User login

Topical hemostasis agents: Some tried and true, others too new

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- What clinical problem is this device or drug designed to address?

- Is the problem important clinically for the well-being of my patients?

- What do I know about the basic science and physiology of the problem?

- Are there data supporting improvement in clinical outcomes, or do the studies look only at surrogate endpoints?

- Has the drug or device been studied in gynecologic patients? Is it approved for use in this population?

- Is there evidence that the new technology is more effective, safer, or less expensive than products I use now?

The process of evaluation is critical for us—as advocates for individual patients and as stewards of the diminishing resources available to treat patients in the United States.

With these questions in mind, let’s look at a surgical problem for which there are many new and potentially exciting products being promoted to gynecologic surgeons: the need to achieve hemostasis.

Bleeding is a serious clinical problem during surgery—one that can have a major impact on the well-being of the patient. We generally use sutures and electrosurgical instruments—both bipolar and monopolar—to control major vessels. Topical hemostasis agents may be useful, however, in areas where generalized oozing is present, or where the application of energy may endanger vital structures.

Many products are available for use in these situations. Some are tried and true; others, new or unapproved for use in gynecologic surgery. Your assessment and selection of the optimal product should take into account 1) the cause of bleeding and 2) the mechanism of action of the product.

Surgical bleeding has one of two causes

Although the science of coagulation is complex, bleeding occurs, from a surgical perspective, because of either of two problems:

- failure to control significant arterial and venous sources

- failure of normal clotting functions, such as vasoconstriction; platelet activation and plugging ( FIGURE ); and activation of the coagulation cascade.

No topical or systemic agent adequately controls Problem #1. To address Problem #2, we have several choices to augment hemostasis, including thermal, chemical, and mechanical means. In addition, newer agents deliver additional coagulation-enhancing products such as platelets and thrombin to the operative site to supplement the patient’s natural clotting process.

FIGURE How a clot forms

Tried and true technologies

Because of long-standing experience with porcine gelatin, oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC), and microfibrillar collagen, the Food and Drug Administration recategorized them in 2002 as Class-II devices with a clear safety profile.

Porcine gelatin

This class of products (Gelfoam, Surgifoam, Spongistan) has been around since the 1940s. The products have no intrinsic hemostatic action. They absorb 45 times their weight in blood and provide a scaff old on which platelets come into close contact, initiating the release of intrinsic and extrinsic clotting mechanisms.

Oxidized regenerated cellulose

This class (Surgicel, Oxycel) has also been around since the 1940s. The agents have acidic properties, due to their low pH level, and achieve hemostasis via denaturation of blood proteins, mechanical activation of the clotting cascade, and local vasoconstriction.

Because of its low pH, ORC is bactericidal against many common pathogens of the reproductive tract. A few studies have explored laparoscopic application of ORC to achieve hemostasis at sites of uterine perforation and for tubal bleeding secondary to sterilization.1,2 Successful hemostasis of moderate bleeding was achieved without the need for suture or conversion to laparotomy in all cases without brisk arterial bleeding.

Another ORC product (Interceed) is often used in gynecologic surgery as a barrier to adhesion formation. Its degree of oxidation, weave, and pore size differ from those of Surgicel. It requires an absolutely dry operative field to prevent adhesions.

Microfibrillar collagen

Substances derived from bovine collagen were marketed in the 1970s and 1980s. Collagen provides binding sites for platelets, which degranulate, releasing coagulation factors and initiating the clotting cascade.

Microfibrillar collagen products are available in a variety of forms (powder, sheets, loaded syringes for endoscopic placement) and are applied with pressure directly to the bleeding site. Collagen (Instat, Helistat) is supplied as a sponge, whereas microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Superstat, Actifoam, Helitene, Hemopad, Novacol) is a tenacious powder or sheet. Microfibrillar collagen, like porcine gelatin and ORC, is absorbed by the body over time.

No studies have evaluated microfibrillar collagen in gynecologic surgery, although case reports of successful application to sites of uterine perforation after dilation and curettage and to bleeding sites after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy have been published.3,4

New products are largely unproven

Class-III devices require significantly more study before safety and efficacy can be demonstrated. The two types of products presented here—topical thrombin and tissue sealants—remain largely unproven.

Topical thrombin

This class of products has been available for more than 20 years. As a liquid (Thrombogen), topical thrombin can be supplied in a syringe and sprayed onto oozing sites. A liquid combination of collagen gelatin matrix and bovine thrombin (FloSeal) provides a structure on which clots can form; triggers topical conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin; and activates the clotting cascade. It was approved for use in 1999. CoStasis and Vitagel are similar products, approved in 2000 and 2006, respectively, that add plasma obtained from the patient at the beginning of the surgical procedure.

Thrombin and ORC don’t mix. The acidity of ORC inactivates thrombin; therefore, ORC products should not be used with any product containing bovine or human thrombin.

The theoretical advantage of products that use patients’ plasma is the addition of autologous clotting factors and platelets to the bovine collagen and thrombin mixture. Preliminary studies have shown:

- a reduction in postoperative pain in 20 orthopedic surgery patients randomized to platelet gel, compared with what was seen in 20 women in the control group5

- a reduction in the rate of sternal wound infection in cardiac surgery patients (0.3% with the gel; 1.8% without it)6

- a potentially shorter healing time when platelet gel is applied to surgical wounds.7

The facts. Labeling for topical thrombin specifically states that it is not for use in cases of infection or for postpartum hemorrhage or menorrhagia. Studies of topical thrombin products have used the time to cessation of bleeding as their primary effectiveness end-point. In practical terms, however, studies have demonstrated no reduction in the need for transfusion or chest tube drainage in re-operative cardiac surgery patients.8

Disadvantages of topical thrombin include the cost of the product (including the cost of a plasma-collection device) and the need for operating room staff to collect and combine the product for use. Topical thrombin also exposes the patient to the risk of antibody formation (see Bovine thrombin can trigger risky antibodies), catastrophic bleeding, and, even, death.

Products that contain bovine thrombin have some safety issues with regard to their antigenic reactivity. Patients may develop antibodies to the bovine product that cross-react with human thrombin and factor Va. Associated with all products that contain bovine thrombin is a black box warning that states that the product may be associated with severe bleeding, thrombosis, and, rarely, death, because of antibody formation.

In one case report, a very complicated patient who required systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical aortic valve underwent hysterectomy, with topical thrombin administered at the end of the procedure in an effort to avert postoperative hemorrhage.1 She developed antibodies to the bovine thrombin, which caused significant and severe coagulation defects.

No clinical studies have assessed these products in gynecologic surgery.

Reference

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

This last set of products has been approved for use in cardiopulmonary bypass procedures, in patients who have splenic injury, and to close a colostomy. They are “tissue glues” that also have hemostatic properties.

Tisseel is a combination of human thrombin, human “sealer protein” (fibrinogen), and aprotinin, a synthetic inhibitor of fibrinolysis that prevents premature degradation of a clot once it has formed. In clinical studies, this product has reduced the need for splenectomy in patients who have bleeding that is difficult to control.

Disadvantages of tissue-sealing products. These products have not been studied in gynecologic patients. They have the significant disadvantage of containing products derived from pooled human plasma. Although precautions have been taken to reduce transmission of infectious disease, viral transmission may occur. Anaphylaxis is an additional risk.

Many products are available to help the ObGyn surgeon achieve hemostasis in tough situations. Most of the time, we face generalized oozing after treatment of extensive endometriosis or adhesiolysis; in these cases, older topical agents should serve us well. Patients who experience massive bleeding are not likely to benefit from the use of any of the products described in this article.

Extensive bleeding from uterine incisions—at cesarean section or after myomectomy—might respond to topical thrombin, platelet gel products, or tissue sealants, but these products have not been studied in our patients. They also are expensive and carry some risk for our patients.

