User login

HM@15 - Is Hospital Medicine a Good Bet for Improving Patient Satisfaction?

At first glance, the deck might seem hopelessly stacked against hospitalists with regard to patient satisfaction. HM practitioners lack the long-term relationship with patients that many primary-care physicians (PCPs) have established. Unlike surgeons and other specialists, they tend to care for those patients—more complicated, lacking a regular doctor, or admitted through the ED, for example—who are more inclined to rate their hospital stay unfavorably.1 They may not even be accurately remembered by patients who encounter multiple doctors during the course of their hospitalization.2 And hospital information systems can misidentify the treating physician, while the actual surveys used to gauge hospitalists have been imperfect at best.3

And yet, the hospitalist model has evolved substantially on the question of how it can impact patient perceptions of care.

Initially, hospitalist champions adopted a largely defensive posture: The model would not negatively impact patient satisfaction as it delivered on efficiency—and later on quality. The healthcare system, however, is beginning to recognize the hospitalist as part of a care “team” whose patient-centered approach might pay big dividends in the inpatient experience and, eventually, on satisfaction scores.

“I think the next phase, which is a focus on the hospitalist as a team member and team builder, is going to be key,” says William Southern, MD, MPH, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y.

Recent studies suggest that hospitalists are helping to design and test new tools that will not only improve satisfaction, but also more fairly assess the impact of individual doctors. As the maturation process continues, experts say, hospitalists have an opportunity to influence both provider-based interventions and more programmatic decision-making that can have far-reaching effects. Certainly, the hand dealt to hospitalists is looking more favorable even as the ante has been raised with Medicare programs like value-based purchasing, and its pot of money tied to patient perceptions of care.

So how have hospitalists played their cards so far?

A Look at the Evidence

In its early years, the HM model faced a persistent criticism: Replacing traditional caregivers with these new inpatient providers in the name of efficiency would increase handoffs and, therefore, discontinuities of care delivered by a succession of unfamiliar faces. If patients didn’t see their PCP in the hospital, the thinking went, they might be more disgruntled at being tended to by hospitalists, leading to lower satisfaction scores.4

A particularly heated exchange played out in 1999 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Farris A. Manian, MD, MPH, of Infectious Disease Consultants in St. Louis wrote in one letter, “I am particularly concerned about what impressionable house-staff members will learn from hospitalists who place an inordinate emphasis on cost rather than the quality of patient care or teaching.”5

A few subsequent studies, however, hinted that such concerns might be overstated. A 2000 analysis in the American Journal of Medicine that examined North Mississippi Health Services in Tupelo, for instance, found that care administered by hospitalists led to a shorter length of stay and lower costs than care delivered by internists. Importantly, the study found that patient satisfaction was similar for both models, while quality metrics were likewise equal or even tilted slightly toward hospitalists.6

In their influential 2002 review of a profession that was only a half-decade old, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, MPH, FACP from the University of California at San Francisco reinforced the message that HM wouldn’t lead to unhappy patients. “Empirical research supports the premise that hospitalists improve inpatient efficiency without harmful effects on quality or patient satisfaction,” they asserted.7

Among pediatric patients, a 2005 review found that “none of the four studies that evaluated patient satisfaction found statistically significant differences in satisfaction with inpatient care. However, two of the three evaluations that did assess parents’ satisfaction with care provided to their children found that parents were more satisfied with some aspects of care provided by hospitalists.”8

—William Southern, MD, chief, division of hospital medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y.

Similar findings were popping up around the country: Replacing an internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant/hospitalist model at Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Coney Island Hospital did not adversely impact patient satisfaction, while it significantly improved mortality.9 Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston likewise reported no change in patient satisfaction in a study comparing a physician assistant/hospitalist service with traditional house staff services.10

The shift toward a more proactive position on patient satisfaction is exemplified within a 2008 white paper, “Hospitalists Meeting the Challenge of Patient Satisfaction,” written by a group of 19 private-practice HM experts known as The Phoenix Group.3 The paper acknowledged the flaws and limitations of existing survey methodologies, including Medicare’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores. Even so, the authors urged practice groups to adopt a team-oriented approach to communicate to hospital administrations “the belief that hospitalists are in the best position to improve survey scores overall for the facility.”

Carle Foundation Hospital in Urbana, Ill., is now publicly advertising its HM service’s contribution to high patient satisfaction scores on its website, and underscoring the hospitalists’ consistency, accessibility, and communication skills. “The hospital is never without a hospitalist, and our nurses know that they can rely on them,” says Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations. “They’re available, they’re within a few minutes away, and patients’ needs get met very efficiently and rapidly.”

As a result, she says, their presence can lead to higher scores in patients’ perceptions of communication.

Hospitalists also have been central to several safety initiatives at Carle. Napoleon Knight, MD, medical director of hospital medicine and associate vice president for quality, says the HM team has helped address undiagnosed sleep apnea and implement rapid responses, such as “Code Speed.” Caregivers or family members can use the code to immediately call for help if they detect a downturn in a patient’s condition.

The ongoing initiatives, Dr. Knight and Barnes say, are helping the hospital improve how patients and their loved ones perceive care as Carle adapts to a rapidly shifting healthcare landscape. “With all of the changes that seem to be coming from the external environment weekly, we want to work collaboratively to make sure we’re connected and aligned and communicating in an ongoing fashion so we can react to all of these changes,” Dr. Knight says.

Continued below...

A Hopeful Trend

So far, evidence that the HM model is more broadly raising patient satisfaction scores is largely anecdotal. But a few analyses suggest the trend is moving in the right direction. A recent study in the American Journal of Medical Quality, for instance, concludes that facilities with hospitalists might have an advantage in patient satisfaction with nursing and such personal issues as privacy, emotional needs, and response to complaints.11 The study also posits that teaching facilities employing hospitalists could see benefits in overall satisfaction, while large facilities with hospitalists might see gains in satisfaction with admissions, nursing, and tests and treatments.

Brad Fulton, PhD, a researcher at South Bend, Ind.-based healthcare consulting firm Press Ganey and the study’s lead author, says the 30,000-foot view of patient satisfaction at the facility level can get foggy in a hurry due to differences in the kind and size of hospitalist programs. “And despite all of that fog, we’re still able to see through that and find something,” he says.

One limitation is that the study findings could also reflect differences in the culture of facilities that choose to add hospitalists. That caveat means it might not be possible to completely untangle the effect of an HM group on inpatient care from the larger, hospitalwide values that have allowed the group to set up shop. The wrinkle brings its own fascinating questions, according to Fulton. For example, is that kind of culture necessary for hospitalists to function as well as they do?

—Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Ill.

Such considerations will become more important as the healthcare system places additional emphasis on patient satisfaction, as Medicare’s value-based purchasing program is doing through its HCAHPS scores. With all the changes, success or failure on the patient experience front is going to carry “not just a reputational import, but also a financial impact,” says Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, director of Acute Care for the Elderly (ACE) Service at the University of Colorado Denver.

So how can HM fairly and accurately assess its own practitioners? “I think one starts by trying to apply some of the rigor that we have learned from our experience as hospitalists in quality improvement to the more warm and fuzzy field of patient experience,” Dr. Cumbler says. Many hospitals employ surveys supplied by consultants like Press Ganey to track the global patient satisfaction for their institution, he says.

