important to give back to the people who gave you something. CHEST has given me a ton over the last 36 years, so giving back to CHEST is easy.

What are you looking forward to as President of CHEST?

On a personal level, I am looking forward to what we are doing right now, meeting new people, and learning from young people.

Because of my background and upbringing, I have a passion for diversity and inclusion; I think we need to continue to talk about, learn about, care about, be open about, and be transparent about diversity of thought, inclusion, and care disparity. The word “diversity” means something different to every person, and, for that, we have to have respect.

As Dr. Studdard prepares to take on his new role in CHEST leadership this October, he is optimistic about what the future will bring and about the things that he will learn. He considers himself incredibly lucky to be in the position that he is in, and he values each relationship he has made during his involvement with CHEST. He is looking forward to all that is in store during his time as President. He left us with a quote from Wyatt Cooper:

“The only immortality we can be sure of is that part of ourselves we invest in others—the contribution we make to the totality of man, the knowledge we have shared, the truths we have found, the causes we have served, the lessons we have lived.”

John Studdard, MD, FCCP, has been a member of the American College of Chest Physicians for 36 years, and, this November, he will be inaugurated as CHEST President. This will not be Dr. Studdard’s first time in a presidential role for CHEST, as he served as CHEST Foundation President in 2013 and 2014. Currently, Dr. Studdard serves as a pulmonologist at Jackson Pulmonary in Jackson, Mississippi. Being a physician and being as heavily involved with an organization as Dr. Studdard is takes a lot of prioritizing, hard work, and dedication. Get to know CHEST’s new President through this interview.

Born and raised in Mississippi, Dr. Studdard says there were four factors that inspired him to become a physician:

1. I have always loved people and working with them, and I always admired the respect that physicians received in my community.

3. I am competitive and decided if it was going to be hard to get into medical school, then I wanted to go to medical school.

4. My dad always told my brother and me that we would be doctors when we grew up, because we were going to be our own boss. I have been in private practice for 36 years, and that is not the case, not if you are doing it right. I obviously love medicine, and my dad was great in that he paid for our education…but he called the shots.

What are some of the biggest challenges you have encountered throughout your career?

Private practice makes you gain more independence and autonomy; you have to become more agile, more efficient, and you have awfully big workloads. However, you give up the academic stimulation of being in an academic center. It is a tough discipline in the private practice of medicine to try to stay up to date. Whether going to the CHEST Annual Meeting, reading our journal CHEST, or looking at CHEST education online products, those of us in the clinical practice of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine are more dependent than any group on what our clinical educators write and teach.

How do/did you balance work and your personal life?

We are busy in practice, particularly when taking on volunteer opportunities, and that time comes out of something: time with family, hobbies, it has to come from somewhere. But it is not unique to those of us in medicine. My daughter is a 33-year-old mother to a 20-month-old beautiful granddaughter of ours and is pregnant with another child, and she and her husband both work full time. Our son and his wife also both work and must find ways to balance work/life issues. So work-life balance, particularly in today’s world, is more difficult than ever for everyone. I am blessed that my wife is the daughter of a general surgeon, and she understood a little bit about stressors in a physician’s life – sometimes she seems to understand more than others—she is a unique person. Work-life balance is all about priorities – our priority was our family. We spent a ton of time with our children, great vacations, rarely missed a program or ballgame (there were lots of them), and frequently that involved going to work early in the morning, coming home early in the evening, and going back to the hospital to finish up late at night. A lot of being a good parent is being lucky. We either did a lot of things right, or were lucky, or a combination of both, because I think our kids turned out pretty darn well.

What has been your favorite project throughout your involvement with CHEST?

Early in my days as a member of CHEST, a mentor of mine from training at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Doug Gracey, gave me the opportunity to join the CHEST Government Relations Committee, which he chaired. After a few years, I was given the opportunity to serve as its Chair. We became heavily involved in the tobacco wars, as some people called them. Our Attorney General in Mississippi at the time, Mike Moore, and a plaintiff’s attorney in Mississippi, Dick Scruggs, whom I knew from some work I had done from the defense side of asbestos litigation, took a lead role in the Attorney General’s Master Settlement - a group of attorney generals suing the tobacco industry (basically, state’s Medicaid was suing the tobacco industry for reimbursement of funds). It was a completely different approach. The tobacco industry turned its nose up at it at first – they did not think it had a chance to fly, but it did. CHEST got involved early on, and then a big a group of people, including Tobacco Free Kids, the American Cancer Society, and many others in the public health space, got involved. CHEST represented the public health community during part of the negotiations that led to the Attorney General’s Master Settlement. We should be very proud of the role CHEST played in this critical public health effort. If I can look back at my time spent in CHEST leadership, and see it as fondly as I do when I look back at my time just being a part of our CHEST Foundation, I will feel incredibly fulfilled.