Don’t overlook two strategies for extremely high-risk situations:

- Cell-saver technology can help avert transfusion in patients expected to lose a substantial amount of blood

- Intravenous recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) can be life-saving for women who experience postpartum hemorrhage, placenta percreta, or retroperitoneal sarcoma and for whom our standard strategies have failed.—BARBARA S. LEVY, MD

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

2. Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:221-222.

3. Borten M, Friedman EA. Translaparoscopic hemostasis with microfibrillar collagen in lieu of laparotomy. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:804-806.

4. Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8:235-238.

5. Zavadil DP, Satterlee CC, Costigan JM, Holt DW, Shostrom VK. Autologous platelet gel and platelet-poor plasma reduce pain with total shoulder arthroplasty. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2007;39:177-182.

6. Trowbridge CC, Stammers AH, Woods E, Yen BR, Klayman M. Use of platelet gel and its effects on infection in cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:381-386.

7. Hom DB, Linzie MB, Huang TC. The healing effects of autologous platelet gel on acute human skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:174-183.

8. Wajon P, Gibson J, Calcroft R, Hughes C, Thrift B. Intraoperative plateletpheresis and autologous platelet gel do not reduce chest tube drainage or allogeneic blood transfusion after reoperative coronary artery bypass graft. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:536-542.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- What clinical problem is this device or drug designed to address?

- Is the problem important clinically for the well-being of my patients?

- What do I know about the basic science and physiology of the problem?

- Are there data supporting improvement in clinical outcomes, or do the studies look only at surrogate endpoints?

- Has the drug or device been studied in gynecologic patients? Is it approved for use in this population?

- Is there evidence that the new technology is more effective, safer, or less expensive than products I use now?

The process of evaluation is critical for us—as advocates for individual patients and as stewards of the diminishing resources available to treat patients in the United States.

With these questions in mind, let’s look at a surgical problem for which there are many new and potentially exciting products being promoted to gynecologic surgeons: the need to achieve hemostasis.

Bleeding is a serious clinical problem during surgery—one that can have a major impact on the well-being of the patient. We generally use sutures and electrosurgical instruments—both bipolar and monopolar—to control major vessels. Topical hemostasis agents may be useful, however, in areas where generalized oozing is present, or where the application of energy may endanger vital structures.

Many products are available for use in these situations. Some are tried and true; others, new or unapproved for use in gynecologic surgery. Your assessment and selection of the optimal product should take into account 1) the cause of bleeding and 2) the mechanism of action of the product.

Surgical bleeding has one of two causes

Although the science of coagulation is complex, bleeding occurs, from a surgical perspective, because of either of two problems:

- failure to control significant arterial and venous sources

- failure of normal clotting functions, such as vasoconstriction; platelet activation and plugging ( FIGURE ); and activation of the coagulation cascade.

No topical or systemic agent adequately controls Problem #1. To address Problem #2, we have several choices to augment hemostasis, including thermal, chemical, and mechanical means. In addition, newer agents deliver additional coagulation-enhancing products such as platelets and thrombin to the operative site to supplement the patient’s natural clotting process.

FIGURE How a clot forms

Tried and true technologies

Because of long-standing experience with porcine gelatin, oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC), and microfibrillar collagen, the Food and Drug Administration recategorized them in 2002 as Class-II devices with a clear safety profile.

Porcine gelatin

This class of products (Gelfoam, Surgifoam, Spongistan) has been around since the 1940s. The products have no intrinsic hemostatic action. They absorb 45 times their weight in blood and provide a scaff old on which platelets come into close contact, initiating the release of intrinsic and extrinsic clotting mechanisms.

Oxidized regenerated cellulose

This class (Surgicel, Oxycel) has also been around since the 1940s. The agents have acidic properties, due to their low pH level, and achieve hemostasis via denaturation of blood proteins, mechanical activation of the clotting cascade, and local vasoconstriction.

Because of its low pH, ORC is bactericidal against many common pathogens of the reproductive tract. A few studies have explored laparoscopic application of ORC to achieve hemostasis at sites of uterine perforation and for tubal bleeding secondary to sterilization.1,2 Successful hemostasis of moderate bleeding was achieved without the need for suture or conversion to laparotomy in all cases without brisk arterial bleeding.

Another ORC product (Interceed) is often used in gynecologic surgery as a barrier to adhesion formation. Its degree of oxidation, weave, and pore size differ from those of Surgicel. It requires an absolutely dry operative field to prevent adhesions.

Microfibrillar collagen

Substances derived from bovine collagen were marketed in the 1970s and 1980s. Collagen provides binding sites for platelets, which degranulate, releasing coagulation factors and initiating the clotting cascade.

Microfibrillar collagen products are available in a variety of forms (powder, sheets, loaded syringes for endoscopic placement) and are applied with pressure directly to the bleeding site. Collagen (Instat, Helistat) is supplied as a sponge, whereas microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Superstat, Actifoam, Helitene, Hemopad, Novacol) is a tenacious powder or sheet. Microfibrillar collagen, like porcine gelatin and ORC, is absorbed by the body over time.

No studies have evaluated microfibrillar collagen in gynecologic surgery, although case reports of successful application to sites of uterine perforation after dilation and curettage and to bleeding sites after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy have been published.3,4

New products are largely unproven

Class-III devices require significantly more study before safety and efficacy can be demonstrated. The two types of products presented here—topical thrombin and tissue sealants—remain largely unproven.

Topical thrombin

This class of products has been available for more than 20 years. As a liquid (Thrombogen), topical thrombin can be supplied in a syringe and sprayed onto oozing sites. A liquid combination of collagen gelatin matrix and bovine thrombin (FloSeal) provides a structure on which clots can form; triggers topical conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin; and activates the clotting cascade. It was approved for use in 1999. CoStasis and Vitagel are similar products, approved in 2000 and 2006, respectively, that add plasma obtained from the patient at the beginning of the surgical procedure.

Thrombin and ORC don’t mix. The acidity of ORC inactivates thrombin; therefore, ORC products should not be used with any product containing bovine or human thrombin.

The theoretical advantage of products that use patients’ plasma is the addition of autologous clotting factors and platelets to the bovine collagen and thrombin mixture. Preliminary studies have shown:

- a reduction in postoperative pain in 20 orthopedic surgery patients randomized to platelet gel, compared with what was seen in 20 women in the control group5

- a reduction in the rate of sternal wound infection in cardiac surgery patients (0.3% with the gel; 1.8% without it)6

- a potentially shorter healing time when platelet gel is applied to surgical wounds.7

The facts. Labeling for topical thrombin specifically states that it is not for use in cases of infection or for postpartum hemorrhage or menorrhagia. Studies of topical thrombin products have used the time to cessation of bleeding as their primary effectiveness end-point. In practical terms, however, studies have demonstrated no reduction in the need for transfusion or chest tube drainage in re-operative cardiac surgery patients.8

Disadvantages of topical thrombin include the cost of the product (including the cost of a plasma-collection device) and the need for operating room staff to collect and combine the product for use. Topical thrombin also exposes the patient to the risk of antibody formation (see Bovine thrombin can trigger risky antibodies), catastrophic bleeding, and, even, death.

Products that contain bovine thrombin have some safety issues with regard to their antigenic reactivity. Patients may develop antibodies to the bovine product that cross-react with human thrombin and factor Va. Associated with all products that contain bovine thrombin is a black box warning that states that the product may be associated with severe bleeding, thrombosis, and, rarely, death, because of antibody formation.

In one case report, a very complicated patient who required systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical aortic valve underwent hysterectomy, with topical thrombin administered at the end of the procedure in an effort to avert postoperative hemorrhage.1 She developed antibodies to the bovine thrombin, which caused significant and severe coagulation defects.