“But for an individual hospitalist or hospitalist group, that kind of tool often lacks both the specificity and the timeliness necessary to make good decisions about impact of interventions on patient satisfaction,” he says.

Mark Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, agrees that such imprecision could lead to unfair assessments. “You can imagine a scenario where a patient actually liked their hospitalist very much,” he says, “but when they got the survey, they said [their stay] was terrible and the reasons being because maybe the nurse call button was not answered and the food was terrible and medications were given to them incorrectly, or it was noisy at night so they couldn’t sleep.”

A recent study by Dr. Williams and his colleagues, in which they employed a new assessment method called the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), confirmed the group’s suspicions: “that the results from the Press Ganey didn’t match up with the CAT, which was a direct assessment of the patient’s perception of the hospitalist’s communication skills,” he says.12

The validated tool, he adds, provides directed feedback to the physician based on the percentage of patients rating that provider as excellent, instead of on the average total score. Hospitalists have felt vindicated by the results. “They were very nervous because the hospital talked about basing an incentive off of the Press Ganey scores, and we said, ‘You can’t do that,’ because we didn’t feel they were accurate, and this study proved that,” Dr. Williams explains.

Fortunately, the message has reached researchers and consultants alike, and better tools are starting to reach hospitals around the country. At HM11 in May, Press Ganey unveiled a new survey designed to help patients assess the care delivered by two hospitalists, the average for inpatient stays. The item set is specific to HM functions, and includes the photo and name of each hospitalist, which Fulton says should improve the validity and accuracy of the data.

“The early response looks really good,” Fulton says, though it’s too early to say whether the tool, called Hospitalist Insight, will live up to its billing. If it proves its mettle, Fulton says, the survey could be used to reward top-performing hospitalists, and the growing dataset could allow hospitals to compare themselves with appropriate peer groups for fairer comparisons.

Meanwhile, researchers are testing out checklists to score hospitalist etiquette, and tracking and paging systems to help ensure continuity of care. They have found increased patient satisfaction when doctors engage in verbal communication during a discharge, in interdisciplinary team rounding, and in efforts to address religious and spiritual concerns.

Since 2000, when Montefiore’s hospitalist program began, Dr. Southern says the hospital has explained to patients the tradeoff accompanying the HM model. “I say something like this to every patient: ‘I know I’m not the doctor that you know, and you’re just meeting me. The downside is that you haven’t met me before and I’m a new face, but the upside is that if you need me during the day, I’m here all the time, I’m not someplace else. And so if you need something, I can be here quickly.’ ”

Being very explicit about that tradeoff, he says, has made patients very comfortable with the model of care, especially during a crisis moment in their lives. “I think it’s really important to say, ‘I know you don’t know me, but here’s the upside.’ And my experience is that patients easily understand that tradeoff and are very positive,” Dr. Southern says.

The Verdict

Available evidence suggests that practitioners of the HM model have pivoted from defending against early criticism that they may harm patient satisfaction to pitching themselves as team leaders who can boost facilitywide perceptions of care. So far, too little research has been conducted to suggest whether that optimism is fully warranted, but early signs look promising.

At facilities like Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, medical floors staffed by hospitalists are beginning to beat out surgical floors for the traveling patient satisfaction award. And experts like Dr. Cumbler are pondering how ongoing initiatives to boost scores can follow in the footsteps of efficiency and quality-raising efforts by making the transition from focusing on individual doctors to adopting a more programmatic approach. “What’s happening to that patient during the 23 hours and 45 minutes of their hospital day that you are not sitting by the bedside? And what influence should a hospitalist have in affecting that other 23 hours and 45 minutes?” he says.

Handoffs, discharges, communication with PCPs, and other potential weak points in maintaining high levels of patient satisfaction, Dr. Cumbler says, all are amenable to systems-based improvement. “As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to influence not only our one-one-one interaction with the patient, but also to influence that system of care in a way that patients will notice in a real and tangible way,” he says. “I think we’ve recognized for some time that a healthy heart but a miserable patient is not a healthy person.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist based in Seattle.

References

- Williams M, Flanders SA, Whitcomb WF. Comprehensive hospital medicine: an evidence based approach. Elsevier;2007:971-976.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

- Singer AS, et al. Hospitalists meeting the challenge of patient satisfaction. The Phoenix Group. 2008;1-5.

- Manian FA. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1362-1363.

- Correspondence. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;341:850-852.

- Davis KM, Koch KE, Harvey JK, et al. Effects of hospitalists on cost, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in a rural health system. Amer J Med. 2000;108(8):621-626.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487-494.

- Coffman J, Rundall TG. The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the United States (a research synthesis). Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:379–406.

- Dhuper S, Choksi S. Replacing an academic internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant-hospitalist model: a comparative analysis study. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(2):132-139.

- Roy CL, Liang CL, Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361-368.

- Fulton BR, Drevs KE, Ayala LJ, Malott DL Jr. Patient satisfaction with hospitalists: facility-level analyses. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):95-102.

- Ferranti DE, Makoul G, Forth VE, Rauworth J, Lee J, Williams MV. Assessing patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT). J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):522-527.

At first glance, the deck might seem hopelessly stacked against hospitalists with regard to patient satisfaction. HM practitioners lack the long-term relationship with patients that many primary-care physicians (PCPs) have established. Unlike surgeons and other specialists, they tend to care for those patients—more complicated, lacking a regular doctor, or admitted through the ED, for example—who are more inclined to rate their hospital stay unfavorably.1 They may not even be accurately remembered by patients who encounter multiple doctors during the course of their hospitalization.2 And hospital information systems can misidentify the treating physician, while the actual surveys used to gauge hospitalists have been imperfect at best.3

And yet, the hospitalist model has evolved substantially on the question of how it can impact patient perceptions of care.

Initially, hospitalist champions adopted a largely defensive posture: The model would not negatively impact patient satisfaction as it delivered on efficiency—and later on quality. The healthcare system, however, is beginning to recognize the hospitalist as part of a care “team” whose patient-centered approach might pay big dividends in the inpatient experience and, eventually, on satisfaction scores.

“I think the next phase, which is a focus on the hospitalist as a team member and team builder, is going to be key,” says William Southern, MD, MPH, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y.

Recent studies suggest that hospitalists are helping to design and test new tools that will not only improve satisfaction, but also more fairly assess the impact of individual doctors. As the maturation process continues, experts say, hospitalists have an opportunity to influence both provider-based interventions and more programmatic decision-making that can have far-reaching effects. Certainly, the hand dealt to hospitalists is looking more favorable even as the ante has been raised with Medicare programs like value-based purchasing, and its pot of money tied to patient perceptions of care.

So how have hospitalists played their cards so far?

