User login

Hospitalists Should Endorse Their Team Members

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

At every opportunity, I position and endorse my colleagues who are or will be participating in my patient’s care by describing their roles and expressing my confidence in their abilities.

Why I Do It

It is vital that our patients feel assured they are being cared for by a high-functioning team of experts. During any given hospital stay, our patients will meet consulting physicians, nurses, therapists, case managers … The list goes on and on. Each person plays a vital part in patients’ care. But it can be difficult for patients to understand every person’s role and to feel assured that each person is highly skilled and aligned with the care plan.

As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to provide a foundation of assuredness and confidence that is a cornerstone of patient experience before our teammates meet patients. When we miss this opportunity, our patients perceive us as a sea of white coats passing in and out of their rooms rather than a cohesive team with their best interests at heart.

How I Do It

Let’s take the example of an elderly patient admitted for a hip fracture after a fall. Alongside the hospitalist will be the orthopedic surgeon, nurse, physical therapist, and case manager, all working toward an optimal outcome. In each case, the hospitalist can choose to provide no information about these team members or to position them for a positive first impression.

Here are the steps to take when positioning colleagues with patients:

- Identify team members and explain their roles.

- Endorse colleagues by expressing honest confidence in their expertise and ability.

- Describe how communication between you and your team members will work.

- Assure the patient that during handoff, your colleagues will be up-to-date and aligned with the plan.

- Tell your patients they are part of a team dedicated to a safe and effective hospitalization.

Mark Shapiro, MD, is medical director for hospital medicine at St. Joseph Health Medical Group in Santa Rosa, Calif., and producer and host of Explore the Space podcast (explorethespaceshow.com).

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

At every opportunity, I position and endorse my colleagues who are or will be participating in my patient’s care by describing their roles and expressing my confidence in their abilities.

Why I Do It

It is vital that our patients feel assured they are being cared for by a high-functioning team of experts. During any given hospital stay, our patients will meet consulting physicians, nurses, therapists, case managers … The list goes on and on. Each person plays a vital part in patients’ care. But it can be difficult for patients to understand every person’s role and to feel assured that each person is highly skilled and aligned with the care plan.

As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to provide a foundation of assuredness and confidence that is a cornerstone of patient experience before our teammates meet patients. When we miss this opportunity, our patients perceive us as a sea of white coats passing in and out of their rooms rather than a cohesive team with their best interests at heart.

How I Do It

Let’s take the example of an elderly patient admitted for a hip fracture after a fall. Alongside the hospitalist will be the orthopedic surgeon, nurse, physical therapist, and case manager, all working toward an optimal outcome. In each case, the hospitalist can choose to provide no information about these team members or to position them for a positive first impression.

Here are the steps to take when positioning colleagues with patients:

- Identify team members and explain their roles.

- Endorse colleagues by expressing honest confidence in their expertise and ability.

- Describe how communication between you and your team members will work.

- Assure the patient that during handoff, your colleagues will be up-to-date and aligned with the plan.

- Tell your patients they are part of a team dedicated to a safe and effective hospitalization.

Mark Shapiro, MD, is medical director for hospital medicine at St. Joseph Health Medical Group in Santa Rosa, Calif., and producer and host of Explore the Space podcast (explorethespaceshow.com).

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

At every opportunity, I position and endorse my colleagues who are or will be participating in my patient’s care by describing their roles and expressing my confidence in their abilities.

Why I Do It

It is vital that our patients feel assured they are being cared for by a high-functioning team of experts. During any given hospital stay, our patients will meet consulting physicians, nurses, therapists, case managers … The list goes on and on. Each person plays a vital part in patients’ care. But it can be difficult for patients to understand every person’s role and to feel assured that each person is highly skilled and aligned with the care plan.

As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to provide a foundation of assuredness and confidence that is a cornerstone of patient experience before our teammates meet patients. When we miss this opportunity, our patients perceive us as a sea of white coats passing in and out of their rooms rather than a cohesive team with their best interests at heart.

How I Do It

Let’s take the example of an elderly patient admitted for a hip fracture after a fall. Alongside the hospitalist will be the orthopedic surgeon, nurse, physical therapist, and case manager, all working toward an optimal outcome. In each case, the hospitalist can choose to provide no information about these team members or to position them for a positive first impression.

Here are the steps to take when positioning colleagues with patients:

- Identify team members and explain their roles.

- Endorse colleagues by expressing honest confidence in their expertise and ability.

- Describe how communication between you and your team members will work.

- Assure the patient that during handoff, your colleagues will be up-to-date and aligned with the plan.

- Tell your patients they are part of a team dedicated to a safe and effective hospitalization.

Mark Shapiro, MD, is medical director for hospital medicine at St. Joseph Health Medical Group in Santa Rosa, Calif., and producer and host of Explore the Space podcast (explorethespaceshow.com).

Use Whiteboards to Enhance Patient-Provider Communication

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

With my team, I use whiteboards as a tool to enhance communication: 1) I introduce myself and my team members, then write our names on the whiteboard paired with an explanation of my role as the attending physician for the hospital medicine service; 2) on a daily basis, I ask the patient and family/support what their primary concerns and goals are and write those on the whiteboard; and 3) I invite the patient and family/support to use the whiteboard to write additional concerns or questions as they arise.

Why I Do It

Hospitals are confusing places. One of our key roles as hospitalists is to coordinate and clarify all of the moving pieces and to communicate clearly to patients and their family that there is someone doing that work on their behalf. The whiteboard can help to accomplish that and to visually indicate “reflective listening.” If I ask patients what their concerns and goals are on a daily basis, I can better address them, and writing those on the whiteboard is a way to visually let patients know I have heard them—and heard them accurately. Finally, as we know from experience at our institution, when patients are invited to write on the whiteboard, they are likely to do so and will often write important information that hasn’t come up during routine rounding.

