User login

Help your patient with hoarding disorder move the clutter to the curb

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

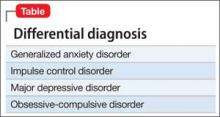

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.