User login

Four questions address stigma

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

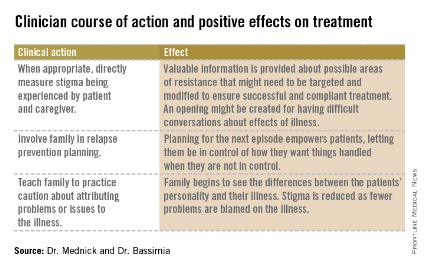

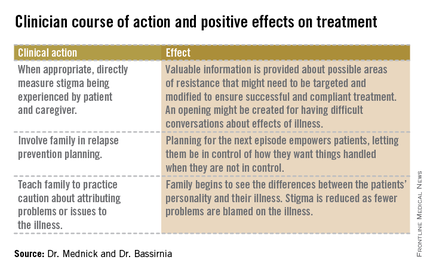

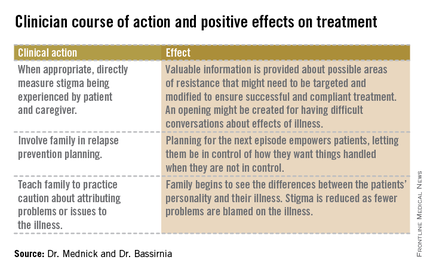

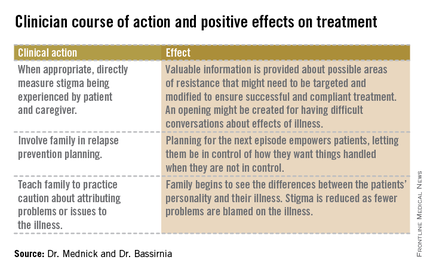

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.

The essential role of family in treating bipolar disorder

Kevin was doing very well in law school, until he showed up at his professor’s house in the middle of the night. Normally a thoughtful, quiet, introverted young man, Kevin was hardly recognizable to his professor, who found him outside yelling loudly and demanding to speak about an underground conspiracy he believed he had uncovered. He had always been a good student, and his family was very proud of his accomplishments up until now. At the age of 24, Kevin’s first manic episode was triggered by late nights studying for his law school exams and marijuana use to cope with stress.

Police responded to noise complaints, and Kevin was hospitalized. The manic episode resolved surprisingly quickly in the absence of marijuana use and with the help of an atypical antipsychotic. The patient’s intelligence and articulate lawyer-in-training charm made his inpatient doctors hard pressed to justify an extended hospital stay, and he was discharged 3 days later with a prescription and instructions for follow-up. He promptly discarded both.

When his next manic episode arose, Kevin disappeared for 2 weeks, and after fearing the worst, Kevin’s family was relieved to receive a call from Kevin’s aunt, who lived across the country and had just found him at her doorstep. This time, without the involvement of law enforcement, there seemed to be no way for Kevin’s mother, father, older sister, and aunt to persuade Kevin to enter the hospital or to take medications. Kevin’s aunt accompanied him on a plane home, and in the face of Kevin’s unwillingness to enter treatment alone, they decided to enter treatment as a family.

Predictors of episodes

The strongest predictors of future episodes and poor outcome in patients with bipolar disorder are a greater number of previous episodes, shorter intervals between episodes, a history of psychosis, a history of anxiety, persistence of affective symptoms and episodes, and stressful life events. Some evidence has suggested that poor job functioning, lack of social support, increased expressed emotion in the family, and introverted or obsessional personality traits all might predict poor outcome in bipolar disorder (J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006;12:269-82).

An overwhelmingly emotional home environment can make a large contribution to relapse. Multiple studies have shown that a high level of "expressed emotion" (characterized by overinvolvement and excessive criticism) predicts patient relapse independent of medication compliance, baseline symptoms, and demographics (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988;45:225-31)

Because bipolar disorder is an unpredictable, potentially destructive illness, it is important to grab any factors that we and our patients might have control over and do our best to modify them positively. With this in mind, the Family Focused Treatment (FFT) model was developed, with the philosophy that by keeping patients well informed about the facts and realities of the disorder and working on the communication and coping mechanisms operating within the family, relapse prevention and emotional stability will be better maintained. In this way, the predictive factors of stressful life events, poor social support, and family-expressed emotion can be modified. FFT is a time limited (usually 12 sessions), highly effective treatment modality.