What made you want to be President of CHEST?

I believe it is always important to give back to the people who gave you something. CHEST has given me a ton over the last 36 years, so giving back to CHEST is easy.

What are you looking forward to as President of CHEST?

On a personal level, I am looking forward to what we are doing right now, meeting new people, and learning from young people.

Because of my background and upbringing, I have a passion for diversity and inclusion; I think we need to continue to talk about, learn about, care about, be open about, and be transparent about diversity of thought, inclusion, and care disparity. The word “diversity” means something different to every person, and, for that, we have to have respect.

As Dr. Studdard prepares to take on his new role in CHEST leadership this October, he is optimistic about what the future will bring and about the things that he will learn. He considers himself incredibly lucky to be in the position that he is in, and he values each relationship he has made during his involvement with CHEST. He is looking forward to all that is in store during his time as President. He left us with a quote from Wyatt Cooper:

“The only immortality we can be sure of is that part of ourselves we invest in others—the contribution we make to the totality of man, the knowledge we have shared, the truths we have found, the causes we have served, the lessons we have lived.”

John Studdard, MD, FCCP, has been a member of the American College of Chest Physicians for 36 years, and, this November, he will be inaugurated as CHEST President. This will not be Dr. Studdard’s first time in a presidential role for CHEST, as he served as CHEST Foundation President in 2013 and 2014. Currently, Dr. Studdard serves as a pulmonologist at Jackson Pulmonary in Jackson, Mississippi. Being a physician and being as heavily involved with an organization as Dr. Studdard is takes a lot of prioritizing, hard work, and dedication. Get to know CHEST’s new President through this interview.

Born and raised in Mississippi, Dr. Studdard says there were four factors that inspired him to become a physician:

1. I have always loved people and working with them, and I always admired the respect that physicians received in my community.

3. I am competitive and decided if it was going to be hard to get into medical school, then I wanted to go to medical school.

4. My dad always told my brother and me that we would be doctors when we grew up, because we were going to be our own boss. I have been in private practice for 36 years, and that is not the case, not if you are doing it right. I obviously love medicine, and my dad was great in that he paid for our education…but he called the shots.

What are some of the biggest challenges you have encountered throughout your career?

Private practice makes you gain more independence and autonomy; you have to become more agile, more efficient, and you have awfully big workloads. However, you give up the academic stimulation of being in an academic center. It is a tough discipline in the private practice of medicine to try to stay up to date. Whether going to the CHEST Annual Meeting, reading our journal CHEST, or looking at CHEST education online products, those of us in the clinical practice of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine are more dependent than any group on what our clinical educators write and teach.

How do/did you balance work and your personal life?

We are busy in practice, particularly when taking on volunteer opportunities, and that time comes out of something: time with family, hobbies, it has to come from somewhere. But it is not unique to those of us in medicine. My daughter is a 33-year-old mother to a 20-month-old beautiful granddaughter of ours and is pregnant with another child, and she and her husband both work full time. Our son and his wife also both work and must find ways to balance work/life issues. So work-life balance, particularly in today’s world, is more difficult than ever for everyone. I am blessed that my wife is the daughter of a general surgeon, and she understood a little bit about stressors in a physician’s life – sometimes she seems to understand more than others—she is a unique person. Work-life balance is all about priorities – our priority was our family. We spent a ton of time with our children, great vacations, rarely missed a program or ballgame (there were lots of them), and frequently that involved going to work early in the morning, coming home early in the evening, and going back to the hospital to finish up late at night. A lot of being a good parent is being lucky. We either did a lot of things right, or were lucky, or a combination of both, because I think our kids turned out pretty darn well.

What has been your favorite project throughout your involvement with CHEST?

