User login

Banner Good Samaritan Battles VTE in Real Time

Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix is combating hospital-acquired VTE with a quality initiative that uses risk-assessment tools and order sets embedded in the electronic health record (EHR) and real-time interventions with physicians.

Cases of hospital-acquired VTE are identified as they occur and assessed for whether they were preventable, says Lori Porter, DO, academic hospitalist and team leader for Banner Good Samaritan's VTE Committee. "If we think the VTE was preventable, we will call the provider and say, 'Can you tell me why you think this happened?'" she says. (Check out more information about Banner Good Samaritan’s VTE program at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement website.)

The program emphasizes risk re-assessment, appropriate use of extended prophylaxis, and involvement of Banner's house staff. All four hospitalist services at Banner Good Samaritan have been receptive to using the order sets.

Banner Good Samaritan's results include a drop in preventable hospital-acquired VTEs to 25% in 2011 from 45% in 2009, along with a 29% relative risk reduction in DVT and 18% in pulmonary embolism.

The hospital belongs to SHM's VTE Prevention Collaborative, and works with mentor Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM's Center for Healthcare Improvement and Innovation. It uses what Dr. Porter calls "a simple, three-bucket system" for assessing and classifying risk level, derived from the 2008 antithrombotic therapy guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). However, in February, ACCP issued a new edition of the guidelines, which Dr. Porter has not been eager to embrace.

"They've gone back to a conservative point-scoring system for risk assessment, which seems cumbersome in clinical practice. If a simpler approach has proven to be effective for us, then why commit to making a complicated change?" says Dr. Porter.

Dr. Maynard agrees that the new antithrombotic guidelines have sparked differences of opinion. Dr. Porter's teams, for example, "use the simpler three-bucket model with good results: better prophylaxis, decrease in VTE, and no discernible increase in bleeding," he says. "Improvement teams that want to mimic these results should look at this model, in addition to the models outlined in the ninth edition, and see which models their doctors and nurses would actually use reliably."

Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix is combating hospital-acquired VTE with a quality initiative that uses risk-assessment tools and order sets embedded in the electronic health record (EHR) and real-time interventions with physicians.

Cases of hospital-acquired VTE are identified as they occur and assessed for whether they were preventable, says Lori Porter, DO, academic hospitalist and team leader for Banner Good Samaritan's VTE Committee. "If we think the VTE was preventable, we will call the provider and say, 'Can you tell me why you think this happened?'" she says. (Check out more information about Banner Good Samaritan’s VTE program at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement website.)

The program emphasizes risk re-assessment, appropriate use of extended prophylaxis, and involvement of Banner's house staff. All four hospitalist services at Banner Good Samaritan have been receptive to using the order sets.

Banner Good Samaritan's results include a drop in preventable hospital-acquired VTEs to 25% in 2011 from 45% in 2009, along with a 29% relative risk reduction in DVT and 18% in pulmonary embolism.

The hospital belongs to SHM's VTE Prevention Collaborative, and works with mentor Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM's Center for Healthcare Improvement and Innovation. It uses what Dr. Porter calls "a simple, three-bucket system" for assessing and classifying risk level, derived from the 2008 antithrombotic therapy guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). However, in February, ACCP issued a new edition of the guidelines, which Dr. Porter has not been eager to embrace.

"They've gone back to a conservative point-scoring system for risk assessment, which seems cumbersome in clinical practice. If a simpler approach has proven to be effective for us, then why commit to making a complicated change?" says Dr. Porter.

Dr. Maynard agrees that the new antithrombotic guidelines have sparked differences of opinion. Dr. Porter's teams, for example, "use the simpler three-bucket model with good results: better prophylaxis, decrease in VTE, and no discernible increase in bleeding," he says. "Improvement teams that want to mimic these results should look at this model, in addition to the models outlined in the ninth edition, and see which models their doctors and nurses would actually use reliably."

Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center in Phoenix is combating hospital-acquired VTE with a quality initiative that uses risk-assessment tools and order sets embedded in the electronic health record (EHR) and real-time interventions with physicians.

Cases of hospital-acquired VTE are identified as they occur and assessed for whether they were preventable, says Lori Porter, DO, academic hospitalist and team leader for Banner Good Samaritan's VTE Committee. "If we think the VTE was preventable, we will call the provider and say, 'Can you tell me why you think this happened?'" she says. (Check out more information about Banner Good Samaritan’s VTE program at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement website.)

The program emphasizes risk re-assessment, appropriate use of extended prophylaxis, and involvement of Banner's house staff. All four hospitalist services at Banner Good Samaritan have been receptive to using the order sets.

Banner Good Samaritan's results include a drop in preventable hospital-acquired VTEs to 25% in 2011 from 45% in 2009, along with a 29% relative risk reduction in DVT and 18% in pulmonary embolism.

The hospital belongs to SHM's VTE Prevention Collaborative, and works with mentor Gregory Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM's Center for Healthcare Improvement and Innovation. It uses what Dr. Porter calls "a simple, three-bucket system" for assessing and classifying risk level, derived from the 2008 antithrombotic therapy guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). However, in February, ACCP issued a new edition of the guidelines, which Dr. Porter has not been eager to embrace.

"They've gone back to a conservative point-scoring system for risk assessment, which seems cumbersome in clinical practice. If a simpler approach has proven to be effective for us, then why commit to making a complicated change?" says Dr. Porter.

Dr. Maynard agrees that the new antithrombotic guidelines have sparked differences of opinion. Dr. Porter's teams, for example, "use the simpler three-bucket model with good results: better prophylaxis, decrease in VTE, and no discernible increase in bleeding," he says. "Improvement teams that want to mimic these results should look at this model, in addition to the models outlined in the ninth edition, and see which models their doctors and nurses would actually use reliably."

Training, Leadership, Commitment Integral to HM Improving Stroke Care

Stroke specialists like to say that “time is brain.” With an emphatic focus on those first few critical hours, however, it’s sometimes easy to overlook the vital role that hospitalists play in the days, weeks, and months that follow.

A recent study in The Neurohospitalist suggests that compared to community-based neurologists, practitioners of neurohospital medicine can reduce the length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke.1 A separate study, however, suggests that similar success might have come at a price for their less-specialized hospitalist counterparts.2 Among stroke patients, the latter study found that while the HM model is also associated with a reduced length of stay, it is associated with increased discharges to inpatient rehabilitation centers instead of to home, and higher readmission rates.

