User login

Rivaroxaban doesn’t reduce risk of fatal VTE

MUNICH—Extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban does not significantly reduce the risk of fatal venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients hospitalized for medical illness, according to new research.

In the MARINER trial, the combined rate of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death was similar in patients who received placebo and those who received rivaroxaban for 45 days after hospital discharge.

Rates of VTE-related death were similar between the treatment groups, but the rate of nonfatal VTE was lower with rivaroxaban.

The researchers therefore concluded that some medically ill patients may benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban, although more research is needed.

Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, New York, presented these results at ESC Congress 2018.

The research was also published in NEJM. The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development.

The MARINER trial included 12,019 medically ill patients who had an increased risk of VTE and had been hospitalized for 3 to 10 days.

The patients were randomized to receive rivaroxaban (n=6007) at 10 mg daily (7.5 mg in patients with renal impairment) or daily placebo (n=6012) for 45 days after hospital discharge. In all, 11,962 patients (99.5%) received at least one dose of assigned treatment.

Results

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death. This endpoint was met in 0.83% (n=50) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 1.10% (n=66) of patients in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.76; P=0.136).

The incidence of VTE-related death was 0.72% (n=43) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.77% (n=46) in the placebo arm (HR=0.93, P=0.751).

The incidence of symptomatic VTE was 0.18% (n=11) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.42% (n=25) in the placebo arm (HR=0.44, P=0.023).

“We were able to reduce instances of non-fatal blood clots and pulmonary embolism by more than half, which shows that the use of direct oral anticoagulants . . . after the hospitalization of medically ill patients could help prevent clots from forming,” Dr. Spyropoulos said.

He and his colleagues also examined an exploratory secondary composite endpoint of symptomatic VTE and all-cause mortality and found that 1.30% (n=78) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm experienced an event, compared to 1.78% (n=107) of patients in the placebo arm (HR=0.73, P=0.033).

The study’s principal safety outcome was major bleeding. It occurred in 0.28% (n=17) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.15% (n=9) of those in the placebo arm (HR=1.88, P=0.124).

The difference in risk of major bleeding with rivaroxaban compared to placebo was 0.28 percentage points, and the difference in risk of symptomatic VTE with rivaroxaban vs placebo was -0.24 percentage points.

This suggests the number of patients needed to prevent one symptomatic VTE event is 430, and the number needed to cause one major bleed is 856.

Dr. Spyropoulos therefore concluded that thromboprophylaxis, when used in appropriate medically ill patients, might reduce the population health burden of symptomatic VTE with little serious bleeding.

“Our next course of research is to further identify and refine a post-discharge treatment program which would maximize the net clinical benefit across a defined spectrum of medically ill patients,” he said.

MUNICH—Extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban does not significantly reduce the risk of fatal venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients hospitalized for medical illness, according to new research.

In the MARINER trial, the combined rate of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death was similar in patients who received placebo and those who received rivaroxaban for 45 days after hospital discharge.

Rates of VTE-related death were similar between the treatment groups, but the rate of nonfatal VTE was lower with rivaroxaban.

The researchers therefore concluded that some medically ill patients may benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban, although more research is needed.

Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, New York, presented these results at ESC Congress 2018.

The research was also published in NEJM. The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development.

The MARINER trial included 12,019 medically ill patients who had an increased risk of VTE and had been hospitalized for 3 to 10 days.

The patients were randomized to receive rivaroxaban (n=6007) at 10 mg daily (7.5 mg in patients with renal impairment) or daily placebo (n=6012) for 45 days after hospital discharge. In all, 11,962 patients (99.5%) received at least one dose of assigned treatment.

Results

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death. This endpoint was met in 0.83% (n=50) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 1.10% (n=66) of patients in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.76; P=0.136).

The incidence of VTE-related death was 0.72% (n=43) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.77% (n=46) in the placebo arm (HR=0.93, P=0.751).

The incidence of symptomatic VTE was 0.18% (n=11) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.42% (n=25) in the placebo arm (HR=0.44, P=0.023).

“We were able to reduce instances of non-fatal blood clots and pulmonary embolism by more than half, which shows that the use of direct oral anticoagulants . . . after the hospitalization of medically ill patients could help prevent clots from forming,” Dr. Spyropoulos said.

He and his colleagues also examined an exploratory secondary composite endpoint of symptomatic VTE and all-cause mortality and found that 1.30% (n=78) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm experienced an event, compared to 1.78% (n=107) of patients in the placebo arm (HR=0.73, P=0.033).

The study’s principal safety outcome was major bleeding. It occurred in 0.28% (n=17) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.15% (n=9) of those in the placebo arm (HR=1.88, P=0.124).

The difference in risk of major bleeding with rivaroxaban compared to placebo was 0.28 percentage points, and the difference in risk of symptomatic VTE with rivaroxaban vs placebo was -0.24 percentage points.

This suggests the number of patients needed to prevent one symptomatic VTE event is 430, and the number needed to cause one major bleed is 856.

Dr. Spyropoulos therefore concluded that thromboprophylaxis, when used in appropriate medically ill patients, might reduce the population health burden of symptomatic VTE with little serious bleeding.

“Our next course of research is to further identify and refine a post-discharge treatment program which would maximize the net clinical benefit across a defined spectrum of medically ill patients,” he said.

MUNICH—Extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban does not significantly reduce the risk of fatal venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients hospitalized for medical illness, according to new research.

In the MARINER trial, the combined rate of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death was similar in patients who received placebo and those who received rivaroxaban for 45 days after hospital discharge.

Rates of VTE-related death were similar between the treatment groups, but the rate of nonfatal VTE was lower with rivaroxaban.

The researchers therefore concluded that some medically ill patients may benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban, although more research is needed.

Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Northwell Health at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York, New York, presented these results at ESC Congress 2018.

The research was also published in NEJM. The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development.

The MARINER trial included 12,019 medically ill patients who had an increased risk of VTE and had been hospitalized for 3 to 10 days.

The patients were randomized to receive rivaroxaban (n=6007) at 10 mg daily (7.5 mg in patients with renal impairment) or daily placebo (n=6012) for 45 days after hospital discharge. In all, 11,962 patients (99.5%) received at least one dose of assigned treatment.

Results

The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death. This endpoint was met in 0.83% (n=50) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 1.10% (n=66) of patients in the placebo arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.76; P=0.136).