The principles of FFT were adapted into an ongoing-treatment model that can be implemented in a community setting, termed Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) and used by the Family Center for Bipolar in New York City, for example. FIT consists of an engagement period at the initiation of treatment, focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choosing.

After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment. Other modalities such as individual therapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy are used according to the clinician’s judgment.

This form of treatment is innovative in that it treats bipolar illness just like any other chronic illness. It promotes open communication between families of patients with bipolar disorder and the patients themselves with regard to symptoms and medications. In this way patients are not isolated from their families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician as they would do if somebody in the family had Alzheimer’s disease or diabetes.

It has been reported that up to 46% of the caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder report depression, and up to 32.4% report use of mental health services. These symptoms tend to be dependent on the nature of the caregiving relationship, suggesting that specialized interventions addressing the psychiatric needs of bipolar families might result in improved outcomes for both patients and their family members, in addition to decreases in health care costs (J. Affect. Disord. 2010;121:10-21).

Together with therapy and medication management, clinicians working in the FIT model strive to create an environment that minimizes, as much as possible, the impact of bipolar disorder on the affected individuals and their close loved ones.

Many studies have confirmed the efficacy of various psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder (J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;7:482-92; J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006;67 [suppl. 11]:28-33; J. Affect. Disord. 2007;98:11-27), and there has been a push for the integration of psychosocial treatment with pharmacotherapy, as the latter is less often sufficient on its own in preventing relapse.

Patient, family begin journey

Kevin and his family entered into family treatment. They started off with the psychoeducation portion of the treatment, and many of the myths and misinformation that they had held about bipolar disorder were dispelled. Even Kevin was able to engage in the information exchange, which he initially approached from an academic, impersonal vantage point. The communication skills phase proved more problematic as it became more personal, but still, the focus was on the family’s communication and not on Kevin as a psychiatric patient, so he responded well.

It was uncovered that Kevin’s father has always been highly critical, and Kevin’s mother tends to overprotect her children to compensate. They were taught new skills to express their feelings toward one another, and especially toward Kevin, in more productive and positive ways. In addition, they got a chance to practice those skills in subsequent sessions.

The modules continued in this vein until the family portion of treatment had completed. By this time, Kevin had developed a good rapport with his clinician, and he continued treatment despite his persistent reservations about accepting his illness. The family environment improved, and though Kevin was only sporadically compliant with his medication, the reduced stress at home and improved coping skills drove him less often to use marijuana for "self-medication," which decreased his manic episodes.

Kevin’s family periodically rejoined him in treatment sessions at predefined intervals, to check in and assess his and their progress. They were comfortable speaking with Kevin’s doctor and would call when they noticed any of the warning signs that they had collaboratively determined as markers of upcoming mania. In this way, they were all effective at keeping Kevin’s moods stable and keeping him out of the hospital.

The psychiatrist in routine practice might neither follow a manualized algorithm for family treatment nor have the time or resources at her disposal to provide a full "curriculum." Still, she can have the same success in engaging a family in understanding their loved one’s illness and contributing to the family member’s stability.

Objectives for family-focused treatment

The following objectives are adapted from "Bipolar Disorder: A Family-Focused Treatment Approach," 2nd ed. (New York: The Guilford Press, 2010):

• Encourage the patient and the family to admit that there is a vulnerability to future episodes by educating them about the natural course, progression, and chronic nature of bipolar disorder.

• Enable the patient and the family to recognize that medications are important for controlling symptoms. Provide concrete evidence for the importance and efficacy of medications and the risks of discontinuation. Explore reasons for resisting medications, including fears about becoming dependent.

• Help the patient and the family see the differences between the patient’s personality and his/her illness. Make a list of the patient’s positive attributes and a separate list of warning signs of mania. Frequently reinforce the distinction between the two.

• Assist the patient and the family in dealing with stressors that might cause a recurrence and help them rebuild family relationship ruptures after an episode. Suggest methods for positive, constructive communication such as active listening (nodding, making eye contact, paraphrasing, asking relevant questions) and expressing positive feelings toward a family member related to a specific example of a behavior.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013). Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City.

Kevin was doing very well in law school, until he showed up at his professor’s house in the middle of the night. Normally a thoughtful, quiet, introverted young man, Kevin was hardly recognizable to his professor, who found him outside yelling loudly and demanding to speak about an underground conspiracy he believed he had uncovered. He had always been a good student, and his family was very proud of his accomplishments up until now. At the age of 24, Kevin’s first manic episode was triggered by late nights studying for his law school exams and marijuana use to cope with stress.