In sum, the evidence raises questions about whether rank-and-file hospitalists are adequately equipped to deal with a disease that is a core competency for the profession and ranks among the top sources of adult disability in the United States, at an estimated cost of $34.3 billion in 2008.3

“I think there’s been a mismatch between the training of the average hospitalist and then the expectations for the amount of neurological care they end up delivering once in practice,” says David Likosky, MD, SFHM, director of the stroke program at Evergreen Hospital Medical Center in Kirkland, Wash. “When surveyed, it’s been shown that hospitalists feel that care of stroke is one of the areas with which they’re least comfortable once they get out into practice.” Over the past decade, several studies have reinforced the notion of a training deficit.4,5

Demographic trends suggest that getting up to speed will be imperative, however. “One alarming thing we’re seeing is strokes among individuals that are not in the elderly group, and that group seems to be increasing at an alarming rate,” says Daniel T. Lackland, PhD, professor of epidemiology and neurosciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Hospitals are seeing more ischemic stroke patients in their 40s and 50s, likely a reflection of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia that are occurring earlier in life. And because those patients are younger, the aftermath of a stroke could linger for decades.

Although the stroke mortality rate is declining in the U.S., statistics find that about 14% of all patients diagnosed with an initial stroke will have a second one within a year, placing continued strain on a healthcare system already stretched thin.6 Hospitalists, Dr. Lackland says, have an “ideal” opportunity to help build up and improve that system, potentially yielding significant cost savings along with the dramatic improvement in quality of life. Making the most of that opportunity, though, will require a solid understanding of multiple trends that are quickly transforming stroke care delivery.

Time Is of the Essence

Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says hospitals are focusing more and more on a metric known as “door-to-needle time.” The goal is to treat at least half of incoming ischemic stroke patients with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV tPA) within the first 60 minutes after onset of symptoms.

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has reinforced the message with its Get With the Guidelines Stroke Program. A recent analysis suggested the program has led to more timely tPA administration and, in turn, better patient outcomes (the program is funded in part through the Bristol-Myers Squib/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership).7

At the same time, clinical research has widened the window for IV tPA delivery from three hours to 4.5 hours for certain patients after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Barrett says “strong evidence” from the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III has convinced most clinicians, and the FDA is expected to follow suit in officially approving the extension.8 As more stroke centers become certified, the use of IV tPA has increased accordingly.

Patients who have missed the time window or are not good candidates for IV tPA can still be aided by interarterial tPA at the site of the clot up to six hours after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Likosky says the treatment option should be of particular interest to hospitalists, given that strokes can occur post-operatively and in other patients who cannot receive IV tPA because of bleeding risk.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, Eagle Hospital Physicians, Roswell, Ga.

For up to eight hours after the onset of symptoms, mechanical clot removal techniques have shown continued efficacy at revascularizing affected areas, with some newer options also offering greater promise of improving patient outcomes. Even with the prospects of declining complication rates, however, “evaluating and initiating treatment in a timely fashion is still going to be one of the most important predictors of outcome,” Dr. Barrett says.

After the initial intervention, hospitalists often are the go-to providers for anticipating and preventing common post-stroke complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, VTE from immobilization, and other infections. The proper use of anti-platelet agents and high-dose statins, also falling solidly within the HM realm, can pay big dividends if used consistently.

Meanwhile, newer studies and clinical observations are widening the scope of considerations that should be on every hospitalist’s radar. Here are a few cited by stroke experts:

Permissive hypertension. After an ischemic stroke, the benefit of permissive hypertension is still widely misunderstood. Perhaps counterintuitively, high blood pressure after a stroke can help protect the area of the brain that is damaged but not yet dead, sometimes called the penumbra. “I highlight this because I think it’s a common mistake, that internists are very used to high blood pressure being a bad thing,” says Andrew Josephson, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology and director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center. “And in general, it is; it’s a cause of stroke. But once somebody has a stroke, in the acute period, it’s important to allow the blood pressure to be high.”

Atrial fibrillation. The accepted role of atrial fibrillation in stroke is evolving. Research suggests that the common but often preventable arrhythmia is an important cause of stroke in about 15% to 20% of cases.9 By the time of hospital discharge, however, Dr. Josephson says physicians haven’t established a cause in about 1 in 4 cases. For these “cryptogenic strokes,” he says, doctors have long suspected that atrial fibrillation not picked up during the initial EKG or by the monitoring with cardiac telemetry could be a major cause.

Recent observations suggest that a longer monitoring period of up to 30 days may uncover atrial fibrillation in a sizable fraction of those patients, highlighting the importance of keeping a close eye on stroke patients both in the hospital and beyond. “It’s very important to identify, because atrial fibrillation changes what we do for folks to prevent a second stroke,” Dr. Josephson explains. Instead of anti-platelet medicine like aspirin, patients with atrial fibrillation often receive anticoagulants like warfarin, or the more recently approved dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Transient ischemic attack. Improvements in imaging techniques like MRI have likewise begun to shift how stroke patients are treated. For example, Dr. Likosky says, medicine is moving away from a time-based definition of transient ischemic attack (TIA), in which symptoms resolve within 24 hours, to a tissue-based definition. Recent MRI imaging has uncovered evidence of a new infarction in more than half of patients initially diagnosed with TIA.10

“If they do have an infarction on their scan, even if they had symptoms that only lasted for five minutes, that’s a stroke,” Dr. Josephson says. And even a true TIA, he says, represents “a kind of stroke where you got really lucky and you’re not left with deficits, but the risk is still very high.” Accordingly, more patients with TIA are being admitted to the hospital to receive a full workup and preventive treatment. “We think that by evaluating these people urgently, we can reduce the risk of having a stroke by maybe 75% over a three-month time period,” Dr. Josephson says.

Hemorrhagic stroke. To date, the vast majority of patients with hemorrhagic stroke (which accounts for only 13% of all stroke cases) have been managed by neurosurgeons and neurologists. But here, too, Dr. Likosky says the picture could be changing. Recent findings that surgical treatment of intracranial hemorrhaging might not benefit many patients could shift the care paradigm toward a medical management strategy that involves more hospitalists.

Innovations Aplenty

The increasing complexity of stroke care and uneven distribution of resources and expertise have helped fuel several important innovations in delivery, most notably telestroke and neurohospital medicine. Both are being driven, in part, by an increased awareness of time-sensitive interventions and a frequent lack of on-site neurologists at smaller and more rural facilities. If telestroke programs are expanding the reach of neurologists, neurohospitalists are helping to fill the gaps in inpatient stroke care.

Amid the changes, one element is proving a necessary constant: a team approach that relies heavily on the HM emphasis on quality metrics, intensive monitoring, and careful coordination. Who better to lead the charge than hospitalists, says Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “They’re the ones who are in the hospital, and when these patients go bad, they go bad fast,” she says.

More broadly, Dr. Jensen says, hospitalists should get in on the ground floor when their facility seeks certification as a primary or a comprehensive stroke center. “And they need to make sure that the hospital isn’t just trying to get the sexy elements—the guy with the cath or the gal with the cath who can pull the clot out—but that they have a complete program that involves the care of the patient after they’ve had the procedure done,” she says.

As healthcare reform efforts are making clear, the responsibility doesn’t end after discharge, either. The Affordable Care Act includes a hospital readmission reduction program that will kick in this October, with penalties for hospitals posting unacceptably high 30-day readmission rates. Amy Kind, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, is convinced that a key contributor to high rehospitalization rates among stroke patients may be the woefully incomplete nature of discharge communication.

—Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Dr. Kind, for example, has found a disturbing pattern in communication regarding issues like dysphagia, a common complication among stroke patients and an important risk factor for pneumonia. Countering the risk usually requires such measures as putting patients on a special diet or elevating the head of their bed. “We looked at the quality of the communication of that information in discharge summaries, and it’s just abysmal. It’s absolutely abysmal,” she says. Without clear directives to providers in the next setting of care, such as a skilled-nursing facility, patients could be erroneously put back on a regular diet and aspirate, sending them right back to the hospital.

As one potential solution, Dr. Kind’s team is developing a multidisciplinary stroke discharge summary tool that automatically imports elements like speech-language pathology and dietary recommendations. Although most discharge communication may focus on more visible issues and interventions, Dr. Kind argues that some of the “bread and butter” concerns might ultimately prove just as important for long-term patient outcomes.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, vice president of clinical systems integration and medical director of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, sees telemedicine as another potential tool to help reach patients after discharge, especially those who haven’t received follow-up care from a primary-care physician (PCP). “We need to be the champions at our hospitals for improving care processes, and we need to work in partnership with the nurses and the other professionals,” Dr. Godamunne says. “As a group, we can really make a difference, and stroke is one of those areas in which we can truly contribute.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Freeman WD, Dawson SB, Raper C, Thiemann K, et al. Neurohospitalists reduce length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke. The Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(2): 67-70.

- Howrey BT, Kuo Y-F, Goodwin JS. Association of care by hospitalists on discharge destination and 30-day outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Medical Care. 2011;49(8): 701-707.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 111(3):247-254.

- Dickerson LM, Carek PJ, Quattlebaum RG. Prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76(3):382-388.

- Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123(7):750-758.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, et al. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e91.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack—proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003.

Stroke specialists like to say that “time is brain.” With an emphatic focus on those first few critical hours, however, it’s sometimes easy to overlook the vital role that hospitalists play in the days, weeks, and months that follow.

A recent study in The Neurohospitalist suggests that compared to community-based neurologists, practitioners of neurohospital medicine can reduce the length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke.1 A separate study, however, suggests that similar success might have come at a price for their less-specialized hospitalist counterparts.2 Among stroke patients, the latter study found that while the HM model is also associated with a reduced length of stay, it is associated with increased discharges to inpatient rehabilitation centers instead of to home, and higher readmission rates.

In sum, the evidence raises questions about whether rank-and-file hospitalists are adequately equipped to deal with a disease that is a core competency for the profession and ranks among the top sources of adult disability in the United States, at an estimated cost of $34.3 billion in 2008.3

“I think there’s been a mismatch between the training of the average hospitalist and then the expectations for the amount of neurological care they end up delivering once in practice,” says David Likosky, MD, SFHM, director of the stroke program at Evergreen Hospital Medical Center in Kirkland, Wash. “When surveyed, it’s been shown that hospitalists feel that care of stroke is one of the areas with which they’re least comfortable once they get out into practice.” Over the past decade, several studies have reinforced the notion of a training deficit.4,5

Demographic trends suggest that getting up to speed will be imperative, however. “One alarming thing we’re seeing is strokes among individuals that are not in the elderly group, and that group seems to be increasing at an alarming rate,” says Daniel T. Lackland, PhD, professor of epidemiology and neurosciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Hospitals are seeing more ischemic stroke patients in their 40s and 50s, likely a reflection of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia that are occurring earlier in life. And because those patients are younger, the aftermath of a stroke could linger for decades.

Although the stroke mortality rate is declining in the U.S., statistics find that about 14% of all patients diagnosed with an initial stroke will have a second one within a year, placing continued strain on a healthcare system already stretched thin.6 Hospitalists, Dr. Lackland says, have an “ideal” opportunity to help build up and improve that system, potentially yielding significant cost savings along with the dramatic improvement in quality of life. Making the most of that opportunity, though, will require a solid understanding of multiple trends that are quickly transforming stroke care delivery.

Time Is of the Essence

Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says hospitals are focusing more and more on a metric known as “door-to-needle time.” The goal is to treat at least half of incoming ischemic stroke patients with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV tPA) within the first 60 minutes after onset of symptoms.

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has reinforced the message with its Get With the Guidelines Stroke Program. A recent analysis suggested the program has led to more timely tPA administration and, in turn, better patient outcomes (the program is funded in part through the Bristol-Myers Squib/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership).7

At the same time, clinical research has widened the window for IV tPA delivery from three hours to 4.5 hours for certain patients after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Barrett says “strong evidence” from the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III has convinced most clinicians, and the FDA is expected to follow suit in officially approving the extension.8 As more stroke centers become certified, the use of IV tPA has increased accordingly.

Patients who have missed the time window or are not good candidates for IV tPA can still be aided by interarterial tPA at the site of the clot up to six hours after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Likosky says the treatment option should be of particular interest to hospitalists, given that strokes can occur post-operatively and in other patients who cannot receive IV tPA because of bleeding risk.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, Eagle Hospital Physicians, Roswell, Ga.

For up to eight hours after the onset of symptoms, mechanical clot removal techniques have shown continued efficacy at revascularizing affected areas, with some newer options also offering greater promise of improving patient outcomes. Even with the prospects of declining complication rates, however, “evaluating and initiating treatment in a timely fashion is still going to be one of the most important predictors of outcome,” Dr. Barrett says.

After the initial intervention, hospitalists often are the go-to providers for anticipating and preventing common post-stroke complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, VTE from immobilization, and other infections. The proper use of anti-platelet agents and high-dose statins, also falling solidly within the HM realm, can pay big dividends if used consistently.

Meanwhile, newer studies and clinical observations are widening the scope of considerations that should be on every hospitalist’s radar. Here are a few cited by stroke experts:

Permissive hypertension. After an ischemic stroke, the benefit of permissive hypertension is still widely misunderstood. Perhaps counterintuitively, high blood pressure after a stroke can help protect the area of the brain that is damaged but not yet dead, sometimes called the penumbra. “I highlight this because I think it’s a common mistake, that internists are very used to high blood pressure being a bad thing,” says Andrew Josephson, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology and director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center. “And in general, it is; it’s a cause of stroke. But once somebody has a stroke, in the acute period, it’s important to allow the blood pressure to be high.”

Atrial fibrillation. The accepted role of atrial fibrillation in stroke is evolving. Research suggests that the common but often preventable arrhythmia is an important cause of stroke in about 15% to 20% of cases.9 By the time of hospital discharge, however, Dr. Josephson says physicians haven’t established a cause in about 1 in 4 cases. For these “cryptogenic strokes,” he says, doctors have long suspected that atrial fibrillation not picked up during the initial EKG or by the monitoring with cardiac telemetry could be a major cause.

