User login

Medicare requires new modifier for CRC follow-on colonoscopy claims

To unlock this free benefit, providers must properly apply modifier KX.

What codes does this apply to?

Providers must append modifier KX (“requirements specified in the medical policy have been met”) to HCPCS codes G0105 and G0121 when the screening colonoscopy follows a positive result from one of the following noninvasive stool-based CRC screening tests:

- Screening Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT) (CPT 82270).

- Screening Immunoassay-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (iFOBT) (HCPCS G0328).

- Cologuard™ – Multi-target Stool DNA (sDNA) Test (CPT 81528).

What happens if I don’t use the KX modifier?

Medicare will return the screening colonoscopy claim as “unprocessable” and you will receive one of following messages:

CARC 16: “Claim/service lacks information or has submission billing error(s)” and RARC N822: “Missing Procedure Modifier(s)”

or

RARC N823: “Incomplete/Invalid Procedure Modifier”

Attach modifier KX and resubmit the claim to Medicare.

Should I use modifier KX if I remove polyps?

No. If you remove polyps during a screening colonoscopy following a positive noninvasive stool-based test, report the appropriate CPT code (for example, 45380, 45384, 45385, or 45388) and add modifier PT (colorectal cancer screening test; converted to diagnostic test or other procedure) to each CPT code for Medicare.

Some Medicare beneficiaries are not aware that Medicare has not fully eliminated the coinsurance responsibility yet when polypectomy is needed during a screening colonoscopy. Medicare beneficiary coinsurance responsibility is 15% of the cost of the procedure from 2023 to 2026. The coinsurance responsibility falls to 10% from 2027 to 2029 and by 2030 it will be covered 100% by Medicare.

Where can I find more information?

See the MLN Matters notice and the CMS Manual System.

To unlock this free benefit, providers must properly apply modifier KX.

What codes does this apply to?

Providers must append modifier KX (“requirements specified in the medical policy have been met”) to HCPCS codes G0105 and G0121 when the screening colonoscopy follows a positive result from one of the following noninvasive stool-based CRC screening tests:

- Screening Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT) (CPT 82270).

- Screening Immunoassay-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (iFOBT) (HCPCS G0328).

- Cologuard™ – Multi-target Stool DNA (sDNA) Test (CPT 81528).

What happens if I don’t use the KX modifier?

Medicare will return the screening colonoscopy claim as “unprocessable” and you will receive one of following messages:

CARC 16: “Claim/service lacks information or has submission billing error(s)” and RARC N822: “Missing Procedure Modifier(s)”

or

RARC N823: “Incomplete/Invalid Procedure Modifier”

Attach modifier KX and resubmit the claim to Medicare.

Should I use modifier KX if I remove polyps?

No. If you remove polyps during a screening colonoscopy following a positive noninvasive stool-based test, report the appropriate CPT code (for example, 45380, 45384, 45385, or 45388) and add modifier PT (colorectal cancer screening test; converted to diagnostic test or other procedure) to each CPT code for Medicare.

Some Medicare beneficiaries are not aware that Medicare has not fully eliminated the coinsurance responsibility yet when polypectomy is needed during a screening colonoscopy. Medicare beneficiary coinsurance responsibility is 15% of the cost of the procedure from 2023 to 2026. The coinsurance responsibility falls to 10% from 2027 to 2029 and by 2030 it will be covered 100% by Medicare.

Where can I find more information?

See the MLN Matters notice and the CMS Manual System.

To unlock this free benefit, providers must properly apply modifier KX.

What codes does this apply to?

Providers must append modifier KX (“requirements specified in the medical policy have been met”) to HCPCS codes G0105 and G0121 when the screening colonoscopy follows a positive result from one of the following noninvasive stool-based CRC screening tests:

- Screening Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT) (CPT 82270).

- Screening Immunoassay-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (iFOBT) (HCPCS G0328).

- Cologuard™ – Multi-target Stool DNA (sDNA) Test (CPT 81528).

What happens if I don’t use the KX modifier?

Medicare will return the screening colonoscopy claim as “unprocessable” and you will receive one of following messages:

CARC 16: “Claim/service lacks information or has submission billing error(s)” and RARC N822: “Missing Procedure Modifier(s)”

or

RARC N823: “Incomplete/Invalid Procedure Modifier”

Attach modifier KX and resubmit the claim to Medicare.

Should I use modifier KX if I remove polyps?

No. If you remove polyps during a screening colonoscopy following a positive noninvasive stool-based test, report the appropriate CPT code (for example, 45380, 45384, 45385, or 45388) and add modifier PT (colorectal cancer screening test; converted to diagnostic test or other procedure) to each CPT code for Medicare.

Some Medicare beneficiaries are not aware that Medicare has not fully eliminated the coinsurance responsibility yet when polypectomy is needed during a screening colonoscopy. Medicare beneficiary coinsurance responsibility is 15% of the cost of the procedure from 2023 to 2026. The coinsurance responsibility falls to 10% from 2027 to 2029 and by 2030 it will be covered 100% by Medicare.

Where can I find more information?

See the MLN Matters notice and the CMS Manual System.

Novel therapies for neuromuscular disease: What are the respiratory and sleep implications?

Sleep Medicine Network

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation & Neuromuscular Disease Section

Novel therapies for neuromuscular disease: What are the respiratory and sleep implications?

The natural history of respiratory impairment in children and adults with progressive neuromuscular disease (NMD) often follows a predictable progression. Muscle weakness leads to sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-related hypoventilation, followed by diurnal hypoventilation, and, ultimately leads to respiratory failure. A number of disease-specific and society guidelines provide protocols for anticipatory respiratory monitoring, such as the role of polysomnography, pulmonary function testing, and respiratory muscle strength testing. They also guide the treatment of respiratory symptoms, such as when to initiate cough augmentation and assisted ventilation.

including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. There are now cases of children with SMA type 1, who subsequent to treatment, are walking independently. Studies examining the impact of these therapies on motor function use standardized assessments, but there are limited studies assessing pulmonary and sleep outcomes (Gurbani N, et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56[4]:700).