Police responded to noise complaints, and Kevin was hospitalized. The manic episode resolved surprisingly quickly in the absence of marijuana use and with the help of an atypical antipsychotic. The patient’s intelligence and articulate lawyer-in-training charm made his inpatient doctors hard pressed to justify an extended hospital stay, and he was discharged 3 days later with a prescription and instructions for follow-up. He promptly discarded both.

When his next manic episode arose, Kevin disappeared for 2 weeks, and after fearing the worst, Kevin’s family was relieved to receive a call from Kevin’s aunt, who lived across the country and had just found him at her doorstep. This time, without the involvement of law enforcement, there seemed to be no way for Kevin’s mother, father, older sister, and aunt to persuade Kevin to enter the hospital or to take medications. Kevin’s aunt accompanied him on a plane home, and in the face of Kevin’s unwillingness to enter treatment alone, they decided to enter treatment as a family.

Predictors of episodes

The strongest predictors of future episodes and poor outcome in patients with bipolar disorder are a greater number of previous episodes, shorter intervals between episodes, a history of psychosis, a history of anxiety, persistence of affective symptoms and episodes, and stressful life events. Some evidence has suggested that poor job functioning, lack of social support, increased expressed emotion in the family, and introverted or obsessional personality traits all might predict poor outcome in bipolar disorder (J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006;12:269-82).

An overwhelmingly emotional home environment can make a large contribution to relapse. Multiple studies have shown that a high level of "expressed emotion" (characterized by overinvolvement and excessive criticism) predicts patient relapse independent of medication compliance, baseline symptoms, and demographics (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988;45:225-31)

Because bipolar disorder is an unpredictable, potentially destructive illness, it is important to grab any factors that we and our patients might have control over and do our best to modify them positively. With this in mind, the Family Focused Treatment (FFT) model was developed, with the philosophy that by keeping patients well informed about the facts and realities of the disorder and working on the communication and coping mechanisms operating within the family, relapse prevention and emotional stability will be better maintained. In this way, the predictive factors of stressful life events, poor social support, and family-expressed emotion can be modified. FFT is a time limited (usually 12 sessions), highly effective treatment modality.

The principles of FFT were adapted into an ongoing-treatment model that can be implemented in a community setting, termed Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) and used by the Family Center for Bipolar in New York City, for example. FIT consists of an engagement period at the initiation of treatment, focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choosing.

After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment. Other modalities such as individual therapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy are used according to the clinician’s judgment.

This form of treatment is innovative in that it treats bipolar illness just like any other chronic illness. It promotes open communication between families of patients with bipolar disorder and the patients themselves with regard to symptoms and medications. In this way patients are not isolated from their families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician as they would do if somebody in the family had Alzheimer’s disease or diabetes.

It has been reported that up to 46% of the caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder report depression, and up to 32.4% report use of mental health services. These symptoms tend to be dependent on the nature of the caregiving relationship, suggesting that specialized interventions addressing the psychiatric needs of bipolar families might result in improved outcomes for both patients and their family members, in addition to decreases in health care costs (J. Affect. Disord. 2010;121:10-21).

Together with therapy and medication management, clinicians working in the FIT model strive to create an environment that minimizes, as much as possible, the impact of bipolar disorder on the affected individuals and their close loved ones.

Many studies have confirmed the efficacy of various psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder (J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;7:482-92; J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006;67 [suppl. 11]:28-33; J. Affect. Disord. 2007;98:11-27), and there has been a push for the integration of psychosocial treatment with pharmacotherapy, as the latter is less often sufficient on its own in preventing relapse.

Patient, family begin journey

Kevin and his family entered into family treatment. They started off with the psychoeducation portion of the treatment, and many of the myths and misinformation that they had held about bipolar disorder were dispelled. Even Kevin was able to engage in the information exchange, which he initially approached from an academic, impersonal vantage point. The communication skills phase proved more problematic as it became more personal, but still, the focus was on the family’s communication and not on Kevin as a psychiatric patient, so he responded well.

It was uncovered that Kevin’s father has always been highly critical, and Kevin’s mother tends to overprotect her children to compensate. They were taught new skills to express their feelings toward one another, and especially toward Kevin, in more productive and positive ways. In addition, they got a chance to practice those skills in subsequent sessions.