Recent observations suggest that a longer monitoring period of up to 30 days may uncover atrial fibrillation in a sizable fraction of those patients, highlighting the importance of keeping a close eye on stroke patients both in the hospital and beyond. “It’s very important to identify, because atrial fibrillation changes what we do for folks to prevent a second stroke,” Dr. Josephson explains. Instead of anti-platelet medicine like aspirin, patients with atrial fibrillation often receive anticoagulants like warfarin, or the more recently approved dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Transient ischemic attack. Improvements in imaging techniques like MRI have likewise begun to shift how stroke patients are treated. For example, Dr. Likosky says, medicine is moving away from a time-based definition of transient ischemic attack (TIA), in which symptoms resolve within 24 hours, to a tissue-based definition. Recent MRI imaging has uncovered evidence of a new infarction in more than half of patients initially diagnosed with TIA.10

“If they do have an infarction on their scan, even if they had symptoms that only lasted for five minutes, that’s a stroke,” Dr. Josephson says. And even a true TIA, he says, represents “a kind of stroke where you got really lucky and you’re not left with deficits, but the risk is still very high.” Accordingly, more patients with TIA are being admitted to the hospital to receive a full workup and preventive treatment. “We think that by evaluating these people urgently, we can reduce the risk of having a stroke by maybe 75% over a three-month time period,” Dr. Josephson says.

Hemorrhagic stroke. To date, the vast majority of patients with hemorrhagic stroke (which accounts for only 13% of all stroke cases) have been managed by neurosurgeons and neurologists. But here, too, Dr. Likosky says the picture could be changing. Recent findings that surgical treatment of intracranial hemorrhaging might not benefit many patients could shift the care paradigm toward a medical management strategy that involves more hospitalists.

Innovations Aplenty

The increasing complexity of stroke care and uneven distribution of resources and expertise have helped fuel several important innovations in delivery, most notably telestroke and neurohospital medicine. Both are being driven, in part, by an increased awareness of time-sensitive interventions and a frequent lack of on-site neurologists at smaller and more rural facilities. If telestroke programs are expanding the reach of neurologists, neurohospitalists are helping to fill the gaps in inpatient stroke care.

Amid the changes, one element is proving a necessary constant: a team approach that relies heavily on the HM emphasis on quality metrics, intensive monitoring, and careful coordination. Who better to lead the charge than hospitalists, says Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “They’re the ones who are in the hospital, and when these patients go bad, they go bad fast,” she says.

More broadly, Dr. Jensen says, hospitalists should get in on the ground floor when their facility seeks certification as a primary or a comprehensive stroke center. “And they need to make sure that the hospital isn’t just trying to get the sexy elements—the guy with the cath or the gal with the cath who can pull the clot out—but that they have a complete program that involves the care of the patient after they’ve had the procedure done,” she says.

As healthcare reform efforts are making clear, the responsibility doesn’t end after discharge, either. The Affordable Care Act includes a hospital readmission reduction program that will kick in this October, with penalties for hospitals posting unacceptably high 30-day readmission rates. Amy Kind, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, is convinced that a key contributor to high rehospitalization rates among stroke patients may be the woefully incomplete nature of discharge communication.

—Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Dr. Kind, for example, has found a disturbing pattern in communication regarding issues like dysphagia, a common complication among stroke patients and an important risk factor for pneumonia. Countering the risk usually requires such measures as putting patients on a special diet or elevating the head of their bed. “We looked at the quality of the communication of that information in discharge summaries, and it’s just abysmal. It’s absolutely abysmal,” she says. Without clear directives to providers in the next setting of care, such as a skilled-nursing facility, patients could be erroneously put back on a regular diet and aspirate, sending them right back to the hospital.

As one potential solution, Dr. Kind’s team is developing a multidisciplinary stroke discharge summary tool that automatically imports elements like speech-language pathology and dietary recommendations. Although most discharge communication may focus on more visible issues and interventions, Dr. Kind argues that some of the “bread and butter” concerns might ultimately prove just as important for long-term patient outcomes.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, vice president of clinical systems integration and medical director of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, sees telemedicine as another potential tool to help reach patients after discharge, especially those who haven’t received follow-up care from a primary-care physician (PCP). “We need to be the champions at our hospitals for improving care processes, and we need to work in partnership with the nurses and the other professionals,” Dr. Godamunne says. “As a group, we can really make a difference, and stroke is one of those areas in which we can truly contribute.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Freeman WD, Dawson SB, Raper C, Thiemann K, et al. Neurohospitalists reduce length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke. The Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(2): 67-70.

- Howrey BT, Kuo Y-F, Goodwin JS. Association of care by hospitalists on discharge destination and 30-day outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Medical Care. 2011;49(8): 701-707.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 111(3):247-254.

- Dickerson LM, Carek PJ, Quattlebaum RG. Prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76(3):382-388.

- Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123(7):750-758.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, et al. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e91.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack—proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003.

Stroke specialists like to say that “time is brain.” With an emphatic focus on those first few critical hours, however, it’s sometimes easy to overlook the vital role that hospitalists play in the days, weeks, and months that follow.

A recent study in The Neurohospitalist suggests that compared to community-based neurologists, practitioners of neurohospital medicine can reduce the length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke.1 A separate study, however, suggests that similar success might have come at a price for their less-specialized hospitalist counterparts.2 Among stroke patients, the latter study found that while the HM model is also associated with a reduced length of stay, it is associated with increased discharges to inpatient rehabilitation centers instead of to home, and higher readmission rates.

In sum, the evidence raises questions about whether rank-and-file hospitalists are adequately equipped to deal with a disease that is a core competency for the profession and ranks among the top sources of adult disability in the United States, at an estimated cost of $34.3 billion in 2008.3

“I think there’s been a mismatch between the training of the average hospitalist and then the expectations for the amount of neurological care they end up delivering once in practice,” says David Likosky, MD, SFHM, director of the stroke program at Evergreen Hospital Medical Center in Kirkland, Wash. “When surveyed, it’s been shown that hospitalists feel that care of stroke is one of the areas with which they’re least comfortable once they get out into practice.” Over the past decade, several studies have reinforced the notion of a training deficit.4,5

Demographic trends suggest that getting up to speed will be imperative, however. “One alarming thing we’re seeing is strokes among individuals that are not in the elderly group, and that group seems to be increasing at an alarming rate,” says Daniel T. Lackland, PhD, professor of epidemiology and neurosciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Hospitals are seeing more ischemic stroke patients in their 40s and 50s, likely a reflection of risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia that are occurring earlier in life. And because those patients are younger, the aftermath of a stroke could linger for decades.

Although the stroke mortality rate is declining in the U.S., statistics find that about 14% of all patients diagnosed with an initial stroke will have a second one within a year, placing continued strain on a healthcare system already stretched thin.6 Hospitalists, Dr. Lackland says, have an “ideal” opportunity to help build up and improve that system, potentially yielding significant cost savings along with the dramatic improvement in quality of life. Making the most of that opportunity, though, will require a solid understanding of multiple trends that are quickly transforming stroke care delivery.