Researchers are also assessing the role of home testing to diagnose hypoventilation (Shi J, et al. Sleep Med. 2023;101:221-7) and using tools like positive airway pressure device data to guide treatment with noninvasive ventilation (Perrem L et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55[1]:58-67). While these advances in therapy are exciting, we still do not know what the long-term respiratory function, prognosis, or disease progression may be. Questions remain regarding how to best monitor, and at what frequency to assess, the respiratory status in these patients.

Moshe Y. Prero, MD

Section Member-at-Large

Sleep Medicine Network

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation & Neuromuscular Disease Section

Novel therapies for neuromuscular disease: What are the respiratory and sleep implications?

The natural history of respiratory impairment in children and adults with progressive neuromuscular disease (NMD) often follows a predictable progression. Muscle weakness leads to sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-related hypoventilation, followed by diurnal hypoventilation, and, ultimately leads to respiratory failure. A number of disease-specific and society guidelines provide protocols for anticipatory respiratory monitoring, such as the role of polysomnography, pulmonary function testing, and respiratory muscle strength testing. They also guide the treatment of respiratory symptoms, such as when to initiate cough augmentation and assisted ventilation.

including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. There are now cases of children with SMA type 1, who subsequent to treatment, are walking independently. Studies examining the impact of these therapies on motor function use standardized assessments, but there are limited studies assessing pulmonary and sleep outcomes (Gurbani N, et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56[4]:700).

Researchers are also assessing the role of home testing to diagnose hypoventilation (Shi J, et al. Sleep Med. 2023;101:221-7) and using tools like positive airway pressure device data to guide treatment with noninvasive ventilation (Perrem L et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55[1]:58-67). While these advances in therapy are exciting, we still do not know what the long-term respiratory function, prognosis, or disease progression may be. Questions remain regarding how to best monitor, and at what frequency to assess, the respiratory status in these patients.

Moshe Y. Prero, MD

Section Member-at-Large

Sleep Medicine Network

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation & Neuromuscular Disease Section

Novel therapies for neuromuscular disease: What are the respiratory and sleep implications?

The natural history of respiratory impairment in children and adults with progressive neuromuscular disease (NMD) often follows a predictable progression. Muscle weakness leads to sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-related hypoventilation, followed by diurnal hypoventilation, and, ultimately leads to respiratory failure. A number of disease-specific and society guidelines provide protocols for anticipatory respiratory monitoring, such as the role of polysomnography, pulmonary function testing, and respiratory muscle strength testing. They also guide the treatment of respiratory symptoms, such as when to initiate cough augmentation and assisted ventilation.

including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. There are now cases of children with SMA type 1, who subsequent to treatment, are walking independently. Studies examining the impact of these therapies on motor function use standardized assessments, but there are limited studies assessing pulmonary and sleep outcomes (Gurbani N, et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56[4]:700).

Researchers are also assessing the role of home testing to diagnose hypoventilation (Shi J, et al. Sleep Med. 2023;101:221-7) and using tools like positive airway pressure device data to guide treatment with noninvasive ventilation (Perrem L et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55[1]:58-67). While these advances in therapy are exciting, we still do not know what the long-term respiratory function, prognosis, or disease progression may be. Questions remain regarding how to best monitor, and at what frequency to assess, the respiratory status in these patients.

Moshe Y. Prero, MD

Section Member-at-Large

Tobramycin inhaled solution and quality of life in patients with bronchiectasis

Airway Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis is a condition of dilated, inflamed airways and mucous production caused by a myriad of diseases. Bronchiectasis entails chronic productive cough and an increased risk of infections leading to exacerbations. Chronic bacterial infections are often a hallmark of severe disease, especially with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (O’Donnell AE. N Engl J Med. 2022;387[6]:533). Prophylactic inhaled antibiotics have been used as off-label therapies with mixed evidence, particularly in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (Rubin BK, et al. Respiration. 2014;88[3]:177).

In a recent publication, Guan and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of tobramycin inhaled solution (TIS) for bronchiectasis with chronic P. aeruginosa in a phase 3, 16-week, multicenter, double-blind randomized, controlled trial (Guan W-J, et al. Chest. 2023;163[1]:64). A regimen of twice-daily TIS, compared with nebulized normal saline, demonstrated a more significant reduction in P. aeruginosa sputum density after two cycles of 28 days on-treatment and 28 days off-treatment (adjusted mean difference, 1.74 log10 colony-forming units/g; 95% CI, 1.12-2.35; (P < .001), and more patients became culture-negative for P. aeruginosa in the TIS group than in the placebo group on day 29 (29.3% vs 10.6%). Adverse events were similar in both groups. Importantly, there was an improvement in quality-of-life bronchiectasis respiratory symptom score by 7.91 points at day 29 and 6.72 points at day 85; all three were statistically significant but just below the minimal clinically important difference of 8 points.

Dr. Conroy Wong and Dr. Miguel Angel Martinez-Garcia (Chest. 2023 Jan;163[1]:3) highlighted in their accompanying editorial that use of health-related quality of life score was a “distinguishing feature” of the trial as “most studies have used the change in microbial density as the primary outcome measure alone.”

Future studies evaluating cyclical vs continuous antibiotic administration, treatment duration, and impact on exacerbations continue to be needed.

Alicia Mirza, MD

Section Member-at-Large

Airway Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis is a condition of dilated, inflamed airways and mucous production caused by a myriad of diseases. Bronchiectasis entails chronic productive cough and an increased risk of infections leading to exacerbations. Chronic bacterial infections are often a hallmark of severe disease, especially with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (O’Donnell AE. N Engl J Med. 2022;387[6]:533). Prophylactic inhaled antibiotics have been used as off-label therapies with mixed evidence, particularly in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (Rubin BK, et al. Respiration. 2014;88[3]:177).

