User login

Agitation and emotional lability

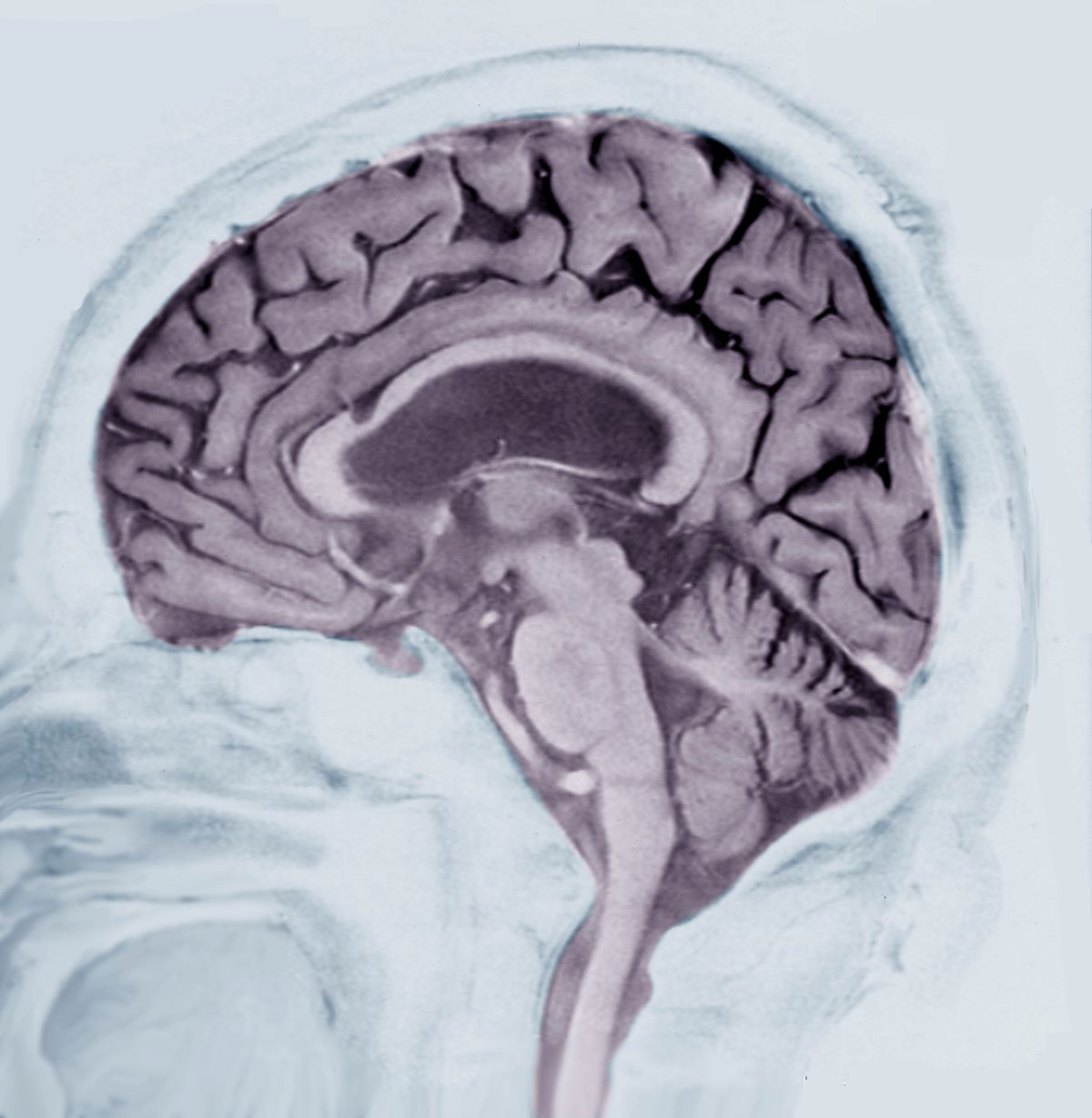

This patient’s presentation is indicative of moderate-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is confirmed by physical exam and testing; most notably, her MMSE score of 18 (a score of ≥ 25 is considered normal) and MRI results showing distinct cortical atrophy. At this stage of disease, signs and symptoms become more pronounced and widespread to include not only language deficiencies, prominent memory loss, and sensory processing, but also motor deficits and behavioral issues, all of which are clearly present in this patient.

