User login

Crohn Disease Treatment

Abdominal cramping and diarrhea

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

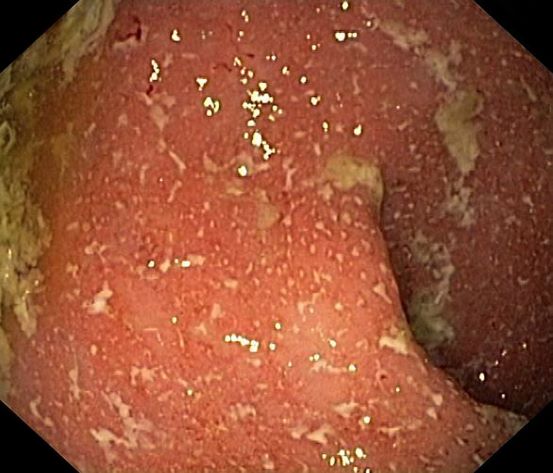

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

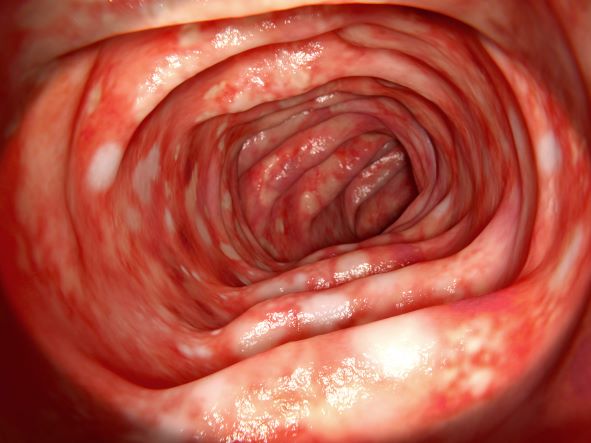

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, the likely diagnosis is extensive UC. Extensive colitis is defined by the presence of disease activity proximal to the splenic flexure. Because disease activity in UC is dynamic, up to half of patients who present with proctitis and 70% of those who present with left-sided colitis go on to develop extensive colitis on follow-up.

On the basis of the workup, it appears that this patient's UC has transitioned from left-sided to extensive disease, given the loss of treatment response. Endoscopic evaluation of patients with loss of treatment response may reveal patchiness of the histologic activity, as seen in this case.

Extensive colitis is a poor prognostic factor in UC, as is systemic steroid requirement, young age at diagnosis, and an elevated C-reactive protein level or erythrocyte sedimentation rate, all of which are associated with higher rates of colectomy. Over time, patients living with extensive ulcerative colitis develop an increased risk for colorectal cancer. Routine colonoscopic screening and surveillance are recommended for these high-risk patients.

UC most often presents as a continuously inflamed segment involving the distal rectum and extending proximally. Endoscopic features of inflammation include loss of vascular markings; granularity and friability of the mucosa; erosions; and, in the setting of severe inflammation, ulcerations and spontaneous bleeding. The diagnosis of UC involves both a lower gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and histologic confirmation. In general, a complete colonoscopy including examination of the terminal ileum should be performed, allowing clinicians to assess the full extent of the disease while ruling out distal ileal involvement, which is characteristic of Crohn's disease.

Evaluation of UC during relapses should include assessment of symptom severity and potential triggers, including enteric infections, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and recent smoking cessation. Nonadherence to therapy is common in patients with UC and may lead to relapse.

To treat a patient like the one represented here, the American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend oral 5-ASA at a dose of at least 2 g/d to induce remission. However, because this patient lost response to this treatment, the next step in the guidelines are appropriate oral systemic corticosteroids.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 46-year-old man presents with abdominal cramping and diarrhea and reports about five bowel movements per day for the past 2 weeks. Height is 5 ft 9 in and weight is 157 lb (BMI, 23.2). History is significant for ulcerative colitis (UC), diagnosed about 20 years ago with proctitis and having progressed about 8 years ago to left-sided disease. He smoked "lightly" through his 20s. Until about a month ago, the patient had been able to maintain remission with oral 5-aminosalicylic acid (ASA) therapy (2 g/d). Endoscopy shows granularity and friability of the mucosa with the inflamed segment extending proximal to the splenic flexure, though there is patchiness of the histologic activity. Colonoscopy rules out distal ileal involvement. Stool culture is negative.

