User login

Defining Potential Overutilization of Physical Therapy Consults on Hospital Medicine Services

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

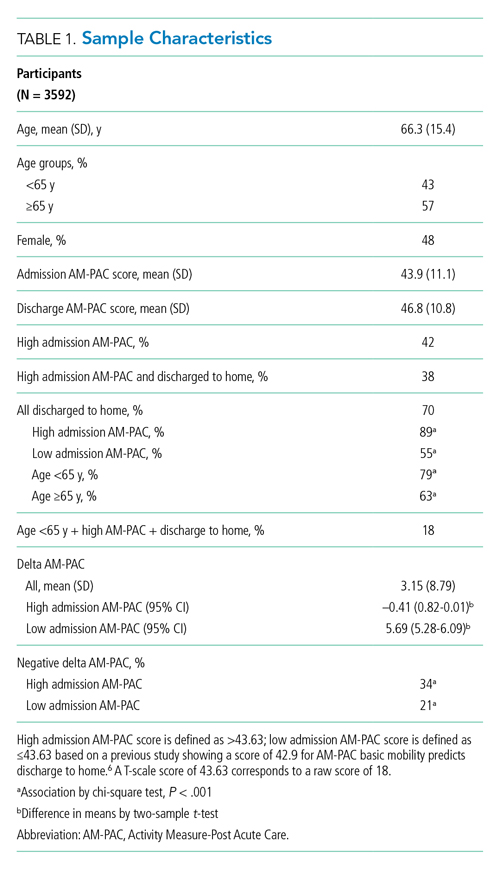

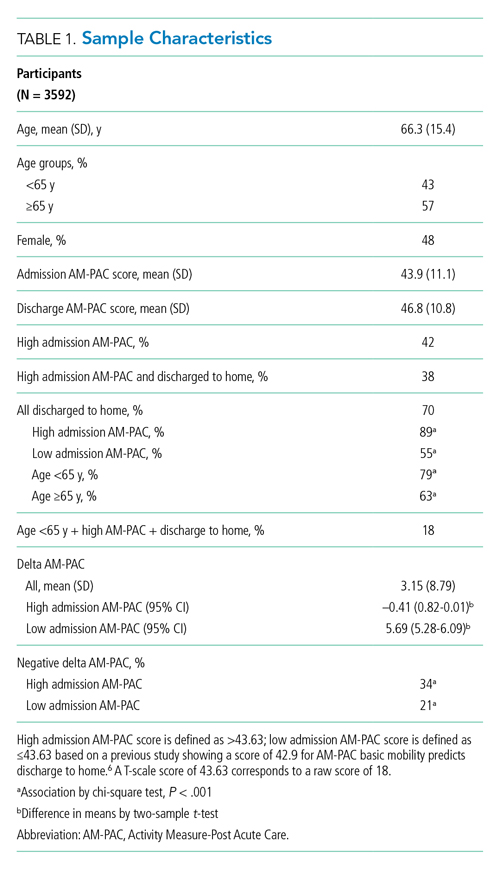

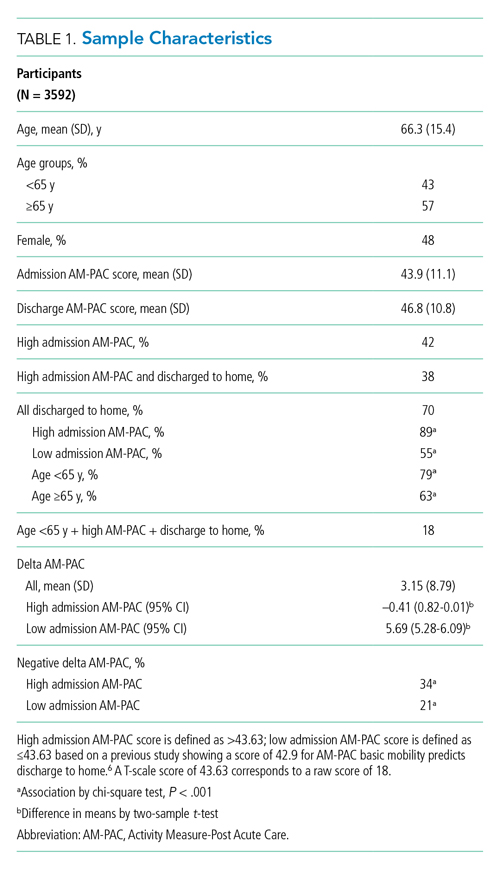

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

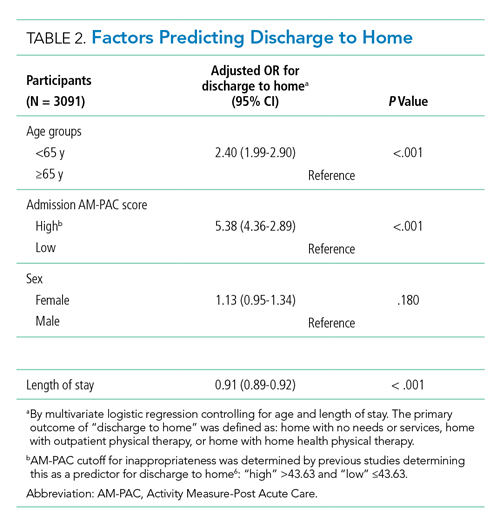

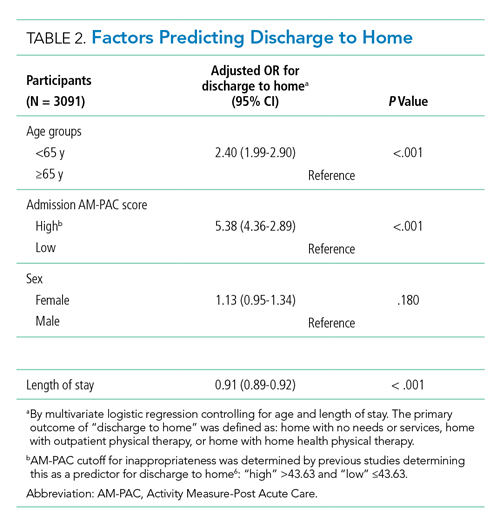

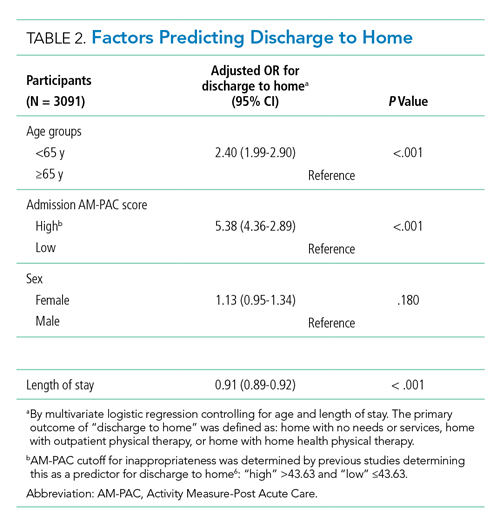

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Implementing Physical Distancing in the Hospital: A Key Strategy to Prevent Nosocomial Transmission of COVID-19

Hospitalists serve as frontline healthcare professionals caring for the increasing number of COVID-19 patients in the United States. The safety of hospitalists and other frontline healthcare workers is paramount to preventing high nosocomial transmission as has been reported in several other countries. Much effort to date has rightly focused on ensuring healthcare workers have appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) given the known increased risk of nosocomial infection to healthcare workers. However, another important strategy to prevent nosocomial transmission is to implement “social distancing,” or avoiding close contact with others. While this approach has received considerable press with regards to implementation in communities, social, or physical, distancing in the hospital is also a critical way to prevent nosocomial transmission and ensure the health and welfare of our workforce to meet the challenge. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines close contact as less than 6 feet away for over 10 minutes.1 Given the myriad clinical interactions that occur within teams in the hospital, such distancing can prove challenging.

At the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois, our hospitalist group was an early adopter of implementing several strategies to facilitate physical distancing in the context of clinical care to minimize community transmission of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals. We describe how to implement physical distancing effectively in specific hospital settings, including some challenges and strategies to surmount them.

EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCES AND ADMINISTRATIVE MEETINGS

Educational conferences and administrative meetings need to be transitioned to virtual meetings. While it may be easy to broadcast a conference in lieu of meeting in a conference room, it is critical that hospital clinicians do not “huddle close together” in front of a computer, which would defeat the purpose of physical distancing. While “flipping the classroom” in preclinical and higher education is common, this method can be effective to deliver standard education followed by a virtual question and answer session or chat room.2

Educational discussions can also occur asynchronously through learning management systems, such as Canvas, or even closed social media channels, such as Slack, that enable discussions. These tools require training to work, so it is important to invest in education on the chosen platform to ensure that it functions smoothly. It is equally important that administrators become familiar with these tools while working remotely and can facilitate administrative meetings without difficulty. We created a one-page tip sheet to help ease the transition for department administrators. The tip sheet highlighted how to start a virtual meeting and meeting etiquette (eg, mute upon entry into the meeting, mute when not talking, announce yourself when talking) as well as ensuring that dial-ins could easily access the meeting by including one-touch options, when available, on calendar invites in addition to the weblink. A daily email update can be an important adjunct to administrative meetings to ensure critical updates are reaching all clinicians in a group and also preserves meeting time for clarifying questions.

CLINICAL WORKROOMS

Perhaps the biggest challenge is how many clinical workrooms in hospitals today are crowded with computers next to each other. Ventilation can also be poor, making conditions riskier. This makes implemention of social distancing extremely challenging, but also critical, given how much time hospital-based clinicians spend on computers and in their workrooms. The first step to achieving social distancing in the workroom is to take an inventory of how many people work there and get a log of the number of computers. Consider whether existing computers can be rearranged with a goal of keeping people 6 feet apart. For particularly cramped workrooms, this may require assigning computer spaces to physicians across a floor or several floors, using computers out on a unit, or using mobile computers to limit the number of people in the workroom at one time. We suggest working with physical plant leaders and Information Technology to reallocate mobile workstations, laptops, or desktops to conference rooms, patient visiting areas, and offices that are not being used. Because coronavirus can survive on surfaces for several hours, it is also important to stock work rooms with disinfectants to clean surfaces such as keyboards and desktops frequently. One other important thing to consider is whether computers can be assigned to specific teams or people to limit the use of a computer by multiple people.

ROUNDING, SIGN-OUT, AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY ROUNDS

Rounding

Perhaps one of the most fundamental hardships with physical distancing is how to conduct routine clinical care such as rounds, sign-out, or multidisciplinary rounds. Rounds on teaching services are particularly challenging given the number of people. At many teaching institutions, medical students are no longer on clinical rotations, which immediately reduces the number of people on teaching teams. The other thing to consider is how rounds are conducted. As opposed to a large team walking together, assign one person from the team as the liaison for the patient, which also has the added benefit of conserving precious PPE. Virtual rounding enables clinicians, including residents and attendings, to work together and decide the plan for the day without first crowding into a patient room. This is perhaps the most important cultural hurdle that one may face.

Another administrative hurdle and common concern is how to bill for such interactions. While federal guidance evolves, our institution created smartphrases for this type of virtual rounding whereby attendings attest to resident notes even if they did not physically see the patient. Additional information may be obtained from patients by calling them on their patient-room phones or by using telemedicine as some hospitals are implementing.3 For large “mega” teams, split the team into smaller groups to facilitate continuity and easier conversations.

Sign-out

When feasible, it is important to transition to phone sign-out supplemented with viewing an updated shared sign-out, ideally electronically, for shift change. When using phone sign-out, it is ideal to implement a verbal read-back to ensure understanding and to keep your sign-out updated. Because using the telephone is not the most effective communication channel for sign-out, it is key to be vigilant with other sign-out best practices, such as using a standard template like IPASS4 or another framework, prioritizing sick patients, and ensuring a focus on to-do and if/then items that are critical for the receiver to ensure understanding.5

Multidisciplinary Rounds

As multidisciplinary rounds typically occur either at the bedside or in a conference room, it is key to ensure that these occur virtually whenever possible. One option is to use conference calls or video chat (eg, Zoom) for multidisciplinary rounds whenever possible. Calendar invites or paging reminders can be used to prompt teams when to call in to discuss patients. Because multiple people are entering a virtual room at once, it is important to establish an order or have a leader orchestrate who is next. In addition, given the importance of multiple people contributing to the discussion, it is also equally important for those speaking always to announce who they are and their role (eg, social worker, case manager, physical therapist) since it may not be possible to recognize people’s voices alone. This is where visual recognition can be helpful through use of institutional video conferencing that enables hearing and seeing someone. Further, it is important to ensure that the platform being used is HIPAA compliant.