How I Do It

The key to effectiveness is to build whiteboard use into the clinical workflow and patient conversation rather than create an extra task to complete. I have developed a routine using the whiteboard that is more or less the same for every patient.

Also, whiteboard design can influence the use of the whiteboard as a communication tool. I favor designs that have few prescriptive boxes and more space for writing. I have found whiteboards labeled with a “What are your goals?” section to be helpful.

Patrick Kneeland, MD, is medical director for patient and provider experience and director of the Excellence in Communication Curriculum, University of Colorado Hospital and Clinics.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

With my team, I use whiteboards as a tool to enhance communication: 1) I introduce myself and my team members, then write our names on the whiteboard paired with an explanation of my role as the attending physician for the hospital medicine service; 2) on a daily basis, I ask the patient and family/support what their primary concerns and goals are and write those on the whiteboard; and 3) I invite the patient and family/support to use the whiteboard to write additional concerns or questions as they arise.

Why I Do It

Hospitals are confusing places. One of our key roles as hospitalists is to coordinate and clarify all of the moving pieces and to communicate clearly to patients and their family that there is someone doing that work on their behalf. The whiteboard can help to accomplish that and to visually indicate “reflective listening.” If I ask patients what their concerns and goals are on a daily basis, I can better address them, and writing those on the whiteboard is a way to visually let patients know I have heard them—and heard them accurately. Finally, as we know from experience at our institution, when patients are invited to write on the whiteboard, they are likely to do so and will often write important information that hasn’t come up during routine rounding.

How I Do It

The key to effectiveness is to build whiteboard use into the clinical workflow and patient conversation rather than create an extra task to complete. I have developed a routine using the whiteboard that is more or less the same for every patient.

Also, whiteboard design can influence the use of the whiteboard as a communication tool. I favor designs that have few prescriptive boxes and more space for writing. I have found whiteboards labeled with a “What are your goals?” section to be helpful.

Patrick Kneeland, MD, is medical director for patient and provider experience and director of the Excellence in Communication Curriculum, University of Colorado Hospital and Clinics.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

With my team, I use whiteboards as a tool to enhance communication: 1) I introduce myself and my team members, then write our names on the whiteboard paired with an explanation of my role as the attending physician for the hospital medicine service; 2) on a daily basis, I ask the patient and family/support what their primary concerns and goals are and write those on the whiteboard; and 3) I invite the patient and family/support to use the whiteboard to write additional concerns or questions as they arise.

Why I Do It

Hospitals are confusing places. One of our key roles as hospitalists is to coordinate and clarify all of the moving pieces and to communicate clearly to patients and their family that there is someone doing that work on their behalf. The whiteboard can help to accomplish that and to visually indicate “reflective listening.” If I ask patients what their concerns and goals are on a daily basis, I can better address them, and writing those on the whiteboard is a way to visually let patients know I have heard them—and heard them accurately. Finally, as we know from experience at our institution, when patients are invited to write on the whiteboard, they are likely to do so and will often write important information that hasn’t come up during routine rounding.

How I Do It

The key to effectiveness is to build whiteboard use into the clinical workflow and patient conversation rather than create an extra task to complete. I have developed a routine using the whiteboard that is more or less the same for every patient.

Also, whiteboard design can influence the use of the whiteboard as a communication tool. I favor designs that have few prescriptive boxes and more space for writing. I have found whiteboards labeled with a “What are your goals?” section to be helpful.

Patrick Kneeland, MD, is medical director for patient and provider experience and director of the Excellence in Communication Curriculum, University of Colorado Hospital and Clinics.

How to Better Connect with Patients

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

Before entering a patient’s room, I take a “mindful moment,” a brief mindfulness practice to boost empathy. This is a quick, simple, and effective way for me to rehab my empathy muscle.

Why I Do It

From empathy comes our desire to care about another human being, to connect with them, and to understand and be understood.

Many of the colleagues I talk to about patient experience echo the same sentiment: They feel powerless to change someone else’s experience, which is bundled with the immovable variables of their own perceptions and contexts.

While I believe there is truth to that, we can certainly change our experience, and that is what matters to patients. As my mentor and coach Anya Sophia Mann reminded me recently, “We are not responsible for the patient experience. We are responsible for our own experience, which we then bring to our patients. Your heart connection to your own empathic center is beautifully contagious and will spread to those around you throughout your day.”

How I Do It

We may think that empathy is an innate talent, but the literature supports that it is a skill like any other that can be taught, practiced, and deliberately and consciously turned up and down like the brightness on your smartphone.

A heartfelt patient experience starts with the feeling of connection to our own heart. But we can’t think our way into a feeling. If I let my head lead the way, I shield my heart from participating in true communication with the patient. We are both left without connection, without a sense of purpose, without fulfillment—empty and tired.

For the antidote, I choose to create an experience for my body to feel rather than an idea for my head to think about. Ironically, mindfulness starts not with the mind but with the body and, more precisely, with the breath.

Before entering the patient’s room, usually as I’m rubbing the hand sanitizer between my fingers, I take a deep breath that expands my belly instead of my chest, then I exhale, leaving plenty of time for the complete out breath. Next, I make the choice to be curious about the sensations in my body: “What have I carried with me from my interaction with the previous patient (or the nurse or the driver in front of me during my commute)? Does my jaw feel tight? Where do I feel stuck? Where exactly does that lump in my throat begin and end?”

The instruction here is just to notice without judgment. From that place of noticing, I have done a quick erasing of my emotional whiteboard to create space where I can respond rather than react to what is most important to my patient. I invite you to try these steps and notice what shifts happen for you and your patients. You won’t know it until you try it—and feel it—for yourself.

- Pause long enough to feel the ground supporting you under both feet.

- Take a deep, cleansing belly breath. Exhale fully without added effort.

- Notice, without judgment, the sensations in your body.

- Feel the space created by the melting and releasing of those feelings.

- Bring that feeling of space with you as you begin the conversation with the patient.