Time Is of the Essence

Kevin Barrett, MD, MSc, assistant professor of neurology and stroke telemedicine director at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla., says hospitals are focusing more and more on a metric known as “door-to-needle time.” The goal is to treat at least half of incoming ischemic stroke patients with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV tPA) within the first 60 minutes after onset of symptoms.

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association has reinforced the message with its Get With the Guidelines Stroke Program. A recent analysis suggested the program has led to more timely tPA administration and, in turn, better patient outcomes (the program is funded in part through the Bristol-Myers Squib/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership).7

At the same time, clinical research has widened the window for IV tPA delivery from three hours to 4.5 hours for certain patients after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Barrett says “strong evidence” from the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III has convinced most clinicians, and the FDA is expected to follow suit in officially approving the extension.8 As more stroke centers become certified, the use of IV tPA has increased accordingly.

Patients who have missed the time window or are not good candidates for IV tPA can still be aided by interarterial tPA at the site of the clot up to six hours after the onset of symptoms. Dr. Likosky says the treatment option should be of particular interest to hospitalists, given that strokes can occur post-operatively and in other patients who cannot receive IV tPA because of bleeding risk.

—Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, medical director, Eagle Hospital Physicians, Roswell, Ga.

For up to eight hours after the onset of symptoms, mechanical clot removal techniques have shown continued efficacy at revascularizing affected areas, with some newer options also offering greater promise of improving patient outcomes. Even with the prospects of declining complication rates, however, “evaluating and initiating treatment in a timely fashion is still going to be one of the most important predictors of outcome,” Dr. Barrett says.

After the initial intervention, hospitalists often are the go-to providers for anticipating and preventing common post-stroke complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, VTE from immobilization, and other infections. The proper use of anti-platelet agents and high-dose statins, also falling solidly within the HM realm, can pay big dividends if used consistently.

Meanwhile, newer studies and clinical observations are widening the scope of considerations that should be on every hospitalist’s radar. Here are a few cited by stroke experts:

Permissive hypertension. After an ischemic stroke, the benefit of permissive hypertension is still widely misunderstood. Perhaps counterintuitively, high blood pressure after a stroke can help protect the area of the brain that is damaged but not yet dead, sometimes called the penumbra. “I highlight this because I think it’s a common mistake, that internists are very used to high blood pressure being a bad thing,” says Andrew Josephson, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology and director of the neurohospitalist program at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center. “And in general, it is; it’s a cause of stroke. But once somebody has a stroke, in the acute period, it’s important to allow the blood pressure to be high.”

Atrial fibrillation. The accepted role of atrial fibrillation in stroke is evolving. Research suggests that the common but often preventable arrhythmia is an important cause of stroke in about 15% to 20% of cases.9 By the time of hospital discharge, however, Dr. Josephson says physicians haven’t established a cause in about 1 in 4 cases. For these “cryptogenic strokes,” he says, doctors have long suspected that atrial fibrillation not picked up during the initial EKG or by the monitoring with cardiac telemetry could be a major cause.

Recent observations suggest that a longer monitoring period of up to 30 days may uncover atrial fibrillation in a sizable fraction of those patients, highlighting the importance of keeping a close eye on stroke patients both in the hospital and beyond. “It’s very important to identify, because atrial fibrillation changes what we do for folks to prevent a second stroke,” Dr. Josephson explains. Instead of anti-platelet medicine like aspirin, patients with atrial fibrillation often receive anticoagulants like warfarin, or the more recently approved dabigatran and rivaroxaban.

Transient ischemic attack. Improvements in imaging techniques like MRI have likewise begun to shift how stroke patients are treated. For example, Dr. Likosky says, medicine is moving away from a time-based definition of transient ischemic attack (TIA), in which symptoms resolve within 24 hours, to a tissue-based definition. Recent MRI imaging has uncovered evidence of a new infarction in more than half of patients initially diagnosed with TIA.10

“If they do have an infarction on their scan, even if they had symptoms that only lasted for five minutes, that’s a stroke,” Dr. Josephson says. And even a true TIA, he says, represents “a kind of stroke where you got really lucky and you’re not left with deficits, but the risk is still very high.” Accordingly, more patients with TIA are being admitted to the hospital to receive a full workup and preventive treatment. “We think that by evaluating these people urgently, we can reduce the risk of having a stroke by maybe 75% over a three-month time period,” Dr. Josephson says.

Hemorrhagic stroke. To date, the vast majority of patients with hemorrhagic stroke (which accounts for only 13% of all stroke cases) have been managed by neurosurgeons and neurologists. But here, too, Dr. Likosky says the picture could be changing. Recent findings that surgical treatment of intracranial hemorrhaging might not benefit many patients could shift the care paradigm toward a medical management strategy that involves more hospitalists.

Innovations Aplenty

The increasing complexity of stroke care and uneven distribution of resources and expertise have helped fuel several important innovations in delivery, most notably telestroke and neurohospital medicine. Both are being driven, in part, by an increased awareness of time-sensitive interventions and a frequent lack of on-site neurologists at smaller and more rural facilities. If telestroke programs are expanding the reach of neurologists, neurohospitalists are helping to fill the gaps in inpatient stroke care.

Amid the changes, one element is proving a necessary constant: a team approach that relies heavily on the HM emphasis on quality metrics, intensive monitoring, and careful coordination. Who better to lead the charge than hospitalists, says Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “They’re the ones who are in the hospital, and when these patients go bad, they go bad fast,” she says.

More broadly, Dr. Jensen says, hospitalists should get in on the ground floor when their facility seeks certification as a primary or a comprehensive stroke center. “And they need to make sure that the hospital isn’t just trying to get the sexy elements—the guy with the cath or the gal with the cath who can pull the clot out—but that they have a complete program that involves the care of the patient after they’ve had the procedure done,” she says.

As healthcare reform efforts are making clear, the responsibility doesn’t end after discharge, either. The Affordable Care Act includes a hospital readmission reduction program that will kick in this October, with penalties for hospitals posting unacceptably high 30-day readmission rates. Amy Kind, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Geriatrics at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, is convinced that a key contributor to high rehospitalization rates among stroke patients may be the woefully incomplete nature of discharge communication.

—Mary E. Jensen, MD, professor of radiology and neurosurgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Dr. Kind, for example, has found a disturbing pattern in communication regarding issues like dysphagia, a common complication among stroke patients and an important risk factor for pneumonia. Countering the risk usually requires such measures as putting patients on a special diet or elevating the head of their bed. “We looked at the quality of the communication of that information in discharge summaries, and it’s just abysmal. It’s absolutely abysmal,” she says. Without clear directives to providers in the next setting of care, such as a skilled-nursing facility, patients could be erroneously put back on a regular diet and aspirate, sending them right back to the hospital.