No clinical studies have assessed these products in gynecologic surgery.

Reference

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

This last set of products has been approved for use in cardiopulmonary bypass procedures, in patients who have splenic injury, and to close a colostomy. They are “tissue glues” that also have hemostatic properties.

Tisseel is a combination of human thrombin, human “sealer protein” (fibrinogen), and aprotinin, a synthetic inhibitor of fibrinolysis that prevents premature degradation of a clot once it has formed. In clinical studies, this product has reduced the need for splenectomy in patients who have bleeding that is difficult to control.

Disadvantages of tissue-sealing products. These products have not been studied in gynecologic patients. They have the significant disadvantage of containing products derived from pooled human plasma. Although precautions have been taken to reduce transmission of infectious disease, viral transmission may occur. Anaphylaxis is an additional risk.

Many products are available to help the ObGyn surgeon achieve hemostasis in tough situations. Most of the time, we face generalized oozing after treatment of extensive endometriosis or adhesiolysis; in these cases, older topical agents should serve us well. Patients who experience massive bleeding are not likely to benefit from the use of any of the products described in this article.

Extensive bleeding from uterine incisions—at cesarean section or after myomectomy—might respond to topical thrombin, platelet gel products, or tissue sealants, but these products have not been studied in our patients. They also are expensive and carry some risk for our patients.

Don’t overlook two strategies for extremely high-risk situations:

- Cell-saver technology can help avert transfusion in patients expected to lose a substantial amount of blood

- Intravenous recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) can be life-saving for women who experience postpartum hemorrhage, placenta percreta, or retroperitoneal sarcoma and for whom our standard strategies have failed.—BARBARA S. LEVY, MD

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

- What clinical problem is this device or drug designed to address?

- Is the problem important clinically for the well-being of my patients?

- What do I know about the basic science and physiology of the problem?

- Are there data supporting improvement in clinical outcomes, or do the studies look only at surrogate endpoints?

- Has the drug or device been studied in gynecologic patients? Is it approved for use in this population?

- Is there evidence that the new technology is more effective, safer, or less expensive than products I use now?

The process of evaluation is critical for us—as advocates for individual patients and as stewards of the diminishing resources available to treat patients in the United States.

With these questions in mind, let’s look at a surgical problem for which there are many new and potentially exciting products being promoted to gynecologic surgeons: the need to achieve hemostasis.

Bleeding is a serious clinical problem during surgery—one that can have a major impact on the well-being of the patient. We generally use sutures and electrosurgical instruments—both bipolar and monopolar—to control major vessels. Topical hemostasis agents may be useful, however, in areas where generalized oozing is present, or where the application of energy may endanger vital structures.

Many products are available for use in these situations. Some are tried and true; others, new or unapproved for use in gynecologic surgery. Your assessment and selection of the optimal product should take into account 1) the cause of bleeding and 2) the mechanism of action of the product.

Surgical bleeding has one of two causes

Although the science of coagulation is complex, bleeding occurs, from a surgical perspective, because of either of two problems:

- failure to control significant arterial and venous sources

- failure of normal clotting functions, such as vasoconstriction; platelet activation and plugging ( FIGURE ); and activation of the coagulation cascade.

No topical or systemic agent adequately controls Problem #1. To address Problem #2, we have several choices to augment hemostasis, including thermal, chemical, and mechanical means. In addition, newer agents deliver additional coagulation-enhancing products such as platelets and thrombin to the operative site to supplement the patient’s natural clotting process.

FIGURE How a clot forms

Tried and true technologies

Because of long-standing experience with porcine gelatin, oxidized regenerated cellulose (ORC), and microfibrillar collagen, the Food and Drug Administration recategorized them in 2002 as Class-II devices with a clear safety profile.

Porcine gelatin

This class of products (Gelfoam, Surgifoam, Spongistan) has been around since the 1940s. The products have no intrinsic hemostatic action. They absorb 45 times their weight in blood and provide a scaff old on which platelets come into close contact, initiating the release of intrinsic and extrinsic clotting mechanisms.

Oxidized regenerated cellulose

This class (Surgicel, Oxycel) has also been around since the 1940s. The agents have acidic properties, due to their low pH level, and achieve hemostasis via denaturation of blood proteins, mechanical activation of the clotting cascade, and local vasoconstriction.

Because of its low pH, ORC is bactericidal against many common pathogens of the reproductive tract. A few studies have explored laparoscopic application of ORC to achieve hemostasis at sites of uterine perforation and for tubal bleeding secondary to sterilization.1,2 Successful hemostasis of moderate bleeding was achieved without the need for suture or conversion to laparotomy in all cases without brisk arterial bleeding.

Another ORC product (Interceed) is often used in gynecologic surgery as a barrier to adhesion formation. Its degree of oxidation, weave, and pore size differ from those of Surgicel. It requires an absolutely dry operative field to prevent adhesions.

Microfibrillar collagen

Substances derived from bovine collagen were marketed in the 1970s and 1980s. Collagen provides binding sites for platelets, which degranulate, releasing coagulation factors and initiating the clotting cascade.

Microfibrillar collagen products are available in a variety of forms (powder, sheets, loaded syringes for endoscopic placement) and are applied with pressure directly to the bleeding site. Collagen (Instat, Helistat) is supplied as a sponge, whereas microfibrillar collagen (Avitene, Superstat, Actifoam, Helitene, Hemopad, Novacol) is a tenacious powder or sheet. Microfibrillar collagen, like porcine gelatin and ORC, is absorbed by the body over time.

No studies have evaluated microfibrillar collagen in gynecologic surgery, although case reports of successful application to sites of uterine perforation after dilation and curettage and to bleeding sites after vaginal or laparoscopic hysterectomy have been published.3,4

New products are largely unproven

Class-III devices require significantly more study before safety and efficacy can be demonstrated. The two types of products presented here—topical thrombin and tissue sealants—remain largely unproven.

Topical thrombin

This class of products has been available for more than 20 years. As a liquid (Thrombogen), topical thrombin can be supplied in a syringe and sprayed onto oozing sites. A liquid combination of collagen gelatin matrix and bovine thrombin (FloSeal) provides a structure on which clots can form; triggers topical conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin; and activates the clotting cascade. It was approved for use in 1999. CoStasis and Vitagel are similar products, approved in 2000 and 2006, respectively, that add plasma obtained from the patient at the beginning of the surgical procedure.

Thrombin and ORC don’t mix. The acidity of ORC inactivates thrombin; therefore, ORC products should not be used with any product containing bovine or human thrombin.

The theoretical advantage of products that use patients’ plasma is the addition of autologous clotting factors and platelets to the bovine collagen and thrombin mixture. Preliminary studies have shown:

- a reduction in postoperative pain in 20 orthopedic surgery patients randomized to platelet gel, compared with what was seen in 20 women in the control group5

- a reduction in the rate of sternal wound infection in cardiac surgery patients (0.3% with the gel; 1.8% without it)6

- a potentially shorter healing time when platelet gel is applied to surgical wounds.7

The facts. Labeling for topical thrombin specifically states that it is not for use in cases of infection or for postpartum hemorrhage or menorrhagia. Studies of topical thrombin products have used the time to cessation of bleeding as their primary effectiveness end-point. In practical terms, however, studies have demonstrated no reduction in the need for transfusion or chest tube drainage in re-operative cardiac surgery patients.8

Disadvantages of topical thrombin include the cost of the product (including the cost of a plasma-collection device) and the need for operating room staff to collect and combine the product for use. Topical thrombin also exposes the patient to the risk of antibody formation (see Bovine thrombin can trigger risky antibodies), catastrophic bleeding, and, even, death.

