User login

Moving antibiotic stewardship from theory to practice

We both attend on the Infectious Disease consult team in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals, and predictably the conversation on afternoon rounds often revolves around antibiotics. When we have those discussions, our focus is not on a need to “preserve antibiotics” so they might be available to some unknown patient in the future. Rather, we are working with the primary team to provide the very best treatment for the patient entrusted to our care in the bed right in front of us. We believe it is in this context—providing optimal patient care—that the current efforts in the United States to improve antibiotic use should be viewed.

The growing challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant infections and the related threat of Clostridium difficile infection combine to sicken more than 2 million people each year and contribute to the deaths of more than 25,000 patients.1 Improving antibiotic use through antibiotic stewardship is often proposed to hospitalists as an important part of stemming this tide. While this is true, even as infectious disease specialists with strong interests in antimicrobial stewardship we do not find that pitch compelling when we are on clinical service.

What motivates us to optimize antibiotic use for our patients is the evidence that doing so will have direct and immediate benefits to the patients under our care. Improving antibiotic use has been proven to decrease a patient’s risk of acquiring C. difficile infection or an antibiotic-resistant infection not at some ill-defined time in the future, but during their current hospital stay.2,3 Even more important, support from antibiotic stewardship programs has been proven to improve infection cure rates and reduce the risk of treatment failure for hospitalized patients.4 The bottom line of antibiotic stewardship is better patient care. Sometimes that means narrowing or stopping antibiotics to reduce the risks of adverse events. In other cases, like in the treatment of suspected sepsis, it means ensuring patients get broad spectrum antibiotics quickly.

The patient care benefits of improving antibiotic use led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to issue a call in 2014 for all hospitals to have antibiotic stewardship programs, and to the development of The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs to support that effort. As of January 1, 2017, antibiotic stewardship programs that incorporate all the CDC core elements became an accreditation requirement of The Joint Commission, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has proposed making the same requirement of all hospitals that participate in their payment programs.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: PNEUMONIA

The literature on treatment of pneumonia is increasingly demonstrating that shorter use of antibiotics is often better.7 Even though current guidelines recommend 5 to 7 days of antibiotics for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia, average durations of therapy are often longer.8 Previous work published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine focused on improving antimicrobial documentation as well as access to local clinical guidelines and implementing a 72-hour antimicrobial “time out” by hospitalists.9 When these multimodal interventions tailored for hospitalists were in place, utilization of antibiotics improved. Graber et al.5 also found that facility educational programs for prudent antimicrobial use and frequency of de-escalation review were associated with decreased overall antimicrobial use. Providing vague recommendations on antibiotic course, or none at all, at discharge or sign-out can lead to unnecessary antibiotics or an extended course of them. Pneumonia-specific interventions could target duration by outlining antibiotic course in hospitalist progress notes and at hand-off.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: UTI

Misuse of antibiotics in UTI often stems from overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria or unneeded diagnostic testing. Often, the pivotal step in avoiding unnecessary treatment lies in the ordering of the urine culture.10 Graber et al.5 showed that order sets were associated with decreased antimicrobial use. In the case of UTI, hospitalists could work with the stewardship team to design order sets that guide providers to appropriate reasons for ordering a urine culture. Order sets could also help providers recognize important patient-specific risks for certain antibiotics, such as the risk of C. difficile with fluoroquinolones in an elderly patient. Targeting different steps in overutilization of antibiotics would encompass more prescribers and could lead to reducing other unnecessary testing, which is a current focus for many hospitalists.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: SSTI

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) also offer a specific disease state to use order sets and education to improve duration of antibiotics, decrease overuse of broad spectrum antibiotics, and reduce unnecessary diagnostic studies. For example, gram negative and/or anaerobic coverage are rarely indicated in treating SSTIs but are often used. SSTI-specific order sets and guidelines have already been shown to improve both diagnostic work-up and antibiotic treatment.11 As the providers who manage most of these infections in hospitals, hospitalists are ideally positioned to inform the development of SSTI order sets and pathways. The work by Graber et al.5 provides some important insights into how we can effectively implement interventions to improve antibiotic use. These insights have never been more important as more hospitals move toward starting or expanding antibiotic stewardship programs. As leaders in patient safety and quality, and as the most important antibiotic prescribers in hospitals, hospitalists must play a central role in stewardship if we are to make meaningful progress.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

2. Feazel LM, Malhotra A, Perencevich EN, Kaboli P, Diekema DJ, Schweizer ML. Effect of antibiotic stewardship programmes on Clostridium difficile incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1748-1754. PubMed

3. Singh N, Rogers P, Atwood CW, Wagener MM, Yu VL. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):505-511. PubMed

4. Fishman N. Antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Med. 2006;119(6 Suppl 1):S53-S61; discussion S62-S70. PubMed

5. Graber CJ, Jones MM, Chou AF, et al. Association of inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures with antimicrobial stewardship activities and facility characteristics of Veterans Affairs medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:301-309. PubMed

6. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. PubMed

7. Viasus D, Vecino-Moreno M, De La Hoz JM, Carratala J. Antibiotic stewardship in community-acquired pneumonia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016:1-2019. PubMed

8. Avdic E, Cushinotto LA, Hughes AH, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on shortening the duration of therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1581-1587. PubMed

9. Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):576-580. PubMed

10. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach for Urinary Catheter-Associated Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120-1127. PubMed

11. Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1072-1079. PubMed

We both attend on the Infectious Disease consult team in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals, and predictably the conversation on afternoon rounds often revolves around antibiotics. When we have those discussions, our focus is not on a need to “preserve antibiotics” so they might be available to some unknown patient in the future. Rather, we are working with the primary team to provide the very best treatment for the patient entrusted to our care in the bed right in front of us. We believe it is in this context—providing optimal patient care—that the current efforts in the United States to improve antibiotic use should be viewed.

The growing challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant infections and the related threat of Clostridium difficile infection combine to sicken more than 2 million people each year and contribute to the deaths of more than 25,000 patients.1 Improving antibiotic use through antibiotic stewardship is often proposed to hospitalists as an important part of stemming this tide. While this is true, even as infectious disease specialists with strong interests in antimicrobial stewardship we do not find that pitch compelling when we are on clinical service.

What motivates us to optimize antibiotic use for our patients is the evidence that doing so will have direct and immediate benefits to the patients under our care. Improving antibiotic use has been proven to decrease a patient’s risk of acquiring C. difficile infection or an antibiotic-resistant infection not at some ill-defined time in the future, but during their current hospital stay.2,3 Even more important, support from antibiotic stewardship programs has been proven to improve infection cure rates and reduce the risk of treatment failure for hospitalized patients.4 The bottom line of antibiotic stewardship is better patient care. Sometimes that means narrowing or stopping antibiotics to reduce the risks of adverse events. In other cases, like in the treatment of suspected sepsis, it means ensuring patients get broad spectrum antibiotics quickly.