Michael Donlin, ACNP-BC, FHM, is an inpatient nurse practitioner for the Department of Medicine, VA Boston Healthcare System.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

Before entering a patient’s room, I take a “mindful moment,” a brief mindfulness practice to boost empathy. This is a quick, simple, and effective way for me to rehab my empathy muscle.

Why I Do It

From empathy comes our desire to care about another human being, to connect with them, and to understand and be understood.

Many of the colleagues I talk to about patient experience echo the same sentiment: They feel powerless to change someone else’s experience, which is bundled with the immovable variables of their own perceptions and contexts.

While I believe there is truth to that, we can certainly change our experience, and that is what matters to patients. As my mentor and coach Anya Sophia Mann reminded me recently, “We are not responsible for the patient experience. We are responsible for our own experience, which we then bring to our patients. Your heart connection to your own empathic center is beautifully contagious and will spread to those around you throughout your day.”

How I Do It

We may think that empathy is an innate talent, but the literature supports that it is a skill like any other that can be taught, practiced, and deliberately and consciously turned up and down like the brightness on your smartphone.

A heartfelt patient experience starts with the feeling of connection to our own heart. But we can’t think our way into a feeling. If I let my head lead the way, I shield my heart from participating in true communication with the patient. We are both left without connection, without a sense of purpose, without fulfillment—empty and tired.

For the antidote, I choose to create an experience for my body to feel rather than an idea for my head to think about. Ironically, mindfulness starts not with the mind but with the body and, more precisely, with the breath.

Before entering the patient’s room, usually as I’m rubbing the hand sanitizer between my fingers, I take a deep breath that expands my belly instead of my chest, then I exhale, leaving plenty of time for the complete out breath. Next, I make the choice to be curious about the sensations in my body: “What have I carried with me from my interaction with the previous patient (or the nurse or the driver in front of me during my commute)? Does my jaw feel tight? Where do I feel stuck? Where exactly does that lump in my throat begin and end?”

The instruction here is just to notice without judgment. From that place of noticing, I have done a quick erasing of my emotional whiteboard to create space where I can respond rather than react to what is most important to my patient. I invite you to try these steps and notice what shifts happen for you and your patients. You won’t know it until you try it—and feel it—for yourself.

- Pause long enough to feel the ground supporting you under both feet.

- Take a deep, cleansing belly breath. Exhale fully without added effort.

- Notice, without judgment, the sensations in your body.

- Feel the space created by the melting and releasing of those feelings.

- Bring that feeling of space with you as you begin the conversation with the patient.

Michael Donlin, ACNP-BC, FHM, is an inpatient nurse practitioner for the Department of Medicine, VA Boston Healthcare System.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

Before entering a patient’s room, I take a “mindful moment,” a brief mindfulness practice to boost empathy. This is a quick, simple, and effective way for me to rehab my empathy muscle.

Why I Do It

From empathy comes our desire to care about another human being, to connect with them, and to understand and be understood.

Many of the colleagues I talk to about patient experience echo the same sentiment: They feel powerless to change someone else’s experience, which is bundled with the immovable variables of their own perceptions and contexts.

While I believe there is truth to that, we can certainly change our experience, and that is what matters to patients. As my mentor and coach Anya Sophia Mann reminded me recently, “We are not responsible for the patient experience. We are responsible for our own experience, which we then bring to our patients. Your heart connection to your own empathic center is beautifully contagious and will spread to those around you throughout your day.”

How I Do It

We may think that empathy is an innate talent, but the literature supports that it is a skill like any other that can be taught, practiced, and deliberately and consciously turned up and down like the brightness on your smartphone.

A heartfelt patient experience starts with the feeling of connection to our own heart. But we can’t think our way into a feeling. If I let my head lead the way, I shield my heart from participating in true communication with the patient. We are both left without connection, without a sense of purpose, without fulfillment—empty and tired.

For the antidote, I choose to create an experience for my body to feel rather than an idea for my head to think about. Ironically, mindfulness starts not with the mind but with the body and, more precisely, with the breath.

Before entering the patient’s room, usually as I’m rubbing the hand sanitizer between my fingers, I take a deep breath that expands my belly instead of my chest, then I exhale, leaving plenty of time for the complete out breath. Next, I make the choice to be curious about the sensations in my body: “What have I carried with me from my interaction with the previous patient (or the nurse or the driver in front of me during my commute)? Does my jaw feel tight? Where do I feel stuck? Where exactly does that lump in my throat begin and end?”

The instruction here is just to notice without judgment. From that place of noticing, I have done a quick erasing of my emotional whiteboard to create space where I can respond rather than react to what is most important to my patient. I invite you to try these steps and notice what shifts happen for you and your patients. You won’t know it until you try it—and feel it—for yourself.

- Pause long enough to feel the ground supporting you under both feet.

- Take a deep, cleansing belly breath. Exhale fully without added effort.

- Notice, without judgment, the sensations in your body.

- Feel the space created by the melting and releasing of those feelings.

- Bring that feeling of space with you as you begin the conversation with the patient.

Michael Donlin, ACNP-BC, FHM, is an inpatient nurse practitioner for the Department of Medicine, VA Boston Healthcare System.

Using Brochures, Business Cards to Make Personal Connection with Patients

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I sit down at patients’ eye level during patient visits and use a team brochure/personal business card for all new patients.

Why I Do It

One of the major concerns expressed by patients is the time spent with them by their provider. Sitting down at patients’ eye level lets them know that you are not in a hurry and you are there to give them whatever time they need. Sitting also causes your patients to perceive that you spent more time with them than if you spent the same amount of time while standing. This practice is not only advocated by patient-care consultants but is something I had reinforced during my firsthand experience as a patient several years ago when I had a surgical procedure. Every time the surgeon came into my hospital room, he sat in the chair, leisurely crossed his legs, and spoke to me from that position while writing in the chart. I knew exactly what he was doing, and it still made a difference to me! It put me more at ease and made me feel that he was there for me, ready to give me whatever time I needed and answer any questions that I had (and I had them). Sitting also puts you on an even level with your patients so they feel that you are talking with them, not down to them. This eases tension, adds comfort and trust to the situation, and is much more engaging.