Products that contain bovine thrombin have some safety issues with regard to their antigenic reactivity. Patients may develop antibodies to the bovine product that cross-react with human thrombin and factor Va. Associated with all products that contain bovine thrombin is a black box warning that states that the product may be associated with severe bleeding, thrombosis, and, rarely, death, because of antibody formation.

In one case report, a very complicated patient who required systemic anticoagulation for a mechanical aortic valve underwent hysterectomy, with topical thrombin administered at the end of the procedure in an effort to avert postoperative hemorrhage.1 She developed antibodies to the bovine thrombin, which caused significant and severe coagulation defects.

No clinical studies have assessed these products in gynecologic surgery.

Reference

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

This last set of products has been approved for use in cardiopulmonary bypass procedures, in patients who have splenic injury, and to close a colostomy. They are “tissue glues” that also have hemostatic properties.

Tisseel is a combination of human thrombin, human “sealer protein” (fibrinogen), and aprotinin, a synthetic inhibitor of fibrinolysis that prevents premature degradation of a clot once it has formed. In clinical studies, this product has reduced the need for splenectomy in patients who have bleeding that is difficult to control.

Disadvantages of tissue-sealing products. These products have not been studied in gynecologic patients. They have the significant disadvantage of containing products derived from pooled human plasma. Although precautions have been taken to reduce transmission of infectious disease, viral transmission may occur. Anaphylaxis is an additional risk.

Many products are available to help the ObGyn surgeon achieve hemostasis in tough situations. Most of the time, we face generalized oozing after treatment of extensive endometriosis or adhesiolysis; in these cases, older topical agents should serve us well. Patients who experience massive bleeding are not likely to benefit from the use of any of the products described in this article.

Extensive bleeding from uterine incisions—at cesarean section or after myomectomy—might respond to topical thrombin, platelet gel products, or tissue sealants, but these products have not been studied in our patients. They also are expensive and carry some risk for our patients.

Don’t overlook two strategies for extremely high-risk situations:

- Cell-saver technology can help avert transfusion in patients expected to lose a substantial amount of blood

- Intravenous recombinant activated factor VII (NovoSeven) can be life-saving for women who experience postpartum hemorrhage, placenta percreta, or retroperitoneal sarcoma and for whom our standard strategies have failed.—BARBARA S. LEVY, MD

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

2. Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:221-222.

3. Borten M, Friedman EA. Translaparoscopic hemostasis with microfibrillar collagen in lieu of laparotomy. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:804-806.

4. Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8:235-238.

5. Zavadil DP, Satterlee CC, Costigan JM, Holt DW, Shostrom VK. Autologous platelet gel and platelet-poor plasma reduce pain with total shoulder arthroplasty. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2007;39:177-182.

6. Trowbridge CC, Stammers AH, Woods E, Yen BR, Klayman M. Use of platelet gel and its effects on infection in cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:381-386.

7. Hom DB, Linzie MB, Huang TC. The healing effects of autologous platelet gel on acute human skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:174-183.

8. Wajon P, Gibson J, Calcroft R, Hughes C, Thrift B. Intraoperative plateletpheresis and autologous platelet gel do not reduce chest tube drainage or allogeneic blood transfusion after reoperative coronary artery bypass graft. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:536-542.

1. Sharma JB, Malhotra M, Pundir P. Laparoscopic oxidized cellulose (Surgicel) application for small uterine perforations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83:271-275.

2. Sharma JB, Malhotra M. Topical oxidized cellulose for tubal hemorrhage hemostasis during laparoscopic sterilization. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:221-222.

3. Borten M, Friedman EA. Translaparoscopic hemostasis with microfibrillar collagen in lieu of laparotomy. A report of two cases. J Reprod Med. 1983;28:804-806.

4. Holub Z, Jabor A. Laparoscopic management of bleeding after laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy. JSLS. 2004;8:235-238.

5. Zavadil DP, Satterlee CC, Costigan JM, Holt DW, Shostrom VK. Autologous platelet gel and platelet-poor plasma reduce pain with total shoulder arthroplasty. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2007;39:177-182.

6. Trowbridge CC, Stammers AH, Woods E, Yen BR, Klayman M. Use of platelet gel and its effects on infection in cardiac surgery. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2005;37:381-386.

7. Hom DB, Linzie MB, Huang TC. The healing effects of autologous platelet gel on acute human skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:174-183.

8. Wajon P, Gibson J, Calcroft R, Hughes C, Thrift B. Intraoperative plateletpheresis and autologous platelet gel do not reduce chest tube drainage or allogeneic blood transfusion after reoperative coronary artery bypass graft. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:536-542.

The minimally invasive 21st Century, at your fingertips

Sunday morning, and I am sitting at the computer writing this “Editorial” and trying to juggle my tasks for the conclusion of the year—tasks that include over 25,000 miles’ worth of travel to meetings and other events! One of those trips will take me across the country to the “other Washington” for AAGL’s 36th Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, November 13 to 17. Although I’m obliged, as presenter and past-president of AAGL, to travel to the congress, I’m pleased to tell you that an exciting collaboration between AAGL and OBG Management will make it possible for you to access key congress events—scientific presentations, industry symposia, expert debates, live telesurgery, surgical tutorials, and even the exhibit hall—from home or office!

The “full flavor” of the congress

Attending the AAGL Congress has always been an adventure for me. What I learn there challenges my thinking about minimally invasive surgical management and pushes me to evaluate new approaches to optimal care. Through the AAGL-OBG Management collaboration, much of that intellectual challenge will be available to surgeons whenever they can get to a computer.

Entering the congress highlights via www.aagl.org, www.aaglcongress.com, or www.obgmanagement.com, you will find an environment where some of the latest tools and tricks displayed at the congress can be viewed. There will be audio and video news coverage of key events from the meeting floor, podcasts, webcasts, and the text of talks with PowerPoint presentations. This trove will give you the full flavor of the meeting.

Keep in mind that I don’t mean “press” coverage or interpretation of activities; rather, these are presentations that have been vetted by AAGL’s scientific program and CME committees. The material will be referenced and organized so that you can focus your attention on subjects of everyday interest and utility.

One plus one is…three, or greater

Both AAGL and OBG Management have been leaders in promoting innovation in gynecologic surgery and providing ObGyns with evidence-based, peer-reviewed scientific papers to help inform our clinical practices. Their collaboration is truly cutting edge: It combines the expertise and integrity of AAGL in teaching minimally invasive gynecology with OBG Management’s technology and expertise in information handling and presentation. The outcome? We’ll be able to learn, more efficiently and more effectively, the most innovative treatments.

To those of you who will attend AAGL’s Global Congress—I look forward to seeing you. To those who cannot be there—welcome to the technology that makes a virtual meeting possible!

Sunday morning, and I am sitting at the computer writing this “Editorial” and trying to juggle my tasks for the conclusion of the year—tasks that include over 25,000 miles’ worth of travel to meetings and other events! One of those trips will take me across the country to the “other Washington” for AAGL’s 36th Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, November 13 to 17. Although I’m obliged, as presenter and past-president of AAGL, to travel to the congress, I’m pleased to tell you that an exciting collaboration between AAGL and OBG Management will make it possible for you to access key congress events—scientific presentations, industry symposia, expert debates, live telesurgery, surgical tutorials, and even the exhibit hall—from home or office!

The “full flavor” of the congress

Attending the AAGL Congress has always been an adventure for me. What I learn there challenges my thinking about minimally invasive surgical management and pushes me to evaluate new approaches to optimal care. Through the AAGL-OBG Management collaboration, much of that intellectual challenge will be available to surgeons whenever they can get to a computer.

Entering the congress highlights via www.aagl.org, www.aaglcongress.com, or www.obgmanagement.com, you will find an environment where some of the latest tools and tricks displayed at the congress can be viewed. There will be audio and video news coverage of key events from the meeting floor, podcasts, webcasts, and the text of talks with PowerPoint presentations. This trove will give you the full flavor of the meeting.