The patient care benefits of improving antibiotic use led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to issue a call in 2014 for all hospitals to have antibiotic stewardship programs, and to the development of The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs to support that effort. As of January 1, 2017, antibiotic stewardship programs that incorporate all the CDC core elements became an accreditation requirement of The Joint Commission, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has proposed making the same requirement of all hospitals that participate in their payment programs.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: PNEUMONIA

The literature on treatment of pneumonia is increasingly demonstrating that shorter use of antibiotics is often better.7 Even though current guidelines recommend 5 to 7 days of antibiotics for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia, average durations of therapy are often longer.8 Previous work published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine focused on improving antimicrobial documentation as well as access to local clinical guidelines and implementing a 72-hour antimicrobial “time out” by hospitalists.9 When these multimodal interventions tailored for hospitalists were in place, utilization of antibiotics improved. Graber et al.5 also found that facility educational programs for prudent antimicrobial use and frequency of de-escalation review were associated with decreased overall antimicrobial use. Providing vague recommendations on antibiotic course, or none at all, at discharge or sign-out can lead to unnecessary antibiotics or an extended course of them. Pneumonia-specific interventions could target duration by outlining antibiotic course in hospitalist progress notes and at hand-off.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: UTI

Misuse of antibiotics in UTI often stems from overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria or unneeded diagnostic testing. Often, the pivotal step in avoiding unnecessary treatment lies in the ordering of the urine culture.10 Graber et al.5 showed that order sets were associated with decreased antimicrobial use. In the case of UTI, hospitalists could work with the stewardship team to design order sets that guide providers to appropriate reasons for ordering a urine culture. Order sets could also help providers recognize important patient-specific risks for certain antibiotics, such as the risk of C. difficile with fluoroquinolones in an elderly patient. Targeting different steps in overutilization of antibiotics would encompass more prescribers and could lead to reducing other unnecessary testing, which is a current focus for many hospitalists.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: SSTI

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) also offer a specific disease state to use order sets and education to improve duration of antibiotics, decrease overuse of broad spectrum antibiotics, and reduce unnecessary diagnostic studies. For example, gram negative and/or anaerobic coverage are rarely indicated in treating SSTIs but are often used. SSTI-specific order sets and guidelines have already been shown to improve both diagnostic work-up and antibiotic treatment.11 As the providers who manage most of these infections in hospitals, hospitalists are ideally positioned to inform the development of SSTI order sets and pathways. The work by Graber et al.5 provides some important insights into how we can effectively implement interventions to improve antibiotic use. These insights have never been more important as more hospitals move toward starting or expanding antibiotic stewardship programs. As leaders in patient safety and quality, and as the most important antibiotic prescribers in hospitals, hospitalists must play a central role in stewardship if we are to make meaningful progress.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

We both attend on the Infectious Disease consult team in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals, and predictably the conversation on afternoon rounds often revolves around antibiotics. When we have those discussions, our focus is not on a need to “preserve antibiotics” so they might be available to some unknown patient in the future. Rather, we are working with the primary team to provide the very best treatment for the patient entrusted to our care in the bed right in front of us. We believe it is in this context—providing optimal patient care—that the current efforts in the United States to improve antibiotic use should be viewed.

The growing challenges posed by antibiotic-resistant infections and the related threat of Clostridium difficile infection combine to sicken more than 2 million people each year and contribute to the deaths of more than 25,000 patients.1 Improving antibiotic use through antibiotic stewardship is often proposed to hospitalists as an important part of stemming this tide. While this is true, even as infectious disease specialists with strong interests in antimicrobial stewardship we do not find that pitch compelling when we are on clinical service.

What motivates us to optimize antibiotic use for our patients is the evidence that doing so will have direct and immediate benefits to the patients under our care. Improving antibiotic use has been proven to decrease a patient’s risk of acquiring C. difficile infection or an antibiotic-resistant infection not at some ill-defined time in the future, but during their current hospital stay.2,3 Even more important, support from antibiotic stewardship programs has been proven to improve infection cure rates and reduce the risk of treatment failure for hospitalized patients.4 The bottom line of antibiotic stewardship is better patient care. Sometimes that means narrowing or stopping antibiotics to reduce the risks of adverse events. In other cases, like in the treatment of suspected sepsis, it means ensuring patients get broad spectrum antibiotics quickly.

The patient care benefits of improving antibiotic use led the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to issue a call in 2014 for all hospitals to have antibiotic stewardship programs, and to the development of The Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs to support that effort. As of January 1, 2017, antibiotic stewardship programs that incorporate all the CDC core elements became an accreditation requirement of The Joint Commission, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has proposed making the same requirement of all hospitals that participate in their payment programs.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: PNEUMONIA

The literature on treatment of pneumonia is increasingly demonstrating that shorter use of antibiotics is often better.7 Even though current guidelines recommend 5 to 7 days of antibiotics for uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia, average durations of therapy are often longer.8 Previous work published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine focused on improving antimicrobial documentation as well as access to local clinical guidelines and implementing a 72-hour antimicrobial “time out” by hospitalists.9 When these multimodal interventions tailored for hospitalists were in place, utilization of antibiotics improved. Graber et al.5 also found that facility educational programs for prudent antimicrobial use and frequency of de-escalation review were associated with decreased overall antimicrobial use. Providing vague recommendations on antibiotic course, or none at all, at discharge or sign-out can lead to unnecessary antibiotics or an extended course of them. Pneumonia-specific interventions could target duration by outlining antibiotic course in hospitalist progress notes and at hand-off.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: UTI

Misuse of antibiotics in UTI often stems from overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria or unneeded diagnostic testing. Often, the pivotal step in avoiding unnecessary treatment lies in the ordering of the urine culture.10 Graber et al.5 showed that order sets were associated with decreased antimicrobial use. In the case of UTI, hospitalists could work with the stewardship team to design order sets that guide providers to appropriate reasons for ordering a urine culture. Order sets could also help providers recognize important patient-specific risks for certain antibiotics, such as the risk of C. difficile with fluoroquinolones in an elderly patient. Targeting different steps in overutilization of antibiotics would encompass more prescribers and could lead to reducing other unnecessary testing, which is a current focus for many hospitalists.

STEWARDSHIP IN PRACTICE: SSTI

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) also offer a specific disease state to use order sets and education to improve duration of antibiotics, decrease overuse of broad spectrum antibiotics, and reduce unnecessary diagnostic studies. For example, gram negative and/or anaerobic coverage are rarely indicated in treating SSTIs but are often used. SSTI-specific order sets and guidelines have already been shown to improve both diagnostic work-up and antibiotic treatment.11 As the providers who manage most of these infections in hospitals, hospitalists are ideally positioned to inform the development of SSTI order sets and pathways. The work by Graber et al.5 provides some important insights into how we can effectively implement interventions to improve antibiotic use. These insights have never been more important as more hospitals move toward starting or expanding antibiotic stewardship programs. As leaders in patient safety and quality, and as the most important antibiotic prescribers in hospitals, hospitalists must play a central role in stewardship if we are to make meaningful progress.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

2. Feazel LM, Malhotra A, Perencevich EN, Kaboli P, Diekema DJ, Schweizer ML. Effect of antibiotic stewardship programmes on Clostridium difficile incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1748-1754. PubMed

3. Singh N, Rogers P, Atwood CW, Wagener MM, Yu VL. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):505-511. PubMed

4. Fishman N. Antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Med. 2006;119(6 Suppl 1):S53-S61; discussion S62-S70. PubMed

5. Graber CJ, Jones MM, Chou AF, et al. Association of inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures with antimicrobial stewardship activities and facility characteristics of Veterans Affairs medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:301-309. PubMed

6. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. PubMed

7. Viasus D, Vecino-Moreno M, De La Hoz JM, Carratala J. Antibiotic stewardship in community-acquired pneumonia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016:1-2019. PubMed

8. Avdic E, Cushinotto LA, Hughes AH, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on shortening the duration of therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1581-1587. PubMed

9. Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):576-580. PubMed

10. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach for Urinary Catheter-Associated Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120-1127. PubMed

11. Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1072-1079. PubMed

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

2. Feazel LM, Malhotra A, Perencevich EN, Kaboli P, Diekema DJ, Schweizer ML. Effect of antibiotic stewardship programmes on Clostridium difficile incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1748-1754. PubMed

3. Singh N, Rogers P, Atwood CW, Wagener MM, Yu VL. Short-course empiric antibiotic therapy for patients with pulmonary infiltrates in the intensive care unit. A proposed solution for indiscriminate antibiotic prescription. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):505-511. PubMed

4. Fishman N. Antimicrobial stewardship. Am J Med. 2006;119(6 Suppl 1):S53-S61; discussion S62-S70. PubMed

5. Graber CJ, Jones MM, Chou AF, et al. Association of inpatient antimicrobial utilization measures with antimicrobial stewardship activities and facility characteristics of Veterans Affairs medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:301-309. PubMed

6. Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial use in US acute care hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438-1446. PubMed

7. Viasus D, Vecino-Moreno M, De La Hoz JM, Carratala J. Antibiotic stewardship in community-acquired pneumonia. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016:1-2019. PubMed

8. Avdic E, Cushinotto LA, Hughes AH, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on shortening the duration of therapy for community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(11):1581-1587. PubMed

9. Mack MR, Rohde JM, Jacobsen D, et al. Engaging hospitalists in antimicrobial stewardship: Lessons from a multihospital collaborative. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):576-580. PubMed

10. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Approach for Urinary Catheter-Associated Asymptomatic Bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120-1127. PubMed

11. Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Sabel AL, et al. Decreased antibiotic utilization after implementation of a guideline for inpatient cellulitis and cutaneous abscess. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(12):1072-1079. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist‐Led Antimicrobial Stewardship

Inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients is a well‐recognized driver for the development of drug‐resistant organisms and antimicrobial‐related complications such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).[1, 2] Infection with C difficile affects nearly 500,000 people annually resulting in higher healthcare expenditures, longer lengths of hospital stay, and nearly 15,000 deaths.[3] Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that a 30% reduction in the use of broad‐spectrum antimicrobials, or a 5% reduction in the proportion of hospitalized patients receiving antimicrobials, could equate to a 26% reduction in CDI.[4] It is estimated that up to 50% of antimicrobial use in the hospital setting may be inappropriate.[5]

Since the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America published guidelines for developing formal, hospital‐based antimicrobial stewardship programs in 2007, stewardship practices have been adapted by frontline providers to fit day‐to‐day inpatient care.[5] A recent review by Hamilton et al. described several studies in which stewardship practices were imbedded into daily workflows by way of checklists, education reminders, and periodic review of antimicrobial usage, as well as a multicenter pilot of point‐of‐care stewardship interventions successfully implemented by various providers including nursing, pharmacists, and hospitalists.[6]

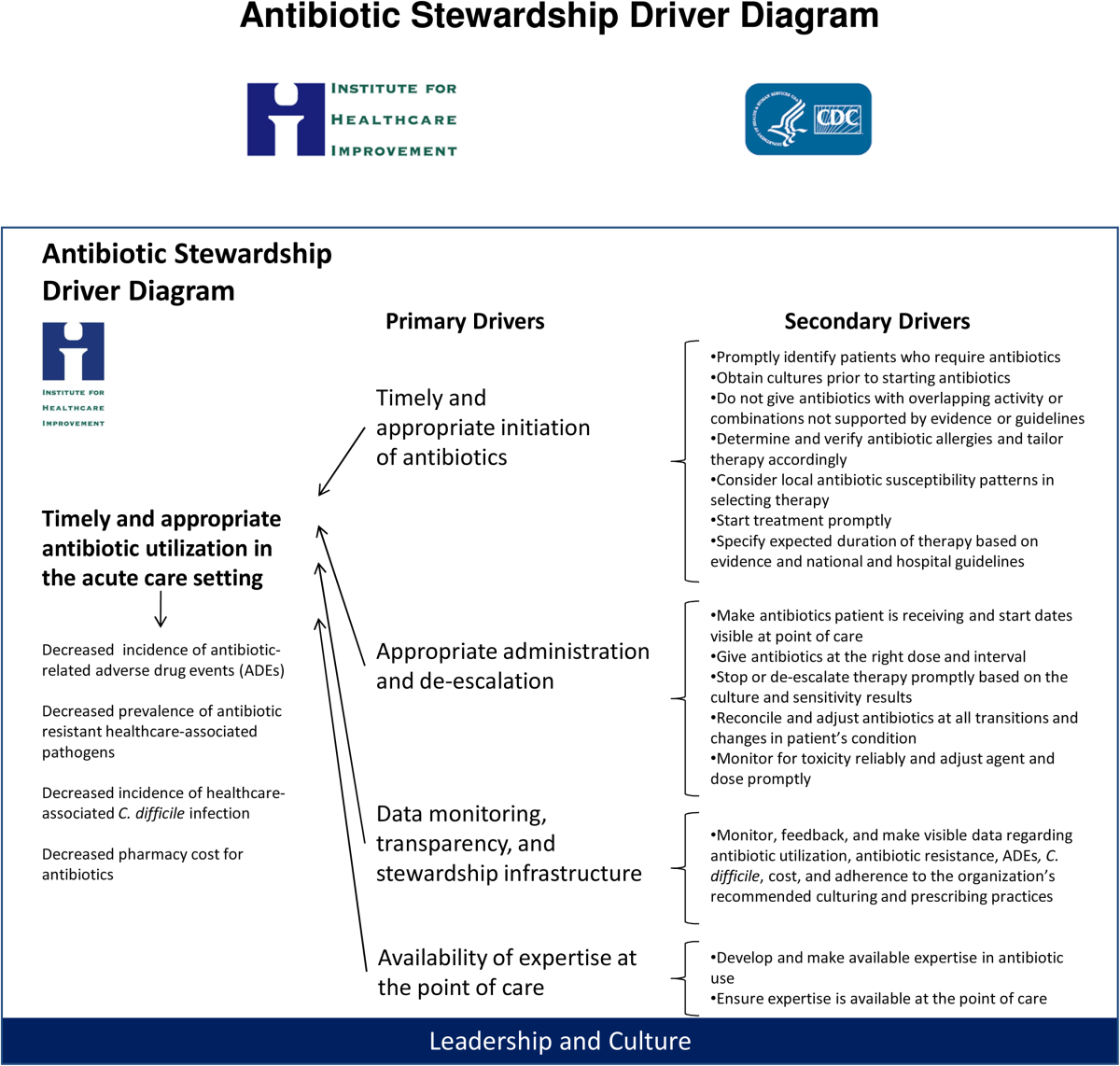

In response to the CDC's 2010 Get Smart for Healthcare campaign, which focused on stemming antimicrobial resistance and improving antimicrobial use, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), in partnership with the CDC, brought together experts in the field to identify practical and feasible target practices for hospital‐based stewardship and created a Driver Diagram to guide implementation efforts (Figure 1). Rohde et al. described the initial pilot testing of these practices, the decision to more actively engage frontline providers, and the 3 key strategies identified as high‐yield improvement targets: enhancing the visibility of antimicrobial use at the point of care, creating easily accessible antimicrobial guidelines for common infections, and the implementation of a 72‐hour timeout after initiation of antimicrobials.[7]

In this article, we describe how, in partnership with the IHI and the CDC, the hospital medicine programs at 5 diverse hospitals iteratively tested these 3 strategies with a goal of identifying the barriers and facilitators to effective hospitalist‐led antimicrobial stewardship.

METHODS

Representatives from 5 hospital medicine programs, IHI, and the CDC attended a kick‐off meeting at the CDC in November 2012 to discuss the 3 proposed strategies, examples of prior testing, and ideas for implementation. Each hospitalist provided a high‐level summary of the current state of stewardship efforts at their respective institutions, identified possible future states related to the improvement strategies, and anticipated problems in achieving them. The 3 key strategies are described below.

Improved Documentation/Visibility at Points of Care

Making antimicrobial indication, day of therapy, and anticipated duration transparent in the medical record was the targeted improvement strategy to avoid unnecessary antimicrobial days that can result from provider uncertainty, particularly during patient handoffs. Daily hospitalist documentation was identified as a vehicle through which these aspects of antimicrobial use could be effectively communicated and propagated from provider to provider.

Stewardship educational sessions and/or awareness campaigns were hospitalist led, and were accompanied by follow‐up reminders in the forms of emails, texts, flyers, or conferences. Infectious disease physicians were not directly involved in education but were available for consultation if needed.

Improved Guideline Clarity and Accessibility

Enhancing the availability of guidelines for frequently encountered infections and clarifying key guideline recommendations such as treatment duration were identified as the improvement strategies to help make treatment regimens more appropriate and consistent across providers.

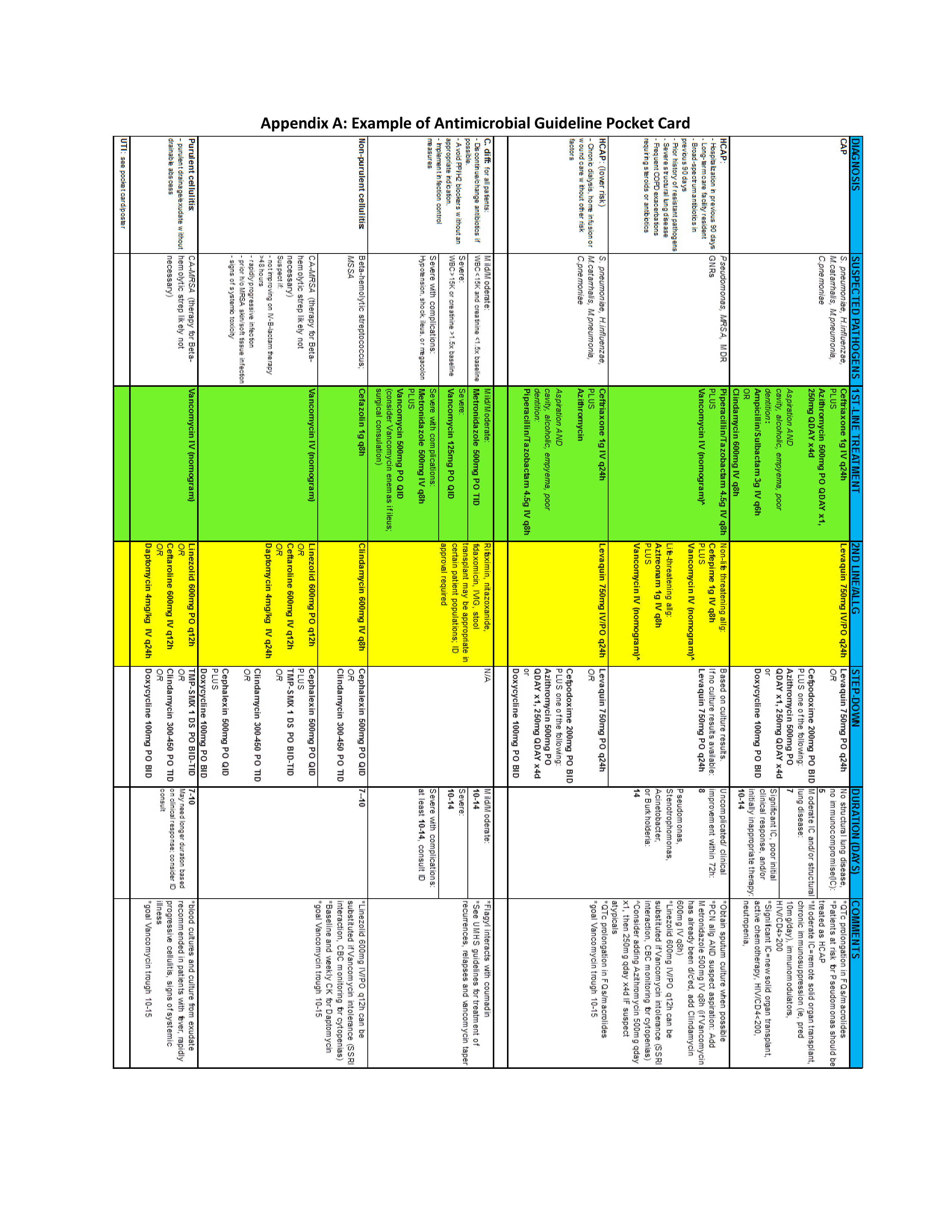

Interventions included designing simplified pocket cards for commonly encountered infections, (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article), collaborating with infectious disease physicians on guideline development, and dissemination through email, smartphone, and wall flyers, and creation of a continuous medical education module focused on stewardship practices.

72‐Hour Antimicrobial Timeout

The 72‐hour antimicrobial timeout required that hospitalists routinely reassess antimicrobial use 72 hours following antimicrobial initiation, a time when most pertinent culture data had returned. Hospitalists partnered with clinical pharmacists at all sites, and addressed the following questions during each timeout: (1) Does the patient have a condition that requires continued use of antimicrobials? (2) Can the current antimicrobial regimen be tailored based on culture data? (3) What is the anticipated treatment duration? A variety of modifications occurred during timeouts, including broadening or narrowing the antimicrobial regimen based on culture data, switching to an oral antimicrobial, adjusting dose or frequency based on patient‐specific factors, as well as discontinuation of antimicrobials. Following the initial timeout, further adjustments were made as the clinical situation dictated; intermittent partnered timeouts continued during a patient's hospitalization on an individualized basis. Hospitalists were encouraged to independently review new diagnostic information daily and make changes as needed outside the dedicated time‐out sessions. All decisions to adjust antimicrobial regimens were provider driven; no hospitals employed automated antimicrobial discontinuation without provider input.

Implementation and Evaluation

Each site was tasked with conducting small tests of change aimed at implementing at least 1, and ideally all 3 strategies. Small, reasonably achievable interventions were preferred to large hospital‐wide initiatives so that key barriers and facilitators to the change could be quickly identified and addressed.

Methods of data collection varied across institutions and included anonymous physician survey, face‐to‐face physician interviews, and medical record review. Evaluations of hospital‐specific interventions utilized convenience samples to obtain real time, actionable data. Postintervention data were distributed through biweekly calls and compiled at the conclusion of the project. Barriers and facilitators of hospitalist‐centered antimicrobial stewardship collected over the course of the project were reviewed and used to identify common themes.

RESULTS

Participating hospitals included 1 community nonteaching hospital, 2 community teaching hospitals, and 2 academic medical centers. All hospitals used computerized order entry and had prior quality improvement experience; 4 out of 5 hospitals used electronic medical records. Postintervention data on antimicrobial documentation and timeouts were compiled, shared, and successes identified. For example, 2 hospitals saw an increase in complete antimicrobial documentation from 4% and 8% to 51% and 65%, respectively, of medical records reviewed over a 3‐month period. Additionally, cumulative timeout data across all hospitals showed that out of 726 antimicrobial timeouts evaluated, optimization or discontinuation occurred 218 times or 30% of the time.

Each site's key implementation barriers and facilitators were collected. Examples were compiled and common themes emerged (Table 1).

| ||

| Barriers: What impediments did we experience during our stewardship project? | Schedule and practice variability | Physician variability in structure of antimicrobial documentation |

| Prescribing etiquette: it's difficult to change course of treatment plan started by a colleague | ||

| Competing schedule demands of hospitalist and pharmacist | ||

| Skepticism of antimicrobial stewardship importance | Perception of incorporating stewardship practices into daily work as time consuming | |

| Improvement project fatigue from competing quality improvement initiatives | ||

| Unclear leadership buy‐in | ||

| Focusing too broadly | Choosing large initial interventions, which take significant time/effort to complete and quantify | |

| Setting unrealistic expectations (eg, expecting perfect adherence to documentation, guidelines, or timeout) | ||

| Facilitators: What countermeasures did we target to overcome barriers? | Engage the hospitalists | Establish a core part of the hospitalist group as stewardship champions |

| Speak 1‐on‐1 to colleagues about specific goals and ways to achieve them | ||

| Establish buy‐in from leadership | ||

| Encourage participation from a multidisciplinary team (eg, bedside nursing, clinical pharmacists) | ||

| Collect real time data and feedback | Utilize a data collection tool if possible/engage hospital coders to identify appropriate diagnoses | |

| Define your question and identify baseline data prior to intervention | ||

| Give rapid cycle feedback to colleagues that can impact antimicrobial prescribing in real time | ||

| Recognize and reward high performers | ||

| Limit scope | Start with small, quickly implementable interventions | |

| Identify interventions that are easy to integrate into hospitalist workflow | ||

DISCUSSION

We successfully brought together hospitalists from diverse institutions to undertake small tests of change aimed at 3 key antimicrobial use improvement strategies. Following our interventions, significant improvement in antimicrobial documentation occurred at 2 institutions focusing on this improvement strategy, and 72‐hour timeouts performed across all hospitals tailored antimicrobial use in 30% of the sessions. Through frequent collaborative discussions and information sharing, we were able to identify common barriers and facilitators to hospitalist‐centered stewardship efforts.

Each participating hospital medicine program noticed a gradual shift in thinking among their colleagues, from initial skepticism about embedding stewardship within their daily workflow, to general acceptance that it was a worthwhile and meaningful endeavor. We posited that this transition in belief and behavior evolved for several reasons. First, each group was educated about their own, personal prescribing practices from the outset rather than presenting abstract data. This allowed for ownership of the problem and buy‐in to improve it. Second, participants were able to experience the benefits at an individual level while the interventions were ongoing (eg, having other providers reciprocate structured documentation during patient handoffs, making antimicrobial plans clearer), reinforcing the achievability of stewardship practices within each group. Additionally, we focused on making small, manageable interventions that did not seem disruptive to hospitalists' daily workflow. For example, 1 group instituted antimicrobial timeouts during preexisting multidisciplinary rounds with clinical pharmacists. Last, project champions had both leadership and frontline roles within their groups and set the example for stewardship practices, which conveyed that this was a priority at the leadership level. These findings are in line with those of Charani et al., who evaluated behavior change strategies that influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care. The authors found that behavioral determinants and social norms strongly influence prescribing practices in acute care, and that antimicrobial stewardship improvement projects should account for these influences.[8]

We also identified several barriers to antimicrobial stewardship implementation (Table 1) and proposed measures to address these barriers in future improvement efforts. For example, hospital medicine programs without a preexisting clinical pharmacy partnership asked hospitalist leadership for more direct clinical pharmacy involvement, recognizing the importance of a physician‐pharmacy alliance for stewardship efforts. To more effectively embed antimicrobial stewardship into daily routine, several hospitalists suggested standardized order sets for commonly encountered infections, as well as routine feedback on prescribing practices. Furthermore, although our simplified antimicrobial guideline pocket card enhanced access to this information, several colleagues suggested a smart phone application that would make access even easier and less cumbersome. Last, given the concern about the sustainability of antimicrobial stewardship initiatives, we recommended periodic reminders, random medical record review, and re‐education if necessary on our 3 strategies and their purpose.

Our study is not without limitations. Each participating hospitalist group enacted hospital‐specific interventions based on individual hospitalist program needs and goals, and although there was collective discussion, no group was tasked to undertake another group's initiative, thereby limiting generalizability. We did, however, identify common facilitators that could be adapted to a wide variety of hospitalist programs. We also note that our 3 main strategies were included in a recent review of quality indicators for measuring the success of antimicrobial stewardship programs; thus, although details of individual practice may vary, in principle these concepts can help identify areas for improvement within each unique stewardship program.[9] Importantly, we were unable to evaluate the impact of the 3 key improvement strategies on important clinical outcomes such as overall antimicrobial use, complications including CDI, and cost. However, others have found that improvement strategies similar to our 3 key processes are associated with meaningful improvements in clinical outcomes as well as reductions in healthcare costs.[10, 11] Last, long‐ term impact and sustainability were not evaluated. By choosing interventions that were viewed by frontline providers as valuable and attainable, however, we feel that each group will likely continue current practices beyond the initial evaluation timeframe.

Although these 5 hospitalist groups were able to successfully implement several aspects of the 3 key improvement strategies, we recognize that this is only the first step. Further effort is needed to quantify the impact of these improvement efforts on objective patient outcomes such as readmissions, length of stay, and antimicrobial‐related complications, which will better inform our local and national leaders on the inherent clinical and financial gains associated with hospitalist‐led stewardship work. Finally, creative ways to better integrate stewardship activities into existing provider workflows (eg, decision support and automation) will further accelerate improvement efforts.

In summary, hospitalists at 5 diverse institutions successfully implemented key antimicrobial improvement strategies and identified important implementation facilitators and barriers. Future efforts at hospitalist‐led stewardship should focus on strategies to scale‐up interventions and evaluate their impact on clinical outcomes and cost.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Latoya Kuhn, MPH, for her assistance with statistical analyses. We also thank the clinical pharmacists at each institution for their partnership in stewardship efforts: Patrick Arnold, PharmD, and Matthew Tupps, PharmD, MHA, from University of Michigan Hospital and Health System; and Roland Tam, PharmD, from Emory Johns Creek Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Flanders reports consulting fees or honoraria from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has provided consultancy to the Society of Hospital Medicine, has served as a reviewer for expert testimony, received honoraria as a visiting lecturer to various hospitals, and has received royalties from publisher John Wiley & Sons. He has also received grant funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Ko reports consultancy for the American Hospital Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine involving work with catheter‐associated urinary tract infections. Ms. Jacobsen reports grant funding from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Rosenberg reports consultancy for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. The funding source for this collaborative was through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding was provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases, and the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion/Office of the Director. Avaris Concepts served as the prime contractor and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the subcontractor for the initiative. The findings and conclusions in this report represent the views of the authors and might not reflect the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008;6(5):751–763.

- , , , et al. Hospital and societal costs of antimicrobial‐resistant infections in a Chicago teaching hospital: implications for antibiotic stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1175–1184.

- , , , et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825–834.

- , , , et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194–200.

- , , , et al.; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177.

- , , , et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters Program. Point‐of‐prescription interventions to improve antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(8):1252–1258.

- , , . Role of the hospitalist in antimicrobial stewardship: a review of work completed and description of a multisite collaborative. Clin Ther. 2013;35(6):751–757.

- , , , et al. Behavior change strategies to influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):651–662.

- , , , , . Quality indicators to measure appropriate antibiotic use in hospitalized adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(2):281–291.

- , . Application of antimicrobial stewardship to optimise management of community acquired pneumonia. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(7):775–783.

- , , , et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD003543.

Inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients is a well‐recognized driver for the development of drug‐resistant organisms and antimicrobial‐related complications such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).[1, 2] Infection with C difficile affects nearly 500,000 people annually resulting in higher healthcare expenditures, longer lengths of hospital stay, and nearly 15,000 deaths.[3] Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that a 30% reduction in the use of broad‐spectrum antimicrobials, or a 5% reduction in the proportion of hospitalized patients receiving antimicrobials, could equate to a 26% reduction in CDI.[4] It is estimated that up to 50% of antimicrobial use in the hospital setting may be inappropriate.[5]

Since the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America published guidelines for developing formal, hospital‐based antimicrobial stewardship programs in 2007, stewardship practices have been adapted by frontline providers to fit day‐to‐day inpatient care.[5] A recent review by Hamilton et al. described several studies in which stewardship practices were imbedded into daily workflows by way of checklists, education reminders, and periodic review of antimicrobial usage, as well as a multicenter pilot of point‐of‐care stewardship interventions successfully implemented by various providers including nursing, pharmacists, and hospitalists.[6]

In response to the CDC's 2010 Get Smart for Healthcare campaign, which focused on stemming antimicrobial resistance and improving antimicrobial use, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), in partnership with the CDC, brought together experts in the field to identify practical and feasible target practices for hospital‐based stewardship and created a Driver Diagram to guide implementation efforts (Figure 1). Rohde et al. described the initial pilot testing of these practices, the decision to more actively engage frontline providers, and the 3 key strategies identified as high‐yield improvement targets: enhancing the visibility of antimicrobial use at the point of care, creating easily accessible antimicrobial guidelines for common infections, and the implementation of a 72‐hour timeout after initiation of antimicrobials.[7]

In this article, we describe how, in partnership with the IHI and the CDC, the hospital medicine programs at 5 diverse hospitals iteratively tested these 3 strategies with a goal of identifying the barriers and facilitators to effective hospitalist‐led antimicrobial stewardship.

METHODS

Representatives from 5 hospital medicine programs, IHI, and the CDC attended a kick‐off meeting at the CDC in November 2012 to discuss the 3 proposed strategies, examples of prior testing, and ideas for implementation. Each hospitalist provided a high‐level summary of the current state of stewardship efforts at their respective institutions, identified possible future states related to the improvement strategies, and anticipated problems in achieving them. The 3 key strategies are described below.

Improved Documentation/Visibility at Points of Care

Making antimicrobial indication, day of therapy, and anticipated duration transparent in the medical record was the targeted improvement strategy to avoid unnecessary antimicrobial days that can result from provider uncertainty, particularly during patient handoffs. Daily hospitalist documentation was identified as a vehicle through which these aspects of antimicrobial use could be effectively communicated and propagated from provider to provider.

Stewardship educational sessions and/or awareness campaigns were hospitalist led, and were accompanied by follow‐up reminders in the forms of emails, texts, flyers, or conferences. Infectious disease physicians were not directly involved in education but were available for consultation if needed.

Improved Guideline Clarity and Accessibility

Enhancing the availability of guidelines for frequently encountered infections and clarifying key guideline recommendations such as treatment duration were identified as the improvement strategies to help make treatment regimens more appropriate and consistent across providers.

Interventions included designing simplified pocket cards for commonly encountered infections, (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article), collaborating with infectious disease physicians on guideline development, and dissemination through email, smartphone, and wall flyers, and creation of a continuous medical education module focused on stewardship practices.

72‐Hour Antimicrobial Timeout

The 72‐hour antimicrobial timeout required that hospitalists routinely reassess antimicrobial use 72 hours following antimicrobial initiation, a time when most pertinent culture data had returned. Hospitalists partnered with clinical pharmacists at all sites, and addressed the following questions during each timeout: (1) Does the patient have a condition that requires continued use of antimicrobials? (2) Can the current antimicrobial regimen be tailored based on culture data? (3) What is the anticipated treatment duration? A variety of modifications occurred during timeouts, including broadening or narrowing the antimicrobial regimen based on culture data, switching to an oral antimicrobial, adjusting dose or frequency based on patient‐specific factors, as well as discontinuation of antimicrobials. Following the initial timeout, further adjustments were made as the clinical situation dictated; intermittent partnered timeouts continued during a patient's hospitalization on an individualized basis. Hospitalists were encouraged to independently review new diagnostic information daily and make changes as needed outside the dedicated time‐out sessions. All decisions to adjust antimicrobial regimens were provider driven; no hospitals employed automated antimicrobial discontinuation without provider input.

Implementation and Evaluation

Each site was tasked with conducting small tests of change aimed at implementing at least 1, and ideally all 3 strategies. Small, reasonably achievable interventions were preferred to large hospital‐wide initiatives so that key barriers and facilitators to the change could be quickly identified and addressed.

Methods of data collection varied across institutions and included anonymous physician survey, face‐to‐face physician interviews, and medical record review. Evaluations of hospital‐specific interventions utilized convenience samples to obtain real time, actionable data. Postintervention data were distributed through biweekly calls and compiled at the conclusion of the project. Barriers and facilitators of hospitalist‐centered antimicrobial stewardship collected over the course of the project were reviewed and used to identify common themes.

RESULTS

Participating hospitals included 1 community nonteaching hospital, 2 community teaching hospitals, and 2 academic medical centers. All hospitals used computerized order entry and had prior quality improvement experience; 4 out of 5 hospitals used electronic medical records. Postintervention data on antimicrobial documentation and timeouts were compiled, shared, and successes identified. For example, 2 hospitals saw an increase in complete antimicrobial documentation from 4% and 8% to 51% and 65%, respectively, of medical records reviewed over a 3‐month period. Additionally, cumulative timeout data across all hospitals showed that out of 726 antimicrobial timeouts evaluated, optimization or discontinuation occurred 218 times or 30% of the time.

Each site's key implementation barriers and facilitators were collected. Examples were compiled and common themes emerged (Table 1).

| ||

| Barriers: What impediments did we experience during our stewardship project? | Schedule and practice variability | Physician variability in structure of antimicrobial documentation |

| Prescribing etiquette: it's difficult to change course of treatment plan started by a colleague | ||

| Competing schedule demands of hospitalist and pharmacist | ||

| Skepticism of antimicrobial stewardship importance | Perception of incorporating stewardship practices into daily work as time consuming | |

| Improvement project fatigue from competing quality improvement initiatives | ||

| Unclear leadership buy‐in | ||

| Focusing too broadly | Choosing large initial interventions, which take significant time/effort to complete and quantify | |

| Setting unrealistic expectations (eg, expecting perfect adherence to documentation, guidelines, or timeout) | ||

| Facilitators: What countermeasures did we target to overcome barriers? | Engage the hospitalists | Establish a core part of the hospitalist group as stewardship champions |

| Speak 1‐on‐1 to colleagues about specific goals and ways to achieve them | ||

| Establish buy‐in from leadership | ||

| Encourage participation from a multidisciplinary team (eg, bedside nursing, clinical pharmacists) | ||

| Collect real time data and feedback | Utilize a data collection tool if possible/engage hospital coders to identify appropriate diagnoses | |

| Define your question and identify baseline data prior to intervention | ||

| Give rapid cycle feedback to colleagues that can impact antimicrobial prescribing in real time | ||

| Recognize and reward high performers | ||

| Limit scope | Start with small, quickly implementable interventions | |

| Identify interventions that are easy to integrate into hospitalist workflow | ||

DISCUSSION

We successfully brought together hospitalists from diverse institutions to undertake small tests of change aimed at 3 key antimicrobial use improvement strategies. Following our interventions, significant improvement in antimicrobial documentation occurred at 2 institutions focusing on this improvement strategy, and 72‐hour timeouts performed across all hospitals tailored antimicrobial use in 30% of the sessions. Through frequent collaborative discussions and information sharing, we were able to identify common barriers and facilitators to hospitalist‐centered stewardship efforts.

Each participating hospital medicine program noticed a gradual shift in thinking among their colleagues, from initial skepticism about embedding stewardship within their daily workflow, to general acceptance that it was a worthwhile and meaningful endeavor. We posited that this transition in belief and behavior evolved for several reasons. First, each group was educated about their own, personal prescribing practices from the outset rather than presenting abstract data. This allowed for ownership of the problem and buy‐in to improve it. Second, participants were able to experience the benefits at an individual level while the interventions were ongoing (eg, having other providers reciprocate structured documentation during patient handoffs, making antimicrobial plans clearer), reinforcing the achievability of stewardship practices within each group. Additionally, we focused on making small, manageable interventions that did not seem disruptive to hospitalists' daily workflow. For example, 1 group instituted antimicrobial timeouts during preexisting multidisciplinary rounds with clinical pharmacists. Last, project champions had both leadership and frontline roles within their groups and set the example for stewardship practices, which conveyed that this was a priority at the leadership level. These findings are in line with those of Charani et al., who evaluated behavior change strategies that influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care. The authors found that behavioral determinants and social norms strongly influence prescribing practices in acute care, and that antimicrobial stewardship improvement projects should account for these influences.[8]

We also identified several barriers to antimicrobial stewardship implementation (Table 1) and proposed measures to address these barriers in future improvement efforts. For example, hospital medicine programs without a preexisting clinical pharmacy partnership asked hospitalist leadership for more direct clinical pharmacy involvement, recognizing the importance of a physician‐pharmacy alliance for stewardship efforts. To more effectively embed antimicrobial stewardship into daily routine, several hospitalists suggested standardized order sets for commonly encountered infections, as well as routine feedback on prescribing practices. Furthermore, although our simplified antimicrobial guideline pocket card enhanced access to this information, several colleagues suggested a smart phone application that would make access even easier and less cumbersome. Last, given the concern about the sustainability of antimicrobial stewardship initiatives, we recommended periodic reminders, random medical record review, and re‐education if necessary on our 3 strategies and their purpose.

Our study is not without limitations. Each participating hospitalist group enacted hospital‐specific interventions based on individual hospitalist program needs and goals, and although there was collective discussion, no group was tasked to undertake another group's initiative, thereby limiting generalizability. We did, however, identify common facilitators that could be adapted to a wide variety of hospitalist programs. We also note that our 3 main strategies were included in a recent review of quality indicators for measuring the success of antimicrobial stewardship programs; thus, although details of individual practice may vary, in principle these concepts can help identify areas for improvement within each unique stewardship program.[9] Importantly, we were unable to evaluate the impact of the 3 key improvement strategies on important clinical outcomes such as overall antimicrobial use, complications including CDI, and cost. However, others have found that improvement strategies similar to our 3 key processes are associated with meaningful improvements in clinical outcomes as well as reductions in healthcare costs.[10, 11] Last, long‐ term impact and sustainability were not evaluated. By choosing interventions that were viewed by frontline providers as valuable and attainable, however, we feel that each group will likely continue current practices beyond the initial evaluation timeframe.

Although these 5 hospitalist groups were able to successfully implement several aspects of the 3 key improvement strategies, we recognize that this is only the first step. Further effort is needed to quantify the impact of these improvement efforts on objective patient outcomes such as readmissions, length of stay, and antimicrobial‐related complications, which will better inform our local and national leaders on the inherent clinical and financial gains associated with hospitalist‐led stewardship work. Finally, creative ways to better integrate stewardship activities into existing provider workflows (eg, decision support and automation) will further accelerate improvement efforts.

In summary, hospitalists at 5 diverse institutions successfully implemented key antimicrobial improvement strategies and identified important implementation facilitators and barriers. Future efforts at hospitalist‐led stewardship should focus on strategies to scale‐up interventions and evaluate their impact on clinical outcomes and cost.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Latoya Kuhn, MPH, for her assistance with statistical analyses. We also thank the clinical pharmacists at each institution for their partnership in stewardship efforts: Patrick Arnold, PharmD, and Matthew Tupps, PharmD, MHA, from University of Michigan Hospital and Health System; and Roland Tam, PharmD, from Emory Johns Creek Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Flanders reports consulting fees or honoraria from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has provided consultancy to the Society of Hospital Medicine, has served as a reviewer for expert testimony, received honoraria as a visiting lecturer to various hospitals, and has received royalties from publisher John Wiley & Sons. He has also received grant funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Ko reports consultancy for the American Hospital Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine involving work with catheter‐associated urinary tract infections. Ms. Jacobsen reports grant funding from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Rosenberg reports consultancy for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. The funding source for this collaborative was through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding was provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases, and the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion/Office of the Director. Avaris Concepts served as the prime contractor and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the subcontractor for the initiative. The findings and conclusions in this report represent the views of the authors and might not reflect the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitalized patients is a well‐recognized driver for the development of drug‐resistant organisms and antimicrobial‐related complications such as Clostridium difficile infection (CDI).[1, 2] Infection with C difficile affects nearly 500,000 people annually resulting in higher healthcare expenditures, longer lengths of hospital stay, and nearly 15,000 deaths.[3] Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that a 30% reduction in the use of broad‐spectrum antimicrobials, or a 5% reduction in the proportion of hospitalized patients receiving antimicrobials, could equate to a 26% reduction in CDI.[4] It is estimated that up to 50% of antimicrobial use in the hospital setting may be inappropriate.[5]

Since the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America published guidelines for developing formal, hospital‐based antimicrobial stewardship programs in 2007, stewardship practices have been adapted by frontline providers to fit day‐to‐day inpatient care.[5] A recent review by Hamilton et al. described several studies in which stewardship practices were imbedded into daily workflows by way of checklists, education reminders, and periodic review of antimicrobial usage, as well as a multicenter pilot of point‐of‐care stewardship interventions successfully implemented by various providers including nursing, pharmacists, and hospitalists.[6]

In response to the CDC's 2010 Get Smart for Healthcare campaign, which focused on stemming antimicrobial resistance and improving antimicrobial use, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), in partnership with the CDC, brought together experts in the field to identify practical and feasible target practices for hospital‐based stewardship and created a Driver Diagram to guide implementation efforts (Figure 1). Rohde et al. described the initial pilot testing of these practices, the decision to more actively engage frontline providers, and the 3 key strategies identified as high‐yield improvement targets: enhancing the visibility of antimicrobial use at the point of care, creating easily accessible antimicrobial guidelines for common infections, and the implementation of a 72‐hour timeout after initiation of antimicrobials.[7]

In this article, we describe how, in partnership with the IHI and the CDC, the hospital medicine programs at 5 diverse hospitals iteratively tested these 3 strategies with a goal of identifying the barriers and facilitators to effective hospitalist‐led antimicrobial stewardship.

METHODS

Representatives from 5 hospital medicine programs, IHI, and the CDC attended a kick‐off meeting at the CDC in November 2012 to discuss the 3 proposed strategies, examples of prior testing, and ideas for implementation. Each hospitalist provided a high‐level summary of the current state of stewardship efforts at their respective institutions, identified possible future states related to the improvement strategies, and anticipated problems in achieving them. The 3 key strategies are described below.

Improved Documentation/Visibility at Points of Care

Making antimicrobial indication, day of therapy, and anticipated duration transparent in the medical record was the targeted improvement strategy to avoid unnecessary antimicrobial days that can result from provider uncertainty, particularly during patient handoffs. Daily hospitalist documentation was identified as a vehicle through which these aspects of antimicrobial use could be effectively communicated and propagated from provider to provider.

Stewardship educational sessions and/or awareness campaigns were hospitalist led, and were accompanied by follow‐up reminders in the forms of emails, texts, flyers, or conferences. Infectious disease physicians were not directly involved in education but were available for consultation if needed.

Improved Guideline Clarity and Accessibility

Enhancing the availability of guidelines for frequently encountered infections and clarifying key guideline recommendations such as treatment duration were identified as the improvement strategies to help make treatment regimens more appropriate and consistent across providers.

Interventions included designing simplified pocket cards for commonly encountered infections, (see Supporting Information, Appendix A, in the online version of this article), collaborating with infectious disease physicians on guideline development, and dissemination through email, smartphone, and wall flyers, and creation of a continuous medical education module focused on stewardship practices.

72‐Hour Antimicrobial Timeout

The 72‐hour antimicrobial timeout required that hospitalists routinely reassess antimicrobial use 72 hours following antimicrobial initiation, a time when most pertinent culture data had returned. Hospitalists partnered with clinical pharmacists at all sites, and addressed the following questions during each timeout: (1) Does the patient have a condition that requires continued use of antimicrobials? (2) Can the current antimicrobial regimen be tailored based on culture data? (3) What is the anticipated treatment duration? A variety of modifications occurred during timeouts, including broadening or narrowing the antimicrobial regimen based on culture data, switching to an oral antimicrobial, adjusting dose or frequency based on patient‐specific factors, as well as discontinuation of antimicrobials. Following the initial timeout, further adjustments were made as the clinical situation dictated; intermittent partnered timeouts continued during a patient's hospitalization on an individualized basis. Hospitalists were encouraged to independently review new diagnostic information daily and make changes as needed outside the dedicated time‐out sessions. All decisions to adjust antimicrobial regimens were provider driven; no hospitals employed automated antimicrobial discontinuation without provider input.

Implementation and Evaluation

Each site was tasked with conducting small tests of change aimed at implementing at least 1, and ideally all 3 strategies. Small, reasonably achievable interventions were preferred to large hospital‐wide initiatives so that key barriers and facilitators to the change could be quickly identified and addressed.

Methods of data collection varied across institutions and included anonymous physician survey, face‐to‐face physician interviews, and medical record review. Evaluations of hospital‐specific interventions utilized convenience samples to obtain real time, actionable data. Postintervention data were distributed through biweekly calls and compiled at the conclusion of the project. Barriers and facilitators of hospitalist‐centered antimicrobial stewardship collected over the course of the project were reviewed and used to identify common themes.