Early in my days as a member of CHEST, a mentor of mine from training at the Mayo Clinic, Dr. Doug Gracey, gave me the opportunity to join the CHEST Government Relations Committee, which he chaired. After a few years, I was given the opportunity to serve as its Chair. We became heavily involved in the tobacco wars, as some people called them. Our Attorney General in Mississippi at the time, Mike Moore, and a plaintiff’s attorney in Mississippi, Dick Scruggs, whom I knew from some work I had done from the defense side of asbestos litigation, took a lead role in the Attorney General’s Master Settlement - a group of attorney generals suing the tobacco industry (basically, state’s Medicaid was suing the tobacco industry for reimbursement of funds). It was a completely different approach. The tobacco industry turned its nose up at it at first – they did not think it had a chance to fly, but it did. CHEST got involved early on, and then a big a group of people, including Tobacco Free Kids, the American Cancer Society, and many others in the public health space, got involved. CHEST represented the public health community during part of the negotiations that led to the Attorney General’s Master Settlement. We should be very proud of the role CHEST played in this critical public health effort. If I can look back at my time spent in CHEST leadership, and see it as fondly as I do when I look back at my time just being a part of our CHEST Foundation, I will feel incredibly fulfilled.

What made you want to be President of CHEST?

I believe it is always important to give back to the people who gave you something. CHEST has given me a ton over the last 36 years, so giving back to CHEST is easy.

What are you looking forward to as President of CHEST?

On a personal level, I am looking forward to what we are doing right now, meeting new people, and learning from young people.

Because of my background and upbringing, I have a passion for diversity and inclusion; I think we need to continue to talk about, learn about, care about, be open about, and be transparent about diversity of thought, inclusion, and care disparity. The word “diversity” means something different to every person, and, for that, we have to have respect.

As Dr. Studdard prepares to take on his new role in CHEST leadership this October, he is optimistic about what the future will bring and about the things that he will learn. He considers himself incredibly lucky to be in the position that he is in, and he values each relationship he has made during his involvement with CHEST. He is looking forward to all that is in store during his time as President. He left us with a quote from Wyatt Cooper:

“The only immortality we can be sure of is that part of ourselves we invest in others—the contribution we make to the totality of man, the knowledge we have shared, the truths we have found, the causes we have served, the lessons we have lived.”

Connect with the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2017

Be sure to check out our ever-growing presence at CHEST 2017, showcasing the numerous ways we support CHEST members, patients, and the community. Have time for a break or interested in networking with leaders in CHEST medicine? Stop by one of our many open invitation activities listed below to learn more about how the CHEST Foundation can support you in your efforts to champion lung health through clinical research grants, community service, and patient education.

SATURDAY OCTOBER 28

2:00 PM – 4:00 PM (Open Invitation)

Nathan Phillips Square

100 Queen St W, Toronto, ON M5H 2N2, Canada

SUNDAY OCTOBER 29

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

3:15 PM - 4:15 PM

Foundation Session: Severe Asthma Care at Its Best: Shared Decision Making

Convention Center, 716A

4:30 PM - 5:30 PM

Foundation Session: No Money, No Mission: Tips for Getting Your Grant Funded

Convention Center, 716B

MONDAY OCTOBER 30

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Convention Center, 803B

8:45 AM – 10:00 AM

Opening Session/CHEST Foundation

Awards Convocation

Convention Center, Hall G, Level 800

6:30 PM - 8:00 PM

Boehringer Ingelheim and CHEST Foundation Patient Engagement Summit

Sheraton, Grand Ballroom Centre

8:00 PM – 10:00 PM

Young Professionals Reception

(RSVP chestfoundation.org/youngprofessionals)

225 Richmond St W Suite 100

Toronto, ON M5V 1W2, Canada

TUESDAY OCTOBER 31

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 1

9:00 AM - 12:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

ADD YOUR VOICE

and champion lung health at the Actelion Booth #1322. For every addition to the graffiti wall, Actelion will donate $25 to the CHEST Foundation.

Thank you for your support of the CHEST Foundation and our mission of championing lung health!

Be sure to check out our ever-growing presence at CHEST 2017, showcasing the numerous ways we support CHEST members, patients, and the community. Have time for a break or interested in networking with leaders in CHEST medicine? Stop by one of our many open invitation activities listed below to learn more about how the CHEST Foundation can support you in your efforts to champion lung health through clinical research grants, community service, and patient education.