Keep in mind that I don’t mean “press” coverage or interpretation of activities; rather, these are presentations that have been vetted by AAGL’s scientific program and CME committees. The material will be referenced and organized so that you can focus your attention on subjects of everyday interest and utility.

One plus one is…three, or greater

Both AAGL and OBG Management have been leaders in promoting innovation in gynecologic surgery and providing ObGyns with evidence-based, peer-reviewed scientific papers to help inform our clinical practices. Their collaboration is truly cutting edge: It combines the expertise and integrity of AAGL in teaching minimally invasive gynecology with OBG Management’s technology and expertise in information handling and presentation. The outcome? We’ll be able to learn, more efficiently and more effectively, the most innovative treatments.

To those of you who will attend AAGL’s Global Congress—I look forward to seeing you. To those who cannot be there—welcome to the technology that makes a virtual meeting possible!

Sunday morning, and I am sitting at the computer writing this “Editorial” and trying to juggle my tasks for the conclusion of the year—tasks that include over 25,000 miles’ worth of travel to meetings and other events! One of those trips will take me across the country to the “other Washington” for AAGL’s 36th Global Congress of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, November 13 to 17. Although I’m obliged, as presenter and past-president of AAGL, to travel to the congress, I’m pleased to tell you that an exciting collaboration between AAGL and OBG Management will make it possible for you to access key congress events—scientific presentations, industry symposia, expert debates, live telesurgery, surgical tutorials, and even the exhibit hall—from home or office!

The “full flavor” of the congress

Attending the AAGL Congress has always been an adventure for me. What I learn there challenges my thinking about minimally invasive surgical management and pushes me to evaluate new approaches to optimal care. Through the AAGL-OBG Management collaboration, much of that intellectual challenge will be available to surgeons whenever they can get to a computer.

Entering the congress highlights via www.aagl.org, www.aaglcongress.com, or www.obgmanagement.com, you will find an environment where some of the latest tools and tricks displayed at the congress can be viewed. There will be audio and video news coverage of key events from the meeting floor, podcasts, webcasts, and the text of talks with PowerPoint presentations. This trove will give you the full flavor of the meeting.

Keep in mind that I don’t mean “press” coverage or interpretation of activities; rather, these are presentations that have been vetted by AAGL’s scientific program and CME committees. The material will be referenced and organized so that you can focus your attention on subjects of everyday interest and utility.

One plus one is…three, or greater

Both AAGL and OBG Management have been leaders in promoting innovation in gynecologic surgery and providing ObGyns with evidence-based, peer-reviewed scientific papers to help inform our clinical practices. Their collaboration is truly cutting edge: It combines the expertise and integrity of AAGL in teaching minimally invasive gynecology with OBG Management’s technology and expertise in information handling and presentation. The outcome? We’ll be able to learn, more efficiently and more effectively, the most innovative treatments.

To those of you who will attend AAGL’s Global Congress—I look forward to seeing you. To those who cannot be there—welcome to the technology that makes a virtual meeting possible!

TECHNOLOGY

Over its history, surgery has been defined by the tools available to practitioners. In our era, opportunities to offer patients minimally invasive surgery have expanded dramatically as methods of establishing visualization, achieving hemostasis, and performing tissue dissection have improved. (I remember trying to treat ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically in the early 1980s without benefit of a camera or suction irrigator!)

For surgeons of my generation, the ability to access the abdominal cavity minimally invasively and to clearly visualize the contents was a significant step forward. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was another tremendous incremental improvement for patients with submucous myomas. But there is much more in store for the coming years.

Where are we headed in the next wave of gynecologic surgery? Will patients require an incision at all? Is there room to advance beyond laparoscopy and hysteroscopy? What innovations will industry offer us in the 21st century?

In this article, I describe something that is fairly familiar to most of us by now, but which is not yet practical for routine gynecologic procedures—robotically assisted endoscopic surgery. I then move on to a phenomenon that, in many respects, is still being imagined—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES.

Robotic systems are best suited for complex surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is limited by the two-dimensional view and need for hand control of long, rigid instruments through ancillary trocar sites. Although these impediments can be overcome with practice and experience, the inability to see in three dimensions and the compromised range of motion hamper optimal management of some surgical procedures.

A number of technological advances may significantly improve our ability to perform suture-intensive or anatomically challenging operations. Several companies are developing camera systems that will permit a three-dimensional view without the need for multiple visual ports. The technology is borrowed from the world of insects, which “see” through multiple lenses within the same eye. The application of such visual processing to optical systems for endoscopic surgery will be a huge advance for laparoscopy—one that is still being perfected by industry. In 2007, the da Vinci robot system (Intuitive Surgical) offers the best opportunity to achieve both three-dimensional visualization and an ability to “feel” tissue and manipulate instruments with markedly increased range of motion.

Cost is the limiting factor

Although the da Vinci system has revolutionized the practice of urology, enabling radical nerve-sparing prostatectomy, its utility in gynecology is still being investigated. Several centers use the robot for a significant percentage of their laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, but the setup time, learning curve, and intraoperative time required make the da Vinci system an impractical tool for many routine procedures. Its true advantage lies in suture-intensive procedures and in surgeries that require meticulous dissection close to major structures. In gynecology, the laparoscopic procedures most likely to benefit from the three-dimensional view and articulating instruments are sacral colpopexy, myomectomy (FIGURE), radical hysterectomy, and lymph node dissection.

Although it is interesting and enjoyable to use robotic technology for routine laparoscopic procedures, I believe the cost is prohibitive—several million dollars for each robot. If the financial barriers are removed, however, this system will be a welcome addition to the toolset for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Until then, we need to make intelligent use of this powerful tool.

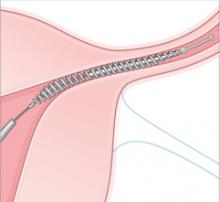

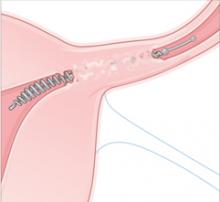

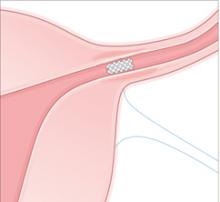

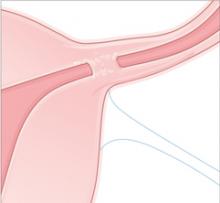

FIGURE Robotic myomectomy

A: Using the da Vinci robot, the surgeon incises the myometrium down to the fibroid.

B: After grasping the fibroid, the surgeon dissects it away from the surrounding myometrium.

C: As the fibroid is freed, another small tumor becomes apparent at the bottom right, and is also removed.

D: The myometrium is sutured in layers after removal of the fibroids. Photos courtesy of Paul Indman, MD.Just as many of us were able to perform laparoscopic surgery without a three-chip camera and high-tech energy system for hemostasis until the cost of those technologies could be recouped in reduced operating room time and fewer conversions to laparotomy, so will today’s surgeons have to continue performing laparoscopic adnexal surgery, routine hysterectomy, and treatment of ectopic pregnancy the “old-fashioned” way. For complex procedures, however, the da Vinci system is proving to be a major advance in endoscopic surgery.

Look for other, perhaps less expensive, technologies coming down the road that will, at the very least, permit three-dimensional visualization without the need for robotics. In addition, as I discuss in the next section, miniaturization of robotics is on the horizon. Only our imagination limits our thinking about how robotic technology may be used in the not-too-distant future.

ROBOTICS IN GYNECOLOGY

Selected studies

- Bocca S, Stadtmauer L, Oehninger S. Uncomplicated fullterm pregnancy after da Vinci-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:246–249.