A very important clinical consideration is a possible delay in diagnosis. It is atypical for an initial diagnosis of AD to be made when a patient is in the moderate stage of disease. This patient’s history over 5 years before her diagnosis included complaints of forgetfulness and low-level dyspraxia, which were not pursued. Reasons for this can vary. Broadly, patient interactions in a primary care setting tend to be brief, thus, many patients are not engaged in their care. Early symptoms — eg, memory impairment — can be missed during routine office visits.

There are also significant racial disparities in the diagnosis of dementia. According to National Institute of Aging-funded studies that were conducted in 39 AD Research Centers, White patients > 65 years old had a significantly higher prevalence of dementia diagnoses at baseline visits than Black patients in the same age group. Black patients, especially Black women, tend not to be diagnosed with AD until it has progressed. Conversely, Black patients had more risk factors for AD, greater cognitive impairment, and more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) than those of other races and ethnicities.

Another barrier to timely diagnosis in Black patients is disparity in access to neuroimaging. In a study conducted by Wibecan and colleagues at Boston Medical Center, researchers found that among neuroimaging assessments conducted at the facility, Black patients who received MRI or CT scan for the diagnosis of cognitive impairment were older than White patients (72.5 years vs 67 years). Additionally, Black patients were significantly less likely to undergo MRI (the gold standard of care for dementia diagnosis) than CT scan.

Hypothyroidism is an endocrine disorder that occurs because of a deficiency in thyroid hormone. Symptoms tend to be subtle and non-specific but vary greatly. Some of the hallmark symptoms are fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, dry skin, and hair loss. Additionally, emotional lability and depressed mood with mental impairment, slowed speech, and movement, as evident in this patient. However, hypothyroidism was ruled out when her laboratory results returned with all values within normal range.

Vascular dementia is the second-most prevalent form of dementia after AD. It is characterized as cognitive impairment that occurs after one, or a series of, neurologic events and does not refer to a single disease but to a variety of vascular disorders. Patients with vascular dementia often exhibit mood and behavioral changes, deficits in executive function, and severe memory loss, all of which are present in this patient. However, as there were no (known) neurologic events in this patient — and no evidence thereof on imaging — and her hypertension is relatively well controlled, this is not a diagnostic consideration for this patient.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is caused by the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. It is characterized by abnormal gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. Patients with NPH experience decreased attention, significant memory loss, bradyphrenia, bradykinesia, and broad-based gait, all of which feature in this patient. However, brain MRI was negative for structural abnormalities of this type, and there was no indication of NPH, which rules it out as a potential diagnosis.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient’s presentation is indicative of moderate-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is confirmed by physical exam and testing; most notably, her MMSE score of 18 (a score of ≥ 25 is considered normal) and MRI results showing distinct cortical atrophy. At this stage of disease, signs and symptoms become more pronounced and widespread to include not only language deficiencies, prominent memory loss, and sensory processing, but also motor deficits and behavioral issues, all of which are clearly present in this patient.

A very important clinical consideration is a possible delay in diagnosis. It is atypical for an initial diagnosis of AD to be made when a patient is in the moderate stage of disease. This patient’s history over 5 years before her diagnosis included complaints of forgetfulness and low-level dyspraxia, which were not pursued. Reasons for this can vary. Broadly, patient interactions in a primary care setting tend to be brief, thus, many patients are not engaged in their care. Early symptoms — eg, memory impairment — can be missed during routine office visits.

There are also significant racial disparities in the diagnosis of dementia. According to National Institute of Aging-funded studies that were conducted in 39 AD Research Centers, White patients > 65 years old had a significantly higher prevalence of dementia diagnoses at baseline visits than Black patients in the same age group. Black patients, especially Black women, tend not to be diagnosed with AD until it has progressed. Conversely, Black patients had more risk factors for AD, greater cognitive impairment, and more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) than those of other races and ethnicities.