SATURDAY OCTOBER 28

2:00 PM – 4:00 PM (Open Invitation)

Nathan Phillips Square

100 Queen St W, Toronto, ON M5H 2N2, Canada

SUNDAY OCTOBER 29

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

3:15 PM - 4:15 PM

Foundation Session: Severe Asthma Care at Its Best: Shared Decision Making

Convention Center, 716A

4:30 PM - 5:30 PM

Foundation Session: No Money, No Mission: Tips for Getting Your Grant Funded

Convention Center, 716B

MONDAY OCTOBER 30

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Convention Center, 803B

8:45 AM – 10:00 AM

Opening Session/CHEST Foundation

Awards Convocation

Convention Center, Hall G, Level 800

6:30 PM - 8:00 PM

Boehringer Ingelheim and CHEST Foundation Patient Engagement Summit

Sheraton, Grand Ballroom Centre

8:00 PM – 10:00 PM

Young Professionals Reception

(RSVP chestfoundation.org/youngprofessionals)

225 Richmond St W Suite 100

Toronto, ON M5V 1W2, Canada

TUESDAY OCTOBER 31

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 1

9:00 AM - 12:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

ADD YOUR VOICE

and champion lung health at the Actelion Booth #1322. For every addition to the graffiti wall, Actelion will donate $25 to the CHEST Foundation.

Thank you for your support of the CHEST Foundation and our mission of championing lung health!

Be sure to check out our ever-growing presence at CHEST 2017, showcasing the numerous ways we support CHEST members, patients, and the community. Have time for a break or interested in networking with leaders in CHEST medicine? Stop by one of our many open invitation activities listed below to learn more about how the CHEST Foundation can support you in your efforts to champion lung health through clinical research grants, community service, and patient education.

SATURDAY OCTOBER 28

2:00 PM – 4:00 PM (Open Invitation)

Nathan Phillips Square

100 Queen St W, Toronto, ON M5H 2N2, Canada

SUNDAY OCTOBER 29

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

3:15 PM - 4:15 PM

Foundation Session: Severe Asthma Care at Its Best: Shared Decision Making

Convention Center, 716A

4:30 PM - 5:30 PM

Foundation Session: No Money, No Mission: Tips for Getting Your Grant Funded

Convention Center, 716B

MONDAY OCTOBER 30

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Convention Center, 803B

8:45 AM – 10:00 AM

Opening Session/CHEST Foundation

Awards Convocation

Convention Center, Hall G, Level 800

6:30 PM - 8:00 PM

Boehringer Ingelheim and CHEST Foundation Patient Engagement Summit

Sheraton, Grand Ballroom Centre

8:00 PM – 10:00 PM

Young Professionals Reception

(RSVP chestfoundation.org/youngprofessionals)

225 Richmond St W Suite 100

Toronto, ON M5V 1W2, Canada

TUESDAY OCTOBER 31

9:00 AM - 5:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 1

9:00 AM - 12:00 PM

Donor Lounge

Convention Center, 803B

ADD YOUR VOICE

and champion lung health at the Actelion Booth #1322. For every addition to the graffiti wall, Actelion will donate $25 to the CHEST Foundation.

Thank you for your support of the CHEST Foundation and our mission of championing lung health!

Can we stop worrying about the age of blood?

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Blood transfusions are common in critically ill patients; two in five adults admitted to an ICU receive at least one transfusion during their hospitalization (Corwin HL, et al. Crit Care Med. 2004;32[1]:39). Recently, there has been growing concern about the potential dangers involved with prolonged blood storage. Several provocative observational and retrospective studies found that prolonged storage time (ie, the age of the blood being transfused) negatively affects clinical outcomes (Wang D, et al. Transfusion. 2012;52[6]:1184). But now, some newly published trials on blood transfusion practice, including one published in late September 2017 (Cooper DJ, et al. N Engl J Med. Published online, September 27, 2017) seem to debunk much of this literature. Was all of the concern about age of blood overblown?

The appeal of “fresh” blood is intuitive. As consumers, we’re conditioned that the fresher the better. Fresh food tastes best. Carbonated beverages go “flat” over time. The newest iPhone® device is superior to your old one. So, of course, it follows that fresh blood is also better for your health than older blood.

But, in order to have a viable transfusion service, blood has to be stored. Blood is a scarce resource, and blood banks need to keep an adequate supply on hand for expected clinical necessities, as well as for emergencies. Donors can’t be on standby, waiting in the hospital to provide immediate whole blood transfusion. Also, blood needs to be tested for infections and for potential interactions with the patient, and whole blood must be broken down into individual components for transfusion. All of this requires time and storage.

In a randomized study of 100 critically ill adults supported by mechanical ventilation, 50 were randomized to receive “fresh” blood (median storage age 4 days, interquartile range 3-5 days) and 50 were randomized to receive “standard” blood (median storage age 26.5 days, interquartile range 21-36 days) (Kor DJ, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185[8]:842). The primary outcome was gas exchange, as prolonged storage of red blood cells could potentially lead to an increased inflammatory response in patients. However, the authors found no difference in gas exchange between the two groups, and there were no differences in immunologic function or coagulation status.