How I Do It

After I greet patients, I look for a place to sit. If there is a chair, I pull it over to the bedside, sit in a relaxed manner, and continue the visit. If there is no chair in the room, I will sit on the windowsill, the bedside table (I have even been known to lower the bedside tray table and sit on the end with the support post if there is room on it), or whatever I can utilize to physically put myself on patients’ level. As a last resort, as long as there is not an isolatable infection, I will ask permission to sit on the edge of the bed. I make a point of telling them during this process that I am looking for a place to sit and talk so that they know this is my goal.

After the initial conversation and exam, if the patients are new to the service, I walk them through our team brochure and reiterate how we act as their PCP in the hospital and how we communicate with their PCP. I also make a point to show the team photo roster, which personalizes our team to patients, and say, “I also want you to have one of my baseball cards. We call our business cards ‘baseball cards’ because they have our pictures and a lot of ‘stats’ on them: our training, personal interests. That way, you know more about the person who is helping to take care of you.” I almost always see these cards out on patients’ trays or bedside tables on subsequent visits. Patients seem appreciative of the cards and the information. If I see another provider’s baseball card, I will ask patients a question about that provider as a way to continue to foster relations between our patients and our team. The more our patients can relate to us, the more they will trust us and the better their experience will be. TH

Dr. Sharp is a chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at UF Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I sit down at patients’ eye level during patient visits and use a team brochure/personal business card for all new patients.

Why I Do It

One of the major concerns expressed by patients is the time spent with them by their provider. Sitting down at patients’ eye level lets them know that you are not in a hurry and you are there to give them whatever time they need. Sitting also causes your patients to perceive that you spent more time with them than if you spent the same amount of time while standing. This practice is not only advocated by patient-care consultants but is something I had reinforced during my firsthand experience as a patient several years ago when I had a surgical procedure. Every time the surgeon came into my hospital room, he sat in the chair, leisurely crossed his legs, and spoke to me from that position while writing in the chart. I knew exactly what he was doing, and it still made a difference to me! It put me more at ease and made me feel that he was there for me, ready to give me whatever time I needed and answer any questions that I had (and I had them). Sitting also puts you on an even level with your patients so they feel that you are talking with them, not down to them. This eases tension, adds comfort and trust to the situation, and is much more engaging.

How I Do It

After I greet patients, I look for a place to sit. If there is a chair, I pull it over to the bedside, sit in a relaxed manner, and continue the visit. If there is no chair in the room, I will sit on the windowsill, the bedside table (I have even been known to lower the bedside tray table and sit on the end with the support post if there is room on it), or whatever I can utilize to physically put myself on patients’ level. As a last resort, as long as there is not an isolatable infection, I will ask permission to sit on the edge of the bed. I make a point of telling them during this process that I am looking for a place to sit and talk so that they know this is my goal.

After the initial conversation and exam, if the patients are new to the service, I walk them through our team brochure and reiterate how we act as their PCP in the hospital and how we communicate with their PCP. I also make a point to show the team photo roster, which personalizes our team to patients, and say, “I also want you to have one of my baseball cards. We call our business cards ‘baseball cards’ because they have our pictures and a lot of ‘stats’ on them: our training, personal interests. That way, you know more about the person who is helping to take care of you.” I almost always see these cards out on patients’ trays or bedside tables on subsequent visits. Patients seem appreciative of the cards and the information. If I see another provider’s baseball card, I will ask patients a question about that provider as a way to continue to foster relations between our patients and our team. The more our patients can relate to us, the more they will trust us and the better their experience will be. TH

Dr. Sharp is a chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at UF Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I sit down at patients’ eye level during patient visits and use a team brochure/personal business card for all new patients.

Why I Do It

One of the major concerns expressed by patients is the time spent with them by their provider. Sitting down at patients’ eye level lets them know that you are not in a hurry and you are there to give them whatever time they need. Sitting also causes your patients to perceive that you spent more time with them than if you spent the same amount of time while standing. This practice is not only advocated by patient-care consultants but is something I had reinforced during my firsthand experience as a patient several years ago when I had a surgical procedure. Every time the surgeon came into my hospital room, he sat in the chair, leisurely crossed his legs, and spoke to me from that position while writing in the chart. I knew exactly what he was doing, and it still made a difference to me! It put me more at ease and made me feel that he was there for me, ready to give me whatever time I needed and answer any questions that I had (and I had them). Sitting also puts you on an even level with your patients so they feel that you are talking with them, not down to them. This eases tension, adds comfort and trust to the situation, and is much more engaging.

How I Do It

After I greet patients, I look for a place to sit. If there is a chair, I pull it over to the bedside, sit in a relaxed manner, and continue the visit. If there is no chair in the room, I will sit on the windowsill, the bedside table (I have even been known to lower the bedside tray table and sit on the end with the support post if there is room on it), or whatever I can utilize to physically put myself on patients’ level. As a last resort, as long as there is not an isolatable infection, I will ask permission to sit on the edge of the bed. I make a point of telling them during this process that I am looking for a place to sit and talk so that they know this is my goal.