Another barrier to timely diagnosis in Black patients is disparity in access to neuroimaging. In a study conducted by Wibecan and colleagues at Boston Medical Center, researchers found that among neuroimaging assessments conducted at the facility, Black patients who received MRI or CT scan for the diagnosis of cognitive impairment were older than White patients (72.5 years vs 67 years). Additionally, Black patients were significantly less likely to undergo MRI (the gold standard of care for dementia diagnosis) than CT scan.

Hypothyroidism is an endocrine disorder that occurs because of a deficiency in thyroid hormone. Symptoms tend to be subtle and non-specific but vary greatly. Some of the hallmark symptoms are fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, dry skin, and hair loss. Additionally, emotional lability and depressed mood with mental impairment, slowed speech, and movement, as evident in this patient. However, hypothyroidism was ruled out when her laboratory results returned with all values within normal range.

Vascular dementia is the second-most prevalent form of dementia after AD. It is characterized as cognitive impairment that occurs after one, or a series of, neurologic events and does not refer to a single disease but to a variety of vascular disorders. Patients with vascular dementia often exhibit mood and behavioral changes, deficits in executive function, and severe memory loss, all of which are present in this patient. However, as there were no (known) neurologic events in this patient — and no evidence thereof on imaging — and her hypertension is relatively well controlled, this is not a diagnostic consideration for this patient.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is caused by the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. It is characterized by abnormal gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. Patients with NPH experience decreased attention, significant memory loss, bradyphrenia, bradykinesia, and broad-based gait, all of which feature in this patient. However, brain MRI was negative for structural abnormalities of this type, and there was no indication of NPH, which rules it out as a potential diagnosis.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient’s presentation is indicative of moderate-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is confirmed by physical exam and testing; most notably, her MMSE score of 18 (a score of ≥ 25 is considered normal) and MRI results showing distinct cortical atrophy. At this stage of disease, signs and symptoms become more pronounced and widespread to include not only language deficiencies, prominent memory loss, and sensory processing, but also motor deficits and behavioral issues, all of which are clearly present in this patient.

A very important clinical consideration is a possible delay in diagnosis. It is atypical for an initial diagnosis of AD to be made when a patient is in the moderate stage of disease. This patient’s history over 5 years before her diagnosis included complaints of forgetfulness and low-level dyspraxia, which were not pursued. Reasons for this can vary. Broadly, patient interactions in a primary care setting tend to be brief, thus, many patients are not engaged in their care. Early symptoms — eg, memory impairment — can be missed during routine office visits.

There are also significant racial disparities in the diagnosis of dementia. According to National Institute of Aging-funded studies that were conducted in 39 AD Research Centers, White patients > 65 years old had a significantly higher prevalence of dementia diagnoses at baseline visits than Black patients in the same age group. Black patients, especially Black women, tend not to be diagnosed with AD until it has progressed. Conversely, Black patients had more risk factors for AD, greater cognitive impairment, and more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) than those of other races and ethnicities.

Another barrier to timely diagnosis in Black patients is disparity in access to neuroimaging. In a study conducted by Wibecan and colleagues at Boston Medical Center, researchers found that among neuroimaging assessments conducted at the facility, Black patients who received MRI or CT scan for the diagnosis of cognitive impairment were older than White patients (72.5 years vs 67 years). Additionally, Black patients were significantly less likely to undergo MRI (the gold standard of care for dementia diagnosis) than CT scan.

Hypothyroidism is an endocrine disorder that occurs because of a deficiency in thyroid hormone. Symptoms tend to be subtle and non-specific but vary greatly. Some of the hallmark symptoms are fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, dry skin, and hair loss. Additionally, emotional lability and depressed mood with mental impairment, slowed speech, and movement, as evident in this patient. However, hypothyroidism was ruled out when her laboratory results returned with all values within normal range.