The ABLE (Age of Blood Evaluation) trial was a randomized, blinded trial of transfusion practices in critically ill patients (Lacroix J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410). In 64 centers in Canada and Europe, 2,430 critically ill adults were randomized to receive either “fresh” blood (mean storage age 6.1 ± 4.9 days) or “standard” blood (mean storage age 22.0 ± 8.4 days). The primary outcome was 90-day mortality, with a power of 90% to detect a 5% change in mortality between the two groups. The investigators found no statistically significant difference in 90-day mortality between the “fresh” and “standard” groups (37% vs 35.3%; hazard ratio 1.1; 95% CI 0.9 – 1.2). Additionally, there were no differences in secondary outcomes, including multiorgan system dysfunction, duration of supportive care, or development of nosocomial infections.

The INFORM (Informing Fresh versus Old Red Cell Management) trial was a randomized study of patients hospitalized in six centers in Canada, Australia, Israel, and the United States (Heddle NM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375[2]:1937). A total of 24,736 patients received transfusions with either “fresh” blood (median storage age 11 days) or “standard” blood (median storage age 23 days). The primary outcome was in-hospital death, with a 90% power to detect a 15% lower relative risk. When comparing the 8,215 patients who received “fresh” blood and the 16,521 patients who received “standard” blood, the authors found no difference in mortality between the two groups (9.1% vs 8.8%; odds ratio 1.04; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.14). Furthermore, there were no differences in outcomes in the high-risk subgroups that included patients with cancer, patients in the ICU, and patients undergoing cardiovascular surgery.

A meta-analysis examined 12 trials of patients who received “fresh” blood compared with those who received “older” or “standard” blood (Alexander PE, et al. Blood. 2016;127[4]:400); 5,229 patients were included in these trials, in which “fresh” blood was defined as blood stored for 3 to 10 days and “older” blood was stored for longer durations. There was no difference in mortality between the two groups (relative risk 1.04; 95% CI 0.94 - 1.14), and no difference in adverse events (relative risk 1.02; 95% CI 0.91 - 1.14). However, perhaps surprisingly, “fresh” blood was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial infections (relative risk 1.09; 95% CI 1.00 - 1.18).

So, can we stop worrying about the age of the blood that we are about to transfuse? Probably. Taken together, these studies suggest that differences in the duration of red blood cell storage allowed within current US FDA standards aren’t clinically relevant, even in critically ill patients. At least, for now, the current practices for age of blood and duration of storage appear unrelated to adverse clinical outcomes.

Dr. Carroll is Professor of Pediatrics, University of Connecticut, Division of Critical Care, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

This Month in CHEST Editor’s Picks

Changes to CPT® codes coming January 2018

There will be a number of changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes of interest to pulmonary/critical care providers in January 2018. A thorough understanding of these changes is important for appropriate coding and reimbursement for the services described by these codes.

There are two changes in the CPT codes for bronchoscopy involving 31645 and 31646. CPT code 31645 describes a therapeutic bronchoscopy, eg, removal of viscous, copious or tenacious secretions from the airway. It had previously included wording that suggested it was used for abscess drainage, and this has been removed. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is repeated during the same hospital stay, then CPT code 31646 should be utilized. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is performed in the non-hospital setting and later repeated, then CPT code 31645 would be used for both procedures.

CPT code 94620 Pulmonary stress testing; simple (eg, 6-minute walk test, prolonged exercise test for bronchospasm with pre- and post-spirometry and oximetry) has been deleted and replaced by two new codes. CPT code 94617 Exercise test for bronchospasm, including pre- and postspirometry, electrocardiographic recording(s), and pulse oximetry describes the procedure used to assess for exercise-induced bronchospasm. CPT code 94618 Pulmonary stress testing (eg, 6-minute walk test), including measurement of heart rate, oximetry, and oxygen titration, when performed, describes the typical simple pulmonary stress test. After January 1, 2018, if CPT code 94620 is used, the claim will be denied. CPT code 94621 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, including measurements of minute ventilation, CO2 production, O2 uptake, and electrocardiographic recordings has been reworded to better describe the procedure of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Additionally, there are numerous parentheticals appended that list the CPT codes that may not be used in conjunction with 94617, 94618, and 94621. Please refer to the 2018 CPT manual for further information on these exclusions.

There will be a number of changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes of interest to pulmonary/critical care providers in January 2018. A thorough understanding of these changes is important for appropriate coding and reimbursement for the services described by these codes.