Ulcerative Colitis Treatment

Symptoms of fatigue and abdominal pain

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of Crohn disease.

Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is becoming increasingly prevalent worldwide. It is estimated to affect three to 20 persons per 100,000. When not effectively managed, Crohn disease is associated with substantial morbidity and significant impairments in lifestyle and daily activities during flares and remissions. It is characterized by a transmural granulomatous inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract — usually, the ileum, colon, or both.

Abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue are often prominent symptoms in patients with Crohn disease. Crampy or steady right lower quadrant or periumbilical pain may develop; the pain both precedes and may be partially relieved by defecation. Diarrhea is frequently intermittent and is not usually grossly bloody. Diffuse abdominal pain accompanied by mucus, blood, and pus in the stool may be reported by patients if the colon is involved. Involvement of the small intestine usually presents with evidence of malabsorption, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and anorexia, which may be subtle early in the disease course. Anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are more common in patients with gastroduodenal involvement, whereas debilitating perirectal pain, malodorous discharge from a fistula, and disfiguring scars from active disease or previous surgery may be present in patients with perianal disease. Patients may also present with symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction, or with anemia, recurrent fistulas, or fever.

As stated in guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), multiple streams of information, including history and physical examination, laboratory tests, endoscopy results, pathology findings, and radiographic tests, must be incorporated to arrive at a clinical diagnosis of Crohn disease. In most cases, the presence of chronic intestinal inflammation solidifies a diagnosis of Crohn disease. However, it can be challenging to differentiate Crohn disease from ulcerative colitis, particularly when the inflammation is confined to the colon. Bleeding is much more common in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn disease, whereas intestinal obstruction is common in Crohn disease and uncommon in ulcerative colitis. Fistulae and perianal disease are common in Crohn disease but are absent or rare in ulcerative colitis. Moreover, weight loss is typical in patients with Crohn disease but is uncommon in ulcerative colitis.

Additional diagnostic clues for Crohn disease include discontinuous involvement with skip areas; sparing of the rectum; deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Only a small percentage of patients have granulomas on biopsy. The presence of ileitis in a patient with extensive colitis (ie, backwash ileitis) can also make determining the inflammatory bowel disease subtype challenging.

Arthropathy (both axial and peripheral) is a classic extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn disease, as are dermatologic manifestations (including pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum); ocular manifestations (including uveitis, scleritis, and episcleritis); and hepatobiliary disease (ie, primary sclerosing cholangitis). Less common extraintestinal complications of Crohn disease include:

• Thromboembolism (both venous and arterial)

• Metabolic bone diseases

• Osteonecrosis

• Cholelithiasis

• Nephrolithiasis.

Only 20%-30% of patients with Crohn disease will have a nonprogressive or indolent course. Clinical features that are associated with a high risk for progressive disease burden include young age at diagnosis, initial extensive bowel involvement, ileal or ileocolonic involvement, perianal or severe rectal disease, and a penetrating or stenosis disease phenotype.

According to the AGA's Clinical Care Pathway for Crohn Disease, clinical laboratory testing in a patient with symptoms of Crohn disease should include:

• Complete blood cell count (anemia and leukocytosis are the most common abnormalities seen)

• C-reactive protein (not a specific marker, but may correlate with disease activity in a subset of patients)

• Comprehensive metabolic panel

• Fecal calprotectin (may correlate with intestinal inflammation; can help distinguish inflammatory bowel disorders from irritable bowel syndrome)

• Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (may be elevated in some patients; not a specific marker)

Ileocolonoscopy with biopsies should be performed in the evaluation of patients with suspected Crohn disease, and disease distribution and severity should be documented at the time of diagnosis. Biopsies of uninvolved mucosa are recommended to identify the extent of histologic disease.

Consult the AGA guidelines for more extensive details on the workup for Crohn disease, including indications for additional imaging and phenotypic classification.

In recent years, outcomes in Crohn disease have improved, which is probably the result of earlier diagnosis, increasing use of biologics, escalation or alteration of therapy based on disease severity, and endoscopic management of colorectal cancer. As noted above, Crohn disease includes multiple phenotypes, characterized by the Montreal Classification as stricturing, penetrating, inflammatory (nonstricturing and nonpenetrating), and perianal disease. Each of these phenotypes can present with a range in severity from mild to severe disease.