The incidence of VTE-related death was 0.72% (n=43) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.77% (n=46) in the placebo arm (HR=0.93, P=0.751).

The incidence of symptomatic VTE was 0.18% (n=11) in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.42% (n=25) in the placebo arm (HR=0.44, P=0.023).

“We were able to reduce instances of non-fatal blood clots and pulmonary embolism by more than half, which shows that the use of direct oral anticoagulants . . . after the hospitalization of medically ill patients could help prevent clots from forming,” Dr. Spyropoulos said.

He and his colleagues also examined an exploratory secondary composite endpoint of symptomatic VTE and all-cause mortality and found that 1.30% (n=78) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm experienced an event, compared to 1.78% (n=107) of patients in the placebo arm (HR=0.73, P=0.033).

The study’s principal safety outcome was major bleeding. It occurred in 0.28% (n=17) of patients in the rivaroxaban arm and 0.15% (n=9) of those in the placebo arm (HR=1.88, P=0.124).

The difference in risk of major bleeding with rivaroxaban compared to placebo was 0.28 percentage points, and the difference in risk of symptomatic VTE with rivaroxaban vs placebo was -0.24 percentage points.

This suggests the number of patients needed to prevent one symptomatic VTE event is 430, and the number needed to cause one major bleed is 856.

Dr. Spyropoulos therefore concluded that thromboprophylaxis, when used in appropriate medically ill patients, might reduce the population health burden of symptomatic VTE with little serious bleeding.

“Our next course of research is to further identify and refine a post-discharge treatment program which would maximize the net clinical benefit across a defined spectrum of medically ill patients,” he said.

VTE risk unchanged by rivaroxaban after discharge

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

For patients hospitalized for medical illness, giving rivaroxaban after discharge does not significantly reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism, investigators reported.

Previous research suggested that the risk of major bleeding from rivaroxaban outweighed its benefits; however, major bleeding was uncommon in the MARINER trial, reported lead author Alex C. Spyropoulos, MD, of Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., and his colleagues.

“Patients who are hospitalized for acute medical illnesses, such as heart failure, respiratory insufficiency, stroke, and infectious or inflammatory diseases, are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. The results were also presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Although the increased risk of thromboembolism continues for at least 6 weeks after hospitalization, postdischarge anticoagulants, such as rivaroxaban, are controversial.

“Studies of extended thromboprophylaxis have shown either excess major bleeding or a benefit that is based mainly on reducing the risk of asymptomatic deep-vein thrombosis,” the investigators wrote.

The researchers aimed to clarify the benefits of rivaroxaban after hospitalization while modifying previous study regimens to limit major bleeding risk.

The double-blind MARINER study involved 12,019 patients who were hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. Hospitalization lasted 3-10 consecutive days. Sufficient risk of thromboembolism was defined by a modified International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism (IMPROVE) score of 4 or higher (range, 0-10), or an IMPROVE score of 2 or 3 with a plasma D-dimer measurement more than double the upper normal limit.

Patients were randomized to receive either 10 mg of rivaroxaban daily (n = 6,007) or placebo (n = 6,012) for 45 days after discharge. Patients with renal impairment had a reduced dose of 7.5 mg rivaroxaban.

A composite of symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism was the primary efficacy outcome. Major bleeding was the safety benchmark.

Efficacy was similar in both groups. Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 50 patients (0.83%) in the rivaroxaban group, compared with 66 patients (1.10%) in the placebo group (P = .14). These findings suggest that rivaroxaban provides a minor and insignificant benefit.

Although major bleeding was slightly more common in patients receiving rivaroxaban, compared with patients receiving placebo (0.28% vs. 0.15%), the researchers suggested that, in large populations, the marginal benefit of rivaroxaban might outweigh the increased bleeding risk. Still, the authors noted that “the usefulness of extended thromboprophylaxis remains uncertain.”

“Future studies should more accurately identify deaths caused by thrombotic mechanisms and focus on the patients who are at highest risk and who may benefit from anticoagulant prophylaxis,” the researchers wrote.

Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

SOURCE : Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Symptomatic or fatal venous thromboembolism occurred in 0.83% of patients given rivaroxaban, compared with 1.10% of patients given placebo (P = .14).

Study details: The MARINER study was a double-blind, randomized trial involving 12,019 patients. Patients were recently hospitalized for medical illness and had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by Janssen Research and Development. Most of the study authors reported fees or grants from Janssen during the study, and relationships with other companies outside of the submitted work.

Source: Spyropoulos AC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Aug 26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805090.

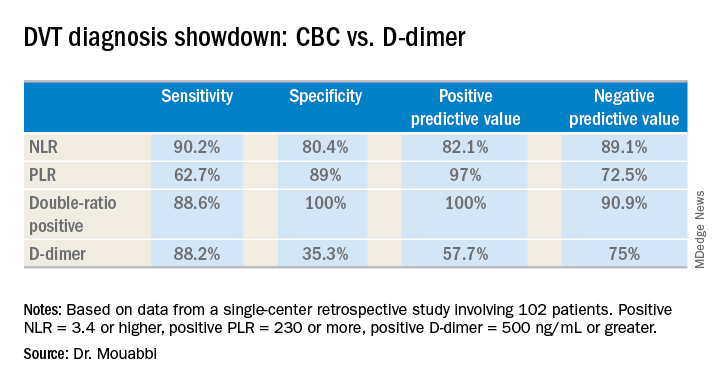

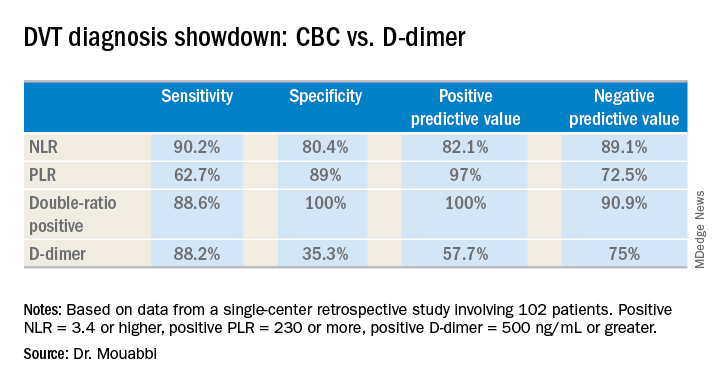

D-dimer and WCP can render VDUs unnecessary

Venous duplex ultrasounds (VDUs) may be over-utilized in patients suspected of having deep vein thrombosis (DVT), according to research published in Annals of Vascular Surgery.