The modules continued in this vein until the family portion of treatment had completed. By this time, Kevin had developed a good rapport with his clinician, and he continued treatment despite his persistent reservations about accepting his illness. The family environment improved, and though Kevin was only sporadically compliant with his medication, the reduced stress at home and improved coping skills drove him less often to use marijuana for "self-medication," which decreased his manic episodes.

Kevin’s family periodically rejoined him in treatment sessions at predefined intervals, to check in and assess his and their progress. They were comfortable speaking with Kevin’s doctor and would call when they noticed any of the warning signs that they had collaboratively determined as markers of upcoming mania. In this way, they were all effective at keeping Kevin’s moods stable and keeping him out of the hospital.

The psychiatrist in routine practice might neither follow a manualized algorithm for family treatment nor have the time or resources at her disposal to provide a full "curriculum." Still, she can have the same success in engaging a family in understanding their loved one’s illness and contributing to the family member’s stability.

Objectives for family-focused treatment

The following objectives are adapted from "Bipolar Disorder: A Family-Focused Treatment Approach," 2nd ed. (New York: The Guilford Press, 2010):

• Encourage the patient and the family to admit that there is a vulnerability to future episodes by educating them about the natural course, progression, and chronic nature of bipolar disorder.

• Enable the patient and the family to recognize that medications are important for controlling symptoms. Provide concrete evidence for the importance and efficacy of medications and the risks of discontinuation. Explore reasons for resisting medications, including fears about becoming dependent.

• Help the patient and the family see the differences between the patient’s personality and his/her illness. Make a list of the patient’s positive attributes and a separate list of warning signs of mania. Frequently reinforce the distinction between the two.

• Assist the patient and the family in dealing with stressors that might cause a recurrence and help them rebuild family relationship ruptures after an episode. Suggest methods for positive, constructive communication such as active listening (nodding, making eye contact, paraphrasing, asking relevant questions) and expressing positive feelings toward a family member related to a specific example of a behavior.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013). Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City.

Kevin was doing very well in law school, until he showed up at his professor’s house in the middle of the night. Normally a thoughtful, quiet, introverted young man, Kevin was hardly recognizable to his professor, who found him outside yelling loudly and demanding to speak about an underground conspiracy he believed he had uncovered. He had always been a good student, and his family was very proud of his accomplishments up until now. At the age of 24, Kevin’s first manic episode was triggered by late nights studying for his law school exams and marijuana use to cope with stress.

Police responded to noise complaints, and Kevin was hospitalized. The manic episode resolved surprisingly quickly in the absence of marijuana use and with the help of an atypical antipsychotic. The patient’s intelligence and articulate lawyer-in-training charm made his inpatient doctors hard pressed to justify an extended hospital stay, and he was discharged 3 days later with a prescription and instructions for follow-up. He promptly discarded both.

When his next manic episode arose, Kevin disappeared for 2 weeks, and after fearing the worst, Kevin’s family was relieved to receive a call from Kevin’s aunt, who lived across the country and had just found him at her doorstep. This time, without the involvement of law enforcement, there seemed to be no way for Kevin’s mother, father, older sister, and aunt to persuade Kevin to enter the hospital or to take medications. Kevin’s aunt accompanied him on a plane home, and in the face of Kevin’s unwillingness to enter treatment alone, they decided to enter treatment as a family.

Predictors of episodes

The strongest predictors of future episodes and poor outcome in patients with bipolar disorder are a greater number of previous episodes, shorter intervals between episodes, a history of psychosis, a history of anxiety, persistence of affective symptoms and episodes, and stressful life events. Some evidence has suggested that poor job functioning, lack of social support, increased expressed emotion in the family, and introverted or obsessional personality traits all might predict poor outcome in bipolar disorder (J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006;12:269-82).

An overwhelmingly emotional home environment can make a large contribution to relapse. Multiple studies have shown that a high level of "expressed emotion" (characterized by overinvolvement and excessive criticism) predicts patient relapse independent of medication compliance, baseline symptoms, and demographics (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1988;45:225-31)

Because bipolar disorder is an unpredictable, potentially destructive illness, it is important to grab any factors that we and our patients might have control over and do our best to modify them positively. With this in mind, the Family Focused Treatment (FFT) model was developed, with the philosophy that by keeping patients well informed about the facts and realities of the disorder and working on the communication and coping mechanisms operating within the family, relapse prevention and emotional stability will be better maintained. In this way, the predictive factors of stressful life events, poor social support, and family-expressed emotion can be modified. FFT is a time limited (usually 12 sessions), highly effective treatment modality.