There are two changes in the CPT codes for bronchoscopy involving 31645 and 31646. CPT code 31645 describes a therapeutic bronchoscopy, eg, removal of viscous, copious or tenacious secretions from the airway. It had previously included wording that suggested it was used for abscess drainage, and this has been removed. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is repeated during the same hospital stay, then CPT code 31646 should be utilized. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is performed in the non-hospital setting and later repeated, then CPT code 31645 would be used for both procedures.

CPT code 94620 Pulmonary stress testing; simple (eg, 6-minute walk test, prolonged exercise test for bronchospasm with pre- and post-spirometry and oximetry) has been deleted and replaced by two new codes. CPT code 94617 Exercise test for bronchospasm, including pre- and postspirometry, electrocardiographic recording(s), and pulse oximetry describes the procedure used to assess for exercise-induced bronchospasm. CPT code 94618 Pulmonary stress testing (eg, 6-minute walk test), including measurement of heart rate, oximetry, and oxygen titration, when performed, describes the typical simple pulmonary stress test. After January 1, 2018, if CPT code 94620 is used, the claim will be denied. CPT code 94621 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, including measurements of minute ventilation, CO2 production, O2 uptake, and electrocardiographic recordings has been reworded to better describe the procedure of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Additionally, there are numerous parentheticals appended that list the CPT codes that may not be used in conjunction with 94617, 94618, and 94621. Please refer to the 2018 CPT manual for further information on these exclusions.

There will be a number of changes to Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes of interest to pulmonary/critical care providers in January 2018. A thorough understanding of these changes is important for appropriate coding and reimbursement for the services described by these codes.

There are two changes in the CPT codes for bronchoscopy involving 31645 and 31646. CPT code 31645 describes a therapeutic bronchoscopy, eg, removal of viscous, copious or tenacious secretions from the airway. It had previously included wording that suggested it was used for abscess drainage, and this has been removed. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is repeated during the same hospital stay, then CPT code 31646 should be utilized. If a therapeutic bronchoscopy procedure is performed in the non-hospital setting and later repeated, then CPT code 31645 would be used for both procedures.

CPT code 94620 Pulmonary stress testing; simple (eg, 6-minute walk test, prolonged exercise test for bronchospasm with pre- and post-spirometry and oximetry) has been deleted and replaced by two new codes. CPT code 94617 Exercise test for bronchospasm, including pre- and postspirometry, electrocardiographic recording(s), and pulse oximetry describes the procedure used to assess for exercise-induced bronchospasm. CPT code 94618 Pulmonary stress testing (eg, 6-minute walk test), including measurement of heart rate, oximetry, and oxygen titration, when performed, describes the typical simple pulmonary stress test. After January 1, 2018, if CPT code 94620 is used, the claim will be denied. CPT code 94621 Cardiopulmonary exercise testing, including measurements of minute ventilation, CO2 production, O2 uptake, and electrocardiographic recordings has been reworded to better describe the procedure of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Additionally, there are numerous parentheticals appended that list the CPT codes that may not be used in conjunction with 94617, 94618, and 94621. Please refer to the 2018 CPT manual for further information on these exclusions.

Sleep Strategies

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

The definition of mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has varied over the years depending upon several factors, but based upon all definitions, it is highly prevalent. Depending upon presence of symptoms and gender, the prevalence may be as high 28% in men and 26% in women. (Young et al. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230).

Typically, a combination of symptoms and frequency of respiratory events is required to make the diagnosis. Based upon the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3rd edition (ICSD-3), the threshold apnea hypopnea index (AHI) for diagnosis depends upon the presence or absence of symptoms. If an individual has no symptoms, an AHI of 15 events per hour or more is required to make a diagnosis of OSA. However, there are several concerns about whether or not an individual may be “symptomatic.” This is most relevant when driving privileges may be at risk, such as with a commercial drivers’ licensing.

The presence of other comorbid disease can be used as criteria, including hypertension, mood disorder, cognitive dysfunction, coronary artery disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. If no signs, symptoms, or comorbid diseases are present, then an AHI greater than 15 events per hour or more is required to make the diagnosis of OSA (Chowdrui et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37).

There is still debate regarding the association of mild OSA and cardiovascular disease and whether treatment may prevent or reduce cardiovascular outcomes. The four main clinical outcomes typically reported are hypertension, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and arrhythmias.