After the initial conversation and exam, if the patients are new to the service, I walk them through our team brochure and reiterate how we act as their PCP in the hospital and how we communicate with their PCP. I also make a point to show the team photo roster, which personalizes our team to patients, and say, “I also want you to have one of my baseball cards. We call our business cards ‘baseball cards’ because they have our pictures and a lot of ‘stats’ on them: our training, personal interests. That way, you know more about the person who is helping to take care of you.” I almost always see these cards out on patients’ trays or bedside tables on subsequent visits. Patients seem appreciative of the cards and the information. If I see another provider’s baseball card, I will ask patients a question about that provider as a way to continue to foster relations between our patients and our team. The more our patients can relate to us, the more they will trust us and the better their experience will be. TH

Dr. Sharp is a chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at UF Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

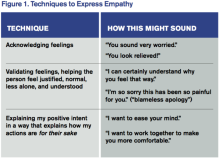

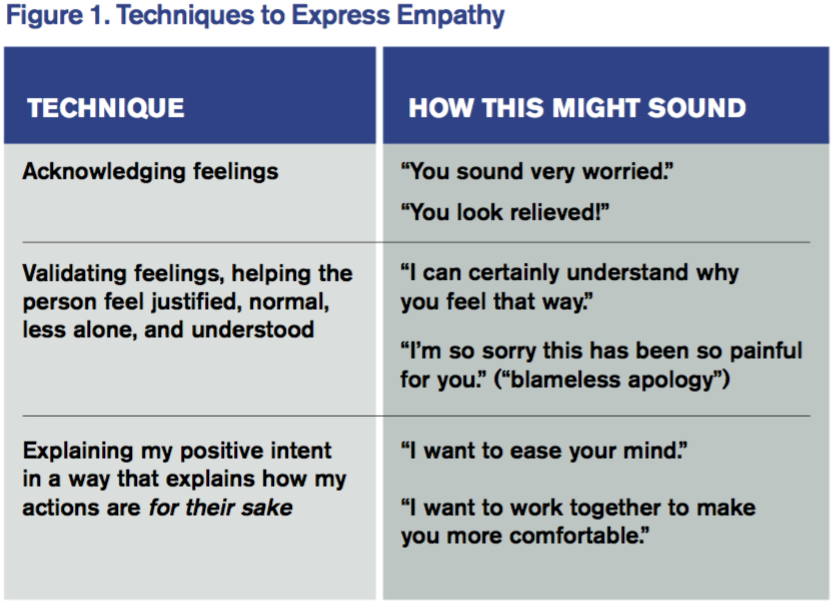

Tips for Communicating with Empathy

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

In interactions with patients and families, I make sure I communicate with empathy. By communicating with empathy, I mean not only listening for and understanding a patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspective but also communicating this understanding with my intention to help.

Why I Do It

Time constraints, endless to-do lists, and racing minds can eclipse empathic, attentive, and personalized care. When empathy is missing from the patient-clinician relationship, patients and clinicians suffer. Patients feel disengaged from their clinician; they remain anxious and lose trust. And physicians miss out on the gratification of feeling connected with patients and on achieving the best possible patient engagement and outcomes.

Physician empathy is associated with not only higher levels of patient satisfaction and survey scores but also with patient engagement, adherence to care plans, and positive health outcomes as well as physician job satisfaction.1–3

How I Do It

I start with mindfulness. I sustain eye contact, sit eye to eye, and give the person my undivided attention, listening to their words and nonverbal behavior—without judgment.

Then I draw on several techniques that express empathy. My favorites are these:

On a Personal Note

Albert Schweitzer said, “At times, our own light goes out and is rekindled by a spark from another person. Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.” Communicating with empathy, to me, is the spark that rekindles the lights of patients, families, and colleagues in our relationships with them. TH

Wendy Leebov is founder and partner in Language of Caring, LLC, author of The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians, and developer of the Language of Caring for Physicians web-based learning program. Reach her at [email protected].

References

- Leebov W, Rotering C. The Language of Caring Guide for Physicians: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care. 2nd ed. Language of Caring, LLC; 2015.

- Butterfield S. New research links empathy to outcomes. ACP Internist website. Available at: http://www.acpinternist.org/archives/2013/03/empathy.htm. Accessed July 8, 2016.

- Hojat M, Louis D, Maio V, Gonnella J. Empathy and health care quality. Am J Medical Quality. 2013;28(1):6-7.

Use the Teach-Back Method to Confirm Patient Understanding

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I use the teach-back method to confirm my patients’ understanding.

Why I Do It

Teach-back allows me to address my patients’ uncertainty about the plan and clarify any misunderstandings.

As doctors, one of our most important jobs is explaining in ways our patients understand. It doesn’t matter how brilliant our treatment plan is if our patients do not understand it. We all want to feel like we’re making a difference in our patients’ lives. Yet it’s hard for our patients to do what we recommend if they don’t understand.

Unfortunately, many patients are too embarrassed to ask questions, or they simply do not know what to ask. Patients will also say they understand everything even when they do not because they fear appearing uneducated.

This is why the teach-back method is so valuable. The teach-back method allows you to better assess your patients’ understanding of their medical problems. It allows you to uncover and clarify any misunderstandings your patients may have about the plan. It also helps you to engage in a more collaborative relationship with your patients.

How I Do It

Teach-back helps me to test my effectiveness as a teacher by allowing me to assess whether my patient understands; if not, I explain in a different way.

One of the common mistakes clinicians make when assessing for understanding is asking, “Do you have any questions?” or “Does this make sense?” The problem with these questions is that they are closed-ended. The only responses are yes or no. Your patients may say they understand even when they do not. In reality, it does not matter how brilliant your treatment plans are if patients do not follow them because they do not understand.

Teach-back encourages the doctor to check for understanding by using open-ended instead of closed-ended questions.

Example one: “This is a new diagnosis for you, so I want to make sure you understand. Will you tell me in your own words what congestive heart failure is?”

Example two: “I want to make sure I explained this clearly. I know your daughter helps you manage your health. What will you tell her about the changes we made to your blood pressure medication?”

Teach-back steps:

- I explain the concept to my patients, avoiding medical jargon.

- I assess my patients’ understanding by asking them to explain the concept in their own words.

- I clarify anything my patients did not understand and reassess their understanding.

- If my patients still do not understand, I find a new way to explain the concept.

- I repeat the process of explaining and assessing for understanding until my patients are able to accurately state their understanding.