In a recent publication, Guan and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of tobramycin inhaled solution (TIS) for bronchiectasis with chronic P. aeruginosa in a phase 3, 16-week, multicenter, double-blind randomized, controlled trial (Guan W-J, et al. Chest. 2023;163[1]:64). A regimen of twice-daily TIS, compared with nebulized normal saline, demonstrated a more significant reduction in P. aeruginosa sputum density after two cycles of 28 days on-treatment and 28 days off-treatment (adjusted mean difference, 1.74 log10 colony-forming units/g; 95% CI, 1.12-2.35; (P < .001), and more patients became culture-negative for P. aeruginosa in the TIS group than in the placebo group on day 29 (29.3% vs 10.6%). Adverse events were similar in both groups. Importantly, there was an improvement in quality-of-life bronchiectasis respiratory symptom score by 7.91 points at day 29 and 6.72 points at day 85; all three were statistically significant but just below the minimal clinically important difference of 8 points.

Dr. Conroy Wong and Dr. Miguel Angel Martinez-Garcia (Chest. 2023 Jan;163[1]:3) highlighted in their accompanying editorial that use of health-related quality of life score was a “distinguishing feature” of the trial as “most studies have used the change in microbial density as the primary outcome measure alone.”

Future studies evaluating cyclical vs continuous antibiotic administration, treatment duration, and impact on exacerbations continue to be needed.

Alicia Mirza, MD

Section Member-at-Large

Airway Disorders Network

Bronchiectasis Section

Bronchiectasis is a condition of dilated, inflamed airways and mucous production caused by a myriad of diseases. Bronchiectasis entails chronic productive cough and an increased risk of infections leading to exacerbations. Chronic bacterial infections are often a hallmark of severe disease, especially with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (O’Donnell AE. N Engl J Med. 2022;387[6]:533). Prophylactic inhaled antibiotics have been used as off-label therapies with mixed evidence, particularly in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (Rubin BK, et al. Respiration. 2014;88[3]:177).

In a recent publication, Guan and colleagues evaluated the efficacy and safety of tobramycin inhaled solution (TIS) for bronchiectasis with chronic P. aeruginosa in a phase 3, 16-week, multicenter, double-blind randomized, controlled trial (Guan W-J, et al. Chest. 2023;163[1]:64). A regimen of twice-daily TIS, compared with nebulized normal saline, demonstrated a more significant reduction in P. aeruginosa sputum density after two cycles of 28 days on-treatment and 28 days off-treatment (adjusted mean difference, 1.74 log10 colony-forming units/g; 95% CI, 1.12-2.35; (P < .001), and more patients became culture-negative for P. aeruginosa in the TIS group than in the placebo group on day 29 (29.3% vs 10.6%). Adverse events were similar in both groups. Importantly, there was an improvement in quality-of-life bronchiectasis respiratory symptom score by 7.91 points at day 29 and 6.72 points at day 85; all three were statistically significant but just below the minimal clinically important difference of 8 points.

Dr. Conroy Wong and Dr. Miguel Angel Martinez-Garcia (Chest. 2023 Jan;163[1]:3) highlighted in their accompanying editorial that use of health-related quality of life score was a “distinguishing feature” of the trial as “most studies have used the change in microbial density as the primary outcome measure alone.”

Future studies evaluating cyclical vs continuous antibiotic administration, treatment duration, and impact on exacerbations continue to be needed.

Alicia Mirza, MD

Section Member-at-Large

The triple overlap: COPD-OSA-OHS. Is it time for new definitions?