CALL ROOMS

Call rooms in hospitals can be particularly challenging if they are shared. Finding additional call rooms may require use of cots or reallocation of patient rooms. It is also possible for hospitalists to consider air mattresses in their offices or other private spaces to avoid sharing call rooms. Consider assigning the same call room to the same few people over the course of a rotation or period to avoid many people sharing one room. If a hospital is converting units to group patients under investigation or those who are COVID-19 positive, reallocating call rooms may be necessary to accommodate new teams. Lastly, it is important to communicate proactively with environmental services staff to make sure all call rooms are equipped with cleaning supplies and hand sanitizer and are cleaned daily to avoid nosocomial transmission.

CONCLUSION

/section>Containing nosocomial spread of coronavirus is particularly challenging for hospitals because of how contagious the virus is, the extreme shortage of PPE, and lack of mass testing to identify those who are sick. Therefore, physical distancing in the hospital is critical to ensure the health and well-being of the health professional workforce during the pandemic.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed April 2, 2020.

2. Stephenson CR, Wang AT, Szostek JH, et al. Flipping the continuing medical education classroom: validating a measure of attendees’ perceptions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000113.

3. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, K Mathews BK, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):xxx-xxxx. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556.

5. Gaffney S, Farnan JM, Hirsch K, McGinty M, Arora VM. The modified, multi-patient observed simulated handoff experience (M-OSHE): assessment and feedback for entering residents on handoff performance. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):438-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3591-8.

Hospitalists serve as frontline healthcare professionals caring for the increasing number of COVID-19 patients in the United States. The safety of hospitalists and other frontline healthcare workers is paramount to preventing high nosocomial transmission as has been reported in several other countries. Much effort to date has rightly focused on ensuring healthcare workers have appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) given the known increased risk of nosocomial infection to healthcare workers. However, another important strategy to prevent nosocomial transmission is to implement “social distancing,” or avoiding close contact with others. While this approach has received considerable press with regards to implementation in communities, social, or physical, distancing in the hospital is also a critical way to prevent nosocomial transmission and ensure the health and welfare of our workforce to meet the challenge. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines close contact as less than 6 feet away for over 10 minutes.1 Given the myriad clinical interactions that occur within teams in the hospital, such distancing can prove challenging.

At the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois, our hospitalist group was an early adopter of implementing several strategies to facilitate physical distancing in the context of clinical care to minimize community transmission of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals. We describe how to implement physical distancing effectively in specific hospital settings, including some challenges and strategies to surmount them.

EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCES AND ADMINISTRATIVE MEETINGS

Educational conferences and administrative meetings need to be transitioned to virtual meetings. While it may be easy to broadcast a conference in lieu of meeting in a conference room, it is critical that hospital clinicians do not “huddle close together” in front of a computer, which would defeat the purpose of physical distancing. While “flipping the classroom” in preclinical and higher education is common, this method can be effective to deliver standard education followed by a virtual question and answer session or chat room.2

Educational discussions can also occur asynchronously through learning management systems, such as Canvas, or even closed social media channels, such as Slack, that enable discussions. These tools require training to work, so it is important to invest in education on the chosen platform to ensure that it functions smoothly. It is equally important that administrators become familiar with these tools while working remotely and can facilitate administrative meetings without difficulty. We created a one-page tip sheet to help ease the transition for department administrators. The tip sheet highlighted how to start a virtual meeting and meeting etiquette (eg, mute upon entry into the meeting, mute when not talking, announce yourself when talking) as well as ensuring that dial-ins could easily access the meeting by including one-touch options, when available, on calendar invites in addition to the weblink. A daily email update can be an important adjunct to administrative meetings to ensure critical updates are reaching all clinicians in a group and also preserves meeting time for clarifying questions.