The retrospective study indicated that D-dimer tests and the pretest Wells criteria probability (WCP) score could safely exclude DVT.

The researchers therefore believe that consistent use of D-dimer and WCP could reduce the number of unnecessary immediate VDUs, cut costs, and save time.

“Usually, waiting for a venous ultrasound would be a matter of three, four, five hours,” said study author Albeir Mousa, MD, of West Virginia University in Charleston, West Virginia.

“With the D-dimer test, it’s a few minutes, and you’re done.”

For this study, Dr. Mousa and his colleagues reviewed data on 1670 patients who presented to a high-volume tertiary care center with suspected DVT and were referred for VDU. Their average age was 62.1, and 55.7% were female.

The researchers calculated WCP scores for all 1670 patients and divided them into DVT risk groups accordingly—low- (<1), moderate- (1-2), and high-risk (≥3).

The team also divided patients according to D-dimer values—low (0.1-0.59), moderate (0.60-1.2), and high (≥1.3 mg/L FEU).

Results

The researchers found that D-dimer (with an abnormal threshold of ≥0.60 mg/L FEU) identified all patients with DVT (n=183, 11%).

The sensitivity and negative predictive values of D-dimer were both 100%, while specificity was 14.9% and the positive predictive value was 15.9%.

When the researchers used an age-adjusted D-dimer threshold (age x 0.01), the specificity increased from 14.9% to 21.3%, and the positive predictive value increased from 15.9% to 17%.

There were no DVTs among patients with low D-dimer values, but the rate of DVT significantly increased in the moderate (5.9%) and high groups (20.0%; P=0.007).

The rate of DVT increased with increasing WCP as well. The DVT rate was 6.6% in the low WCP group, 14% in the moderate group, and 29.1% in the high group (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted an increase in the rate of DVT across all levels of WCP as D-dimer levels increased.

Based on these findings, the researchers said there were 762 patients who were sent for unnecessary immediate VDUs. This included 685 patients in the low WCP group (<1) who did not undergo D-dimer testing, 51 patients who had moderate D-dimer values, and 26 who had low D-dimer values.

The researchers calculated the potential savings of using D-dimer instead of VDU in these patients, based on US 2016 dollar estimates.

A VDU cost of $1557 per person would mean a total cost of $1,186,434 for 762 patients. A D-dimer cost of $182 per person would mean a total cost of $138,684. So the total potential savings would be $1,047,750.

Dr. Mousa also noted that D-dimer testing is quicker than VDU and requires fewer resources.

“It’s a very simple sample of blood, which is sent to the lab,” he said. “And, usually in 15 or 20 minutes, you have significant information that can help you take good care of the patients. And you can send patients home quicker, with less demand on the hospital staff and the institution, yet increase patient satisfaction.”

Venous duplex ultrasounds (VDUs) may be over-utilized in patients suspected of having deep vein thrombosis (DVT), according to research published in Annals of Vascular Surgery.

The retrospective study indicated that D-dimer tests and the pretest Wells criteria probability (WCP) score could safely exclude DVT.

The researchers therefore believe that consistent use of D-dimer and WCP could reduce the number of unnecessary immediate VDUs, cut costs, and save time.

“Usually, waiting for a venous ultrasound would be a matter of three, four, five hours,” said study author Albeir Mousa, MD, of West Virginia University in Charleston, West Virginia.

“With the D-dimer test, it’s a few minutes, and you’re done.”

For this study, Dr. Mousa and his colleagues reviewed data on 1670 patients who presented to a high-volume tertiary care center with suspected DVT and were referred for VDU. Their average age was 62.1, and 55.7% were female.

The researchers calculated WCP scores for all 1670 patients and divided them into DVT risk groups accordingly—low- (<1), moderate- (1-2), and high-risk (≥3).

The team also divided patients according to D-dimer values—low (0.1-0.59), moderate (0.60-1.2), and high (≥1.3 mg/L FEU).

Results

The researchers found that D-dimer (with an abnormal threshold of ≥0.60 mg/L FEU) identified all patients with DVT (n=183, 11%).

The sensitivity and negative predictive values of D-dimer were both 100%, while specificity was 14.9% and the positive predictive value was 15.9%.

When the researchers used an age-adjusted D-dimer threshold (age x 0.01), the specificity increased from 14.9% to 21.3%, and the positive predictive value increased from 15.9% to 17%.

There were no DVTs among patients with low D-dimer values, but the rate of DVT significantly increased in the moderate (5.9%) and high groups (20.0%; P=0.007).

The rate of DVT increased with increasing WCP as well. The DVT rate was 6.6% in the low WCP group, 14% in the moderate group, and 29.1% in the high group (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted an increase in the rate of DVT across all levels of WCP as D-dimer levels increased.

Based on these findings, the researchers said there were 762 patients who were sent for unnecessary immediate VDUs. This included 685 patients in the low WCP group (<1) who did not undergo D-dimer testing, 51 patients who had moderate D-dimer values, and 26 who had low D-dimer values.

The researchers calculated the potential savings of using D-dimer instead of VDU in these patients, based on US 2016 dollar estimates.

A VDU cost of $1557 per person would mean a total cost of $1,186,434 for 762 patients. A D-dimer cost of $182 per person would mean a total cost of $138,684. So the total potential savings would be $1,047,750.

Dr. Mousa also noted that D-dimer testing is quicker than VDU and requires fewer resources.

“It’s a very simple sample of blood, which is sent to the lab,” he said. “And, usually in 15 or 20 minutes, you have significant information that can help you take good care of the patients. And you can send patients home quicker, with less demand on the hospital staff and the institution, yet increase patient satisfaction.”

Venous duplex ultrasounds (VDUs) may be over-utilized in patients suspected of having deep vein thrombosis (DVT), according to research published in Annals of Vascular Surgery.

The retrospective study indicated that D-dimer tests and the pretest Wells criteria probability (WCP) score could safely exclude DVT.

The researchers therefore believe that consistent use of D-dimer and WCP could reduce the number of unnecessary immediate VDUs, cut costs, and save time.

“Usually, waiting for a venous ultrasound would be a matter of three, four, five hours,” said study author Albeir Mousa, MD, of West Virginia University in Charleston, West Virginia.

“With the D-dimer test, it’s a few minutes, and you’re done.”