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

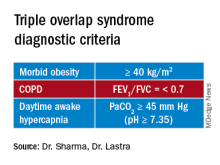

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

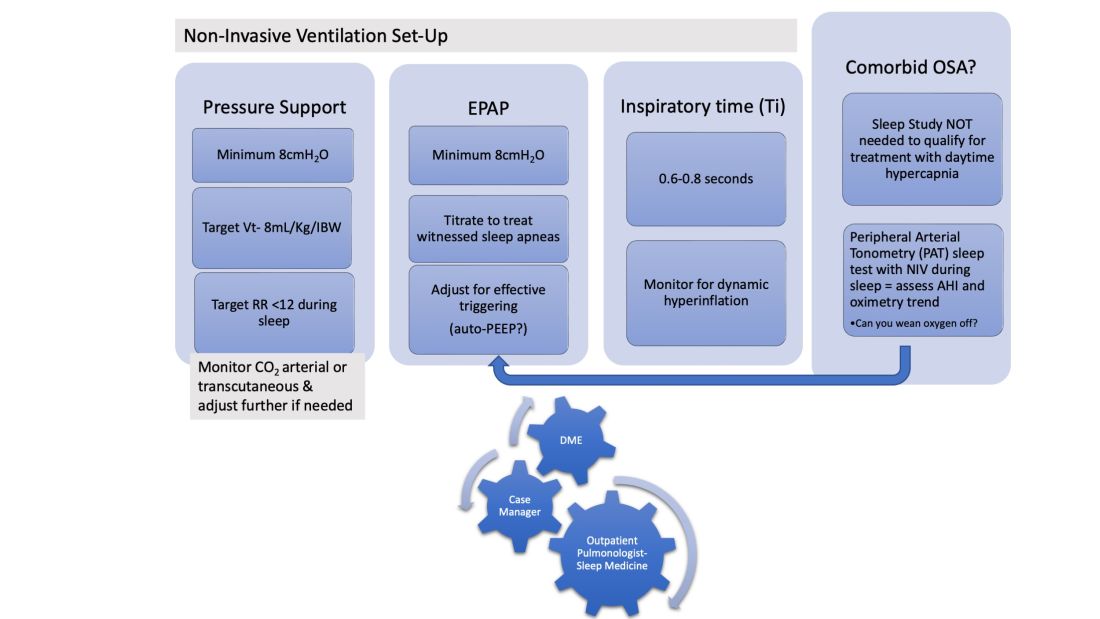

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

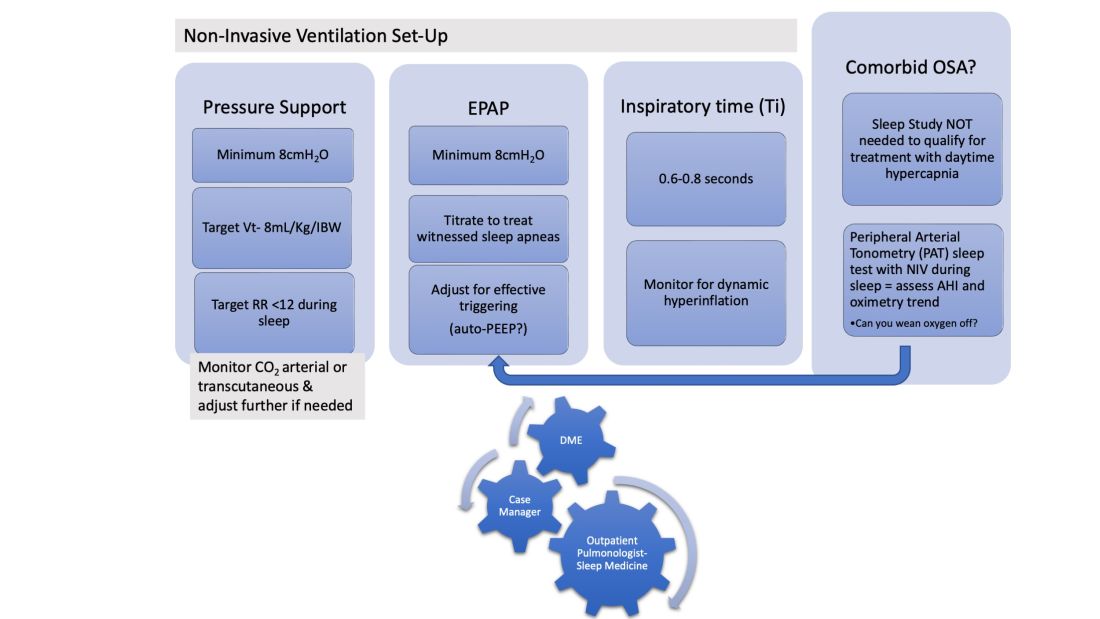

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

In our current society, it is likely that the “skinny patient with COPD” who walks into your clinic is less and less your “traditional” patient with COPD. We are seeing in our health care systems more of the “blue bloaters” – patients with COPD and significant obesity. This phenotype is representing what we are seeing worldwide as a consequence of the rising obesity prevalence. In the United States, the prepandemic (2017-2020) estimated percentage of adults over the age of 40 with obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2, was over 40%. Moreover, the estimated percentage of adults with morbid obesity (BMI at least 40 kg/m2) is close to 10% (Akinbami, LJ et al. Vital Health Stat. 2022:190:1-36) and trending up. These patients with the “triple overlap” of morbid obesity, COPD, and awake daytime hypercapnia are being seen in clinics and in-hospital settings with increasing frequency, often presenting with complicating comorbidities such as acute respiratory failure, acute heart failure, kidney disease, or pulmonary hypertension. We are now faced with managing these patients with complex disease.

The obesity paradox does not seem applicable in the triple overlap phenotype. Patients with COPD who are overweight, defined as “mild obesity,” have lower mortality when compared with normal weight and underweight patients with COPD; however, this effect diminishes when BMI increases beyond 32 kg/m2. With increasing obesity severity and aging, the risk of both obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and hypoventilation increases. It is well documented that COPD-OSA overlap is linked to worse outcomes and that continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) as first-line therapy decreases readmission rates and mortality. The pathophysiology of hypoventilation in obesity is complex and multifactorial, and, although significant overlaps likely exist with comorbid COPD, by current definitions, to establish a diagnosis of obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), one must have excluded other causes of hypoventilation, such as COPD.

These patients with the triple overlap of morbid obesity, awake daytime hypercapnia, and COPD are the subset of patients that providers struggle to fit in a diagnosis or in clinical research trials.

The triple overlap is a distinct syndrome

Different labels have been used in the medical literature: hypercapnic OSA-COPD overlap, morbid obesity and OSA-COPD overlap, hypercapnic morbidly obese COPD and OHS-COPD overlap. A better characterization of this distinctive phenotype is much needed. Patients with OSA-COPD overlap, for example, have an increased propensity to develop hypercapnia at higher FEV1 when compared with COPD without OSA – but this is thought to be a consequence of prolonged and frequent apneas and hypopneas compounded with obesity-related central hypoventilation. We found that morbidly obese patients with OSA-COPD overlap have a higher hypoxia burden, more severe OSA, and are frequently prescribed noninvasive ventilation after a failed titration polysomnogram (Htun ZM, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:A1382), perhaps signaling a distinctive phenotype with worse outcomes, but the study had the inherent limitations of a single-center, retrospective design lacking data on awake hypercapnia. On the other side, the term OHS-COPD is contradictory and confusing based on current OHS diagnostic criteria.

In standardizing diagnostic criteria for patients with this triple overlap syndrome, challenges remain: would the patient with a BMI of 70 kg/m2 and fixed chronic airflow obstruction with FEV1 72% fall under the category of hypercapnic COPD vs OHS? Do these patients have worse outcomes regardless of their predominant feature? Would outcomes change if the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) is 10/h vs 65/h? More importantly, do patients with the triple overlap of COPD, morbid obesity, and daytime hypercapnia have worse outcomes when compared with hypercapnic COPD, or OHS with/without OSA? These questions can be better addressed once we agree on a definition. The patients with triple overlap syndrome have been traditionally excluded from clinical trials: the patient with morbid obesity has been excluded from chronic hypercapnic COPD clinical trials, and the patient with COPD has been excluded from OHS trials.