- Elliott DS, Chow GK, Gettman M. Current status of robotics in female urology and gynecology. World J Urol. 2006;24:188–192.

- Fiorentino RP, Zepeda MA, Goldstein BH, John CR, Rettenmaier MA. Pilot study assessing robotic laparoscopic hysterectomy and patient outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:60–63.

- Magrina JF. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:77–82.

NOTES takes “minimally invasive” to a new level

Imagine performing surgery for ectopic pregnancy or endometriosis in your office, without anesthesia. Think this is impossible? Think again!

A newer, perhaps better, and definitely less invasive version of endoscopic surgery is on the horizon—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES. In May, a surgeon in Portland, Oregon, performed a cholecystectomy by dropping an endoscope through the patient’s mouth into the stomach, drilling an opening in the gastric wall, and placing small instruments through that opening to perform the surgery. The specimen was then pulled through the small opening in the stomach and retrieved through the patient’s mouth! The stomach was closed with an endoscopic stapling device.

NOTES appears to be the next true advance in minimally invasive surgery. This should come as no surprise to gynecologists. We are the champions of transcervical and transvaginal surgery. General surgeons and gastroenterologists are recognizing what we have long known—that operating through these natural orifices is less uncomfortable for the patient and provides faster, less complicated recovery. They are also recognizing the challenges involved in such an approach.

A new generation of instruments is in the works

Clearly, operating through the vagina, cervix, or stomach necessitates excellent visualization and instruments flexible enough to navigate through tiny openings but strong enough to transect and retrieve tissue. Many of our industry partners are working diligently to create and perfect new instrumentation for NOTES procedures, and research is under way at many centers in this country and overseas into transgastric and transrectal procedures.

Consider what we might be able to achieve with this technology! By eliminating the need for transabdominal access, we can vastly reduce the risk of intestinal and major vessel injury and eliminate the risk of hernia. We can also markedly reduce the discomfort associated with abdominal incisions.

How might this technology be applied in gynecology? I anticipate that ovarian pathology, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy will be managed transvaginally or via a small opening in the uterus. Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy—in which warm saline is used as the distention medium instead of carbon dioxide, and access to the pelvis is achieved through a small culpotomy—has been around for many years but is limited by the rigid instrumentation and restricted visualization now available. With flexible instruments that can “see” around corners yet provide a wide visual field, microrobots that can be placed through a tiny opening and then deployed to accomplish the surgical task, and systems to achieve hemostasis, NOTES may be the next revolution in gynecologic surgery.

Still in a very early stage of development, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has generated considerable enthusiasm among physicians leading research and development efforts. Hoping to steer these efforts in a responsible direction—and avoid the problems encountered during the early days of laparoscopic surgery, when many inexperienced practitioners began adopting the technique prematurely—a working group from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons was formed in 2005, calling itself the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortium for Assessment and Research (NOSCAR). So far, this group has convened two international conferences and penned two white papers, noting that “the overwhelming sense [at the first international conference]…was that NOTES will develop into a mainstream clinical capability in the near future.”1

Some of the needs NOSCAR has identified are:

- determining the optimal technique and site to achieve access to the peritoneal cavity

- developing a gastric closure method that is 100% reliable

- reducing the risk of intraperitoneal contamination and infection, given the transgastric route that has dominated NOTES so far

- developing the ability to suture

- maintaining spatial orientation during surgery, as well as a multitasking platform that would allow manipulation of tissue, clear visualization, and safe access

- preventing intraperitoneal complications such as bleeding and bowel perforation

- exploring the physiology of pneumoperitoneum in the setting of NOTES

- establishing guidelines for training physicians and reporting both positive and negative outcomes.

In the meantime, NOSCAR recommends that all NOTES procedures in humans be approved by the Institutional Review Board and reported to a registry.

So far, the technology has been used to perform appendectomy and cholecystectomy in humans. Research grants totaling $1.5 million have been pledged by industry.

Reference

1. NOSCAR Working Group. NOTES: gathering momentum. White Paper. May 2006. Available at: http://www.noscar.org/documents/NOTES_White_Paper_May06.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2007.

NATURAL ORIFICE TRANSLUMINAL ENDOSCOPIC SURGERY (NOTES)

Selected studies

To date, 19 abstracts on PubMed discuss the impressive opportunities NOTES will provide. Here is a sample:

- de la Fuente SG, Demaria EJ, Reynolds JD, Portenier DD, Pryor AD. New developments in surgery: natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Arch Surg. 2007;142:295–297.

- Fong DG, Pai RD, Thompson CC. Transcolonic endoscopic abdominal exploration: a NOTES survival study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:312–318.

- Malik A, Mellinger JD, Hazey JW, Dunkin BJ, MacFadyen BV. Endoluminal and transluminal surgery: current status and future possibilities. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1179–1192.

- McGee MF, Rosen MJ, Marks J, et al. A primer on natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery: building a new paradigm. Surg Innov. 2006;13:86–93.

- Wilhelm D, Meining A, von Delius S, et al. An innovative, safe and sterile sigmoid access (ISSA) for NOTES. Endoscopy. 2007;39:401–406.

Over its history, surgery has been defined by the tools available to practitioners. In our era, opportunities to offer patients minimally invasive surgery have expanded dramatically as methods of establishing visualization, achieving hemostasis, and performing tissue dissection have improved. (I remember trying to treat ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically in the early 1980s without benefit of a camera or suction irrigator!)

For surgeons of my generation, the ability to access the abdominal cavity minimally invasively and to clearly visualize the contents was a significant step forward. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was another tremendous incremental improvement for patients with submucous myomas. But there is much more in store for the coming years.

Where are we headed in the next wave of gynecologic surgery? Will patients require an incision at all? Is there room to advance beyond laparoscopy and hysteroscopy? What innovations will industry offer us in the 21st century?

In this article, I describe something that is fairly familiar to most of us by now, but which is not yet practical for routine gynecologic procedures—robotically assisted endoscopic surgery. I then move on to a phenomenon that, in many respects, is still being imagined—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES.

Robotic systems are best suited for complex surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is limited by the two-dimensional view and need for hand control of long, rigid instruments through ancillary trocar sites. Although these impediments can be overcome with practice and experience, the inability to see in three dimensions and the compromised range of motion hamper optimal management of some surgical procedures.

A number of technological advances may significantly improve our ability to perform suture-intensive or anatomically challenging operations. Several companies are developing camera systems that will permit a three-dimensional view without the need for multiple visual ports. The technology is borrowed from the world of insects, which “see” through multiple lenses within the same eye. The application of such visual processing to optical systems for endoscopic surgery will be a huge advance for laparoscopy—one that is still being perfected by industry. In 2007, the da Vinci robot system (Intuitive Surgical) offers the best opportunity to achieve both three-dimensional visualization and an ability to “feel” tissue and manipulate instruments with markedly increased range of motion.

Cost is the limiting factor

Although the da Vinci system has revolutionized the practice of urology, enabling radical nerve-sparing prostatectomy, its utility in gynecology is still being investigated. Several centers use the robot for a significant percentage of their laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, but the setup time, learning curve, and intraoperative time required make the da Vinci system an impractical tool for many routine procedures. Its true advantage lies in suture-intensive procedures and in surgeries that require meticulous dissection close to major structures. In gynecology, the laparoscopic procedures most likely to benefit from the three-dimensional view and articulating instruments are sacral colpopexy, myomectomy (FIGURE), radical hysterectomy, and lymph node dissection.

Although it is interesting and enjoyable to use robotic technology for routine laparoscopic procedures, I believe the cost is prohibitive—several million dollars for each robot. If the financial barriers are removed, however, this system will be a welcome addition to the toolset for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Until then, we need to make intelligent use of this powerful tool.