For this study, Dr. Mousa and his colleagues reviewed data on 1670 patients who presented to a high-volume tertiary care center with suspected DVT and were referred for VDU. Their average age was 62.1, and 55.7% were female.

The researchers calculated WCP scores for all 1670 patients and divided them into DVT risk groups accordingly—low- (<1), moderate- (1-2), and high-risk (≥3).

The team also divided patients according to D-dimer values—low (0.1-0.59), moderate (0.60-1.2), and high (≥1.3 mg/L FEU).

Results

The researchers found that D-dimer (with an abnormal threshold of ≥0.60 mg/L FEU) identified all patients with DVT (n=183, 11%).

The sensitivity and negative predictive values of D-dimer were both 100%, while specificity was 14.9% and the positive predictive value was 15.9%.

When the researchers used an age-adjusted D-dimer threshold (age x 0.01), the specificity increased from 14.9% to 21.3%, and the positive predictive value increased from 15.9% to 17%.

There were no DVTs among patients with low D-dimer values, but the rate of DVT significantly increased in the moderate (5.9%) and high groups (20.0%; P=0.007).

The rate of DVT increased with increasing WCP as well. The DVT rate was 6.6% in the low WCP group, 14% in the moderate group, and 29.1% in the high group (P<0.001).

The researchers also noted an increase in the rate of DVT across all levels of WCP as D-dimer levels increased.

Based on these findings, the researchers said there were 762 patients who were sent for unnecessary immediate VDUs. This included 685 patients in the low WCP group (<1) who did not undergo D-dimer testing, 51 patients who had moderate D-dimer values, and 26 who had low D-dimer values.

The researchers calculated the potential savings of using D-dimer instead of VDU in these patients, based on US 2016 dollar estimates.

A VDU cost of $1557 per person would mean a total cost of $1,186,434 for 762 patients. A D-dimer cost of $182 per person would mean a total cost of $138,684. So the total potential savings would be $1,047,750.

Dr. Mousa also noted that D-dimer testing is quicker than VDU and requires fewer resources.

“It’s a very simple sample of blood, which is sent to the lab,” he said. “And, usually in 15 or 20 minutes, you have significant information that can help you take good care of the patients. And you can send patients home quicker, with less demand on the hospital staff and the institution, yet increase patient satisfaction.”