There are no specific clinical guidelines for this triple overlap phenotype. Positive airway pressure is the mainstay of treatment. CPAP is recommended as first-line therapy for patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome, while noninvasive ventilation (NIV) with bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) is recommended as first-line for the stable ambulatory hypercapnic patient with COPD. It is unclear if NIV is superior to CPAP in patients with triple overlap syndrome, although recently published data showed greater efficacy in reducing carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and improving quality of life in a small group of subjects (Zheng et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18[1]:99-107). To take a step further, the subtleties of NIV set up, such as rise time and minimum inspiratory time, are contradictory: the goal in ventilating patients with COPD is to shorten inspiratory time, prolonging expiratory time, therefore allowing a shortened inspiratory cycle. In obesity, ventilation strategies aim to prolong and sustain inspiratory time to improve ventilation and dependent atelectasis. Another area of uncertainty is device selection. Should we aim to provide a respiratory assist device (RAD): the traditional, rent to own bilevel PAP without auto-expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) capabilities and lower maximum inspiratory pressure delivery capacity, vs a home mechanical ventilator at a higher expense, life-time rental, and one-way only data monitoring, which limits remote prescription adjustments, but allow auto-EPAP settings for patients with comorbid OSA? More importantly, how do we get these patients, who do not fit in any of the specified insurance criteria for PAP therapy approved for treatment?

A uniform diagnostic definition and clear taxonomy allows for resource allocation, from government funded grants for clinical trials to a better-informed distribution of health care systems resources and support health care policy changes to improve patient-centric outcomes. Here, we propose that the morbidly obese patient (BMI >40 kg/m2) with chronic airflow obstruction and a forced expiratory ratio (FEV1/FVC) <0.7 with awake daytime hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 45 mm Hg) represents a different entity/phenotype and fits best under the triple overlap syndrome taxonomy.

We suspect that these patients have worse outcomes, including comorbidity burden, quality of life, exacerbation rates, longer hospital length-of-stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. Large, multicenter, controlled trials comparing the long-term effectiveness of NIV and CPAP: measurements of respiratory function, gas exchange, blood pressure, and health related quality of life are needed. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from volume-targeted pressure support mode ventilation with auto-EPAP capabilities upon discharge from the hospital after an acute exacerbation.

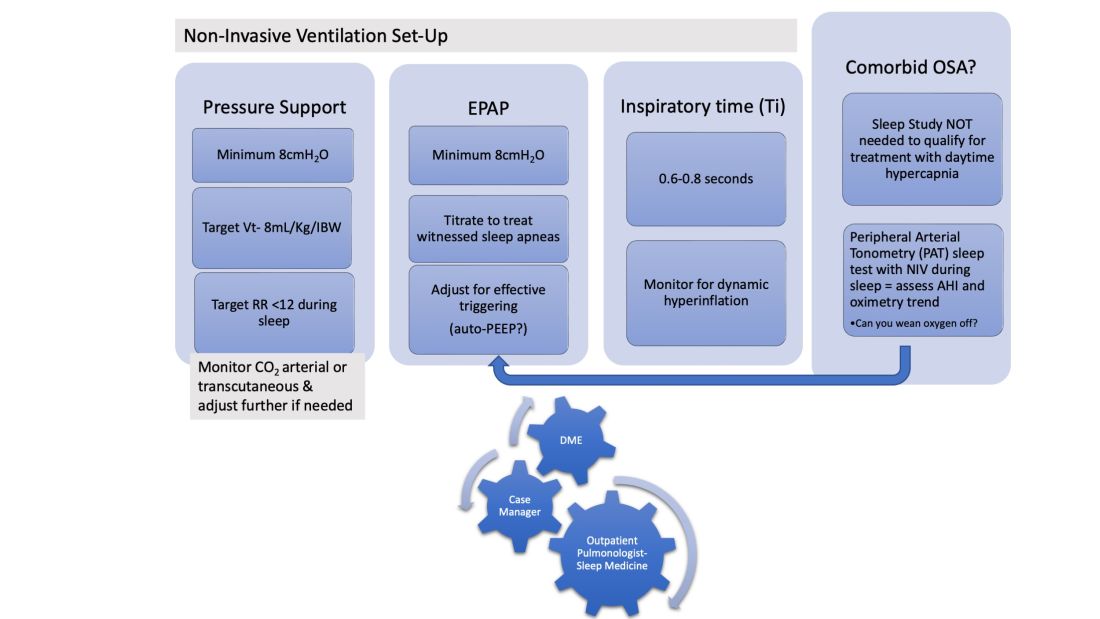

Inpatient (sleep medicine) and outpatient transitions

In patients hospitalized with the triple overlap syndrome, there are certain considerations that are of special interest. Given comorbid hypercapnia and limited data on NIV superiority over CPAP, a sleep study should not be needed for NIV qualification. In addition, the medical team may consider the following (Figure 1):

1. Noninvasive Ventilation:

a. Maintaining a high-pressure support differential between inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and EPAP. This can usually be achieved at 8-10 cm H2O, further adjusting to target a tidal volume (Vt) of 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).

b. Higher EPAP: To overcome dependent atelectasis, improve ventilation-perfusion (VQ) matching, and better treat upper airway resistance both during wakefulness and sleep. Also, adjustments of EPAP at bedside should be considered to counteract auto-PEEP-related ineffective triggering if observed.

c. OSA screening and EPAP adjustment: for high residual obstructive apneas or hypopneas if data are available on the NIV device, or with the use of peripheral arterial tonometry sleep testing devices with NIV on overnight before discharge.

d. Does the patient meet criteria for oxygen supplementation at home? Wean oxygen off, if possible.

2. Case-managers can help establish services with a durable medical equipment provider with expertise in advanced PAP devices.3. Obesity management, Consider referral to an obesity management program for lifestyle/dietary modifications along with pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery interventions.

4. Close follow-up, track exacerbations. Device download data are crucial to monitor adherence/tolerance and treatment effectiveness with particular interest in AHI, oximetry, and CO2 trends monitoring. Some patients may need dedicated titration polysomnograms to adjust ventilation settings, for optimization of residual OSA or for oxygen addition or discontinuation.