A Look at the Evidence

In its early years, the HM model faced a persistent criticism: Replacing traditional caregivers with these new inpatient providers in the name of efficiency would increase handoffs and, therefore, discontinuities of care delivered by a succession of unfamiliar faces. If patients didn’t see their PCP in the hospital, the thinking went, they might be more disgruntled at being tended to by hospitalists, leading to lower satisfaction scores.4

A particularly heated exchange played out in 1999 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Farris A. Manian, MD, MPH, of Infectious Disease Consultants in St. Louis wrote in one letter, “I am particularly concerned about what impressionable house-staff members will learn from hospitalists who place an inordinate emphasis on cost rather than the quality of patient care or teaching.”5

A few subsequent studies, however, hinted that such concerns might be overstated. A 2000 analysis in the American Journal of Medicine that examined North Mississippi Health Services in Tupelo, for instance, found that care administered by hospitalists led to a shorter length of stay and lower costs than care delivered by internists. Importantly, the study found that patient satisfaction was similar for both models, while quality metrics were likewise equal or even tilted slightly toward hospitalists.6

In their influential 2002 review of a profession that was only a half-decade old, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, MPH, FACP from the University of California at San Francisco reinforced the message that HM wouldn’t lead to unhappy patients. “Empirical research supports the premise that hospitalists improve inpatient efficiency without harmful effects on quality or patient satisfaction,” they asserted.7

Among pediatric patients, a 2005 review found that “none of the four studies that evaluated patient satisfaction found statistically significant differences in satisfaction with inpatient care. However, two of the three evaluations that did assess parents’ satisfaction with care provided to their children found that parents were more satisfied with some aspects of care provided by hospitalists.”8

—William Southern, MD, chief, division of hospital medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y.

Similar findings were popping up around the country: Replacing an internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant/hospitalist model at Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Coney Island Hospital did not adversely impact patient satisfaction, while it significantly improved mortality.9 Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston likewise reported no change in patient satisfaction in a study comparing a physician assistant/hospitalist service with traditional house staff services.10

The shift toward a more proactive position on patient satisfaction is exemplified within a 2008 white paper, “Hospitalists Meeting the Challenge of Patient Satisfaction,” written by a group of 19 private-practice HM experts known as The Phoenix Group.3 The paper acknowledged the flaws and limitations of existing survey methodologies, including Medicare’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores. Even so, the authors urged practice groups to adopt a team-oriented approach to communicate to hospital administrations “the belief that hospitalists are in the best position to improve survey scores overall for the facility.”

Carle Foundation Hospital in Urbana, Ill., is now publicly advertising its HM service’s contribution to high patient satisfaction scores on its website, and underscoring the hospitalists’ consistency, accessibility, and communication skills. “The hospital is never without a hospitalist, and our nurses know that they can rely on them,” says Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations. “They’re available, they’re within a few minutes away, and patients’ needs get met very efficiently and rapidly.”

As a result, she says, their presence can lead to higher scores in patients’ perceptions of communication.

Hospitalists also have been central to several safety initiatives at Carle. Napoleon Knight, MD, medical director of hospital medicine and associate vice president for quality, says the HM team has helped address undiagnosed sleep apnea and implement rapid responses, such as “Code Speed.” Caregivers or family members can use the code to immediately call for help if they detect a downturn in a patient’s condition.

The ongoing initiatives, Dr. Knight and Barnes say, are helping the hospital improve how patients and their loved ones perceive care as Carle adapts to a rapidly shifting healthcare landscape. “With all of the changes that seem to be coming from the external environment weekly, we want to work collaboratively to make sure we’re connected and aligned and communicating in an ongoing fashion so we can react to all of these changes,” Dr. Knight says.

Continued below...

A Hopeful Trend

So far, evidence that the HM model is more broadly raising patient satisfaction scores is largely anecdotal. But a few analyses suggest the trend is moving in the right direction. A recent study in the American Journal of Medical Quality, for instance, concludes that facilities with hospitalists might have an advantage in patient satisfaction with nursing and such personal issues as privacy, emotional needs, and response to complaints.11 The study also posits that teaching facilities employing hospitalists could see benefits in overall satisfaction, while large facilities with hospitalists might see gains in satisfaction with admissions, nursing, and tests and treatments.

Brad Fulton, PhD, a researcher at South Bend, Ind.-based healthcare consulting firm Press Ganey and the study’s lead author, says the 30,000-foot view of patient satisfaction at the facility level can get foggy in a hurry due to differences in the kind and size of hospitalist programs. “And despite all of that fog, we’re still able to see through that and find something,” he says.

One limitation is that the study findings could also reflect differences in the culture of facilities that choose to add hospitalists. That caveat means it might not be possible to completely untangle the effect of an HM group on inpatient care from the larger, hospitalwide values that have allowed the group to set up shop. The wrinkle brings its own fascinating questions, according to Fulton. For example, is that kind of culture necessary for hospitalists to function as well as they do?

—Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Ill.

Such considerations will become more important as the healthcare system places additional emphasis on patient satisfaction, as Medicare’s value-based purchasing program is doing through its HCAHPS scores. With all the changes, success or failure on the patient experience front is going to carry “not just a reputational import, but also a financial impact,” says Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, director of Acute Care for the Elderly (ACE) Service at the University of Colorado Denver.

So how can HM fairly and accurately assess its own practitioners? “I think one starts by trying to apply some of the rigor that we have learned from our experience as hospitalists in quality improvement to the more warm and fuzzy field of patient experience,” Dr. Cumbler says. Many hospitals employ surveys supplied by consultants like Press Ganey to track the global patient satisfaction for their institution, he says.

“But for an individual hospitalist or hospitalist group, that kind of tool often lacks both the specificity and the timeliness necessary to make good decisions about impact of interventions on patient satisfaction,” he says.

Mark Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, agrees that such imprecision could lead to unfair assessments. “You can imagine a scenario where a patient actually liked their hospitalist very much,” he says, “but when they got the survey, they said [their stay] was terrible and the reasons being because maybe the nurse call button was not answered and the food was terrible and medications were given to them incorrectly, or it was noisy at night so they couldn’t sleep.”

A recent study by Dr. Williams and his colleagues, in which they employed a new assessment method called the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), confirmed the group’s suspicions: “that the results from the Press Ganey didn’t match up with the CAT, which was a direct assessment of the patient’s perception of the hospitalist’s communication skills,” he says.12

The validated tool, he adds, provides directed feedback to the physician based on the percentage of patients rating that provider as excellent, instead of on the average total score. Hospitalists have felt vindicated by the results. “They were very nervous because the hospital talked about basing an incentive off of the Press Ganey scores, and we said, ‘You can’t do that,’ because we didn’t feel they were accurate, and this study proved that,” Dr. Williams explains.

Fortunately, the message has reached researchers and consultants alike, and better tools are starting to reach hospitals around the country. At HM11 in May, Press Ganey unveiled a new survey designed to help patients assess the care delivered by two hospitalists, the average for inpatient stays. The item set is specific to HM functions, and includes the photo and name of each hospitalist, which Fulton says should improve the validity and accuracy of the data.

“The early response looks really good,” Fulton says, though it’s too early to say whether the tool, called Hospitalist Insight, will live up to its billing. If it proves its mettle, Fulton says, the survey could be used to reward top-performing hospitalists, and the growing dataset could allow hospitals to compare themselves with appropriate peer groups for fairer comparisons.

Meanwhile, researchers are testing out checklists to score hospitalist etiquette, and tracking and paging systems to help ensure continuity of care. They have found increased patient satisfaction when doctors engage in verbal communication during a discharge, in interdisciplinary team rounding, and in efforts to address religious and spiritual concerns.

Since 2000, when Montefiore’s hospitalist program began, Dr. Southern says the hospital has explained to patients the tradeoff accompanying the HM model. “I say something like this to every patient: ‘I know I’m not the doctor that you know, and you’re just meeting me. The downside is that you haven’t met me before and I’m a new face, but the upside is that if you need me during the day, I’m here all the time, I’m not someplace else. And so if you need something, I can be here quickly.’ ”

Being very explicit about that tradeoff, he says, has made patients very comfortable with the model of care, especially during a crisis moment in their lives. “I think it’s really important to say, ‘I know you don’t know me, but here’s the upside.’ And my experience is that patients easily understand that tradeoff and are very positive,” Dr. Southern says.

The Verdict

Available evidence suggests that practitioners of the HM model have pivoted from defending against early criticism that they may harm patient satisfaction to pitching themselves as team leaders who can boost facilitywide perceptions of care. So far, too little research has been conducted to suggest whether that optimism is fully warranted, but early signs look promising.

At facilities like Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, medical floors staffed by hospitalists are beginning to beat out surgical floors for the traveling patient satisfaction award. And experts like Dr. Cumbler are pondering how ongoing initiatives to boost scores can follow in the footsteps of efficiency and quality-raising efforts by making the transition from focusing on individual doctors to adopting a more programmatic approach. “What’s happening to that patient during the 23 hours and 45 minutes of their hospital day that you are not sitting by the bedside? And what influence should a hospitalist have in affecting that other 23 hours and 45 minutes?” he says.

Handoffs, discharges, communication with PCPs, and other potential weak points in maintaining high levels of patient satisfaction, Dr. Cumbler says, all are amenable to systems-based improvement. “As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to influence not only our one-one-one interaction with the patient, but also to influence that system of care in a way that patients will notice in a real and tangible way,” he says. “I think we’ve recognized for some time that a healthy heart but a miserable patient is not a healthy person.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist based in Seattle.

References

- Williams M, Flanders SA, Whitcomb WF. Comprehensive hospital medicine: an evidence based approach. Elsevier;2007:971-976.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

- Singer AS, et al. Hospitalists meeting the challenge of patient satisfaction. The Phoenix Group. 2008;1-5.

- Manian FA. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1362-1363.

- Correspondence. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;341:850-852.

- Davis KM, Koch KE, Harvey JK, et al. Effects of hospitalists on cost, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in a rural health system. Amer J Med. 2000;108(8):621-626.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487-494.

- Coffman J, Rundall TG. The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the United States (a research synthesis). Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:379–406.

- Dhuper S, Choksi S. Replacing an academic internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant-hospitalist model: a comparative analysis study. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(2):132-139.

- Roy CL, Liang CL, Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361-368.

- Fulton BR, Drevs KE, Ayala LJ, Malott DL Jr. Patient satisfaction with hospitalists: facility-level analyses. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):95-102.

- Ferranti DE, Makoul G, Forth VE, Rauworth J, Lee J, Williams MV. Assessing patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT). J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):522-527.

At first glance, the deck might seem hopelessly stacked against hospitalists with regard to patient satisfaction. HM practitioners lack the long-term relationship with patients that many primary-care physicians (PCPs) have established. Unlike surgeons and other specialists, they tend to care for those patients—more complicated, lacking a regular doctor, or admitted through the ED, for example—who are more inclined to rate their hospital stay unfavorably.1 They may not even be accurately remembered by patients who encounter multiple doctors during the course of their hospitalization.2 And hospital information systems can misidentify the treating physician, while the actual surveys used to gauge hospitalists have been imperfect at best.3

And yet, the hospitalist model has evolved substantially on the question of how it can impact patient perceptions of care.

Initially, hospitalist champions adopted a largely defensive posture: The model would not negatively impact patient satisfaction as it delivered on efficiency—and later on quality. The healthcare system, however, is beginning to recognize the hospitalist as part of a care “team” whose patient-centered approach might pay big dividends in the inpatient experience and, eventually, on satisfaction scores.

“I think the next phase, which is a focus on the hospitalist as a team member and team builder, is going to be key,” says William Southern, MD, MPH, SFHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y.

Recent studies suggest that hospitalists are helping to design and test new tools that will not only improve satisfaction, but also more fairly assess the impact of individual doctors. As the maturation process continues, experts say, hospitalists have an opportunity to influence both provider-based interventions and more programmatic decision-making that can have far-reaching effects. Certainly, the hand dealt to hospitalists is looking more favorable even as the ante has been raised with Medicare programs like value-based purchasing, and its pot of money tied to patient perceptions of care.

So how have hospitalists played their cards so far?

A Look at the Evidence

In its early years, the HM model faced a persistent criticism: Replacing traditional caregivers with these new inpatient providers in the name of efficiency would increase handoffs and, therefore, discontinuities of care delivered by a succession of unfamiliar faces. If patients didn’t see their PCP in the hospital, the thinking went, they might be more disgruntled at being tended to by hospitalists, leading to lower satisfaction scores.4

A particularly heated exchange played out in 1999 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Farris A. Manian, MD, MPH, of Infectious Disease Consultants in St. Louis wrote in one letter, “I am particularly concerned about what impressionable house-staff members will learn from hospitalists who place an inordinate emphasis on cost rather than the quality of patient care or teaching.”5

A few subsequent studies, however, hinted that such concerns might be overstated. A 2000 analysis in the American Journal of Medicine that examined North Mississippi Health Services in Tupelo, for instance, found that care administered by hospitalists led to a shorter length of stay and lower costs than care delivered by internists. Importantly, the study found that patient satisfaction was similar for both models, while quality metrics were likewise equal or even tilted slightly toward hospitalists.6

In their influential 2002 review of a profession that was only a half-decade old, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, MPH, FACP from the University of California at San Francisco reinforced the message that HM wouldn’t lead to unhappy patients. “Empirical research supports the premise that hospitalists improve inpatient efficiency without harmful effects on quality or patient satisfaction,” they asserted.7

Among pediatric patients, a 2005 review found that “none of the four studies that evaluated patient satisfaction found statistically significant differences in satisfaction with inpatient care. However, two of the three evaluations that did assess parents’ satisfaction with care provided to their children found that parents were more satisfied with some aspects of care provided by hospitalists.”8

—William Southern, MD, chief, division of hospital medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, N.Y.

Similar findings were popping up around the country: Replacing an internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant/hospitalist model at Brooklyn, N.Y.’s Coney Island Hospital did not adversely impact patient satisfaction, while it significantly improved mortality.9 Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston likewise reported no change in patient satisfaction in a study comparing a physician assistant/hospitalist service with traditional house staff services.10

The shift toward a more proactive position on patient satisfaction is exemplified within a 2008 white paper, “Hospitalists Meeting the Challenge of Patient Satisfaction,” written by a group of 19 private-practice HM experts known as The Phoenix Group.3 The paper acknowledged the flaws and limitations of existing survey methodologies, including Medicare’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) scores. Even so, the authors urged practice groups to adopt a team-oriented approach to communicate to hospital administrations “the belief that hospitalists are in the best position to improve survey scores overall for the facility.”

Carle Foundation Hospital in Urbana, Ill., is now publicly advertising its HM service’s contribution to high patient satisfaction scores on its website, and underscoring the hospitalists’ consistency, accessibility, and communication skills. “The hospital is never without a hospitalist, and our nurses know that they can rely on them,” says Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations. “They’re available, they’re within a few minutes away, and patients’ needs get met very efficiently and rapidly.”

As a result, she says, their presence can lead to higher scores in patients’ perceptions of communication.

Hospitalists also have been central to several safety initiatives at Carle. Napoleon Knight, MD, medical director of hospital medicine and associate vice president for quality, says the HM team has helped address undiagnosed sleep apnea and implement rapid responses, such as “Code Speed.” Caregivers or family members can use the code to immediately call for help if they detect a downturn in a patient’s condition.

The ongoing initiatives, Dr. Knight and Barnes say, are helping the hospital improve how patients and their loved ones perceive care as Carle adapts to a rapidly shifting healthcare landscape. “With all of the changes that seem to be coming from the external environment weekly, we want to work collaboratively to make sure we’re connected and aligned and communicating in an ongoing fashion so we can react to all of these changes,” Dr. Knight says.

Continued below...

A Hopeful Trend

So far, evidence that the HM model is more broadly raising patient satisfaction scores is largely anecdotal. But a few analyses suggest the trend is moving in the right direction. A recent study in the American Journal of Medical Quality, for instance, concludes that facilities with hospitalists might have an advantage in patient satisfaction with nursing and such personal issues as privacy, emotional needs, and response to complaints.11 The study also posits that teaching facilities employing hospitalists could see benefits in overall satisfaction, while large facilities with hospitalists might see gains in satisfaction with admissions, nursing, and tests and treatments.

Brad Fulton, PhD, a researcher at South Bend, Ind.-based healthcare consulting firm Press Ganey and the study’s lead author, says the 30,000-foot view of patient satisfaction at the facility level can get foggy in a hurry due to differences in the kind and size of hospitalist programs. “And despite all of that fog, we’re still able to see through that and find something,” he says.

One limitation is that the study findings could also reflect differences in the culture of facilities that choose to add hospitalists. That caveat means it might not be possible to completely untangle the effect of an HM group on inpatient care from the larger, hospitalwide values that have allowed the group to set up shop. The wrinkle brings its own fascinating questions, according to Fulton. For example, is that kind of culture necessary for hospitalists to function as well as they do?

—Lynn Barnes, vice president of hospital operations, Carle Foundation Hospital, Urbana, Ill.

Such considerations will become more important as the healthcare system places additional emphasis on patient satisfaction, as Medicare’s value-based purchasing program is doing through its HCAHPS scores. With all the changes, success or failure on the patient experience front is going to carry “not just a reputational import, but also a financial impact,” says Ethan Cumbler, MD, FACP, director of Acute Care for the Elderly (ACE) Service at the University of Colorado Denver.

So how can HM fairly and accurately assess its own practitioners? “I think one starts by trying to apply some of the rigor that we have learned from our experience as hospitalists in quality improvement to the more warm and fuzzy field of patient experience,” Dr. Cumbler says. Many hospitals employ surveys supplied by consultants like Press Ganey to track the global patient satisfaction for their institution, he says.

“But for an individual hospitalist or hospitalist group, that kind of tool often lacks both the specificity and the timeliness necessary to make good decisions about impact of interventions on patient satisfaction,” he says.

Mark Williams, MD, FACP, FHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, agrees that such imprecision could lead to unfair assessments. “You can imagine a scenario where a patient actually liked their hospitalist very much,” he says, “but when they got the survey, they said [their stay] was terrible and the reasons being because maybe the nurse call button was not answered and the food was terrible and medications were given to them incorrectly, or it was noisy at night so they couldn’t sleep.”

A recent study by Dr. Williams and his colleagues, in which they employed a new assessment method called the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), confirmed the group’s suspicions: “that the results from the Press Ganey didn’t match up with the CAT, which was a direct assessment of the patient’s perception of the hospitalist’s communication skills,” he says.12

The validated tool, he adds, provides directed feedback to the physician based on the percentage of patients rating that provider as excellent, instead of on the average total score. Hospitalists have felt vindicated by the results. “They were very nervous because the hospital talked about basing an incentive off of the Press Ganey scores, and we said, ‘You can’t do that,’ because we didn’t feel they were accurate, and this study proved that,” Dr. Williams explains.

Fortunately, the message has reached researchers and consultants alike, and better tools are starting to reach hospitals around the country. At HM11 in May, Press Ganey unveiled a new survey designed to help patients assess the care delivered by two hospitalists, the average for inpatient stays. The item set is specific to HM functions, and includes the photo and name of each hospitalist, which Fulton says should improve the validity and accuracy of the data.

“The early response looks really good,” Fulton says, though it’s too early to say whether the tool, called Hospitalist Insight, will live up to its billing. If it proves its mettle, Fulton says, the survey could be used to reward top-performing hospitalists, and the growing dataset could allow hospitals to compare themselves with appropriate peer groups for fairer comparisons.

Meanwhile, researchers are testing out checklists to score hospitalist etiquette, and tracking and paging systems to help ensure continuity of care. They have found increased patient satisfaction when doctors engage in verbal communication during a discharge, in interdisciplinary team rounding, and in efforts to address religious and spiritual concerns.

Since 2000, when Montefiore’s hospitalist program began, Dr. Southern says the hospital has explained to patients the tradeoff accompanying the HM model. “I say something like this to every patient: ‘I know I’m not the doctor that you know, and you’re just meeting me. The downside is that you haven’t met me before and I’m a new face, but the upside is that if you need me during the day, I’m here all the time, I’m not someplace else. And so if you need something, I can be here quickly.’ ”

Being very explicit about that tradeoff, he says, has made patients very comfortable with the model of care, especially during a crisis moment in their lives. “I think it’s really important to say, ‘I know you don’t know me, but here’s the upside.’ And my experience is that patients easily understand that tradeoff and are very positive,” Dr. Southern says.

The Verdict

Available evidence suggests that practitioners of the HM model have pivoted from defending against early criticism that they may harm patient satisfaction to pitching themselves as team leaders who can boost facilitywide perceptions of care. So far, too little research has been conducted to suggest whether that optimism is fully warranted, but early signs look promising.

At facilities like Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial Hospital, medical floors staffed by hospitalists are beginning to beat out surgical floors for the traveling patient satisfaction award. And experts like Dr. Cumbler are pondering how ongoing initiatives to boost scores can follow in the footsteps of efficiency and quality-raising efforts by making the transition from focusing on individual doctors to adopting a more programmatic approach. “What’s happening to that patient during the 23 hours and 45 minutes of their hospital day that you are not sitting by the bedside? And what influence should a hospitalist have in affecting that other 23 hours and 45 minutes?” he says.

Handoffs, discharges, communication with PCPs, and other potential weak points in maintaining high levels of patient satisfaction, Dr. Cumbler says, all are amenable to systems-based improvement. “As hospitalists, we are in a unique position to influence not only our one-one-one interaction with the patient, but also to influence that system of care in a way that patients will notice in a real and tangible way,” he says. “I think we’ve recognized for some time that a healthy heart but a miserable patient is not a healthy person.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist based in Seattle.

References

- Williams M, Flanders SA, Whitcomb WF. Comprehensive hospital medicine: an evidence based approach. Elsevier;2007:971-976.

- Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201.

- Singer AS, et al. Hospitalists meeting the challenge of patient satisfaction. The Phoenix Group. 2008;1-5.

- Manian FA. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1362-1363.

- Correspondence. Whither continuity of care? N Engl J Med. 1999;341:850-852.

- Davis KM, Koch KE, Harvey JK, et al. Effects of hospitalists on cost, outcomes, and patient satisfaction in a rural health system. Amer J Med. 2000;108(8):621-626.

- Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487-494.

- Coffman J, Rundall TG. The impact of hospitalists on the cost and quality of inpatient care in the United States (a research synthesis). Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:379–406.

- Dhuper S, Choksi S. Replacing an academic internal medicine residency program with a physician assistant-hospitalist model: a comparative analysis study. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(2):132-139.

- Roy CL, Liang CL, Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361-368.

- Fulton BR, Drevs KE, Ayala LJ, Malott DL Jr. Patient satisfaction with hospitalists: facility-level analyses. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2):95-102.

- Ferranti DE, Makoul G, Forth VE, Rauworth J, Lee J, Williams MV. Assessing patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT). J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):522-527.

Our Wake-Up Call

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality.

I suspect most of you have reviewed the study or at least heard about it. Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about the study. An article about the study appeared in American Medical Association News. Even National Public Radio ran a piece about the study on their show “Morning Edition.”

I am, of course, referring to the study by Kuo and Goodwin, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in early August.1

In this study, the authors looked at a sample of patients (5%) with primary-care physicians (PCPs) enrolled in Medicare who were cared for by their PCP or a hospitalist during a period from 2001 to 2006. The authors stated their underlying hypotheses as:

- Hospitalist care would be associated with costs shifting from the hospital to the post-hospital setting;

- Hospitalist care would be associated with a decrease in discharges directly to home; and

- Discontinuities of care associated with hospitalist care would lead to a greater rate of visits to the emergency room and readmissions to the hospital, resulting in increased Medicare costs.

Did the authors say hospitalist care cost more? They can’t possibly be correct, can they? Don’t all the hospitalist studies show that hospitalists provide the same quality of care as primary-care doctors, except the costs are lower and the hospital length of stay (LOS) is shorter when hospitalists care for patients?

The point here is that these investigators look at the care not only during a patient’s hospital stay, but also for 30 days after discharge. This is something that had not been done previously—at least not on this scale.

Focus on Facts

And what did the authors find? Patients cared for by hospitalists, as compared to their PCPs, had a shorter LOS and lower in-hospital costs, but these patients also were less likely to be discharged directly to home, less likely to see their PCPs post-discharge, and had more hospital readmissions, ED visits, and nursing home visits after discharge.

Since its release two months ago, I have heard a lot of discussion about the study. Here are a few of the comments I’ve heard:

- “This was an observational study. You can’t possibly remove all confounders in an observational study.”

- “The authors looked at a time period early in the hospitalist movement. If they did the study today, the results would be different.”

- “The additional costs hospitalists incurred were only $50 per patient. Wouldn’t you pay $50 more if the care was better?”

- “This is why hospitals hired hospitalists. They save money for the hospitals. What did they expect to find?”

I agree that observational studies have limitations (even the authors acknowledged this), but this doesn’t mean results from observational studies are invalid. Some of us don’t want to hear this, but this actually was a pretty well-done study with a robust statistical analysis. We should recognize the study has limitations and think about the results.

Kuo and Goodwin looked at data during a period of time early in the hospitalist movement; the results could be different if the study were to be repeated today. But we don’t know what the data would be today. I suppose the data could be better, worse, or about the same. The fact of the matter is that HM leaders—and most of the rest of us—knew that transitions of care, under the hospitalist model, were a potential weakness. How many times have you heard Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, and John Nelson, MD, MHM, talk about the potential “voltage drop” with handoffs?

The good news is that leaders in our field have done something about this. Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) is a program SHM has helped implement at dozens of hospitals across the country to address the issue of unnecessary hospital readmissions (www.hospitalmedicine. org/boost). Improving transitions of care and preventing unnecessary readmissions should be on the minds of all hospitalists. If your program and your hospital have not yet taken steps to address this issue, please let this be your wake-up call.

Show Me the Money

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality. I agree with you that it is hard to look at costs without looking at quality. Therein lies the basis for our nation’s move toward value-based purchasing of healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011).

When I hear hospitalists explain why the role of hospitalists was developed, the explanation often involves some discussion of cost and LOS reduction. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not that I believe HM has focused too much attention on cost reduction. I believe we have not focused enough on improving quality. This should not be surprising. Moving the bar on cost reduction is a lot easier than moving the bar on quality and patient safety. The first step toward improvement is an understanding of what you are doing currently. If your hospitalist group has not implemented a program to help its hospitalists measure the quality of care being provided, again, this is your wake-up call.

Last, but not least, for those of you who are not “surprised” by the results because of the belief that hospitalists were created to help the hospital save money and nothing more, I could not disagree with you more. I look at the roles that hospitalists have taken on in our nation’s hospitals, and I am incredibly proud to call myself a hospitalist.

Hospitalists are providing timely care when patients need it. Hospitalists are caring for patients without PCPs. Not only do hospitalists allow PCPs to provide more care in their outpatient clinics, but hospitalists also are caring for patients in ICUs in many places where there are not enough doctors sufficiently trained in critical care.

Rather than acting as an indictment on HM, I believe the Annals article makes a comment on the misalignment of incentives in our healthcare system.

It is 2011, not 1996; HM is here to stay. Most acute-care hospitals in America could not function without hospitalists. I applaud Kuo and Goodwin for doing the research and publishing their results. Let this be an opportunity for hospitalists around the country to think about how to implement systems to improve transitions of care and the quality of care we provide.

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

Reference

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality.

I suspect most of you have reviewed the study or at least heard about it. Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about the study. An article about the study appeared in American Medical Association News. Even National Public Radio ran a piece about the study on their show “Morning Edition.”

I am, of course, referring to the study by Kuo and Goodwin, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in early August.1

In this study, the authors looked at a sample of patients (5%) with primary-care physicians (PCPs) enrolled in Medicare who were cared for by their PCP or a hospitalist during a period from 2001 to 2006. The authors stated their underlying hypotheses as:

- Hospitalist care would be associated with costs shifting from the hospital to the post-hospital setting;

- Hospitalist care would be associated with a decrease in discharges directly to home; and

- Discontinuities of care associated with hospitalist care would lead to a greater rate of visits to the emergency room and readmissions to the hospital, resulting in increased Medicare costs.

Did the authors say hospitalist care cost more? They can’t possibly be correct, can they? Don’t all the hospitalist studies show that hospitalists provide the same quality of care as primary-care doctors, except the costs are lower and the hospital length of stay (LOS) is shorter when hospitalists care for patients?

The point here is that these investigators look at the care not only during a patient’s hospital stay, but also for 30 days after discharge. This is something that had not been done previously—at least not on this scale.

Focus on Facts

And what did the authors find? Patients cared for by hospitalists, as compared to their PCPs, had a shorter LOS and lower in-hospital costs, but these patients also were less likely to be discharged directly to home, less likely to see their PCPs post-discharge, and had more hospital readmissions, ED visits, and nursing home visits after discharge.

Since its release two months ago, I have heard a lot of discussion about the study. Here are a few of the comments I’ve heard:

- “This was an observational study. You can’t possibly remove all confounders in an observational study.”

- “The authors looked at a time period early in the hospitalist movement. If they did the study today, the results would be different.”

- “The additional costs hospitalists incurred were only $50 per patient. Wouldn’t you pay $50 more if the care was better?”

- “This is why hospitals hired hospitalists. They save money for the hospitals. What did they expect to find?”

I agree that observational studies have limitations (even the authors acknowledged this), but this doesn’t mean results from observational studies are invalid. Some of us don’t want to hear this, but this actually was a pretty well-done study with a robust statistical analysis. We should recognize the study has limitations and think about the results.

Kuo and Goodwin looked at data during a period of time early in the hospitalist movement; the results could be different if the study were to be repeated today. But we don’t know what the data would be today. I suppose the data could be better, worse, or about the same. The fact of the matter is that HM leaders—and most of the rest of us—knew that transitions of care, under the hospitalist model, were a potential weakness. How many times have you heard Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, and John Nelson, MD, MHM, talk about the potential “voltage drop” with handoffs?

The good news is that leaders in our field have done something about this. Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) is a program SHM has helped implement at dozens of hospitals across the country to address the issue of unnecessary hospital readmissions (www.hospitalmedicine. org/boost). Improving transitions of care and preventing unnecessary readmissions should be on the minds of all hospitalists. If your program and your hospital have not yet taken steps to address this issue, please let this be your wake-up call.

Show Me the Money

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality. I agree with you that it is hard to look at costs without looking at quality. Therein lies the basis for our nation’s move toward value-based purchasing of healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011).

When I hear hospitalists explain why the role of hospitalists was developed, the explanation often involves some discussion of cost and LOS reduction. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not that I believe HM has focused too much attention on cost reduction. I believe we have not focused enough on improving quality. This should not be surprising. Moving the bar on cost reduction is a lot easier than moving the bar on quality and patient safety. The first step toward improvement is an understanding of what you are doing currently. If your hospitalist group has not implemented a program to help its hospitalists measure the quality of care being provided, again, this is your wake-up call.

Last, but not least, for those of you who are not “surprised” by the results because of the belief that hospitalists were created to help the hospital save money and nothing more, I could not disagree with you more. I look at the roles that hospitalists have taken on in our nation’s hospitals, and I am incredibly proud to call myself a hospitalist.

Hospitalists are providing timely care when patients need it. Hospitalists are caring for patients without PCPs. Not only do hospitalists allow PCPs to provide more care in their outpatient clinics, but hospitalists also are caring for patients in ICUs in many places where there are not enough doctors sufficiently trained in critical care.

Rather than acting as an indictment on HM, I believe the Annals article makes a comment on the misalignment of incentives in our healthcare system.

It is 2011, not 1996; HM is here to stay. Most acute-care hospitals in America could not function without hospitalists. I applaud Kuo and Goodwin for doing the research and publishing their results. Let this be an opportunity for hospitalists around the country to think about how to implement systems to improve transitions of care and the quality of care we provide.

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

Reference

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality.

I suspect most of you have reviewed the study or at least heard about it. Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, blogged about the study. An article about the study appeared in American Medical Association News. Even National Public Radio ran a piece about the study on their show “Morning Edition.”

I am, of course, referring to the study by Kuo and Goodwin, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in early August.1

In this study, the authors looked at a sample of patients (5%) with primary-care physicians (PCPs) enrolled in Medicare who were cared for by their PCP or a hospitalist during a period from 2001 to 2006. The authors stated their underlying hypotheses as:

- Hospitalist care would be associated with costs shifting from the hospital to the post-hospital setting;

- Hospitalist care would be associated with a decrease in discharges directly to home; and

- Discontinuities of care associated with hospitalist care would lead to a greater rate of visits to the emergency room and readmissions to the hospital, resulting in increased Medicare costs.

Did the authors say hospitalist care cost more? They can’t possibly be correct, can they? Don’t all the hospitalist studies show that hospitalists provide the same quality of care as primary-care doctors, except the costs are lower and the hospital length of stay (LOS) is shorter when hospitalists care for patients?

The point here is that these investigators look at the care not only during a patient’s hospital stay, but also for 30 days after discharge. This is something that had not been done previously—at least not on this scale.

Focus on Facts

And what did the authors find? Patients cared for by hospitalists, as compared to their PCPs, had a shorter LOS and lower in-hospital costs, but these patients also were less likely to be discharged directly to home, less likely to see their PCPs post-discharge, and had more hospital readmissions, ED visits, and nursing home visits after discharge.

Since its release two months ago, I have heard a lot of discussion about the study. Here are a few of the comments I’ve heard:

- “This was an observational study. You can’t possibly remove all confounders in an observational study.”

- “The authors looked at a time period early in the hospitalist movement. If they did the study today, the results would be different.”

- “The additional costs hospitalists incurred were only $50 per patient. Wouldn’t you pay $50 more if the care was better?”

- “This is why hospitals hired hospitalists. They save money for the hospitals. What did they expect to find?”

I agree that observational studies have limitations (even the authors acknowledged this), but this doesn’t mean results from observational studies are invalid. Some of us don’t want to hear this, but this actually was a pretty well-done study with a robust statistical analysis. We should recognize the study has limitations and think about the results.

Kuo and Goodwin looked at data during a period of time early in the hospitalist movement; the results could be different if the study were to be repeated today. But we don’t know what the data would be today. I suppose the data could be better, worse, or about the same. The fact of the matter is that HM leaders—and most of the rest of us—knew that transitions of care, under the hospitalist model, were a potential weakness. How many times have you heard Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, and John Nelson, MD, MHM, talk about the potential “voltage drop” with handoffs?

The good news is that leaders in our field have done something about this. Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safer Transitions) is a program SHM has helped implement at dozens of hospitals across the country to address the issue of unnecessary hospital readmissions (www.hospitalmedicine. org/boost). Improving transitions of care and preventing unnecessary readmissions should be on the minds of all hospitalists. If your program and your hospital have not yet taken steps to address this issue, please let this be your wake-up call.

Show Me the Money

For those who say they would pay $50 more per patient if the quality is better, here’s the problem: Show me the data that say hospitalist care is higher-quality. I agree with you that it is hard to look at costs without looking at quality. Therein lies the basis for our nation’s move toward value-based purchasing of healthcare (see “Value-Based Purchasing Raises the Stakes,” May 2011).

When I hear hospitalists explain why the role of hospitalists was developed, the explanation often involves some discussion of cost and LOS reduction. Don’t get me wrong; it’s not that I believe HM has focused too much attention on cost reduction. I believe we have not focused enough on improving quality. This should not be surprising. Moving the bar on cost reduction is a lot easier than moving the bar on quality and patient safety. The first step toward improvement is an understanding of what you are doing currently. If your hospitalist group has not implemented a program to help its hospitalists measure the quality of care being provided, again, this is your wake-up call.

Last, but not least, for those of you who are not “surprised” by the results because of the belief that hospitalists were created to help the hospital save money and nothing more, I could not disagree with you more. I look at the roles that hospitalists have taken on in our nation’s hospitals, and I am incredibly proud to call myself a hospitalist.

Hospitalists are providing timely care when patients need it. Hospitalists are caring for patients without PCPs. Not only do hospitalists allow PCPs to provide more care in their outpatient clinics, but hospitalists also are caring for patients in ICUs in many places where there are not enough doctors sufficiently trained in critical care.

Rather than acting as an indictment on HM, I believe the Annals article makes a comment on the misalignment of incentives in our healthcare system.

It is 2011, not 1996; HM is here to stay. Most acute-care hospitals in America could not function without hospitalists. I applaud Kuo and Goodwin for doing the research and publishing their results. Let this be an opportunity for hospitalists around the country to think about how to implement systems to improve transitions of care and the quality of care we provide.

Dr. Li is president of SHM.

Reference

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: A Discharge Solution—or Problem?

In a bit of counterintuition, an empty discharge lounge might be the most successful kind.

Christine Collins, executive director of patient access services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, says that the lounge should be a service for discharged patients who have completed medical treatment, but who for some reason remain unable to leave the institution. Such cases can include waiting on a prescription from the pharmacy, or simply waiting on a relative or friend to arrive with transportation.

—Christine Collins, executive director, patient access services, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

She does not view Brigham’s discharge lounge, a room with lounge chairs and light meals that is staffed by a registered nurse, as the answer to the throughput conundrum hospitals across the country face each and every day. So when the lounge is empty, it means patients have been discharged without any hang-ups.

“It’s not a patient-care area,” Collins says. “They’re people that should be home.”

Some view discharge lounges as a potential aid in smoothing out the discharge process. In theory, patients ready to be medically discharged but unable to leave the hospital have a place to go. But keeping the patients in the building, and under the eye of a nurse, could create liability issues, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, and a member of Team Hospitalist. Dr. Simone also wonders how the lounge concept impacts patient satisfaction, as some could view it negatively if they’re told they have to sit in what could be construed as a back-end waiting room.

“People need to assess what they’re doing it for and is it really accomplishing what they want it to accomplish,” Collins says.

Discharge lounges “can’t be another nursing unit because a patient is supposed to be discharged. ... Whether you have a discharge lounge or not, you need to improve your systems so that the patients leave when they leave.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

In a bit of counterintuition, an empty discharge lounge might be the most successful kind.

Christine Collins, executive director of patient access services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, says that the lounge should be a service for discharged patients who have completed medical treatment, but who for some reason remain unable to leave the institution. Such cases can include waiting on a prescription from the pharmacy, or simply waiting on a relative or friend to arrive with transportation.

—Christine Collins, executive director, patient access services, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

She does not view Brigham’s discharge lounge, a room with lounge chairs and light meals that is staffed by a registered nurse, as the answer to the throughput conundrum hospitals across the country face each and every day. So when the lounge is empty, it means patients have been discharged without any hang-ups.

“It’s not a patient-care area,” Collins says. “They’re people that should be home.”

Some view discharge lounges as a potential aid in smoothing out the discharge process. In theory, patients ready to be medically discharged but unable to leave the hospital have a place to go. But keeping the patients in the building, and under the eye of a nurse, could create liability issues, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, and a member of Team Hospitalist. Dr. Simone also wonders how the lounge concept impacts patient satisfaction, as some could view it negatively if they’re told they have to sit in what could be construed as a back-end waiting room.

“People need to assess what they’re doing it for and is it really accomplishing what they want it to accomplish,” Collins says.

Discharge lounges “can’t be another nursing unit because a patient is supposed to be discharged. ... Whether you have a discharge lounge or not, you need to improve your systems so that the patients leave when they leave.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

In a bit of counterintuition, an empty discharge lounge might be the most successful kind.

Christine Collins, executive director of patient access services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, says that the lounge should be a service for discharged patients who have completed medical treatment, but who for some reason remain unable to leave the institution. Such cases can include waiting on a prescription from the pharmacy, or simply waiting on a relative or friend to arrive with transportation.

—Christine Collins, executive director, patient access services, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

She does not view Brigham’s discharge lounge, a room with lounge chairs and light meals that is staffed by a registered nurse, as the answer to the throughput conundrum hospitals across the country face each and every day. So when the lounge is empty, it means patients have been discharged without any hang-ups.

“It’s not a patient-care area,” Collins says. “They’re people that should be home.”

Some view discharge lounges as a potential aid in smoothing out the discharge process. In theory, patients ready to be medically discharged but unable to leave the hospital have a place to go. But keeping the patients in the building, and under the eye of a nurse, could create liability issues, says Ken Simone, DO, SFHM, president of Hospitalist and Practice Solutions in Veazie, Maine, and a member of Team Hospitalist. Dr. Simone also wonders how the lounge concept impacts patient satisfaction, as some could view it negatively if they’re told they have to sit in what could be construed as a back-end waiting room.

“People need to assess what they’re doing it for and is it really accomplishing what they want it to accomplish,” Collins says.

Discharge lounges “can’t be another nursing unit because a patient is supposed to be discharged. ... Whether you have a discharge lounge or not, you need to improve your systems so that the patients leave when they leave.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Experts discuss strategies to improve early discharges

HM@15 - Are You Living Up to High Expectations of Efficiency?

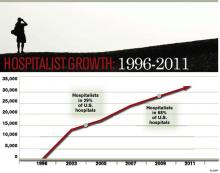

In 2002, a summary article in the Journal of the American Medical Association helped put the relatively small but rapidly growing HM profession on the map. Reviewing the available data, Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, and Lee Goldman, MD, MPH, of the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) concluded that implementing a hospitalist program yielded an average savings of 13.4% in hospital costs and a 16.6% reduction in the length of stay (LOS).1

A decade later, the idea of efficiency has become so intertwined with hospitalists that SHM has included the concept in its definition of a profession that now comprises more than 30,000 doctors, nurses, and other care providers. HM practitioners work to enhance hospital and healthcare performance, in part, through “efficient use of hospital and healthcare resources,” according to SHM.

The growth of any profession can create exceptions and outliers, and observers point out that HM programs have become as varied as the hospitals in which they reside, complicating any attempt at broad generalizations. As a core part of the job description, though, efficiency and its implied benefit on costs have been widely promoted as arguments for expanding HM’s reach.

So are hospitalists meeting the lofty expectations?

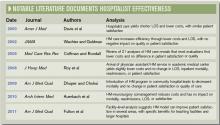

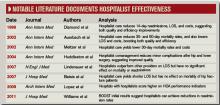

A Look at the Evidence

A large retrospective study that examined outcomes of care for nearly 77,000 patients in 45 hospitals found that those cared for by hospitalists had a “modestly shorter” stay (by 0.4 days) in the hospital than those cared for by either general internists or family physicians.2 Hospitalists saved about $270 per hospitalization compared with general internists but only about $125 per stay compared with family physicians, the latter of which was not deemed statistically significant.

A more recent review of 33 studies found general agreement that hospitalist care led to reduced costs and length of stay but revealed less uniformity in the impacts on quality and patient outcomes.3