There are a few key things to remember as you perform teach-back. The first is to ensure you use a caring tone when speaking with your patients. Next, if you have several concepts you want to teach, break it into small pieces. Use teach-back for the first concept before moving on to the next. Finally, one of the most common questions I get from other doctors about teach-back is how to assess patients’ understanding without sounding condescending. I address this by making it about me and my effectiveness as a teacher. I tell my patients it is my responsibility to explain things in a way they understand, so if they do not, I will explain it in a different way. When I frame it this way, patients are not offended by my asking them to perform teach-back because they realize I’m doing it as a test of my effectiveness as a teacher.

Example: “Mr. Johnson, as your doctor, one of my top priorities is to ensure I’m explaining things in a way you understand. I want to make sure my instructions about how to take your new medication are clear. Would you mind telling me in your own words how you will take this new medication?”

Now that you know what teach-back is and understand how helpful it can be, start incorporating it into your practice. Think about a few concepts that you teach again and again, such as disease management, medication changes, and self-care instructions. Next, think about how you could use teach-back in these scenarios. Practice what you will say when you ask patients to engage in teach-back. Finally, commit to using teach-back with your next few patients. The more you practice, the easier it becomes.

For more information on teach-back, visit www.teachbacktraining.org.

Dr. Dorrah is regional medical director for quality and the patient experience, Baylor Scott & White Health, Round Rock, Texas.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I use the teach-back method to confirm my patients’ understanding.

Why I Do It

Teach-back allows me to address my patients’ uncertainty about the plan and clarify any misunderstandings.

As doctors, one of our most important jobs is explaining in ways our patients understand. It doesn’t matter how brilliant our treatment plan is if our patients do not understand it. We all want to feel like we’re making a difference in our patients’ lives. Yet it’s hard for our patients to do what we recommend if they don’t understand.

Unfortunately, many patients are too embarrassed to ask questions, or they simply do not know what to ask. Patients will also say they understand everything even when they do not because they fear appearing uneducated.

This is why the teach-back method is so valuable. The teach-back method allows you to better assess your patients’ understanding of their medical problems. It allows you to uncover and clarify any misunderstandings your patients may have about the plan. It also helps you to engage in a more collaborative relationship with your patients.

How I Do It

Teach-back helps me to test my effectiveness as a teacher by allowing me to assess whether my patient understands; if not, I explain in a different way.

One of the common mistakes clinicians make when assessing for understanding is asking, “Do you have any questions?” or “Does this make sense?” The problem with these questions is that they are closed-ended. The only responses are yes or no. Your patients may say they understand even when they do not. In reality, it does not matter how brilliant your treatment plans are if patients do not follow them because they do not understand.

Teach-back encourages the doctor to check for understanding by using open-ended instead of closed-ended questions.

Example one: “This is a new diagnosis for you, so I want to make sure you understand. Will you tell me in your own words what congestive heart failure is?”

Example two: “I want to make sure I explained this clearly. I know your daughter helps you manage your health. What will you tell her about the changes we made to your blood pressure medication?”

Teach-back steps:

- I explain the concept to my patients, avoiding medical jargon.

- I assess my patients’ understanding by asking them to explain the concept in their own words.

- I clarify anything my patients did not understand and reassess their understanding.

- If my patients still do not understand, I find a new way to explain the concept.

- I repeat the process of explaining and assessing for understanding until my patients are able to accurately state their understanding.

There are a few key things to remember as you perform teach-back. The first is to ensure you use a caring tone when speaking with your patients. Next, if you have several concepts you want to teach, break it into small pieces. Use teach-back for the first concept before moving on to the next. Finally, one of the most common questions I get from other doctors about teach-back is how to assess patients’ understanding without sounding condescending. I address this by making it about me and my effectiveness as a teacher. I tell my patients it is my responsibility to explain things in a way they understand, so if they do not, I will explain it in a different way. When I frame it this way, patients are not offended by my asking them to perform teach-back because they realize I’m doing it as a test of my effectiveness as a teacher.

Example: “Mr. Johnson, as your doctor, one of my top priorities is to ensure I’m explaining things in a way you understand. I want to make sure my instructions about how to take your new medication are clear. Would you mind telling me in your own words how you will take this new medication?”

Now that you know what teach-back is and understand how helpful it can be, start incorporating it into your practice. Think about a few concepts that you teach again and again, such as disease management, medication changes, and self-care instructions. Next, think about how you could use teach-back in these scenarios. Practice what you will say when you ask patients to engage in teach-back. Finally, commit to using teach-back with your next few patients. The more you practice, the easier it becomes.

For more information on teach-back, visit www.teachbacktraining.org.

Dr. Dorrah is regional medical director for quality and the patient experience, Baylor Scott & White Health, Round Rock, Texas.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I use the teach-back method to confirm my patients’ understanding.

Why I Do It

Teach-back allows me to address my patients’ uncertainty about the plan and clarify any misunderstandings.

As doctors, one of our most important jobs is explaining in ways our patients understand. It doesn’t matter how brilliant our treatment plan is if our patients do not understand it. We all want to feel like we’re making a difference in our patients’ lives. Yet it’s hard for our patients to do what we recommend if they don’t understand.

Unfortunately, many patients are too embarrassed to ask questions, or they simply do not know what to ask. Patients will also say they understand everything even when they do not because they fear appearing uneducated.

This is why the teach-back method is so valuable. The teach-back method allows you to better assess your patients’ understanding of their medical problems. It allows you to uncover and clarify any misunderstandings your patients may have about the plan. It also helps you to engage in a more collaborative relationship with your patients.

How I Do It

Teach-back helps me to test my effectiveness as a teacher by allowing me to assess whether my patient understands; if not, I explain in a different way.

One of the common mistakes clinicians make when assessing for understanding is asking, “Do you have any questions?” or “Does this make sense?” The problem with these questions is that they are closed-ended. The only responses are yes or no. Your patients may say they understand even when they do not. In reality, it does not matter how brilliant your treatment plans are if patients do not follow them because they do not understand.