Conclusion

Patients with the triple overlap phenotype have not been systematically defined, studied, or included in clinical trials. We anticipate that these patients have worse outcomes: quality of life, symptom and comorbidity burden, exacerbation rates, in-hospital mortality, longer hospital stay and ICU stay, and respiratory and all-cause mortality. This is a group of patients that may specifically benefit from domiciliary NIV set-up upon discharge from the hospital with close follow-up. Properly identifying these patients will help pulmonologists and health care systems direct resources to optimally manage this complex group of patients. Funding of research trials to support clinical guidelines development should be prioritized. Triple overlap syndrome is different from COPD-OSA overlap, OHS with moderate to severe OSA, or OHS without significant OSA.

Introducing CHEST President-Designate John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

John A. Howington, MD, MBA, FCCP, is a cardiothoracic surgeon currently serving as Chief of Oncology Services and Chair of Thoracic Surgery at Ascension Saint Thomas Health and a professor at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Dr. Howington received his undergraduate degree from Tennessee Technological University and medical degree from the University of Tennessee. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Missouri, Kansas City and thoracic surgery residency at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Most recently, he received his Physician Executive MBA from the University of Tennessee.

As a passionate thoracic surgeon, he has lent his knowledge to the extensive CHEST lung cancer guideline portfolio for more than a decade. He offers regular leadership in multidisciplinary and executive forums and has spearheaded a series of quality improvement initiatives at Ascension. He has served in a variety of leadership roles with CHEST and with other national thoracic surgery societies.

Dr. Howington began his CHEST leadership journey with the Networks, as a member of the Interventional Chest Medicine Steering Committee and then as the Thoracic Oncology Network Chair (2008-2010).

Other leadership positions include serving as the President of the CHEST Foundation (2014-2016), member of the Scientific Program Committee and Membership Committee, and, recently, as the Chair of the Finance Committee from 2018-2021.

Since 2017, he has served on the Board of Regents as a Member at Large. Dr. Howington will serve as the 87th CHEST President in 2025.

A gift in your will: Getting started

A simple, flexible, and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue our work for years to come is a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest. To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust.

After your lifetime, the AGA Research Foundation receives your gift.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise, and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or percentage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

When planning a future gift, it’s sometimes difficult to determine what size donation will make sense. Emergencies happen, and you need to make sure your family is financially taken care of first. Including a bequest of a percentage of your estate ensures that your gift will remain proportionate no matter how your estate’s value fluctuates over the years.

Whether you would like to put your donation to work today or benefit us after your lifetime, you can find a charitable plan that lets you provide for your family and support the AGA Research Foundation.

Please contact us for more information at [email protected] or visit gastro.planmylegacy.org.

A simple, flexible, and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue our work for years to come is a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest. To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust.

After your lifetime, the AGA Research Foundation receives your gift.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise, and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or percentage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

When planning a future gift, it’s sometimes difficult to determine what size donation will make sense. Emergencies happen, and you need to make sure your family is financially taken care of first. Including a bequest of a percentage of your estate ensures that your gift will remain proportionate no matter how your estate’s value fluctuates over the years.

Whether you would like to put your donation to work today or benefit us after your lifetime, you can find a charitable plan that lets you provide for your family and support the AGA Research Foundation.

Please contact us for more information at [email protected] or visit gastro.planmylegacy.org.

A simple, flexible, and versatile way to ensure the AGA Research Foundation can continue our work for years to come is a gift in your will or living trust, known as a charitable bequest. To make a charitable bequest, you need a current will or living trust.

After your lifetime, the AGA Research Foundation receives your gift.

We hope you’ll consider including a gift to the AGA Research Foundation in your will or living trust. It’s simple – just a few sentences in your will or trust are all that is needed. The official bequest language for the AGA Research Foundation is: “I, [name], of [city, state, ZIP], give, devise, and bequeath to the AGA Research Foundation [written amount or percentage of the estate or description of property] for its unrestricted use and purpose.”

When planning a future gift, it’s sometimes difficult to determine what size donation will make sense. Emergencies happen, and you need to make sure your family is financially taken care of first. Including a bequest of a percentage of your estate ensures that your gift will remain proportionate no matter how your estate’s value fluctuates over the years.

Whether you would like to put your donation to work today or benefit us after your lifetime, you can find a charitable plan that lets you provide for your family and support the AGA Research Foundation.

Please contact us for more information at [email protected] or visit gastro.planmylegacy.org.

Critical Care Network

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

Mechanical Ventilation and Airways Section

Noninvasive ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) is a ventilation modality that supports breathing by using mechanically assisted breaths without the need for intubation or a surgical airway. NIV is divided into two main types, negative-pressure ventilation (NPV) and noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV).

NPV

NPV periodically generates a negative (subatmospheric) pressure on the thorax wall, reflecting the natural breathing mechanism. As this negative pressure is transmitted into the thorax, normal atmospheric pressure air outside the thorax is pulled in for inhalation. Initiated by the negative pressure generator switching off, exhalation is passive due to elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The iron lung was a neck-to-toe horizontal cylinder used for NPV during the polio epidemic. New NPV devices are designed to fit the thorax only, using a cuirass (a torso-covering body armor molded shell).

For years, NPV use declined as NIPPV use increased. However, during the shortage of NIPPV devices during COVID and a recent recall of certain CPAP devices, NPV use has increased. NPV is an excellent alternative for those who cannot tolerate a facial mask due to facial deformity, claustrophobia, or excessive airway secretion (Corrado A et al. European Resp J. 2002;20[1]:187).

NIPPV

NIPPV is divided into several subtypes, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP or BiPAP), and average volume-assured pressure support (AVAPS or VAPS). CPAP is defined as a single pressure delivered in inhalation (Pi) and exhalation (Pe). The increased mean airway pressure provides improved oxygenation (O2) but not ventilation (CO2). BPAP uses dual pressures with Pi higher than Pe. The increased mean airway pressure provides improved O2 while the difference between Pi minus Pe increases ventilation and decreases CO2.

