User login

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

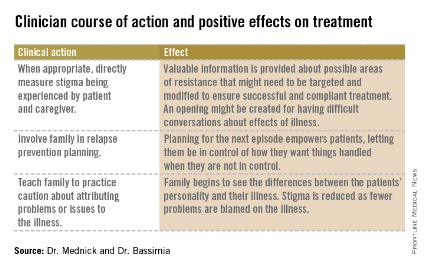

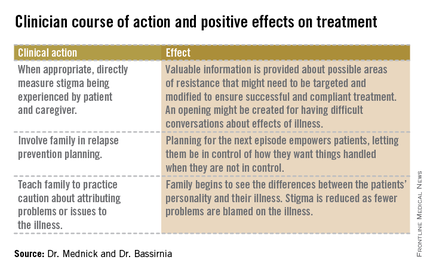

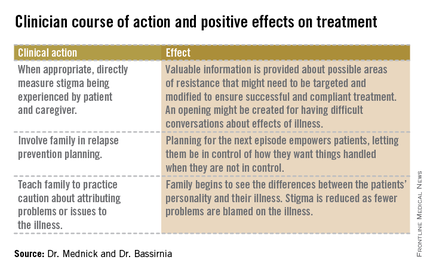

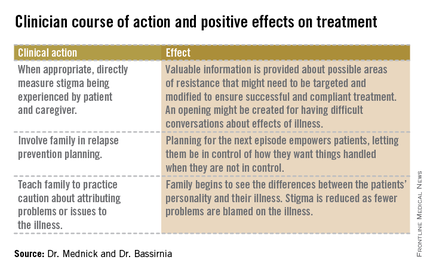

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.

Naomi is a 61-year-old woman who has lived with bipolar disorder and its stigma for 30 years. After a major manic episode and hospitalization, she entered into family treatment at the urging of her three daughters. Previously, her husband had been the primary force in guiding her psychiatric care, and she had been in treatment with a psychiatrist who is his professional colleague.

The patient’s first depressive episode began in the postpartum period, but she did not seek help at that time because she thought that her feelings were normal for a new mother. She did not receive any psychiatric attention until she cycled into mania and called the police for fear her child was being poisoned by neighbors. Her most recent manic episode occurred after she stopped her medications because of concerns about side effects. She was too embarrassed to tell her husband or doctor. She routinely fails to tell her other medical doctors that she is on mood stabilizers, because she does not want them to know she has bipolar disorder.

As Naomi recovers from the most recent manic episode and settles into family treatment, she is struggling with the consequences of her actions to her family. In family therapy in the past, her husband has revealed his belief that he has been protecting the family from Naomi’s mania and protecting Naomi from "embarrassing herself." This is difficult for Naomi to hear as she has always prided herself on being a good mother and protecting her daughters. Naomi’s situation illustrates the difficulty of coping with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, the consequences of the illness on the family, and the importance of addressing stigma.

How stigma gets in the way

As discussed previously by Dr. Alison M. Heru ("Mental illness stigma is a family affair," Clinical Psychiatry News, April 2014, p. 8), stigma, when internalized or self-directed, can lead to psychological distress, decreased self-esteem and life satisfaction, and increased depression and suicidality (Compr. Psychiatry 2010;51:603-6). Close family members of those with mental disorders are affected by stigma, commonly referred to as "stigma by association" or "courtesy stigma."

Up to 92% of caregivers of people with psychiatric disorders have reported internalized stigma (J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012;19:665-71). These family members become distant and avoidant, resulting in a reduced quality of life and an impaired ability to provide critical support for their loved ones. Caregiver anxiety is inversely related to patient anxiety, stigma, and poor alliance (J. Nerv. Ment. Disease 2011;199:18-24).

As a result of these factors, while people with psychiatric disorders have to cope with their own mental illness as well as the public and self-stigma that alienate them from society, they also are at risk of losing their family connections.