As one potential solution, Dr. Kind’s team is developing a multidisciplinary stroke discharge summary tool that automatically imports elements like speech-language pathology and dietary recommendations. Although most discharge communication may focus on more visible issues and interventions, Dr. Kind argues that some of the “bread and butter” concerns might ultimately prove just as important for long-term patient outcomes.

Karim Godamunne, MD, MBA, SFHM, vice president of clinical systems integration and medical director of Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta, sees telemedicine as another potential tool to help reach patients after discharge, especially those who haven’t received follow-up care from a primary-care physician (PCP). “We need to be the champions at our hospitals for improving care processes, and we need to work in partnership with the nurses and the other professionals,” Dr. Godamunne says. “As a group, we can really make a difference, and stroke is one of those areas in which we can truly contribute.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Freeman WD, Dawson SB, Raper C, Thiemann K, et al. Neurohospitalists reduce length of stay for patients with ischemic stroke. The Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(2): 67-70.

- Howrey BT, Kuo Y-F, Goodwin JS. Association of care by hospitalists on discharge destination and 30-day outcomes after acute ischemic stroke. Medical Care. 2011;49(8): 701-707.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

- Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728.

- Plauth WH, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 111(3):247-254.

- Dickerson LM, Carek PJ, Quattlebaum RG. Prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76(3):382-388.

- Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL, et al. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123(7):750-758.

- Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, et al. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317-1329.

- Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e91.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack—proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:993-1003.

Is Hospitalist Proficiency in Bedside Procedures in Decline?

It’s 3:30 p.m. You’ve seen your old patients, holdovers, and an admission, but you haven’t finished your notes yet. Lunch was an afterthought between emails about schedule changes for the upcoming year. Two pages ring happily from your belt, the first from you-know-who in the ED, and the next from a nurse: “THORA SUPPLIES AT BEDSIDE SINCE THIS AM—WHEN WILL THIS HAPPEN?” The phone number on the wall for the on-call radiologist beckons...

An all-too-familiar situation for hospitalists across the country, this awkward moment raises a series of difficult questions:

Should I set aside time from my day to perform a procedure that could be time-consuming?

- Do I feel confident I can perform this procedure safely?

- Am I really the best physician to provide this service?

- As hospitalists are tasked with an ever-increasing array of responsibilities, answering the call of duty for bedside procedures is becoming more difficult for some.

A Core Competency

“The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine,” authored by a group of HM thought leaders, was published as a supplement to the January/February 2006 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies include such bedside procedures as arthrocentesis, paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and vascular (arterial and central venous) access (see “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: Procedures,” below). Although the authors stressed that the core competencies are to be viewed as a resource rather than as a set of requirements, the inclusion of bedside procedures emphasized the importance of procedural skills for future hospitalists.

“[Hospitalists] are in a perfect spot to continue to perform procedures in a structured manner,” says Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety. “As agents of quality and safety, hospitalists should continue to perform this clinically necessary service.”

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and an academic hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), not only agrees that bedside procedures should be a core competency, but he also says hospitalists are the most appropriate providers of these services.

“I think this is part of hospital medicine. We’re in the hospital, [and] that’s what we do,” Dr. Barsuk says. Other providers, such as interventional radiologists, “really don’t understand why I’m doing [a procedure]. They understand it’s safe to do it, but they might not understand all the indications for it, and they certainly don’t understand the interpretation of the tests they’re sending.”

Despite the goals set forth by the core competencies and authorities in procedural safety, the reality of who actually performs bedside procedures is somewhat murky and varies greatly by institution. Many point to HM program setting (urban vs. rural) or structure (academic vs. community) to explain variance, but often it is other factors that determine whether hospitalists are actually preforming bedside procedures regularly.

Where Does HM Perform Procedures?

Community hospitalists, with strong support from interventional radiologists and subspecialists, often find it more efficient—even necessary, considering their patient volumes—to leave procedures to others. Community hospitalists with ICU admitting privileges, intensivists, and other HM subgroups say that being able to perform procedures should be a prerequisite for employment. Hospitalists in rural communities say they are doing procedures because they are “the only game in town.”

“Sometimes you are the only one available, and you are called upon to stretch your abilities,” says Beatrice Szantyr, MD, FAAP, a community hospitalist and pediatrician in Lincoln, Maine, who has practiced most of her career in rural settings.

Academic hospitalists in large, research-based HM programs can, paradoxically, find themselves performing fewer procedures as residents often take the lead on the majority of such cases. Conversely, academic hospitalists in large, nonteaching programs often find themselves called on to perform more bedside procedures.

No matter the setting, the simplicity of being the physician to recognize the need for a procedure, perform it, and interpret the results is undeniably efficient and “clean,” according to authorities on inpatient bedside procedures. Having to consult other physicians, optimize the patient’s lab values to their standards (a common issue with interventional radiologists), and adhere to their work schedules can often delay procedures unnecessarily.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director, University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety

“Hospitalists care for floor and ICU patients in many hospitals, and the inability to perform bedside procedures delays patient care,” says Dr. Nilam Soni, an academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago and a recognized expert on procedural safety.

Dr. Soni notes that when it comes to current techniques, many hospitalists suffer from a knowledge deficit. “The introduction of ultrasound for guidance of bedside procedures has been shown to improve the success and safety of certain procedures,” he says, “but the majority of practicing hospitalists did not learn how to use ultrasound for procedure guidance during residency.”

Heterogeneity of Training, Experience, and Skill

While all hospitalists draw upon different bases of training and experience, the heterogeneity of training, confidence, and inherent skill is greatest when it comes to bedside procedures. Mirroring the heterogeneity at the individual level, hospitalist programs vary greatly on the requirements placed on their staffs in regards to procedural skill and privileging.

Such research-driven programs as Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston often find requiring maintenance of privileges in bedside procedures to be difficult, says Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedural education at BWH. In fact, a new procedure service being created there will be staffed mainly with ED physicians. On the flipside, most community hospitalist programs leave the task of procedural “policing” to the hospital’s medical staff affairs office.

At the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center, the HM group is instituting a division standard in which hospitalists maintain privileging and proficiency in a core group of bedside procedures. Other large hospitalist groups have created “proceduralist” subgroups that shoulder the burden of trainee education, as well as provide a resource for less skilled or less experienced inpatient providers.

“If you have a big group, you could have a dedicated procedure service and have a core group of hospitalists who are experts in procedure,” Dr. Barsuk says. “But it needs to be self-sustaining.” Once started, Dr. Barsuk says, proceduralist groups would continue to provide hospitals with ongoing return-on-investment (ROI) benefit.