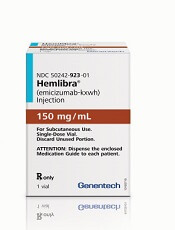

Replacing warfarin with a NOAC in patients on chronic anticoagulation therapy

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

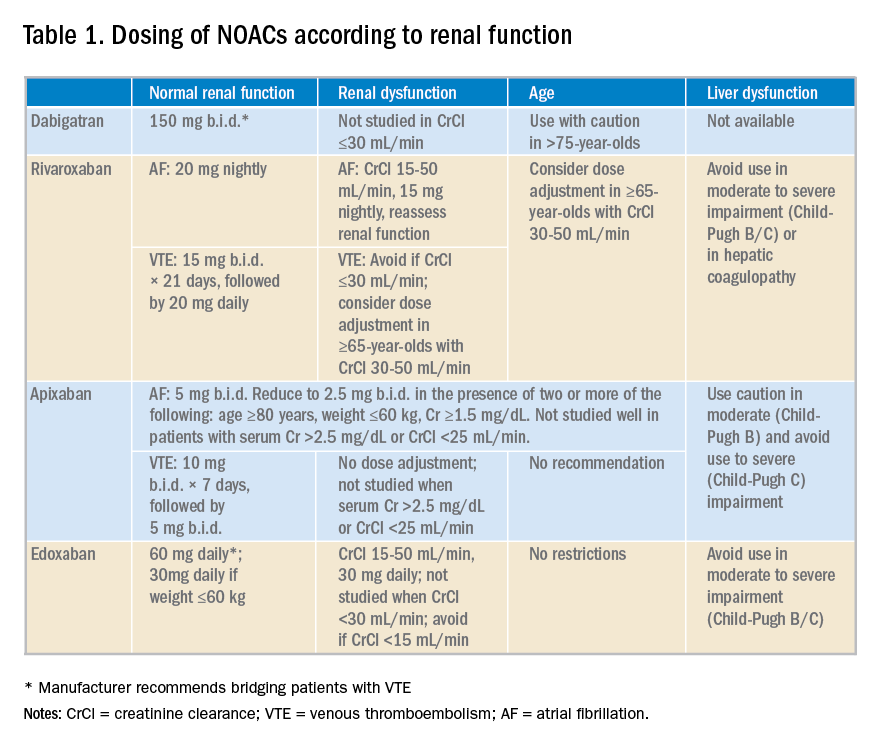

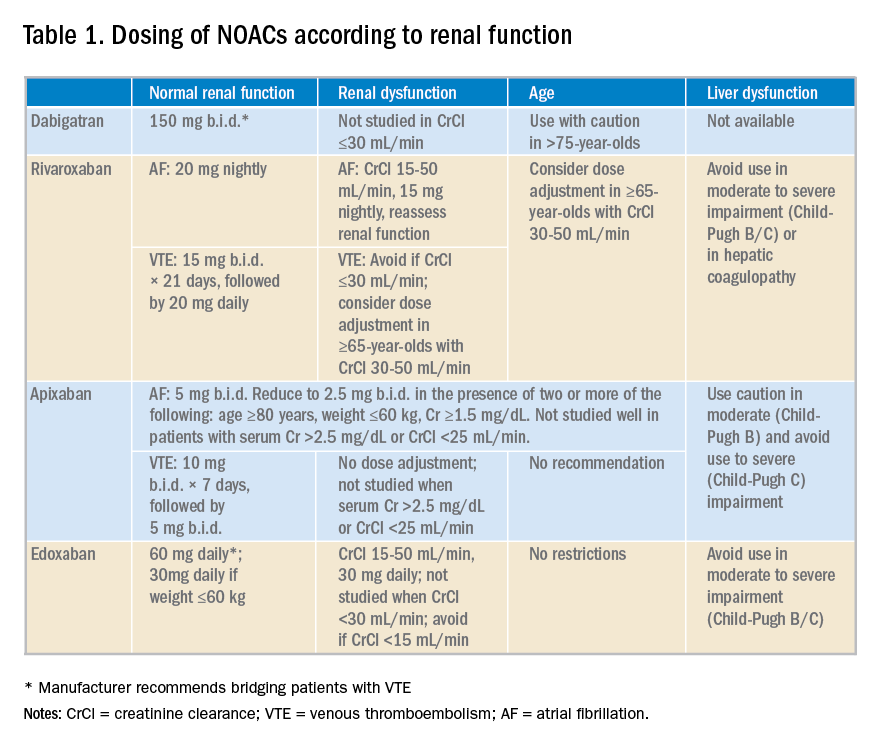

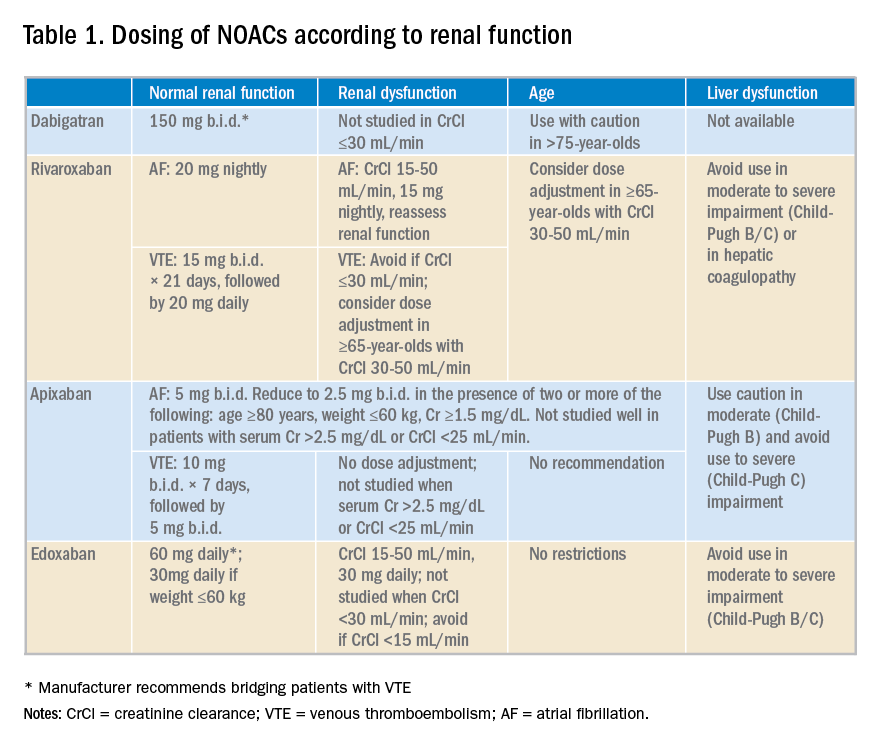

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

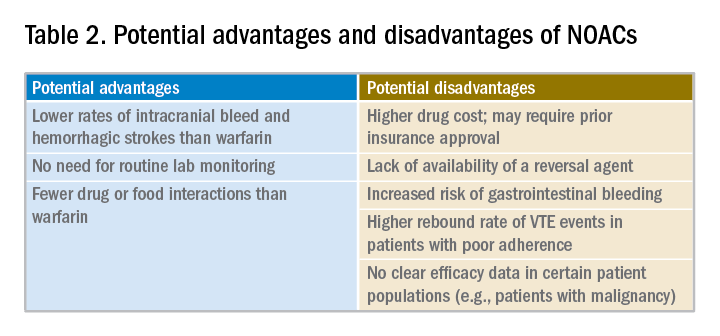

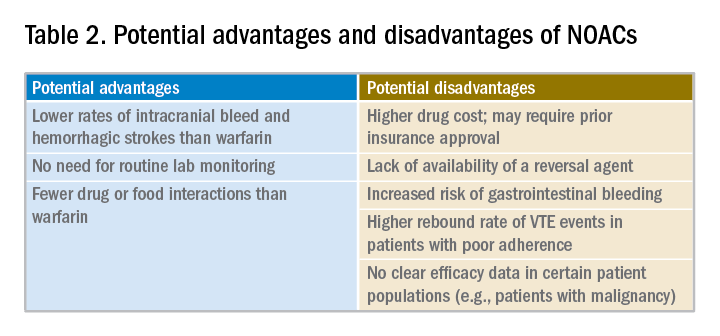

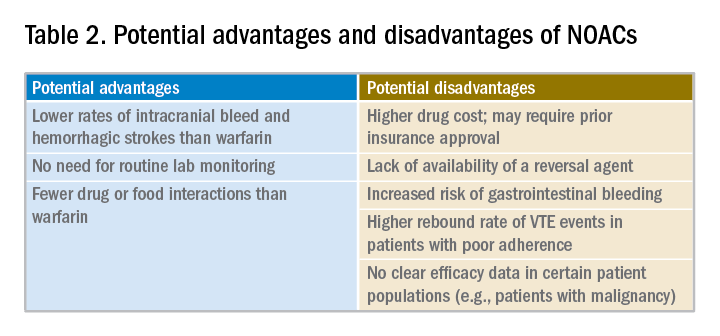

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Hospitalists must consider clinical factors and patient preferences

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

Case

A 70-year old woman with hypertension, diabetes, nonischemic stroke, moderate renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance [CrCl] 45 mL/min), heart failure, and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin is admitted because of a very supratherapeutic INR. She reports labile INR values despite strict adherence to her medication regimen. Her cancer screening tests had previously been unremarkable. She inquires about the risks and benefits of switching to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) as advertised on television. Should you consider it while she is still in the hospital?

Brief overview of the issue

Lifelong anticoagulation therapy is common among patients with AF or recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE). Until the advent of NOACs, a great majority of patients were prescribed warfarin, the oral vitamin K antagonist that requires regular blood tests for monitoring of the INR. In contrast to warfarin, NOACs are direct-acting agents (hence also known as “direct oral anticoagulants” or DOACs) that are selective for one specific coagulation factor, either thrombin (e.g., dabigatran) or factor Xa (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban, all with an “X” in their names).

NOACS have been studied and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for nonvalvular AF, i.e., patients without rheumatic mitral stenosis, mechanical or bioprosthetic heart valve, or prior mitral valve repair. Compared to warfarin, NOACS have fewer drug or food interactions, have more predictable pharmacokinetics, and may be associated with reduced risk of major bleeding depending on the agent. The latter is a particularly attractive feature of NOAC therapy, especially when its use is considered among older patients at risk of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), such as those with previous strokes, ICH, or reduced renal function. Unfortunately, data on the efficacy and safety of the use of NOACs in certain patient populations (e.g., those with severe renal insufficiency, active malignancy, the elderly, patients with suboptimal medication adherence) are generally lacking.