FIGURE Robotic myomectomy

A: Using the da Vinci robot, the surgeon incises the myometrium down to the fibroid.

B: After grasping the fibroid, the surgeon dissects it away from the surrounding myometrium.

C: As the fibroid is freed, another small tumor becomes apparent at the bottom right, and is also removed.

D: The myometrium is sutured in layers after removal of the fibroids. Photos courtesy of Paul Indman, MD.Just as many of us were able to perform laparoscopic surgery without a three-chip camera and high-tech energy system for hemostasis until the cost of those technologies could be recouped in reduced operating room time and fewer conversions to laparotomy, so will today’s surgeons have to continue performing laparoscopic adnexal surgery, routine hysterectomy, and treatment of ectopic pregnancy the “old-fashioned” way. For complex procedures, however, the da Vinci system is proving to be a major advance in endoscopic surgery.

Look for other, perhaps less expensive, technologies coming down the road that will, at the very least, permit three-dimensional visualization without the need for robotics. In addition, as I discuss in the next section, miniaturization of robotics is on the horizon. Only our imagination limits our thinking about how robotic technology may be used in the not-too-distant future.

ROBOTICS IN GYNECOLOGY

Selected studies

- Bocca S, Stadtmauer L, Oehninger S. Uncomplicated fullterm pregnancy after da Vinci-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:246–249.

- Elliott DS, Chow GK, Gettman M. Current status of robotics in female urology and gynecology. World J Urol. 2006;24:188–192.

- Fiorentino RP, Zepeda MA, Goldstein BH, John CR, Rettenmaier MA. Pilot study assessing robotic laparoscopic hysterectomy and patient outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:60–63.

- Magrina JF. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:77–82.

NOTES takes “minimally invasive” to a new level

Imagine performing surgery for ectopic pregnancy or endometriosis in your office, without anesthesia. Think this is impossible? Think again!

A newer, perhaps better, and definitely less invasive version of endoscopic surgery is on the horizon—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES. In May, a surgeon in Portland, Oregon, performed a cholecystectomy by dropping an endoscope through the patient’s mouth into the stomach, drilling an opening in the gastric wall, and placing small instruments through that opening to perform the surgery. The specimen was then pulled through the small opening in the stomach and retrieved through the patient’s mouth! The stomach was closed with an endoscopic stapling device.

NOTES appears to be the next true advance in minimally invasive surgery. This should come as no surprise to gynecologists. We are the champions of transcervical and transvaginal surgery. General surgeons and gastroenterologists are recognizing what we have long known—that operating through these natural orifices is less uncomfortable for the patient and provides faster, less complicated recovery. They are also recognizing the challenges involved in such an approach.

A new generation of instruments is in the works

Clearly, operating through the vagina, cervix, or stomach necessitates excellent visualization and instruments flexible enough to navigate through tiny openings but strong enough to transect and retrieve tissue. Many of our industry partners are working diligently to create and perfect new instrumentation for NOTES procedures, and research is under way at many centers in this country and overseas into transgastric and transrectal procedures.

Consider what we might be able to achieve with this technology! By eliminating the need for transabdominal access, we can vastly reduce the risk of intestinal and major vessel injury and eliminate the risk of hernia. We can also markedly reduce the discomfort associated with abdominal incisions.

How might this technology be applied in gynecology? I anticipate that ovarian pathology, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy will be managed transvaginally or via a small opening in the uterus. Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy—in which warm saline is used as the distention medium instead of carbon dioxide, and access to the pelvis is achieved through a small culpotomy—has been around for many years but is limited by the rigid instrumentation and restricted visualization now available. With flexible instruments that can “see” around corners yet provide a wide visual field, microrobots that can be placed through a tiny opening and then deployed to accomplish the surgical task, and systems to achieve hemostasis, NOTES may be the next revolution in gynecologic surgery.

Still in a very early stage of development, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has generated considerable enthusiasm among physicians leading research and development efforts. Hoping to steer these efforts in a responsible direction—and avoid the problems encountered during the early days of laparoscopic surgery, when many inexperienced practitioners began adopting the technique prematurely—a working group from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons was formed in 2005, calling itself the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortium for Assessment and Research (NOSCAR). So far, this group has convened two international conferences and penned two white papers, noting that “the overwhelming sense [at the first international conference]…was that NOTES will develop into a mainstream clinical capability in the near future.”1

Some of the needs NOSCAR has identified are:

- determining the optimal technique and site to achieve access to the peritoneal cavity

- developing a gastric closure method that is 100% reliable

- reducing the risk of intraperitoneal contamination and infection, given the transgastric route that has dominated NOTES so far

- developing the ability to suture

- maintaining spatial orientation during surgery, as well as a multitasking platform that would allow manipulation of tissue, clear visualization, and safe access

- preventing intraperitoneal complications such as bleeding and bowel perforation

- exploring the physiology of pneumoperitoneum in the setting of NOTES

- establishing guidelines for training physicians and reporting both positive and negative outcomes.

In the meantime, NOSCAR recommends that all NOTES procedures in humans be approved by the Institutional Review Board and reported to a registry.

So far, the technology has been used to perform appendectomy and cholecystectomy in humans. Research grants totaling $1.5 million have been pledged by industry.

Reference

1. NOSCAR Working Group. NOTES: gathering momentum. White Paper. May 2006. Available at: http://www.noscar.org/documents/NOTES_White_Paper_May06.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2007.

NATURAL ORIFICE TRANSLUMINAL ENDOSCOPIC SURGERY (NOTES)

Selected studies

To date, 19 abstracts on PubMed discuss the impressive opportunities NOTES will provide. Here is a sample:

- de la Fuente SG, Demaria EJ, Reynolds JD, Portenier DD, Pryor AD. New developments in surgery: natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Arch Surg. 2007;142:295–297.

- Fong DG, Pai RD, Thompson CC. Transcolonic endoscopic abdominal exploration: a NOTES survival study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:312–318.

- Malik A, Mellinger JD, Hazey JW, Dunkin BJ, MacFadyen BV. Endoluminal and transluminal surgery: current status and future possibilities. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1179–1192.

- McGee MF, Rosen MJ, Marks J, et al. A primer on natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery: building a new paradigm. Surg Innov. 2006;13:86–93.

- Wilhelm D, Meining A, von Delius S, et al. An innovative, safe and sterile sigmoid access (ISSA) for NOTES. Endoscopy. 2007;39:401–406.

Over its history, surgery has been defined by the tools available to practitioners. In our era, opportunities to offer patients minimally invasive surgery have expanded dramatically as methods of establishing visualization, achieving hemostasis, and performing tissue dissection have improved. (I remember trying to treat ectopic pregnancy laparoscopically in the early 1980s without benefit of a camera or suction irrigator!)

For surgeons of my generation, the ability to access the abdominal cavity minimally invasively and to clearly visualize the contents was a significant step forward. Hysteroscopic myomectomy was another tremendous incremental improvement for patients with submucous myomas. But there is much more in store for the coming years.

Where are we headed in the next wave of gynecologic surgery? Will patients require an incision at all? Is there room to advance beyond laparoscopy and hysteroscopy? What innovations will industry offer us in the 21st century?

In this article, I describe something that is fairly familiar to most of us by now, but which is not yet practical for routine gynecologic procedures—robotically assisted endoscopic surgery. I then move on to a phenomenon that, in many respects, is still being imagined—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES.

Robotic systems are best suited for complex surgery

Laparoscopic surgery is limited by the two-dimensional view and need for hand control of long, rigid instruments through ancillary trocar sites. Although these impediments can be overcome with practice and experience, the inability to see in three dimensions and the compromised range of motion hamper optimal management of some surgical procedures.