CLINICAL WORKROOMS

Perhaps the biggest challenge is how many clinical workrooms in hospitals today are crowded with computers next to each other. Ventilation can also be poor, making conditions riskier. This makes implemention of social distancing extremely challenging, but also critical, given how much time hospital-based clinicians spend on computers and in their workrooms. The first step to achieving social distancing in the workroom is to take an inventory of how many people work there and get a log of the number of computers. Consider whether existing computers can be rearranged with a goal of keeping people 6 feet apart. For particularly cramped workrooms, this may require assigning computer spaces to physicians across a floor or several floors, using computers out on a unit, or using mobile computers to limit the number of people in the workroom at one time. We suggest working with physical plant leaders and Information Technology to reallocate mobile workstations, laptops, or desktops to conference rooms, patient visiting areas, and offices that are not being used. Because coronavirus can survive on surfaces for several hours, it is also important to stock work rooms with disinfectants to clean surfaces such as keyboards and desktops frequently. One other important thing to consider is whether computers can be assigned to specific teams or people to limit the use of a computer by multiple people.

ROUNDING, SIGN-OUT, AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY ROUNDS

Rounding

Perhaps one of the most fundamental hardships with physical distancing is how to conduct routine clinical care such as rounds, sign-out, or multidisciplinary rounds. Rounds on teaching services are particularly challenging given the number of people. At many teaching institutions, medical students are no longer on clinical rotations, which immediately reduces the number of people on teaching teams. The other thing to consider is how rounds are conducted. As opposed to a large team walking together, assign one person from the team as the liaison for the patient, which also has the added benefit of conserving precious PPE. Virtual rounding enables clinicians, including residents and attendings, to work together and decide the plan for the day without first crowding into a patient room. This is perhaps the most important cultural hurdle that one may face.

Another administrative hurdle and common concern is how to bill for such interactions. While federal guidance evolves, our institution created smartphrases for this type of virtual rounding whereby attendings attest to resident notes even if they did not physically see the patient. Additional information may be obtained from patients by calling them on their patient-room phones or by using telemedicine as some hospitals are implementing.3 For large “mega” teams, split the team into smaller groups to facilitate continuity and easier conversations.

Sign-out

When feasible, it is important to transition to phone sign-out supplemented with viewing an updated shared sign-out, ideally electronically, for shift change. When using phone sign-out, it is ideal to implement a verbal read-back to ensure understanding and to keep your sign-out updated. Because using the telephone is not the most effective communication channel for sign-out, it is key to be vigilant with other sign-out best practices, such as using a standard template like IPASS4 or another framework, prioritizing sick patients, and ensuring a focus on to-do and if/then items that are critical for the receiver to ensure understanding.5

Multidisciplinary Rounds

As multidisciplinary rounds typically occur either at the bedside or in a conference room, it is key to ensure that these occur virtually whenever possible. One option is to use conference calls or video chat (eg, Zoom) for multidisciplinary rounds whenever possible. Calendar invites or paging reminders can be used to prompt teams when to call in to discuss patients. Because multiple people are entering a virtual room at once, it is important to establish an order or have a leader orchestrate who is next. In addition, given the importance of multiple people contributing to the discussion, it is also equally important for those speaking always to announce who they are and their role (eg, social worker, case manager, physical therapist) since it may not be possible to recognize people’s voices alone. This is where visual recognition can be helpful through use of institutional video conferencing that enables hearing and seeing someone. Further, it is important to ensure that the platform being used is HIPAA compliant.

CALL ROOMS

Call rooms in hospitals can be particularly challenging if they are shared. Finding additional call rooms may require use of cots or reallocation of patient rooms. It is also possible for hospitalists to consider air mattresses in their offices or other private spaces to avoid sharing call rooms. Consider assigning the same call room to the same few people over the course of a rotation or period to avoid many people sharing one room. If a hospital is converting units to group patients under investigation or those who are COVID-19 positive, reallocating call rooms may be necessary to accommodate new teams. Lastly, it is important to communicate proactively with environmental services staff to make sure all call rooms are equipped with cleaning supplies and hand sanitizer and are cleaned daily to avoid nosocomial transmission.

