User login

How to talk to patients and families about brain stimulation

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

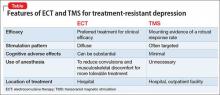

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

Brain stimulation often is used for treatment-resistant depression when medications and psychotherapy are not enough to elicit a meaningful response. It is both old and new again: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been used for decades, while emerging technologies, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are gaining acceptance.

Patients and families often arrive at the office with fears and assumptions about these types of treatments, which should be discussed openly. There are also differences between these treatment approaches that can be discussed (Table).

Electroconvulsive therapy

Although ECT has been shown to be the most efficacious treatment for treatment-resistant depression,1 the most common response from patients and families that I hear when discussing ECT use is, “Do you really still do that?” Many patients and family members associate this treatment with mass media portrayals over the past several decades, such as the motion picture One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which paired inhumane and unnecessary use of ECT with a frontal lobotomy, thereby associating this treatment with something inherently unethical.

My approach to discussing ECT with patients and families is to convey these main points:

- Consensual. In most cases, ECT is performed with the explicit informed consent of the patient, and is not done against the patient’s will.

- Effective. ECT has a remission rate of 75% after the first 2 weeks of use in patients suffering from acute depressive illnesses.2

- Safe. ECT protocols have evolved to maximize efficacy while minimizing adverse effects. Advances in anesthesia use with paralytic agents and anti-inflammatory medications reduce convulsions and subsequent musculoskeletal discomfort.

In addition, I note that:

- Ultra-brief stimulation parameters often are used to minimize cognitive side effects.

- ECT is associated with some psychosocial limitations, including being unable to drive during acute treatment and requiring supervision for several hours after sessions.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

The field of non-invasive brain stimulation—in particular, TMS—faces a different set of complex issues to navigate. Because TMS is relatively new (approved by the FDA in 2008 for treatment-resistant depression),3 patients and families might believe that TMS may be more effective than ECT, which has not been demonstrated.4 It is important to communicate that:

- Although TMS is a FDA-approved treatment that has helped many patients with treatment-resistant depression, ECT remains the clinical treatment of choice for severe depression.

- Among antidepressant non-responders who had stopped all other antidepressant treatment, 44% of those who received deep TMS responded to treatment after 16 weeks, compared with 26% who received sham treatment.5

- Most patients usually require TMS for 4 to 6 weeks, 5 days a week, before beginning a taper phase.

- TMS has few side effects (headache being the most common); serious adverse effects (seizures, mania) have been reported but are rare.3

- Patients usually are able to continue their daily life and other outpatient treatments without the restrictions often placed on patients receiving ECT.

- If the patient responded to ECT in the past but could not tolerate adverse cognitive effects, TMS might be a better choice than other treatments.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.

1. Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Pini S, et al. Efficacy of ECT in depression: a meta-analytic review. J ECT. 2004;20(1):13-20.

2. Husain MM, Rush AJ, Fink M, et al. Speed of response and remission in major depressive disorder with acute electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): a Consortium for Research in ECT (CORE) report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):485-491.

3. Stern AP, Cohen D. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry. 2013;3(1):107-115.

4. Micallef-Trigona B. Comparing the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2014;2014:135049. doi: 10.1155/2014/135049.

5. Levkovitz Y, Isserles M, Padberg F. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective, multi-center, randomized, controlled trial. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):64-73.