The principles of FFT were adapted into an ongoing-treatment model that can be implemented in a community setting, termed Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) and used by the Family Center for Bipolar in New York City, for example. FIT consists of an engagement period at the initiation of treatment, focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choosing.

After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment. Other modalities such as individual therapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy are used according to the clinician’s judgment.

This form of treatment is innovative in that it treats bipolar illness just like any other chronic illness. It promotes open communication between families of patients with bipolar disorder and the patients themselves with regard to symptoms and medications. In this way patients are not isolated from their families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician as they would do if somebody in the family had Alzheimer’s disease or diabetes.

It has been reported that up to 46% of the caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder report depression, and up to 32.4% report use of mental health services. These symptoms tend to be dependent on the nature of the caregiving relationship, suggesting that specialized interventions addressing the psychiatric needs of bipolar families might result in improved outcomes for both patients and their family members, in addition to decreases in health care costs (J. Affect. Disord. 2010;121:10-21).

Together with therapy and medication management, clinicians working in the FIT model strive to create an environment that minimizes, as much as possible, the impact of bipolar disorder on the affected individuals and their close loved ones.

Many studies have confirmed the efficacy of various psychosocial treatments for bipolar disorder (J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003;7:482-92; J. Clin. Psychiatry 2006;67 [suppl. 11]:28-33; J. Affect. Disord. 2007;98:11-27), and there has been a push for the integration of psychosocial treatment with pharmacotherapy, as the latter is less often sufficient on its own in preventing relapse.

Patient, family begin journey

Kevin and his family entered into family treatment. They started off with the psychoeducation portion of the treatment, and many of the myths and misinformation that they had held about bipolar disorder were dispelled. Even Kevin was able to engage in the information exchange, which he initially approached from an academic, impersonal vantage point. The communication skills phase proved more problematic as it became more personal, but still, the focus was on the family’s communication and not on Kevin as a psychiatric patient, so he responded well.

It was uncovered that Kevin’s father has always been highly critical, and Kevin’s mother tends to overprotect her children to compensate. They were taught new skills to express their feelings toward one another, and especially toward Kevin, in more productive and positive ways. In addition, they got a chance to practice those skills in subsequent sessions.

The modules continued in this vein until the family portion of treatment had completed. By this time, Kevin had developed a good rapport with his clinician, and he continued treatment despite his persistent reservations about accepting his illness. The family environment improved, and though Kevin was only sporadically compliant with his medication, the reduced stress at home and improved coping skills drove him less often to use marijuana for "self-medication," which decreased his manic episodes.

Kevin’s family periodically rejoined him in treatment sessions at predefined intervals, to check in and assess his and their progress. They were comfortable speaking with Kevin’s doctor and would call when they noticed any of the warning signs that they had collaboratively determined as markers of upcoming mania. In this way, they were all effective at keeping Kevin’s moods stable and keeping him out of the hospital.

The psychiatrist in routine practice might neither follow a manualized algorithm for family treatment nor have the time or resources at her disposal to provide a full "curriculum." Still, she can have the same success in engaging a family in understanding their loved one’s illness and contributing to the family member’s stability.

Objectives for family-focused treatment

The following objectives are adapted from "Bipolar Disorder: A Family-Focused Treatment Approach," 2nd ed. (New York: The Guilford Press, 2010):

• Encourage the patient and the family to admit that there is a vulnerability to future episodes by educating them about the natural course, progression, and chronic nature of bipolar disorder.

• Enable the patient and the family to recognize that medications are important for controlling symptoms. Provide concrete evidence for the importance and efficacy of medications and the risks of discontinuation. Explore reasons for resisting medications, including fears about becoming dependent.

• Help the patient and the family see the differences between the patient’s personality and his/her illness. Make a list of the patient’s positive attributes and a separate list of warning signs of mania. Frequently reinforce the distinction between the two.

• Assist the patient and the family in dealing with stressors that might cause a recurrence and help them rebuild family relationship ruptures after an episode. Suggest methods for positive, constructive communication such as active listening (nodding, making eye contact, paraphrasing, asking relevant questions) and expressing positive feelings toward a family member related to a specific example of a behavior.

Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013). Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City.