AVAPS is a form of BPAP where Pi varies in an automated range to achieve the ordered tidal volume. In AVAPS, the generator adjusts Pi based on the average delivered tidal volume. If the average delivered tidal volume is less than the set tidal volume, Pi gradually increases while not exceeding Pi Max. Patients notice improved comfort of AVAPS with a variable Pi vs. BPAP with a fixed Pi (Frank A et al. Chest. 2018;154[4]:1060A).

Samantha Tauscher, DO, Resident-in-Training

Herbert Patrick, MD, MSEE, FCCP , Member-at-Large

COVID-19 ECMO and right ventricular failure: Lessons learned and standardization of management

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic changed the way intensivists approach extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) placed on ECMO have a high prevalence of right ventricular (RV) failure, which is associated with reduced survival (Maharaj V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68[6]:772). In 2021, our institution supported 51 patients with COVID-19 ARDS with ECMO: 51% developed RV failure, defined as a clinical syndrome (reduced cardiac output) in the presence of RV dysfunction on transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) (Marra A et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:535). Total numbers for RV dysfunction and RV dilation on TTE were 78% and 91% respectively, In essence then, TTE signs of RV dysfunction are sensitive but not specific for clinical RV failure.

Rates for survival to decannulation were far lower when RV failure was present (27%) vs. absent (84%). Given these numbers, we felt a reduction in RV failure would be an important target for improving outcomes for patients with COVID-19 ARDS receiving ECMO. Existing studies on RV failure in patients with ARDS receiving ECMO are plagued by scant data, small sample sizes, differences in diagnostic criteria, and heterogenous treatment approaches. Despite these limitations, we felt the need to make changes in our approach to RV management.

Because outcomes once clinical RV-failure occurs are so poor, we focused on prevention. While we’re short on data and evidence-based medicine (EBM) here, we know a lot about the physiology of COVID19, the pulmonary vasculature, and the right side of the heart. There are multiple physiologic and disease-related pathways that converge to produce RV-failure in patients with COVID-19 ARDS on ECMO (Sato R et al. Crit Care. 2021;25:172). Ongoing relative hypoxemia, hypercapnia, acidemia, and microvascular thromboses/immunothromboses can all lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and an increased workload for the RV (Zochios V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022; 68[4]:456). ARDS management typically involves high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), which can produce RV-PA uncoupling (Wanner P et al. J Clin Med. 2020;9:432).

We do know that ECMO relieves the stress on the right side of the heart by improving hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidemia while allowing for reduction in PEEP (Zochios V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022; 68[4]:456). In addition to ECMO, proning and pulmonary vasodilators offload RV by further reducing pulmonary pressures (Sato R et al. Crit Care. 2021;25:172). Lastly, a right ventricular assist device (RVAD) can dissipate the work required by the RV and prevent decompensation. Collectively, these therapies can be considered preventive.

Knowing the RV parameters on RV are sensitive but not specific for outcomes though, when should some of these treatments be instituted? It’s clear that once RV failure has developed it’s probably too late, but it’s hard to find data to guide us on when to act. One institution used right ventricular assist devices (RVADs) at the time of ECMO initiation with protocolized care and achieved a survival to discharge rate of 73% (Mustafa AK et al. JAMA Surgery. 2020;155[10]:990). The publication generated enthusiasm for RVAD support with ECMO, but it’s possible the protocolized care drove the high survival rate, at least in part.

At our institution, we developed our own protocol for evaluation of the RV with proactive treatment based on specific targets. We performed daily, bedside TTE and assessed the RV fractional area of change (FAC) and outflow tract velocity time integral (VTI). These parameters provide a quantitative assessment of global RV function, and FAC is directly related to ability to wean from ECMO support (Maharaj V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68[6]:772). We avoided using the tricuspid annular plain systolic excursion (TAPSE) due to its poor sensitivity (Marra AM et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:535). Patients receiving ECMO with subjective, global mild to moderate RV dysfunction on TTE with worsening clinical data, an FAC of 20%-35%, and a VTI of 10-14 cm were treated with aggressive diuresis, pulmonary vasodilators, and inotropy for 48 hours. If there was no improvement or deterioration, an RVAD was placed. For patients with signs of severe RV dysfunction (FAC < 20% or VTI < 10 cm), we proceeded directly to RVAD. We’re currently collecting data and tracking outcomes.

While data exist on various interventions in RV failure due to COVID-19 ARDS with ECMO, our understanding of this disease is still in its infancy. The optimal timing of interventions to manage and prevent RV failure is not known. We would argue that those who wait for RV failure to occur before instituting protective or supportive therapies are missing the opportunity to impact outcomes. We currently do not have the evidence to support the specific protocol we’ve outlined here and instituted at our hospital. However, we do believe there’s enough literature and experience to support the concept that close monitoring of RV function is critical for patients with COVID19 ARDS receiving ECMO. Failure to anticipate worsening function on the way to failure means reacting to it rather than staving it off. By then, it’s too late.

Dr. Thomas is Maj, USAF, assistant professor, pulmonary/critical care; Dr. O’Neil is Maj, USAF, pediatric and ECMO intensivist, PICU medical director; and Dr. Villalobos is Capt, USAF, assistant professor, pulmonary/critical care, medical ICU director, Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, Tex. The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, or the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic changed the way intensivists approach extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) placed on ECMO have a high prevalence of right ventricular (RV) failure, which is associated with reduced survival (Maharaj V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68[6]:772). In 2021, our institution supported 51 patients with COVID-19 ARDS with ECMO: 51% developed RV failure, defined as a clinical syndrome (reduced cardiac output) in the presence of RV dysfunction on transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) (Marra A et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:535). Total numbers for RV dysfunction and RV dilation on TTE were 78% and 91% respectively, In essence then, TTE signs of RV dysfunction are sensitive but not specific for clinical RV failure.