A large clinical cohort of patients referred for sleep studies showed no association of mild OSA with different composite outcomes. Kendzerska and colleagues evaluated a composite outcome (myocardial infarction, stroke, CHF, revascularization procedures, or death from any cause) during a median follow-up of 68 months. No association of mild OSA with the composite cardiovascular endpoint was identified compared with those without OSA (Kendzerska et al. PLoS Med. 2014;11[2]:e1001599). Only one population-based study (MrOS Sleep Study) looked at the association between mild OSA and nocturnal arrhythmias in elderly men. The study did not find an increased risk for atrial fibrillation or complex ventricular ectopy in patients with mild OSA vs no OSA (Mehra et al. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1147).

Several cohort studies have reported mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular mortality. In the 18-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Cohort Study, it was found that mild OSA was not associated with cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 0.7–4.9). All-cause mortality was also not significantly increased in the mild OSA group compared with the no-OSA group in the Wisconsin cohort after 8 years of follow-up (adjusted HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.8–2.8). In summary, compared with subjects without OSA, available evidence from population-based longitudinal studies indicates that mild OSA is not associated with increased cardiovascular or all-cause mortality.

Does treatment of mild OSA vs no treatment change cardiovascular or mortality outcomes? This is still debated with no definitive answer. There have been several studies that have examined different therapies for OSA to reduce cardiovascular events. Typical events include coronary artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, arrhythmias, and cardiovascular disease-related mortality. However, most studies have examined cohorts with moderate to severe OSA with limited evaluation in the mild OSA category.

An observational study evaluated the effects of CPAP specifically in patients with mild OSA. There was no significant difference in the risk of developing hypertension among those patients ineligible for CPAP therapy, active on therapy, or those who declined therapy (Marin et al. JAMA. 2012; 307:2169). In contrast, a retrospective longitudinal cohort with normal blood pressure at baseline (mild OSA without preexisting cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia) did show decrease in mean arterial blood pressure of 2 mm Hg in the treatment group (Jaimchariyatam et al. Sleep Med. 2010;11:837). The MOSAIC trial was a multicenter randomized trial that evaluated the effects of CPAP on cardiac function in minimally symptomatic patients with OSA. The use of CPAP reduced the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale values. However, 6 months of therapy did not change functional or structural parameters measured by echocardiogram or cardiac magnetic resonance scanning in patients with mild to moderate OSA (Craig et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11[9]:967). A single retrospective study reported the effects of CPAP in patients with mild OSA and all-cause mortality. The study compared treatment with patients using CPAP more than 4 hours vs a combined group of nonadherent and those who refused therapy (Hudgel et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:9). There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality in the two groups. However, this study did not analyze the impact of therapy on cardiovascular-specific mortality.

To date, there have been no studies that have evaluated the impact of treatment of mild OSA on cardiovascular events, arrhythmias, or stroke. In addition, there have been no randomized studies assessing treatment of mild OSA on fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. There is inadequate evidence regarding the effect of mild OSA on elevated blood pressure, neurologic cognition, quality of life, and cardiovascular consequences. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of mild OSA on these outcomes.

In summary, mild OSA is a very prevalent disease but the association with hypertension remains unclear and the literature to date suggests no association with other cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, no clear prevention of cardiovascular outcomes with treatment has been proven in the setting of mild OSA.

Dr. Duthuluru is Assistant Professor, Dr. Nazir is Assistant Professor, and Dr. Stevens is Associate Professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

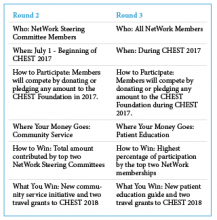

CHEST Foundation NetWorks Challenge

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

The CHEST Foundation is proud to announce the winners of the first round of the 2017 NetWorks Challenge! Our first place winner, Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Disease NetWork, and our second place finisher, Women’s Health NetWork, both receive session time at CHEST 2017 on a topic of their choice and two travel grants to help their NetWork members attend CHEST 2017.

The Women’s Health NetWork was directly behind our first place finishers with more than 90% participation. Their session, “Care of the Critically Ill Pregnant Woman: Balancing Two Patients and Two Lives” will be on Monday, October 30, 1:30

Don’t forget, there is still time to win Round 2 and Round 3 of the NetWorks Challenge.

Learn more about the challenge at chestfoundation.org/networkschallenge.

NetWorks

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).