Vascular dementia is the second-most prevalent form of dementia after AD. It is characterized as cognitive impairment that occurs after one, or a series of, neurologic events and does not refer to a single disease but to a variety of vascular disorders. Patients with vascular dementia often exhibit mood and behavioral changes, deficits in executive function, and severe memory loss, all of which are present in this patient. However, as there were no (known) neurologic events in this patient — and no evidence thereof on imaging — and her hypertension is relatively well controlled, this is not a diagnostic consideration for this patient.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is caused by the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. It is characterized by abnormal gait, dementia, and urinary incontinence. Patients with NPH experience decreased attention, significant memory loss, bradyphrenia, bradykinesia, and broad-based gait, all of which feature in this patient. However, brain MRI was negative for structural abnormalities of this type, and there was no indication of NPH, which rules it out as a potential diagnosis.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 76-year-old Black woman presents to her physician. She is accompanied by her daughter who reports that, over the last 9 months, her mother has exhibited worsening memory loss, confusion, impaired judgment, agitation, and emotional lability. She is often unaware of where she is or how she got there. She sometimes does not recognize her family members or people who are familiar to her. Her appetite has been variable, and her sleep schedule is altered so that she often sleeps during the day and is awake at night. Sometimes, she is so irritable that she becomes aggressive and insists on situations that don’t exist. Her executive function is low. Her daughter reports that the patient had a fall 9 months ago and again 4 months ago, after which her symptoms became progressively worse.

The patient has complained about being forgetful and clumsy for much of the past 5 years, which she has attributed to old age. Until the last year or so, these have not greatly impaired her daily function and were not of great concern to her family or providers. She has a history of hypertension and diabetes, both of which are pharmacologically managed with mixed results due to variable adherence.

Physical exam confirms her daughter’s report. The patient appears thin, fatigued, and anxious. She has lost 20 lb since her last visit. She has great difficulty maintaining focus on what is being asked of her and in following the conversation. When she does speak, her speech is slow. She exhibits both motor deficits — in balance and coordination — and a bradykinetic gait.

Laboratory testing is performed: complete blood count w/diff, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid panel, cobalamin level, vitamin D screening. All results are within normal range for this patient. She was unable to complete the Geriatric Depression Scale on her own; direct questioning about whether she was feeling depressed is negative. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score is 18. MRI is performed; sagittal view reveals cortical atrophy.