Variability in procedure volume and payor mix, however, can make it hard for HM groups to demonstrate to hospital leadership a satisfactory ROI for a proceduralist program. Financial backing from grant support or a high-volume procedure—such as paracentesis in hospitals with large hepatology programs—can nurture starting proceduralist programs until all procedural revenues can justify the costs. Lower ROI can also be justified by showing improvement in quality indices—such as CLABSI rates—reduced time to procedures, and reduced costs compared to other subspecialists offering similar services.

“I’m of the firm belief that we can reduce costs by doing the procedures at the bedside rather than referring them to departments such as interventional radiology (IR),” Dr. Barsuk says. “What you would have to do is show the institution that it costs more money to have IR do [bedside procedures].”

National Response

—Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, academic hospitalist, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

Filling in the procedural training gaps found on the local level, such national organizations as SHM have stepped in to provide education and support for hospitalists yearning for training. Since its inception, an SHM annual meeting pre-course that focuses on hand-held ultrasound and invasive procedures has consistently been one of the first to sell out. Other national organizations, such as ACP and its annual meeting, have seen similar interest in their courses on ultrasound-guided procedures.

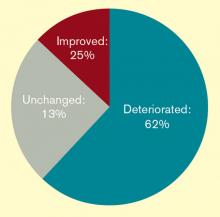

The popularity of this continuing education bears out a worrisome trend: Hospitalists feel they are losing their procedural skills. An online survey conducted by The Hospitalist in May 2011 found that a majority of respondents (62%) had experienced deterioration of their procedural skills in the past five years; only 25% said they experienced improvement over the same period.

Historically, general internists have claimed bedside procedures as their domain. As stated dispassionately in the 1978 book The House of God, “There is no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14G needle and a good strong arm.”1 Yet much has changed since Samuel Shem’s apocryphal description of medical residency training.

Most notably, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not only progressively restricted inpatient hours and patient loads for residents, but also increased the requirements for outpatient training. Some feel the balance of inpatient and outpatient training has tipped too far toward the latter in medicine residency programs, especially in light of the growing popularity of the hospitalist career path amongst new residency program graduates. This stands in contrast to ED training programs, which have embraced focused procedures training more readily.

“Adult care appears to be diverging into two career tacks as a result of external forces, of which we have limited control over, “ says Michael Beck, MD, a pediatric and adult hospitalist at Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa. “With new career choices emerging for graduates, the same square-peg, round-hole residency training should not exist.”

Dr. Beck advocates continuing an ongoing trend of “track” creation in residency programs, which allow trainees to focus training on their planned career path. Hospitalist tracks already exist in many medicine programs, including those at Cleveland Clinic and Northwestern. But many other factors limit the opportunity for trainees to obtain experience with bedside procedures, including competition with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Even the increasing availability of ancillary phlebotomy and IV-start teams can increase a resident’s anxiety about procedures.

“By the time my residency was over [in 1993] and the work restrictions were beginning, hospital employees were doing all these tasks, making the residents less comfortable with hurting a patient when it was therapeutically necessary,” says Katharine Deiss, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Interns who came from medical schools without extensive ancillary services in their teaching hospitals, she adds, were more comfortable with invasive procedures.

ACGME has sent a subtle message by decreasing emphasis on procedural skills by eradicating the requirement of showing manual proficiency in most bedside procedures as a requirement for certification. The omission has left individual residency programs and hospitalist groups to determine training and proficiency requirements for more invasive bedside procedures without a national standard.

In an editorial in the March 2007 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine, F. Daniel Duffy, MD, and Eric Holmboe, MD, wrote that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) could only give a “qualified ‘yes’” to the question of whether residents should be trained in procedures they may not perform in practice. Although the authors asserted that the relaxed ABIM policy was “an important but small step toward revamping procedure skill training during residency,” others say it portrays an image of the ABIM de-emphasizing the importance of procedural training.

In addition, the recently established Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway to ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) has no requirement to show proficiency in bedside procedures.

“The absence of the procedural requirement in no way constitutes a statement that procedural skills are not important,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and residency program director at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee, and former SHM president. “Rather, it is merely a practical issue with respect to making the MOC process applicable to all physicians engaged in hospital medicine (i.e. many hospitalists do not do procedures) while still making the MOC focused on the skill sets that are common for physicians doing hospital medicine.”

Once released into the world, even if trained well in residency, hospitalists can find it difficult to maintain their skills. In community and nonteaching settings, the pressure to admit and discharge in a timely manner can make procedures seem like the easiest corner to cut. Before long, it has been months since they have laid eyes on a needle of any sort. Many begin to develop performance anxiety.

In teaching hospitals, academic hospitalists often are called upon to participate in quality improvement (QI) and research efforts, which take time away from clinical rotations. Once there, it can be easy for a ward attending to rely upon a well-trained resident to supervise interns doing procedures. The lack of first-hand or even supervisory experience can lead to many academic hospitalists losing facility with procedures, with potentially disastrous results.

“In order to supervise a group of residents, the attending needs to be technically proficient and able to salvage a botched, or failed, procedure,” UM-JMH’s Dr. Lenchus says. “To this end, we strictly limit who can attend on the service.”

So what’s a residency or HM program director to do in the face of wavering support nationally, and sometimes locally, for maintaining procedural skills for hospitalists and trainees? Many hospitalists in teaching hospitals say it’s critical for clinicians to “get their own house in order,” to maintain procedural standards of proficiency with ongoing training, education, and verification.

“The profession now needs to redesign procedural training across the continuum of education and a lifetime of practice,” Drs. Duffy and Holmboe editorialized in the March 2007 Annals paper. “This approach would recognize the varied settings of internal-medicine practice and offer manual skills training to those whose practice settings require such skills.” Hospitalists can partner with medicine residency program leaders to provide procedural education and training to residents, either as a standalone elective or as a more general resource.

Hospitalists in such teaching hospitals as UCSD, Brigham and Women’s, UM-JMH, and Northwestern are leading efforts to provide procedural education to medical students, residents, and attendings. Training takes many forms, including formal procedural electives, required procedure rotations, or even brief one- or two-day courses in procedural skills at a simulation center.

Utilizing simulation training has been shown in many studies to be helpful in establishing procedural skills in learners of all training levels. Dr. Barsuk and his colleagues at Northwestern published studies in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2008 and 2009 showing that simulation training of residents was effective in improving skills in thoracentesis and central venous catheterization, respectively.3,4

In the community hospital setting, requirements for procedural skills can vary greatly based on the institution. For those community programs requiring procedural skills of their hospitalists, the clear definition of procedural training and requirements at the time of hiring is critical. Even after vetting a hospitalist’s procedural skills at hire, however, community programs should consider monitoring procedural skills and provide ongoing time and money for CME focused on procedural skills.

Currently, most hospitals depend on the honesty of individual physicians during the privileging process for bedside procedures. Even when the skills of physicians begin to wane, most are reluctant to voluntarily give up their procedure privileges.