Overview of the data

There are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the clinical benefits of switching from warfarin to NOAC therapy. However, based on a number of RCTs comparing warfarin to individual NOACs and their related meta-analyses, the following conclusions may be made about their attributes:

1. Noninferiority to warfarin in reducing the risk of ischemic stroke in AF.

2. Association with a lower rate of major bleeds (statistically significant or trend) and a lower rate of ICH and hemorrhagic strokes compared to warfarin.

3. Association with a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding compared to warfarin (except for apixaban, low-dose dabigatran, and edoxaban1).

4. Association with a decreased rate of all stroke and thromboembolism events compared to warfarin.

5. Association with a slightly decreased all-cause mortality in AF compared to warfarin in many studies,2-8 but not all.1,9

6. Noninferiority to warfarin in all-cause mortality in patients with VTE and for its secondary prevention.1,4

NOACS should be used with caution or avoided altogether in patients with severe liver disease or renal insufficiency (see Table 1).

Potential advantages and disadvantages of NOAC therapy are listed in Table 2.

It should be emphasized that in patients with cancer or hypercoagulable state, no clear efficacy or safety data are currently available for the use of NOACs.

The 2016 CHEST guideline on antithrombotic therapy for VTE recommends NOACs over warfarin.10 The 2012 European Society of Cardiology AF guidelines also recommend NOACs over warfarin.11 However, the 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines on AF state that it is not necessary to change to a NOAC when patients are “stable, easily controlled, and satisfied with warfarin therapy.”12

Data from a relatively small, short-term study examining the safety of switching patients from warfarin to a NOAC suggest that although bleeding events are relatively common (12%) following such a switch, major bleeding and cardiac or cerebrovascular events are rare.10

Application of the data to our original case

Given a high calculated CHADS2VASC score of 8 in our patient, she has a clear indication for anticoagulation for AF. Her history of labile INRs, ischemic stroke, and moderate renal insufficiency place her at high risk for ICH.

A NOAC may reduce this risk but possibly at the expense of an increased risk for a gastrointestinal bleed. More importantly, however, she may be a good candidate for a switch to a NOAC because of her labile INRs despite good medication adherence. Her warfarin can be held while hospitalized and a NOAC may be initiated when the INR falls below 2.

Prior to discharge, potential cost of the drug to the patient should be explored and discussed. It is also important to involve the primary care physician in the decision-making process. Ultimately, selection of an appropriate NOAC should be based on a careful review of its risks and benefits, clinical factors, patient preference, and shared decision making.

Bottom line

Hospitalists are in a great position to discuss a switch to a NOAC in selected patients with history of good medication adherence and labile INRs or ICH risk factors.

Dr. Geisler, Dr. Liao, and Dr. Manian are hospitalists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

References

1. Sharma M et al. Efficacy and harms of direct oral anticoagulants in the elderly for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation and secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2015;132(3):194-204.

2. Ruff CT et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-62.

3. Dentali F et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Circulation. 2012;126(20):2381-91.

4. Adam SS et al. Comparative effectiveness of warfarin and new oral anticoagulants for the management of atrial fibrillation and venous thromboembolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):796-807.

5. Bruins Slot KM and Berge E. Factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(8):CD008980.

6. Gomez-Outes A et al. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of subgroups. Thrombosis. 2013;2013:640723.

7. Miller CS et al. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453-60.

8. Baker WL and Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):711-19.

9. Ntaios G et al. Nonvitamin-K-antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischemic attack: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3298-304.

10. Kearon C et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315-52.

11. Camm AJ et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation – developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14(10):1385-413.

12. January CT et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):e199-267.

Quiz

When considering a switch from warfarin to a NOAC, all the following factors should be considered a potential advantage, except:

A. No need for routing lab monitoring.

B. Lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

C. Fewer drug interactions.

D. Lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke.

The correct answer is B. NOACs have been associated with lower risk of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic stroke but not gastrointestinal bleed. Routine lab monitoring is not necessary during their use and they are associated with fewer drug interactions compared to warfarin.

Key Points

- NOACs represent a clear advancement in our anticoagulation armamentarium.

- Potential advantages of their use include lower rates of intracranial bleed and hemorrhagic strokes, fewer drug or food interactions, and lack of need for routing lab monitoring.

- Potential disadvantages of their use include increased rates of gastrointestinal bleed with some agents, general lack of availability of reversal agents, higher drug cost, unsuitability in patients with poor medication compliance, and lack of efficacy data in certain patient populations.

- Decision to switch from warfarin to a NOAC should thoroughly consider its pros and cons, clinical factors, and patient preferences.

FDA grants priority review to drug for PNH

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for ALXN1210, a long-acting C5 complement inhibitor.

With this BLA, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is seeking approval for ALXN1210 for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA for ALXN1210 by February 18, 2019.

The application is supported by data from a pair of phase 3 trials—PNH-301 and the Switch trial. Alexion released topline results from the PNH-301 trial in March and the Switch trial in April.

PNH-301 trial

This study enrolled 246 adults (age 18+) with PNH who were naïve to treatment with a complement inhibitor. Patients received ALXN1210 (n=125) or eculizumab (n=121).

Patients in the ALXN1210 arm received a single loading dose of ALXN1210, followed by regular maintenance weight-based dosing every 8 weeks. Patients in the eculizumab arm received 4 weekly induction doses, followed by regular maintenance dosing every 2 weeks.

Both arms were treated for 26 weeks. All patients enrolled in an extension study of up to 2 years, during which they will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks.

The study’s co-primary endpoints are:

- Transfusion avoidance, which was defined as the proportion of patients who remain transfusion-free and do not require a transfusion per protocol-specified guidelines through day 183

- Normalization of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels as directly measured every 2 weeks by LDH levels ≤ 1 times the upper limit of normal from day 29 through day 183.

ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab for both primary endpoints. Specifically, 73.6% of patients in the ALXN1210 arm and 66.1% in the eculizumab arm were able to avoid transfusion. LDH normalization occurred in 53.6% and 49.4%, respectively.

ALXN1210 also demonstrated non-inferiority to eculizumab on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- Percentage change from baseline in LDH levels (-76.8% and -76.0%, respectively)

- Change from baseline in quality of life as assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue scale (7.1 and 6.4, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis (4.0% and 10.7%, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels (68.0% and 64.5%, respectively).