Alzheimer's Disease Signs and Symptoms

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Fatigue and brain fog

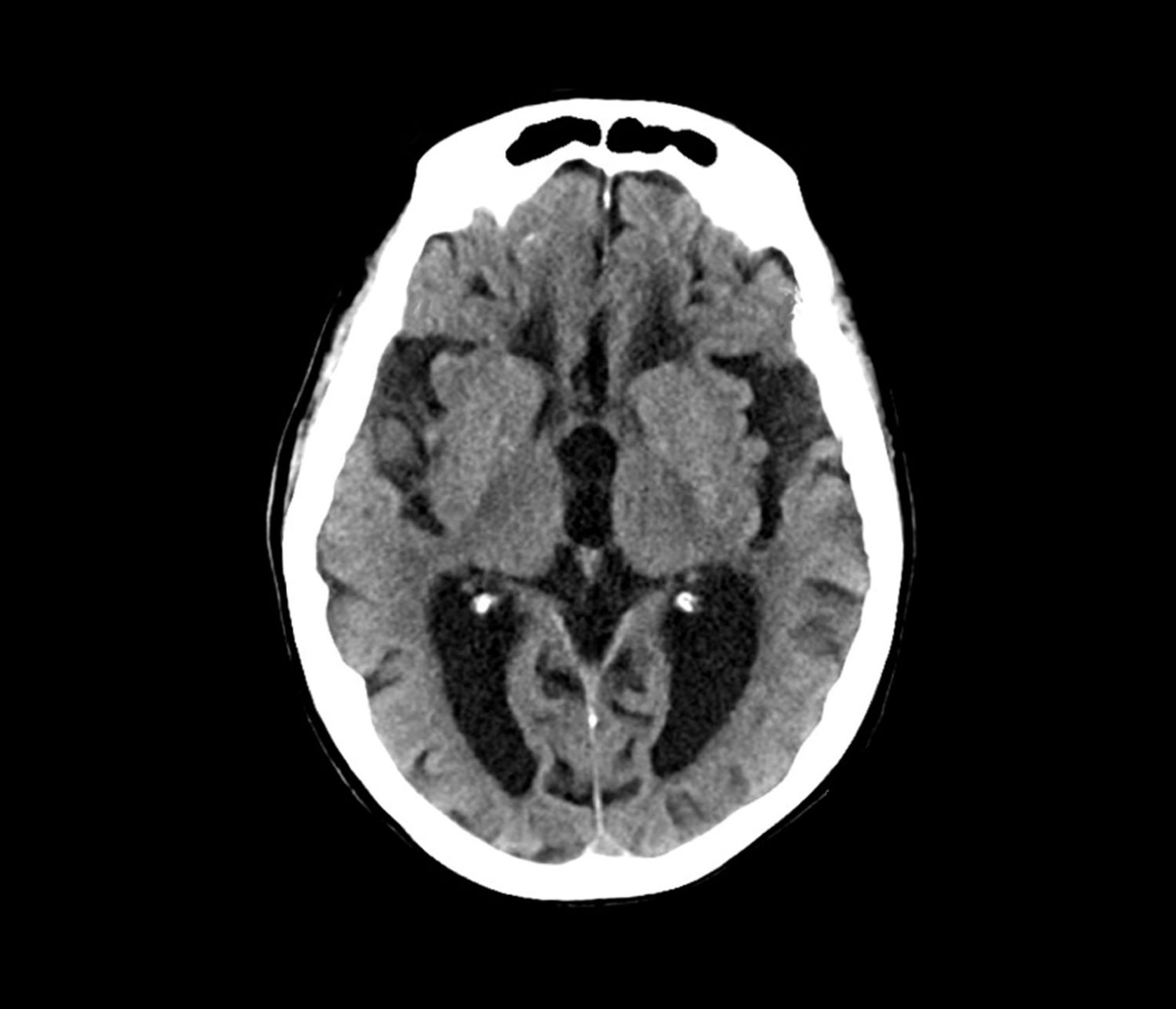

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 52-year-old female presents complaining of fatigue, brain fog, and headaches. She reports that, over the last year, she feels increasingly more irritable, anxious, overwhelmed, and sometimes disoriented. When prompted, she admits to having trouble keeping track of things — dates, important deadlines, objects like her keys, and things she uses each day. She needs multiple reminder events or tasks and must write everything down. She also reports that she often loses her train of thought and sometimes struggles to find words. She works in a medical office, is married, and has two children in college. She helps with caring for her in-laws on the weekend by doing their bills and grocery shopping. She admits to being moody and does not want to socialize, which she attributes to fatigue and having a busy life. She also complains of muscle stiffness and general clumsiness. Eight months ago, the patient was in an automobile accident in which her car was totaled, but she did not sustain serious injury and opted not to seek medical evaluation.

Physical exam reveals slight visuospatial dysfunction, with issues with both coordination and balance. The patient appears fatigued and has some trouble maintaining her attention during the conversation. Further questioning reveals mild anomic aphasia and some lapses in recent memory. Her reflexes are otherwise normal, as are heart, lung, and breath sounds. All systemic lymph nodes are normal as are liver and spleen on palpation. The patient recently discovered that her estranged father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at 58 years of age and passed away 5 years later.

Laboratory testing is performed and reveals nothing remarkable. Considering the car accident and new cognitive/behavioral changes experienced by the patient, a CT of the brain is ordered. Results are negative for concussion and cerebral hemorrhage but show cortical atrophy of the temporal territories and a large increase in the size of the subarachnoid spaces predominantly affecting the parietal region.

Alzheimer's Disease and Athletes

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Progressive cognitive decline

Individuals with DS are at significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) because of the overexpression of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21.