Teach-back encourages the doctor to check for understanding by using open-ended instead of closed-ended questions.

Example one: “This is a new diagnosis for you, so I want to make sure you understand. Will you tell me in your own words what congestive heart failure is?”

Example two: “I want to make sure I explained this clearly. I know your daughter helps you manage your health. What will you tell her about the changes we made to your blood pressure medication?”

Teach-back steps:

- I explain the concept to my patients, avoiding medical jargon.

- I assess my patients’ understanding by asking them to explain the concept in their own words.

- I clarify anything my patients did not understand and reassess their understanding.

- If my patients still do not understand, I find a new way to explain the concept.

- I repeat the process of explaining and assessing for understanding until my patients are able to accurately state their understanding.

There are a few key things to remember as you perform teach-back. The first is to ensure you use a caring tone when speaking with your patients. Next, if you have several concepts you want to teach, break it into small pieces. Use teach-back for the first concept before moving on to the next. Finally, one of the most common questions I get from other doctors about teach-back is how to assess patients’ understanding without sounding condescending. I address this by making it about me and my effectiveness as a teacher. I tell my patients it is my responsibility to explain things in a way they understand, so if they do not, I will explain it in a different way. When I frame it this way, patients are not offended by my asking them to perform teach-back because they realize I’m doing it as a test of my effectiveness as a teacher.

Example: “Mr. Johnson, as your doctor, one of my top priorities is to ensure I’m explaining things in a way you understand. I want to make sure my instructions about how to take your new medication are clear. Would you mind telling me in your own words how you will take this new medication?”

Now that you know what teach-back is and understand how helpful it can be, start incorporating it into your practice. Think about a few concepts that you teach again and again, such as disease management, medication changes, and self-care instructions. Next, think about how you could use teach-back in these scenarios. Practice what you will say when you ask patients to engage in teach-back. Finally, commit to using teach-back with your next few patients. The more you practice, the easier it becomes.

For more information on teach-back, visit www.teachbacktraining.org.

Dr. Dorrah is regional medical director for quality and the patient experience, Baylor Scott & White Health, Round Rock, Texas.

Clarifying the Roles of Hospitalist and PCP

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I explain my role as a hospitalist and my connection to the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) on first meeting the patient. I look for ways to reinforce this throughout the hospitalization.

Why I Do It

Even when I was hospitalized at my own institution, it was difficult for me to remember all of the providers involved in my care and their roles. My injuries and the large number of doctors caring for me interfered with my ability to absorb this information. I imagine that this is amplified for patients who have little or no experience with the medical system and are unfamiliar with the role that we play in their care.

During a recent initiative to improve the patient experience at my institution, we found it difficult to collect specific feedback on individual providers because many patients did not know their inpatient doctors’ names, frequently referencing their PCPs when asked for feedback on their care. This is common: A 2009 study showed that 75% of patients were unable to name the inpatient physician in charge of their care. Of those who could identify a name, only 40% correctly identified a member of their primary inpatient team, often identifying the PCP or a specialist instead.1

Clarifying our role on the care team, identifying ourselves as the point person for questions or concerns, and reinforcing our relationship with the PCP can help engender trust in the relationship, eliminate confusion, and improve the patient experience.

How I Do It

After introducing myself, I explain to patients that I will notify their PCP of the admission, and I state that I will be acting as the head of the inpatient team on behalf of their PCP. I often explain that most PCPs do not see their own patients in the hospital.

When multiple teams or house staff are involved in care, I clarify my role in relation to other team members. I look for opportunities throughout the hospitalization to reinforce this. For example, I tell patients when I have updated their PCP on significant events, and I clarify my role in simple terms, such as “quarterback,” when there are multiple subspecialists involved in care. I try to avoid terms like “attending,” which are often meaningless to patients.

In my hospitalist group, we help to reinforce our role and identity by providing a business card that includes a headshot. TH

Dr. Moore is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She is a member of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Reference

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I explain my role as a hospitalist and my connection to the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) on first meeting the patient. I look for ways to reinforce this throughout the hospitalization.

Why I Do It

Even when I was hospitalized at my own institution, it was difficult for me to remember all of the providers involved in my care and their roles. My injuries and the large number of doctors caring for me interfered with my ability to absorb this information. I imagine that this is amplified for patients who have little or no experience with the medical system and are unfamiliar with the role that we play in their care.

During a recent initiative to improve the patient experience at my institution, we found it difficult to collect specific feedback on individual providers because many patients did not know their inpatient doctors’ names, frequently referencing their PCPs when asked for feedback on their care. This is common: A 2009 study showed that 75% of patients were unable to name the inpatient physician in charge of their care. Of those who could identify a name, only 40% correctly identified a member of their primary inpatient team, often identifying the PCP or a specialist instead.1

Clarifying our role on the care team, identifying ourselves as the point person for questions or concerns, and reinforcing our relationship with the PCP can help engender trust in the relationship, eliminate confusion, and improve the patient experience.

How I Do It

After introducing myself, I explain to patients that I will notify their PCP of the admission, and I state that I will be acting as the head of the inpatient team on behalf of their PCP. I often explain that most PCPs do not see their own patients in the hospital.

When multiple teams or house staff are involved in care, I clarify my role in relation to other team members. I look for opportunities throughout the hospitalization to reinforce this. For example, I tell patients when I have updated their PCP on significant events, and I clarify my role in simple terms, such as “quarterback,” when there are multiple subspecialists involved in care. I try to avoid terms like “attending,” which are often meaningless to patients.

In my hospitalist group, we help to reinforce our role and identity by providing a business card that includes a headshot. TH

Dr. Moore is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She is a member of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Reference

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each article will focus on how the contributor applies one or more of the “key communication” tactics in practice to maintain provider accountability for “everything we say and do that affects our patients’ thoughts, feelings, and well-being.”