Alexion said there were no notable differences in the safety profiles for ALXN1210 and eculizumab. The most frequently observed adverse event (AE) was headache, and the most frequently observed serious AE was pyrexia.

One anti-drug antibody (ADA) was observed in the ALXN1210 arm and 1 in the eculizumab arm. There were no neutralizing antibodies detected and no cases of meningococcal infection.

Switch study

This study is a comparison of ALXN1210 and eculizumab in 195 adults (18+). At baseline, patients had a confirmed diagnosis of PNH, had LDH levels ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and had been treated with eculizumab for at least the past 6 months.

ALXN1210 was administered every 8 weeks, and eculizumab was administered every 2 weeks. The 26-week treatment period is followed by an extension period, in which all patients will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks for up to 2 years.

Alexion did not provide any efficacy data in its announcement of results. However, the company said ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab based on the primary endpoint of change in LDH levels.

Alexion also said ALXN1210 demonstrated non-inferiority on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- The proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis

- The change from baseline in quality of life as assessed via the FACIT-Fatigue Scale

- The proportion of patients avoiding transfusion

- The proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels.

ALXN1210 had a safety profile that is consistent with that seen for eculizumab, according to Alexion. The most frequently observed AEs were headache and upper respiratory infection. The most frequently observed serious AEs were pyrexia and hemolysis.

There were no treatment-emergent ADAs in the ALXN1210 arm, but one patient in the eculizumab arm did have ADAs. There were no neutralizing antibodies and no cases of meningococcal infection in either arm.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for ALXN1210, a long-acting C5 complement inhibitor.

With this BLA, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is seeking approval for ALXN1210 for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA for ALXN1210 by February 18, 2019.

The application is supported by data from a pair of phase 3 trials—PNH-301 and the Switch trial. Alexion released topline results from the PNH-301 trial in March and the Switch trial in April.

PNH-301 trial

This study enrolled 246 adults (age 18+) with PNH who were naïve to treatment with a complement inhibitor. Patients received ALXN1210 (n=125) or eculizumab (n=121).

Patients in the ALXN1210 arm received a single loading dose of ALXN1210, followed by regular maintenance weight-based dosing every 8 weeks. Patients in the eculizumab arm received 4 weekly induction doses, followed by regular maintenance dosing every 2 weeks.

Both arms were treated for 26 weeks. All patients enrolled in an extension study of up to 2 years, during which they will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks.

The study’s co-primary endpoints are:

- Transfusion avoidance, which was defined as the proportion of patients who remain transfusion-free and do not require a transfusion per protocol-specified guidelines through day 183

- Normalization of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels as directly measured every 2 weeks by LDH levels ≤ 1 times the upper limit of normal from day 29 through day 183.

ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab for both primary endpoints. Specifically, 73.6% of patients in the ALXN1210 arm and 66.1% in the eculizumab arm were able to avoid transfusion. LDH normalization occurred in 53.6% and 49.4%, respectively.

ALXN1210 also demonstrated non-inferiority to eculizumab on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- Percentage change from baseline in LDH levels (-76.8% and -76.0%, respectively)

- Change from baseline in quality of life as assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue scale (7.1 and 6.4, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis (4.0% and 10.7%, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels (68.0% and 64.5%, respectively).

Alexion said there were no notable differences in the safety profiles for ALXN1210 and eculizumab. The most frequently observed adverse event (AE) was headache, and the most frequently observed serious AE was pyrexia.

One anti-drug antibody (ADA) was observed in the ALXN1210 arm and 1 in the eculizumab arm. There were no neutralizing antibodies detected and no cases of meningococcal infection.

Switch study

This study is a comparison of ALXN1210 and eculizumab in 195 adults (18+). At baseline, patients had a confirmed diagnosis of PNH, had LDH levels ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and had been treated with eculizumab for at least the past 6 months.

ALXN1210 was administered every 8 weeks, and eculizumab was administered every 2 weeks. The 26-week treatment period is followed by an extension period, in which all patients will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks for up to 2 years.

Alexion did not provide any efficacy data in its announcement of results. However, the company said ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab based on the primary endpoint of change in LDH levels.

Alexion also said ALXN1210 demonstrated non-inferiority on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- The proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis

- The change from baseline in quality of life as assessed via the FACIT-Fatigue Scale

- The proportion of patients avoiding transfusion

- The proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels.

ALXN1210 had a safety profile that is consistent with that seen for eculizumab, according to Alexion. The most frequently observed AEs were headache and upper respiratory infection. The most frequently observed serious AEs were pyrexia and hemolysis.

There were no treatment-emergent ADAs in the ALXN1210 arm, but one patient in the eculizumab arm did have ADAs. There were no neutralizing antibodies and no cases of meningococcal infection in either arm.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the biologics license application (BLA) for ALXN1210, a long-acting C5 complement inhibitor.

With this BLA, Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., is seeking approval for ALXN1210 for the treatment of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH).

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency intends to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it rather than the standard 10 months.

The FDA expects to make a decision on the BLA for ALXN1210 by February 18, 2019.

The application is supported by data from a pair of phase 3 trials—PNH-301 and the Switch trial. Alexion released topline results from the PNH-301 trial in March and the Switch trial in April.

PNH-301 trial

This study enrolled 246 adults (age 18+) with PNH who were naïve to treatment with a complement inhibitor. Patients received ALXN1210 (n=125) or eculizumab (n=121).

Patients in the ALXN1210 arm received a single loading dose of ALXN1210, followed by regular maintenance weight-based dosing every 8 weeks. Patients in the eculizumab arm received 4 weekly induction doses, followed by regular maintenance dosing every 2 weeks.

Both arms were treated for 26 weeks. All patients enrolled in an extension study of up to 2 years, during which they will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks.

The study’s co-primary endpoints are:

- Transfusion avoidance, which was defined as the proportion of patients who remain transfusion-free and do not require a transfusion per protocol-specified guidelines through day 183

- Normalization of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels as directly measured every 2 weeks by LDH levels ≤ 1 times the upper limit of normal from day 29 through day 183.

ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab for both primary endpoints. Specifically, 73.6% of patients in the ALXN1210 arm and 66.1% in the eculizumab arm were able to avoid transfusion. LDH normalization occurred in 53.6% and 49.4%, respectively.