CONCLUSION

/section>Containing nosocomial spread of coronavirus is particularly challenging for hospitals because of how contagious the virus is, the extreme shortage of PPE, and lack of mass testing to identify those who are sick. Therefore, physical distancing in the hospital is critical to ensure the health and well-being of the health professional workforce during the pandemic.

Hospitalists serve as frontline healthcare professionals caring for the increasing number of COVID-19 patients in the United States. The safety of hospitalists and other frontline healthcare workers is paramount to preventing high nosocomial transmission as has been reported in several other countries. Much effort to date has rightly focused on ensuring healthcare workers have appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) given the known increased risk of nosocomial infection to healthcare workers. However, another important strategy to prevent nosocomial transmission is to implement “social distancing,” or avoiding close contact with others. While this approach has received considerable press with regards to implementation in communities, social, or physical, distancing in the hospital is also a critical way to prevent nosocomial transmission and ensure the health and welfare of our workforce to meet the challenge. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines close contact as less than 6 feet away for over 10 minutes.1 Given the myriad clinical interactions that occur within teams in the hospital, such distancing can prove challenging.

At the University of Chicago Medicine in Illinois, our hospitalist group was an early adopter of implementing several strategies to facilitate physical distancing in the context of clinical care to minimize community transmission of COVID-19 among healthcare professionals. We describe how to implement physical distancing effectively in specific hospital settings, including some challenges and strategies to surmount them.

EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCES AND ADMINISTRATIVE MEETINGS

Educational conferences and administrative meetings need to be transitioned to virtual meetings. While it may be easy to broadcast a conference in lieu of meeting in a conference room, it is critical that hospital clinicians do not “huddle close together” in front of a computer, which would defeat the purpose of physical distancing. While “flipping the classroom” in preclinical and higher education is common, this method can be effective to deliver standard education followed by a virtual question and answer session or chat room.2

Educational discussions can also occur asynchronously through learning management systems, such as Canvas, or even closed social media channels, such as Slack, that enable discussions. These tools require training to work, so it is important to invest in education on the chosen platform to ensure that it functions smoothly. It is equally important that administrators become familiar with these tools while working remotely and can facilitate administrative meetings without difficulty. We created a one-page tip sheet to help ease the transition for department administrators. The tip sheet highlighted how to start a virtual meeting and meeting etiquette (eg, mute upon entry into the meeting, mute when not talking, announce yourself when talking) as well as ensuring that dial-ins could easily access the meeting by including one-touch options, when available, on calendar invites in addition to the weblink. A daily email update can be an important adjunct to administrative meetings to ensure critical updates are reaching all clinicians in a group and also preserves meeting time for clarifying questions.

CLINICAL WORKROOMS

Perhaps the biggest challenge is how many clinical workrooms in hospitals today are crowded with computers next to each other. Ventilation can also be poor, making conditions riskier. This makes implemention of social distancing extremely challenging, but also critical, given how much time hospital-based clinicians spend on computers and in their workrooms. The first step to achieving social distancing in the workroom is to take an inventory of how many people work there and get a log of the number of computers. Consider whether existing computers can be rearranged with a goal of keeping people 6 feet apart. For particularly cramped workrooms, this may require assigning computer spaces to physicians across a floor or several floors, using computers out on a unit, or using mobile computers to limit the number of people in the workroom at one time. We suggest working with physical plant leaders and Information Technology to reallocate mobile workstations, laptops, or desktops to conference rooms, patient visiting areas, and offices that are not being used. Because coronavirus can survive on surfaces for several hours, it is also important to stock work rooms with disinfectants to clean surfaces such as keyboards and desktops frequently. One other important thing to consider is whether computers can be assigned to specific teams or people to limit the use of a computer by multiple people.

ROUNDING, SIGN-OUT, AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY ROUNDS

Rounding

Perhaps one of the most fundamental hardships with physical distancing is how to conduct routine clinical care such as rounds, sign-out, or multidisciplinary rounds. Rounds on teaching services are particularly challenging given the number of people. At many teaching institutions, medical students are no longer on clinical rotations, which immediately reduces the number of people on teaching teams. The other thing to consider is how rounds are conducted. As opposed to a large team walking together, assign one person from the team as the liaison for the patient, which also has the added benefit of conserving precious PPE. Virtual rounding enables clinicians, including residents and attendings, to work together and decide the plan for the day without first crowding into a patient room. This is perhaps the most important cultural hurdle that one may face.