A number of technological advances may significantly improve our ability to perform suture-intensive or anatomically challenging operations. Several companies are developing camera systems that will permit a three-dimensional view without the need for multiple visual ports. The technology is borrowed from the world of insects, which “see” through multiple lenses within the same eye. The application of such visual processing to optical systems for endoscopic surgery will be a huge advance for laparoscopy—one that is still being perfected by industry. In 2007, the da Vinci robot system (Intuitive Surgical) offers the best opportunity to achieve both three-dimensional visualization and an ability to “feel” tissue and manipulate instruments with markedly increased range of motion.

Cost is the limiting factor

Although the da Vinci system has revolutionized the practice of urology, enabling radical nerve-sparing prostatectomy, its utility in gynecology is still being investigated. Several centers use the robot for a significant percentage of their laparoscopic gynecologic surgery, but the setup time, learning curve, and intraoperative time required make the da Vinci system an impractical tool for many routine procedures. Its true advantage lies in suture-intensive procedures and in surgeries that require meticulous dissection close to major structures. In gynecology, the laparoscopic procedures most likely to benefit from the three-dimensional view and articulating instruments are sacral colpopexy, myomectomy (FIGURE), radical hysterectomy, and lymph node dissection.

Although it is interesting and enjoyable to use robotic technology for routine laparoscopic procedures, I believe the cost is prohibitive—several million dollars for each robot. If the financial barriers are removed, however, this system will be a welcome addition to the toolset for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Until then, we need to make intelligent use of this powerful tool.

FIGURE Robotic myomectomy

A: Using the da Vinci robot, the surgeon incises the myometrium down to the fibroid.

B: After grasping the fibroid, the surgeon dissects it away from the surrounding myometrium.

C: As the fibroid is freed, another small tumor becomes apparent at the bottom right, and is also removed.

D: The myometrium is sutured in layers after removal of the fibroids. Photos courtesy of Paul Indman, MD.Just as many of us were able to perform laparoscopic surgery without a three-chip camera and high-tech energy system for hemostasis until the cost of those technologies could be recouped in reduced operating room time and fewer conversions to laparotomy, so will today’s surgeons have to continue performing laparoscopic adnexal surgery, routine hysterectomy, and treatment of ectopic pregnancy the “old-fashioned” way. For complex procedures, however, the da Vinci system is proving to be a major advance in endoscopic surgery.

Look for other, perhaps less expensive, technologies coming down the road that will, at the very least, permit three-dimensional visualization without the need for robotics. In addition, as I discuss in the next section, miniaturization of robotics is on the horizon. Only our imagination limits our thinking about how robotic technology may be used in the not-too-distant future.

ROBOTICS IN GYNECOLOGY

Selected studies

- Bocca S, Stadtmauer L, Oehninger S. Uncomplicated fullterm pregnancy after da Vinci-assisted laparoscopic myomectomy. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;14:246–249.

- Elliott DS, Chow GK, Gettman M. Current status of robotics in female urology and gynecology. World J Urol. 2006;24:188–192.

- Fiorentino RP, Zepeda MA, Goldstein BH, John CR, Rettenmaier MA. Pilot study assessing robotic laparoscopic hysterectomy and patient outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13:60–63.

- Magrina JF. Robotic surgery in gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2007;28:77–82.

NOTES takes “minimally invasive” to a new level

Imagine performing surgery for ectopic pregnancy or endometriosis in your office, without anesthesia. Think this is impossible? Think again!

A newer, perhaps better, and definitely less invasive version of endoscopic surgery is on the horizon—natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery, or NOTES. In May, a surgeon in Portland, Oregon, performed a cholecystectomy by dropping an endoscope through the patient’s mouth into the stomach, drilling an opening in the gastric wall, and placing small instruments through that opening to perform the surgery. The specimen was then pulled through the small opening in the stomach and retrieved through the patient’s mouth! The stomach was closed with an endoscopic stapling device.

NOTES appears to be the next true advance in minimally invasive surgery. This should come as no surprise to gynecologists. We are the champions of transcervical and transvaginal surgery. General surgeons and gastroenterologists are recognizing what we have long known—that operating through these natural orifices is less uncomfortable for the patient and provides faster, less complicated recovery. They are also recognizing the challenges involved in such an approach.

A new generation of instruments is in the works

Clearly, operating through the vagina, cervix, or stomach necessitates excellent visualization and instruments flexible enough to navigate through tiny openings but strong enough to transect and retrieve tissue. Many of our industry partners are working diligently to create and perfect new instrumentation for NOTES procedures, and research is under way at many centers in this country and overseas into transgastric and transrectal procedures.

Consider what we might be able to achieve with this technology! By eliminating the need for transabdominal access, we can vastly reduce the risk of intestinal and major vessel injury and eliminate the risk of hernia. We can also markedly reduce the discomfort associated with abdominal incisions.

How might this technology be applied in gynecology? I anticipate that ovarian pathology, endometriosis, and ectopic pregnancy will be managed transvaginally or via a small opening in the uterus. Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy—in which warm saline is used as the distention medium instead of carbon dioxide, and access to the pelvis is achieved through a small culpotomy—has been around for many years but is limited by the rigid instrumentation and restricted visualization now available. With flexible instruments that can “see” around corners yet provide a wide visual field, microrobots that can be placed through a tiny opening and then deployed to accomplish the surgical task, and systems to achieve hemostasis, NOTES may be the next revolution in gynecologic surgery.

Still in a very early stage of development, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has generated considerable enthusiasm among physicians leading research and development efforts. Hoping to steer these efforts in a responsible direction—and avoid the problems encountered during the early days of laparoscopic surgery, when many inexperienced practitioners began adopting the technique prematurely—a working group from the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons was formed in 2005, calling itself the Natural Orifice Surgery Consortium for Assessment and Research (NOSCAR). So far, this group has convened two international conferences and penned two white papers, noting that “the overwhelming sense [at the first international conference]…was that NOTES will develop into a mainstream clinical capability in the near future.”1

Some of the needs NOSCAR has identified are:

- determining the optimal technique and site to achieve access to the peritoneal cavity

- developing a gastric closure method that is 100% reliable

- reducing the risk of intraperitoneal contamination and infection, given the transgastric route that has dominated NOTES so far

- developing the ability to suture

- maintaining spatial orientation during surgery, as well as a multitasking platform that would allow manipulation of tissue, clear visualization, and safe access

- preventing intraperitoneal complications such as bleeding and bowel perforation

- exploring the physiology of pneumoperitoneum in the setting of NOTES

- establishing guidelines for training physicians and reporting both positive and negative outcomes.

In the meantime, NOSCAR recommends that all NOTES procedures in humans be approved by the Institutional Review Board and reported to a registry.

So far, the technology has been used to perform appendectomy and cholecystectomy in humans. Research grants totaling $1.5 million have been pledged by industry.

Reference

1. NOSCAR Working Group. NOTES: gathering momentum. White Paper. May 2006. Available at: http://www.noscar.org/documents/NOTES_White_Paper_May06.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2007.

NATURAL ORIFICE TRANSLUMINAL ENDOSCOPIC SURGERY (NOTES)

Selected studies

To date, 19 abstracts on PubMed discuss the impressive opportunities NOTES will provide. Here is a sample:

- de la Fuente SG, Demaria EJ, Reynolds JD, Portenier DD, Pryor AD. New developments in surgery: natural orifi ce transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). Arch Surg. 2007;142:295–297.

- Fong DG, Pai RD, Thompson CC. Transcolonic endoscopic abdominal exploration: a NOTES survival study in a porcine model. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:312–318.

- Malik A, Mellinger JD, Hazey JW, Dunkin BJ, MacFadyen BV. Endoluminal and transluminal surgery: current status and future possibilities. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1179–1192.