RESULTS

Participating hospitals included 1 community nonteaching hospital, 2 community teaching hospitals, and 2 academic medical centers. All hospitals used computerized order entry and had prior quality improvement experience; 4 out of 5 hospitals used electronic medical records. Postintervention data on antimicrobial documentation and timeouts were compiled, shared, and successes identified. For example, 2 hospitals saw an increase in complete antimicrobial documentation from 4% and 8% to 51% and 65%, respectively, of medical records reviewed over a 3‐month period. Additionally, cumulative timeout data across all hospitals showed that out of 726 antimicrobial timeouts evaluated, optimization or discontinuation occurred 218 times or 30% of the time.

Each site's key implementation barriers and facilitators were collected. Examples were compiled and common themes emerged (Table 1).

| ||

| Barriers: What impediments did we experience during our stewardship project? | Schedule and practice variability | Physician variability in structure of antimicrobial documentation |

| Prescribing etiquette: it's difficult to change course of treatment plan started by a colleague | ||

| Competing schedule demands of hospitalist and pharmacist | ||

| Skepticism of antimicrobial stewardship importance | Perception of incorporating stewardship practices into daily work as time consuming | |

| Improvement project fatigue from competing quality improvement initiatives | ||

| Unclear leadership buy‐in | ||

| Focusing too broadly | Choosing large initial interventions, which take significant time/effort to complete and quantify | |

| Setting unrealistic expectations (eg, expecting perfect adherence to documentation, guidelines, or timeout) | ||

| Facilitators: What countermeasures did we target to overcome barriers? | Engage the hospitalists | Establish a core part of the hospitalist group as stewardship champions |

| Speak 1‐on‐1 to colleagues about specific goals and ways to achieve them | ||

| Establish buy‐in from leadership | ||

| Encourage participation from a multidisciplinary team (eg, bedside nursing, clinical pharmacists) | ||

| Collect real time data and feedback | Utilize a data collection tool if possible/engage hospital coders to identify appropriate diagnoses | |

| Define your question and identify baseline data prior to intervention | ||

| Give rapid cycle feedback to colleagues that can impact antimicrobial prescribing in real time | ||

| Recognize and reward high performers | ||

| Limit scope | Start with small, quickly implementable interventions | |

| Identify interventions that are easy to integrate into hospitalist workflow | ||

DISCUSSION

We successfully brought together hospitalists from diverse institutions to undertake small tests of change aimed at 3 key antimicrobial use improvement strategies. Following our interventions, significant improvement in antimicrobial documentation occurred at 2 institutions focusing on this improvement strategy, and 72‐hour timeouts performed across all hospitals tailored antimicrobial use in 30% of the sessions. Through frequent collaborative discussions and information sharing, we were able to identify common barriers and facilitators to hospitalist‐centered stewardship efforts.

Each participating hospital medicine program noticed a gradual shift in thinking among their colleagues, from initial skepticism about embedding stewardship within their daily workflow, to general acceptance that it was a worthwhile and meaningful endeavor. We posited that this transition in belief and behavior evolved for several reasons. First, each group was educated about their own, personal prescribing practices from the outset rather than presenting abstract data. This allowed for ownership of the problem and buy‐in to improve it. Second, participants were able to experience the benefits at an individual level while the interventions were ongoing (eg, having other providers reciprocate structured documentation during patient handoffs, making antimicrobial plans clearer), reinforcing the achievability of stewardship practices within each group. Additionally, we focused on making small, manageable interventions that did not seem disruptive to hospitalists' daily workflow. For example, 1 group instituted antimicrobial timeouts during preexisting multidisciplinary rounds with clinical pharmacists. Last, project champions had both leadership and frontline roles within their groups and set the example for stewardship practices, which conveyed that this was a priority at the leadership level. These findings are in line with those of Charani et al., who evaluated behavior change strategies that influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care. The authors found that behavioral determinants and social norms strongly influence prescribing practices in acute care, and that antimicrobial stewardship improvement projects should account for these influences.[8]

We also identified several barriers to antimicrobial stewardship implementation (Table 1) and proposed measures to address these barriers in future improvement efforts. For example, hospital medicine programs without a preexisting clinical pharmacy partnership asked hospitalist leadership for more direct clinical pharmacy involvement, recognizing the importance of a physician‐pharmacy alliance for stewardship efforts. To more effectively embed antimicrobial stewardship into daily routine, several hospitalists suggested standardized order sets for commonly encountered infections, as well as routine feedback on prescribing practices. Furthermore, although our simplified antimicrobial guideline pocket card enhanced access to this information, several colleagues suggested a smart phone application that would make access even easier and less cumbersome. Last, given the concern about the sustainability of antimicrobial stewardship initiatives, we recommended periodic reminders, random medical record review, and re‐education if necessary on our 3 strategies and their purpose.

Our study is not without limitations. Each participating hospitalist group enacted hospital‐specific interventions based on individual hospitalist program needs and goals, and although there was collective discussion, no group was tasked to undertake another group's initiative, thereby limiting generalizability. We did, however, identify common facilitators that could be adapted to a wide variety of hospitalist programs. We also note that our 3 main strategies were included in a recent review of quality indicators for measuring the success of antimicrobial stewardship programs; thus, although details of individual practice may vary, in principle these concepts can help identify areas for improvement within each unique stewardship program.[9] Importantly, we were unable to evaluate the impact of the 3 key improvement strategies on important clinical outcomes such as overall antimicrobial use, complications including CDI, and cost. However, others have found that improvement strategies similar to our 3 key processes are associated with meaningful improvements in clinical outcomes as well as reductions in healthcare costs.[10, 11] Last, long‐ term impact and sustainability were not evaluated. By choosing interventions that were viewed by frontline providers as valuable and attainable, however, we feel that each group will likely continue current practices beyond the initial evaluation timeframe.

Although these 5 hospitalist groups were able to successfully implement several aspects of the 3 key improvement strategies, we recognize that this is only the first step. Further effort is needed to quantify the impact of these improvement efforts on objective patient outcomes such as readmissions, length of stay, and antimicrobial‐related complications, which will better inform our local and national leaders on the inherent clinical and financial gains associated with hospitalist‐led stewardship work. Finally, creative ways to better integrate stewardship activities into existing provider workflows (eg, decision support and automation) will further accelerate improvement efforts.

In summary, hospitalists at 5 diverse institutions successfully implemented key antimicrobial improvement strategies and identified important implementation facilitators and barriers. Future efforts at hospitalist‐led stewardship should focus on strategies to scale‐up interventions and evaluate their impact on clinical outcomes and cost.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Latoya Kuhn, MPH, for her assistance with statistical analyses. We also thank the clinical pharmacists at each institution for their partnership in stewardship efforts: Patrick Arnold, PharmD, and Matthew Tupps, PharmD, MHA, from University of Michigan Hospital and Health System; and Roland Tam, PharmD, from Emory Johns Creek Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Flanders reports consulting fees or honoraria from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has provided consultancy to the Society of Hospital Medicine, has served as a reviewer for expert testimony, received honoraria as a visiting lecturer to various hospitals, and has received royalties from publisher John Wiley & Sons. He has also received grant funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Ko reports consultancy for the American Hospital Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine involving work with catheter‐associated urinary tract infections. Ms. Jacobsen reports grant funding from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Dr. Rosenberg reports consultancy for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Forest Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. The funding source for this collaborative was through the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding was provided by the Department of Health and Human Services, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases, and the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion/Office of the Director. Avaris Concepts served as the prime contractor and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement as the subcontractor for the initiative. The findings and conclusions in this report represent the views of the authors and might not reflect the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Clinical and economic burden of antimicrobial resistance. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008;6(5):751–763.

- , , , et al. Hospital and societal costs of antimicrobial‐resistant infections in a Chicago teaching hospital: implications for antibiotic stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(8):1175–1184.

- , , , et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):825–834.

- , , , et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(9):194–200.