Another administrative hurdle and common concern is how to bill for such interactions. While federal guidance evolves, our institution created smartphrases for this type of virtual rounding whereby attendings attest to resident notes even if they did not physically see the patient. Additional information may be obtained from patients by calling them on their patient-room phones or by using telemedicine as some hospitals are implementing.3 For large “mega” teams, split the team into smaller groups to facilitate continuity and easier conversations.

Sign-out

When feasible, it is important to transition to phone sign-out supplemented with viewing an updated shared sign-out, ideally electronically, for shift change. When using phone sign-out, it is ideal to implement a verbal read-back to ensure understanding and to keep your sign-out updated. Because using the telephone is not the most effective communication channel for sign-out, it is key to be vigilant with other sign-out best practices, such as using a standard template like IPASS4 or another framework, prioritizing sick patients, and ensuring a focus on to-do and if/then items that are critical for the receiver to ensure understanding.5

Multidisciplinary Rounds

As multidisciplinary rounds typically occur either at the bedside or in a conference room, it is key to ensure that these occur virtually whenever possible. One option is to use conference calls or video chat (eg, Zoom) for multidisciplinary rounds whenever possible. Calendar invites or paging reminders can be used to prompt teams when to call in to discuss patients. Because multiple people are entering a virtual room at once, it is important to establish an order or have a leader orchestrate who is next. In addition, given the importance of multiple people contributing to the discussion, it is also equally important for those speaking always to announce who they are and their role (eg, social worker, case manager, physical therapist) since it may not be possible to recognize people’s voices alone. This is where visual recognition can be helpful through use of institutional video conferencing that enables hearing and seeing someone. Further, it is important to ensure that the platform being used is HIPAA compliant.

CALL ROOMS

Call rooms in hospitals can be particularly challenging if they are shared. Finding additional call rooms may require use of cots or reallocation of patient rooms. It is also possible for hospitalists to consider air mattresses in their offices or other private spaces to avoid sharing call rooms. Consider assigning the same call room to the same few people over the course of a rotation or period to avoid many people sharing one room. If a hospital is converting units to group patients under investigation or those who are COVID-19 positive, reallocating call rooms may be necessary to accommodate new teams. Lastly, it is important to communicate proactively with environmental services staff to make sure all call rooms are equipped with cleaning supplies and hand sanitizer and are cleaned daily to avoid nosocomial transmission.

CONCLUSION

/section>Containing nosocomial spread of coronavirus is particularly challenging for hospitals because of how contagious the virus is, the extreme shortage of PPE, and lack of mass testing to identify those who are sick. Therefore, physical distancing in the hospital is critical to ensure the health and well-being of the health professional workforce during the pandemic.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed April 2, 2020.

2. Stephenson CR, Wang AT, Szostek JH, et al. Flipping the continuing medical education classroom: validating a measure of attendees’ perceptions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000113.

3. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, K Mathews BK, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):xxx-xxxx. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556.

5. Gaffney S, Farnan JM, Hirsch K, McGinty M, Arora VM. The modified, multi-patient observed simulated handoff experience (M-OSHE): assessment and feedback for entering residents on handoff performance. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):438-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3591-8.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim U.S. Guidance for Risk Assessment and Public Health Management of Healthcare Personnel with Potential Exposure in a Healthcare Setting to Patients with Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-risk-assesment-hcp.html. Accessed April 2, 2020.

2. Stephenson CR, Wang AT, Szostek JH, et al. Flipping the continuing medical education classroom: validating a measure of attendees’ perceptions. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2016;36(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000113.

3. Doshi A, Platt Y, Dressen JR, K Mathews BK, Siy JC. Keep calm and log on: telemedicine for COVID-19 pandemic response. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(4):xxx-xxxx. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3419.

4. Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, et al. Changes in medical errors after implementation of a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1803-1812. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1405556.

5. Gaffney S, Farnan JM, Hirsch K, McGinty M, Arora VM. The modified, multi-patient observed simulated handoff experience (M-OSHE): assessment and feedback for entering residents on handoff performance. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):438-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3591-8.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine