User login

US docs call for single-payer health reform

Photo by Matthew Lester

A group of US physicians has called for the creation of a publicly financed, single-payer national health program that would cover all Americans for all medically necessary care.

The proposal, which was drafted by a panel of 39 physicians, was announced in an editorial published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The proposal currently has more than 2000 signatures from physicians practicing in 48 states and the District of Columbia.

“Our nation is at a crossroads,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist in Boston, Massachusetts, who is lead author of the editorial and co-chair of the working group that drafted the proposal.

“Despite the passage of the Affordable Care Act 6 years ago, 30 million Americans remain uninsured, an even greater number are underinsured, financial barriers to care like co-pays and deductibles are rising, bureaucracy is growing, provider networks are narrowing, and medical costs are continuing to climb.”

Dr Gaffney and his colleagues described their publicly financed, single-payer national health program (NHP) as follows.

Patients could choose to visit any doctor and hospital. Most hospitals and clinics would remain privately owned and operated, receiving a budget from the NHP to cover all operating costs. Physicians could continue to practice on a fee-for-service basis or receive salaries from group practices, hospitals, or clinics.

The program would be paid for by combining current sources of government health spending into a single fund with new taxes that would be fully offset by reductions in premiums and out-of-pocket spending. Co-pays and deductibles would be eliminated.

The single-payer program would save about $500 billion annually by eliminating the high overhead and profits of insurance firms and the paperwork they require from hospitals and doctors.

The administrative savings of the system would fully offset the costs of covering the uninsured and upgraded coverage for everyone else—eg, full coverage of prescription drugs, dental care, and long-term care. Savings would also be redirected to currently underfunded health priorities, particularly public health.

The “single payer” would be in a position to negotiate lower prices for medications and other medical supplies.

More details and documents related to the physicians’ proposal are available on the Physicians for a National Health Program website.

The Physicians for a National Health Program is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research and education organization founded in 1987. The organization had no role in funding the aforementioned proposal or editorial. ![]()

Photo by Matthew Lester

A group of US physicians has called for the creation of a publicly financed, single-payer national health program that would cover all Americans for all medically necessary care.

The proposal, which was drafted by a panel of 39 physicians, was announced in an editorial published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The proposal currently has more than 2000 signatures from physicians practicing in 48 states and the District of Columbia.

“Our nation is at a crossroads,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist in Boston, Massachusetts, who is lead author of the editorial and co-chair of the working group that drafted the proposal.

“Despite the passage of the Affordable Care Act 6 years ago, 30 million Americans remain uninsured, an even greater number are underinsured, financial barriers to care like co-pays and deductibles are rising, bureaucracy is growing, provider networks are narrowing, and medical costs are continuing to climb.”

Dr Gaffney and his colleagues described their publicly financed, single-payer national health program (NHP) as follows.

Patients could choose to visit any doctor and hospital. Most hospitals and clinics would remain privately owned and operated, receiving a budget from the NHP to cover all operating costs. Physicians could continue to practice on a fee-for-service basis or receive salaries from group practices, hospitals, or clinics.

The program would be paid for by combining current sources of government health spending into a single fund with new taxes that would be fully offset by reductions in premiums and out-of-pocket spending. Co-pays and deductibles would be eliminated.

The single-payer program would save about $500 billion annually by eliminating the high overhead and profits of insurance firms and the paperwork they require from hospitals and doctors.

The administrative savings of the system would fully offset the costs of covering the uninsured and upgraded coverage for everyone else—eg, full coverage of prescription drugs, dental care, and long-term care. Savings would also be redirected to currently underfunded health priorities, particularly public health.

The “single payer” would be in a position to negotiate lower prices for medications and other medical supplies.

More details and documents related to the physicians’ proposal are available on the Physicians for a National Health Program website.

The Physicians for a National Health Program is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research and education organization founded in 1987. The organization had no role in funding the aforementioned proposal or editorial. ![]()

Photo by Matthew Lester

A group of US physicians has called for the creation of a publicly financed, single-payer national health program that would cover all Americans for all medically necessary care.

The proposal, which was drafted by a panel of 39 physicians, was announced in an editorial published in the American Journal of Public Health.

The proposal currently has more than 2000 signatures from physicians practicing in 48 states and the District of Columbia.

“Our nation is at a crossroads,” said Adam Gaffney, MD, a pulmonary disease and critical care specialist in Boston, Massachusetts, who is lead author of the editorial and co-chair of the working group that drafted the proposal.

“Despite the passage of the Affordable Care Act 6 years ago, 30 million Americans remain uninsured, an even greater number are underinsured, financial barriers to care like co-pays and deductibles are rising, bureaucracy is growing, provider networks are narrowing, and medical costs are continuing to climb.”

Dr Gaffney and his colleagues described their publicly financed, single-payer national health program (NHP) as follows.

Patients could choose to visit any doctor and hospital. Most hospitals and clinics would remain privately owned and operated, receiving a budget from the NHP to cover all operating costs. Physicians could continue to practice on a fee-for-service basis or receive salaries from group practices, hospitals, or clinics.

The program would be paid for by combining current sources of government health spending into a single fund with new taxes that would be fully offset by reductions in premiums and out-of-pocket spending. Co-pays and deductibles would be eliminated.

The single-payer program would save about $500 billion annually by eliminating the high overhead and profits of insurance firms and the paperwork they require from hospitals and doctors.

The administrative savings of the system would fully offset the costs of covering the uninsured and upgraded coverage for everyone else—eg, full coverage of prescription drugs, dental care, and long-term care. Savings would also be redirected to currently underfunded health priorities, particularly public health.

The “single payer” would be in a position to negotiate lower prices for medications and other medical supplies.

More details and documents related to the physicians’ proposal are available on the Physicians for a National Health Program website.

The Physicians for a National Health Program is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research and education organization founded in 1987. The organization had no role in funding the aforementioned proposal or editorial. ![]()

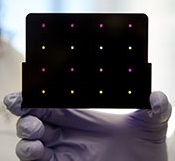

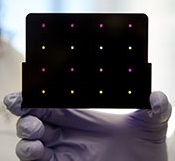

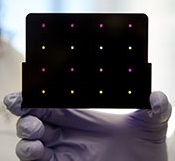

A new paper-based test for the Zika virus

based test for Zika virus.

Purple dots indicate samples

infected with Zika, and yellow

dots indicate Zika-free samples.

Photo courtesy of the Wyss

Institute at Harvard University

A new paper-based test can diagnose Zika virus infection within a few hours, according to research published in Cell.

The test is based on technology previously developed to detect the Ebola virus.

In October 2014, researchers demonstrated that they could create synthetic gene networks and embed them on small discs of paper.

These gene networks can be programmed to detect a particular genetic sequence, which causes the paper to change color.

Upon learning about the Zika outbreak, the researchers decided to try adapting this technology to diagnose Zika.

“In a small number of weeks, we developed and validated a relatively rapid, inexpensive Zika diagnostic platform,” said study author James Collins, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Dr Collins and his colleagues developed sensors, embedded in the paper discs, that can detect 24 different RNA sequences found in the Zika viral genome. When the target RNA sequence is present, it initiates a series of interactions that turns the paper from yellow to purple.

This color change can be seen with the naked eye, but the researchers also developed an electronic reader that makes it easier to quantify the change, especially in cases where the sensor is detecting more than one RNA sequence.

All of the cellular components necessary for this process—including proteins, nucleic acids, and ribosomes—can be extracted from living cells and freeze-dried onto paper.

These paper discs can be stored at room temperature, making it easy to ship them to any location. Once rehydrated, all of the components function just as they would inside a living cell.

The researchers also incorporated a step that boosts the amount of viral RNA in the blood sample before exposing it to the sensor, using a system called nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA). This amplification step, which takes 1 to 2 hours, increases the test’s sensitivity 1 million-fold.

The team tested this diagnostic platform using synthesized RNA sequences corresponding to the Zika genome, which were then added to human blood serum.

They found the test could detect very low viral RNA concentrations in those samples and could also distinguish Zika from dengue.

The researchers then tested samples taken from monkeys infected with the Zika virus. (Samples from humans affected by the current Zika outbreak were too difficult to obtain.)

The team found that, in these samples, the test could detect viral RNA concentrations as low as 2 or 3 parts per quadrillion.

The researchers believe this approach could also be adapted to other viruses that may emerge in the future. Dr Collins hopes to team up with other scientists to further develop the technology for diagnosing Zika.

“Here, we’ve done a nice proof-of-principle demonstration, but more work and additional testing would be needed to ensure safety and efficacy before actual deployment,” he said. “We’re not far off.” ![]()

based test for Zika virus.

Purple dots indicate samples

infected with Zika, and yellow

dots indicate Zika-free samples.

Photo courtesy of the Wyss

Institute at Harvard University

A new paper-based test can diagnose Zika virus infection within a few hours, according to research published in Cell.

The test is based on technology previously developed to detect the Ebola virus.

In October 2014, researchers demonstrated that they could create synthetic gene networks and embed them on small discs of paper.

These gene networks can be programmed to detect a particular genetic sequence, which causes the paper to change color.

Upon learning about the Zika outbreak, the researchers decided to try adapting this technology to diagnose Zika.

“In a small number of weeks, we developed and validated a relatively rapid, inexpensive Zika diagnostic platform,” said study author James Collins, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Dr Collins and his colleagues developed sensors, embedded in the paper discs, that can detect 24 different RNA sequences found in the Zika viral genome. When the target RNA sequence is present, it initiates a series of interactions that turns the paper from yellow to purple.

This color change can be seen with the naked eye, but the researchers also developed an electronic reader that makes it easier to quantify the change, especially in cases where the sensor is detecting more than one RNA sequence.

All of the cellular components necessary for this process—including proteins, nucleic acids, and ribosomes—can be extracted from living cells and freeze-dried onto paper.

These paper discs can be stored at room temperature, making it easy to ship them to any location. Once rehydrated, all of the components function just as they would inside a living cell.

The researchers also incorporated a step that boosts the amount of viral RNA in the blood sample before exposing it to the sensor, using a system called nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA). This amplification step, which takes 1 to 2 hours, increases the test’s sensitivity 1 million-fold.

The team tested this diagnostic platform using synthesized RNA sequences corresponding to the Zika genome, which were then added to human blood serum.

They found the test could detect very low viral RNA concentrations in those samples and could also distinguish Zika from dengue.

The researchers then tested samples taken from monkeys infected with the Zika virus. (Samples from humans affected by the current Zika outbreak were too difficult to obtain.)

The team found that, in these samples, the test could detect viral RNA concentrations as low as 2 or 3 parts per quadrillion.

The researchers believe this approach could also be adapted to other viruses that may emerge in the future. Dr Collins hopes to team up with other scientists to further develop the technology for diagnosing Zika.

“Here, we’ve done a nice proof-of-principle demonstration, but more work and additional testing would be needed to ensure safety and efficacy before actual deployment,” he said. “We’re not far off.” ![]()

based test for Zika virus.

Purple dots indicate samples

infected with Zika, and yellow

dots indicate Zika-free samples.

Photo courtesy of the Wyss

Institute at Harvard University

A new paper-based test can diagnose Zika virus infection within a few hours, according to research published in Cell.

The test is based on technology previously developed to detect the Ebola virus.

In October 2014, researchers demonstrated that they could create synthetic gene networks and embed them on small discs of paper.

These gene networks can be programmed to detect a particular genetic sequence, which causes the paper to change color.

Upon learning about the Zika outbreak, the researchers decided to try adapting this technology to diagnose Zika.

“In a small number of weeks, we developed and validated a relatively rapid, inexpensive Zika diagnostic platform,” said study author James Collins, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

Dr Collins and his colleagues developed sensors, embedded in the paper discs, that can detect 24 different RNA sequences found in the Zika viral genome. When the target RNA sequence is present, it initiates a series of interactions that turns the paper from yellow to purple.

This color change can be seen with the naked eye, but the researchers also developed an electronic reader that makes it easier to quantify the change, especially in cases where the sensor is detecting more than one RNA sequence.

All of the cellular components necessary for this process—including proteins, nucleic acids, and ribosomes—can be extracted from living cells and freeze-dried onto paper.

These paper discs can be stored at room temperature, making it easy to ship them to any location. Once rehydrated, all of the components function just as they would inside a living cell.

The researchers also incorporated a step that boosts the amount of viral RNA in the blood sample before exposing it to the sensor, using a system called nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA). This amplification step, which takes 1 to 2 hours, increases the test’s sensitivity 1 million-fold.

The team tested this diagnostic platform using synthesized RNA sequences corresponding to the Zika genome, which were then added to human blood serum.

They found the test could detect very low viral RNA concentrations in those samples and could also distinguish Zika from dengue.

The researchers then tested samples taken from monkeys infected with the Zika virus. (Samples from humans affected by the current Zika outbreak were too difficult to obtain.)

The team found that, in these samples, the test could detect viral RNA concentrations as low as 2 or 3 parts per quadrillion.

The researchers believe this approach could also be adapted to other viruses that may emerge in the future. Dr Collins hopes to team up with other scientists to further develop the technology for diagnosing Zika.

“Here, we’ve done a nice proof-of-principle demonstration, but more work and additional testing would be needed to ensure safety and efficacy before actual deployment,” he said. “We’re not far off.” ![]()

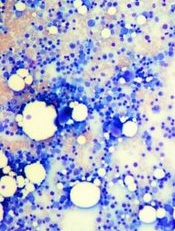

Team creates bone marrow on a chip

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic chip device mimics living bone marrow, according to research published in Tissue Engineering.

Experiments showed the engineered bone marrow responded in a way similar to living bone marrow when exposed to damaging radiation followed by treatment with compounds that aid in blood cell recovery.

The researchers said this new bone marrow-on-a-chip device holds promise for testing and developing improved radiation countermeasures.

Yu-suke Torisawa, PhD, of Kyoto University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team used a tissue engineering approach to induce formation of new marrow-containing bone in mice. They then surgically removed the bone, placed it in a microfluidic device, and continuously perfused it with medium in vitro.

Next, the researchers set out to determine if the device would keep the engineered bone marrow alive so they could perform tests on it.

To test the system, the team analyzed the dynamics of blood cell production and evaluated the radiation-protecting effects of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein (BPI).

Experiments showed the microfluidic device could maintain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in normal proportions for at least 2 weeks in culture.

Over time, the researchers observed increases in the number of leukocytes and red blood cells in the microfluidic circulation. And they found that adding erythropoietin induced a significant increase in erythrocyte production.

When the researchers exposed the engineered bone marrow to gamma radiation, they saw reduced leukocyte production.

And when they treated the engineered bone marrow with G-CSF or BPI, the team saw significant increases in the number of hematopoietic stem cells and myeloid cells in the fluidic outflow.

On the other hand, BPI did not have such an effect on static bone marrow cultures. But the researchers pointed out that previous work has shown BPI can accelerate recovery from radiation-induced toxicity in vivo.

The team therefore concluded that, unlike static bone marrow cultures, engineered bone marrow grown in a microfluidic device effectively mimics the recovery response of bone marrow in the body. ![]()

Transparency doesn’t lower healthcare spending

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

Photo by Petr Kratochvil

Providing patients with a tool that enabled them to search for healthcare prices did not decrease their spending, according to a study published in JAMA.

Researchers studied the Truven Health Analytics Treatment Cost Calculator, an online price transparency tool that tells users how much they would pay out of pocket for services such as X-rays, lab tests, outpatient surgeries, or physician office visits at different sites.

The out-of-pocket cost estimates are based on the users’ health plan benefits and on how much they have already spent on healthcare during the year.

Two large national companies offered this tool to their employees in 2011 and 2012.

The researchers compared the healthcare spending patterns of employees (n=148,655) at these companies in the year before and after the tool was introduced with patterns among employees (n=295,983) of other companies that did not offer the tool.

Overall, having access to the tool was not associated with a reduction in outpatient spending, and subjects did not switch from more expensive outpatient hospital-based care to lower-cost settings.

The average outpatient spending among employees offered the tool was $2021 in the year before the tool was introduced and $2233 in the year after. Among control subjects, average outpatient spending increased from $1985 to $2138.

The average outpatient out-of-pocket spending among employees offered the tool was $507 in the year before it was introduced and $555 in the year after. In the control group, the average outpatient out-of-pocket spending increased from $490 to $520.

After the researchers adjusted for demographic and health characteristics, being offered the tool was associated with an average $59 increase in outpatient spending and an average $18 increase in out-of-pocket spending.

When the researchers looked only at patients with higher deductibles—who would be expected to have greater price-shopping incentives—they also found no evidence of reduction in spending.

“Despite large variation in healthcare prices, prevalence of high-deductible health plans, and widespread interest in price transparency, we did not find evidence that offering price transparency to employees generated savings,” said study author Sunita Desai, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

A possible explanation for this finding is that most patients did not actually use the tool. Only 10% of the employees who were offered the tool used it at least once in the first 12 months.

When patients did use the tool, more than half the searches were for relatively expensive services of over $1000.

“For expensive care that exceeds their deductible, patients may not see any reason to switch,” said study author Ateev Mehrotra, MD, also of Harvard Medical School. “They do not save by choosing a lower-cost provider, even if the health plan does.”

Still, the researchers said the tool does provide patients with valuable information, including their expected out-of-pocket costs, their deductible, and their health plan’s provider network.

“People might use the tools more—and focus more on choosing lower-priced care options—if they are combined with additional health plan benefit features that give greater incentive to price shop,” Dr Desai said. ![]()

Medical errors among leading causes of death in US

while another looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

In recent years, medical errors may have become one of the top causes of death in the US, according to a study published in The BMJ.

Investigators analyzed medical death rate data over an 8-year period and calculated that more than 250,000 deaths per year may be due to medical error.

That figure surpasses the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) third leading cause of death—respiratory disease, which kills close to 150,000 people per year.

The investigators said the CDC’s way of collecting national health statistics fails to classify medical errors separately on the death certificate. So the team is advocating for updated criteria for classifying deaths.

“Incidence rates for deaths directly attributable to medical care gone awry haven’t been recognized in any standardized method for collecting national statistics,” said study author Martin Makary, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The medical coding system was designed to maximize billing for physician services, not to collect national health statistics, as it is currently being used.”

Dr Makary noted that, in 1949, the US adopted an international form that used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) billing codes to tally causes of death.

“At that time, it was under-recognized that diagnostic errors, medical mistakes, and the absence of safety nets could result in someone’s death, and because of that, medical errors were unintentionally excluded from national health statistics,” Dr Makary said.

He pointed out that, since that time, national mortality statistics have been tabulated using billing codes, which don’t have a built-in way to recognize incidence rates of mortality due to medical care gone wrong.

For the current study, Dr Makary and Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins, examined 4 separate studies that analyzed medical death rate data from 2000 to 2008.

Then, using hospital admission rates from 2013, the investigators extrapolated that, based on a total of 35,416,020 hospitalizations, 251,454 deaths stemmed from medical error. This translates to 9.5% of all deaths each year in the US.

According to the CDC, in 2013, 611,105 people died of heart disease, 584,881 died of cancer, and 149,205 died of chronic respiratory disease.

These were the top 3 causes of death in the US. The newly calculated figure for medical errors puts this cause of death behind cancer but ahead of respiratory disease.

“Top-ranked causes of death as reported by the CDC inform our country’s research funding and public health priorities,” Dr Makary said. “Right now, cancer and heart disease get a ton of attention, but since medical errors don’t appear on the list, the problem doesn’t get the funding and attention it deserves.”

The investigators said most medical errors aren’t due to inherently bad doctors, and reporting these errors shouldn’t be addressed by punishment or legal action.

Rather, the pair believes that most errors represent systemic problems, including poorly coordinated care, fragmented insurance networks, the absence or underuse of safety nets, and other protocols, in addition to unwarranted variation in physician practice patterns that lack accountability.

“Unwarranted variation is endemic in healthcare,” Dr Makary said. “Developing consensus protocols that streamline the delivery of medicine and reduce variability can improve quality and lower costs in healthcare. More research on preventing medical errors from occurring is needed to address the problem.” ![]()

while another looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

In recent years, medical errors may have become one of the top causes of death in the US, according to a study published in The BMJ.

Investigators analyzed medical death rate data over an 8-year period and calculated that more than 250,000 deaths per year may be due to medical error.

That figure surpasses the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) third leading cause of death—respiratory disease, which kills close to 150,000 people per year.

The investigators said the CDC’s way of collecting national health statistics fails to classify medical errors separately on the death certificate. So the team is advocating for updated criteria for classifying deaths.

“Incidence rates for deaths directly attributable to medical care gone awry haven’t been recognized in any standardized method for collecting national statistics,” said study author Martin Makary, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The medical coding system was designed to maximize billing for physician services, not to collect national health statistics, as it is currently being used.”

Dr Makary noted that, in 1949, the US adopted an international form that used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) billing codes to tally causes of death.

“At that time, it was under-recognized that diagnostic errors, medical mistakes, and the absence of safety nets could result in someone’s death, and because of that, medical errors were unintentionally excluded from national health statistics,” Dr Makary said.

He pointed out that, since that time, national mortality statistics have been tabulated using billing codes, which don’t have a built-in way to recognize incidence rates of mortality due to medical care gone wrong.

For the current study, Dr Makary and Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins, examined 4 separate studies that analyzed medical death rate data from 2000 to 2008.

Then, using hospital admission rates from 2013, the investigators extrapolated that, based on a total of 35,416,020 hospitalizations, 251,454 deaths stemmed from medical error. This translates to 9.5% of all deaths each year in the US.

According to the CDC, in 2013, 611,105 people died of heart disease, 584,881 died of cancer, and 149,205 died of chronic respiratory disease.

These were the top 3 causes of death in the US. The newly calculated figure for medical errors puts this cause of death behind cancer but ahead of respiratory disease.

“Top-ranked causes of death as reported by the CDC inform our country’s research funding and public health priorities,” Dr Makary said. “Right now, cancer and heart disease get a ton of attention, but since medical errors don’t appear on the list, the problem doesn’t get the funding and attention it deserves.”

The investigators said most medical errors aren’t due to inherently bad doctors, and reporting these errors shouldn’t be addressed by punishment or legal action.

Rather, the pair believes that most errors represent systemic problems, including poorly coordinated care, fragmented insurance networks, the absence or underuse of safety nets, and other protocols, in addition to unwarranted variation in physician practice patterns that lack accountability.

“Unwarranted variation is endemic in healthcare,” Dr Makary said. “Developing consensus protocols that streamline the delivery of medicine and reduce variability can improve quality and lower costs in healthcare. More research on preventing medical errors from occurring is needed to address the problem.” ![]()

while another looks on

Photo courtesy of NCI

In recent years, medical errors may have become one of the top causes of death in the US, according to a study published in The BMJ.

Investigators analyzed medical death rate data over an 8-year period and calculated that more than 250,000 deaths per year may be due to medical error.

That figure surpasses the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) third leading cause of death—respiratory disease, which kills close to 150,000 people per year.

The investigators said the CDC’s way of collecting national health statistics fails to classify medical errors separately on the death certificate. So the team is advocating for updated criteria for classifying deaths.

“Incidence rates for deaths directly attributable to medical care gone awry haven’t been recognized in any standardized method for collecting national statistics,” said study author Martin Makary, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The medical coding system was designed to maximize billing for physician services, not to collect national health statistics, as it is currently being used.”

Dr Makary noted that, in 1949, the US adopted an international form that used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) billing codes to tally causes of death.

“At that time, it was under-recognized that diagnostic errors, medical mistakes, and the absence of safety nets could result in someone’s death, and because of that, medical errors were unintentionally excluded from national health statistics,” Dr Makary said.

He pointed out that, since that time, national mortality statistics have been tabulated using billing codes, which don’t have a built-in way to recognize incidence rates of mortality due to medical care gone wrong.

For the current study, Dr Makary and Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins, examined 4 separate studies that analyzed medical death rate data from 2000 to 2008.

Then, using hospital admission rates from 2013, the investigators extrapolated that, based on a total of 35,416,020 hospitalizations, 251,454 deaths stemmed from medical error. This translates to 9.5% of all deaths each year in the US.

According to the CDC, in 2013, 611,105 people died of heart disease, 584,881 died of cancer, and 149,205 died of chronic respiratory disease.

These were the top 3 causes of death in the US. The newly calculated figure for medical errors puts this cause of death behind cancer but ahead of respiratory disease.

“Top-ranked causes of death as reported by the CDC inform our country’s research funding and public health priorities,” Dr Makary said. “Right now, cancer and heart disease get a ton of attention, but since medical errors don’t appear on the list, the problem doesn’t get the funding and attention it deserves.”

The investigators said most medical errors aren’t due to inherently bad doctors, and reporting these errors shouldn’t be addressed by punishment or legal action.

Rather, the pair believes that most errors represent systemic problems, including poorly coordinated care, fragmented insurance networks, the absence or underuse of safety nets, and other protocols, in addition to unwarranted variation in physician practice patterns that lack accountability.

“Unwarranted variation is endemic in healthcare,” Dr Makary said. “Developing consensus protocols that streamline the delivery of medicine and reduce variability can improve quality and lower costs in healthcare. More research on preventing medical errors from occurring is needed to address the problem.” ![]()

Pre-treatment gut bacteria may predict risk of BSI

A new study suggests the composition of a cancer patient’s intestinal microbiome before treatment may predict his risk of developing a bloodstream infection (BSI) after treatment.

Researchers analyzed fecal samples from patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who were set to receive an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning.

The team found that patients with less diversity in their fecal samples before this treatment were more likely to develop a BSI after.

Emmanuel Montassier, MD, PhD, of Nantes University Hospital in France, and his colleagues conducted this study and reported the result in Genome Medicine.

A previous study suggested that intestinal domination—when a single bacterial taxon occupies at least 30% of the microbiota—is associated with BSIs in patients undergoing allo-HSCT. However, the role of the intestinal microbiome before treatment was not clear.

So Dr Montassier and his colleagues set out to characterize the fecal microbiome before treatment. To do this, they sequenced the bacterial DNA of fecal samples from 28 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The team collected the samples before patients began a 5-day myeloablative conditioning regimen (high-dose carmustine, etoposide, aracytine, and melphalan), followed by allo-HSCT on the seventh day.

Eleven of these patients developed a BSI at a mean of 12 days after sample collection. Two patients (18.2%) developed Enterococcus BSI, 4 (36.4%) developed Escherichia coli BSI, and 5 (45.5%) developed other Gammaproteobacteria BSI.

The researchers said that alpha diversity in samples from these patients was significantly lower than alpha diversity from patients who did not develop a BSI, with reduced evenness (Shannon index, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.004) and reduced richness (Observed species, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.001)

The team also noted that, compared to patients who did not develop a BSI, those who did had decreased abundance of Barnesiellaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Faecalibacterium, Christensenella, Dehalobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Sutterella.

Using this information, the researchers developed a BSI risk index that could predict the likelihood of a BSI with 90% sensitivity and specificity.

“This method worked even better than we expected because we found a consistent difference between the gut bacteria in those who developed infections and those who did not,” said study author Dan Knights, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This research is an early demonstration that we may be able to use the bugs in our gut to predict infections and possibly develop new prognostic models in other diseases.”

Still, the researchers said these findings are based on a limited number of patients treated with the same regimen at a single clinic. So the next step for this research is to validate the findings in a much larger cohort including patients with different cancer types, different treatment types, and from multiple treatment centers.

“We still need to determine if these bacteria are playing any kind of causal role in the infections or if they are simply acting as biomarkers for some other predisposing condition in the patient,” Dr Montassier said. ![]()

A new study suggests the composition of a cancer patient’s intestinal microbiome before treatment may predict his risk of developing a bloodstream infection (BSI) after treatment.

Researchers analyzed fecal samples from patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who were set to receive an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning.

The team found that patients with less diversity in their fecal samples before this treatment were more likely to develop a BSI after.

Emmanuel Montassier, MD, PhD, of Nantes University Hospital in France, and his colleagues conducted this study and reported the result in Genome Medicine.

A previous study suggested that intestinal domination—when a single bacterial taxon occupies at least 30% of the microbiota—is associated with BSIs in patients undergoing allo-HSCT. However, the role of the intestinal microbiome before treatment was not clear.

So Dr Montassier and his colleagues set out to characterize the fecal microbiome before treatment. To do this, they sequenced the bacterial DNA of fecal samples from 28 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The team collected the samples before patients began a 5-day myeloablative conditioning regimen (high-dose carmustine, etoposide, aracytine, and melphalan), followed by allo-HSCT on the seventh day.

Eleven of these patients developed a BSI at a mean of 12 days after sample collection. Two patients (18.2%) developed Enterococcus BSI, 4 (36.4%) developed Escherichia coli BSI, and 5 (45.5%) developed other Gammaproteobacteria BSI.

The researchers said that alpha diversity in samples from these patients was significantly lower than alpha diversity from patients who did not develop a BSI, with reduced evenness (Shannon index, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.004) and reduced richness (Observed species, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.001)

The team also noted that, compared to patients who did not develop a BSI, those who did had decreased abundance of Barnesiellaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Faecalibacterium, Christensenella, Dehalobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Sutterella.

Using this information, the researchers developed a BSI risk index that could predict the likelihood of a BSI with 90% sensitivity and specificity.

“This method worked even better than we expected because we found a consistent difference between the gut bacteria in those who developed infections and those who did not,” said study author Dan Knights, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This research is an early demonstration that we may be able to use the bugs in our gut to predict infections and possibly develop new prognostic models in other diseases.”

Still, the researchers said these findings are based on a limited number of patients treated with the same regimen at a single clinic. So the next step for this research is to validate the findings in a much larger cohort including patients with different cancer types, different treatment types, and from multiple treatment centers.

“We still need to determine if these bacteria are playing any kind of causal role in the infections or if they are simply acting as biomarkers for some other predisposing condition in the patient,” Dr Montassier said. ![]()

A new study suggests the composition of a cancer patient’s intestinal microbiome before treatment may predict his risk of developing a bloodstream infection (BSI) after treatment.

Researchers analyzed fecal samples from patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who were set to receive an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) with myeloablative conditioning.

The team found that patients with less diversity in their fecal samples before this treatment were more likely to develop a BSI after.

Emmanuel Montassier, MD, PhD, of Nantes University Hospital in France, and his colleagues conducted this study and reported the result in Genome Medicine.

A previous study suggested that intestinal domination—when a single bacterial taxon occupies at least 30% of the microbiota—is associated with BSIs in patients undergoing allo-HSCT. However, the role of the intestinal microbiome before treatment was not clear.

So Dr Montassier and his colleagues set out to characterize the fecal microbiome before treatment. To do this, they sequenced the bacterial DNA of fecal samples from 28 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The team collected the samples before patients began a 5-day myeloablative conditioning regimen (high-dose carmustine, etoposide, aracytine, and melphalan), followed by allo-HSCT on the seventh day.

Eleven of these patients developed a BSI at a mean of 12 days after sample collection. Two patients (18.2%) developed Enterococcus BSI, 4 (36.4%) developed Escherichia coli BSI, and 5 (45.5%) developed other Gammaproteobacteria BSI.

The researchers said that alpha diversity in samples from these patients was significantly lower than alpha diversity from patients who did not develop a BSI, with reduced evenness (Shannon index, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.004) and reduced richness (Observed species, Monte Carlo permuted t-test two-sided P value = 0.001)

The team also noted that, compared to patients who did not develop a BSI, those who did had decreased abundance of Barnesiellaceae, Coriobacteriaceae, Faecalibacterium, Christensenella, Dehalobacterium, Desulfovibrio, and Sutterella.

Using this information, the researchers developed a BSI risk index that could predict the likelihood of a BSI with 90% sensitivity and specificity.

“This method worked even better than we expected because we found a consistent difference between the gut bacteria in those who developed infections and those who did not,” said study author Dan Knights, PhD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“This research is an early demonstration that we may be able to use the bugs in our gut to predict infections and possibly develop new prognostic models in other diseases.”

Still, the researchers said these findings are based on a limited number of patients treated with the same regimen at a single clinic. So the next step for this research is to validate the findings in a much larger cohort including patients with different cancer types, different treatment types, and from multiple treatment centers.

“We still need to determine if these bacteria are playing any kind of causal role in the infections or if they are simply acting as biomarkers for some other predisposing condition in the patient,” Dr Montassier said. ![]()

Current cancer drug discovery method flawed, team says

Image courtesy of PNAS

The primary method used to test compounds for anticancer activity in vitro may produce inaccurate results, according to researchers.

Therefore, they have developed a new metric to evaluate a compound’s effect on cell proliferation—the drug-induced proliferation (DIP) rate.

They believe this metric, described in Nature Methods, overcomes the time-dependent bias of traditional proliferation assays.

“More than 90% of candidate cancer drugs fail in late-stage clinical trials, costing hundreds of millions of dollars,” said study author Vito Quaranta, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

“The flawed in vitro drug discovery metric may not be the only responsible factor, but it may be worth pursuing an estimate of its impact.”

For more than 30 years, scientists have evaluated the ability of a compound to kill cells by adding the compound and counting how many cells are alive after 72 hours.

However, these proliferation assays, which measure cell number at a single time point, don’t take into account the bias introduced by exponential cell proliferation, even in the presence of the drug, said study author Darren Tyson, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“Cells are not uniform,” added Dr Quaranta. “They all proliferate exponentially but at different rates. At 72 hours, some cells will have doubled 3 times, and others will not have doubled at all.”

In addition, he noted, drugs don’t all behave the same way on every cell line. For example, a drug might have an immediate effect on one cell line and a delayed effect on another.

Therefore, he and his colleagues used a systems biology approach to demonstrate the time-dependent bias in static proliferation assays and to develop the time-independent DIP rate metric.

The researchers evaluated the responses of 4 different melanoma cell lines to the drug vemurafenib, currently used to treat melanoma, with the standard metric and with the DIP rate.

In one cell line, the team found a stark disagreement between the two metrics.

“The static metric says that the cell line is very sensitive to vemurafenib,” said Leonard Harris, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“However, our analysis shows this is not the case. A brief period of drug sensitivity, quickly followed by rebound, fools the static metric but not the DIP rate.”

The findings “suggest we should expect melanoma tumors treated with this drug to come back, and that’s what has happened, puzzling investigators,” Dr Quaranta said. “DIP rate analyses may help solve this conundrum, leading to better treatment strategies.”

These findings have particular importance in light of recent international efforts to generate data sets that include the responses of “thousands of cell lines to hundreds of compounds,” Dr Quaranta said.

The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) databases include drug response data along with genomic and proteomic data that detail each cell line’s molecular makeup.

“The idea is to look for statistical correlations—these particular cell lines with this particular makeup are sensitive to these types of compounds—to use these large databases as discovery tools for new therapeutic targets in cancer,” Dr Quaranta said. “If the metric by which you’ve evaluated the drug sensitivity of the cells is wrong, your statistical correlations are basically no good.” ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

The primary method used to test compounds for anticancer activity in vitro may produce inaccurate results, according to researchers.

Therefore, they have developed a new metric to evaluate a compound’s effect on cell proliferation—the drug-induced proliferation (DIP) rate.

They believe this metric, described in Nature Methods, overcomes the time-dependent bias of traditional proliferation assays.

“More than 90% of candidate cancer drugs fail in late-stage clinical trials, costing hundreds of millions of dollars,” said study author Vito Quaranta, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

“The flawed in vitro drug discovery metric may not be the only responsible factor, but it may be worth pursuing an estimate of its impact.”

For more than 30 years, scientists have evaluated the ability of a compound to kill cells by adding the compound and counting how many cells are alive after 72 hours.

However, these proliferation assays, which measure cell number at a single time point, don’t take into account the bias introduced by exponential cell proliferation, even in the presence of the drug, said study author Darren Tyson, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“Cells are not uniform,” added Dr Quaranta. “They all proliferate exponentially but at different rates. At 72 hours, some cells will have doubled 3 times, and others will not have doubled at all.”

In addition, he noted, drugs don’t all behave the same way on every cell line. For example, a drug might have an immediate effect on one cell line and a delayed effect on another.

Therefore, he and his colleagues used a systems biology approach to demonstrate the time-dependent bias in static proliferation assays and to develop the time-independent DIP rate metric.

The researchers evaluated the responses of 4 different melanoma cell lines to the drug vemurafenib, currently used to treat melanoma, with the standard metric and with the DIP rate.

In one cell line, the team found a stark disagreement between the two metrics.

“The static metric says that the cell line is very sensitive to vemurafenib,” said Leonard Harris, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“However, our analysis shows this is not the case. A brief period of drug sensitivity, quickly followed by rebound, fools the static metric but not the DIP rate.”

The findings “suggest we should expect melanoma tumors treated with this drug to come back, and that’s what has happened, puzzling investigators,” Dr Quaranta said. “DIP rate analyses may help solve this conundrum, leading to better treatment strategies.”

These findings have particular importance in light of recent international efforts to generate data sets that include the responses of “thousands of cell lines to hundreds of compounds,” Dr Quaranta said.

The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) databases include drug response data along with genomic and proteomic data that detail each cell line’s molecular makeup.

“The idea is to look for statistical correlations—these particular cell lines with this particular makeup are sensitive to these types of compounds—to use these large databases as discovery tools for new therapeutic targets in cancer,” Dr Quaranta said. “If the metric by which you’ve evaluated the drug sensitivity of the cells is wrong, your statistical correlations are basically no good.” ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

The primary method used to test compounds for anticancer activity in vitro may produce inaccurate results, according to researchers.

Therefore, they have developed a new metric to evaluate a compound’s effect on cell proliferation—the drug-induced proliferation (DIP) rate.

They believe this metric, described in Nature Methods, overcomes the time-dependent bias of traditional proliferation assays.

“More than 90% of candidate cancer drugs fail in late-stage clinical trials, costing hundreds of millions of dollars,” said study author Vito Quaranta, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

“The flawed in vitro drug discovery metric may not be the only responsible factor, but it may be worth pursuing an estimate of its impact.”

For more than 30 years, scientists have evaluated the ability of a compound to kill cells by adding the compound and counting how many cells are alive after 72 hours.

However, these proliferation assays, which measure cell number at a single time point, don’t take into account the bias introduced by exponential cell proliferation, even in the presence of the drug, said study author Darren Tyson, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“Cells are not uniform,” added Dr Quaranta. “They all proliferate exponentially but at different rates. At 72 hours, some cells will have doubled 3 times, and others will not have doubled at all.”

In addition, he noted, drugs don’t all behave the same way on every cell line. For example, a drug might have an immediate effect on one cell line and a delayed effect on another.

Therefore, he and his colleagues used a systems biology approach to demonstrate the time-dependent bias in static proliferation assays and to develop the time-independent DIP rate metric.

The researchers evaluated the responses of 4 different melanoma cell lines to the drug vemurafenib, currently used to treat melanoma, with the standard metric and with the DIP rate.

In one cell line, the team found a stark disagreement between the two metrics.

“The static metric says that the cell line is very sensitive to vemurafenib,” said Leonard Harris, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“However, our analysis shows this is not the case. A brief period of drug sensitivity, quickly followed by rebound, fools the static metric but not the DIP rate.”

The findings “suggest we should expect melanoma tumors treated with this drug to come back, and that’s what has happened, puzzling investigators,” Dr Quaranta said. “DIP rate analyses may help solve this conundrum, leading to better treatment strategies.”

These findings have particular importance in light of recent international efforts to generate data sets that include the responses of “thousands of cell lines to hundreds of compounds,” Dr Quaranta said.

The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) databases include drug response data along with genomic and proteomic data that detail each cell line’s molecular makeup.

“The idea is to look for statistical correlations—these particular cell lines with this particular makeup are sensitive to these types of compounds—to use these large databases as discovery tools for new therapeutic targets in cancer,” Dr Quaranta said. “If the metric by which you’ve evaluated the drug sensitivity of the cells is wrong, your statistical correlations are basically no good.”

Therapy may reduce memory problems related to chemo

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A type of cognitive behavioral therapy may help prevent some of the long-term memory issues caused by chemotherapy, according to research published in Cancer.

The therapy is called “Memory and Attention Adaptation Training” (MAAT).

It’s designed to help cancer survivors increase awareness of situations where memory problems can arise and develop skills to either prevent memory failure or compensate for memory dysfunction.

MAAT was developed by Robert Ferguson, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues.

The researchers tested MAAT in a small, randomized study of 47 Caucasian breast cancer survivors who were an average of 4 years post-chemotherapy.

The patients were assigned to 8 visits of MAAT (30 to 45 minutes each visit) or supportive talk therapy for an identical time span. The intent of the supportive therapy was to control for the simple effects of interacting with a supportive clinician, or “behavioral placebo.”

Both treatments were delivered over a videoconference network between health centers to minimize patient travel.

All participants completed questionnaires assessing perceived memory difficulty and anxiety about memory problems. They were also tested over the phone with neuropsychological tests of verbal memory and processing speed, or the ability to automatically and fluently perform relatively easy cognitive tasks.

Participants were evaluated again after the 8 MAAT and supportive therapy videoconference visits, as well as 2 months after the conclusion of these therapies.

Compared with participants who received supportive therapy, MAAT participants reported significantly fewer memory problems (P=0.02) and improved processing speed post-treatment (P=0.03).

MAAT participants also reported less anxiety about cognitive problems compared with supportive therapy participants 2 months after MAAT concluded, but this was not a statistically significant finding.

“This is what we believe is the first randomized study with an active control condition that demonstrates improvement in cognitive symptoms in breast cancer survivors with long-term memory complaints,” Dr Ferguson said. “MAAT participants reported reduced anxiety and high satisfaction with this cognitive behavioral, non-drug approach.”

“Because treatment was delivered over videoconference device, this study demonstrates MAAT can be delivered electronically and survivors can reduce or eliminate travel to a cancer center. This can improve access to survivorship care.”

Dr Ferguson also noted that more research on MAAT is needed using a larger number of individuals with varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds and multiple clinicians delivering treatment.

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A type of cognitive behavioral therapy may help prevent some of the long-term memory issues caused by chemotherapy, according to research published in Cancer.

The therapy is called “Memory and Attention Adaptation Training” (MAAT).

It’s designed to help cancer survivors increase awareness of situations where memory problems can arise and develop skills to either prevent memory failure or compensate for memory dysfunction.

MAAT was developed by Robert Ferguson, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues.

The researchers tested MAAT in a small, randomized study of 47 Caucasian breast cancer survivors who were an average of 4 years post-chemotherapy.

The patients were assigned to 8 visits of MAAT (30 to 45 minutes each visit) or supportive talk therapy for an identical time span. The intent of the supportive therapy was to control for the simple effects of interacting with a supportive clinician, or “behavioral placebo.”

Both treatments were delivered over a videoconference network between health centers to minimize patient travel.