“I think it would be pretty unusual for a hospitalist to relinquish their privileges,” Dr. Barsuk admits. But ideally, physicians who relinquish their privileges due to lack of experience could get retrained in simulation centers, then reproctored in order to regain their privileges. Northwestern established the Center for Simulation Technology and Immersive Learning as a resource for simulation training both locally and nationally.

Establishing an environment that supports hospitalists performing bedside procedures is critical. This includes the need to limit hospitalist workload to ensure adequate time to meet the procedural needs of patients. Providing easy access to the tools necessary to perform bedside procedures (e.g. portable ultrasound and pre-packaged procedure trays) helps avoid additional hurdles.

Academic hospitalist programs can serve as a regional resource by developing ongoing procedure mastery programs for hospitalists in their communities, as many smaller institutions do not have the resources to provide ongoing training in bedside procedures. This process can be tedious, but it should not be humiliating.

If the popularity of the SHM pre-course in bedside ultrasound and procedures is any indication, when given the opportunity to receive protected time for procedure training, most hospitalists will likely jump at the chance.

Dr. Chang is an associate clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Diego Medical Center. He is also a member of Team Hospitalist.

References

- Shem S. The House of God. New York: Dell Publishing; 1978.

- Duffy FD, Holmboe ES. What procedures should internists do? Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):392-393.

- Wayne DB, Barsuk JH, O’Leary KJ, Fudala MJ, McGaghie WC. Mastery learning of thoracentesis skills by internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(1):48-54.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397–403.

It’s 3:30 p.m. You’ve seen your old patients, holdovers, and an admission, but you haven’t finished your notes yet. Lunch was an afterthought between emails about schedule changes for the upcoming year. Two pages ring happily from your belt, the first from you-know-who in the ED, and the next from a nurse: “THORA SUPPLIES AT BEDSIDE SINCE THIS AM—WHEN WILL THIS HAPPEN?” The phone number on the wall for the on-call radiologist beckons...

An all-too-familiar situation for hospitalists across the country, this awkward moment raises a series of difficult questions:

Should I set aside time from my day to perform a procedure that could be time-consuming?

- Do I feel confident I can perform this procedure safely?

- Am I really the best physician to provide this service?

- As hospitalists are tasked with an ever-increasing array of responsibilities, answering the call of duty for bedside procedures is becoming more difficult for some.

A Core Competency

“The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine,” authored by a group of HM thought leaders, was published as a supplement to the January/February 2006 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies include such bedside procedures as arthrocentesis, paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and vascular (arterial and central venous) access (see “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: Procedures,” below). Although the authors stressed that the core competencies are to be viewed as a resource rather than as a set of requirements, the inclusion of bedside procedures emphasized the importance of procedural skills for future hospitalists.

“[Hospitalists] are in a perfect spot to continue to perform procedures in a structured manner,” says Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety. “As agents of quality and safety, hospitalists should continue to perform this clinically necessary service.”

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and an academic hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), not only agrees that bedside procedures should be a core competency, but he also says hospitalists are the most appropriate providers of these services.

“I think this is part of hospital medicine. We’re in the hospital, [and] that’s what we do,” Dr. Barsuk says. Other providers, such as interventional radiologists, “really don’t understand why I’m doing [a procedure]. They understand it’s safe to do it, but they might not understand all the indications for it, and they certainly don’t understand the interpretation of the tests they’re sending.”

Despite the goals set forth by the core competencies and authorities in procedural safety, the reality of who actually performs bedside procedures is somewhat murky and varies greatly by institution. Many point to HM program setting (urban vs. rural) or structure (academic vs. community) to explain variance, but often it is other factors that determine whether hospitalists are actually preforming bedside procedures regularly.

Where Does HM Perform Procedures?

Community hospitalists, with strong support from interventional radiologists and subspecialists, often find it more efficient—even necessary, considering their patient volumes—to leave procedures to others. Community hospitalists with ICU admitting privileges, intensivists, and other HM subgroups say that being able to perform procedures should be a prerequisite for employment. Hospitalists in rural communities say they are doing procedures because they are “the only game in town.”

“Sometimes you are the only one available, and you are called upon to stretch your abilities,” says Beatrice Szantyr, MD, FAAP, a community hospitalist and pediatrician in Lincoln, Maine, who has practiced most of her career in rural settings.

Academic hospitalists in large, research-based HM programs can, paradoxically, find themselves performing fewer procedures as residents often take the lead on the majority of such cases. Conversely, academic hospitalists in large, nonteaching programs often find themselves called on to perform more bedside procedures.

No matter the setting, the simplicity of being the physician to recognize the need for a procedure, perform it, and interpret the results is undeniably efficient and “clean,” according to authorities on inpatient bedside procedures. Having to consult other physicians, optimize the patient’s lab values to their standards (a common issue with interventional radiologists), and adhere to their work schedules can often delay procedures unnecessarily.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director, University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety

“Hospitalists care for floor and ICU patients in many hospitals, and the inability to perform bedside procedures delays patient care,” says Dr. Nilam Soni, an academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago and a recognized expert on procedural safety.

Dr. Soni notes that when it comes to current techniques, many hospitalists suffer from a knowledge deficit. “The introduction of ultrasound for guidance of bedside procedures has been shown to improve the success and safety of certain procedures,” he says, “but the majority of practicing hospitalists did not learn how to use ultrasound for procedure guidance during residency.”

Heterogeneity of Training, Experience, and Skill

While all hospitalists draw upon different bases of training and experience, the heterogeneity of training, confidence, and inherent skill is greatest when it comes to bedside procedures. Mirroring the heterogeneity at the individual level, hospitalist programs vary greatly on the requirements placed on their staffs in regards to procedural skill and privileging.

Such research-driven programs as Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston often find requiring maintenance of privileges in bedside procedures to be difficult, says Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedural education at BWH. In fact, a new procedure service being created there will be staffed mainly with ED physicians. On the flipside, most community hospitalist programs leave the task of procedural “policing” to the hospital’s medical staff affairs office.

At the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center, the HM group is instituting a division standard in which hospitalists maintain privileging and proficiency in a core group of bedside procedures. Other large hospitalist groups have created “proceduralist” subgroups that shoulder the burden of trainee education, as well as provide a resource for less skilled or less experienced inpatient providers.

“If you have a big group, you could have a dedicated procedure service and have a core group of hospitalists who are experts in procedure,” Dr. Barsuk says. “But it needs to be self-sustaining.” Once started, Dr. Barsuk says, proceduralist groups would continue to provide hospitals with ongoing return-on-investment (ROI) benefit.

Variability in procedure volume and payor mix, however, can make it hard for HM groups to demonstrate to hospital leadership a satisfactory ROI for a proceduralist program. Financial backing from grant support or a high-volume procedure—such as paracentesis in hospitals with large hepatology programs—can nurture starting proceduralist programs until all procedural revenues can justify the costs. Lower ROI can also be justified by showing improvement in quality indices—such as CLABSI rates—reduced time to procedures, and reduced costs compared to other subspecialists offering similar services.