In order to confront stigma, the Family Center for Bipolar Disorder in New York City, for example, uses a Family Inclusive Treatment (FIT) model. The FIT model includes an engagement period at the initiation of treatment that is focused on psychoeducation and relapse prevention planning. FIT is unique in that every patient is required to sign a release of information giving permission for full, open communication at all times between the patient’s clinician and a treatment partner of their choice. After the initial engagement period, there are quarterly family visits to supplement regular individual treatment sessions. FIT treatment promotes open communication about symptoms and medications. FIT strives to minimize patient isolation from families; they can talk openly with one another and their clinician.

After seeing many families enter treatment, FIT staff noticed the prominence of stigma.

We have begun to ask about stigma directly. Do people with more stigma do worse in treatment? Do they adhere more poorly to treatment? Do their families tend to become less involved over time? To begin, Dr. Mednick and staff examined demographic data looking for factors that might predispose a person to experience increased stigma.

In terms of diagnosis, people with more internalizing disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders tend to experience more stigma. Distress is experienced internally. As Dr. Bassirnia and her colleagues wrote in a poster presented at the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting, people with externalizing disorders, such as substance abuse and antisocial disorders, are more likely to express their distress outwardly and are less likely to suffer from stigma ("The relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their caregivers," 2014).

Meanwhile, two systematic review studies have reported moderate to high levels of internalized stigma in people with bipolar disorder. In these studies, a higher level of internalized stigma had a negative correlation with self-esteem, social adjustment, and perceived social support, and positive correlation with severity of symptoms, functional impairment, and rehospitalization. In spite of having more severe symptoms; people with higher levels of self-stigma are less likely to seek professional help and adhere to their treatment. Stigma by association and its negative consequences in caregivers of people with mental disorders also have been reported (J. Affect. Disord. 2013;150:181-91).

A useful and easy to administer scale that helps to identify stigma is the "Perceived Criticism Scale" (J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1989;98:225-35). By asking four questions, the clinician can get a good sense of family dynamics and can monitor the progress and change over time. The questions rate perception on a scale of 1-10, where "X" is the other person involved in treatment, either patient or caregiver. Here are the questions:

1. How critical do you think you are of X?

2. How critical do you think X is of you?

3. When X criticizes you, how upset do you get?

4. When you criticize X, how upset does he/she get?

For families with high scores, follow-up is needed. The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale (Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:31-49) can be used. The ISMI scale makes statements about stigma for which participants rate their agreement on a Likert scale, such as:

• I don’t talk about myself much because I don’t want to burden others with my mental illness.

• Being around people who don’t have a mental illness makes me feel out of place or inadequate.

• People can tell that I have a mental illness by the way I look.

• Mentally ill people tend to be violent.

• I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness.

The ISMI scale contains 29 short, simple statements like the ones above and can be completed in less than 10 minutes. The statements are designed to avoid hypothetical situations, stay focused in the present, and address the participant’s own identity and experience.

Using the tools in practice

Naomi entered family treatment with her husband and daughters. Using the ISMI to measure the stigma of mental illness that each family member was experiencing, Naomi was shocked to see that her daughters felt far less stigma about having a mother with mental illness than she had assumed. In turn, her daughters were shocked at how much stigma Naomi was experiencing. Naomi’s husband scored between them. This data paved the way for an open family conversation about how Naomi’s illness had affected their lives, and especially how Naomi’s husband and his perceptions of her illness had affected her treatment course.

Caregivers play a very important role in bipolar disorder. After all, the illness can lead to difficulty functioning and can threaten the family’s stability. Sometimes caregivers can serve as a source of strength and a beacon of stability in the occasional storm. It is hard for the family between the storms, when the same flashing beacon can be a constant reminder to the patient of their illness. Often, well intentioned concerns become constant checking up, making the patient feel stigmatized and expected to fail.

"Good" caregivers will be aware of the stigma and the impact it has on their loved one and on themselves, without becoming a source of stigma.

Dr. Mednick is an attending psychiatrist at the Family Center for Bipolar at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York City. Dr. Bassirnia is a second-year psychiatry resident at Mount Sinai Beth Israel. Scan the QR code to read more Families in Psychiatry columns at clinicalpsychiatrynews.com.