All participants completed questionnaires assessing perceived memory difficulty and anxiety about memory problems. They were also tested over the phone with neuropsychological tests of verbal memory and processing speed, or the ability to automatically and fluently perform relatively easy cognitive tasks.

Participants were evaluated again after the 8 MAAT and supportive therapy videoconference visits, as well as 2 months after the conclusion of these therapies.

Compared with participants who received supportive therapy, MAAT participants reported significantly fewer memory problems (P=0.02) and improved processing speed post-treatment (P=0.03).

MAAT participants also reported less anxiety about cognitive problems compared with supportive therapy participants 2 months after MAAT concluded, but this was not a statistically significant finding.

“This is what we believe is the first randomized study with an active control condition that demonstrates improvement in cognitive symptoms in breast cancer survivors with long-term memory complaints,” Dr Ferguson said. “MAAT participants reported reduced anxiety and high satisfaction with this cognitive behavioral, non-drug approach.”

“Because treatment was delivered over videoconference device, this study demonstrates MAAT can be delivered electronically and survivors can reduce or eliminate travel to a cancer center. This can improve access to survivorship care.”

Dr Ferguson also noted that more research on MAAT is needed using a larger number of individuals with varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds and multiple clinicians delivering treatment.

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A type of cognitive behavioral therapy may help prevent some of the long-term memory issues caused by chemotherapy, according to research published in Cancer.

The therapy is called “Memory and Attention Adaptation Training” (MAAT).

It’s designed to help cancer survivors increase awareness of situations where memory problems can arise and develop skills to either prevent memory failure or compensate for memory dysfunction.

MAAT was developed by Robert Ferguson, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues.

The researchers tested MAAT in a small, randomized study of 47 Caucasian breast cancer survivors who were an average of 4 years post-chemotherapy.

The patients were assigned to 8 visits of MAAT (30 to 45 minutes each visit) or supportive talk therapy for an identical time span. The intent of the supportive therapy was to control for the simple effects of interacting with a supportive clinician, or “behavioral placebo.”

Both treatments were delivered over a videoconference network between health centers to minimize patient travel.

All participants completed questionnaires assessing perceived memory difficulty and anxiety about memory problems. They were also tested over the phone with neuropsychological tests of verbal memory and processing speed, or the ability to automatically and fluently perform relatively easy cognitive tasks.

Participants were evaluated again after the 8 MAAT and supportive therapy videoconference visits, as well as 2 months after the conclusion of these therapies.

Compared with participants who received supportive therapy, MAAT participants reported significantly fewer memory problems (P=0.02) and improved processing speed post-treatment (P=0.03).

MAAT participants also reported less anxiety about cognitive problems compared with supportive therapy participants 2 months after MAAT concluded, but this was not a statistically significant finding.

“This is what we believe is the first randomized study with an active control condition that demonstrates improvement in cognitive symptoms in breast cancer survivors with long-term memory complaints,” Dr Ferguson said. “MAAT participants reported reduced anxiety and high satisfaction with this cognitive behavioral, non-drug approach.”

“Because treatment was delivered over videoconference device, this study demonstrates MAAT can be delivered electronically and survivors can reduce or eliminate travel to a cancer center. This can improve access to survivorship care.”

Dr Ferguson also noted that more research on MAAT is needed using a larger number of individuals with varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds and multiple clinicians delivering treatment.

Current cancer drug discovery method flawed, team says

Image courtesy of PNAS

The primary method used to test compounds for anticancer activity in vitro may produce inaccurate results, according to researchers.

Therefore, they have developed a new metric to evaluate a compound’s effect on cell proliferation—the drug-induced proliferation (DIP) rate.

They believe this metric, described in Nature Methods, overcomes the time-dependent bias of traditional proliferation assays.

“More than 90% of candidate cancer drugs fail in late-stage clinical trials, costing hundreds of millions of dollars,” said study author Vito Quaranta, MD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

“The flawed in vitro drug discovery metric may not be the only responsible factor, but it may be worth pursuing an estimate of its impact.”

For more than 30 years, scientists have evaluated the ability of a compound to kill cells by adding the compound and counting how many cells are alive after 72 hours.

However, these proliferation assays, which measure cell number at a single time point, don’t take into account the bias introduced by exponential cell proliferation, even in the presence of the drug, said study author Darren Tyson, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“Cells are not uniform,” added Dr Quaranta. “They all proliferate exponentially but at different rates. At 72 hours, some cells will have doubled 3 times, and others will not have doubled at all.”

In addition, he noted, drugs don’t all behave the same way on every cell line. For example, a drug might have an immediate effect on one cell line and a delayed effect on another.

Therefore, he and his colleagues used a systems biology approach to demonstrate the time-dependent bias in static proliferation assays and to develop the time-independent DIP rate metric.

The researchers evaluated the responses of 4 different melanoma cell lines to the drug vemurafenib, currently used to treat melanoma, with the standard metric and with the DIP rate.

In one cell line, the team found a stark disagreement between the two metrics.

“The static metric says that the cell line is very sensitive to vemurafenib,” said Leonard Harris, PhD, of Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

“However, our analysis shows this is not the case. A brief period of drug sensitivity, quickly followed by rebound, fools the static metric but not the DIP rate.”

The findings “suggest we should expect melanoma tumors treated with this drug to come back, and that’s what has happened, puzzling investigators,” Dr Quaranta said. “DIP rate analyses may help solve this conundrum, leading to better treatment strategies.”

These findings have particular importance in light of recent international efforts to generate data sets that include the responses of “thousands of cell lines to hundreds of compounds,” Dr Quaranta said.

The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) databases include drug response data along with genomic and proteomic data that detail each cell line’s molecular makeup.

“The idea is to look for statistical correlations—these particular cell lines with this particular makeup are sensitive to these types of compounds—to use these large databases as discovery tools for new therapeutic targets in cancer,” Dr Quaranta said. “If the metric by which you’ve evaluated the drug sensitivity of the cells is wrong, your statistical correlations are basically no good.”

Image courtesy of PNAS

The primary method used to test compounds for anticancer activity in vitro may produce inaccurate results, according to researchers.

Therefore, they have developed a new metric to evaluate a compound’s effect on cell proliferation—the drug-induced proliferation (DIP) rate.