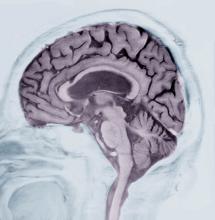

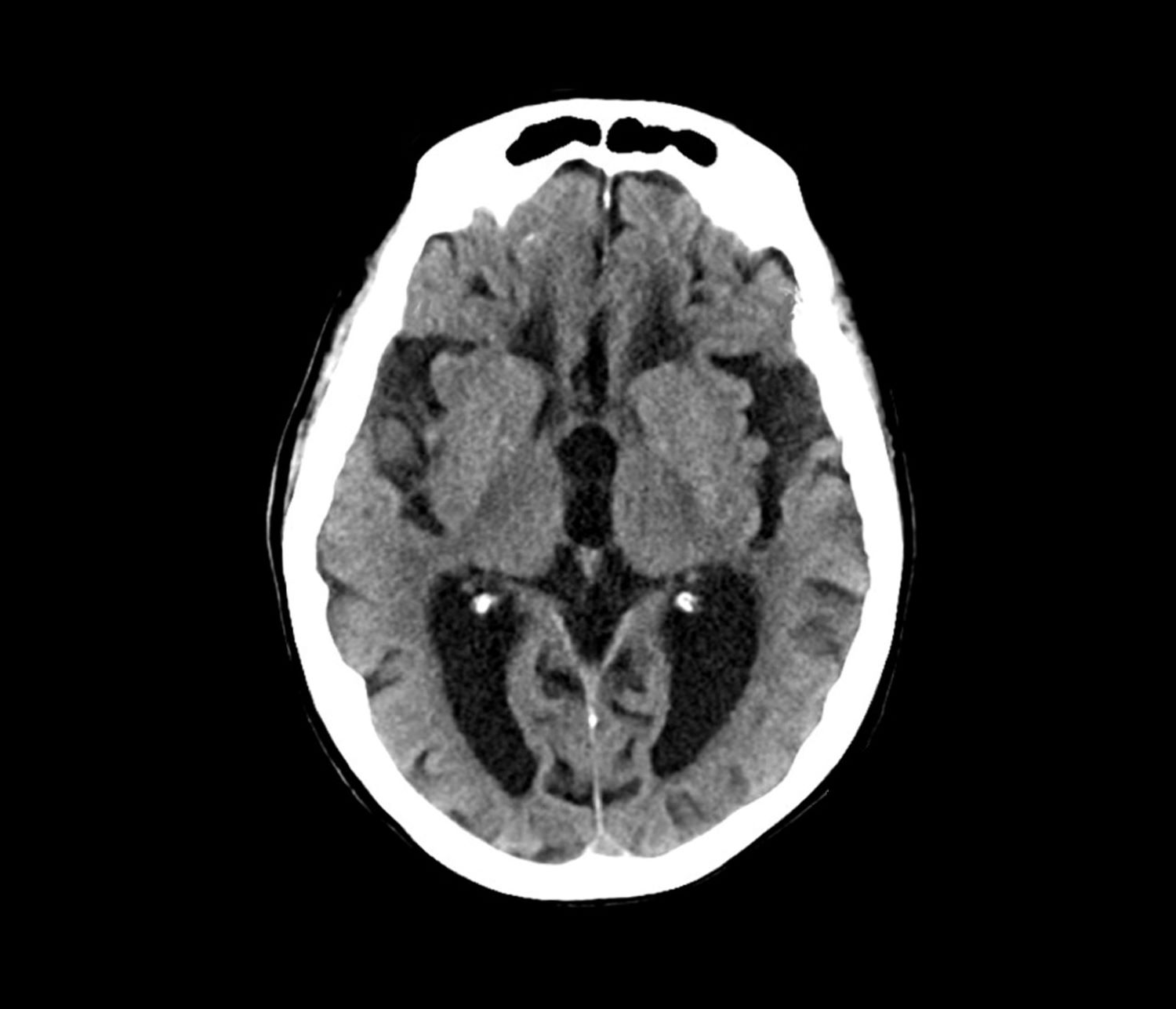

The patient exhibits hallmark symptoms of AD, including progressive memory loss, disorientation, difficulty performing daily tasks, and behavioral changes such as irritability and social withdrawal. The MRI findings of ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy are consistent with brain changes commonly seen in AD, particularly in individuals with DS who often develop these changes earlier in life (typically in their thirties or forties).

Frontotemporal dementia primarily causes behavioral and language changes with relative memory sparing early on, making it inconsistent with this patient's prominent memory loss, disorientation, and generalized cortical atrophy — features more typical of AD.