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I explain my role as a hospitalist and my connection to the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) on first meeting the patient. I look for ways to reinforce this throughout the hospitalization.

Why I Do It

Even when I was hospitalized at my own institution, it was difficult for me to remember all of the providers involved in my care and their roles. My injuries and the large number of doctors caring for me interfered with my ability to absorb this information. I imagine that this is amplified for patients who have little or no experience with the medical system and are unfamiliar with the role that we play in their care.

During a recent initiative to improve the patient experience at my institution, we found it difficult to collect specific feedback on individual providers because many patients did not know their inpatient doctors’ names, frequently referencing their PCPs when asked for feedback on their care. This is common: A 2009 study showed that 75% of patients were unable to name the inpatient physician in charge of their care. Of those who could identify a name, only 40% correctly identified a member of their primary inpatient team, often identifying the PCP or a specialist instead.1

Clarifying our role on the care team, identifying ourselves as the point person for questions or concerns, and reinforcing our relationship with the PCP can help engender trust in the relationship, eliminate confusion, and improve the patient experience.

How I Do It

After introducing myself, I explain to patients that I will notify their PCP of the admission, and I state that I will be acting as the head of the inpatient team on behalf of their PCP. I often explain that most PCPs do not see their own patients in the hospital.

When multiple teams or house staff are involved in care, I clarify my role in relation to other team members. I look for opportunities throughout the hospitalization to reinforce this. For example, I tell patients when I have updated their PCP on significant events, and I clarify my role in simple terms, such as “quarterback,” when there are multiple subspecialists involved in care. I try to avoid terms like “attending,” which are often meaningless to patients.

In my hospitalist group, we help to reinforce our role and identity by providing a business card that includes a headshot. TH

Dr. Moore is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and an instructor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. She is a member of SHM’s Patient Experience Committee.

Reference

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

Engaging Your Patients in Decision-Making Processes Yields Better Outcomes

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I counsel and deliver the diagnosis or give recommendations through a dialogue, instead of a monologue, using active listening.

Why I Do It

The monologue, or lecture, is among the least effective ways to instill behavior change. Research studies have demonstrated that, after a monologue, only around 20% to 60% of medical information is remembered by the end of a visit. Out of what is remembered, less than 50% is accurate. Furthermore, 47% of Americans have health literacy levels below the intermediate range, defined as the ability to determine when to take a medication with food from reading the label.

Lecturing the patient without first understanding what the patient knows and finds important, and understanding the barriers to plan implementation, runs the risk of decreased comprehension, a lack of understanding, or a lack of personal relevance—all leading to decreased adherence. Doing the opposite, by involving the patient in decision making, inspires change that comes from within in the context of the patient’s own needs. This approach is more enduring, emphasizes self-accountability, and ultimately leads to better outcomes.

How I Do It

I open up a dialogue using the Cleveland Clinic’s ARIA approach as adapted from the REDE model of healthcare communication.1

- First, assess: What does the patient know about diagnosis and treatment? How much and what type of education does the patient desire/need? What are the patient’s treatment preferences and health literacy?

- Second, reflect on what the patient just said. Validate meaning and emotion.

- Third, inform the patient within the context of the patient’s perspectives and preferences. Speak slowly and provide small chunks of information at a time. Use understandable language and visual aids. (This will increase recall by 60%.)

- Finally, assess the patient’s understanding and emotional reaction to information provided.

- Repeat the cycle to introduce other chunks of information.

Dr. Velez is director of faculty development in the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication at the Cleveland Clinic.

Reference

- Windover A, Boissy A, Rice T, Gilligan T, Velez V, Merlino J. The REDE model of healthcare communication: optimizing relationship as a therapeutic agent. J Patient Exp. 2014;1(1):8-13.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I counsel and deliver the diagnosis or give recommendations through a dialogue, instead of a monologue, using active listening.

Why I Do It

The monologue, or lecture, is among the least effective ways to instill behavior change. Research studies have demonstrated that, after a monologue, only around 20% to 60% of medical information is remembered by the end of a visit. Out of what is remembered, less than 50% is accurate. Furthermore, 47% of Americans have health literacy levels below the intermediate range, defined as the ability to determine when to take a medication with food from reading the label.

Lecturing the patient without first understanding what the patient knows and finds important, and understanding the barriers to plan implementation, runs the risk of decreased comprehension, a lack of understanding, or a lack of personal relevance—all leading to decreased adherence. Doing the opposite, by involving the patient in decision making, inspires change that comes from within in the context of the patient’s own needs. This approach is more enduring, emphasizes self-accountability, and ultimately leads to better outcomes.

How I Do It

I open up a dialogue using the Cleveland Clinic’s ARIA approach as adapted from the REDE model of healthcare communication.1

- First, assess: What does the patient know about diagnosis and treatment? How much and what type of education does the patient desire/need? What are the patient’s treatment preferences and health literacy?

- Second, reflect on what the patient just said. Validate meaning and emotion.

- Third, inform the patient within the context of the patient’s perspectives and preferences. Speak slowly and provide small chunks of information at a time. Use understandable language and visual aids. (This will increase recall by 60%.)

- Finally, assess the patient’s understanding and emotional reaction to information provided.

- Repeat the cycle to introduce other chunks of information.

Dr. Velez is director of faculty development in the Center for Excellence in Healthcare Communication at the Cleveland Clinic.

Reference

- Windover A, Boissy A, Rice T, Gilligan T, Velez V, Merlino J. The REDE model of healthcare communication: optimizing relationship as a therapeutic agent. J Patient Exp. 2014;1(1):8-13.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by SHM’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care. Each column will focus on how the contributor applies one of the “Key Communication” areas in practice.

View a chart outlining key communication tactics

What I Say and Do

I counsel and deliver the diagnosis or give recommendations through a dialogue, instead of a monologue, using active listening.

Why I Do It