However, after reviewing the public input and data, the FRA and FMCSA recently announced that there was “not enough information available to support moving forward with a rulemaking action,” and, therefore, they are no longer pursuing the regulation that would require SA screening for truck drivers and train engineers (Federal Register August 2017;49 CFR 391,240,242). See CHEST’s press release at www.chestnet.org/News/Press-Releases/2017/08/American-College-of-Chest-Physicians-Responds-to-DOT-Withdrawal-of-Sleep-Apnea-Screening. The FMCSA endorses existing resources,such as the North American Fatigue Management Program (NAFMP) (www.nafmp.org), which is a web-based program designed to reduce driver fatigue and includes information on SA screening and treatment. The medical examiners, however, will have the ultimate responsibility to screen, diagnose, and treat SA based on their medical knowledge and clinical experience.

Vaishnavi Kundel, MD

NetWork Member

Steering Committee Member

Corrections to previous NetWork articles

July 2017

Clinical Research

Mohsin Ijaz’s name was misspelled.

August 2017

Transplant

The name under Shruti Gadre’s photograph is wrong. It says Dr. Ahya instead of Dr. Gadre.

The authorship of the article at the end of the article is incorrect. It says Vivek Ahya, instead of Shruti Gadre and Marie Budev.

Gender Disparities in Occupational Health

Over the past few decades, the presence of women in the workforce has changed significantly. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, in 2015, 46.8% of the workforce included women compared with 28.6% in 1948. Along with this change, there has been an increased focus on gender disparities in occupational health.

Gender differences in occupational asthma were also seen in snow crab processing plant workers. Women were significantly more likely to have occupational asthma than men. However, they found that overall, women had a greater cumulative exposure to crab allergens, which may be a major contributor to this disparity (Howse et al. Environ Res. 2006;101[2]:163).

Although several occupational health studies are beginning to highlight gender disparities, a major confounding factor is that of occupational segregation, meaning the under-representation of one gender in some jobs and over-representation in others. Differences in jobs and tasks even within the same job title between men and women are often major contributors to gender disparities [WHO Dept of Gender, Women and Health, 2006]. Also, several studies suggest that more women should be included in toxicology and occupational cancer studies, since currently, they have included mostly men (Sorrentino et al. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2016;52[2]:190). Perhaps future studies can improve the overall understanding of these important contributing factors to gender disparities in occupational health.

Krystal Cleven, MD

Fellow-in-Training Member

Does Beta-agonist Therapy With Albuterol Cause Lactic Acidosis?

Cohen and associates (Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:405) suggested that lactic acidosis can occur in at least two different physiologic clinical presentations. Type A occurs when oxygen delivery to the tissues is compromised. Dodda and Spiro (Respir Care. 2012;57[12]:2115) indicated that type A lactic acidosis was due to hypoxemia, as seen in inadequate tissue oxygenation during an exacerbation of asthma. In severe asthma, pulsus paradoxus and air trapping (causing intrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure, or PEEP) served to decrease tissue oxygenation by decreasing cardiac output and venous return, leading to type A lactic acidosis. Bates and associates (Pediatrics. 2014;133[4]:e1087) considered the role of intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVs) when a status asthmaticus patient improved after cessation of beta-agonist therapy. Type B lactic acidosis occurs when lactate production was increased or lactate removal was decreased even when oxygen was delivered to tissue. Amaducci (http://www.emresident.org/gasping-air-albuterol-induced-lactic-acidosis/) explained how high dosages of albuterol, beyond 1 mg/kg, created an increased adrenergic state that, with reduced tissue perfusion, increased glycolysis and pyruvate production, resulting in measurable hyperlactatemia. The authors (Br J Med Pract. 2011;4[2]:a420) noted that lactic acidosis also occurs in acute severe asthma due to inadequate oxygen delivery to the respiratory muscles to meet an elevated oxygen demand or due to fatiguing respiratory muscles. Ganaie and Hughes reported a case of lactic acidosis caused by treatment with salbutamol. Salbutamol is the most commonly used short-acting beta-agonist. Stimulation of beta-adrenergic receptors leads to a variety of metabolic effects, including increase in glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and lipolysis, thus contributing to lactic acidosis. All authors agreed that the mechanism of albuterol-caused lactic acidosis was poorly understood.

Douglas E. Masini, EdD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Withdrawal of OSA Screening Regulation for Commercial Motor Vehicle Operators

Compared with the general US population, the prevalence of sleep apnea (SA) is higher among commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers (Berger et al. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54[8]:1017). Additionally, the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among individuals with SA compared with those without SA (Tregear et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5[6]:573), and treatment of SA is associated with a reduction in this risk (Mahssa et al. Sleep. 2015;38[3]341).