ALXN1210 also demonstrated non-inferiority to eculizumab on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- Percentage change from baseline in LDH levels (-76.8% and -76.0%, respectively)

- Change from baseline in quality of life as assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue scale (7.1 and 6.4, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis (4.0% and 10.7%, respectively)

- Proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels (68.0% and 64.5%, respectively).

Alexion said there were no notable differences in the safety profiles for ALXN1210 and eculizumab. The most frequently observed adverse event (AE) was headache, and the most frequently observed serious AE was pyrexia.

One anti-drug antibody (ADA) was observed in the ALXN1210 arm and 1 in the eculizumab arm. There were no neutralizing antibodies detected and no cases of meningococcal infection.

Switch study

This study is a comparison of ALXN1210 and eculizumab in 195 adults (18+). At baseline, patients had a confirmed diagnosis of PNH, had LDH levels ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and had been treated with eculizumab for at least the past 6 months.

ALXN1210 was administered every 8 weeks, and eculizumab was administered every 2 weeks. The 26-week treatment period is followed by an extension period, in which all patients will receive ALXN1210 every 8 weeks for up to 2 years.

Alexion did not provide any efficacy data in its announcement of results. However, the company said ALXN1210 proved non-inferior to eculizumab based on the primary endpoint of change in LDH levels.

Alexion also said ALXN1210 demonstrated non-inferiority on all 4 key secondary endpoints:

- The proportion of patients with breakthrough hemolysis

- The change from baseline in quality of life as assessed via the FACIT-Fatigue Scale

- The proportion of patients avoiding transfusion

- The proportion of patients with stabilized hemoglobin levels.

ALXN1210 had a safety profile that is consistent with that seen for eculizumab, according to Alexion. The most frequently observed AEs were headache and upper respiratory infection. The most frequently observed serious AEs were pyrexia and hemolysis.

There were no treatment-emergent ADAs in the ALXN1210 arm, but one patient in the eculizumab arm did have ADAs. There were no neutralizing antibodies and no cases of meningococcal infection in either arm.

Marzeptacog alfa may prevent bleeds in hemophilia A/B with inhibitors

BOSTON—The activated factor VIIa variant marzeptacog alfa has demonstrated efficacy as prophylaxis for patients with hemophilia A or B who also have inhibitors, according to researchers.

Three patients have completed dosing with marzeptacog alfa in a phase 2/3 study.

None of these patients experienced bleeding during treatment, and none have developed antidrug antibodies or reported injection site reactions.

As for the other 2 patients enrolled in this study, 1 withdrew consent, and 1 died of an adverse event unrelated to marzeptacog alfa.

Howard Levy, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, Inc., presented these data at the 2018 Hemophilia Drug Development Summit.

The trial is sponsored by Catalyst Biosciences, the company developing marzeptacog alfa.

Results

The goal of this ongoing trial is to determine whether daily subcutaneous injections of marzeptacog alfa can eliminate or minimize spontaneous bleeding episodes. The primary endpoint is a reduction in annualized bleed rate (ABR) compared to each individual’s recorded historical ABR.

Thus far, the trial has enrolled 5 patients with hemophilia A or B and inhibitors. (Catalyst would not disclose how many patients have hemophilia A and how many have hemophilia B).

One patient with a historic ABR of 26.7 completed the trial with no bleeds after 50 days of treatment with marzeptacog alfa at 60 µg/kg.

This patient had previously experienced a bleed on day 46 when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg, and the patient experienced another bleed 16 days after the end of dosing at 60 µg/kg.

A second patient with a historic ABR of 16.6 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg for 50 days.

And a third patient with a historic ABR of 15.9 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg for 44 days.

“The data from these 3 individuals support the efficacy of [marzeptacog alfa] to reduce annualized bleed rates after daily subcutaneous injections,” said Nassim Usman, PhD, chief executive officer of Catalyst Biosciences.

“Importantly, to date, we have not observed any injection site reactions nor any anti-drug antibodies after more than 200 subcutaneous doses of [marzeptacog alfa].”

A fourth patient with a historic ABR of 18.3 had a fatal hemorrhagic stroke on day 11 that was considered unrelated to marzeptacog alfa. The patient had previously treated hypertension that was going untreated at the time of death.

A fifth patient with a historic ABR of 12.2 withdrew consent.

BOSTON—The activated factor VIIa variant marzeptacog alfa has demonstrated efficacy as prophylaxis for patients with hemophilia A or B who also have inhibitors, according to researchers.

Three patients have completed dosing with marzeptacog alfa in a phase 2/3 study.

None of these patients experienced bleeding during treatment, and none have developed antidrug antibodies or reported injection site reactions.

As for the other 2 patients enrolled in this study, 1 withdrew consent, and 1 died of an adverse event unrelated to marzeptacog alfa.

Howard Levy, chief medical officer of Catalyst Biosciences, Inc., presented these data at the 2018 Hemophilia Drug Development Summit.

The trial is sponsored by Catalyst Biosciences, the company developing marzeptacog alfa.

Results

The goal of this ongoing trial is to determine whether daily subcutaneous injections of marzeptacog alfa can eliminate or minimize spontaneous bleeding episodes. The primary endpoint is a reduction in annualized bleed rate (ABR) compared to each individual’s recorded historical ABR.

Thus far, the trial has enrolled 5 patients with hemophilia A or B and inhibitors. (Catalyst would not disclose how many patients have hemophilia A and how many have hemophilia B).

One patient with a historic ABR of 26.7 completed the trial with no bleeds after 50 days of treatment with marzeptacog alfa at 60 µg/kg.

This patient had previously experienced a bleed on day 46 when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg, and the patient experienced another bleed 16 days after the end of dosing at 60 µg/kg.

A second patient with a historic ABR of 16.6 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg for 50 days.

And a third patient with a historic ABR of 15.9 had no bleeds when receiving marzeptacog alfa at 30 µg/kg for 44 days.

“The data from these 3 individuals support the efficacy of [marzeptacog alfa] to reduce annualized bleed rates after daily subcutaneous injections,” said Nassim Usman, PhD, chief executive officer of Catalyst Biosciences.

“Importantly, to date, we have not observed any injection site reactions nor any anti-drug antibodies after more than 200 subcutaneous doses of [marzeptacog alfa].”

A fourth patient with a historic ABR of 18.3 had a fatal hemorrhagic stroke on day 11 that was considered unrelated to marzeptacog alfa. The patient had previously treated hypertension that was going untreated at the time of death.