Vascular dementia often presents with stepwise decline and focal neurologic deficits; it is unlikely in this patient, given the absence of cerebrovascular events or risk factors like hypertension or diabetes.

While normal pressure hydrocephalus can cause ventricular enlargement, its classic triad of gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and dementia is incomplete here, making this answer unlikely.

DS is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, occurring in approximately 1 in 700 live births worldwide. Nearly all adults with DS develop neuropathologic changes associated with AD by age 40, and the lifetime risk of developing dementia exceeds 90%; by the age of 55-60, at least 70% of individuals with DS exhibit clinical signs of dementia.

The link between DS and neurodegeneration is largely attributed to the triplication of chromosome 21, which includes the APP gene. Overexpression of APP leads to excessive production and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), which forms the hallmark plaques seen in AD. In DS, amyloid plaques begin to form as early as the teenage years, and by the fourth decade, neurofibrillary tangles (tau protein aggregates) and widespread neurodegeneration are nearly universal.

Initial symptoms of AD often include memory impairment, particularly short-term memory deficits, and executive dysfunction, difficulty with planning and problem-solving, and visuospatial deficits. Behavioral and personality changes, such as irritability, withdrawal, or apathy, are also commonly reported. Compared with sporadic AD, individuals with DS often show earlier behavioral symptoms, including impulsivity and changes in social interactions, which may precede noticeable memory deficits. Additionally, late-onset myoclonic epilepsy is common in individuals with DS and dementia, further complicating diagnosis and care.

The diagnosis of dementia in DS is challenging because of baseline intellectual disability, which makes it difficult to assess cognitive decline using standard neuropsychological tests. However, a combination of clinical history, caregiver reports, neuroimaging, and biomarker analysis can aid in early detection. Structural MRI of the brain often reveals ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy, while PET imaging can detect early amyloid and tau accumulation.

Because AD is now the leading cause of death in individuals with DS, the lack of effective disease-modifying treatments highlights an important need for clinical trials focused on this population. Current research aims to explore the role of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies, neuroprotective agents, and lifestyle interventions to delay or prevent neurodegeneration.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Individuals with DS are at significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) because of the overexpression of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21.

The patient exhibits hallmark symptoms of AD, including progressive memory loss, disorientation, difficulty performing daily tasks, and behavioral changes such as irritability and social withdrawal. The MRI findings of ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy are consistent with brain changes commonly seen in AD, particularly in individuals with DS who often develop these changes earlier in life (typically in their thirties or forties).

Frontotemporal dementia primarily causes behavioral and language changes with relative memory sparing early on, making it inconsistent with this patient's prominent memory loss, disorientation, and generalized cortical atrophy — features more typical of AD.

Vascular dementia often presents with stepwise decline and focal neurologic deficits; it is unlikely in this patient, given the absence of cerebrovascular events or risk factors like hypertension or diabetes.

While normal pressure hydrocephalus can cause ventricular enlargement, its classic triad of gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and dementia is incomplete here, making this answer unlikely.

DS is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, occurring in approximately 1 in 700 live births worldwide. Nearly all adults with DS develop neuropathologic changes associated with AD by age 40, and the lifetime risk of developing dementia exceeds 90%; by the age of 55-60, at least 70% of individuals with DS exhibit clinical signs of dementia.

The link between DS and neurodegeneration is largely attributed to the triplication of chromosome 21, which includes the APP gene. Overexpression of APP leads to excessive production and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), which forms the hallmark plaques seen in AD. In DS, amyloid plaques begin to form as early as the teenage years, and by the fourth decade, neurofibrillary tangles (tau protein aggregates) and widespread neurodegeneration are nearly universal.

Initial symptoms of AD often include memory impairment, particularly short-term memory deficits, and executive dysfunction, difficulty with planning and problem-solving, and visuospatial deficits. Behavioral and personality changes, such as irritability, withdrawal, or apathy, are also commonly reported. Compared with sporadic AD, individuals with DS often show earlier behavioral symptoms, including impulsivity and changes in social interactions, which may precede noticeable memory deficits. Additionally, late-onset myoclonic epilepsy is common in individuals with DS and dementia, further complicating diagnosis and care.