In general, therapeutic recommendations for patients are based on disease location, disease severity, disease-associated complications, and future disease prognosis and are individualized according to the symptomatic response and tolerance. Current therapeutic approaches should be considered a sequential continuum to treat acute disease or induce clinical remission, then maintain response or remission. Pharmacologic options include antidiarrheal agents, anti-inflammatory therapies (eg, sulfasalazine, mesalamine), corticosteroids (a short course for severe disease), biologic therapies (eg, infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, natalizumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab), and occasionally immunosuppressive agents (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil). In addition to their 2014 guidelines on the management of Crohn disease in adults, the AGA recently released guidelines specific to the medical management of moderate to severe luminal and fistulizing Crohn disease.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

An 18-year-old man presents with increasing fatigue, prolonged diarrhea, and intermittent abdominal pain. The patient is nearly 6 months into his freshman year at the local university, where he resides. He states that his symptoms began approximately 12 weeks earlier. He describes passing an average of eight to 10 watery stools per day, including nocturnal diarrhea, with no noticeable blood or mucus and no rectal urgency. The patient has lost 13 lb since his symptoms began, which he attributes to the diarrhea and to adjusting to dormitory life and institutional meals. He also notes a slight decrease in appetite. His symptoms typically begin within an hour of awakening, after he has had his morning meal. The patient admits to smoking and occasional use of cannabis. He is not taking any medications or over-the-counter products.

Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 120/70 mm Hg, pulse of 74 beats/min, and temperature of 98.4 °F (37 °C). His weight is 139 lb and his height is 5 ft 10 in. Diffuse abdominal tenderness is present; inspection of the perianal region and rectal examination are normal. There is a positive first-degree family history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and inflammatory bowel disease. His paternal grandmother died of colon cancer at 77 years of age and his maternal grandfather died of ischemic stroke at 82 years of age.

Laboratory findings are all within the normal range and stool testing excludes infectious etiologies. Subsequent endoscopic findings include multiple colonic ulcers longitudinally arranged with a cobblestone appearance.

Crohn Disease: Presentation and Diagnosis

Ulcerative Colitis: Presentation and Diagnosis

Boy presents with abdominal cramping

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an autoimmune-related inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It typically develops in the rectum and extends to involve the large intestine. Pediatric UC can have a more severe phenotype than adult disease and may affect a child's pubertal development, bone mineral density, nutrition levels, and social life. It is currently theorized that the age at diagnosis and sex of the patient do not predict disease activity.

UC disease can announce itself as mild, moderate, or severe, and the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) endoscopic grading is used as a clinical scoring system. The most common presenting symptoms are rectal bleeding, diarrhea, and abdominal pain; among children, the presentation can vary.

Crohns disease, another IBD, must be carefully ruled out of the differential. Colonoscopy represents the first-line approach in the diagnosis of IBD. The findings that would suggest Crohns disease are sparing of the rectal mucosa, aphthous ulceration, and noncontiguous (or skip) lesions. Micronutrient and vitamin levels are usually low in Crohns disease. And although weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are commonly seen in the context of Crohns disease, they are uncommon or rare in UC. Bleeding is observed much more frequently in UC.

During UC workup, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level often serve as markers of disease activity. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) test is frequently used with suspected UC (though this measure may not correlate with disease activity). In addition, a broad metabolic panel should be performed, along with stool cultures, to rule out infection.

The goals of pediatric UC management are to maintain control of the disease, extend periods of remission, and reduce long-term damage caused by inflammation, all while potentially allowing the patient to function as normally as possible. Anti-inflammatory therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid agents, such as sulfasalazine and mesalamine, is foundational to treatment. Acute flares of UC in the pediatric population are usually responsive to corticosteroids, but these regimens should be short-term only. Immunomodulatory agents, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and newer therapies such as monoclonal antibodies are also used during flares, but only a minority of patients will require these therapies. These are also considered treatment alternatives for patients who are steroid-dependent or steroid-refractory.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships

A 5-year-old boy presents with abdominal cramping and bloody stools over the course of 2 days. His mother explains that the onset of diarrhea was insidious. Because the patient has a sensitive stomach, she tries to keep his diet relatively bland, but she worries about what he eats at school. He is slightly underweight for his age group. The family has not traveled recently. The patient does not have a fever, but skin turgor is decreased. There is no evidence of fistulae or abscesses. His complete blood cell count is 10.6 g/dL.