Rates for survival to decannulation were far lower when RV failure was present (27%) vs. absent (84%). Given these numbers, we felt a reduction in RV failure would be an important target for improving outcomes for patients with COVID-19 ARDS receiving ECMO. Existing studies on RV failure in patients with ARDS receiving ECMO are plagued by scant data, small sample sizes, differences in diagnostic criteria, and heterogenous treatment approaches. Despite these limitations, we felt the need to make changes in our approach to RV management.

Because outcomes once clinical RV-failure occurs are so poor, we focused on prevention. While we’re short on data and evidence-based medicine (EBM) here, we know a lot about the physiology of COVID19, the pulmonary vasculature, and the right side of the heart. There are multiple physiologic and disease-related pathways that converge to produce RV-failure in patients with COVID-19 ARDS on ECMO (Sato R et al. Crit Care. 2021;25:172). Ongoing relative hypoxemia, hypercapnia, acidemia, and microvascular thromboses/immunothromboses can all lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and an increased workload for the RV (Zochios V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022; 68[4]:456). ARDS management typically involves high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), which can produce RV-PA uncoupling (Wanner P et al. J Clin Med. 2020;9:432).

We do know that ECMO relieves the stress on the right side of the heart by improving hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and acidemia while allowing for reduction in PEEP (Zochios V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022; 68[4]:456). In addition to ECMO, proning and pulmonary vasodilators offload RV by further reducing pulmonary pressures (Sato R et al. Crit Care. 2021;25:172). Lastly, a right ventricular assist device (RVAD) can dissipate the work required by the RV and prevent decompensation. Collectively, these therapies can be considered preventive.

Knowing the RV parameters on RV are sensitive but not specific for outcomes though, when should some of these treatments be instituted? It’s clear that once RV failure has developed it’s probably too late, but it’s hard to find data to guide us on when to act. One institution used right ventricular assist devices (RVADs) at the time of ECMO initiation with protocolized care and achieved a survival to discharge rate of 73% (Mustafa AK et al. JAMA Surgery. 2020;155[10]:990). The publication generated enthusiasm for RVAD support with ECMO, but it’s possible the protocolized care drove the high survival rate, at least in part.

At our institution, we developed our own protocol for evaluation of the RV with proactive treatment based on specific targets. We performed daily, bedside TTE and assessed the RV fractional area of change (FAC) and outflow tract velocity time integral (VTI). These parameters provide a quantitative assessment of global RV function, and FAC is directly related to ability to wean from ECMO support (Maharaj V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68[6]:772). We avoided using the tricuspid annular plain systolic excursion (TAPSE) due to its poor sensitivity (Marra AM et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:535). Patients receiving ECMO with subjective, global mild to moderate RV dysfunction on TTE with worsening clinical data, an FAC of 20%-35%, and a VTI of 10-14 cm were treated with aggressive diuresis, pulmonary vasodilators, and inotropy for 48 hours. If there was no improvement or deterioration, an RVAD was placed. For patients with signs of severe RV dysfunction (FAC < 20% or VTI < 10 cm), we proceeded directly to RVAD. We’re currently collecting data and tracking outcomes.

While data exist on various interventions in RV failure due to COVID-19 ARDS with ECMO, our understanding of this disease is still in its infancy. The optimal timing of interventions to manage and prevent RV failure is not known. We would argue that those who wait for RV failure to occur before instituting protective or supportive therapies are missing the opportunity to impact outcomes. We currently do not have the evidence to support the specific protocol we’ve outlined here and instituted at our hospital. However, we do believe there’s enough literature and experience to support the concept that close monitoring of RV function is critical for patients with COVID19 ARDS receiving ECMO. Failure to anticipate worsening function on the way to failure means reacting to it rather than staving it off. By then, it’s too late.

Dr. Thomas is Maj, USAF, assistant professor, pulmonary/critical care; Dr. O’Neil is Maj, USAF, pediatric and ECMO intensivist, PICU medical director; and Dr. Villalobos is Capt, USAF, assistant professor, pulmonary/critical care, medical ICU director, Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, Tex. The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of Brooke Army Medical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, or the Department of Defense or the U.S. government.

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic changed the way intensivists approach extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) placed on ECMO have a high prevalence of right ventricular (RV) failure, which is associated with reduced survival (Maharaj V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68[6]:772). In 2021, our institution supported 51 patients with COVID-19 ARDS with ECMO: 51% developed RV failure, defined as a clinical syndrome (reduced cardiac output) in the presence of RV dysfunction on transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) (Marra A et al. Chest. 2022;161[2]:535). Total numbers for RV dysfunction and RV dilation on TTE were 78% and 91% respectively, In essence then, TTE signs of RV dysfunction are sensitive but not specific for clinical RV failure.

Rates for survival to decannulation were far lower when RV failure was present (27%) vs. absent (84%). Given these numbers, we felt a reduction in RV failure would be an important target for improving outcomes for patients with COVID-19 ARDS receiving ECMO. Existing studies on RV failure in patients with ARDS receiving ECMO are plagued by scant data, small sample sizes, differences in diagnostic criteria, and heterogenous treatment approaches. Despite these limitations, we felt the need to make changes in our approach to RV management.

Because outcomes once clinical RV-failure occurs are so poor, we focused on prevention. While we’re short on data and evidence-based medicine (EBM) here, we know a lot about the physiology of COVID19, the pulmonary vasculature, and the right side of the heart. There are multiple physiologic and disease-related pathways that converge to produce RV-failure in patients with COVID-19 ARDS on ECMO (Sato R et al. Crit Care. 2021;25:172). Ongoing relative hypoxemia, hypercapnia, acidemia, and microvascular thromboses/immunothromboses can all lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and an increased workload for the RV (Zochios V et al. ASAIO Journal. 2022; 68[4]:456). ARDS management typically involves high positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), which can produce RV-PA uncoupling (Wanner P et al. J Clin Med. 2020;9:432).