The diagnosis of dementia in DS is challenging because of baseline intellectual disability, which makes it difficult to assess cognitive decline using standard neuropsychological tests. However, a combination of clinical history, caregiver reports, neuroimaging, and biomarker analysis can aid in early detection. Structural MRI of the brain often reveals ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy, while PET imaging can detect early amyloid and tau accumulation.

Because AD is now the leading cause of death in individuals with DS, the lack of effective disease-modifying treatments highlights an important need for clinical trials focused on this population. Current research aims to explore the role of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies, neuroprotective agents, and lifestyle interventions to delay or prevent neurodegeneration.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Individuals with DS are at significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) because of the overexpression of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21.

The patient exhibits hallmark symptoms of AD, including progressive memory loss, disorientation, difficulty performing daily tasks, and behavioral changes such as irritability and social withdrawal. The MRI findings of ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy are consistent with brain changes commonly seen in AD, particularly in individuals with DS who often develop these changes earlier in life (typically in their thirties or forties).

Frontotemporal dementia primarily causes behavioral and language changes with relative memory sparing early on, making it inconsistent with this patient's prominent memory loss, disorientation, and generalized cortical atrophy — features more typical of AD.

Vascular dementia often presents with stepwise decline and focal neurologic deficits; it is unlikely in this patient, given the absence of cerebrovascular events or risk factors like hypertension or diabetes.

While normal pressure hydrocephalus can cause ventricular enlargement, its classic triad of gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and dementia is incomplete here, making this answer unlikely.

DS is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, occurring in approximately 1 in 700 live births worldwide. Nearly all adults with DS develop neuropathologic changes associated with AD by age 40, and the lifetime risk of developing dementia exceeds 90%; by the age of 55-60, at least 70% of individuals with DS exhibit clinical signs of dementia.

The link between DS and neurodegeneration is largely attributed to the triplication of chromosome 21, which includes the APP gene. Overexpression of APP leads to excessive production and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ), which forms the hallmark plaques seen in AD. In DS, amyloid plaques begin to form as early as the teenage years, and by the fourth decade, neurofibrillary tangles (tau protein aggregates) and widespread neurodegeneration are nearly universal.

Initial symptoms of AD often include memory impairment, particularly short-term memory deficits, and executive dysfunction, difficulty with planning and problem-solving, and visuospatial deficits. Behavioral and personality changes, such as irritability, withdrawal, or apathy, are also commonly reported. Compared with sporadic AD, individuals with DS often show earlier behavioral symptoms, including impulsivity and changes in social interactions, which may precede noticeable memory deficits. Additionally, late-onset myoclonic epilepsy is common in individuals with DS and dementia, further complicating diagnosis and care.

The diagnosis of dementia in DS is challenging because of baseline intellectual disability, which makes it difficult to assess cognitive decline using standard neuropsychological tests. However, a combination of clinical history, caregiver reports, neuroimaging, and biomarker analysis can aid in early detection. Structural MRI of the brain often reveals ventricular enlargement and cortical atrophy, while PET imaging can detect early amyloid and tau accumulation.

Because AD is now the leading cause of death in individuals with DS, the lack of effective disease-modifying treatments highlights an important need for clinical trials focused on this population. Current research aims to explore the role of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies, neuroprotective agents, and lifestyle interventions to delay or prevent neurodegeneration.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 40-year-old man with Down syndrome (DS) presented with progressive cognitive decline over 2 years, characterized by memory impairment, difficulty performing familiar tasks, and increasing disorientation. His caregivers noted mood changes, including irritability and withdrawal, and occasional episodes of agitation. Clinical history revealed congenital heart disease (surgically repaired in childhood) and hypothyroidism, which was well controlled with levothyroxine. Physical examination showed no focal neurologic deficits, but he exhibited mild hypotonia, a characteristic feature of DS, and a shuffling gait. Routine blood tests revealed normal thyroid function, no evidence of vitamin B12 deficiency, and unremarkable metabolic panels. An MRI scan (as shown in the image) demonstrated marked ventricular enlargement and generalized cortical atrophy.

Alzheimer's Disease & Down Syndrome

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.